Exactly what happened in the New Forest in southern England on August 2, 1100, remains a mystery, despite the fact that it was broad daylight and there were several eyewitnesses.

![]()

On that morning King William II, nicknamed Rufus for his red hair, red face, and violent temper, ate an early breakfast and set off for the forest, equipped with bows and arrows for a day’s hunting. His close friend Walter Tirel went with him.

Once inside the forest, the royal hunting party spread out in search of prey. Tirel remained with the king and soon the beaters accompanying the hunt drove a herd of stags toward the pair. King William shot at them but missed. According to a witness named Knighton, the king shouted to Tirel: ‘Draw, draw your bow for the devil’s sake or it will be the worse for you!’ It has long been accepted that Tirel did as he was told, but his arrow ricocheted off a tree, missing the stag and striking the king in the chest.

The English chronicler and historian William of Malmesbury, writing a few years later, described what happened next.

An account of King William II’s death from ‘A Chronicle of England’, published between 1300 and 1325. William sits on a bench, an arrow in his chest, but still, curiously enough, very much alive.

‘On receiving the wound, the king uttered not a word; but breaking off the shaft of the weapon where it projected from his body, fell upon the wound, by which he accelerated his death.’

Horrified, Tirel rushed to the king, but he was dead. Now Tirel’s only concern was to escape. He leapt onto his horse and spurred it on through the dense forest, galloping furiously without stopping until he reached the English Channel and crossed to France. From there, Tirel vehemently denied killing the king and continued to deny it for the rest of his life.

When news of the king’s death spread, many people in Europe claimed they had experienced premonitions of the event. In Belgium, Abbot Hugh of Cluny revealed he had received a warning on the night of August 1 that the king of England would die the next day. A monk told that on August 2, while his eyes were closed during prayer, he had had a vision of a man holding a piece of paper bearing the message ‘King William is dead’. When the monk opened his eyes, the vision disappeared.

The circumstances of the king’s death remained shrouded in secrecy. Tirel, the prime suspect, was never punished in any way, and most people were inclined to believe his denials. Yet no further investigations into the death took place, nor was any evidence ever submitted. So the death of King William II went down in history as a tragic accident.

The story quickly spread that the king’s death was really a murder that had been disguised as an accident. The disrespectful way in which the king’s body was handled after the fatal hunt seems to point to a murder plot. A lowly charcoal burner named Purkiss was ordered to remove the corpse. Purkiss placed the king on a wooden cart and covered him with an old work cloth. Then he trundled the cart to Winchester Cathedral where William was hastily buried by the monks. This was certainly no funeral fit for a king.

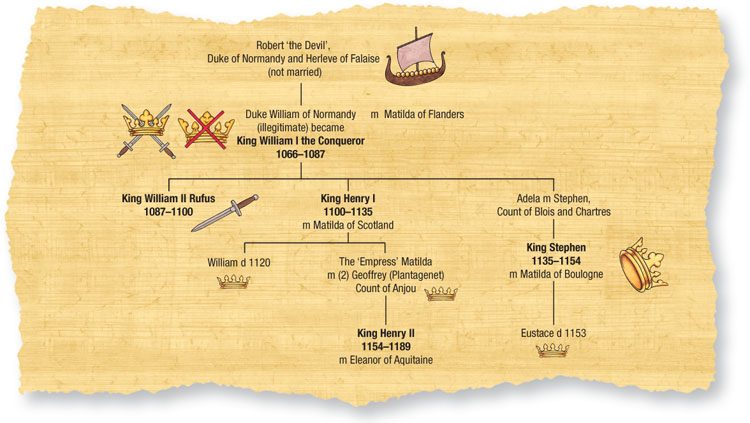

While Tirel was generally presumed innocent, there were several suspects who might indeed have wanted King William dead. The king had never married, and the heirs to the throne were his two brothers: Duke Robert of Normandy, known as Curthose for his short legs, and Prince Henry, known as Beauclerc because he could read and write. Of the two, Henry was the more likely culprit. He had been one of the hunting party and had probably witnessed the king’s death.

As he had been present at the grisly scene, Henry had had the opportunity to act quickly and grab what he most wanted – the throne of England – before Robert, or anyone else, could stop him. He wasted no time mourning his dead brother. Instead, he went straight to Winchester, where he seized the royal treasure, then raced the 60 miles to London and had himself crowned king. It was all over within three days. By August 5, Henry was England’s new sovereign.

Resentful and greedy, Henry had plenty of reasons for having wanted the king dead. When his father, King William I the Conqueror, had died in 1087, Henry had been overlooked and received neither titles nor land. Robert Curthose, on the other hand, was awarded the family duchy of Normandy, in France, and William was placed on the throne of England. All Henry received was £5,000 in silver. Although this was a huge amount of money in the 11th century, it was not nearly enough for a cunning, hard-nosed prince who felt he had been wronged.

Archers, seen here in a reenactment, were the ‘artillery’ of medieval armies. They could fire a barrage which filled the air with a mass of deadly barbs that could fell knights in chainmail – and kill their horses, too.

Robert Curthose was also suspected of wanting the king dead, but it is unlikely that he was involved in the affair. Robert dearly wished to rule England and had been deeply disappointed when his father chose William to succeed him on the English throne. After all, Robert was the elder brother. Twice Robert had tried to seize the kingdom – at the start of King William II’s reign in 1087, and again in 1088 – and twice he had failed.

But William the Conqueror had had good reason for passing Robert over. William had won his crown at the battle of Hastings in 1066, and from then on ruled England by force. He considered Robert weak and easily led. It would have been far too easy for his stronger-willed barons to get the better of him – and that was the last thing William the Conqueror had in mind. The Conqueror wanted a brute like himself to succeed him. That brute was not Robert. It was William.

Ultimately the wily Henry I found it easy to outwit Robert. At the time of William II’s death in the New Forest, Robert had been halfway across the world in the Holy Land, fighting in the crusades. He returned to find his younger brother well and truly in the saddle. Besides claiming the throne, Henry had married Matilda, daughter of King Malcolm III of Scotland, who would soon be pregnant with their first child, the heir to Henry’s throne.

There was no place for Robert at court, and eventually Henry imprisoned him for life until his death in 1134 at the age of 81. Robert never tried to escape, and spent his time learning Welsh and writing poetry.

Other than the Norman royal family there were many ordinary people who would have been glad to see King William II dead. They had good reason. The Norman conquest of England after 1066 had been a savage business. Anyone who resisted Norman rule was cruelly punished. In the rebellious north of England, for instance, Normans burned crops and destroyed hundreds of villages. They slaughtered cattle and sheep, and killed inhabitants by the thousands. Only when the whole area was laid waste were the Normans satisfied.

Hand-to-hand fighting, as seen in this reenactment, was a bloody and barbarous business. Although Norman soldiers wore the chainmail, helmets and kite-shaped shields shown here, they were not immune to the blows of swords and axes.

Normans were just as brutal about the rights they claimed to English forests. Throughout history local peasants had relied on the forests to gather wood for their fires and kill animals for food. Now, anyone who entered the forests faced appalling punishments.

Poachers who shot deer had both hands cut off; even if they merely disturbed the deer they were blinded. And intruders who played music to draw the deer out into the open suffered the same fate. This, though, did not stop the peasants, who continued to enter the forest illegally. So it is possible that the arrow that killed King William II in 1100 was fired by a trespasser hidden among the trees.

The list of King William’s enemies did not end there. The English Church hated him, too. Churchmen wrote the chronicles and histories of the time, and took every opportunity to give William a bad ‘press’. This was the entry for the year 1100 in the most famous of all the medieval histories – the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

This nineteenth-century engraving of King William II Rufus bears a close resemblance to the picture of King Stephen on page 19. Neither picture was a contemporary portrait and no one really knows what either of these kings looked like.

‘He was very harsh and fierce with his men, his land and all his neighbours and very much feared. He was ever agreeable to evil men’s advice, and through his own greed, he was ever vexing this nation with force and with unjust taxes. Therefore in his days all justice declined … he was to nearly all his people hateful, and abominable to God.’

William was not the only royal in his family to suffer. People believed that King Henry I and the entire Norman dynasty were also cursed by God. This seemed to be confirmed when Henry suffered the worst disaster that could befall a medieval monarch.

In medieval times, a king was required to be a warrior. This was why he needed male heirs to succeed him. Henry had sired around 25 children by eight or more mistresses. But they were illegitimate and therefore could not inherit the English throne.

So it was a terrible blow for Henry when his only legitimate son, Prince William, drowned in the English Channel on November 25, 1120. Henry’s courtiers did not dare tell him for two days. When they did, he fainted from shock.

That left Henry’s daughter Matilda as his only legitimate heir. This was a great problem for the king. The 12th century was dominated by men and war, and women were regarded as unsuitable to reign as queens. Henry’s first wife, Matilda, was dead, so he remarried, hoping to have more sons. But Henry, now 53, was unable to father more children. So the king resolved that his only heir Matilda would, after all, reign.

Although she was only 19, Matilda was very much like her father. She was intelligent, forceful, well-educated and self-confident. She was also highly disagreeable. Henry felt sure that Matilda could continue his policy of strong-arm rule. But the decision was not his alone. Matilda had to be accepted by the country’s powerful barons. The barons of England and Normandy were semi-independent, with their own private armies, fortified castles, and extensive landholdings. These were powerful men who were not afraid to voice their opinions to the king.

Henry realized that the barons were much too pig-headed to welcome the idea of a woman reigning over them, but he was desperate. So he commanded the nobles to swear an oath before God accepting Matilda as his rightful successor. Henry made them swear four times – in 1127, 1128, 1131, and 1133. Although the barons resented being forced to take the oath, they were only too well aware that Henry was not a man to be refused.

The barons, however, were just biding their time. As soon as King Henry died in 1135, they went back on their oaths, but not because Matilda was a woman. The barons knew she was more than a match for them and that they would never be able to get the better of her. They had their eyes on a far more malleable candidate.

King Henry I lost Prince William, his one and only surviving son and heir, when the White Ship sank in the English Channel in 1120. The tragic story was told in this manuscript produced two centuries later, in 1321.

Stephen de Blois, Matilda’s first cousin, was a gentleman. He was kind-hearted, good-natured, and tolerant. In other words, he was a promising soft touch. This did not mean, though, that Stephen lacked cunning. As soon as he heard that his uncle, Henry I, was dead, he left France for England. Within three weeks he had raised enough support for his claim to the throne among barons, government officials, and the Church. He also seized the royal treasure. On December 22, 1135, Stephen had himself crowned king.

The result was civil war, because Stephen was a usurper with no legal right to the throne. Also, Matilda had her supporters among the barons who believed in her legal succession. They soon lined up against Stephen but they had to wait for Matilda. She finally brought her army across the Channel to England from Normandy in 1139.

The civil war was a miserable affair. Neither Stephen nor Matilda was strong enough to win a final victory. So, the war ended as a succession of long sieges of castles and other strongholds. The effects on England were devastating. Towns and villages were pillaged by both sides. Refugees wandered the countryside, seeking shelter in monasteries and nunneries. Trade slumped and the barons took advantage of the anarchy caused by the civil war to raid, rob, and rape. A contemporary chronicler, Henry of Huntingdon, described the scenes of suffering:

In December 1142, Empress Matilda and four of her knights escaped from confinement in Oxford Castle wearing white robes to disguise themselves against the thick snow. King Stephen’s guards were too busy carousing to notice them.

‘There was universal turmoil and desolation. Some, for whom their country had lost its charms, chose rather to make their abode in foreign lands; others drew to the churches for protection, and constructing mean hovels in their precincts, passed their days in fear and trouble.

‘Food being scarce, for there was a dreadful famine throughout England, some of the people disgustingly devoured the flesh of dogs and horses; others appeased their insatiable hunger with the garbage of uncooked herbs and roots…. There were seen famous cities deserted and depopulated by the death of the inhabitants of every age and sex, and fields white for the harvest… but none to gather it, all having been struck down by the famine. Thus the whole aspect of England presented a scene of calamity and sorrow, misery and oppression….

‘These unhappy spectacles, these lamentable tragedies…were common throughout England.… The kingdom, which was once the abode of joy, tranquillity, and peace, was everywhere changed into a seat of war and slaughter, and devastation and woe.’

The obnoxious Matilda cared nothing for the sorry plight of the population. In June 1141, while she was in London preparing for her coronation, she demanded huge sums of money from the citizens. But the civil war had ruined them and they could not pay.

When officials and bishops tried to explain the situation, Matilda cursed and swore at them. Very soon, London had had enough. A raging mob burst in on Matilda’s pre-coronation banquet at Westminster. They drove her out of the city. She never returned.

The civil war dragged on, but Matilda’s chances of success were fading. In 1148, she finally gave up and returned to Normandy. King Stephen, it seemed, had won. But within five years, fate gave a bitter twist to his success. His eldest son and heir Eustace died suddenly in 1153. His wife, Queen Matilda, had died the year before. Losing his wife and son was too much for Stephen. Although he had other sons, he was too heartbroken to groom them for the throne. Instead, in 1153, he made a deal with Matilda and her 20-year-old son, Henry Plantagenet. Henry was named as Stephen’s successor on the condition that he allow Stephen to remain king in England while he lived.

But Henry did not have to wait long. Less than a year later, on October 25, 1154, Stephen, the last of the Norman kings, died. Now, Henry Plantagenet became the first monarch of the new Plantagenet dynasty.

Henry was a lot like his mother – hot-tempered, masterful, and stubborn. He was also like a time bomb waiting to go off. What followed was the most vicious royal family quarrel England had ever seen. And it was a fight to the death.

This strong, determined-looking king, dressed in armour, is King Stephen. The portrait is somewhat flattering: the soft, gentlemanly and sensitive Stephen wasn’t nearly as resolute as the picture makes him appear.

Canterbury Cathedral, the scene of the brutal murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket on December 29, 1170. Henry II was thought to have ordered his knights to kill Becket.