When Henry II became King of England in 1154, he was just 21 years old. But he was neither an ordinary man, nor an ordinary king. Despite his youth, he had a natural air of command. He was greatly admired and also greatly feared.

![]()

Yet 35 years later, Henry was a worn out, sick old man. He died deserted by his family and his barons, and humiliated by his great rival, the king of France. The monk chronicler Gerald of Wales wrote that Henry was ‘without ring, sceptre, crown and nearly everything which is fitting for royal funeral rites.’

How could such a brilliant monarch, one of England’s greatest, come to such a miserable end? It all came down to a single, fatal flaw: Henry’s ferocious temperament. First of all, his fiery nature involved him in the most sensational murder of his time. Later, it made his family and his nobles conspire together to destroy him.

Henry II was not only King of England. He also ruled Normandy, Anjou, Maine, Touraine and Poitou in France. When he married Eleanor, a former queen consort of France, in 1152, he acquired his new wife’s own territory, Aquitaine, the largest duchy in France. Together, these lands made up the Angevin Empire. It stretched from England’s northern border with Scotland down to the Pyrenees mountains in southwest France. No monarch of England ever came to the throne with a more splendid inheritance.

The marriage of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine was a marriage of two dynamic personalities. Sooner or later, a violent clash between them was inevitable. Eleanor was not a traditional royal wife. She was heiress to Aquitaine in her own right, and the former wife of King Louis VII of France. She had tasted power long before she married Henry, who was ten years her junior.

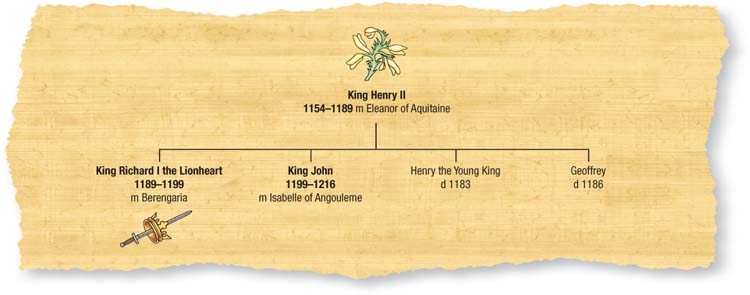

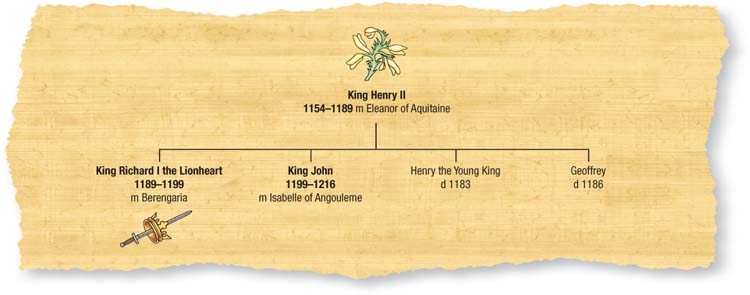

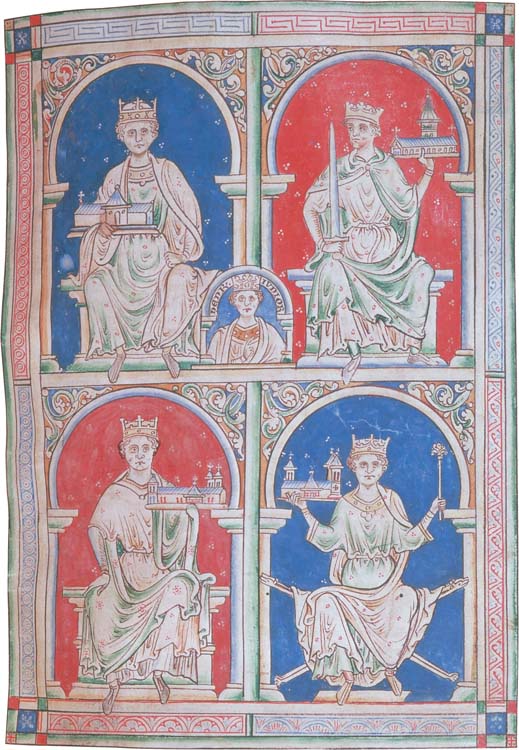

A page from a medieval history of England showing King Henry II, Richard I the Lionheart, King Henry III and King John. Each is holding a representation of a church with which he is associated.

None of these credentials equipped Eleanor to conform to the ‘ideal’ consort of her time – the type of wife who stayed in the background while her husband took the limelight, or was expected to put up with her husband taking mistresses. Sometimes, in such circumstances, the wife and mistress actually became friends.

Eleanor was most decidedly not that sort of woman. She was strong-minded, self-confident and very independent. She objected fiercely to King Henry’s numerous affairs and to his two known illegitimate children. When Rosamund Clifford, considered by some to be the great love of Henry’s life, died suddenly in 1176, it was hinted that Eleanor had had her poisoned. Whatever the truth of the matter, Eleanor seems to have paid back her husband in kind by taking lovers of her own.

Henry II was not a regular medieval king, either. In the 12th century, kings needed to be visibly impressive. Henry was hardly that. He had no interest in the out-ward show and fashionable finery that surrounded other kings. Known as ‘Curtmantle’ or ‘short coat’, he was squat, square and freckle-faced. He often appeared unkempt and even grubby, and thought nothing of appearing at court straight from riding his horse, his clothes and boots covered in mud.

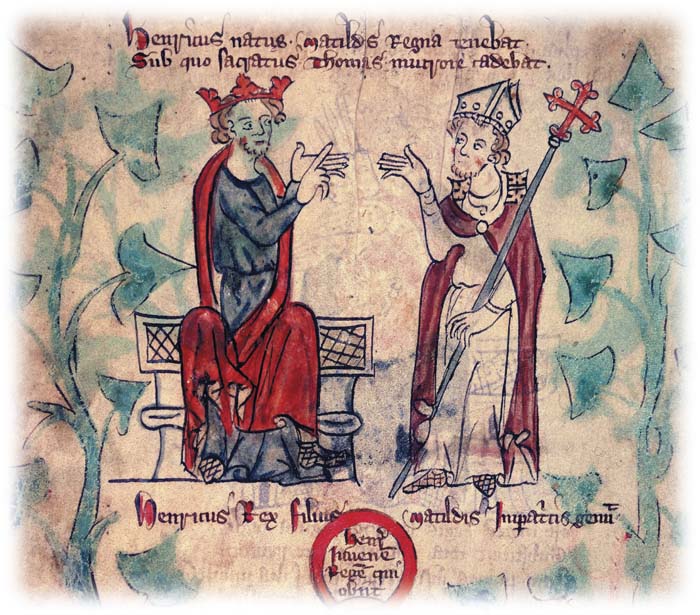

King Henry II and Thomas Becket, once personal friends, argued fiercely about the rights of the Pope over the Church in England. In this medieval manuscript their hand movements represent their diametrically opposed opinions.

In a religious age, Henry cared nothing for religion. He frequently missed church services, and when he did attend, he spent his time sketching and chatting with his courtiers. All the same, beneath this rough and casual exterior, Henry II had a personality that hit people between the eyes. He was stubborn, autocratic and a powerhouse of energy, just like his mother. But also like his mother, his temper was terrifying to witness. When in a rage, Henry went completely over the top: his pale eyes became fiery and bloodshot and he would literally tear his clothes apart, fall to the floor and chew the carpet. Luckily for him, in medieval times, ‘carpets’ were made of loose straw.

Anyone who crossed King Henry II was taking a huge risk. The one man who did so, not once but many times, set the scene for an epic tragedy. Henry appointed Thomas Becket as Chancellor of England at the start of his reign in 1154. Although Becket was 15 years older than Henry, the two men were close friends. They went hunting, gaming and hawking together. Henry gave Becket so many estates and royal grants that Becket became a very wealthy man.

Unlike the king, Becket had a taste for the high life. When Henry sent him on an embassy to Paris in 1158, Becket took with him 250 servants, 8 wagons full of provisions and expensive plates, and a wardrobe of 24 different outfits. In England, Becket kept a personal household of some 700 knights and employed 52 clerks to manage his estates. Devoted to the finest foods, he once ate a dish of eels that cost 100 shillings – at the time a phenomenal price for a meal.

Henry came to trust Becket absolutely. In 1162, Becket became the most important churchman in England when he was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury. But this was more than just the latest in a long line of royal gifts. Ever since the time of William the Conqueror, the kings of England had tried to diminish the power of the Pope over their realm. Making Becket Archbishop of Canterbury was Henry’s way of putting in place a man who would fend off the Pope’s demands. But if this was what Henry believed Becket would do for him, he was completely wrong.

Instead, a complete change came over Becket. He at once resigned as chancellor. He abandoned the good life and all its pleasures, giving away his expensive wardrobe, his fine plates and exquisite furniture. Instead, he devoted himself to study, prayer and acts of charity.

The fact that Henry’s luxury-loving friend had become an ascetic was startling enough. But Becket’s conversion went deeper than outward show. Instead of backing up Henry in dealings with the Pope, he obstructed the king at every turn.

The crunch came when the king demanded that clerks found guilty of crimes in the independent church courts should be handed over to the ordinary, secular courts for punishment. Becket turned this down flat. His relations with Henry, already strained, turned from friendship to black hatred. Henry hit out at Becket by fabricating various criminal charges against him. These included embezzling public funds while serving as chancellor.

When Becket appeared in court, dramatically carrying a large cross, he claimed that, as a churchman, the secular judges had no right to try him. He also appealed directly to the Pope for assistance. Even for Becket, this was going too far. In 1164, realizing his life was in danger he fled to Sens in France.

An engraving of a 12th century crown, which was meant to fit across the wearer’s brow. It might have been worn in battle over the king’s head armour in order to identify him to his soldiers – and his enemies!

Becket’s exile lasted six years. During that time, the king of France and the Pope managed to patch things up between the former friends-turned implacable enemies. This allowed Becket to return to England on December 1, 1170. But deep down his quarrel with the king was not resolved. Once home, Becket proved even more recklessly defiant than before.

Bloodthirsty, headstrong and then remorseful in equal measure, Henry II was a far more hot-tempered and hasty character than this nineteenth-century portrait suggests.

On June 14, 1170, Henry’s eldest surviving son, eight-year-old Prince Henry, had been crowned by the Archbishop of York and became known as the Young King. The crowning of an heir in his father’s lifetime was a failsafe device: it was meant to deter powerful rivals and would-be usurpers. What King Henry had forgotten, or more likely ignored, was the fact that archbishops of Canterbury had a monopoly when it came to crowning English monarchs. As archbishop – even a disgraced archbishop – Becket’s rights had been usurped. He was not prepared to let the insult pass. Instead, he excommunicated the Archbishop of York and the six bishops involved in the Young King’s coronation.

Henry was in Normandy that Christmas, and when the news reached him he flew into one of his terrifying rages, shouting:

‘What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and promoted in my household who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk? Will no one rid me of this meddlesome priest?’

Four of Henry’s knights, Hugh de Moreville, William de Tracey, Reginald FitzUrse and Richard le Breton, took Henry at his word. They crossed to England, arrived at Canterbury whereupon they stormed into the cathedral, fully armed, and slaughtered Thomas Becket. Far from being rewarded for their deed, the four knights were disgraced. They were forced to do penance by fasting. Then they were banished to the Holy Land. But the greatest display of remorse had to come from the king. Soon after the murder, Henry went to Ireland and laid low for a year or more. But the Angevin Empire could not, of course, be properly ruled by a fugitive, so eventually King Henry had to return to England and face the music.

Canterbury Cathedral became a place of pilgrimage after the murder of Thomas Becket. Becket’s shrine was visited by thousands of pilgrims, until it was destroyed by King Henry VIII in the 16th century as an unwelcome reminder of how a subject had defied a king.

King Henry II was made to suffer for the murder of Thomas Becket. Here he is pictured doing penance at Becket’s tomb in Canterbury, a public demonstration of remorse demanded of him by the Pope.

His punishments were grave, but they were not too damaging, except perhaps to the royal ego. Henry was not excommunicated, though he was banned from entering a church. This would hardly have troubled Henry, who was not particularly religious anyway. In addition, his lands in France were laid under interdict: this meant the protection of the Church no longer applied there. So any rival could invade them. And if that happened, Henry could not seek aid from the Pope. But there was more to come.

On July 12, 1174, King Henry walked barefoot through the streets of Canterbury dressed in sackcloth, the traditional garb of humility. He prayed at the cathedral and was afterwards scourged by 80 monks, who beat him with branches. Sore, bleeding and half-naked, the king spent the following night in the freezing crypt where Thomas Becket was buried. Only after this was Henry given a pardon for the sin he had committed.

Unfortunately, King Henry did not learn very much from the Becket affair. He certainly made no attempt to tame his temper or to think before speaking. Far from it. Three years after Becket’s murder, his fiery nature led him into another, much more damaging, quarrel. This time, it led to disaster.

In 1169, at Montmirail, some 40 miles east of Paris, King Henry shared out his vast empire between three of his four surviving sons. Prince Henry, heir to the throne and now aged 14, would have England and Normandy. Richard, 12, the future King Richard the Lionheart, received his mother’s Duchy of Aquitaine. The fourth surviving son, Geoffrey, aged 11, was to have Brittany in France. The youngest, John, received no lands, for he was only two years old when the arrangements were made. But this was not due to any lack of fatherly affection.

John, who was given the nickname of ‘Lackland’, was Henry’s best-loved child. The king made several efforts to provide for him. These efforts included marriage to a wealthy French heiress, but it never came about. In 1177, when John was aged 10, Henry made him Lord of Ireland. Eight years later, John visited Ireland. But he spent his time frittering away his father’s money on luxury living, and annoyed the Irish by poking fun at them.

As for Henry’s other sons, they fully anticipated ruling the lands they had been given. They also expected to receive the revenues their lands produced. But King Henry had never intended his sons to have any real power in his lifetime. They were simply figureheads. All power and revenues remained in their father’s hands.

But Henry was not going to be able to get away with handing out empty promises. In 1173, his sons’ resentment boiled over into open rebellion. Queen Eleanor, who had grudges of her own against the king, was their chief ally. Henry’s sons also found many malcontents to join them, including barons in both England and Normandy who chafed under King Henry’s control. But by far their most important supporter was King Louis VII of France, their mother’s former husband.

Louis coveted Henry’s Angevin lands and was only too pleased to help his rival’s sons destabilize their father’s power. Not this time, however. In 1173, King Henry had sufficient military punch to put down the family rebellion and it came to nothing.

Even before the actual rebellion, Queen Eleanor had realized what a dangerous game she was playing. She tried to slip away across the English Channel to Chinon, in Anjou, disguised as a man. But she was recognized and brought back to England. Henry placed her under house arrest at Winchester, where she remained for the next 16 years.

The seal of King Henry II, showing him seated on his throne, sword in one hand and in the other the orb that was an indication of his royal authority. Royal seals on documents and charters showed they had royal sanction and were therefore legal.

Once the rebellion was over, King Henry was arguably more generous towards his sons than they deserved: he forgave them and presented the Young King and Prince Richard with castles and revenues. This gesture, he hoped, would prevent them from rebelling again.

But the family disputes were not over. King Louis of France died in 1180 and was succeeded by his much more capable and far more dangerous son, King Philip II Augustus. Together with his father’s throne, Philip inherited his father’s plans to poach the Angevin lands. The Young King and Geoffrey were ready-made stooges for Philip’s wiles, but the French king’s plans were stymied when both of them died prematurely. The Young King died of dysentery and fever in 1183. Geoffrey, who had a passion for tournaments, was killed in 1186 while fighting in the lists.

Only two of Henry’s four legitimate sons were left. John remained faithful to his father, but Richard was nursing a new grudge: the king planned to give John certain castles in France which Richard claimed as his own. Even worse, King Henry refused to recognize Richard as heir to the English throne, even though, with the death of the Young King, he had become the eldest surviving son.

Henry II was heartbroken when he learned that his son John had betrayed him by joining his brother Richard in open rebellion. This picture shows the moment when the king, hand clutched to his heart, received the news.

This was how Philip got a second chance in his bid to destroy the Plantagenets and their Angevin Empire. No one knows if Richard knew about Philip’s secret agenda. But he made no bones about joining the French king in a last all-out assault on his father in 1189.

King Henry had known all along that this was going to happen. Before the death of the Young King in 1183, he had commissioned a painting and ordered it to be displayed in the royal chamber of Winchester Palace. The painting showed four eaglets attacking a parent bird. The fourth eaglet was poised to peck out the parent’s eyes.

The four eaglets’, the king explained ‘are my four sons who cease not to persecute me even unto death. The youngest of them, whom I now embrace with so much affection, will sometime in the end insult me more grievously and more dangerously than any of the others.’

The King’s prediction came true when Prince John deserted his father and joined forces with Richard: the castles his father planned to give him were not grand enough for John’s ambitions. The news broke Henry’s heart. After that, the end came quickly.

A silver penny minted in the reign of King Henry II. The king’s portrait, together with his sceptre, the symbol of his power, is on the obverse. The lettering on the reverse, shows that the coin was minted in London.

Richard and King Philip stormed across the territories of the Angevin Empire in northern France, capturing each of the king’s strongholds, one after the other. At the same time, almost all the barons of Maine, Touraine and Anjou deserted Henry. Driven out of Le Mans, where he had been born, Henry fled to Chinon in Anjou and took refuge in his castle. His enemies pursued him even there. On July 4, 1189, they made humiliating demands on Henry. There was no way he could resist them.

Guillaume le Breton, King Philip’s chaplain and biographer wrote:

‘He resigned himself wholly to the counsel and will of Philip, King of France, in such a way that whatever the King of France should provide or adjudge, the King of England would carry out in every way and without contradiction.’

Sick at heart and already ill with a fever, Henry died five days later. As he lay dying, he cursed his sons for their treachery. Only Geoffrey, his illegitimate son by Rosamund Clifford, was there at his bedside. This was how the chronicler Gerald of Wales described the last painful days of King Henry II:

‘For as branches lopped from the stem of a tree cannot reunite,’ he wrote ‘so the tree stripped of its boughs, a treasonable outrage, is shorn both of its dignity and gracefulness.’

Although he shamefully neglected his kingdom of England, Richard the Lionheart has long been admired as a great and valiant warrior monarch. This statue stands in Old Palace Yard, close by the Houses of Parliament in London.