Queen Elizabeth I lived longer than any other Tudor monarch. She lost her hair and her teeth, but she kept her guts. In 1601, when she was 67, her beloved Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex, rebelled against her.

![]()

She was furious…so furious that she declared she would step out onto the streets of London to see if any rebels dared to shoot her. Her ministers barely prevented her from doing it.

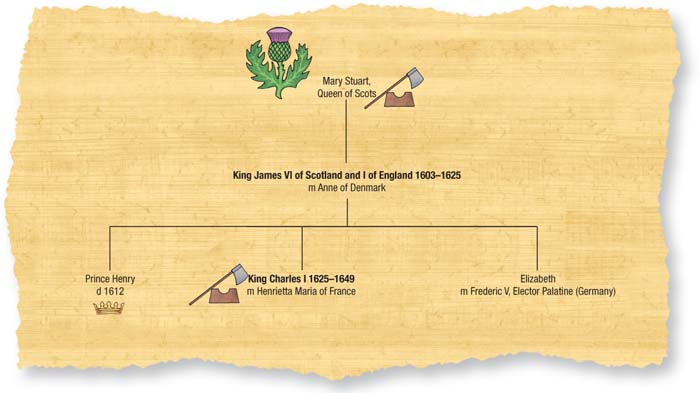

But by late in 1602, Elizabeth was not well. She refused to eat. She would not take any medicines. She even refused to go to bed. She thought if she went to bed, she would die. There was not long to go until the end. Elizabeth died sitting in a chair on March 24, 1603, the last of the Tudor monarchs. It was only at the very last moment that she named her heir – King James VI of Scotland. In a historic event which united the monarchies of England and Scotland, he then became James I of England, first of the Stuart kings.

James set out for London in May 1603. He was so eager to get there that he rode 40 miles in less than four hours. That was fast going for the time, but too fast. On the way to London, James fell off his horse, injuring himself. His doctors thought he had broken his collarbone.

When James reached London at last, he received a great welcome. Thousands turned out to see their new king enter the city. Celebrations went on far into the night. But the excitement soon wore off when the public discovered its new monarch not only looked weird, but that his personal tastes and habits were truly repugnant.

King James soon found, however, that he was in a nowin situation. After their disappointment, a group of Catholics led by Guy Fawkes hatched the famous Gunpowder Plot of 1605. It was very ambitious, involving nothing less than blowing up the Houses of Parliament when King James and his ministers were in attendance.

The plot never got going. Guy Fawkes was discovered red-handed in the cellars of the Houses of Parliament, together with his stock of gunpowder. The plotters were hung, drawn and quartered as traitors. Ever since, Guy Fawkes Day has been celebrated in England on November 5. Dummy models of Fawkes are displayed in the street. Children ask passersby to give them ‘a penny for the Guy’. Fireworks displays take place all over England.

James believed in witchcraft. There had been a Witchcraft Act in Queen Elizabeth’s time. But that was not enough for James. He changed the act to include cannibalism among the dark practices performed by witches.

‘If any person or persons shall use, practice or exercise any invocation or conjuration of any evil or wicked spirit…or take any dead man or child out of his or her grave, or the skin, bone or any part of any dead person, to be employed or used in any manners of witchcraft…they shall suffer the pains of death.’

Guy Fawkes was caught red-handed with several barrels of gunpowder and was arrested on the spot. Though not the leader of the Gunpowder Plot, he has since become the focus of its commemoration in England on November 5 each year.

Though he was married and had children, James was also homosexual. He used to prowl around his court looking for beautiful young males as lovers. When James took a fancy to one, the king would plant sloppy wet kisses on his cheeks. He would fondle him in full view of the court.

One who received this royal treatment was handsome George Villiers, who became Duke of Buckingham. Villiers was canny enough to know that being the king’s lover was more than just a guarantee of a grand title. It could lead to wealth and power as well. James adored Buckingham. He pawed and petted him in public. He called him his ‘sweet Steenie’. In letters to him, King James addressed Buckingham as ‘sweetheart’. When Buckingham went abroad on a foreign mission, James wrote to him, saying: ‘I wear Steenie’s picture on a blue ribbon under my waistcoat, next to my heart.’

But the king’s advances were not always welcomed. The Earl of Holland, for example, turned aside and spat after James had ‘sladdered’ in his mouth. James’s courtiers, looking on, were disgusted. A later historian, Thomas Babington Macaulay, called King James ‘a nervous drivelling idiot’. He was not far wrong.

The English could just about put up with all this. After all, they had had some peculiar kings before and England had survived. What they could not stand, however, was a highly dangerous notion James had brought with him from Scotland. This was the Divine Right of Kings, which belief implied that James had been appointed as king by God. Only God could judge what he did. James considered himself above the law and told Parliament so in 1610:

‘The state of monarchy’, said James, ‘is the supremest thing on earth. As to dispute what God may do is blasphemy…so it is seditious in subjects to dispute what a king may do…. ’ He went on: ‘Kings are not only God’s lieutenants upon earth and sit upon God’s throne, but even by God himself they are called gods.’

This was alarming rhetoric. English kings had never before been allowed to carry on in such a way. Parliament and its predecessors, the English barons, had fought a long battle for the right to advise the monarch. Now here was King James telling Parliament that they could ‘go to hell’: he chose his ‘sweet Steenie’, the Duke of Buckingham, as his one and only adviser.

James also found a way around Parliament’s chief power: their right to grant the king money. James obtained funds in other ways: he imposed taxes on imported goods, forced the aristocracy to accept loans, and sold offices to the highest bidder. All of this was illegal.

Parliament fumed. But they settled down to wait: sooner or later the king would run out of cash. When he did so, Parliament had the chance to hit back. The king spent money like water. His coronation had cost £20,000. His wife, Queen Anne, went overboard with expensive clothes and jewels. James gave cash away in handfuls to courtiers. Entertainments at his court were always lavish. The most popular, the masque, cost a fortune. Many such masques were staged at the court of King James.

Eventually, in 1621, James needed money so badly that he was forced to call a Parliament. The members got their shots in first. For a long time they had been angered by the partiality James showed to Roman Catholics. They wanted England to be Protestant through and through. Above all, they wanted an end to James’s friendship with Catholic Spain. Their demands, in the form of a ‘Protestation’, were entered into Parliament’s journal. James was furious. He sent for the journal. He tore out the pages where the Protestation was printed. Parliament knew what they could do with their Protestation.

King James I of England was also King James VI of Scotland. This illustration shows him dressed in state robes, holding the orb and sceptre that were part of the Crown Jewels and the regalia that signified his royal powers.

Charles I looks very dandified in this portrait, wearing a long wig and broad-brimmed hat. The horse was posed with its head down, with its groom leaning to one side, to conceal the fact that the king was only 4 feet 7 inches tall.

Then, quite suddenly, King James gave in. In 1624 he let Parliament have everything they had ever wanted. A say in foreign policy; an end to preference toward Catholics – even the right to make war.

‘If I take a resolution, upon your advice, to enter into a war,’ James told Parliament, ‘then yourselves…shall have the disposing of the money. I will not meddle with it.’

Parliament, triumphant at last, voted the king the enormous sum of £30,000. James’s turnaround had been amazing. But there were good reasons for it. He was only 57, but getting old. He had suffered a stroke. He was becoming senile and did not have long to live. Letting Parliament have what it wanted was the only way to get a quiet life. James died on March 27, 1625 at his country home, Theobalds in Hertfordshire.

Thirteen years earlier, James’s heir, Prince Henry, had died of typhoid fever. This was not only a tragic loss for his parents, but for England as well.

Henry, only 18, had been a bright young man. He had up-to-date ideas about working with, instead of against, Parliament. He was a devout Protestant. When Henry came to the throne, so it was said, all the problems his father had caused would be cured. But it was not to be.

What England got instead of Henry was a new version of King James. King Charles I, James’s second son, was a very small man, four feet seven inches tall. He was stubborn, shy, slow and stupid. All his life, he stammered. Worse, he took over the Duke of Buckingham as his own lover. Worse still, Charles was another ‘Divine Right of Kings’ adherent. Parliament cringed when Charles said: ‘I must avow that I owe the account of my actions to God alone’. It might have been his father James talking.

There were all sorts of bad omens on February 2, 1626, the day Charles was crowned king. One of the wings on the dove topping Charles’ sceptre broke off. A jewel popped out of the coronation ring. Most frightening of all, there was an earthquake. Superstitious people began speculating that there would be trouble ahead.

There certainly was trouble ahead. In the reign of James I, Parliament had argued fiercely with him. But they had always been loyal to him as king. Charles’ Parliament was different. It was full of extreme Protestant Puritans. They were not willing to put up with King Charles – or any king. To them, all kings were tyrants.

This placed Charles in a very dangerous position. He made it worse by employing all his father’s tricks. He imposed taxes on his people – some illegal. He clung to Buckingham, who practically controlled the king and so controlled England.

The duke was widely hated. Slanderous ditties were written about him. Rude ballads were sung. Seditious pamphlets were written. Then, on June 28, 1628, a mob gathered in London for a ‘we-hate-the-Duke’ meeting. Nearby was a playhouse where a performance had just ended. Someone spotted John Lambe, the duke’s doctor, coming out one of the doors. The mob howled. Lambe ran. He darted from one tavern to another, desperately seeking shelter. But the mob caught up with him. They seized Lambe and beat him to death on the pavement.

Murdering the duke’s doctor was the next best thing to killing the duke himself. But it wasn’t good enough for one John Felton, who had a personal grudge against Buckingham.

The Duke of Buckingham was murdered by a man, John Felton, who had a personal grudge against him. Felton became a hero: the death of Buckingham was welcome to many people who disliked his influence over King Charles.

In 1627 Buckingham had refused to make Felton a captain in the Navy – and had been very insulting about it, too. Felton vowed revenge. On August 23, 1628, Felton waited for Buckingham outside the Greyhound Inn in Portsmouth. Buckingham had just finished breakfast when Felton rushed up and stabbed him in the chest. That one blow was enough. Buckingham fell to the ground dying.

John Felton was hanged for his crime, but he became a national hero. Londoners cheered and celebrated when they heard Buckingham was dead. Parliament was pleased, for they had wanted to get rid of Buckingham for years. Now he was gone, and King Charles was on his own.

By now his disputes with Parliament had reached new heights. They were on a collision course. Inside Parliament, on March 2, 1629, Charles’ supporters and opponents actually brawled in the House of Commons chamber.

Charles soon put a stop to that. He dismissed Parliament and ruled without it for eleven years. He kept his cash flow going in the same way as had King James. A tax called ‘Ship Money’ became the most hated of his fundraising schemes. Ship Money was supposed to be a tax paid by coastal towns for building ships in times of national danger. There was no national danger when Charles demanded the tax. Furthermore, he demanded Ship Money from inland towns.

Ship Money was not sufficient, however. In 1640 Charles needed £300,000 for a war against the rebellious Scots. He summoned Parliament. Nothing had changed. All the old quarrels were still there: the king must stop imposing taxes, he must be tougher on Catholics, his ministers must be controlled by Parliament. King Charles refused to give in. Instead, he dissolved Parliament once again.

Ship Money and other taxes went on. Hatred of the king increased, and Parliament lost patience. On November 23, 1641, the Grand Remonstrance was passed by the House of Commons by a margin of 159 votes to 148.

The Remonstrance was the work of John Pym and four other members of Parliament. It contained a list of the many ways in which King Charles had abused his power. Nearly six weeks later, on January 4, 1642, King Charles went in person to the House of Commons. He took a strong guard of soldiers with him. His intention was to arrest the five authors of the Grand Remonstrance. They would then be charged with treason.

Charles told the Speaker of the House of Commons, William Lenthall:

‘By your leave, Mister Speaker, I must borrow your chair a little.’

The Speaker’s chair was on a raised dais. The king stepped up on it and scanned the faces in front of him. John Pym and his four friends were not there. They had been warned not to go to the Commons that day.

Charles asked Lenthall where they were. Lenthall replied: ‘May it please Your Majesty, but as the House is pleased to direct me, whose servant I am here.’ In other words, Lenthall intended to give nothing away.

In 1642, King Charles I went to the Houses of Parliament to arrest five members who had accused him of abusing his royal powers. This began a tradition in which the British monarch is not permitted to enter the House of Commons.

The king knew he had lost. ‘Well,’ he said,’ since I see all the birds are flown, I do expect from you that you shall send them unto me as soon as they return hither.’ Then he left. John Pym and others returned a week later, but no one was about to hand them over to King Charles.

Civil war looked certain now. King Charles, his queen, Henrietta Maria, and their children fled from London to Hampton Court Palace in Surrey, where it was safer. England’s third and last civil war began on August 22, 1642. That day, King Charles ‘raised the royal standard’ in Nottingham. Now it was his supporters, the Royalists, against Parliament, the Roundheads.

The war began well for King Charles and the Royalists. They won the first big battle, at Edgehill, in Warwickshire. But after that, it seemed neither side could finally defeat the other. Too many battles ended as draws. Sieges dragged on and on.

Families took sides in the civil war. Some members supported the king, others Parliament. Many had no choice. Royalists and Parliamentarians both introduced conscription: young men were forcibly hauled off to fight. In 1643, one of the Parliamentary leaders, Oliver Cromwell, recruited a troop of women. They were known as ‘the Maiden Troops’. Their job was to ‘stir up the youth’ to fight for Parliament.

Many of the troops did not want to go to war. A group of them attacked one recruiting officer, Lieutenant Eures, in a tavern. They forced Eures to crawl out on a beam attached to the tavern sign. He was beaten. Stones were thrown at him. Then he was flung onto a heap of rubbish. But he was not dead – not yet anyway. He managed to stagger out, but his attackers spotted him and beat him savagely about the head until he died.

A royalist stronghold under assault during the English Civil War, showing one woman deafened by the artillery barrage. Civil wars are often regarded as the most savage of all: this one brought terror to thousands of ordinary people.

Cromwell was a country gentleman and farmer. He came from the same family as Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s doomed minister. He had fought in the civil war from the beginning. He soon recognized important facts about the Parliamentary army. It was untrained. It was undisciplined. Parliament was not going to win this war with an army like that.

In 1645, Cromwell set about creating a New Model Army. This was much more professional. They trained hard, lived hard, fought hard. All this made an enormous difference. On June 14, 1645, the New Model Army won the battle of Naseby in Northamptonshire. This was the beginning of the end for King Charles. He fled for safety to Hereford. But he knew his cause was lost.

Charles cut his hair short. He put on a false beard. Then, disguised as a servant, he went north, to Scotland. There he gave himself up. As King of Scotland as well as King of England, Charles hoped the Scots would help him. But the Scots Presbyterians had no intention of doing so, unless Charles agreed to their terms. They wanted him to impose their Presbyterian faith in England, but for Charles this was anathema: Presbyterians believed that kings should be accountable to the people, who held supreme power in the land. A monarch like Charles, who believed in the Divine Right of Kings, wasn't going to swallow that, and he refused. The Scots lost patience and handed him back to the English.

Parliament placed Charles under arrest at Hampton Court Palace. But he became afraid that his guards meant to kill him. On November 11, 1647, he escaped by night. He rode south as fast as he could go. After three days, Charles reached Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, off the south coast of England. He demanded protection from the governor of the castle, who let him in.

The reenactment of Civil War and other battles is a popular activity among historically minded societies in England. Recreating the 17th century setting requires a great deal of careful research into costumes, hairstyles and weaponry.

A year later, on December 1, 1648, army officers arrived at the castle. They forced King Charles to go with them. He ended up in Hurst Castle on the English south coast. His room was small and dark with only a slit for a window.

Meanwhile, Oliver Cromwell had given orders for the king to be tried in London’s Westminster Hall. No king of England had ever been tried by his own subjects before. The trial opened on January 20, 1649.

Charles was accused that ‘out of a wicked design to erect…an unlimited and tyrannical power…traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament and the people (they) represented.’ The judges refused to call the king by his title. Instead, they called him plain ‘Charles Stuart’.

King Charles I’s death warrant, signed by 59 Parliamentary soldiers, including Oliver Cromwell. Many more were summoned to attend Charles’ trial at Westminster Hall, but most of them balked at the idea of passing a death sentence on their king.

Charles would not defend himself, since he did not recognize that the court had any right to try him.

‘I would know by what power I am called hither….’ Charles said. ‘I would know by what authority, I mean lawful…. Remember, I am your king, your lawful king…a king cannot be tried by any superior jurisdiction on earth.’

The court was not impressed. All that remained now was to find Charles guilty and pass sentence. The sentence was death. Fifty-nine soldiers, including Oliver Cromwell, signed the death warrant. A large scaffold was built outside the Banqueting Hall in London’s Whitehall.

January 30, 1649 was a bitterly cold day. Charles asked for two shirts to keep him warm because, he said: ‘The season is so sharp as probably may make me shake, which some observers may imagine proceeds from fear.’

Charles was taken to the scaffold. A vast crowd was there to watch. When he spoke to them, it was clear that for Charles, the Divine Right of Kings was still very much in force:

‘I must tell you that the liberty and freedom [of the people] consists in having of Government, those laws by which their life and their goods may be most their own. It is not for having share in Government, that is nothing pertaining to them. A subject and a sovereign are clean different things.’

Charles laid his head on the block. The executioner’s axe swung. He cut off the king’s head with a single blow. As he did so, wrote an eyewitness, ‘there was such a groan by the thousands then present, as I never heard before, and desire I may never hear again!’

Eight days later, Parliament abolished the title and office of king. On May 19, the monarchy was abolished, too. For the first and only time in its history, England had become a republic.

This painting by an anonymous Victorian artist depicts the future Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, gazing at the body of the executed King Charles I. The king’s head would have been reattached to his body before it was placed in the coffin.

The crown, orb, sword and other regalia used at the coronation of King Charles II had to be newly made for the event, because Parliament had sold off the existing regalia.