King Henry IV was always nervous, constantly watching his back. He could never be sure how long he would be able to hang on to his stolen throne.

![]()

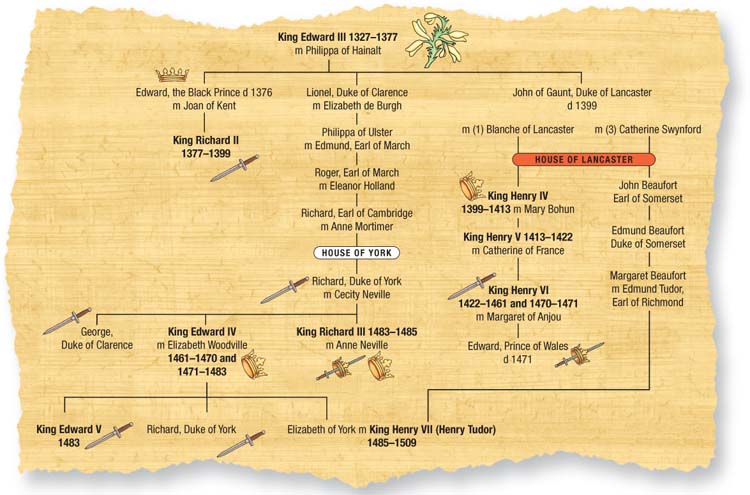

There were enemies lurking in the wings, many of whom had better claims to the throne. There was troublesome gossip, too. Henry had based his claim to the throne on the fact that he was the grandson of King Edward III. But according to hearsay, when King Edward’s wife, Philippa, lay dying in 1369, she made a confession. She revealed that in 1340, she had given birth to a daughter while in Ghent, in present-day Belgium. But by accident, Philippa had killed the young princess. Philippa was terrified the king would find out. So she had a boy, the son of a porter, smuggled into her apartments. Philippa passed this boy off as the child born to her in Ghent. King Edward was delighted with his new ‘son’. But the child’s real background was kept a secret. The boy grew up to become John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. John of Gaunt was Henry IV’s father.

If Henry IV had known the truth about his father, he kept it quiet. But there were other pressures. He was consumed by guilt over the murder of King Richard II. He tried to make up for it by paying monks to say prayers for Richard’s soul. But it did not make him feel any better. Having stolen the English crown, he had laid himself open to conspiracies. There were several plots to kill him. There were many rebellions against him. King Henry survived them all. But the strain showed. Henry suffered the first of several strokes in 1406. Tales spread that he was suffering from leprosy, though he more probably had eczema. He had epileptic fits. Henry IV was a physical and mental wreck when he died in 1413, aged 47.

Other Plantagenets had not forgotten their own claims to the throne. But they had to wait awhile to make their bids. There was no chance during the reign of Henry IV’s son and successor, King Henry V. Henry V was one of England’s greatest and most successful warrior monarchs and remains one of England’s national heroes. But when he died suddenly in 1422, aged 35, his son and successor was just the sort of king his rivals had been waiting for.

Henry VI was still in his cradle when he became king. He grew up weak and timid. Anyone could push him around. He had no military skills and hated bloodshed. Sometimes, he stopped the executions of criminals or traitors – he could not bear to see them die. But Henry was very religious. When he had to wear his crown on feast days, he felt he had committed the sin of pride. So he wore a hairshirt next to his skin to make up for it.

By rights, Henry should have been a monk, or better yet, a hermit. He found being king very hard going, so much so that in August 1453, he went mad. He no longer knew where he was, what year it was or even who he was. But somehow Henry had escaped from Ayscough’s influence long enough to conceive a child – Prince Edward, born in 1453. But when Edward was brought to him on New Year’s Day 1454, the king did not know why. He had forgotten he was the child’s father. Instead, he thought the father was the Holy Ghost.

All this was icing on the cake for King Henry’s rivals. A mentally unbalanced king with an infant heir was a double gift to anyone who wanted to seize power. As a mad king, Henry had to have a protector. So up stepped Richard, Duke of York. Ten years older than Henry, Richard was everything Henry was not – proud, warlike, ambitious and greedy.

Richard of York had his own claim to the English throne, a better one than either King Henry’s or Prince Edward’s. King Henry VI was descended from John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, the fourth surviving son of King Edward III. Richard of York was descended from Lionel, Duke of Clarence, King Edward’s third surviving son and John of Gaunt’s elder brother.

Richard’s first move was to have himself appointed the mad king’s protector, in March 1454. His next was to arrest Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset. Somerset was King Henry’s most powerful supporter. He was sent to the Tower of London.

Richard was also gunning for Queen Margaret. But he had to be careful. The bold, proud Margaret dominated her spineless husband. And beside being Queen Consort of England, she was also the mother of the heir to the throne. So however much Richard of York wanted to pack her off to the Tower of London, he did not dare.

King Henry VI was as unlike his father, Henry V, as it was possible to be. Timid and weak-minded where Henry V was valiant and strong, Henry VI was like his maternal grandfather, Charles VI of France; Charles was mad, and so was Henry.

Richard could remain protector only as long as King Henry’s madness lasted. It did not last very long. By Christmas 1454 he was better and Richard lost his job. But by now, the power struggle had gone too far. The Plantagenet royal family had already split into two rival factions: King Henry’s House of Lancaster and Richard’s House of York. The only way to settle their rivalry was by civil war.

Their struggle was called the War of the Roses. This was because the badge of Lancaster was a red rose and the badge of York was a white one.

This formidable-looking woman was Queen Margaret, wife of King Henry VI, who was completely dominated by her. Margaret was the driving force behind the resistance of the House of Lancaster to the claims of the House of York.

The war began with the battle of Saint Albans, Hertfordshire, on May 22, 1455. The House of York won. Henry VI was such a weakling that he even forgave Richard. Afterwards, Richard’s supporters were even given prestigious posts in the government. Richard could afford to let the harmless Henry VI remain king. As long as he did what he was told, that is. Henry VI was very good at doing what he was told. Even so, Richard took the precaution of imprisoning the king in the Tower of London.

But Richard had reckoned without Queen Margaret. Unlike her husband, she had never dreamed of giving in. Margaret raised an army and confronted the Yorkists at Wakefield, in Yorkshire. She won a great victory. Richard of York was killed in the fighting. Later, his skull was displayed from the walls of York, wearing a paper crown. Now the House of Lancaster had the upper hand – but not for long.

The Duke of York’s son Edward, aged 18, took over his father’s claim to the English crown. Of the two – Richard and Edward – Edward was by far the better man. He was handsome, charming and a fine military commander. Edward made far more headway than Richard had. He twice defeated the Lancastrian army. Afterwards, he was crowned King Edward IV of England on June 28, 1461.

King Henry, Queen Margaret and Prince Edward managed to escape to Scotland. But they arrived like beggars. On the way, Margaret was robbed of everything she had -– her plate, jewels and gowns. At one point, she was reduced to borrowing money. A chronicler wrote of how ‘the king her husband, her son and she had…only one herring and not one day’s supply of bread. And that on a holy day, she found herself at Mass without a brass farthing to offer; wherefore, in beggary and need, she prayed a Scottish archer to lend her something, who half loath and regretfully, drew a Scots groat from his purse and lent it to her.’

While the royal fugitives were in this terrible state, King Edward IV was living it up in London. He was very popular and women adored him. They did not have much trouble attracting Edward’s attention. He was a good-looking, lusty six-footer with a roving eye for beautiful women. Soon, everyone was gossiping about the number of women he had bedded. But before long, his roving eye got him into trouble.

Edward IV’s most powerful supporter was Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick. Warwick fancied himself as a ‘kingmaker’. Edward owed much of his success to Warwick. So, when Edward became king, this was payback time as far as Warwick was concerned. Warwick decided he was going to control the king. He planned a brilliant marriage for him, to a French princess. But Edward had other ideas. He had set his heart on an Englishwoman: Elizabeth Woodville, a 27-year-old widow with children. Edward wanted her badly. At first, he tried to seduce her, but she refused him. The gossips said Edward put a dagger to her throat, but she still resisted him. There was only solution: the king had to marry her.

But Edward was still very young and afraid of Warwick. So he married Elizabeth Woodville in secret on May 1, 1464. Edward managed to prevent Warwick from learning about his marriage for four months. When Warwick found out, at the end of September 1464, he was furious. The king had made him look like a fool. But that was not all. Elizabeth Woodville’s many relatives – including her seven unmarried sisters – were soon taking advantage and leeching off the king. They were given titles, grants of money, grants of lands – all of which Warwick had wanted for himself. Even more infuriating, King Edward preferred to go to the Woodville family for advice rather than to Warwick.

Meanwhile, in 1463, Queen Margaret and Prince Edward managed to escape to France. The deposed King Henry VI was left behind. He had to wander from one safe house to the next. Often, he disguised himself as a monk. But Edward IV’s spies were after him. They found him at Waddington Hall in Lancashire in July 1465. True to form, Henry did not put up a struggle. He was taken to London, and made a prisoner in the Tower for a second time.

Now, King Edward had Henry in his power. But he still had to deal with the Earl of Warwick, who was a dangerous man. So, in March 1470, King Edward accused the earl of treason. Warwick fled for his life to France. There, he contacted the woman who had once been his greatest enemy, Queen Margaret. Six months after Warwick and the Queen had joined forces, Warwick brought an army to England. Margaret was to follow on with another army. Warwick was determined to topple Edward IV and pay him back for insulting him. Warwick pulled it off. King Edward was captured after a battle at Northampton, in central England.

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick – ‘Warwick the Kingmaker’ – was the most powerful English noble during the Wars of the Roses. In 1470, Warwick had the Yorkist king, Edward IV, imprisoned and the Lancastrian Henry VI locked up in the Tower.

Now, Warwick really was a kingmaker. He had King Edward IV imprisoned in his castle of Middleham in northern England. King Henry VI was in the Tower of London. Warwick could do what he liked with both. Warwick chose to put Henry VI back on the throne. He was easier to control than Edward IV. After all, he was called Henry the Hopeless, the king who would do as he was told.

But King Edward escaped from Middleham Castle and managed to reach France. He did not stay there long. Soon Edward was back in England, this time with a new army of his own. Edward’s forces met Warwick’s at the battle of Barnet, just north of London, on April 14, 1471. Warwick had brought King Henry from the Tower and sat him by a tree to watch the fighting. What Henry saw, however, was Warwick’s defeat. Warwick fled from the battlefield. But the triumphant Edward IV was not about to let him get away. The earl was pursued and killed. Poor King Henry was then seized and sent back to the Tower for the third and last time.

Warwick the Kingmaker was killed at the Battle of Barnet when Edward IV’s forces defeated the Lancastrians. Warwick began the Wars of the Roses fighting for the Yorkists, but he changed sides because of a quarrel with Edward IV.

The same day, Queen Margaret and Prince Edward returned to England. But Edward made short work of Margaret and her army. At Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire on May 4, 1471, Queen Margaret was defeated. Seventeen-year-old Prince Edward ran away from the battle, but was pursued and killed.

Margaret was devastated. But for her, worse was to come. The victorious King Edward IV could not afford to let Henry VI live any longer. On the night of May 21, 1471, around midnight, Henry was stabbed to death in his cell at the Tower of London. One of the killers was Richard, Duke of Gloucester, Edward IV’s youngest brother.

Later, Henry’s body was publicly displayed so everyone would know he was dead. According to the official story he had died naturally, ‘of pure displeasure and melancholy’. But there was also talk that blood had spurted from his wounds, signifying what had really happened to him.

This was the end for Queen Margaret. She had lost everything – her husband, her son and her crown. Her father, King René of Sicily, ransomed her and she lived in France until her death in 1482.

The following year, Edward IV’s days of enjoying high living and his scores of mistresses caught up with him. He suffered a stroke and died on April 9. He was only 42. He left his throne to his 12-year-old son, who became King Edward V.

Edward V was an invitation for trouble. With a civil war simmering, the last thing England needed was a boy king. No king could actually rule until he grew up. A royal council ruled for him. And this gave ambitious men ideas about seizing power for themselves. The most ambitious of them was Richard of Gloucester.

Queen Margaret was taken prisoner after the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471 and her son, Prince Edward, was killed. Later Margaret’s husband, Henry VI, was murdered in the Tower of London.

‘Woe to the land that’s governed by a child!’ Shakespeare wrote in his Richard III. This was certainly true for Edward V. Robbed of his throne by his uncle, Richard III, Edward became the third English king to be murdered in the 15th century.

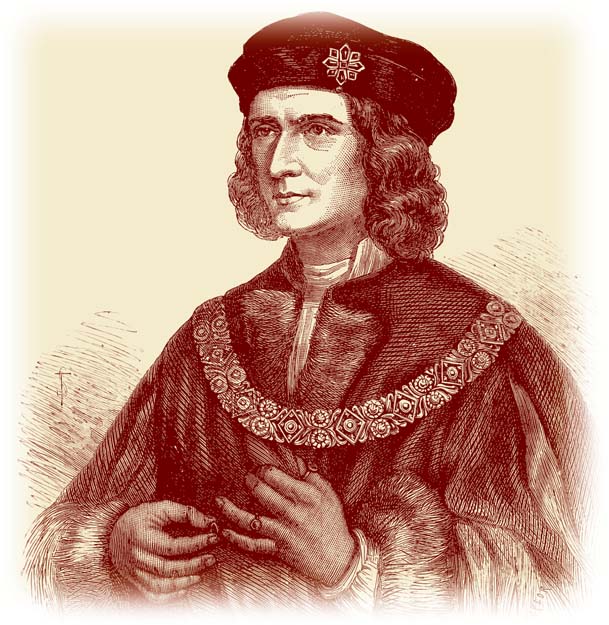

Richard of Gloucester would go down in English history as the evil uncle, a deformed monster and just about everything else bad. This picture of Richard was pure propaganda. It was dreamed up by the Tudor royal family, which took over from the Plantagenets after the Wars of the Roses ended in 1485.

Like all propaganda, it was more powerful than true. The Tudors did a very thorough job in creating Richard’s demonic image. They turned him into a hunchback. They said he had been born with teeth and born breech – legs first – which was considered extremely bad luck in highly superstitious times when anything ‘unnatural’ was seen as the work of the devil. And by the time the Tudors had finished with him, no one doubted Richard was one of the devil’s own.

But Richard was not a hunchback. His portraits show there was nothing wrong with him. During the Wars of the Roses, he had stuck loyally by his brother King Edward IV. Edward trusted Richard so completely that he sent him to rule the troublesome north of England. He ruled it well and became very popular. Even today, more than five centuries later, people in the north of England look back on Richard of Gloucester with affection.

Elsewhere, however, the Tudor smears about Richard stuck – firmly. So did the idea, encouraged by the Tudors, that Richard had murdered his way to the throne. The list of accusations was a long one. To begin with, he allegedly had murdered King Henry VI in the Tower of London in 1471. The same year, so the story went, Richard killed Henry VI’s son, 17-year-old Prince Edward, at the battle of Tewkesbury. Seven years later, Richard was blamed for the death of his own elder brother, George, Duke of Clarence, also in the Tower of London. It is a well-known story that Richard drowned George in a butt of Malmsey wine. The simple truth was that George was a habitual traitor, and King Edward IV had had him executed.

After George, only two people stood in Richard’s way: the boy king Edward V and his 10-year-old brother, Richard, the Duke of York.

On May 1, 1483, Richard of Gloucester abducted Edward V while the boy was on his way to London. Richard had always hated Queen Elizabeth Woodville and her family. When the queen heard the boy king was in Richard’s clutches she took fright and bolted, taking her younger son, Richard, Duke of York with her to the safety of Westminster Cathedral. There, under the protection of the Church, Richard could not get at her. Or so the queen thought. But Richard found a way. On June 16, he threatened the Queen so fiercely that she let him take the young Duke of York away. That was the last she saw of him. She never again saw her elder son, Edward V, either. From time to time, the boy king and his brother were seen playing in the gardens of the Tower. But by July 1483, the sightings had stopped. They were never seen alive again. There was no funeral. The boys had simply vanished. Later, they became known as the tragic Little Princes in the Tower.

Meanwhile, Richard of Gloucester made preparations to seize the throne. He propagandized that Edward V and the Duke of York were illegitimate. This was because when their father married their mother, he was already betrothed to another woman. In other words, the marriage was illegal. It was a terrible smear on the boys, but Londoners just about believed the story. Richard was proclaimed King Richard III. His coronation took place on July 6, 1483.

It is possible that just then the boy king and his brother had still been alive. But once their uncle had usurped the throne, they were not going to be permitted to remain alive for long. The boy king and his brother were killed, possibly on September 3, 1483.

Shakespeare’s Richard III is one of the great tragic parts in British theatre. Ian McKellen played the role in a film made in 1995. Forty years earlier, the acting legend Laurence Olivier had played the part of Richard III on screen.

As a usurper, King Richard III had many enemies. After the deaths of the Princes in the Tower, people found it easy to believe he would do anything to retain the stolen throne. When his wife, Anne Neville, died in 1484, people said that Richard had poisoned her so he could marry his niece Elizabeth, daughter of King Edward IV. That marriage would have strengthened Richard’s hold on the throne.

During a propaganda campaign against him, the Tudors presented King Richard III as an evil hunchbacked monster who was born unnaturally, with teeth. This portrait shows there to be nothing wrong with Richard.

But that was just gossip. Richard’s real enemy was Henry Tudor. Henry was the chief claimant to the throne from the House of Lancaster. He had spent most of his life in exile. For years, Henry moved from one secret place to another, dodging the thugs that Yorkists had sent to kill him. He escaped them all. And in 1485, he set out to remove Richard from his stolen throne.

On August 7, Henry Tudor arrived with an army of 4,000 to 5,000 men at Milford Haven in South Wales. It was not a large force. So, on August 22, when Henry Tudor confronted Richard and his army of 12,000 men at the battle of Bosworth, in Leicestershire, his chances did not look good. But what neither Richard nor Henry knew was that three of Richard’s commanders were about to desert him.

This is the seal of King Henry VII, the first Tudor monarch. It shows King Henry with the royal coat of arms on either side. An official document was only valid if it bore this seal.

One, Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, refused to move his troops when ordered. Two others, Sir William Stanley and his brother Lord Stanley, planned to switch sides. Richard was doomed.

All he could do in the circumstances was make a desperate attack. It proved to be suicidal. With a small force of men, Richard spurred his horse through the front line of Henry Tudor’s army. His aim was to reach Henry and kill him. Richard never got that far. He managed to kill Henry’s standard bearer, but Henry’s soldiers closed in and trapped him. Before long, Richard was pulled from his horse and killed. Afterwards, his naked body was slung over the back of a packhorse. Then it was taken to Leicester for burial.

Richard III was indeed the unlucky 13th Plantagenet king of England. With his death, the Wars of the Roses came to an end. A famous story recounts that, during the battle, Richard’s crown fell from his head and rolled in the dirt. It was later found hanging from a bush. Supposedly, Lord Stanley picked up the crown and placed it ceremoniously on Henry Tudor’s head. After an eventful 330 years, Plantagenet rule in England had finally come to an end. As Henry VII, Henry Tudor became the first king of a new dynasty.

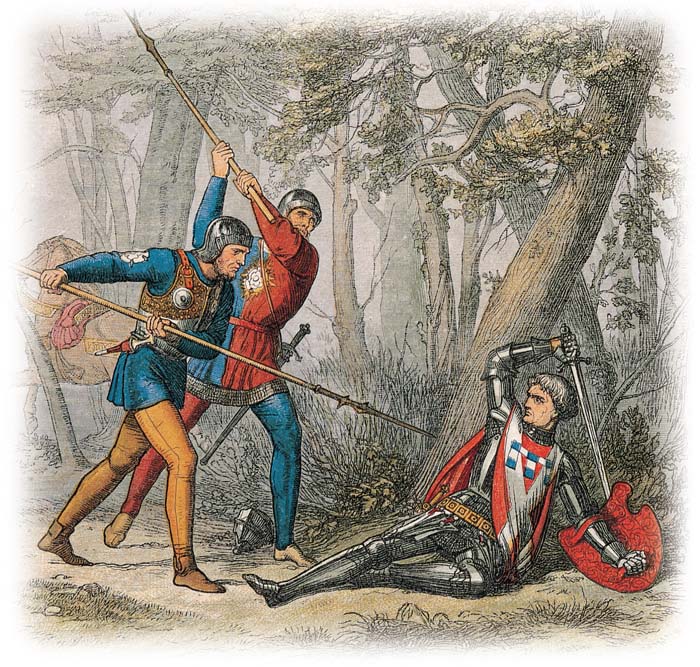

At the battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, two of Richard III’s most powerful supporters changed sides. Richard was doomed. He then staked everything on a desperate attempt to reach his rival, Henry Tudor, and kill him, but he failed.

Cardinal Wolsey was Henry VIII’s chief minister. The two were friends for the first twenty years of the king’s reign, but Wolsey’s relationship with Henry was soured by his failure to persuade the Pope to grant Henry a divorce.