The English Republic was ruled by Parliament, which was dominated by Puritans. Puritans were killjoys who set out to get rid of everything they thought sinful and evil.

![]()

Adultery meant a death sentence. If a man killed his rival in a duel, he could be charged with murder. Puritans made special targets of swearing, gambling and drunkenness. They closed public houses on Sundays and fast days. Swearing was punished by fines. The amount depended on who had done the cursing. A duke was fined thirty shillings, a baron twenty shillings, a country squire ten and everyone else three shillings and four pence. That was only for the first crime. All fines were doubled the second time around.

Puritans were always on the lookout for wickedness and opportunities for same. This was why the playhouses – ‘dens of vice and immorality’ – were closed. Traditional pastimes such as bear baiting and cock-fighting were stopped. So was ‘lewd and heathen’ maypole dancing.

Dyed clothing of any kind was out. It was against the law to be caught wearing lace, ribbons or decorative buttons. Puritans frowned on long hair, too. England and its people had a very dismal time while Puritans ruled.

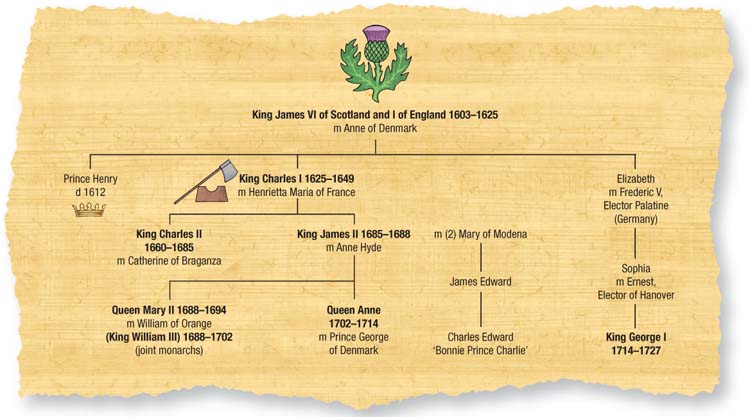

But the Puritans had made a big mistake when they abolished the monarchy. Monarchy and love of the monarchy were deeply ingrained in English tradition. There was a certain magic about the monarchy. People missed it so much that in 1657, Parliament made an unusual offer: they invited Oliver Cromwell, now Lord Protector, to become king. He laughed off the very idea. Cromwell knew the people did not want any old king: they wanted the real thing. And that meant Prince Charles, son of King Charles I, who was in exile.

Beyond this, Puritanism had a serious weakness. It depended on Cromwell and Cromwell alone. Once he died, in 1658, their regime fell apart.

Cromwell’s successor as Lord Protector was his son, Richard. Richard Cromwell was not the man his father had been. During the 20 months he was in charge, England sank into anarchy. One of the worst aspects was that many soldiers went unpaid. They began to wander around England, stealing food, money and anything else they needed.

Richard Cromwell was so useless that he was given the nickname ‘Idle Dick’. He knew he was out of his depth. So he bolted. On May 16, 1659, Cromwell disappeared from London. He fled to Paris, then Italy. He even took a false name: John Clark. His wife never saw him again.

With Idle Dick gone, there was no one to rule England. It was now imperative that the king return. Charles had waited 11 years to get his throne back. He had made one attempt to seize it by force, in 1651, but it failed. After Charles’ army was defeated at the battle of Worcester on October 14, Charles had to go on the run. Oliver Cromwell published a poster offering £1,000 for his capture. Charles was forced to hide in an oak tree to escape his pursuers. Today, the many English pubs called ‘Royal Oak’ are reminders of this incident.

Hundreds of English public houses are named ‘Royal Oak’ after an incident that took place on October 14, 1651, when Charles II was forced to hide in an oak tree while escaping from his defeat at the battle of Worcester.

A great moment for Charles II after eleven years of exile: he is being rowed toward Dover, where he landed back on English soil after being restored to his throne. Charles received a joyous greeting from his subjects.

After his defeat in 1651, Charles disguised himself. He blackened his face and donned a shabby old suit of clothes. After skipping from town to town, with Cromwell’s men in hot pursuit, he managed to sail back to France. But nine years later, Charles’s great moment arrived at last: General Monck, a senior officer in the Army, invited him to return as king. On May 29, 1660, Charles’s 30th birthday, he entered London in triumph. Londoners turned out by the thousands to welcome him. John Evelyn, the diarist, wrote:

‘The triumph of above 20,000 horse and foot brandishing their swords and shouting with inexpressible joy: The ways were strewed with flowers, the bells ringing, the streets hung with tapestry, fountains ran with wine …trumpets, music and myriads of people flocking…so they were seven hours in passing the City (of London) even from two in the afternoon till nine at night.’

That night, there were fireworks and illuminations over the River Thames. Spectators crowded into boats and barges. There were so many, Evelyn wrote, ‘you could have walked across (the river)’.

King Charles had his own way of celebrating his return. Nine months later, on February 15, 1661, Barbara Villiers, one of his many mistresses, gave birth to a daughter. Known as Anne Palmer, she was one of the king’s 15 illegitimate children.

Taking mistresses was almost the only entertainment Charles had while in exile. He was not fussy about his choices. Any curvy, good-looking woman who caught his eye was invited to share the royal bed. The most humble, and the most delightful, was Nell Gwynn. She came from the slums of London’s East End. Her first job was hawking fish around the richer parts of London. She was spotted by one Madame Ross, a brothel keeper. So, at only 12 or 13, Nell became a prostitute.

Nell Gwynn was the most famous and least pretentious of Charles II’s many mistresses. Charles first saw her at the theatre in London, where she was selling oranges to the audience. Later, Nell became one of England’s first actresses.

But she was no ordinary prostitute. Nell Gwynn was a lively and amusing charmer. Later, Samuel Pepys, the diarist, called her ‘pretty, witty Nell’ and it suited her. She was ambitious, too. She did not intend to remain just another disposable girl in a brothel. London’s stage gave her the chance to move on.

The playhouses reopened after King Charles’ return. They showed new, sexy ‘Restoration’ comedies. These rude, crude, suggestive plays made Puritans rigid with disapproval. But King Charles loved them. He was often among the audience at one of the newest, The King’s House, which opened in 1663. There he first saw Nell Gwynn. She sold oranges to members of the audience.

The charming Nell was eyed appreciatively by almost every man within range. She was an accomplished flirt and took several lovers. One was an actor, Charles Hart. He realized Nell would make a splendid actress. At this time, actresses were quite new to the English stage. Previously, female roles had been played by males.

Another actress was Moll Davis, one of King Charles’ mistresses. Moll hated Nell Gwynn and Nell hated her back. To get revenge on Moll, she played a wicked trick. One night early in 1668, Moll was about to sleep with King Charles. A few hours earlier, Nell invited Moll to eat some sweetmeats she had prepared. Moll did not know that the sweetmeats contained a hefty dose of the laxative jalap.

That night, the jalap went to work. Moll was seized by violent attacks of diarrhea. There was no lovemaking. What the king thought is not known. But he was probably amused by the joke – and the delightful young woman who had played it. Soon he had added Nell to his roster of mistresses.

Another ‘prank’ – though this one considerably more dramatic – that appealed to Charles’ sense of fun was an attempt, in 1671, to steal the Crown Jewels from the Tower of London. The would-be thief was Colonel Thomas Blood, son of an Irish blacksmith. Blood had led a vivid life. In 1670, he kidnapped the Duke of Ormonde, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Blood was sentenced to death and was about to be hanged at Tyburn in London when a last minute reprieve arrived. Blood fled. A reward of £1,000 was offered for his capture. But he was not caught and set out to steal the Crown Jewels.

Colonel Blood disguised himself as a parson. He spent time getting friendly with Talbot Edwards, Master of the Jewel House at the Tower. Their friendship went so far that the two men agreed to a marriage between members of their families. This marriage was to have taken place at the Tower on May 9, 1671.

That day, with two accomplices, Blood arrived at the Tower. Talbot Edwards suspected nothing until Blood produced a mallet from beneath his cassock and began to beat him over the head. Edwards fell unconscious to the floor.

Blood seized the king’s crown and used the mallet to flatten it so it would fit into the pocket of his cassock. One of his accomplices seized the orb and hid it inside his breeches. Meanwhile, the other gang members tried to file the sceptre in half.

Just then, Edwards’ son Wythe arrived unexpectedly. When he found his father lying on the floor bleeding, he raised an alarm. At this, Blood and his accomplices fled. But they were caught before they got away.

When King Charles was told what had happened, he was so amused he gave Blood a pardon. He also gave him a large pension of £500 a year and invited him to come to court. It was all part of the ‘fun and games’ that returned to England when Charles, the ‘Merry Monarch’, came back as king.

But the Merry Monarch’s reign was not all fun. There was a vicious campaign of revenge against the men who had signed his father’s death warrant. Ten of these king-killers were hung, drawn and quartered at Tyburn in London on October 20,1660. One, a soldier, sat up while he was being drawn and hit his executioner.

But King Charles had other scores to settle. His main purpose in life was ‘never to go on his travels again’. He would do anything to keep hold of the throne he had waited for so long. The most important item was to get rid of Parliament.

Kings had always relied on Parliament for money. If Parliament did not like a king’s policy, they would refuse to pay up. The solution was for Charles to obtain his own store of cash. In 1670, he signed the Treaty of Dover with King Louis XIV of France. Parliament was supposed to believe that with this treaty, Charles would help Louis with his wars in Europe. But there was a secret clause: Louis agreed to give Charles large sums of money. When Parliament became suspicious, Charles lied, declaring there were no secret clauses. But his hands trembled as he spoke.

All the same, Louis’ money gave Charles what he wanted. He was able to dissolve Parliament in 1681. He ruled without it for the rest of his life. This killed two birds with one stone. Parliament could no longer blackmail the king by refusing him money. But they also could not stop his heir, his brother James, Duke of York, from succeeding to the throne.

James was a Roman Catholic. When he became king, he sought to return England to the Catholic Church. This caused an uproar in Parliament. Several attempts were made to exclude James from the succession. None succeeded. James’s most powerful backer was King Charles himself. James was the rightful heir, so he argued, thus James must be king.

Titus Oates received far worse punishment than simply being pilloried, as shown in this illustration. Found guilty of perjury, he was imprisoned for life in 1685, but was released in 1688 after the dethronement of King James II.

The Catholic King James II caused tremendous upheaval and much violent protest with his attempts to return England to the jurisdiction of the Pope in Rome. He escaped the fate of his father, Charles I – execution on the block – but was forced into lifelong exile.

But anti-Charles conspirators were also at work. In 1678, two jokers, Titus Oates and Israel Tonge, decided to stir things up. They hatched the ‘Popish plot’. This plot was all hot air. It never existed. But people were so nervous that many believed it was true.

The ‘plotters’ were Catholic Jesuit priests who planned to kill King Charles. This would make sure Catholic James became king. Then the Popish Plot became known to a London magistrate. He looked into it and came to the conclusion that it was all lies. All the same, Titus Oates went on trial for perjury and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Next, in 1683, a group of conspirators hatched another plan, the ‘Rye House Plot’. This time they really meant to kill. Their targets were not only James, but King Charles as well. That, they thought, would eradicate the risk of having a Catholic king on the throne of England.

This is Rye House near Hoddesdon in Hertfordshire, which was at the centre of a republican plot hatched in 1683 to kill King Charles II and his brother, James, Duke of York, on their way back from the horseracing at Newmarket.

One of the conspirators was James, Duke of Monmouth, King Charles’ first illegitimate son. He was vain, stupid and ambitious. Monmouth wanted to be king himself and thought that this was the way to do it.

The plot focused on Rye House farm at Hoddeston, Hertfordshire. King Charles, a keen race-goer, was a regular visitor to the Newmarket races. A narrow lane near Rye House was on the route to Newmarket from London. When King Charles and his brother James used it to return from the races, the plotters intended to ambush and kill them.

But things did not work out as planned. A fire broke out at Newmarket while Charles and James were there. Racing was abandoned. This meant they left Newmarket and rode along the lane much earlier than expected. That, of course, saved their lives.

The conspirators were arrested. One, the Earl of Essex, committed suicide before his trial. But three others were found guilty of treason. There were suspicions that much of the evidence had been made up, and that some of the prosecution witnesses had lied. All the same, the conspirators were beheaded - except Monmouth. King Charles was too fond of him to punish him.

Two years later, on February 5, 1685, Charles died. Just as he had always wanted, James became King James II. But soon thereafter, Monmouth tried again to seize the throne. He headed an armed rebellion against the new king. Monmouth’s army was overwhelmingly defeated at the battle of Sedgemoor, in Somerset, on July 6, 1685. He managed to escape from the battlefield and went on the run.

This painting shows the joint monarchs King William III and Queen Mary II. William was invited by Parliament to save England from the Catholic ‘menace’ that threatened the country because of the ‘popish’ policies of King James II.

Monmouth was found a week later, hiding in a ditch. He was accused of treason and executed on July 15. But axeman Jack Ketch was a bungler. He chopped away at Monmouth’s neck five times. Even then, he did not kill him. Monmouth’s body was still twitching. Ketch threw down the axe in disgust. ‘I cannot do it,’ he said. ‘My heart fails me.’ In the end, a knife was used to hack off Monmouth’s head.

Even though he had fought hard to make sure James succeeded him, King Charles knew exactly what would happen when he did. He predicted that James would ruin himself within three years. His calculation was perfect.

James lost no time returning England to the Catholic faith. Protestants seethed as he gave Catholics important government and other official posts. They gritted their teeth in rage as James opened negotiations with the Pope to return the English church to his jurisdiction.

The only comfort James’ opponents had lay with his two daughters, Mary and Anne. Both were Protestants. Mary was married to the prominent Dutch Protestant, William of Orange. So even if they had to put up with the Catholic James for now, he would be succeeded in time by a Protestant reigning queen – maybe two.

Then, in 1688, something happened that changed the whole picture. On June 10, King James’s second wife, Mary of Modena, gave birth to a son, James Edward, after 15 years of marriage. James Edward’s birth after such a long time surprised everyone, even his parents. It also placed James II’s enemies on alert.

James Edward was now heir to his father’s throne. That meant an endless line of Catholic monarchs on the throne of England. It was too much. James had to go. A group of seven prominent Englishmen sent a secret message to William of Orange. They asked him to bring an army to England and throw James out.

It was a desperate move. Undoubtedly these men were committing treason. But no one was going to accuse them of that when England had to be saved from the Catholic ‘menace’.

William of Orange landed at Torbay, Devon, on November 5, 1688. As he advanced toward London, James’s army retreated. During the retreat, they began to desert. James knew he was on a losing streak. He became terrified. He thought he was going to be beheaded, as had been his father, Charles I.

James tried to escape. He attempted to cross the English Channel to France on December 11, 1688. Though disguised as a woman, he was recognized by fishermen who took him back to England.

William and Parliament did not want James back. They would have preferred it if he had escaped into exile. James was given every chance to try again. He managed to get to France on his second attempt, Christmas Day, 1688.

Now, nothing stood between James’s daughter, Mary, and the throne – except that her husband William did not want to be a mere consort. He wanted to be king. It was King William or no William, he told Parliament. Otherwise, he threatened to return home and let the English stew.

Parliament had to agree, even though Mary was true heir to the throne. Parliament could not sidestep her, so the throne was offered jointly to William and Mary. They became King William III and Queen Mary II. It was the first and only time England had two monarchs at the same time.

Parliament’s offer was not without strings, however. They had had more than enough of monarchs who ranted on about the Divine Right of Kings and did as they pleased.

In 1689, Parliament solved this problem by creating a ‘constitutional’ monarchy. This meant that monarchs lost some of their rights, such as to make war or raise taxes. The only income they could have was that granted by Parliament. The polite way of describing constitutional monarchy was that the monarch reigned but did not rule. What it really meant was that Parliament ‘fixed’ the monarchy so it could no longer rock the boat.

The first order of business for William and Mary was to get rid of ex-King James once and for all. In 1690, James brought an army to Ireland. But William easily defeated him at the Battle of the Boyne on July 1. James fled back to France. He never tried to invade again.

In 1689, the Scots had tried to fight for him. They rebelled against the new king and queen. They were defeated, and the English were very suspicious of them. The Scottish clans were ordered to declare loyalty to William and Mary. The deadline was New Year’s Day, 1692. But a terrible misunderstanding occurred and because of it, a shocking slaughter took place.

Scots never forgave King William for the Massacre of Glencoe. But William’s problems were getting worse. He had no children. And there was no hope of any children after Queen Mary died of smallpox in 1694. William was heartbroken. Outwardly, he was something of a cold fish. But he collapsed in tears when told Mary had smallpox. The shock was so great that William became paralyzed for a time.

The ‘woman’ descending the steps in this picture is no woman at all, but the fleeing King James II in disguise. Despite the deception, James was recognized the first time he tried to flee, but he was helped to get away a second time.

Queen Anne, second daughter of James II, was the last Stuart monarch. In 1694, after her elder sister Queen Mary II died, Anne waived her right of succession and allowed her brother-in-law, King William III, to take the throne. She succeeded him after he died in 1702.

William refused to marry again. This meant that Mary’s sister, Anne, became his heir. Unlike Mary, Anne had given birth to many children – 17 in all. But something was terribly wrong with each of them. All died while still young. The last, William, Duke of Gloucester, survived longer than the others. But in 1700, when he was 11, William died, too. He suffered from water on the brain and was weak, slow and stupid. But as long as he lived, he was the last hope of the Protestant Stuart monarchy.

Two years later, on February 21, 1702, William III was riding in Richmond Park, near London, when his horse stumbled on a molehill. At first, William’s doctors thought the only damage was a broken collarbone. But the accident was much more serious than that. William’s hand became swollen. He could not sign documents and instead had to use a stamp. His doctors tried everything – powdered crab’s eyes, pearled julep and sal volatile. Nothing worked. William died on March 8. For centuries afterwards Scots drank toasts to the mole – ‘the little gentleman in the black velvet coat’ – because it had caused the hated king’s death.

The plain, dull and obstinate Anne, who now succeeded to the throne, was the last of the Stuart monarchs. Although she was married and had given birth to many children, Anne was probably a lesbian. All her close companions were women. A crude pamphlet was written about Queen Anne’s ‘orientation’:

When as Queen Anne of great renown

Great Britain’s sceptre swayed

Beside the church, she dearly loved

A dirty chambermaid.

Anne, it seems, was the ‘girl’ in lesbian relationships. She was completely dominated by her most famous female companion, Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, a very strong-minded woman. She and her husband, John Churchill, were ancestors of Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Queen Anne was the last of the Stuart monarchs. When she failed to produce an heir, the country was thrown into intense debate. Her eventual successor, George I, was only 52nd in line to the throne, but at least he was a Protestant.

Between them they had Queen Anne just where they wanted her. Anne and Sarah had been childhood friends. Sarah used their friendship to grab all sorts of titles and rewards. These titles came with plenty of money and land. Sarah also engineered a dukedom for her husband: he became Duke of Marlborough in 1689. Later, when Anne was queen, the duke won four splendid victories against the French. With this he shot to fame as England’s greatest soldier. Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire was built especially for him as a reward.

Queen Anne disliked pomp and pageantry. She hated the formality of the royal court. So she relaxed by playing a game with Sarah Churchill. Anne called herself ‘Mrs. Freeman’. Sarah called herself ‘Mrs. Morley’. They pretended they were not queen and subject, rather two ordinary women who enjoyed a chat and gossip and a game of cards.

This was a mistake. Sarah took the game seriously. Anne was a bit of a mouse, plain and awkward. Sarah was a beauty and knew it. So it was not long before she was boldly ordering the queen around and throwing her weight about.

This could not go on indefinitely. In 1707 Anne and Sarah had a big row. Sarah stormed out of the court. The quarrel was so serious that Sarah and her husband left England, too. They did not come back until after Anne’s death.

But someone else was waiting to take over from Sarah Churchill. Mrs. Abigail Masham was a relative of Sarah’s. Indeed, it had been Sarah who arranged for Mrs. Masham to be appointed ‘Woman of the Bedchamber’ to Queen Anne. Sarah soon found it was the wrong move. Abigail Masham was a bitch. She wormed her way into Queen Anne’s affection, telling terrible tales about Sarah to the queen.

Sarah was furious. She wrote of ‘the black ingratitude of Mrs. Masham, a woman that I took out of a garret and saved from starving.’

But Abigail remained Queen Anne’s closest companion for seven years. In that time she lined her own pocket with profits from financial deals. She kept other would-be friends of the queen away by plotting against them. But when Anne died, Mrs. Masham’s power vanished overnight.

Anne’s health had never been good. It was made worse by her long series of miscarriages and stillbirths. The deaths of her children depressed her greatly. In 1708 her husband, Prince George of Denmark, died. Anne had adored him and was never the same again.

Anne’s childlessness was not just a personal problem. It was a national one as well. In fact, it was an emergency. The Catholic Stuarts were still around, still aiming to seize the English throne. To prevent them from succeeding, a Protestant heir had to be found. The nearest was Sophia, Electress of Hanover in Germany. Her mother Elizabeth had been a daughter of King James I, the first Stuart monarch.

Queen Anne hated Sophia. She would not even allow her name to be mentioned at court. So she was delighted when Sophia died in June 1714, since she now would not be Queen of England. But within three months, Anne herself was dead.

The king who now succeeded to the throne as the first Hanoverian monarch of England was Sophia’s son George, Elector of Hanover. George was Protestant, which is what Parliament wanted. It was enough to keep the English loyal to him when James Edward Stuart and his followers, the Jacobites, attempted but failed to seize the throne in 1715.

But George did not have much else about him to appeal to his subjects. They had endured bad kings, mad kings, despots, usurpers and weaklings. But, as the English were soon to discover, the Hanoverians were something else.

George II was the last king of England to lead his troops into battle, at Dettingen in 1741. At the time he was 60, a lot older than this illustration makes him appear.