A glass of brandy may have dulled the shock for a time, but an awful reality was still there when the effect wore off. Prince George’s future bride stood before him at their first meeting looking an absolute fright.

![]()

Caroline was dressed in a robe and cloak with a beaver hat on her head. The robe was in a shade of sickly green with satin trimmings, festooned with fussy loops and tassels. This was the best her attendants could do to hide her pudgy figure.

Caroline’s face was covered with garish makeup. Somewhere underneath were her fine, fresh complexion and rosy cheeks. She looked like a clown. And that was not all. Close up, Caroline reeked. She smelled unwashed. Prince George reeled. He was very strict about hygiene and regular bathing.

Somehow, Prince George managed to compose himself and behave graciously. But it took a stupendous effort. The prince had to contain himself again when he took Caroline to a pre-wedding dinner. She prattled on and on about the latest gossip, including talk about the prince’s latest mistress, Lady Jersey. Her language was crude, coarse and smutty.

After a while, George could stand the situation no longer and got thoroughly drunk. He was still hung over when the marriage ceremony took place on April 8, 1795. George spent most of his wedding night in a drunken stupor, asleep on the floor next to the fireplace. But somehow – though he probably never remembered how – he fulfilled his royal duty. Caroline, the new Princess of Wales, became pregnant on her wedding night.

In truth, Caroline was not all that impressed with George, either. At one time, he had been a slim young man, and handsome too. Not any more. At age 33, years of self-indulgence and overeating had taken a toll. Caroline was disappointed to see how fat and puffy he had become.

In spite of having a distinct aversion to one other, George and Caroline made some effort to live together. They spent the summer and autumn of 1795 at Brighton Pavilion, on England’s southern coast. This lavish, oriental-style building – still one of the major sights of Brighton – had once been George’s most expensive extravaganza. But while the couple were there, George’s drinking pals descended on them, along with their women. The quiet honeymoon in Brighton turned into a riotous drinking party.

This did not help George and Caroline learn to tolerate each other, and soon they stopped trying. Caroline was spoiled, rebellious and vain. It had once been said that unless she were kept on a tight leash, she would go wild. George did not bother trying to rein her in.

Once their daughter, Princess Charlotte, was born on January 7, 1796, Prince George made moves to distance himself from his marriage. Charlotte was but a few days old when her father drafted a will disinheriting Caroline.

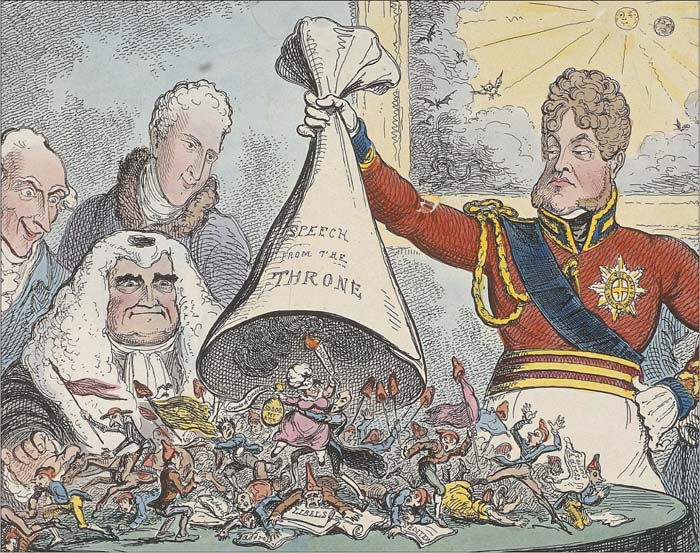

Cartoonists often caricatured Prince George. His huge bulk was due to constant overeating. He fancied himself as a dandy and wore exotic clothes. This contemporary caricature shows him with an equally gross ‘friend’.

Maria Fitzherbert was the great love of King George IV’s life. He broke the law in 1785 when he married her without his father’s permission. George left her from time to time to dally with mistresses, but he always returned.

After his fling with Lady Jersey, George was struck with a yearning for Maria Fitzherbert once again. In a nearly hysterical mood, he wrote vowing eternal love for ‘my wife in the eyes of God and who is and ever shall be mine.’ Another letter, this time to Caroline, was totally different. It began ‘Madam’, and went on to state his desire for a total and permanent separation.

George and Caroline never lived together again. But they were never divorced, nor was this the end of their relationship. The couple would be bound together in mutual hatred for the next 25 years.

Caroline was not the sort of woman to retire to a quiet, discreet life in the country, where everyone might forget about her. She was too vulgar, too outlandish, for that. She did move to the country, but that was about it. Her new home was in Blackheath, on the southern edge of London.

Before long, Caroline was shocking the locals with her antics. She received a stream of ‘gentleman callers’. Tales of multiple adultery began to circulate and spread. Caroline got her clutches on one William Austin, young son of a dockyard worker, and claimed he was her and Prince George’s son. Fortunately, government investigators proved the story false. They went on to dig up evidence about Caroline’s sex parties. But they were unable to prove anything, despite the gossip.

Meanwhile, Prince George’s longing for Maria Fitzherbert had worn off again. He took a new mistress, Lady Horatia Seymour. After that, it was back to Maria again. She held George off for four years, possibly to teach him a lesson. But in 1801, she agreed to live with him again. Maria managed to hang on to George for ten years – a record for him. But he wandered off again, this time with yet another mistress, Lady Hertford.

In 1811 King George III’s illness returned and he became permanently mad. He had violent fits. He refused to eat. He imagined that his son Augustus, who had died in 1783, aged four, was still alive. He lost all sense of time, place or reality and lived in a dream world. The one thing he remembered, it seems, was how to play the harpsichord.

This time, it was hopeless. The king was declared incurably insane in 1812. He was shut away in his palace and spent his days wandering around his rooms, mumbling to himself and clutching the Crown Jewels.

George was appointed Prince Regent at last. He took the oath on February 6, 1811. But he still had to deal with the troublesome Caroline. The king’s madness had been a disaster for her, for in spite of everything, King George had protected her. Now, that protection was gone, and she was in the hands of a husband who detested her. He soon made the most of it.

He used Princess Charlotte as a psychological weapon with which to beat his wife, refusing to let her see their daughter. Caroline was up to the challenge. She had allies in Parliament and used them to force a Parliamentary debate. The vote went to Caroline.

With Parliament against him, the prince had to give in. But he hit back by throwing Caroline out of her apartments at Kensington Palace. He also forbade Charlotte to see her – no matter what Parliament had said.

Caroline’s response was to make several well-publicized public appearances. She posed as the victim of a cruel husband, but cheerfully so. The ploy worked. Crowds cheered her. At the same time, they booed the Prince Regent.

The warfare between George and Caroline moved on to the next round. George decided that Princess Charlotte should marry Prince William of Orange. William was an unpleasant young man. Even so, Charlotte was expected to obey her father. But, as was her mother, she was stubborn and loud-mouthed. It was not long before she had picked a quarrel with William.

This cartoon shows ‘the Royal Extinguisher’ – King George IV - who finally triumphs over his dreadful wife Caroline by placing a cone made of paper over her and a crowd of Jacobites – supporters of the ousted House of Stuart.

Charlotte fled to Caroline’s house in Connaught Place, London. Caroline was not there. She was at Blackheath. The Prince Regent’s brothers came after her. They badgered her to obey her father. By this time her war with the Prince Regent had exhausted Caroline. This latest fight was too much. She joined in and told Charlotte to stop making trouble and marry William.

Charlotte had her own cunning way of dealing with William. She blackmailed him by demanding that, as second in line for the English throne, she must remain in England after their marriage. Next she told William that Caroline must come and visit whenever she wanted. That was it. The very thought of sharing living space with Europe’s most scandalous mother-in-law was the last straw for William. He refused her requests. Charlotte broke off the engagement.

Princess Charlotte eventually married another prince, Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, in 1816. However, she died after giving birth to a stillborn son. Caroline was in Italy when she heard the news and immediately went into deep mourning for her daughter. In England, the Prince Regent collapsed in a dead faint on hearing the tragic news. He recovered, but was so distressed he was unable to attend the funeral.

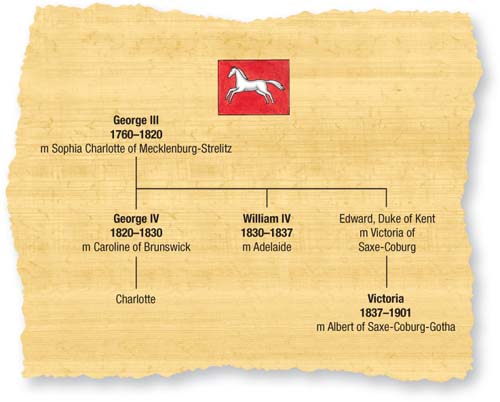

This, though, was not merely tragic family loss. It created a crisis. Charlotte had been the only heir to the throne in her generation. The other heirs to mad King George III were Charlotte’s elderly uncles and aunts, none of whom had any legitimate children.

So Parliament sent a petition to four of Charlotte’s uncles to marry and produce legitimate heirs. It meant leaving their mistresses, which caused them pain. All the same, they did their duty for the sake of the Hanoverian line. They took wives and had children. Unfortunately, many of the infants died.

For a time, even the Prince Regent considered divorcing Caroline and marrying again. But Caroline refused to let him. She did not think her sexual adventures in Europe were sinful, and prepared to fight any divorce action the prince might bring.

The prince set up a commission to find grounds for divorce. Caroline responded by promising to create a storm of protest in England. It was a shrewd move. Details of the prince’s own private life were bound to come out. All the same, Caroline tried another tack. She offered to set aside her rank as Queen of England when George became king. In return, she wanted George to give her a large sum of money. He refused, ending thoughts of divorce. The couple remained married, shackled together in mutual loathing.

Caroline was still on course to become Queen of England. As long as King George III was still alive, that remained a remote possibility. But on January 29, 1820, King George died. He had become a tragic figure, far gone into madness. He was deaf and blind. His white, gaunt face was sometimes observed, staring out the palace window, seeing nothing. His beard had grown long and straggly. He knew nothing about the death of Princess Charlotte, or the marriages of his sons. He was even unaware his queen, Charlotte, had died in 1818.

The Prince Regent succeeded his father as King George IV. As far as her rights were concerned, Caroline was now queen. But as far as her husband was concerned, he was not going to let her anywhere near the throne.

Time for the new king to act was limited. He had to get rid of Caroline before his coronation. In fact, the coronation was postponed while the king made another attempt to unhitch himself from his outrageous queen. He asked Parliament to pass a Bill of Pains and Penalties. This set out Caroline’s numerous sins. The attempt failed. The only evidence offered was circumstantial – albeit Caroline’s sexual antics had been the subject of frequent gossip. The Bill of Pains and Penalties had to be dropped. Londoners, who loved Caroline, went wild with joy and celebrated for three days and nights.

Caroline chose this moment to make a triumphant return to England. Everywhere she went she was fêted and saluted. George IV, by contrast, was subjected to vile insults. Obscene graffiti were scrawled on the walls of Carlton House, his private London residence. And not only there. ‘The queen forever! The king in the river!’ were slogans scrawled on the walls of the Russian Embassy in London. George IV got the message. He left London for his country cottage at Windsor, Berkshire. There, he waited for ‘Caroline fever’ to die down.

Nine weeks passed before George thought it safe to return to London. To make sure, he took a troop of Life Guards with him. He was relieved that the crisis seemed to have passed. When he went to a play at London’s Drury Lane, he was applauded. The same happened when he went to see another play at Covent Garden.

This drawing of King George III depicts him at the age of 72, in his Golden Jubilee year of 1810. But tragedy was fast approaching at this time: King George went mad once again, and this time there was no chance that he would recover.

After this, the king felt confident enough to fix another date for his coronation – July 19, 1821. Queens of England had their own special coronation, after the king’s. But George was confident enough now to tell Caroline she could not take part. Her name had already been removed from the prayers to be said at the coronation ceremony. She had been pestering him to have her name put back, to tell her what robes she should wear, to name the attendants who would carry her train.

But George IV was determined that his coronation would be a one-man show. Caroline was not deterred. She was determined to crash the ceremony, planned for London’s Westminster Abbey. Failing that, she would create mayhem. Caroline was counting on her popularity with London crowds. The king knew she would make a terrible scene, so he took precautions to prevent her even from entering the abbey.

Twelve days after his coronation, George IV went aboard the royal yacht for a state visit to Ireland. The yacht was at anchor off the Isle of Anglesey, north Wales, on August 6, 1821, when news arrived that Caroline was dying. She had been taken ill at Drury Lane. Medical treatments at this time were extremely brutal, often causing the patient’s death. But such treatments were all Caroline’s doctors knew. So they bled her and gave her hefty doses of calomel and castor oil.

The doctors believed she would somehow recover. Instead, she died on August 7. For once, George IV acted decently. He remained on Anglesey during the week of Caroline’s funeral. Five days of official mourning had been declared. The king waited until they had passed before making his entry into Dublin.

But it was Caroline who had the last word. At her own request, her coffin was inscribed with the words: ‘Caroline of Brunswick, the Injured Queen of England’. Even the King of England was unable to do anything about that.

William IV succeeded his brother George IV on the throne in 1830. He had never expected to become king and was so delighted that he drove around London in his carriage greeting his subjects and shaking them by the hand.

Victoria, niece of George IV and her predecessor William IV, came to the throne at age 18 in 1837 determined to repair the good reputation of the royal family after the outrageous activities of the Hanoverian kings. The result was an era of strict morality.

George IV was King of England for ten years, until his death at Hampton Court on June 26, 1830. His heir was his brother William, Duke of Clarence, who became King William IV.

Like other sons of King George III, William was a bit of an oddity. He even looked peculiar. Aged 64, William had a round face, very red cheeks and a distinctly unroyal quiff. When the coins of his reign were minted, designers deliberately left out the quiff.

William was awakened at six in the morning and told he was king. He showed no emotion. Instead, he shook the messenger’s hand and went back to bed. His only comment was that he had ‘always wanted to sleep with a queen’. His wife Adelaide had, of course, just ascended from Duchess of Clarence to Queen Consort of England.

Later the same day, he stuck a small piece of black crepe in his hat and went out riding at Windsor. But William IV was not as nonchalant about succeeding to the throne as he pretended to be. As a younger son of a king, he had never really expected to be king himself. When it actually happened, he was thrilled.

A few days later, he went riding around London in his coach. He stopped here and there to buttonhole passers-by, shake them by the hand and tell them how delighted he was to be their king. It was embarrassing, but somehow heartwarming.

Unfortunately, William IV came to the throne without legitimate heirs of his own. As Duke of Clarence, William had married Adelaide in the royal rush for a wife after the death of Princess Charlotte. They had two daughters, but both died in infancy, and there were no children after that.

William’s heir was his niece, Princess Victoria. She was the daughter of his younger brother, Edward, Duke of Kent – another participant in the royal rush to marry. Victoria’s mother, Victoire of Saxe-Coburg, kept her daughter strictly under her control. Victoire’s main aim was to keep the girl well away from the influence of disreputable Hanoverian relatives.

Predictably, William IV became at odds with Victoria’s mother. His greatest wish was to live long enough for Victoria to reach the age of majority, 18: if he could do that, he could prevent her mother from becoming Regent. The king just made it. William IV died on June 20, 1837. Victoria had turned 18 the month before, on May 24.

Not surprisingly, Princess Victoria grew up to be narrow-minded and self-opinionated. She was also a terrible prude, and tended to be obsessive. In 1840, she married her first cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, who was even more of a prude than she was. He once said that the thought of adultery made him feel physically sick.

Albert set the pace for his wife’s reign and for their private life. Hanoverian sleaze was out. Strict Puritan-style morality was in. Family respectability was to become the motto of Victorian England. More than that, the nine children of Victoria and Albert were to be role models for a new society: their example, so their parents resolved, would stand as a lesson on how to be royal, yet lead a pure life.

But there was one great big flaw in this plan. Victoria’s heir, the future King Edward VII, was pure Hanoverian. Strict morality meant nothing to him. Both as Prince of Wales and as king, he became the greatest royal womanizer since King Charles II. He gambled, he drank, he smoked – all to excess. His life was one long round of scandal that horrified his parents and left their high-minded plans in ruins.

Three royal generations: Queen Alexandra and King Edward VII (standing), the future George V and Queen Mary, and their son Edward (later King Edward VIII and after his abdication in 1936, Duke of Windsor).