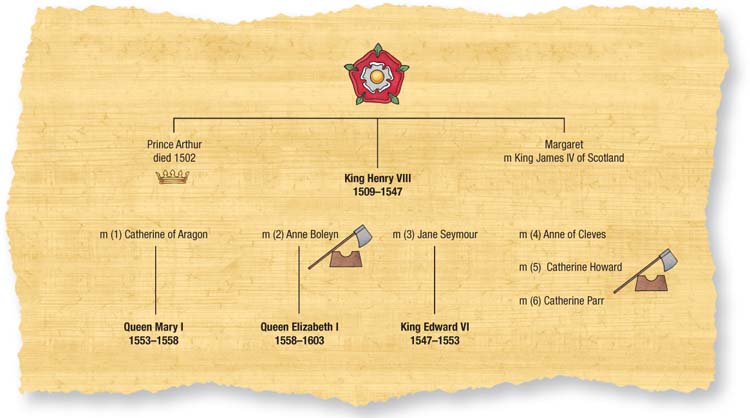

Free of Catherine at last, King Henry began to think of ways to get rid of Anne. He was tired of clever, educated women like his first two wives. What he wanted now was a nice, placid girl who would not argue with him.

![]()

He found his new wife in the same place he had found Anne Boleyn: among the queen’s ladies-in-waiting.

Jane Seymour, daughter of Sir John Seymour, appeared to fit the bill perfectly. She seemed quiet and modest with a nondescript personality. Nor was she very pretty: she had a long chin, a tight mouth and a large nose. She could hardly read and write, beyond signing her own name. Yes, dull, plain Jane Seymour was just what Henry wanted.

But Jane Seymour was much more calculating than Henry could have known. She quickly gathered that Anne Boleyn was on the way out. This was Jane’s cue to step in smartly. She played the game perfectly. She accepted gifts Henry sent her. But she would not open his letters or accept money. Once, she kissed a letter sent to her on the king’s behalf. Then she handed it back to Sir Nicholas Carew, who had brought it to her. She also gave back the purse of gold that came with it. Jane asked Sir Nicholas to tell the king she would only accept money when God sent her a husband. Subtle hints were not Jane’s style.

Poor fool Henry was taken in again. He was delighted that Jane had proven so virtuous and demure. But Anne Boleyn was not so easy to deceive. She knew exactly what was going on.

Jane heartlessly rubbed Anne’s nose in the dirt. Henry sent Jane a portrait of himself in a locket. In front of Anne, she toyed with it. She opened and closed it and cooed over it. Anne was so furious that she tore the locket from Jane’s neck. Several times she slapped Jane’s face when gifts and messages from Henry arrived. Jane made no secret of where they had come from.

Now that Henry had found a new love, there was only one hope for Anne: to produce the longed-for son. She became pregnant three more times. She lost two of the babies, but near the end of 1535, she was pregnant again. Henry began to hope, but still carried on with Jane. Then, on the afternoon of January 29, the day Queen Catherine was buried, something happened to push Anne over the edge: she found her rival sitting on the king’s knee.

Anne flew into such a wild fury that Henry began to fear for the child she was carrying. He tried to calm her down. But she raged on and on. A few hours later, the inevitable happened. Anne miscarried. When it was examined, her child appeared to be a son. For Anne, it was the end. She had a violent argument with the king. Each of them blamed the other for the miscarriage. Eventually, the king stormed out, vowing Anne would have no more sons by him.

This time, Henry did not have divorce in mind. Anne, he knew, would plague him for as long as she lived. There was only one answer: Queen Anne Boleyn had to die.

Henry chose his weapons. He would accuse Anne of witchcraft, adultery and plotting his death. All these charges carried the death penalty. Henry set his chancellor, Thomas Cromwell, to gather the ‘evidence’ together. Thomas Cromwell was a highly inventive man. Gossip and reports from spies formed part of his dossier against Queen Anne. The rest he made up. Henry now learned that Anne supposedly had had four lovers: three courtiers and a court musician, Mark Smeaton. Cromwell also ‘discovered’ that Anne had committed incest with her brother, Lord Rochford.

As per usual in Tudor times, torture was used to obtain Smeaton’s confession. The others all denied the charges. Henry knew perfectly well that Anne was being framed. But he was satisfied. He ordered Anne’s arrest on the evening of May 2, 1536. She was taken to the Tower of London in a paroxysm of fear. She had to be helped out of the barge that took her to the Tower. By the time she stepped inside she was hysterical and sobbing wretchedly. In mid-May, her ‘lovers’ went on trial. The evidence given was full of holes. Anne and her ‘lovers’ could prove they were all in different places when the alleged adulteries had taken place.

It did not matter. Henry could always fall back on the supposed plot to kill him. It was ‘guilt by accusation’, but it did the trick. The four ‘lovers’ were all found guilty. They escaped the penalty for traitors: hanging, drawing and quartering. Instead, they were beheaded on Tower Hill on May 17, 1536. The same afternoon, Anne’s marriage to Henry was annulled.

At her own trial, Anne was calm and dignified. She denied everything. But it did her no good. She was found guilty and condemned to death. From her apartments at the Tower, she watched workmen constructing her scaffold. They worked all night and by 9:00 A.M. the next morning, May 18, the scaffold was ready. The queen was executed the following day.

While Anne’s trial was going on, Henry was making arrangements to marry Jane. Their engagement was announced on the same day Anne Boleyn died. Eleven days later, on May 30,1536, Jane became Henry’s third wife and queen in a ceremony at Whitehall Palace. Jane was also Henry’s third chance to have the son he so greatly desired.

Anne Boleyn was the fiery, sexy and ambitious second wife of King Henry VIII. She got away with treating him with little respect, but fell foul of fate when, instead of the longed-for son, her child born in 1533 turned out to be a girl.

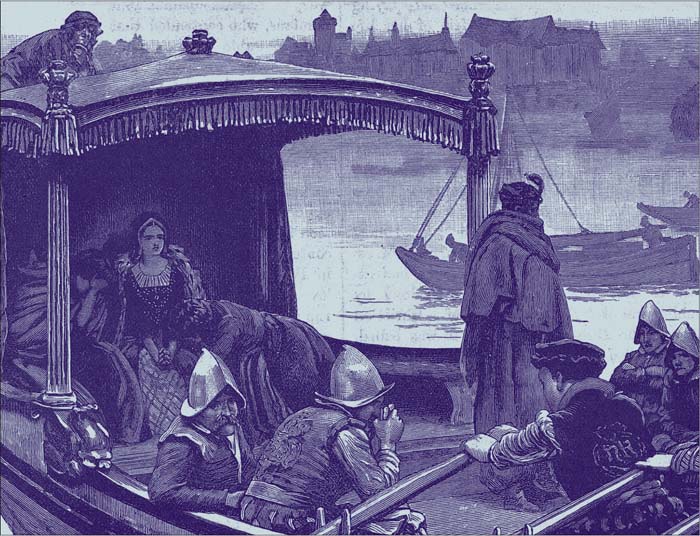

This picture shows the inside of Traitor’s Gate, one of the entrances to the Tower of London. Traitor’s Gate was close by the Thames and prisoners were rowed along the river to disembark at the bottom of the steps leading up to it.

But by now, King Henry was no longer the handsome young man he had been in his youth. He was 45, nearly 20 years older than Jane. He had grown fat and had a troublesome ulcer on his leg. His temper was worse than ever. But Jane played the submissive wife, which made Henry feel a bit better. It is likely, however, that the king’s bad health prevented Jane from conceiving quickly. It was January, 1537, before she could tell Henry she was expecting.

Henry became almost mad with joy. He was sure that the child would be a son. This time, he was right.

Jane gave birth to Prince Edward on October 12, 1547. Henry’s joy knew no bounds. Church bells pealed in celebration. Bonfires blazed. Twenty thousand rounds of ammunition were fired off at the Tower of London. Doors were decorated with garlands. Banquets were held throughout England. The party went on for 24 hours.

But something had gone wrong. Jane seemed to recover quite well from the birth. But four days later, she fell ill. It was soon clear that Jane had childbed fever. Her doctors were helpless. All they could conclude was that Jane’s servants had given her too much rich food. After three days, Jane was delirious. Another three days passed, and she was dying. She hung on for a while, but passed away on October 24.

Henry was demented with grief. He bolted to Windsor Castle and shut himself up, unwilling to see or speak to anyone. His ministers were, in any case, terrified of him. None dared come near him for some time. Particularly not with the plans they had already laid for his fourth marriage.

German artist Hans Holbein came to England in 1526 and again in 1532 to paint a series of magnificent portraits of prominent men and women, including the original version of this picture of King Henry VIII.

Henry’s ministers were practical men. With his second and third marriages, the king had failed to do his dynastic duty: to make a marriage for political advantage. Also, one infant son as heir to the Tudor throne was not enough: babies and children died all too easily and far too early in the 16th century. Henry had to marry again.

But Henry had a terrible track record. One wife hounded to death; another executed. A third, Jane Seymour, had survived mainly because she knew how to keep her mouth shut. The remnants of the Plantagenet family, and several high profile victims such as Thomas More, had all been beheaded. This King of England, it seemed, was dangerous. To marry him looked very much like a prescription for suicide.

Likely brides in Europe were thoroughly alerted. Two were daughters of King Francis I of France. He refused to let them even think of marrying Henry. Another French princess, Mary of Guise, hastily married someone else – King James V of Scotland – upon hearing that Henry had been after her. Another, Duchess Christina of Milan, agreed to marry the king – as long as she could have two heads, one for the axeman and one for herself.

It was not just the risk of disgrace and death that put these women off. Nearly 50 years old, Henry was not much of a catch. He needed a nurse, not a wife. His health was poor, his temper worse than ever. He could no longer ride or joust in the lists, once his best-loved sport. All in all, he was a wreck.

Fortunately for Henry, there was still political advantage in marrying the King of England. In Europe, small Protestant states were under threat from the prominent Roman Catholic powers, Spain and France. One such state was Cleves, in Germany. For England, the Duchy of Cleves would be a useful ally against the French and the Spaniards. The ruling Duke of Cleves, John III, had two unmarried daughters. In 1538, Duke John offered the elder, Anne, as a bride for King Henry.

Anne of Cleves was ugly, skinny and loud-mouthed. Neither was she much concerned about personal hygiene. Anne was a problem. Henry liked his wives well-covered, good-natured and retiring. He had had enough of clever women with opinions of their own. But Henry’s ministers, who approved of the match, got around this by lying to Henry about Anne. They described her as ‘moderately beautiful’. They said she was tall, but did not mention she was skinny. To back this up, they commissioned a leading artist, Hans Holbein, to paint a portrait of Anne. It showed her as a dumpy young woman with dreamy eyes, but that was not all it showed. Most of the portrait was taken up with Anne’s magnificent jewel-encrusted gown and headdress.

Jane Seymour, Henry VIII’s third queen, was quiet, demure and ill-educated – just the sort of wife he wanted. Though pale-faced and plain, Jane looks magnificent in this portrait, which emphasizes her rich robes and jeweled headdress.

Catherine Howard looks a lot older than her 15 years in this portrait, based on a painting by Holbein. Catherine managed to ruin herself within two years of her marriage and suffered the same fate – execution – as her cousin Anne.

Henry fell for it. He soon was madly in love, and demanded to meet Anne as soon as possible.

The meeting was a disaster. Anne and her entourage arrived at Deal in Kent on December 26, 1539. She set out for London at once and arrived four days later. In a tizzy of love, King Henry rushed to see her. What he beheld was not the beautiful bride he anticipated, but an absolute fright. She was badly dressed and gawky. And she smelled awful. Henry was repelled. ‘I like her not, I like her not,’ he kept repeating. Henry was enraged.

Henry summoned Thomas Cromwell, his chancellor, who had made the marital arrangements. The king habitually thrashed Cromwell, who was of low birth. Cromwell was often witnessed staggering out of meetings with Henry, his clothes awry and his hair askew. He also had at least one –more frequently two – black eyes. At their meeting to discuss Anne of Cleves, Henry was more violent than ever. But Cromwell kept his cool. He knew the alliance with Cleves was important and managed to convince the king that he was sincerely committed to this marriage. Henry, no fool, understood the significance of the alliance, too. So he gritted his teeth and married his ugly, foul-smelling bride on January 6, 1540.

But already, the king was trying to think of a way out. He had his lawyers look for loopholes in the marriage contract. The contract proved to be watertight. Next, Henry suggested that Anne was not a virgin when she married him. If she had been with other men, the marriage could have been annulled.

Henry knew perfectly well that Anne was a virgin. He kept her that way by refusing to sleep with her. Poor Anne spoke little English and knew nothing of the ‘facts of life’. She was bemused by the jokes that went around Henry’s court about the virgin bride who did not know how to do ‘it’. But Anne soon learned that she had failed to please. Her coronation as queen had been set for February 1540. Henry called it off without giving a reason.

Then Anne’s ladies-in-waiting explained to her what should happen when a husband and wife get into bed together. Anne could then hardly fail to realize that what was meant to happen was most definitely not happening. At last, it dawned on her that Henry was trying hard to get rid of her. And, as everyone knew, when Henry VIII got rid of a wife, she usually ended up in a grave.

Alarm bells began to ring loudly for Anne when Henry started paying too much attention to one of her ladies-in waiting. Catherine Howard, a cousin of Anne Boleyn, was about 15 years old, but was very beautiful and knew how to please men. She had had at least two lovers since the age of 12. Although she could not read or write, and was interested in nothing but her own pleasure, Catherine was lovely to look at, young, flirtatious and ignorant – for King Henry, Catherine Howard filled the bill perfectly.

Anne was not jealous, it seemed, but was terribly frightened. Henry began to complain that she ‘waxed wilful and stubborn with him’. Thomas Cromwell, just as scared, had to tell Anne not to antagonize the king or both of them would suffer.

Cromwell was the first to suffer. Six months after Henry married Anne, Cromwell had done nothing to get Henry off the hook. In the summer of 1540, Henry ran out of patience and set the dogs on him. On June 10, 1540, Cromwell was arrested and taken to the Tower of London. The same day, he was accused of treason and heresy. It was a trumped-up charge, of course, but having framed Cromwell, Henry pursued it to the end. On July 28, Cromwell was duly executed on Tower Hill.

Henry had already taken charge of ending his hated fourth marriage. He sent Anne to Richmond Palace, promising to join her in two days. He never showed up. Meanwhile, he pursued Catherine Howard. Every evening, the king could be seen sailing by barge along the River Thames to Lambeth, where Catherine had been given apartments.

At Richmond, Anne became more and more agitated. So it was a tremendous relief to her when, on July 6, Henry’s counsellors arrived to ask if she would agree to a divorce. Anne had feared much worse. She grabbed the divorce with both hands. Her marriage to Henry ended three days later.

Just under three weeks after his divorce from Anne, on July 28, 1540, King Henry married Catherine Howard. He thought he had achieved bliss at last, but he was wrong, mainly because he had failed to read the tell-tale signs at the start. Catherine Howard had been on the ‘good-time-girl circuit’ – always looking for wild fun and not minding how she got it. She had lost her virginity long before Henry married her and her worldliness stood her in good stead when it came to seducing the aging, sickly king.

Catherine pretended to ignore Henry’s huge bulk: he had a 54-inch waist. She also overlooked the oozing ulcer on his leg. Once, Henry had been able to dance all night and ride all day. Now, he could barely walk. Catherine paid no attention to that, either. Instead, she flattered him. She appealed to his vanity. He was hooked. He made a spectacle of himself in public, kissing and fondling her no matter who was watching. He called Catherine his ‘rose without a thorn’. He pampered her, showering her with sumptuous gifts. In 1541 he presented her with jewels – 52 diamonds, 756 pearls and 18 rubies – to say nothing of furs, velvets, brocades and other finery.

This document, dated July 9, 1540, set out the annulment of Henry’s marriage to Anne of Cleves. Henry had not been able to bring himself to consummate the marriage, but he was fond of Anne and often visited her after their union ended.

Henry loved to show Catherine off. In July 1541, he took her on a ‘progress’, or tour, though the eastern and northern counties of Britain. But Catherine was in for a shock. When the ‘progress’ reached Pontefract in Yorkshire, Francis Dereham, one of her former lovers, showed up. Dereham knew far too much about Catherine, things that she did not want King Henry to discover. When Dereham asked to be allowed to join Catherine’s household she had to agree. On August 27 Dereham became Catherine’s private secretary.

If Catherine had hoped that would satisfy him, she was mistaken. Francis Dereham was the sort of young buck who could not keep his mouth shut. Dereham began to boast that he had known Catherine before King Henry. Everybody realized what he meant by ‘known’. Sooner or later, the truth about Catherine’s past was bound to come out.

Catherine Howard was barely 17 years old when she was accused of adultery and beheaded in 1542. This 19th century illustration shows Catherine being rowed in some luxury to her imprisonment in the Tower of London.

It was sooner. In October 1541, Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, received information about Catherine’s life before marriage. The information came from Mary Lascelles, who had lived in the same household as Catherine in Norfolk. Cranmer decided to investigate. He had a heart-to-heart talk with Mary Lascelles. She told him everything.

Cranmer turned pale as Mary described Catherine’s noisy lovemaking sessions with Francis Dereham. He heard of how another lover, musician Henry Manox, boasted that he knew of a mark on Catherine’s body where no man but her husband had a right to look. When Cranmer told King Henry, he refused to believe a word of it. It was just wicked gossip, he said. But just in case, he asked Cranmer to make further investigations. Meanwhile, Henry ordered Catherine to remain in her apartments. The allegations, he was sure, would soon be disproven.

They were not. Cranmer’s new investigations backed up everything the Archbishop already knew. Henry was devastated. He sat on his throne in the Council chamber and wept openly. He shut himself away in his palace at Oatlands in Surrey. He was eaten away with grief for his shattered happiness.

When Catherine was charged with ‘misconduct’, she became hysterical. She wept and wailed and threw herself about so violently that her attendants feared she was going to kill herself. When she calmed down, Catherine knew she had only one hope: she would have to beg Henry to forgive her.

Catherine waited until Henry passed close by her apartments on his way to prayers. She dashed past her guards and ran towards the king. But she was unable get near him. The guards grabbed her before she could speak to him. Catherine was taken back to her apartments, screaming and struggling. She never saw Henry again.

This elegant portrait features Henry’s sixth and last wife, Catherine Parr, who married the king in 1543. It is based on a painting by Hans Holbein, who died during an epidemic of bubonic plague in London the same year.

Now Catherine and her lovers were quizzed relentlessly for evidence. Cranmer did not get much information out of Catherine. Whenever he tried to question her, she wept and became hysterical. However, she did mention another man she had known before marriage – Thomas Culpepper, now at Henry’s court as a gentleman of the King’s Privy Chamber. Culpepper was immediately arrested. His rooms were searched and a love letter from Catherine was found.

Cranmer was now hot on the trail. When he questioned Lady Rochford, one of Catherine’s attendants, she told him everything about the love affair between Catherine and Culpepper. Lady Rochford disclosed how she had stood guard outside the bedroom door while the pair made love at Pontefract and elsewhere. Having sex before marriage was bad enough. But love-making at Pontefract meant that Catherine had committed adultery. And for that, there was only one penalty: death.

On December 10, 1541, Thomas Culpepper and Francis Dereham were executed. Afterwards, their heads were stuck atop pikes on London Bridge. The queen was executed two months later.

At long last, King Henry had learned his lesson. He would never find happiness by marrying young girls. The next time he chose a wife, in 1543, he chose well. Catherine Parr was a mature woman who had had two previous husbands. Thirty-one years old, she was more than 20 years younger than Henry. But she was level-headed, pleasant and kind-hearted. Henry married for the sixth and last time on July 12, 1543. During the next four years, Catherine Parr made a happy home for him and his three children. This was something none of them had ever known before.

But four years were all they would have. By the end of 1546, King Henry was in a worse state than ever. He found it difficult to walk. He had to be winched up and down stairs by a mechanical hoist. He was dying.

Catherine stayed with him as he lay on his deathbed. So did his daughter by Catherine of Aragon, Princess Mary. But both became so upset that Henry told them to go away. For Catherine, it was a good thing. Before King Henry died on January 28, 1547, it was not her name that he cried out as he lay dying. Instead, he called for Jane Seymour, whom he had loved and lost ten years before. After his death, Henry was buried next to Jane at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor.

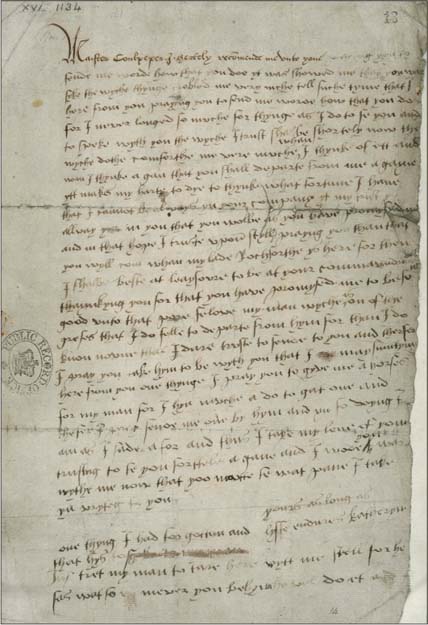

This letter from Catherine Howard to Thomas Culpepper – probably dictated since she was almost illiterate – was open and affectionate, and became a vital piece of evidence against her when she was accused of adultery.

This painting illustrates the scene at the execution of the unfortunate Lady Jane Grey, a victim of the plot that surrounded the succession to the English throne in 1553.