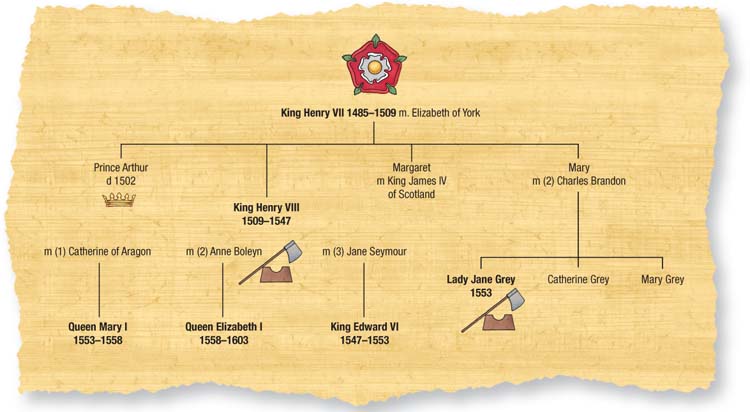

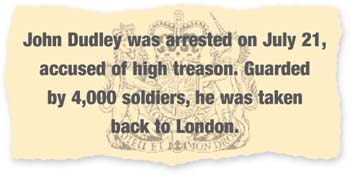

The new king, Edward VI, was a boy of nine. His heirs were his half-sisters, Mary, daughter of Catherine of Aragon, aged 31, and Elizabeth, aged 13, daughter of Anne Boleyn.

![]()

This was just the situation King Henry VIII had wanted to avoid. He had destroyed two wives in his search for a son to succeed him. Now, the Tudor throne was in the hands of a boy, a woman and a girl. And though it was not yet apparent, the last two had been badly affected by the turmoil of Henry’s first two marriages.

Princess Mary had once been a bright, beautiful child, adored by her father. But she had suffered badly during her father’s battle with her mother, Catherine of Aragon. Mary, aged 31 when Henry died, was left mentally scarred. Deprived of love, she craved it badly. Roman Catholicism was outlawed in England by this time. But Mary remained a devout Catholic just the same. It all led to terrible mistakes and a sad, lonely end.

Princess Elizabeth could have gone the same way. But years of turmoil had hardened rather than weakened her. She was unusually shrewd, even at 13. She was also very wary. She had been less than three years old when her father killed her mother. When Elizabeth was only eight, there was another execution: Catherine Howard, who had befriended Elizabeth, had her head chopped off. After that, Elizabeth came to believe that marriage was dangerous. Men were dangerous. These fears were to affect Elizabeth for the rest of her life.

Another Tudor family portrait by Holbein, this time of Edward VI, who succeeded his father, Henry VIII, in 1547. There was something wrong with the Tudor line – Edward was the third Tudor boy to die young, at just 15.

King Edward VI also had a problem: he was too young to rule on his own. He had to have a protector. This was the cue for two very ambitious men to seize the power they had always wanted: the boy-king’s uncles, Edward and Thomas Seymour.

Edward Seymour was a fast mover. Two days after the death of King Henry VIII, he filled the Royal Council with his cronies. Then, with their help, he had himself proclaimed the boy-king’s Protector. Next, Seymour gave himself a grand title – Duke of Somerset.

Meanwhile, Seymour’s younger brother, Thomas, was plotting his own way to power. He planned to get it by the back door: if he could marry into the royal family, he would gain riches and a say in government.

There were three ways Thomas Seymour could ally himself to the royal family – he could marry Princess Mary, Princess Elizabeth or Henry VIII’s widow, Catherine Parr. Mary and Elizabeth turned him down flat. They were princesses. Marriage to an upstart like Thomas Seymour would have been beneath their royal dignity. So Thomas fell back on Catherine Parr, who had in fact been betrothed to him before she married King Henry. Now he charmed her again. They married in secret in May, 1547. Thomas Seymour had reached first base.

Not that his marriage stopped him from playing around. Seymour was particularly keen on Elizabeth. Seymour often went to her bedroom, wearing scanty clothes. He played suggestive games with Elizabeth. Seymour did not attempt to hide his activities. At court, he paid Elizabeth so much attention that Catherine, who was pregnant, became jealous.

The unfortunate Catherine died in childbirth on September 5, 1548. This robbed Thomas Seymour of his precious royal connection. He became desperate. One night in January 1549, he was found outside King Edward’s bedroom. He held a smoking pistol in his hand. The young king’s pet dog lay dead at his feet. The only explanation offered was that Thomas had meant to kill the king.

Protector Edward Seymour had never trusted his scheming brother. This was a chance to get rid of him. Thomas was accused of treason, and on his brother’s orders, was executed on March 20, 1549.

But Edward Seymour had himself made many enemies. He was hated for the way he grabbed power in 1547. The most deadly of his enemies was John Dudley, Earl of Warwick. Dudley was a cool customer. He was cunning, clever and much more ruthless than Edward Seymour. He had been planning the Protector’s downfall for some time. On October 6, 1549, he struck.

Dudley arrived with a small armed force at Hampton Court Palace, near the River Thames. King Edward and Seymour were there at the time. The Protector hustled the boy-king onto a barge and ordered the bargemen to row downriver for Windsor – fast. Edward got there safely. But Seymour knew the writing was on the wall. Eight days later, he gave himself up and was sent to the Tower of London.

Subsequently, Seymour was charged with embezzlement and unlawful seizure of power. He was fined, and sacked from his role as Protector. He was released, and Dudley allowed Seymour to live a while longer, safe in the knowledge that sooner or later the former Protector would slip up. Then he could be accused of more serious crimes – crimes that carried the death penalty.

John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, plotted to supplant Princess Mary, the rightful heir to the throne. His scheming ended in disaster and death for himself, his son Guildford Dudley and Dudley’s wife Lady Jane Grey: all of them were executed.

Seymour gave Dudley the chance he wanted in 1552. The Catholic Princess Mary had refused to have anything to do with Protestant church services. The Royal Council tried to bully her, but she would not give in.

Unfortunately for Edward Seymour, he had a fondness for Mary and supported her. With that, John Dudley pounced. He accused Seymour of wanting to restore the Roman Catholic Church in England. To back that up, Seymour was also charged with conspiring against the Royal Council.

It was a lethal package. Seymour was found guilty and sentenced to death. King Edward was horrified. He begged Dudley to spare Seymour’s life. Dudley ignored his pleas and Edward Seymour was executed on January 22, 1552.

With both the Seymour brothers dead, John Dudley had a free hand to do as he pleased. He gave himself and his supporters grand titles. He became Duke of Northumberland. Dudley and his cronies plundered the monasteries and university libraries of their treasures. They grabbed royal estates worth a phenomenal £30,000 a year. By the time they had finished, England was almost bankrupt.

Meanwhile King Edward, now 14, was feeling the strain. The Seymour brothers had pressured him and torn his loyalties back and forth. But John Dudley was much worse. He was a pure brute. He treated the boy-king like a puppet, bullying him mercilessly. He nagged him to sign documents and laws. Edward had no say in anything: Dudley was all powerful.

Then, at the end of January 1553, Edward became seriously ill. He had a high fever, his lungs were congested, he could barely breathe. When Princess Mary came to visit him, he failed to recognize her. Edward, aged 15, was clearly dying. Alarm bells rang for John Dudley. If Edward died, Catholic Mary would become reigning queen. That would be the end of Dudley’s power. He had no intention of letting that happen.

The plot he laid to hang on to power was truly dastardly. Dudley arranged three marriages. Sisters Lady Jane Grey, Catherine and Mary were members of the Tudor royal family, descended from Henry VIII’s sister Mary. Jane Grey was considered most important of the three. Dudley married her off to his own son, Guildford Dudley. Catherine and Mary married powerful nobles, both Dudley’s allies. That done, Dudley went to King Edward and bullied him into agreeing that if Princess Mary became Queen it would be a disaster for England. Poor Edward was too ill to resist. On Dudley’s orders, the young king changed the succession to the throne. Now, his successor was to be Lady Jane Grey.

Jane Seymour’s brother Edward made himself Protector to her son, King Edward VI, but was outmaneuvered by the more brutal and ambitious John Dudley. Accused of treason, Edward Seymour was sent to the Tower and executed in 1552.

But Dudley had not finished with Edward. The boy was now a ghastly figure. He looked like a skeleton. His lungs had been eroded by tuberculosis. There were running sores all over his body. Dudley decided that he had to be kept alive. He called in a quack doctor who dosed Edward with arsenic. This drastic treatment revived the boy for a time. It was just long enough, Dudley thought, to trap Mary and Elizabeth. He invited both to Greenwich, in London, to see their dying half-brother.

Elizabeth immediately suspected a trap and refused to come. She guessed, correctly, that Dudley meant to imprison her and Mary. Mary was not quite so astute. She set out for London. But when she reached Hoddesdon, 25 miles (40km) from the capital, she received a warning that Dudley was up to no good. Mary fled to Kenninghall, her house in Norfolk. It was a much safer 85 miles (136km) from London.

The escape of Elizabeth and Mary foiled Dudley’s plan. But there was nothing he could do about it. Late in the evening of July 6, 1553, Edward VI died. At the end, he had been too weak to speak, or even cough.

The order for the execution of Lady Jane Grey that took place in 1554. Queen Mary shrank from executing her after the failure of Northumberland’s plot, but the rebellion against Mary’s planned marriage to Philip of Spain meant Jane had to die.

John Dudley was in a fix. In Norfolk, nobles rushed to support Princess Mary, escorted by their armies. Soon, Mary’s forces numbered 30,000 men. On July 9, Dudley had Lady Jane Grey declared Queen. But Mary’s support kept growing.

Mary was now safeguarded in the fortress at Framlingham. Dudley set out from London to capture her. With Dudley gone, his supporters became so frightened they shut themselves up in the Tower of London. Lady Jane Grey and her husband were among them.

On his march to Framlingham, things went from bad to worse for Dudley. His troops started to desert. He heard that Londoners had declared their support for Mary. He himself was branded a rebel and realized his plan was hopeless. Overnight, his power had vanished. Dudley became hysterical. He tossed his cap into the air and shouted: ‘Long live Queen Mary!’ Tears ran down his cheeks as he said it. Against the odds, Mary was queen, the first reigning queen England had known.

John Dudley was arrested on July 21, accused of high treason. Guarded by 4,000 soldiers, he was taken back to London. The people of England had come to hate Dudley. All the way, people lined his route to the capital. They jeered at him. They cursed him. They threw stones, shook their fists, shouted insults. When he reached London, he was imprisoned in the Tower.

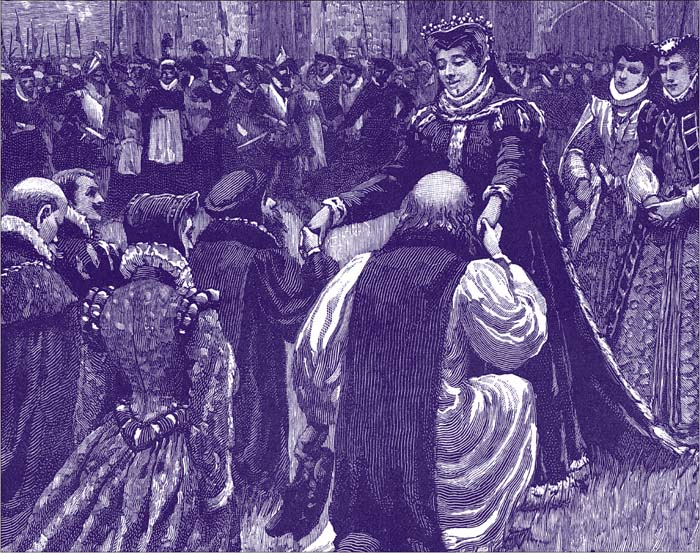

Meanwhile, on August 3, Queen Mary entered London. It was a triumph all the way. Huge crowds gathered to cheer her. Some were so happy they wept. The noise was deafening. No monarch of England had ever received such a greeting.

Although she has since acquired the nickname ‘Bloody Mary’, Mary I was a kind woman who began as England’s first ever reigning queen with an act of mercy: she pardoned five prisoners incarcerated in the Tower of London.

Mary dressed for the occasion. Her gown was of royal purple. Her neck was circled with jewels. Even her horse had trappings made of cloth of gold. But she was now 37 and looked even older. All her sufferings now showed on her lined, pale face. Mary was not a cruel woman. She tried to see good in everyone. She was remarkably forgiving. But she could not forget what she had endured during the reigns of her father and brother.

As the cheering Londoners would soon learn, Mary’s reign would be payback time for those sufferings. Her subjects would suffer in turn.

But all that lay in the future. On August 3, 1553, Queen Mary was on a high. And it was typical of her to begin her reign with an act of mercy. She pardoned five prisoners from the Tower of London. Mary’s ministers expected her to punish the conspirators who had tried to cheat her of her throne. Mary confounded their expectations by pardoning all but three. Only John Dudley and two cronies were executed, on August 22, 1553.

But what to do with Lady Jane Grey, who had been ‘queen’ for only nine days? What about her husband, Guildford Dudley? People expected that they, too, would soon lose their heads. But Mary would not execute them, though they did remain imprisoned in the Tower.

Mary’s primary aim was to restore England to the Roman Catholic Church. Unfortunately, she did not understand that her subjects were solidly Protestant. They wanted nothing to do with Catholics or with the Pope. With this, the stage was set for a major clash between the queen and her people. It became even bigger when news leaked out of Mary’s marriage plans. Mary had chosen Philip, the son of King Charles of Spain – a Catholic, and a foreigner.

Mary was not as free to choose her own husband as she thought. Reaction against the ‘Spanish Marriage’, as it was called, was violent. Parliament was against it. Mary’s ministers were opposed. Protestant bishops of the English church disapproved. Most of all, the people were against it. But foolishly, Queen Mary ignored them all. On October 29, 1553, she announced that she was betrothed to Philip. She would ‘never change,’ she said, ‘but love him perfectly…’

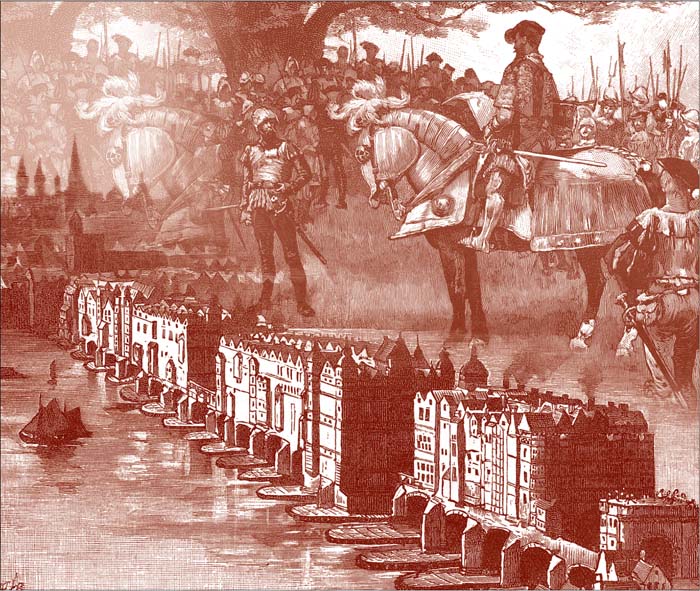

Wyatt’s rebellion, which protested against the planned marriage of Queen Mary and Philip of Spain, was a terrifying experience for Londoners. Wyatt’s army was massing, ready to march on the beleaguered city.

A wave of alarm spread through England. There were fearful stories doing the rounds that a Spanish army 8,000 strong was en route to England. The Spaniards sought to take over the Tower of London, ships of the English Navy and England’s ports.

None of these stories were true, of course. But rebellions were being planned all over the country. The rebels’ leader, Sir Thomas Wyatt, was ready to march on London. Once there, Wyatt planned to use his military might to force Queen Mary to put a stop to the Spanish Marriage.

Wyatt and his followers set out for the capital on January 25, 1554. There was panic in London. Watchers were posted at every gate into the city. Mary ordered the bridges over the River Thames destroyed. Soldiers guarded the streets. Lawyers, priests and tradesmen wore shirts of mail beneath their robes for protection.

About the only one who did not panic was Queen Mary herself. She refused to leave London. She told Londoners: ‘Good subjects, pluck up your hearts and like true men, stand fast against. . . our enemies and yours, and fear them not, for I assure you I fear them nothing at all!’

That cheered up Londoners for a while. But panic soon returned. The bridges had been destroyed, as Mary had ordered. But on the night of February 6, Thomas Wyatt swam across the icy River Thames. He found a boat and used it as a floating platform to repair one of the bridges.

That done, some 7,000 rebels marched across and on to London once again. On February 17, they reached the gates of the city. There, waiting for them, stood 10,000 soldiers, 1,500 cavalry and row upon row of heavy cannon.

As the rebels advanced, the lines of soldiers parted. Wyatt rushed through with his vanguard of about 400 men. But it was a trap. The soldiers closed in behind him. Now Wyatt had to fight it out in the streets of London with only a small force to help him. At first, he met no resistance. But when he reached Charing Cross, he came up against a force of the Queen’s Guards. But they did not fight. They ran for safety to the nearby Palace of Whitehall. Wyatt and his force followed. They peppered the windows of the palace with arrows.

Queen Mary, inside, heard the noise. One of her senior commanders, Edward Courtenay, was quivering with fear.

‘Well then, fall to prayer’, the queen told him scornfully. ‘And I warrant you, we shall hear better news anon.’

Better news soon arrived. A troop of Mary’s cavalry attacked Wyatt and his followers. Before long, Wyatt’s men were cut down. The streets were stained with their blood. At last, with only a handful of men left standing, Thomas Wyatt surrendered.

Despite her bravery, Mary had been badly shaken by Wyatt’s rebellion. She realized that she could no longer afford to be merciful. There would be no pardon for the rebels this time. Nearly 200 were condemned to death. Forty-six were hanged in London in a single day. Lady Jane Grey and Guildford Dudley were executed soon thereafter.

The unfortunate Lady Jane had had to die, but she was an innocent victim. The same could not be said of Princess Elizabeth, Queen Mary’s half-sister. At least, Mary did not think so. What made Mary suspicious was the way Elizabeth avoided contact with her. She would not come to court. She would not attend Catholic Mass. Mary was sure Elizabeth had conspired with Thomas Wyatt and the rebels.

Today, the Tower of London is no longer a place of terror and death. It is one of London’s most popular tourist attractions: the spot where the scaffold once stood is marked out for visitors to see the place where so many people were beheaded.

Then, on March 17, 1554, Elizabeth was arrested and taken to the Tower of London. But she denied knowing anything about Wyatt’s rebellion. There was no real evidence against her. After two months, she was released, and taken under guard by barge to Woodstock in Oxfordshire.

Queen Mary I was an attractive young woman before frustration, disappointment and a failed marriage embittered her and aged her before her time. She was particularly fond of jewels, fine brocaded fabrics and delicate lace ruffs and collars.

Queen Mary was alarmed to see how popular Elizabeth was. All the way, people lined the banks of the river. They cheered her loudly. Church bells rang out. Guns were fired in celebration. Women baked special cakes for Elizabeth. Before long, her barge was piled high with gifts.

Meanwhile, the leaders of Wyatt’s rebellion were heavily punished. One of them, the Duke of Suffolk, was beheaded on February 23. Wyatt himself was hung, drawn and quartered.

Members of Parliament had protested violently against the Spanish Marriage. But the day Wyatt died, they gave in. The Royal Marriage Bill became law. Gritting their teeth in fury, Parliament told Mary that Philip would be welcome in England.

But Philip was not too happy about the marriage, either. The last thing he wanted was to marry a scrawny, aging queen eleven years older than he. But he had to go along because his father, King Charles, wanted to ally Spain with England. That way, Charles could get his hands on English money and troops for his war with France.

Mary knew nothing of all this. She imagined her marriage was going to be a great romance. She longed to be loved. She looked forward to showing off her handsome young husband. Philip, Mary thought, had been given to her by God. Poor Mary. It was all a dream.

A devout Catholic, Queen Mary I longed to return the English church to the jurisdiction of the Pope in Rome, and during her reign some 300 Protestants were burned at the stake for resisting her demands.

Philip left Spain for England on May 4. He took his time getting there. It was not until July 21 that he met Mary for the first time. It was not a happy meeting. Philip found Mary repulsive and could not stand being near her. But he endured it and didn’t let his real feelings show.

Philip and Mary were married in Winchester Cathedral on July 25, 1554. Within days, Mary became pregnant – or at least she thought so. Great preparations were made for the birth. A religious service was held to give thanks for the queen’s quickening, the moment when her baby showed its first signs of life. Mary sat there, proud and happy. She let her swelling belly show, so that ‘all men might see she was with child’.

Philip of Spain was eleven years younger than Queen Mary when, very reluctantly, he agreed to make a political marriage with her. Later, as King Philip II, he became the sworn enemy of Mary’s Protestant half-sister, Queen Elizabeth I.

But Mary’s plans to return England to the Catholic faith were not going well. There was a lot of resistance, so much that Mary resorted to burning the resisters in public. That was a mistake. The watching crowd howled with anger. Each burning inspired more ugly scenes than the last. Hatred for Queen Mary increased. Now, she had a new name – ‘Bloody Mary’.

Philip tried to put a stop to the burnings. Unlike Mary, he realized the more people she burned, the more she was hated. Even for his sake, however, she would not stop. The burnings went on.

But a terrible humiliation awaited her. The birth of her baby had been expected on or near May 23, 1555. But the date passed and there was no sign of a baby. There had been nothing by the end of June. There were suggestions that the Queen was not pregnant at all, that she had imagined the whole thing.

At first, Mary refused to believe it. But months passed. Still nothing happened. In the end, Mary had to admit she had been wrong. There was no baby. She became deeply depressed. At this point, just when she needed him most, Philip decided to leave England. Mary begged him not to go. But Philip had had enough of England, the English and their queen. On August 22, 1555, he left for his own territory, the Spanish Netherlands. Mary wept bitterly as she watched him leave.

Soon, gossip reached England that Philip was having a great time in the Netherlands. He was going to parties, attending weddings and dancing until dawn. He was also playing around with other women – all in all, acting as if he had been freed from prison. No one dared tell Mary what was going on. But that was not all they dared not tell her. Mary’s doctors had now discovered the truth of her ‘pregnancy’: she had a tumor in her womb.

Philip kept promising Mary that he would soon return to England. But he had no intention of returning. Mary became more and more depressed. She could not perform her duties as queen. She shut herself away and mourned for Philip as if he were dead.

Time passed, and Philip showed no signs of coming back. Then, in 1556, his father, King Charles, gave up the throne of Spain. Philip was now king in his own right, King Philip II of Spain and of its huge, rich empire in America.

To defend his vast territories, Philip needed money. And for money, he needed England. Philip returned at last in 1557. Mary greeted him with joy. But joy soon faded. Once Philip had the money, troops and ships he needed, he was gone. Mary never saw him again. All she had for comfort was the belief that she was pregnant again. But it was another phantom pregnancy. Philip had not gone near his wife while he was in England. The truth was that Mary’s tumor had returned.

By November 1558, Mary was dying. For hours, she lay in a coma. When she spoke, she talked of seeing little children in her dreams. A priest came to give her last rites. While he was saying the prayers, she died.

When news got out that hated ‘Bloody Mary’ was dead, people all over England celebrated. They sang and danced in the streets. They rang bells. For many years thereafter, the day Mary died, November 17, was celebrated in England as a public holiday.

Elizabeth I’s richly embroidered robes and magnificent jewels disguised the weakness of her realm and made her look more powerful.