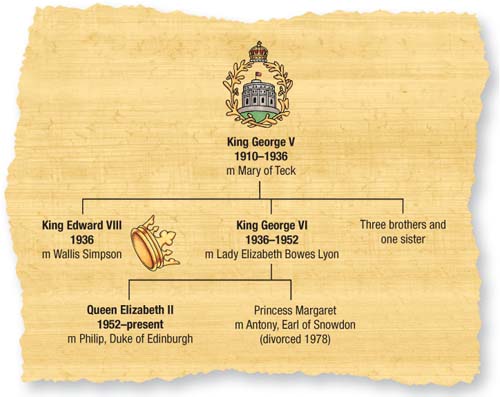

Quarrels between monarchs of England and their eldest sons had been going on for almost two centuries when King George V came to the throne in 1910. George and his son and heir, Prince Edward, would carry on in the same way.

![]()

But their quarrel was much more serious than any before. So grave, so fundamental was this particular dispute that the royal family themselves believed they were finished.

Essentially, the problem with Prince Edward – known as David within the royal family – was that he did not wish to be a prince. He wanted nothing to do with the pomp and pageantry that went with being royal. Royal duties bored him. He hated formality. He hated privilege. What he wanted was to be ordinary, something no royal could ever hope to be.

All this set David on a collision course with his parents, King George V and Queen Mary. Their devotion to duty was total. If it meant making personal sacrifices – lack of privacy, limited choice of friends – that was too bad. Rules had to be obeyed.

David, of course, wanted to toss out royal rules. The first public sign of how he felt came in 1911. That year, aged 16, he was invested Prince of Wales at a grand ceremony at Caernarvon Castle in Wales. Photographs of the event show him looking sulky and glum. Later on, David did everything he could to test the limits placed upon him by royal birth. During World War I he insisted on going to France and the front line of the fighting. Everyone was horrified. Suppose David were taken prisoner by the enemy? Suppose he were killed? It would not do. The heir to the throne had to be protected.

Glum-looking Prince Edward, known as David, is seen here with his parents, King George V and Queen Mary at his investiture as Prince of Wales at Caernarvon Castle in 1911. He later referred to the robes as a ‘preposterous rig’.

David would have none of it. He went to France. He went right to the front line. And he was there, in the trenches, while British soldiers were under fire.

‘The prince is always in the thick of it,’ one soldier wrote home to England. ‘ Only last night he passed me when the German shells were coming over.’

Despite the dangers and risks, David loved every minute of it. At last, he could be with ordinary men, sharing their problems, talking with them as if he were their equal. The king definitely did not approve. He believed royals should remain aloof and dignified. He told David: ‘The war has made it possible for you to mix with all manner of people. But don’t think this means you can act like other people. You must always remember… who you are.’

The king was already too late. In 1918 David had taken refuge in an air-raid shelter in London while German Zeppelins were dropping bombs. There, he met a young married woman, Freda Dudley Ward. David fell madly in love with her. Within a short while, they were all but living together.

For a prince to have a mistress was, of course, nothing new. But Freda Dudley Ward was David’s entree to the sort of social life where he at last felt at home. It was not the stiff, starchy circle of ‘good’ families approved by his parents. It was the so-called ‘demi-monde’, the ‘twilight’ world of wild all-night parties, fashionable nightclubs, loose morals and shady people. They included social climbers, gold diggers and profiteer millionaires. These were not the sort, according to the king, that his son should have had anything to do with.

David’s parents tried to ’cure’ him by sending him on overseas tours, but the cure never worked. On his return to England David simply took up again where he had left off. He was back at the parties and nightclubs almost as soon as he got off the ship.

After a while, David took on another mistress, a beautiful American, Thelma, Lady Furness, a sister of Gloria Vanderbilt. Thelma, too, had a large circle of fun-loving friends. In 1931, she introduced David to two of them, Wallis Simpson and her second husband, Ernest.

At first, the Simpsons were just two more of David’s acquaintances. But in 1934, Thelma had to return to the United States. She left ‘the Little Man’, as she called David, in the care of Wallis Simpson. It seemed a safe bet. Wallis was plain, scrawny and a little sour-faced. Thelma reckoned she was no competition.

David, seen here in army uniform, relished the chance to mix with ordinary young soldiers in the trenches of World War I. He longed above all to be ordinary himself, but his royal birth made that impossible.

During Edward VIII’s brief reign as king, only one set of stamps was issued for Great Britain, including this one.

Little did she know. While Thelma was away, David fell in love with Wallis. She was more womanly, more protective and a much stronger character than his other women. At a time when England was hard hit by the Depression, she shared David’s concern for the plight of ordinary people.

‘Wallis,’ David told her, ‘you’re the only woman who’s ever been interested in my job!’ She was just what David wanted.

But Wallis Simpson was just what David’s parents did not want. It was not because she was American, it was because she was a divorced woman and, as David’s passion for her grew, was likely to be divorced again. At this time, divorce was considered immoral in England. Members of the royal family were not supposed to know or even speak to anyone who had gone through a divorce.

Now here was the heir to throne involved in a romance with a divorced woman while she was still married to her second husband. The shock was tremendous. But Wallis was no passing fancy. Edward wanted to marry her and make her his queen.

King George and Queen Mary were helpless. They forbade David to bring Wallis to the royal palace. David thought his father was a stuffy old prig. The king thought his son was a cad. Queen Mary thought Wallis an ‘adventuress’. This seemed to be a general opinion about Wallis, who was branded a fortune hunter and a loose woman out to get as much as she could grab from her royal connection. The British secret services, who kept Edward and Wallis under close surveillance, certainly thought so. Early in 2003, their reports were made public for the first time, and revealed that Wallis was very careful to feed Edward’s infatuation for her. She kept secret from both the prince and her husband, Ernest Simpson, that she was having an illicit affair with a car sales-man named Guy Trundle, and fended off all other women who might get near her royal lover. Meanwhile, the public in England knew nothing of the growing royal crisis. There was no television. Cinema newsreels were carefully censored, so too were radio broadcasts. Few people took holidays abroad, where the foreign press was full of the story. By general agreement, newspapers in England kept quiet about the whole affair. But sooner or later, the truth was bound to come out.

On January 20, 1936, King George V died. David, the queen and other members of the royal family were at his bedside. Queen Mary curtsied to her son, in recognition of him as the new king, Edward VIII. But she could not help remembering what her husband had once said: ‘The boy will ruin himself within the year’. How right he was.

Now he could show Wallis off to everyone, and the way he did it was outrageous. In May 1936, when he hired a yacht, the Nahlin, for a cruise in the eastern Mediterranean, he and Wallis were accompanied by several of their ‘unsuitable’ friends. What happened next filled the foreign newspapers with smut and scandal for many weeks. The Nahlin’s passengers, including the king, arrived at various ports of call drunk and barely dressed. They gave noisy parties on board the yacht. King Edward and Wallis did not care who saw them kissing and cuddling. All of it was considered a grossly undignified way for the King of England to behave.

This illustration of Wallis Simpson flatters her. The British public found it almost impossible to understand how the sour-faced, middle-aged woman pictured in their newspapers could rock the throne of England and the royal family.

According to royal officials, this was not how the King of England should appear in photographs: a bare-chested King Edward VIII is pictured with Wallis Simpson during the cruise of the yacht Nahlin in the Mediterranean.

The king could not have cared less. What he wanted to do, he did – and damn what anyone else thought.

‘To oppose him over doing anything,’ Queen Mary wrote, ‘is only to make him more determined to do it. At present, he is utterly infatuated (with Mrs. Simpson), but my great hope is that violent infatuations usually wear off.’

It did not wear off. In July 1936, while the king and Wallis were still cruising on board the Nahlin, her divorce proceeding was already underway. The case was due to be heard in court on October 27. Simple arithmetic was all that was needed to guess what was in King Edward’s mind. The divorce would be final in six months, on April 27, 1937. The king’s coronation was fixed for May 12. There was just enough time for Edward and Wallis to get married and be crowned king and queen soon thereafter.

The royal scandal became a serious national crisis. Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin was called in. He tried to persuade the king to give up Mrs. Simpson. He failed. The king’s own relatives tried. They failed. So did the Archbishop of Canterbury. And the governments of the Dominion countries of the British Commonwealth – Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa – all failed.

By early December, King Edward VIII had become a man none of his friends wanted to know anymore. They realized the biggest royal scandal of the century was about to break and did not want to be involved. Suddenly the king’s friends started turning down invitations to Fort Belvedere, his personal home. They made excuses not to attend parties, or go on royal picnics. They had never liked Wallis Simpson, they said. As for the king, they thought he must be crazy.

This is the abdication document signed by Edward VIII on December 10, 1936. Edward signed himself ‘RI’: Rex Imperator (King Emperor), but it would be for the last time. His three brothers, Albert, Henry and George, signed the document as witnesses.

All this happened within a few days. The English poet Osbert Sitwell dubbed it ‘Rat Week’. But as the rats deserted the ship, the ship was sinking. When the silence of the English newspapers was broken on December 3, the king was on his own. The next day, Wallis fled for safety to France after stones were thrown at the windows of her home in London. From there, she begged the king to let her go rather than give up his throne for her sake.

He would not even think of it. ‘No matter where you go,’ he told Wallis, ‘I will follow you!’

What Edward VIII wanted was the throne of England and Wallis, but if he had to choose between them, then the throne would have to go. The throne went on December 10, 1936 when Edward VIII became the first king of England to abdicate of his own free will.

His decision caused anguish in the royal family. The heir to the throne, Edward’s younger brother Bertie, became terrified at the thought that now he would be king. He burst into tears and sobbed on his mother’s shoulder. His wife, Elizabeth – the late Queen Mother – said, ‘It was like sitting on the edge of a volcano.’

Bertie had never been trained to be king. He was nervous. His health was poor. He suffered from a stammer. Appearing in public was agony for him. He had a nice, quiet life with his lovely wife and two daughters, Elizabeth and Margaret. Now all that was to end. No wonder Bertie was so upset.

The former king crossed the English Channel into lifelong exile on the night of his abdication. On June 3, 1937, he married Wallis Simpson at a château in northern France. No member of the royal family was there. The couple were given new titles – Duke and Duchess of Windsor. But there was one thing they did not get. Bertie, who took the name King George VI, refused to make Wallis a ‘Royal Highness’. He reasoned that, with two failed marriages behind her, the chances of the third one lasting weren’t all that good.

Edward and Wallis never forgave King George or his family. Although Edward had no authority to do so, he himself gave Wallis the title which King George had kept from her. He insisted that everyone address his wife as ‘Her Royal Highness, the Duchess of Windsor’.

Back in England the duke was offered the governor-ship of the Bahama Islands. The position carried little prestige. The Bahamas were the most insignificant colony in the whole British Empire. Usually, its governor was a minor civil servant or a retired army officer. But the islands had one great advantage: they were well away from the war zone. It was a good place to park the Windsors for as long as the war lasted.

Once in the Bahamas, the Duke of Windsor still could not stay out of trouble. The worst thing that happened while he was governor was the murder of Sir Harry Oakes, a mining millionaire. Oakes was a shady character. He lived in the Bahamas to avoid paying taxes and had secret arms dealers for friends.

In 1943, Sir Harry was savagely murdered. The duke personally took charge of the investigation. He had no experience in such matters. As a result, he bungled the case so badly that an innocent man – Oakes’ son-in-law – was framed for the crime. Fortunately, he was found not guilty at his trial. The real killer was never discovered. But there were hints about Mafia involvement in the affair.

Ever since his abdication, the duke had wanted to serve his country in a ‘top job’. But yet again, he had become embroiled in scandal. The sordid business of Oakes and his kind had rubbed off a little on him. Beside this, he had proven himself incompetent. The mess he made of the Oakes affair made sure that the duke was never offered an official post again.

After the end of the war in 1945, the Windsors returned to Europe. Still shut out by the royal family, there was only one place for them to go. They became stars of the rich, well-heeled social scene. They moved from one fashionable resort to the next – Biarritz, Venice. They dined at Maxim’s, the famous Paris restaurant, twice a week. Photographs of them enjoying themselves in nightclubs and luxury hotels appeared in newspapers. They lived the high life to the fullest.

As Duke and Duchess of Windsor, David and Wallis concentrated on an energetic social life, appearing in all the ‘right’ fashionable places in the ‘right’ fashionable company. Here they are following the play at a golf tournament.

But it all came to an end in 1972, when the duke died in Paris. After that, if anyone still thought of Wallis as a greedy gold digger, out for all she could get, they were proven wrong. For a time, she refused to admit that the duke was dead and had to be forcibly removed from his bedside.

‘He was my entire life,’ she said at her husband’s funeral at Windsor.

‘He gave up so much for me. I can’t begin to think what I shall do without him.’

She could not do without him. Wallis was never able to put her life back together again. She would sit alone for hours in the duke’s room, which was kept exactly as it was when he died. ‘Goodnight, David!’ she would say before going to bed.

Wallis went into a steady decline. She ended up paralyzed and crippled. She spent her last years lying in bed surrounded by pictures of herself and her husband. She lived in the past, dreaming of the years they had spent together. Wallis died in 1986, aged 89. She was buried next to Edward at Windsor. Queen Elizabeth II and her family attended the ceremony.

The duke had always wanted Wallis to be accepted into the royal family. In death, she had managed it at last. But there was still no official ‘HRH’ title. The plate on her coffin read simply ‘Wallis, Duchess of Windsor 1896–1986’.

King George VI had died 20 years before his elder brother, in 1952. The good name of the English royal family had taken a frightful battering in the abdication crisis of 1936. The royals themselves believed they wre finished. But in his reign of 15 years, King George and his admirable Queen Elizabeth had done a first-class repair job. The royal family became respectable once again. This time there was no troublesome heir to ruin the effort. The love and affection King George felt for his heir, Princess Elizabeth, was so great that his eyes filled with tears whenever he spoke of her. The long series of royal quarrels was over.

The Windsors’ nightlife was avidly followed by the press. The duchess was of particular interest to newspaper readers. She was usually wearing magnificent jewels from the collection showered on her by the duke.

This did not mean that Elizabeth II was going to escape trouble and scandal. Trouble made its appearance very early on, on the day of Elizabeth’s coronation, June 2, 1953. That same day, outside Westminster Abbey, her younger sister Margaret was caught on camera picking a piece of fluff off the uniform of Group Captain Peter Townsend of the Royal Air Force. It seemed the sort of thing a woman did when she regarded a man as ‘hers’.

Townsend was a royal servant, a former wartime fighter pilot and an equerry to the new queen. Beady-eyed journalists watched the scene and took note. A new royal romance was in the air. But so was a new scandal. Peter Townsend was a divorced man and an untitled commoner. By the royal rules of the time he had no business romancing the sister of a queen.

The perfect royal family. George VI and Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) with their daughters, Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret. This picture of domestic bliss was in total contrast to the high jinks of the duke and duchess.

February 24, 1981 was the day that years of royal wedding speculation ended. Charles, Prince of Wales announced his engagement to the pretty 19-year-old Lady Diana Spencer.