Edward, Prince of Wales, known in the royal family as Bertie, began his life of scandal at a young age. In 1861, when he was 19, he was sent for military training to an army camp at the Curragh, in Ireland. It was there that he lost his virginity.

![]()

Bertie had spent his childhood in confinement at home, with his family. He was held captive by a very strict system of education. But more study and more application were required of him than he could reasonably manage. Bertie was not stupid, he was simply unacademic. Book learning, which he came to hate, meant nothing to him. He reacted by throwing tantrums, attacking his tutors and working himself into wild rages.

But in 1861, this repressed and immature young man had his first taste of what the outside world was really like. First of all, he met other young men, all training to be army officers. He found they had habits he had never heard of. One was making use of the services of the camp prostitute, a pretty young actress named Nellie Clifden.

One night, officers at the Curragh moved Nellie into the prince’s bed. The inevitable happened. Nellie made a man of him. But when the news reached Bertie’s parents, they were horrified. The incident became known as ‘Bertie’s Fall’, and Bertie was never allowed to forget it.

Prince Edward shocked his parents and Victorian society with his sexual antics and his association with high-life scandal. Less prudish types, however, had a sneaking admiration for Bertie, who broke the rules and got away with it.

Even worse, there was a tragic sequel. Not long after ‘Bertie’s Fall’, his father, Prince Albert, fell seriously ill. His doctors had no idea what was wrong. He had probably caught typhus from faulty drains at Windsor Castle.

Albert died on December 14, 1862, aged only 42. Queen Victoria went half-mad with grief, for she had idolized him. She went into mourning and remained so for the next 40 years, until she died. Bertie and his ‘Fall’ were blamed for causing Albert’s death. Victoria never forgave him.

But before Albert died, a cure for ‘Bertie’s Fall’ had already been arranged: marriage to a sensible wife who would keep tabs on him and stop his straying.

The royal houses of Europe were searched for a suitable bride for Bertie. Finally, the choice became the 18-year-old Princess Alexandra of Denmark. She had the one asset Bertie’s parents most wanted: she was extremely beautiful. Victoria firmly believed Alexandra’s physical beauty alone would make Bertie mend his ways. Victoria – and Alexandra – soon discovered differently.

Bertie and Alexandra were married on March 10, 1863 at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor. Queen Victoria cast gloom over the ceremony by attending clad entirely in black and observing from a high balcony.

What Victoria had not realized was that in having Bertie married, she was freeing him from her apron strings. Now, he would have his own household. In fact he had two homes, Marlborough House in London and Sandringham in Norfolk. He also soon had his own family: his first son, Prince Albert Victor, known as Eddie, was born in 1864. Above all, Bertie could now make his own social life. And a very riotous – not to say scandalous – social life it would be, too.

Queen Victoria, meanwhile, was involved in a scandal of her own. Victoria was a very emotional woman given, on occasion, to melodramatic conduct. She had not simply loved her husband, Prince Albert, she had adored and worshipped him. It was the same – according to gossip of the day – with her personal servant, or gillie, Scotsman John Brown. Brown was never anything but a best-liked servant. But after Albert’s death Victoria became so attached to him that it gave rise to gossip.

John Brown was based at Balmoral, the royal home in Scotland. He was no ordinary gillie. His intelligence was above average and he was a very good judge of human nature. Besides that, he had a way of talking Victoria liked. She hated all the bowing and scraping when royals were around. Brown, by contrast, spoke his mind. And he knew how to do it without being rude. For Victoria, he was a breath of fresh air.

Brown was unusually thoughtful and considerate. He knew Victoria loved white heather. So he kept an eye out for it in the countryside around Balmoral. Victoria was thrilled to receive bouquets of her beloved flower from her much-loved servant.

Despite her high position as Queen of England, Victoria was a dependent type of woman. She liked and needed to be cared for. Brown fulfilled her requirements. He became her constant companion, accompanying her wherever and whenever she wanted.

Brown also saved her life. On February 29, 1872, Victoria was about to go through the garden entrance to Buckingham Palace when a man named Arthur O’Connor pointed a pistol at her. John Brown leapt on him and knocked the weapon out of his hand. Brown pinned the man down until police arrived.

Later the queen awarded Brown a gold medal for his courage.

John Brown was often alone with the queen. He came to her bedroom after breakfast and sat with her while she looked through papers in confidential government ‘boxes’ – a task she had to perform every day. She saw more of Brown than of her own children.

Victoria’s children became jealous. They spoke of Brown as ‘Mama’s lover’. They may even have believed the gossip that Victoria and John Brown were secretly married. For a while, it became an ‘in’ joke to refer to the queen as ‘Mrs. Brown.’

After more than 20 years of devotion to the queen, John Brown died in 1883. Victoria was almost as distraught as when Prince Albert died. Her reaction was, of course, excessive. She put up a statue to Brown at Balmoral. She planned to write a poem in his praise. She ordered that Brown’s room should be kept exactly as it had been when he died. A fresh rose was to be placed on his pillow every day. The orders were carried out: a new rose appeared on the pillow every day for 18 years, until Queen Victoria died in 1901.

Bertie, of course, thoroughly disapproved of all this ‘romantic nonsense’ over John Brown. Victoria, in turn, thoroughly disapproved of Bertie. If anyone was disgracing the royal family name, so she thought, it was he.

She had a point. Bertie, as always, lived dangerously. Mostly his activities were kept under wraps. But it was inevitable that sooner or later, there would be a scandal that could not be hidden. The time arrived in 1870.

In February of that year, Lady Harriet Mordaunt confessed to her husband, Sir Charles, that she had committed adultery with several men. One of them had been Bertie.

Bertie protested his innocence. He knew the Mordaunts well. It was true he had written several letters to Harriet. But they were friendly, so he said, no more than that. Unfortunately, Sir Charles Mordaunt was not like other members of the English aristocracy. Most did not mind if the prince bedded their wives. They regarded it as a sort of compliment. But Sir Charles did not see why Bertie should get away with it. He threatened to name the prince as a co-respondent in his divorce case. This caused horror all around. It was one thing to gossip about royal goings-on, quite another to have it all spelled out in public.

But Bertie was saved when Sir Charles’ divorce case failed. Not because his wife was not guilty, but because she had been declared insane. Her ‘lovers’, royal and otherwise, were found to be in her imagination. It was a tragic outcome, but it got Bertie off the hook. After the divorce case, he had to put up with booing, hissing and catcalls whenever he appeared in public. But at least he had not been named as an adulterer by the court.

Judi Dench as Queen Victoria and Billy Connolly as John Brown in Mrs. Brown, a film made in 1997 about the relationship between Victoria and her ‘gillie’, or Highland servant. Some said that Victoria and Brown were married.

Bertie and Alexandra, Prince and Princess of Wales, photographed in 1882. Alexandra was famous for her beauty, which lasted all her long life, but her physical attractions were not enough to keep her husband faithful or virtuous.

This did not mean he was out of trouble. Bertie was never out of trouble. Six years later, he had another lucky escape. In 1876, the Earl of Aylesford sued his wife for divorce. Bertie was not named as co-respondent this time. The man named by the earl was Lord Blandford, heir to the Duke of Marlborough. But Bertie had written letters to the Countess of Aylesford. Read a certain way, some suggested a very close, maybe sexual, relationship.

Unfortunately for Bertie, Lord Blandford had a fiery younger brother, Lord Randolph Churchill. When Lord Randolph worked himself into a temper, sparks flew. Randolph threatened to publish Bertie’s letters. But then the Duke of Marlborough stepped in and put a stop to the divorce proceedings. It had been a narrow escape.

By now, there was talk that Bertie was not fit to succeed his mother on the throne. That faded after a while. But in 1890, Bertie added fuel to the fire once again. In September that year, the prince was staying at Tranby Croft, country home of his rich friend Arthur Wilson and his wife.

On September 8, after dinner, it was decided to play a round or two of baccarat, the card game. Baccarat was illegal in England at the time. Even so, bets were placed, and the game commenced.

One of the players was Sir William Gordon Cumming, a distinguished army officer with many medals to his name. Cumming had been a friend of Bertie’s for 20 years. They shared interests in womanizing and gambling.

During the evening, other players thought they had seen Cumming cheating. At that time, cheating at cards was one of the worst social crimes possible to commit. It was made even worse because the prince was there. Bertie was told what had happened.

First thoughts were to protect him from a ‘horrible scandal’. Two courtiers had accompanied Bertie to Tranby Croft. One, Major Owen Williams, thought of a way out. Gordon Cumming had to sign a document saying he would never play cards again. It made him sound guilty. But that could not be helped.

Gordon Cumming signed the document, but under fierce protest. He claimed he was innocent. But he was assured nothing more would be said on the matter. He had to be content with that.

But the story got out. Late in 1890, Gordon Cumming received an anonymous letter from Paris. This revealed that far from being hidden, gossips were having a field day talking about the ‘baccarat scandal’. No one ever found who had talked. But Gordon Cumming was furious. He decided to clear his name through the courts. He would demand that his hosts at Tranby Croft, the Wilsons, withdraw the accusation of cheating. Otherwise, he would sue them for slander.

The case was to be heard in English civil court. This meant Bertie could be subpoenaed as a witness. For a member of the royal family to appear in a witness box was unheard of. It was a scandal in itself. Desperate attempts were made to persuade Gordon Cumming to withdraw the case. But he refused.

The case opened at the Chief Justice’s Court in London on June 1, 1891. Press and public were packed tightly in galleries above the courtroom. Bertie entered the witness box on the second day of the trial. Other witnesses, including Gordon Cumming himself, had been mercilessly cross-examined by prosecution lawyers. But they went gently when it came to Bertie. They did not try to pin him down, but attempted to gather his evidence as quickly as they could.

But there was one man on the jury, Goddard Clarke, who was not prepared to pussyfoot around. He stopped Bertie just as he was leaving the witness box. In a sharp cockney voice, he asked the prince questions the lawyers had avoided.

The Baccarat or Tranby Croft Scandal, in which Bertie was involved in 1890, shocked society both because his friend Cumming was accused of cheating and because baccarat was illegal. It hardly reflected well on the prince’s probity.

Had the Prince actually seen Gordon Cumming cheating at cards?

‘No,’ the Prince replied.

‘What was your Royal Highness’ opinion… about the charges of cheating made against Gordon Cumming?’ Goddard Clarke wanted to know.

All Bertie could say was: ‘I felt no other course was open to me but to believe what I was told’. It was a lame answer and it made him look foolish. But it turned the case against Gordon Cumming. The jury decided if the heir to the throne of England believed his friend was guilty, then he must be. Gordon Cumming lost the case. The consequences were dire.

Cumming’s social life was at an end. He was thrown out of clubs. He was banished from the British Army. No one in high society would speak to him, or of him. He might as well have been dead. And all because he had dared to involve a future king of England in a grubby court case.

But Bertie did not get away scot-free. He received much criticism from the press – for gambling, for keeping bad company, for betraying his friend, for setting a bad example.

‘If he is known to pursue in his private visits a certain round of questionable pleasures’, thundered The Times of London, ‘ the serious public…regret and resent it.’

This was mild compared to a cartoon in German newspapers ridiculing Bertie’s emblem – the tall, white, Prince of Wales feathers. The Prince of Wales’ motto was also depicted, but the inscription had been changed from ‘I Serve’ to ‘I Deal’.

The French press made the most of the scandal. They printed gossip that hinted Bertie was about to leave his mother’s court and abdicate, giving the crown to his eldest son, Prince Eddie. But what even the prying French press did not know was that Eddie on the throne of England would have been a downright disaster, for he was the royal family’s darkest, most embarrassing secret.

Born in 1864, Prince Eddie grew up idle, weak and backward. His tutors found it impossible to teach him anything. He was unable to concentrate for any length of time. And he did not give a damn. If anyone tried to discipline Eddie or give him instructions, he replied with an idiotic grin or a shrug of the shoulders.

Experts and specialists were called in. But they could not tell what was wrong. Eddie’s parents, Bertie and Alexandra, were in despair. They tried a few cures of their own. Eddie was sent to Cambridge University in the hope that somehow it would spark an interest in something. But this idea failed. One of Eddie’s tutors described him as ‘abnormally dormant’. Another remarked: ‘He hardly knows the meaning of the words "to read".

Next, Eddie was placed in the army. But his instructors soon realized he could not manage even the simplest parade ground drills. After that, Eddie became a cadet in the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, in 1877. The results were no better.

There was one last cure Eddie’s parents had not tried yet. They would find him a nice, sensible, down-to-earth wife who would act as his minder. This was the same trick Queen Victoria had used on Bertie himself. It had not worked then. But Bertie and Alexandra were so desperate by this time, they could not think of anything else to do.

The girl they chose was Princess May of Teck, a cousin of Eddie’s and a descendant of King George III. May was 25; young, but not too young. She was very disciplined and dutiful. She would make a first-class watchdog. Eddie and May became engaged on December 3, 1891. Their wedding was fixed for the following February. But it never took place. Eddie went down with influenza the day before his 28th birthday, on January 7, 1892. The following day, he only just managed to stagger downstairs to look at his birthday presents.

The Prince of Wales is pictured here in 1901, just before he succeeded to the throne. He loved the pomp and ceremony of royalty and relished wearing medals and orders, carrying his sword and wearing his plumed hat.

The aged Queen Victoria in this photograph did not appear on her postage stamps. Throughout her 63-year reign, she appeared as the pretty 21-year-old she had been in 1840, when Britain’s first stamp, the Penny Black, was issued.

From then on, his health became worse and worse. Later, Princess May remembered the scene at Eddie’s bedside. It was like some ghastly tableau. The grieving mother, Alexandra, the tormented patient, Eddie, the helpless doctor and the family watching it all over a specially erected screen. Eddie died at 9:45 A.M. on January 14 while his mother held his hand. Later, at Eddie’s funeral, Princess May’s wedding bouquet decorated his coffin.

It was all very sad. Eddie’s short life had been wasted. His parents became ill with grief over the tragedy. But it had surely crossed several minds that tragedy now was better than disaster later. Many people, including Queen Victoria, believed that if Eddie had ever become king, the English monarchy would have come to an end.

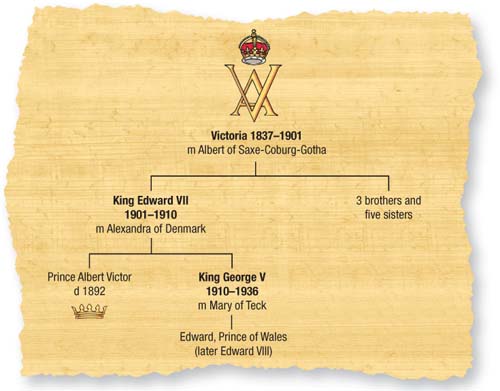

With Eddie’s death, his younger brother Prince George became their father’s heir. In 1893, George married Princess May. Eight years later, Queen Victoria, last of the Hanoverian monarchs, died. Bertie, by now almost 60, became King Edward VII, first king of the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. The name of the ruling dynasty was changed in memory of Prince Albert, who hailed from the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha in Germany.

But nothing else changed for the new king. His high-flying social life went on. He still journeyed to Biarritz every spring. He still visited the health resort of Marienbad later in the year. Then there were the shooting season in England, regular visits to the races, rounds of golf, card-playing sessions and a new royal craze – motoring.

Throughout the year Edward VII would play host at enormous banquets. The menu typically consisted of turtle soup, salmon steak, chicken, mutton, snipe stuffed with goose liver, fruits, ices, caviar and oysters. There was plenty of claret, champagne and brandy to drink. At the end of the banquet large cigars and cigarettes were passed out. King Edward himself was a very heavy smoker: he could get through twelve cigars and twenty cigarettes a day. That was in addition to heavy drinking and overeating.

The king still had his mistresses, notably the charming Mrs. Alice Keppel. As with all his affairs, Edward’s liaison with Mrs. Keppel was carefully protected by their friends. When the couple were invited to a weekend house party in the country, their hosts quietly gave them adjoining rooms. Everybody knew what was going on. But no one breathed a word.

Queen Alexandra, of course, knew all about Mrs. Keppel. She also knew that King Edward truly loved her. In 1910, the king’s long years of overeating and high living at last caught up with him. He suffered a series of heart attacks. Alexandra remained with him until he died on May 6 at 11:45 P.M.

Before his death, however, Queen Alexandra called in many of his good friends to say a last goodbye. Among them was Mrs. Keppel. Alexandra knew how to be generous.

Edward VII loved the theatre. Here he is in the front row of the audience, sitting between his mistress Mrs. Keppel and the Duchess of Devonshire at a theatrical event at Chatsworth, the Devonshires’ country mansion.

Edward was succeeded by Prince George, who became King George V. Princess May became known as Queen Mary. King George began as the second monarch of the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, but the name would be changed again, in 1917.

The world war with Germany and its allies was being fought at the time. Horrific tales of slaughter were coming back from the battlefields in France. In England, this caused such hatred of Germany that it became embarrassing for members of the royal family to have German names and titles. So George V changed the family’s name again – to Windsor, after the royal castle in Berkshire.

King George was the opposite of his father. He was very shy and did not like the high life. He was utterly devoted to Queen Mary, so much so that if he didn’t see her for a while he felt physically ill. He took no mistresses.

Although he had loved his father, Edward VII, George had strongly disapproved of his way of life. Like the young King George III before him, he was determined to wipe out the disreputable image of the king as playboy and make the royal family respectable once again.

But like George III, his plans went haywire. The culprit was exactly the same; the heir to the throne. George V’s eldest son and heir, Prince Edward, was arguably worse than all the other troublesome heirs put together. He very nearly destroyed the monarchy.

King George V and Queen Mary in full coronation robes. George V, who succeeded his elder brother Eddie as their father’s heir in 1892, came to the throne after the death of Edward VII on May 6, 1910.

King Edward VIII came to the throne determined to make Wallis Simpson his queen. He met stern, unyielding opposition that ultimately forced him to abdicate.