When he learned of his father’s death, the first thing the new king, Richard I, did was to go and pay his last respects to the parent he had betrayed. He didn’t waste much time on it. Some said Richard knelt beside his father’s body only for as long as it took to recite the Lord’s Prayer.

![]()

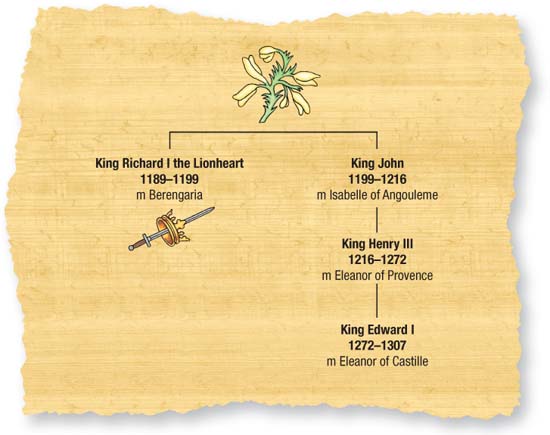

Next, Richard freed his mother, Queen Eleanor, from imprisonment at Winchester. Richard’s coronation took place in September 1189. After that, he returned to Aquitaine. Leaving England set the pattern for Richard’s reign.

Richard was already a celebrated warrior, so much so that he was nicknamed the Lionheart. He certainly stands as the ultimate fighting king of medieval times. But he had no interest in fighting to defend England. Apart from crusades, Richard’s main aim in life was defending his beloved Duchy of Aquitaine against the French king, Philip II.

Philip was not Richard’s only dangerous enemy. Richard’s younger brother, John, aimed to seize England during several of Richard’s frequent absences. The chronicler Richard of Devizes once described John as ‘a flighty, habitual traitor’. John had no reservations about betraying his brother, just as he had betrayed his father.

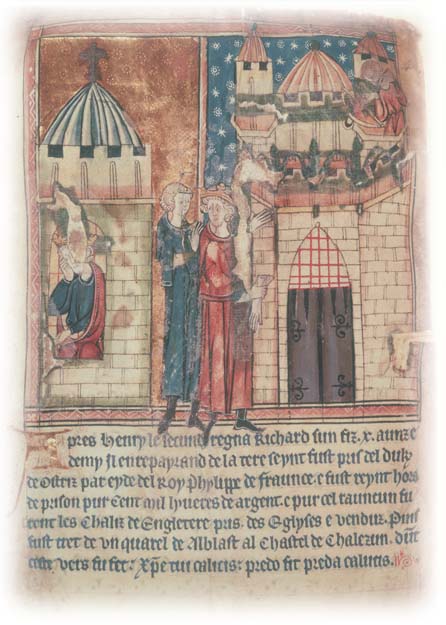

This picture, painted between 1475 and 1500, shows the coronation of King Richard I, which took place in London on September 30, 1189. Barons, bishops and monks took part in the coronation procession.

Even so, Richard was fond of John. He arranged a marriage for him with a wealthy heiress, Isabel of Gloucester, and gave him huge estates in England. This, though, was not good enough for John, who had his heart set on becoming regent of England when Richard left on a crusade. Instead, Richard chose his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, to look after his kingdom. John also expected to be named as Richard’s heir. But that prize went instead to four-year-old Prince Arthur of Brittany, son of their late brother Geoffrey. As time would tell, John would deal with Prince Arthur in his own ruthless way.

Embarking on crusades to fight Muslims in the Holy Land was phenomenally expensive. To raise much-needed funds, King Richard virtually put England up for sale. He sold earldoms, lordships, sheriffdoms, castles, lands, estates, entire towns and anything else convertible into ready cash. He even planned to sell the capital, London. But, so he complained, he could not find anyone rich enough to buy it.

At last, in July of 1190, Richard set out for the Holy Land with a fleet of more than 100 ships and 8,000 men, intending to return within three years. But that was not to be.

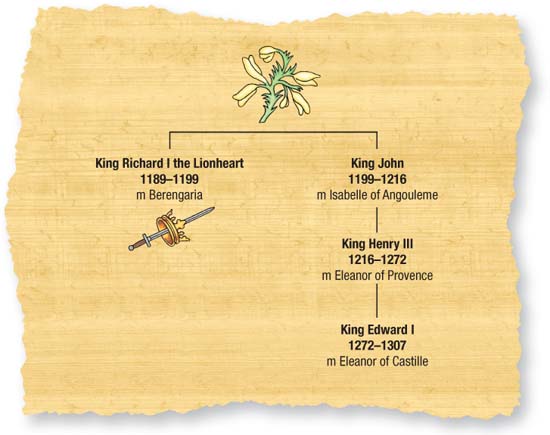

In military terms, the Third Crusade was a success. Richard gave the Muslims a thrashing and was hailed as an even greater hero than before. But while in the Holy Land, Richard made a crucial error. He insulted a fellow crusader, Duke Leopold of Austria. Leopold swore vengeance and spotted his chance when Richard was on his way home by sea in 1192. Richard’s ship sank near Venice. From there, Richard was forced to complete his journey overland. In Vienna, Austria, Duke Leopold was waiting for him.

Many stories went around about how Richard slipped up, enabling Leopold to capture him. One had it that Richard tried to pass himself off as a kitchen hand, but forgot to remove an expensive ring that no kitchen hand could possibly have owned.

This picture, from the Luttrell Psalter (1300–1340) shows King Richard and Saladin jousting at a tournament. Saladin is portrayed with a fearsome blue face. The picture is fanciful: in real life, Richard and Saladin never met at a tournament.

Once Leopold got his hands on Richard, he went for a quick profit. He ‘sold’ Richard to Emperor Henry VI of Germany. With this valuable ‘property’ in his possession, the emperor demanded a huge ransom. To make the most out of his rare acquisition, Henry put Richard up for auction. One of the main bidders was Richard himself. The others were King Philip and the faithless Prince John: John had allied himself to the French king as part of his latest scheme – to take Richard’s lands in France.

This was an auction Richard had to win. If he had lost, King Philip would have had his wicked way with the Angevin lands in France. And Prince John would get his greedy hands on England. Fortunately, Richard was able to outbid his rivals. The ransom was set at 150,000 marks of silver.

Once again, England was milked dry to raise this immense sum of money. Every possible money-raising device was used. Church gold and silver plate were seized and sold. A whole year’s wool crop was taken from ranches run by two Cistercian monasteries, and a hefty 25 percent tax was levied on all incomes.

Richard was finally freed after 16 months, on February 4,1194. He arrived in England about six weeks later.

Prince John had been informed that Richard was on his way. King Philip warned him: ‘Look to yourself, the devil is loosed’. As soon as he heard Richard was coming home, John fled to Philip’s court for protection. He was terrified of what would happen when his brother found him. Luckily for him, Richard did not punish John too severely. He took away John’s lands for a time, but only to teach him a lesson, and they were soon restored.

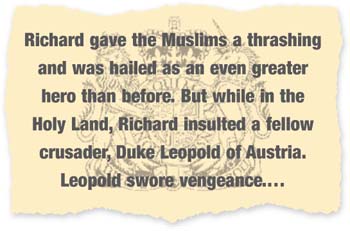

A picture illustrating Richard’s imprisonment in Austria, painted in 1200, the year after his death. Richard appears twice, in the middle holding a glove, and looking thoroughly fed up at a window, on the left.

‘Think no more of it, John’, Richard told him, ‘You are only a child who has had evil counsel.’ Yet John was no child – he was 27 years old at the time.

Although he forgave and indulged him, Richard did not trust his younger brother. He gave him no powers in England when Richard once more left for France on May 12, 1194. Richard never returned. King Philip was still preying on the Angevin lands, and Richard spent the last five years of his life fighting to keep him at bay. In 1199, he was badly wounded during the siege of Chalus Castle in Limousin. The wound became septic and killed him.

When news of his brother’s death reached him, Prince John was in Brittany. He acted fast and returned to England at once. John spent the next few weeks gathering support from the barons and the clergy. That done, he had himself crowned king at Westminster Abbey on May 27, 1199. Next, John prepared to provide his throne with heirs. He divorced his childless wife, Isabella of Gloucester, and married another Isabella, 12-year-old heiress to Angoulême in France.

John’s second marriage was controversial from the start. Isabella had already set her heart on another man – Hugh de Lusignan. Hugh loved Isabella in return and the couple were betrothed. But Isabella’s ambitious family had other ideas. They saw great advantage for themselves in having her as queen of England. If that meant Isabella had to give up the love of her life, well, so be it. Isabella dutifully married King John, who was 20 years her senior, at Bordeaux Cathedral on August 24, 1200.

Hugh de Lusignan was furious and complained to King Philip. Philip, of course, was only too pleased to beat the king of England with this particular stick. He demanded that the king explain himself. John, meanwhile, attempted his own solution. He tried to appease Hugh de Lusignan by offering his own illegitimate daughter, Joan. Hugh declined. In 1202, John refused to appear before Philip, as ordered. This gave the French king the excuse he needed to confiscate all John’s lands in France. For the moment, though, Hugh de Lusignan had lost his Isabella.

For John, there still remained the problem of his nephew, Prince Arthur of Brittany. As the son of John’s elder brother, the late Geoffrey, Arthur had a better claim to the English throne. King Philip, always on the lookout for ways to cause trouble for John, supported Arthur’s claim. So did the barons of Anjou, Maine and Touraine. This was powerful opposition, but then John had a stroke of luck.

While in France in the summer of 1202, fighting to regain the lost Angevin lands, he managed to capture more than 250 knights during his siege of Mirabeau Castle in Aquitaine. One of them was Arthur of Brittany.

Arthur was imprisoned at a castle in Falaise belonging to John’s chamberlain, Hubert de Burgh. John supposedly wanted Arthur blinded and castrated, but Hubert de Burgh would not hear of it. De Burgh was not alone in his disdain for the king’s plan. Another great magnate, William de Briouze, fourth Baron Briouze, also refused to countenance so callous a retribution.

King John is shown paying homage to King Philip of France for his French lands. Although he was King of England, John was the vassal of the French monarch, and regular homage reinforced his fealty to his lord.

In this illustration, King Henry III is flanked by two bishops who have just placed a crown on his head. This is possibly meant to illustrate Henry’s coronation, although at the time, he was a young boy, not a grown man.

John was not going to let the baron get away with such treachery. He marked down William de Briouze and his family for future punishment. As for Arthur, he was transferred to one of John’s own castles, at Rouen. Once there, the king could do what he liked with him. Soon afterwards, Prince Arthur disappeared from history.

By his ruthless and cruel treatment of the de Briouze family and others, John had fully alerted his barons to the fact that he was a dangerous tyrant. Even then, John might have saved himself had he proved to be that medieval ideal – a successful warrior king. Instead, he lost the Angevin lands in France to a triumphant King Philip in 1204. The magnificent Angevin Empire was gone forever. With this loss, the barons coined another nickname for John: ‘Softsword’. It was the worst insult the barons could have dreamed up.

John, in turn, became intensely suspicious of anyone with power in the land. He even pursued barons who remained loyal to him, forcing some to become royal debtors by imposing huge sums in return for new titles. His victims, of course, could not refuse. Geoffrey de Mandeville, for example, was obliged to offer 20,000 marks for the earldom of Gloucester: part of the deal was that Geoffrey took John’s former wife, Isabella of Gloucester, off the king’s hands.

The king’s bloodthirsty activities were taking a toll on his supporters. His treatment of the barons eventually became too much for them, and they rebelled. At Runnymede on June 15, 1215, the barons forced John to sign the Magna Carta. This was not a declaration of democratic liberties, as is often thought, but a statement of the barons’ rights and privileges.

However, breaking his word came all too easily for King John. He reneged almost at once. Civil war ensued. Surprisingly enough for ‘Softsword’, John was soon winning. In desperation, some barons turned traitor: they invited Louis Capet, the son of King Philip of France, to bring an army to England. Louis Capet was to remove King John from the throne and take his place.

Louis arrived at Dover, on the south coast of England, on May 14, 1216. Twelve days later he reached London, where his forces captured two important strongholds: the White Tower, at the Tower of London, and Westminster Palace. That done, Louis was hailed as King of England by his army. But in Rome, the Pope had other ideas. Louis had broken rules by attacking a rightful Christian king. As punishment, the Pope excommunicated Louis and placed his lands in France under interdict.

Meanwhile, John was gathering support all over England. If there was one thing the English detested, it was a foreigner attempting to snatch the throne. They would rather be ruled by a home-grown king like John, however unsatisfactory he was.

A charter issued by King John, dated May 9, 1215, carrying the royal seal. The same design was often used for seals in successive reigns. The royal seal validated the document to which it was attached and was therefore a protection against forgery and fraud.

Then, quite suddenly, John died of dysentery on October 18,1216. He was succeeded by his nine-year-old son, who became King Henry III. Now that the barons had a rightful king with no track record of dark deeds and dirty doings, their support for Louis Capet began to fall away.

But England was still in crisis, and Henry III’s coronation was a hasty, hole-in-the-wall affair. The child-king, mother Queen Isabella and the royal family had fled to England’s west country after Louis Capet reached London. This was why the ceremony took place in Gloucester Cathedral on October 28, 1216, ten days after John’s death. It was a coronation without a crown: instead, Henry had to make do with his mother’s torque, a small twisted gold necklace.

The situation in England was still very dangerous. Fortunately, William the Marshal, who was appointed King Henry’s regent, was a splendid fighter. He soon dealt with Louis Capet. The French prince was forced to sign a peace agreement in London on September 12, 1217. By 1219, William the Marshal had the barons under control and order was restored. Only then, when she knew her son was safe on the throne, did Queen Isabella return to France. There, in 1220, she at long last married Hugh de Lusignan. Their long-delayed marriage was a happy one, and the couple had nine children.

Henry’s views on the status of kings were ill-considered and unrealistic. He did not seem to understand that English kings had never been absolute rulers: there was always some assembly – the Anglo-Saxon Witangemot, the barons, ultimately Parliament – which took it as their right to ‘advise’ the monarch. Challenging such a right was something even kings could not get away with. As long as he remained under age, Henry’s views on kingship did not matter too much. But he failed to outgrow them once he took on his full royal role in 1227.

There were serious differences between the interests of the king and those of his barons. Henry loved all things French. His barons had little interest beyond the shores of England. Henry dreamed of regaining the lost Angevin lands and even extending the empire eastward into Germany. The barons could not have cared less.

At court, where the barons believed they should have a major influence, they were vastly outnumbered by the French. Henry took a French wife, Eleanor of Provence, in 1236 and filled his court with her relatives. There was always a warm welcome, too, for the king’s Lusignan half-brothers, the sons of his mother Isabella by her second marriage. But worst of all by far, King Henry ignored his barons and surrounded himself with French advisers.

One was Peter des Roches, who had served King John. Des Roches believed that royal power should be unrestricted and encouraged King Henry to become a despot. Another influential adviser was William of Savoy, Queen Eleanor’s uncle, who became important in the royal council. Even the Archbishop of Canterbury was a Frenchman – Boniface of Savoy, another of the Queen’s uncles.

But then King Henry himself wrecked the whole situation, and gave the barons their chance to get their own back. The king was fond of ambitious, crazy schemes, and in 1254 he ran into big trouble. He had made a deal with the Pope to conquer the Mediterranean island of Sicily: after that, Henry had planned to make his second son, Prince Edmund, king. To fund this plan, the Pope gave permission for King Henry to exact heavy taxes from his subjects. Henry’s barons were furious. They had no interest in the King’s mad plan. They refused to pay. The Church refused, too. The ordinary people were struggling with bad weather, failed harvests and famine, so they could not pay either.

Henry was unable to raise the funds agreed upon. There were rumblings from the Pope, and the king was threatened with excommunication. But with the king in trouble, a far greater threat came from a great council convened by the barons. In 1258, they drew up a long-term plan called the Provisions of Oxford. This was intended to banish French members from Henry’s court.

Under the Provisions, the most important government posts were to go to Englishmen. The royal revenues were to be paid directly into the Exchequer: this was to prevent King Henry from frittering funds away on his French admirers. Among the most important provisions was the setting up of a 15-man baronial council to ‘advise’ the king. It was actually intended to control him.

Henry was caught off guard. The royal treasury was almost empty. His subjects were starving. Their mood was turning ugly. He was left with only one course of action – give in. So Henry duly signed the Provisions of Oxford. This kept the barons happy for a time. But at once, Henry started to look for ways to renege.

Henry had to wait awhile for the chance to go back on his word. It came in 1264, when the barons, always vicious rivals, began to quarrel among themselves. But when Henry renounced the Provisions of Oxford, they set their rivalries aside. War followed, and extreme humiliation for King Henry. At the battle of Lewes in Sussex on May 14, 1264, the king and his son and heir, Prince Edward, were taken prisoner. They fell into the hands of the barons’ charismatic leader, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester.

Ironically, de Montfort was a Frenchman who had inherited an English earldom through his mother in 1230. He was every inch a brutal, macho, self-seeking baron. But he possessed a magnetic personality that overwhelmed lesser men. He was also a brilliant military leader of the Richard the Lionheart class.

Henry had been so impressed with Simon that in 1238 he had been allowed to marry the king’s sister, Princess Eleanor. But Simon was not the sort of man to bow and scrape to his royal brother-in-law. Far from it. Simon had little time for the cowardly king. He once told Henry he should be locked up because of his feeble military abilities. Nor was Simon afraid to exploit his grand position to the fullest. He was impudent enough to use the king’s name without permission to secure loans. He almost ended up in the Tower of London for such acts.

But when Henry reneged on the Provisions of Oxford, it was too much for Simon de Montfort. As far as he was concerned, breaking an oath was more than just blasphemy – it was an insult to God.

Thus Simon treated Henry III with even more contempt after the battle of Lewes. The king was not only Simon’s prisoner, he was Simon’s hostage and puppet. Nor was Simon above intimidating Henry. He forced him to sign certain laws, orders and other documents. In 1265, he also convened a Parliament – something only the king could normally do – and made Henry submit to its demands. No king of England had ever suffered such humiliation, not even King John.

The barons in this 19th-century engraving look respectful as they bow to King Henry, but what they’re really doing is making their demands. This is why Henry, standing with a crown on his head, looks so wary.

King Henry’s son, Prince Edward, was kept prisoner along with his father. Edward, aged 25, was much more gutsy than Henry. He was not afraid of the mighty Simon de Montfort. Edward knew, too, that many barons were chafing under Simon’s rule. They objected fiercely to the way he was feathering his family nest while the king was in his power.

The South Nave Aisle of London’s Westminster Abbey, photographed in 1912. After he regained his throne in 1265, Henry III left political affairs to his son, Prince Edward. Instead, Henry spent the last seven years of his reign working on the restoration of the Abbey.

First, though, Prince Edward had to escape. His opportunity came on May 18, 1265, while he was out riding near Hereford in the west of England. He was watched by guards, including Simon’s son, Henry de Montfort. Another of the guards, Thomas de Clare, seems to have been involved in the plot. Edward was riding side by side with Henry de Montfort when, by a given signal, he edged away. Then he spurred his horse and galloped off. Thomas de Clare followed. Though chased by other guards, they managed to make their escape.

Now that Edward was free, the discontented barons had a leader. A few weeks later, led by Edward, the forces of the king met Simon’s army at Evesham in Worcestershire. Edward organized a hit squad to seek out Simon de Montfort and kill both him and his followers.

After this overwhelming and bloody victory, King Henry was restored to his throne. He immediately revoked all the documents Simon had forced him to sign. But at last he had learned his lesson. In the seven years until his death from a stroke in 1272, Henry concentrated on completing a new Westminster Abbey, leaving the government of England to Prince Edward.

As the Battle of Evesham demonstrated, Edward was not in the least like his father. Forceful and brutal, he was willing to shed blood in buckets to get his own way. But as King Edward I after 1272, he was also the strong, dominant royal leader England had been lacking for more than 80 years. The downside was that Edward I was a hard act to follow. The son who had to follow him in 1307 was not up to the job. Yet another scandalous reign loomed over England. And the new king, Edward II, was going to suffer for it in the most ghastly way his enemies could devise.

On February 28, 1308, Edward II and his wife Isabella were crowned king and queen at Westminster, London, by the Bishop of Winchester.