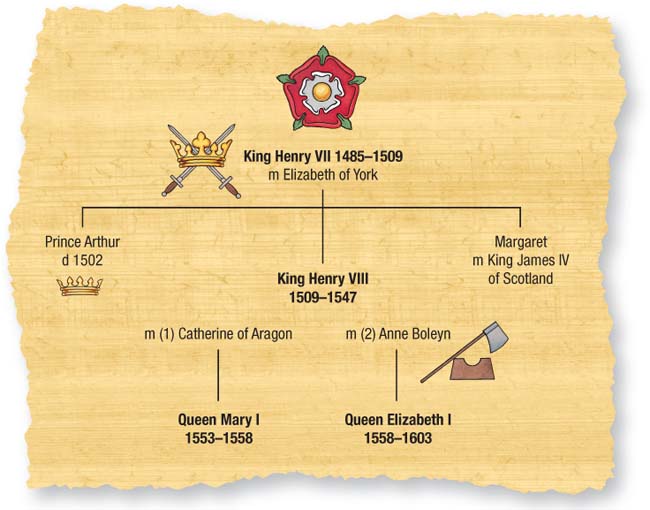

The Plantagenet dynasty was gone. Now, the Tudors were in charge. But the Plantagenet family was still around. Henry VII, first king of the new Tudor dynasty, tried to heal the rift that had led to the Wars of the Roses.

![]()

After the battle of Bosworth, he married Elizabeth of York, daughter of King Edward IV. This, King Henry hoped, would finally reunite the rival houses of York and Lancaster. But there was not a chance. The Yorkists were still out for revenge, and would try any trick in the book to dislodge the Tudors.

In 1487, a young man arrived in Ireland claiming to be Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Warwick. His real name was Lambert Simnel, son of a joiner in Oxford. The true earl was the son of George, Duke of Clarence, brother of King Edward IV. That gave Simnel a putative claim to the throne of England. He staked this claim on May 24, 1487: that day, he was crowned ‘King Edward VI’ in Dublin Cathedral. For a crown, the ‘king’ had to use a gold circlet ‘borrowed’ from a statue of the Virgin Mary.

When Henry VII heard about it, he responded vehemently. He knew this ‘King Edward VI’ was an impostor because he had the real Earl of Warwick imprisoned in the Tower. To prove Simnel was a sham, Henry brought the real Earl of Warwick out of the Tower. He made a big show of parading him through the streets of London so everyone would know who he was. But this did not deter Simnel and his supporters. They landed an invasion force in Lancashire, in the north of England, on June 4, 1487, then marched south toward London.

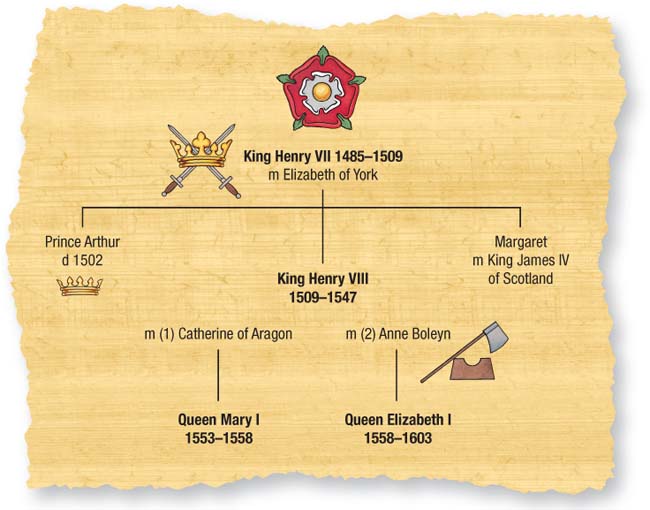

Perkin Warbeck, the second royal impostor of Henry VII’s reign, is seen being put in the pillory where anyone was free to abuse him or throw missiles. Unlike the first impostor, Lambert Simnel, Warbeck was eventually executed.

King Henry was waiting for them at Stoke in Nottinghamshire, and won the battle that ensued. He also captured Lambert Simnel. Arguably, Simnel deserved to be executed for treason, but Henry decided to shame him instead. So he made Simnel a servant in the royal kitchens.

Lambert Simnel was not the only false claimant to the crown. In 1491, another young man turned up in Cork, Ireland, claiming to be the Earl of Warwick. Then he changed his story and said he was an illegitimate son of King Richard III. Finally, he settled for pretending to be Richard, Duke of York, one of the Princes in the Tower. The young Duke of York, so he declared, had not died in 1483; he had escaped and somehow made his way to safety. And here he was, in Ireland, ready to claim the throne of England that was rightfully his.

The young King Henry VIII was handsome and personable, with a flair for dancing. It was only later that he became a bitter, overweight, cruel and much feared despot with a reputation as a wife killer.

The ‘Duke of York’ was, of course, another impostor. His real name was Perkin Warbeck. He was son of a customs official in the Netherlands. Warbeck was 19, about the same age the real duke would have been if he were still alive.

For Henry VII, this impostor was even more dangerous than Lambert Simnel. Henry sent agents to scour Europe and find him. Henry need not have bothered, for Warbeck fell straight into his hands. In 1497, he landed in Cornwall, in southwest England, with a force of 120 men. He gathered support and before long had raised an army of 8,000. Now, he felt secure enough to declare himself King Richard IV.

But Warbeck was no military leader. His followers were a rabble, with no idea how to fight a battle. Most of them fled when they encountered Henry’s army at Taunton in Somerset. After that, Warbeck was easily captured and forced to confess that he was not really Richard IV. At first King Henry was kind to him. He made him one of his courtiers. It was only when Warbeck tried to escape that he was dispatched to the Tower of London.

That did not cure him. In 1499, King Henry’s spies discovered that Warbeck and the real Earl of Warwick were planning to escape. It was the end for both of them. Warbeck was hanged. Warwick was beheaded.

There were no more impostors during the reign of King Henry VII, which ended with his death in 1509. But his successor, King Henry VIII, was obsessed with the Plantagenets and their conspiracies. As king he set out to get rid of every Plantagenet he could lay his hands on.

The Byward Tower at the Tower of London was meant to be the last in a series of strongholds for the complex. Even today, nighttime visitors have to give the right password to the sentry on guard before they can enter the Byward Tower.

Henry VIII’s chief target was the De la Pole family. They were descended from George, Duke of Clarence, the brother of Edward IV and Richard III. Their claim to the throne was somewhat distant, but legitimate all the same.

During Henry’s reign, the senior member of the family was Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury. Cardinal Reginald Pole, son of the countess, managed to escape into exile in Europe. But his brother Geoffrey Pole was arrested. He gave evidence against his mother the countess, another of his brothers, Henry Pole, Lord Montague and two other relatives, Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter, and Sir Edward Neville. All were executed.

By this time, Henry had gained a very bloodthirsty reputation. Much later, he was given the nickname ‘Bluff King Hal’ – jolly, friendly, kindly and always good for a laugh. The real King Henry VIII hardly matched that description. In truth he was terrifying. By 1541, Henry had married four wives, and each had had time to discover what he really was: a cruel despot who would not hesitate to torture and execute anyone in his way.

Henry VIII’s first wife was Catherine of Aragon, daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. Catherine had been married before, to Henry’s elder brother Arthur. But Arthur died in 1502, soon after the wedding. Little did Catherine know that this first marriage would later provide Henry with ammunition against her. Catherine was six years older than Henry. She had to wait for him to grow up before he could marry her. He was 18 and already King of England, and she was 24 when the ceremony took place on the 11th of June, 1509.

At first, Henry and Catherine were very happy. ‘My wife and I be in good and perfect love as any two creatures can be,’ Henry wrote to Catherine’s father, King Ferdinand. Their first child, a son, was born on New Year’s Day, 1510. His delighted father held a tournament in celebration at Richmond Palace. Then, tragedy struck. The baby prince lived for only seven weeks. Henry and Catherine were devastated. But things would only get worse.

Catherine had several more children. All except one died in infancy or were born dead. The only survivor was a daughter, Princess Mary, born in 1516. Catherine had been a beautiful woman. But all those deaths had worn her down. By age 30 she had lost her looks and her figure. Even her hair had turned silver. She became intensely religious. Most of her time was spent at prayer. She even wore a hair shirt under her gowns, in the manner of an ascetic or saint.

None of this appealed much to Henry. He liked young, lively women and Catherine was no longer young nor lively. But most of all, he longed for a son to succeed him.

Henry loved his daughter Princess Mary and was very proud of her. He also spoiled her. But England was not yet ready for a reigning queen. Henry needed a new, young wife who could give him the son he so desperately craved.

In 1522 Anne Boleyn came to court as one of Queen Catherine’s ladies-in-waiting. She was 21, stylish, sexy and sophisticated. Although not beautiful, Anne knew how to attract men. She was a tremendous flirt with a few tricks up her sleeve. Even King Henry was taken aback by how much she knew about the arts of love.

Anne Boleyn was also ambitious. Once she arrived at the royal court, she aimed for the top prize: Henry VIII himself. But she was not going to make the same mistake as her sister Mary, who had once been Henry’s mistress. Mary had learned a great deal at the royal court in France, which was in fact little more than an upscale brothel. She joined in the fun with such zest that even the French king, Francis I, considered Mary little more than a common prostitute. When Henry took her over, he thought he could benefit from such an experienced mistress. But maybe he hadn’t been able to keep up with her: Anne Boleyn said later that he was not a very good lover. Even so, Henry had tired of Mary Boleyn after two years and thrown her out. Anne was not going to let that happen to her.

In 1526, Henry asked Anne to become his mistress. He was flabbergasted when she turned him down. He kept on trying, but the more he tried, the more Anne refused. He wrote her passionate love letters. She took her time answering, just to keep him on the hook. But she would not budge. She knew she had driven the King of England into a frenzy of desire – just where she wanted him.

Catherine of Aragon, the first wife of King Henry VIII, was born a Spanish princess in 1485. She was trained and educated for her role as a Queen Consort and was capable of taking over from the king when he was absent abroad.

Meanwhile, Henry was having big trouble with Catherine. She had always been a great lady; calm, modest and gracious. It would not be difficult to get around her, or so Henry believed. Then, he could have Anne Boleyn. But in June 1527, when he told Catherine he wanted a divorce, he found out differently.

Henry had discovered a good reason for divorcing Catherine, a religious reason that should have done the trick. The ‘Prohibition of Leviticus’ in the Bible forbade marriage between a man and his brother’s widow. King Henry could always persuade himself that whatever he wanted he should have. And the Prohibition of Leviticus persuaded him that his marriage to Catherine had been cursed. That was why all their sons had died.

Catherine, seen in the foreground, knew about Henry VIII’s romance with her lady-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn. In this 20th century illustration Henry and Anne are seen chatting in the background while a tearful Catherine walks alone in tears.

Catherine burst into tears when he told her. But that did not mean she was giving in – far from it. When she stopped crying, Catherine told Henry that he could not have a divorce. She claimed that her brief marriage to Prince Arthur had never been consummated and therefore had not been a marriage at all. The Prohibition of Leviticus did not, therefore, apply. This was the start of one of the most ferocious marital contests in English history.

Now that it was war, husband and wife lined up their ammunition. Henry tried to gather evidence that Catherine and Prince Arthur had slept together. He did not get far with that line of inquiry. Some courtiers said they had, others said they had not.

Henry was furious. But he tried to get around the problem by sending his chief minister, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, to Rome. Wolsey’s orders were to obtain permission from the Pope for Henry to marry Anne Boleyn. But Catherine had better firepower. She had powerful relatives in Europe. The mightiest was her nephew, King Charles I of Spain, who had the Pope, Clement VII, in his pocket. There was no way Henry was going to get what he wanted from him.

When Catherine told King Charles what was happening, he sent a stern warning to Henry to forget about the divorce or prepare for the consequences. But Charles had other things on his mind, such as French invasions of Spain and his own lands in Italy. These problems distracted the Spanish king long enough for Pope Clement to slip his leash. Clement agreed to send a legate, Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio, to England to judge the royal divorce case.

Until 1529 Cardinal Thomas Wolsey was a very powerful man. He is shown here receiving petitions and requests from people who treat him with extreme deference, bowing and kneeling as he passes by.

Pope Clement was a cautious man. He told Campeggio to waste time by taking the longest route to England. When he arrived, Campeggio was told, he should start by trying to patch up the royal marriage. Above all, Campeggio was to delay, delay again, and make no decision.

The Pope need not have taken the trouble. When Campeggio reached England after a journey of four months, he found that Henry and Catherine were still at odds. Neither would back down. Catherine fought Campeggio all the way. No, she told him, she would not enter a nunnery. No, she would not leave the court. And she would rather die twice than admit her marriage to Henry was invalid.

In this 19th century illustration, Cardinal Campeggio, the papal legate, questions Queen Catherine at the inquiry into the divorce while her husband, King Henry (seated) glowers in the background.

Campeggio had no better luck with King Henry. He wanted Anne Boleyn and that was that. Clearly, it would be a fight to the finish. All the same, the cardinal convened a special court on June 21, 1529. He ordered King Henry and Queen Catherine to attend. But after they arrived, it was Catherine who captured all the attention.

In her speech to the court, she asked for justice as Henry’s ‘true and obedient wife.’ Then, she asked – in all innocence – how she had offended him. It was a great performance. At the end, Catherine swept out of the court. Henry commanded her to return. She refused.

Henry exploded. In his fury, he turned on Cardinal Wolsey, his faithful minister since the beginning of his reign. But Wolsey’s devotion did not matter now. What mattered was that he had failed to persuade the Pope to let Henry marry Anne Boleyn. Anne had already been running a slander campaign against Wolsey. She had Henry spellbound, and it was only a matter of time before he accused Wolsey of high treason. Wolsey was so upset he became seriously ill. In 1530, he died on his way to London where the treason trial was to have taken place. Anne Boleyn celebrated his death with a court entertainment called The Going to Hell of Cardinal Wolsey.

Henry was disgusted. But he was so scared of Anne and her sharp tongue that he let her get away with it.

By now he had gone too far with the divorce to walk away from it. Meanwhile, King Charles of Spain had thrashed the French invaders. So the Pope was in his power again and Henry would have no joy there. He was also thoroughly bedeviled by his women. Catherine still defied him. So did their daughter, Princess Mary. And Anne Boleyn continually nagged him to marry her.

In 1531, egged on by Anne Boleyn, Henry separated Catherine from their daughter Mary. Anne believed the two had conspired against the king. Splitting them up might weaken their resistance. The king ordered Catherine to More House in Hertfordshire. Mary was sent to the royal palace at Richmond, Surrey. Mother and daughter would never see each other again.

After that, Catherine was moved from one house to the next. Each was more decrepit and unhealthy than the last. Wherever she was, Henry sent counsellors and other officials to crack her resistance. They tried threatening her. They terrorized her. They told her terrible things would happen to Princess Mary if she did not change her mind. They got nowhere.

Meanwhile, Anne Boleyn was showing off in London. She said she would rather see Catherine hanged than acknowledge her as Queen of England. Henry demanded that Catherine hand over her jewels. When she did so, he gave them to Anne.

Anne was already living in the royal apartments that had once belonged to Catherine. She had her own ladies-in-waiting. It was as if she were Queen Anne already. She was constantly with the king. They dined together, danced together, went hunting together. They did everything except sleep together. This stoked up Henry’s passion even more. In addition to jewels, he sent Anne other luxurious gifts, such as hangings in cloth of gold and silver, and lengths of embroidered crimson satin. Henry also gave her a title – Marquess of Pembroke: lands worth £1,000 a year went with it. Anne Boleyn was riding high.

Born to a poor family in Ipswich, the son of a butcher, Thomas Wolsey rose to the greatest heights possible: he effectively governed England for the first twenty years of Henry VIII’s reign. He also had ambitions to become Pope.

But she did not intend to hold off Henry forever. Around November or December 1532, she at last let the king take her to bed. A month or so later, she was pregnant. This was probably no accident. Anne was determined to be queen. Her pregnancy was a warning to Henry to put his foot down and get that divorce. Henry’s response to Anne’s demands was to change England and the lives of its people forever.

This gold medal was minted in 1545 to commemorate Henry VIII’s new role as head of the English church in place of the Pope. Henry appears on the medal wearing an ermine robe and a cap and collar studded with jewels.

At this time in Europe, the Reformation was underway. Protestants were breaking away from the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church. Now, it was Protestants against Catholics. King Henry was a sincere Roman Catholic, but he broke with Rome just the same. The Pope would not give him a divorce. So he made himself Supreme Head of the Church of England and granted himself the divorce he wanted.

King Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn were married in secret on January 25, 1533. Henry had given Catherine one last chance to give up her rights and title as queen. She had still refused. The outlook was bad for Catherine. After the break with Rome, the English church no longer needed the Pope’s agreement for anything. So it was easy for Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, to declare that Catherine’s marriage was at an end. At the same time, he decreed that Anne’s marriage was legal.

Catherine was ordered to stop calling herself ‘Queen of England’. She had to use the title ‘Princess Dowager’ instead. It was a terrible insult. Once more, Catherine refused. When Henry sent her a document changing her title to Princess Dowager, she returned it with the new title crossed out. The furious Henry threatened her. Still Catherine held out.

By now, the struggle between Henry and Catherine had gone beyond a marital spat. Catherine’s nephew, Charles of Spain, threatened to invade England. Moreover, Henry’s subjects did not like Anne Boleyn, but loved Catherine. Whenever Catherine had to move from one house to the next, people gathered by the thousands to cheer her. Anne was often booed in public. There were public demonstrations against Anne. She was called a ‘whore’ and a ‘witch’. A huge crowd gathered when she rode through the streets of London on the way to her coronation on June 1, 1533. The crowd had been ordered to cheer. Instead, they yelled: ‘Nan Bullen shall not be our Queen!’

By this time, the King had become desperate. Catherine and Mary were still defying him. As for Anne, she was giving her husband a hard time. Anne was a real tartar, demanding and vengeful. She threw one tantrum after another. Her child, born on September 7, 1533, turned out to be another girl – the future Queen Elizabeth I. There were no celebrations.

After the downfall of Cardinal Wolsey, Henry took over his magnificent palace, Hampton Court, by the River Thames. He was astounded and also infuriated at the luxurious fittings and decorations, like those seen here in the Great Hall.

Henry felt he had been made the laughingstock of Europe. In England, he had to face fearful slanders. It was said that the king was living in sin with Anne, that she was no more than a wicked woman with loose morals who deserved to be burned at the stake. Princess Elizabeth was condemned as illegitimate. Before long, Henry decided it was Anne’s fault that their child was not the son he wanted. He began to call his second marriage his ‘great folly’.

It certainly looked that way. Henry had no control over Anne. She would insult him in front of his courtiers. She never apologized. All Henry could do was to complain to Anne’s father, Sir Thomas Boleyn, that Queen Catherine had never used such language to him. The pressure brought out Henry’s natural cruelty. He began to mull over the idea of getting rid of Anne. But, as long as Catherine lived, he was stuck with her.

Catherine, however, had not much longer to live. By 1534, it was said she had dropsy. In fact, she was suffering from cancer. ‘So much the better’, retorted the king when he heard about it. Catherine was then shortening whatever life she had left by refusing to eat. She was afraid Henry was going to poison her.

Meanwhile, there was opposition to his second marriage. Henry’s answer was to execute anyone who spoke out against it. One of the condemned was Sir Thomas More, scholar and author, and once Henry’s chancellor. More was beheaded on Tower Hill on July 6, 1535.

By that time Catherine was dying. Somehow she hung on over Christmas 1535 and into 1536. But she was in a terrible state. She was so wasted, wrote ambassador Chapys, ‘that she could hard sit up in bed. She couldn’t sleep. She threw up what food she managed to swallow.’ Finally, she passed away on January 9, 1536.

Sir Thomas More, Henry’s former chancellor, refused to acknowledge him as the head of the English church. Found guilty at his trial for high treason, More was executed in 1535. Here he is, saying good-bye to his daughter, Margaret Roper.

The Tower of London had been used as a palace, a prison and a place of execution since Norman times. Here Henry’s second wife, Anne Boleyn, would meet her end.