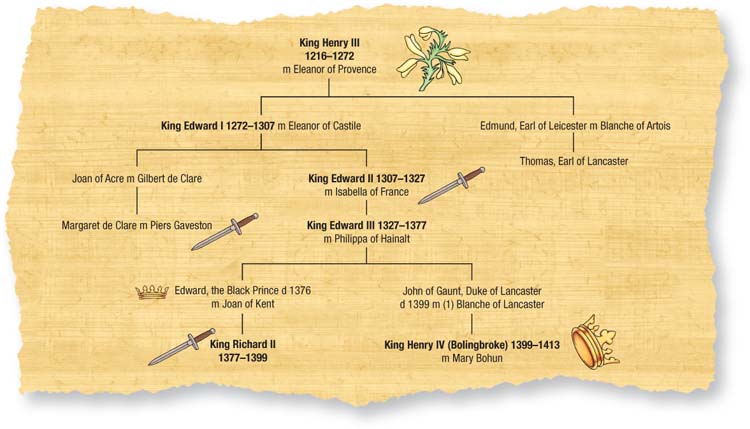

Edward II was undoubtedly a disaster on two legs. Long before he became king in 1307, his courtiers and officials knew all about his curious habits and strange interests.

![]()

Edward enjoyed menial pursuits. He liked nothing better than digging and thatching, very undignified work for an heir to the throne. The barons were thoroughly scandalized. For them, it was bad enough that Edward was no good at proper royal activities – like jousting in tournaments and making war. But a king who enjoyed grubbing around in the earth like a peasant was just too much.

This was not the worst of it. Edward II was a blatant homosexual. Except for his wife, Queen Isabella and her ladies-in-waiting, Edward banned women from his court. He was much more interested in beautiful young men like his beloved ‘Perot’ – Piers Gaveston, a Gascon knight who became his closest companion. No one doubted that Edward and Gaveston were lovers. They had known each other since they were children. Gaveston was good looking and physically attractive. Unlike Edward, he excelled at jousting tournaments. He made a habit of challenging barons to matches and beat them all. What’s more, he insulted them by poking fun and assigning them rude nicknames. They hated him.

While King Edward I was still alive, father and son had violent public quarrels over Gaveston. Twice, the old king threw Gaveston out of England, and forbade him to return. But once his father was dead and he became king, there was no holding back King Edward II. He immediately recalled Gaveston to England and showered him with gifts. He made him Earl of Cornwall and lord of the rich estates that went with the title.

Gaveston married Edward’s niece, Margaret Clare, a rich heiress in her own right. But Margaret’s marriage was no more fulfilling than Isabella’s. Their husbands were besotted with each other and the wives had to take a back seat.

King Edward was warned often enough that he was playing a dangerous game. But he was stubborn, always wanted his own way, and paid no attention. Secure, so he thought, in the love of the king, Gaveston himself became unbearable.

‘He lorded it over (the barons) like a second king, to whom all were subject and none equal’, wrote the monk of Malmesbury. ‘For Piers accounted no one his fellow, save the king alone…. His arrogance was intolerable to the barons and a prime cause of hatred and rancour.’

Edward took every opportunity to show off his lover. The greatest performance of all was at his coronation in 1308, where a major role was bestowed upon Gaveston: he carried the crown and another precious piece of regalia, the sword of Saint Edward. So splendidly dressed was he that it was said he appeared more like the Roman god Mars than a mere mortal.

At the feast that followed, Gaveston sat next to the king in the place Isabella should have occupied. Even more shocking, the king and his lover repeatedly fondled each other at the table while the guests watched, open-mouthed.

Isabella was only 12 years old when she came to England to marry King Edward II. It was a dynastic marriage, meant to ally England with France. But for Isabella, a homosexual husband was not part of the deal. Nor did she expect to see Gaveston wearing rings and jewels that her father had given Edward as wedding presents. So it wasn’t long before the child bride was writing to her father complaining she was ‘the most miserable wife in the world’.

Queen Isabella was too young to do anything about her wretched situation. But the barons had no intention of sitting helplessly on the sidelines. They planned to get rid of Gaveston. Fortunately, the barons had among them the leader they needed to oppose King Edward and bring Gaveston down: Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, Leicester, Derby, Lincoln and Salisbury, and lord of extensive lands in the north of England. Thomas was King Edward’s first cousin. He was vicious, greedy, ambitious and self-serving. And he hated Edward with a passion.

Brute force and threats came naturally to Thomas of Lancaster and his fellow barons. In 1308, they resorted to both. Like his grandfather, Henry III, Edward was at heart a coward. He caved in to the barons’ demands.

Gaveston was again forced to leave England. But he soon returned, and the barons had to turn up the pressure. On September 27, 1311, the barons warned Edward that if he did not get rid of Gaveston the result would be civil war. Once again, Edward caved in. Gaveston left for France, but again he came back, this time within three months, at Christmas, 1311.

Eventually the barons acknowledged that exile was not working. Gaveston would always find some way to sneak back to his lover. And the infatuated king would always welcome him, quite literally, with open arms.

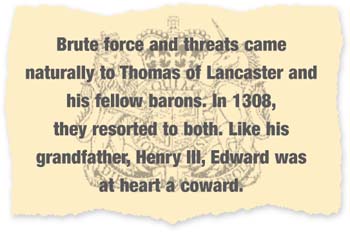

The English barons were sick of the effeminate Piers Gaveston, who was stopping them from exerting influence over King Edward II. Once they made Gaveston their prisoner, he was doomed. He was summarily killed, without trial.

The barons knew what they must do. On June 9, 1312, they had Gaveston kidnapped and imprisoned in Warwick Castle. The castle belonged to Thomas of Lancaster. Ten days later, Gaveston was marched out, barefoot, to nearby Blacklow Hill. There, two of Thomas’s men impaled him on their swords and hacked off his head.

King Edward was distraught. He wept and lamented over his murdered lover. But killing Gaveston was not the barons’ only intention. They were determined to grab top positions in the king’s government. So, in 1311, they forced Edward to agree to a set of ordinances. Edward was forbidden to leave England without the barons’ permission. He must stop appointing ministers and officials. He had to summon Parliament at least once a year. Parliament would control the king’s finances. It was a straitjacket: the purpose was to prevent another Piers Gaveston from monopolizing the king.

Edward chafed and fumed over these restraints. All the same, for nine or ten years, he more or less behaved himself. He had had to. Thomas of Lancaster, now the real ruler of England, was watching everything he did. Then, in about 1320, the king’s love life started to heat up again. He managed to sneak two new close friends into his court – a father and son, both named Hugh Despenser.

It was the Gaveston business all over again. The Despensers snapped up gifts, estates and money. Hugh Despenser the son acquired a rich wife who was one of the heiresses to the earldom of Gloucester. Between them, the Despensers kept the king to themselves. Presumably, both were his new homosexual lovers.

Thomas of Lancaster wanted to ensure Gaveston was dead and ordered one of the Welshmen who had killed him to show him Gaveston’s severed head. After this, a Dominican friar took it to show King Edward.

Just how damaging these men’s power over the king became was revealed by the French chronicler, Jean Froissart:

‘…Hugh Despenser told King Edward that the barons had formed an alliance against him and would remove him from the throne if he was not careful. Swayed by [Despenser’s] subtle arguments, the king had all these barons seized at a Parliament at which they were assembled. Twenty-two of the greatest…were beheaded, immediately and without trial….’

But the barons who survived this slaughter were undaunted. They were still gunning for the Despensers. They went to the king and in July 1321, demanded that father and son be exiled. King Edward was thoroughly cowed. The barons got their way, only to find history repeating itself. Within a few months, Hugh Despenser the son was back in the arms of the king. Hugh Despenser the father also returned to England. Edward welcomed him back with a great gift: he made him Earl of Winchester.

This portrait of Queen Isabella, wife of Edward II, is very deceptive. Here, she looks sweet, good natured and gracious. In real life, Isabella was the vicious mastermind behind the downfall and death of her husband.

When the Despensers were exiled, the barons described them as ‘evil counselors.’ It was a surprisingly mild term for leeches who were taking King Edward for everything they could get. But for Queen Isabella, the Despensers were much more than that: they were symbols of her years of humiliation and neglect.

Isabella also had a personal reason for wanting revenge on the Despensers. In 1324, they had seized her lands in France. They had also taken her four children from her. They planted spies in her household to keep an eye on her. By this time, Isabella was no longer the helpless little girl who had married the king in 1308. Now a mature 28, she had become the so-called She-Wolf of France and she was about to show just how terrible the fury of a woman scorned could be.

Although he had neglected her shamefully, King Edward trusted Isabella’s political abilities. In 1325, he sent her to France to negotiate a dispute between himself and her brother, the French King Charles IV.

While she was in Paris, Isabella met Roger Mortimer, the wealthy and ambitious seventh Baron Wigmore. Mortimer was just the sort of man to appeal to a new, vengeful Isabella – a man’s man, rough, tough, brutal and arrogant. Mortimer became Isabella’s lover and the two openly lived together. And together, they plotted the downfall of King Edward II.

Mortimer and Isabella raised an army and on September 24, 1326, they invaded England. The immediate targets were the Despensers, who were rounded up and duly murdered, brutally. The king, too, was ambushed and taken to Berkeley Castle, near Bristol Channel in southwest England. There, he was forced to abdicate on January 24, 1327. The next day, his son, 14-year-old Prince Edward, was proclaimed King Edward III. Later that year, Edward II also met an almost inconceivably cruel end.

Isabella and Roger Mortimer, who was made the Earl of March in 1328, were now the rulers of England. Mortimer’s main concern was to enrich himself and his family, and he did not care how he did it. He seized lordships, castles and estates and any other treasure he could lay his hands on.

Isabella was no better. She plundered the royal treasury. She made huge grants to herself and her lover. She used Parliament to rubber-stamp any laws and orders she wanted. The situation could not continue. Isabella would have to go – and Mortimer with her.

At first, though, the underage King Edward III had no authority to act against the regal pair. Not until he turned 16, in 1330, was he able to take on the full powers of king. One of his first acts was to destroy Roger Mortimer.

In October 1330, Mortimer and Isabella were staying at Nottingham Castle. They knew they were in danger and had ordered the gates locked. Guards were set to patrol the castle walls. But there was a secret passageway into the castle which led to Mortimer’s bedroom. Together with a small band of men, the young king entered by the passageway, unseen.

The band cut down the two knights on guard and seized Mortimer. Isabella heard the scuffle and rushed into the room. When she saw what was happening, she screamed: ‘Have pity on gentle Mortimer!’ Regardless of her pleas Mortimer was taken to London, where he was hung, drawn and quartered on November 29. Isabella’s days of power and revenge were over. But she was not executed. Instead, she was retired to Castle Rising, in Norfolk.

King Edward III styled his court on the stories of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table that became very popular during his long reign. In 1348 Edward founded the Order of the Garter, an order of chivalry that still exists today.

Now, in Edward III, England could look forward to a respectable king for the first time in 20 years. The third Edward knew just how to keep his barons happy. He allowed them what they most wanted – to act as his advisers. He satisfied them even more by the splendid victories he and his son, Edward, the Black Prince, won over the French. The reign of Edward III was regarded as a glorious time in English history, despite the horrific Black Death, or bubonic plague, of 1349–1350, which killed a quarter of his subjects.

But Edward III lived too long. He became senile in the seven years before his death in 1377, aged 64, a sad shadow of the great warrior king he had once been.

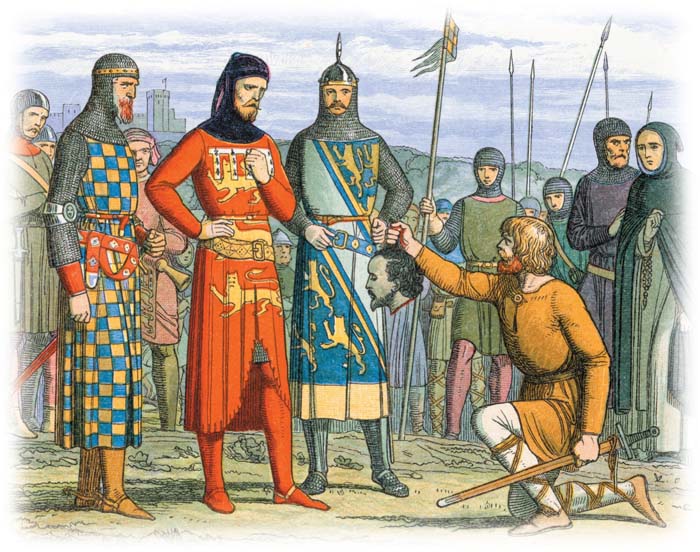

Three weeks later, King Richard II, Edward’s grandson and son of the Black Prince, was crowned at Westminster Abbey. He was 10 years old and at first seemed likely to be a good king. Four years later, Richard became a national hero when he rode out in person to confront the leader of the Peasants’ Revolt, Wat Tyler. Tyler had 60,000 followers with him. They were protesting about a poll tax of a shilling, which had to be paid by all adults aged 14 and over. It was far more than many poor peasants could afford, So they rebelled, and three days and nights of anarchy and bloodshed followed.

The young king must have known how violent and dangerous the rebels were. But he showed no signs of flinching. He calmed the situation by offering to withdraw the poll tax and give the rebels a pardon. But Wat Tyler approached Richard in such a menacing way that, fearful for the king’s safety, the Mayor of London, William Walworth, stabbed him with a sword. Tyler’s head ended up on a pike on London Bridge.

As Tyler fell to the ground, menacing murmurs came from the crowd. They moved forward, as if to attack the king and his officials. But young Richard kept his cool.

‘Sirs,’ he cried, ‘will you shoot your king? I am your captain, follow me!’

That was the end of the Peasants’ Revolt. Many people came to believe that England now had a brave young king who would one day match the great deeds of his father, the Black Prince. Or so it appeared on the face of it. But the face was deceptive. The fact that Richard had given in to the rebels, and had offered to grant them pardons after all the killing, destruction and chaos they had caused, was not a promising sign. It suggested that basically he was timid and would crack under pressure.

Added to that, Richard lacked the temperament of a traditional medieval king. He was not interested in military matters; he was over-emotional and hot-tempered. And, like King Henry III before him, he thought royal commands should be instantly obeyed without question.

Because Richard was underage when he came to the throne, a regency council ruled for him. Meanwhile, he stayed at home with his mother, Joan of Kent. But at every opportunity, he demonstrated what a thoroughly spoiled brat he was.

In 1382, he dismissed his chancellor, the Earl of Suffolk, for failing to obey his commands. The following year he told Parliament that he would choose any adviser he wanted and insisted that Parliament accept his wishes without question.

Before long, Richard had made rather too many enemies – powerful ones. He surrounded himself with advisers, making it clear that any opposition to his will would be regarded as treason. He invented new, more exalted terms of address: anyone speaking to him had to call him Your Majesty instead of the usual Your Grace.

Richard was obviously a tyrant. But English nobles had seen it all before. They knew what had to be done. In 1387, five so-called Lords Appellant – the Dukes of Gloucester and Hereford, the Earls of Arundel and Warwick, and Thomas Mowbray, Earl of Nottingham, took a stand. They persuaded Parliament to charge Richard’s most important supporters with treason. Richard was frightened. He gave in. He was forced to stand by and watch as four of his supporters, including his aged tutor Sir Robert Burley, were hung, drawn and quartered.

After this, Richard laid low. He did nothing to upset Parliament. He created a magnificent court and filled it with artists, writers and other harmless, non-military, types. But it was a smokescreen. All the while, Richard had been plotting his revenge.

Though only 14 years old, Richard II faced up bravely to Wat Tyler, leader of the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381. Tyler moved toward the young king in a threatening manner, and for this he was killed by William Walworth, Mayor of London.

By 1397, he was ready. Suddenly, without warning, the king ordered the arrest of the Lords Appellant. Three of them – the Duke of Gloucester and the Earls of Arundel and Warwick – were charged with treason. They were found guilty and executed. The Duke of Gloucester was arrested in Calais. He was smothered to death with a mattress.

King Richard had a special punishment in mind for the fifth Lord Appellant, Thomas Mowbray. It was one that would also get rid of Richard’s first cousin, Henry Bolingbroke. Richard had always been jealous of Henry, who was the epitome of a chivalrous knight. He was well educated and spoke several languages. He was admired at royal courts throughout Europe. And he was heir to the magnificent Duchy of Lancaster.

But Henry was far too trusting. He did not realize how devious Richard could be. Henry fell straight into Richard’s trap after Thomas Mowbray warned him that the king was plotting the downfall of the House of Lancaster. Bolingbroke accused Mowbray of speaking treason against Richard. Richard ordered that the dispute be settled the old-fashioned way: in a trial by battle.

On September 26, 1398, a huge crowd gathered to watch the combat. But as soon as Bolingbroke and Mowbray came out dressed for battle, Richard suddenly forbade them to fight. He exiled Thomas Mowbray for life. Henry Bolingbroke was exiled for 10 years.

Five months later, on February 3, 1399, Henry Bolingbroke’s father, John of Gaunt, died. The exiled Bolingbroke succeeded him as Duke of Lancaster. But he was a duke without rights or lands. As soon as John of Gaunt was dead, Richard announced that Bolingbroke would be banished for life. He ordered that lands belonging to the Duchy of Lancaster be handed over to the Crown.

Henry Bolingbroke soon struck back. Within a few weeks, he sailed home from France. He landed at Ravenspur in Yorkshire, in the north of England, on June 30, 1399. Bolingbroke claimed he had returned only to reclaim the Duchy of Lancaster. But there was a lot more at stake than that. Richard had finally gone too far. He had made too many enemies. And his enemies believed he was no longer fit to be King of England.

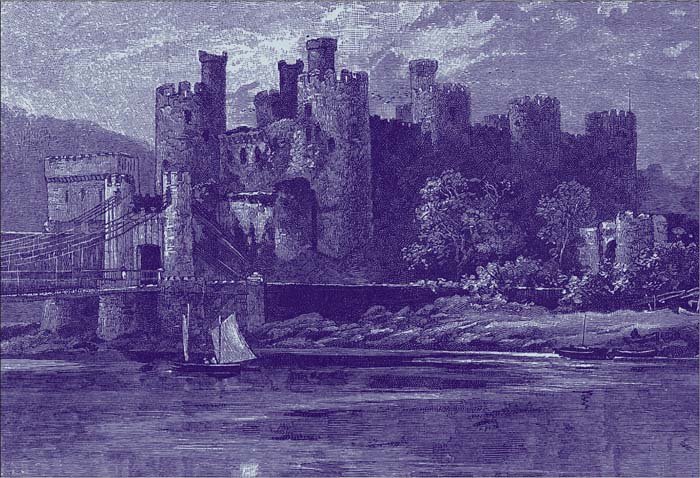

When Henry Bolingbroke landed in England, King Richard was in Ireland. He rushed back and shut himself up in Conway Castle, in Wales. But everyone had deserted him. He might have held out for a time inside the castle but for Thomas Arundel, brother of the executed Earl of Arundel, who assured him that if he came out he could make peace with Bolingbroke and still be allowed to remain king. It was a trap. On August, 20, 1399, as soon as King Richard set foot outside Conway Castle, he was ambushed and taken prisoner.

In this 15th century painting, the youthful Richard II sits with members of the Royal Council beneath an ornately decorated canopy. Richard was one of those kings who wanted absolute power – and paid the penalty for it.

Richard was taken to London, and imprisoned in the Tower. At the end of September, Parliament forced him to abdicate. Henry Bolingbroke claimed the throne of England.

This formidable fortress is Conway Castle, where Richard II attempted to hide from the forces of his cousin Henry Bolingbroke. The castle, whose ruins still exist, was fairly new in Richard’s time, having been built in the 13th century.

After that, Richard did not have long to live. He was taken to Pontefract Castle, in west Yorkshire. There, it was said, he was slowly starved to death. But his end might have been much more violent. It seems that on February 14, eight men armed with axes burst into Richard’s cell in the castle. Richard was eating dinner at the time. He immediately overturned the table and grabbed an axe. He set about his attackers and managed to kill four of them. But there was no doubt about the outcome. The remaining four assassins overwhelmed the ex-king and hacked him to death.

By this time, Henry Bolingbroke had already been crowned King Henry IV on October 13, 1399. But Henry was not happy. He was a usurper and had stolen the crown from its rightful owner, King Richard.

Henry was well aware of it. ‘God knows by what right I took the Crown,’ he said later. Strictly speaking, Henry had no right, and he was tortured by guilt for the rest of his life.

This picture shows King Richard II abdicating his throne, surrounded by knights and courtiers. It was painted at some time between 1400 and 1425 and comes from The History of the Kings of England by French chronicler Jean Creton.

The coronation of King Henry IV in 1399 was overshadowed by guilt and tragedy. Henry had usurped the English throne from his cousin, Richard II. The ex-king did not have long to live.