Princess Margaret was the live wire of the royal family. If she had not been born a princess, she could have had a brilliant career on the stage – as a mimic, singer or pianist.

![]()

She had charm, she had zest. She had personality. And, as Peter Townsend himself said, she was ‘intensely’ beautiful. What Margaret did not have was luck.

Margaret first met Peter Townsend in 1945, when she was 15. He had just become equerry to her father, King George VI. Townsend was handsome and charming. He was a war hero. Margaret fell deeply in love with Peter Townsend and set her heart on marrying him.

Margaret was delighted when she found that Townsend loved her in return. But they faced tremendous obstacles. Townsend was divorced. The social barriers divorced people faced were bad enough. But the English church did not even recognize divorce. It was an impossible idea that the queen’s sister should marry a man whose first wife was still living, and become stepmother to his children.

The queen, supreme head of the Church of England, could not possibly give permission for such a marriage. The only way it could go ahead was for Margaret to give up her royal title, cut herself off from her family, and leave England to live abroad for the rest of her life.

Peter Townsend and Princess Margaret were often photographed together during royal engagements. But their romance was doomed from the start. It was not yet acceptable for royals to marry commoners.

Queen Elizabeth did not want that to happen to her beloved sister. So she tried another way. Peter Townsend was given a job in Belgium. It was only just across the English Channel, but far enough away to separate him from Margaret. The queen hoped their love would cool. That did not happen. When Townsend returned to England in 1955, the romance was still very much ‘on’.

English newspapers went into a frenzy of speculation. Would the couple marry or not? ‘Come on, Margaret, make up your mind!’, ran one newspaper headline.

But Margaret was not in a position to make up her mind. She was bombarded with reasons not to marry Townsend. The church was against it. The royal family did not like it. The people were divided. Some thought that as a war hero, Townsend would make an admirable husband for a royal princess. Others believed that Margaret should put her royal duty first.

Royal duty won in the end. The announcement came on October 31, 1955. Margaret had decided not to marry Peter Townsend.

‘Mindful of the Church’s teaching that Christian marriage is indissoluble, and of my duty [to the queen], I have decided to put these considerations before all others.’

It was the worst moment of Margaret’s life. She never got over it. She plunged into a frantic round of parties. She became the star of the fun-loving jet set. She went to nightclubs. She shocked everyone by drinking and smoking in public. She made friends with people royals were not supposed to mix with – actors, actresses and pop stars.

Then, in 1959, Townsend wrote to Margaret that he was going to marry a Belgian girl, Marie-Luce. No one was surprised that Marie-Luce looked almost exactly like Princess Margaret. Margaret, meanwhile, had received a proposal of marriage from the English society photographer, Antony Armstrong-Jones.

‘I received the letter from Peter in the morning,’ she said later, ‘and that evening, I decided to marry Tony. I didn’t really want to marry at all. Why did I? Because he asked me!’

In time, the reason proved not to be good enough. Margaret and Tony, as they came to be known, were married at Westminster Abbey on May 6, 1960. It was a splendid royal occasion. The couple later had two children, but the marriage was doomed. Armstrong-Jones, who became Lord Snowdon, came to hate his link with the royal family. It got in the way of his career. The couple had terrible rows. Each took lovers. At last, in 1976, they decided to give up. Margaret and Tony separated and in 1978 they were divorced.

Margaret never married again. She drank and smoked even more than before. She took much younger men as lovers. She held high-life parties at her villa on the island of Mustique.

At home in England, Margaret received occasional visits from Peter Townsend. But he died in 1995. At last, it all caught up with her. Her health began to fail. She suffered a series of strokes. Outside her family and friends, no one knew how badly she was affected until August 4, 2001, the day her mother, the Queen Mother, celebrated her 101st birthday. There was the Queen Mother, looking fit and sprightly, waving to crowds cheering her outside her London home, Clarence House. And there was Princess Margaret, sitting in a wheelchair, half-paralyzed and partially blind. Princess Margaret died six months later, on February 9, 2002, at the age of 71.

Margaret never got over the Townsend affair, though her marriage to photographer Antony Armstrong-Jones in 1960 concealed that fact. Ironically, Margaret became the first of the Windsors to divorce when that marriage ended in 1978.

By that time, the royal family had been rocked by another scandal even greater than the Townsend affair, and almost as serious as the abdication of King Edward VIII. It was a story of betrayal, bad faith and hole-in-the-wall affairs. Once again, people wondered if the English monarchy would survive. Once again, they watched with a mixture of horror and fascination as the fearful story unfolded.

This, though, was the last thing on anyone’s mind on July 29, 1981, when Prince Charles, heir to the throne, married Lady Diana Spencer at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. The press pronounced it the ‘fairytale’ marriage of the century. The fresh-faced 20-year-old Diana became an overnight star. Everywhere she went, she was greeted by huge crowds. She was the most famous, most photographed woman in the world. The public loved her. The press loved her. Everyone loved her. Except for her husband, Prince Charles.

After the end of the Townsend affair, Princess Margaret indulged in the high life. Her excessive smoking and drinking produced serious health scares and she was accused, quite unjustifiably, of neglecting her royal duties.

The kiss on the balcony at Buckingham Palace, the romantic climax to the ‘fairytale wedding’ of the Prince and Princess of Wales. The marriage, however, was no fairytale: for the Windsors, it marked an era of unprecedented scandal.

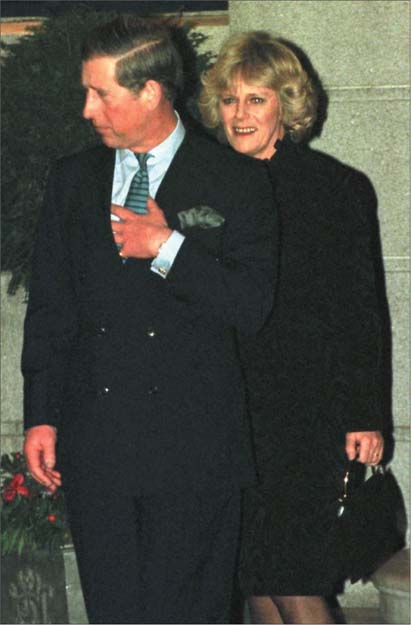

No one knew it at the time, but Charles was in love with someone else: Mrs. Camilla Parker-Bowles, who had once been his girlfriend. Charles could have married Camilla as far back as 1973. But he had thought she was not quite ‘pure’ enough for a future queen of England. She had had lovers. She was too much of a ‘go-getter’ to settle down to the dull round of royal duties. So Charles let her go and Camilla married someone else. Even then, Camilla was not completely out of Charles’s life. They remained friends and occasional lovers. Camilla boosted Charles’s confidence, made him feel good and accepted him as he was. Before long, Charles realised that by marrying Diana, he had married trouble.

Lady Diana Spencer, youngest daughter of Earl Spencer, was the child of a broken marriage. When she was only six, her mother, Frances, suddenly disappeared from home and never came back. The divorce that followed was so brutal that Frances would never speak about it. In a fight for custody of their four children, Earl Spencer won by blackening his wife’s character. The effect on Diana and her younger brother, Charles, was devastating.

Diana grew up insecure and longing for love. She wanted a husband who would be hers and hers alone, who would love her and protect her, and always be there for her. But Charles could not give Diana the attention she craved. Being Prince of Wales was not a nine-to-five job. Like other members of the royal family, Charles had royal duties to perform and was often away from home.

Moreover, Charles and Diana were very different people. Charles loved opera. Diana preferred pop music. Charles liked reading books about philosophy or history. Diana read romantic novels. None of this would have mattered had there been enough goodwill between them. But goodwill was difficult when Charles’ friends thought Diana was ‘an airhead’. Her friends thought Charles was stuffy and dull.

It did not take long for relations between Charles and Diana to become strained. Diana came to believe that if only she could get Charles away from Camilla, everything would be all right. But the more Diana nagged him to give up Camilla, the more Charles clung to Camilla.

Diana staged dramatic tantrums. While she was expecting their first child, Prince William, Diana threw herself downstairs to prevent Charles from going out riding.

Unfortunately, Charles was not the sort of strong-minded man to cope with a wife who behaved like this. Charles’s solution was to run to Camilla, which only made matters worse. Royal duty demanded that, in public, Charles and Diana must put a brave face on the situation. Even so, there was plenty of media speculation that all was not well in the household of the Prince and Princess of Wales. It was easy to laugh off the talk as gossip, but in fact, the media were right. By 1986 Charles and Diana’s marriage was crumbling fast. Charles later confessed that by that time he was no longer sleeping with his wife. In 1987 Diana seemed to give up hope that Charles would ever give her the attention she wanted. She began to look for it elsewhere, with other men.

In 1991 came the tenth anniversary of Charles and Diana’s wedding. A date to celebrate? No, it was not. No one felt like celebrating. On their wedding anniversary, they were apart, Charles in London, Diana in Wales. The tenth anniversary party Queen Elizabeth wanted to give for them never took place.

Meanwhile a time bomb was ticking that would burst the bubble of the so-called ‘fairytale’ marriage forever. Sometime in the winter of 1991/2, Diana gave the royal reporter Andrew Morton long, detailed interviews about what was really going on in her marriage. She told him everything. No holds were barred. Morton’s book Diana: Her True Story was published in London on June 7, 1992. It was a bombshell. Morton painted a picture of Charles as cold and arrogant. He was supposedly jealous of Diana’s success and popularity.

Even worse was to come. Diana: Her True Story revealed that Diana had attempted to commit suicide five times. She suffered from the eating disorder bulimia. She had mutilated herself on several occasions.

When Morton’s book was published, there were denials all around that Diana had had anything to do with it. But who else could have known about the marriage in such detail? Morton’s fellow journalists and others with inside information guessed the truth, but the public was unaware for another five years, until shortly after Diana’s death.

Public reaction to Diana: Her True Story was extraordinary. Many readers were convinced it told the truth. If Diana had taken lovers – which she had – Charles’s behaviour had driven her to it. Nothing seemed to be too bad to say about Prince Charles, who was now cast as Public Enemy Number One.

But even this was not the end of the scandals of 1992, which Queen Elizabeth later described as her annus horribilis – horrible year. On March 19, the queen’s second son, Prince Andrew, Duke of York, separated from his wife, Sarah Ferguson. They had married in 1986, but the marriage soon degenerated into a terrible tale of neglect, irresponsibility and adultery. Then, on April 13, the queen’s only daughter, Princess Anne, began a divorce action against her husband, Captain Mark Phillips. With that, the marriages of three of the queen’s four children were on the rocks.

But the main spotlight was on Charles and Diana. Diana: Her True Story had been the end of the line. There could be no forgiveness. Prince Charles felt grossly betrayed. The queen was angry at all the dirty linen Diana had washed in public.

Charles’s friends responded to Morton’s book in a magazine article written by the journalist Penny Junor. This told the prince’s side of the story. It pictured Diana as paranoid and jealous. She had kept Prince William and Prince Harry away from their father. She swore at Charles and pulled every dirty trick known in the annals of shrewish wives.

By this time, the media were daily reporting accusation and counter-accusation, claim and counter-claim. No one knew any longer who was telling the truth and who was lying. Scandalous revelations came thick and fast. Smutty conversations on secret tapes, involving both Charles and Diana, were transcribed and published. The headlines were lurid. ‘My Life of Torture’, ‘Love Tapes Upset Diana’, and worse.

‘Camilla,’ Diana said, ‘was always there.’ Mrs. Camilla Parker-Bowles had been an important presence in Charles’s life since 1973, and their relationship continued even after his marriage to Diana.

Diana, Her True Story by Andrew Morton first appeared in 1992. After Diana’s death in Paris in 1997, the book was re-published and the fact, formerly denied, that she had fully cooperated with Morton became public knowledge.

After all this it was impossible for the ‘fairytale’ marriage to go on. The end came near the close of 1992. On December 9, Charles and Diana’s separation was announced in the House of Commons by Prime Minister John Major. The divorce followed nearly four years later, on August 28, 1996.

Now that Diana was no longer royal, she lost her title of ‘Her Royal Highness’ and no one had to curtsey to her any more. But she was still a headline-maker and was going to make more sensational news after July 1997, when she received an invitation from the Egyptian billionaire Mohamed Al Fayed, owner of Harrod’s, the luxury London store. Al Fayed offered Diana and her two boys his villa at St. Tropez, complete with his yacht, Jonikal, and a companion, his handsome and personable son Dodi.

No sooner had Dodi and Diana got together in St. Tropez than the press was weaving a romance about them. Sensing a major story, boatloads of newsmen and photographers descended on St. Tropez. Dodi and Diana fled, first to the Mediterranean island of Corsica, then to Sardinia and finally, on 30 August, to Paris. But word of their arrival had gone ahead of them and the paparazzi, who made a living taking and selling photographs of celebrities, were waiting for them. Dodi and Diana were the greatest celebrities the paparazzi had encountered in a long time. A group of them followed the couple to their Paris hotel, and then laid siege to it. The couple managed to escape by a back entrance, but the paparazzi were soon on their tail.

It was nearly midnight. Dodi ordered his driver, Henri Paul, to step on it and a high-speed chase began through the streets of Paris. As Henri Paul reached an underpass close to the Place d’Alma, his Mercedes was doing close to 135 miles per hour. The Mercedes shot into the under-pass. Soon Henri Paul, who, according to reports, was drunk, lost control of the car. It skidded across the tunnel, crashed into a pillar, bounced off and hit the opposite wall. The car ended up a tangle of twisted metal and broken glass.

Dodi was killed at once. So was Henri Paul. Diana lived through the crash, but her injuries were too severe for her to survive. She was pronounced dead at the hospital at 4:00 A.M. the next morning. She was 36.

When the news reached Britain, people went into shock. They stood in the streets, tears pouring down their cheeks. Thousands descended on London, and laid so many flowers for remembrance outside the royal palaces that the sidewalks disappeared under a thick carpet of blooms. Many of the mourners stood in line for hours to sign books of condolence. There was open criticism of the ‘cold-hearted’ Queen and her family who were spending their regular holiday at Balmoral in Scotland and were still there, instead of heading immediately for the capital.

Eventually, the royals gave in. They returned to London and the Queen gave a short tribute to Diana on television. For her pains, members of the public pronounced her speech ‘not emotional enough’.

Queen Elizabeth suffered appalling embarrassment over the revelations contained in Andrew Morton’s book. In it, she was pictured as aloof and unhelpful toward her daughter-in-law, the Princess of Wales, although in fact the opposite was true.

Diana’s funeral took place on September 6. London virtually closed down for the day. Huge crowds lined the streets as Diana’s coffin was driven to Westminster Abbey for a short service. They were still there when the cortège made its way out of London heading for Northamptonshire and Diana’s childhood home. Althorp House. There, in a private family ceremony, she was buried on an island in the middle of a lake.

‘Goodbye, England’s rose,’ said the next day’s headlines as newspapers were filled, page after page, with reports of one of the most emotional, most tear-filled days England had ever seen.

But this was by no means the end of the Diana story. The intrusive, gossip-hungry media soon saw to that. Charles and his long-time love Camilla Parker-Bowles were still around and therefore still susceptible to reports that Diana’s army of fans had never, and would never, forgive the Prince for the way he had treated his wife.

Even six years after Diana’s death, millions were still willing to feed on any ‘news’ that painted the Prince as a villain. In January 2004, for example, a newspaper report appeared about a letter purportedly written by Diana. In this, she stated that Charles was planning a car accident in which she would suffer ‘a serious head injury’. The letter was later revealed as a crude forgery, but not before it had convinced millions that Charles was a potential murderer.

The public were regularly polled for their opinions, and these showed that a majority rejected Charles as their future king. They preferred his son William as heir to the throne instead.

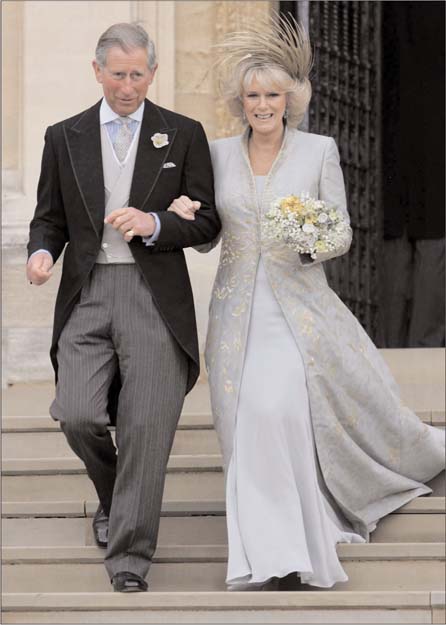

Over seven years after Diana’s death, when Charles at last married Camilla Parker-Bowles on 9 April 2005, the numbers who wanted William for king had dropped, but still stood at 42 percent, 8 percent higher than in 2001.

Diana’s continuing influence was evident from the moment Charles and Camilla became engaged on 10 February 2005. It was announced that instead of being called ‘Princess of Wales’ after the marriage, Camilla would take her future title, HRH the Duchess of Cornwall, from Charles’s estate, the Duchy of Cornwall. She would not be Queen when he became King, but ‘Princess Consort’.

These efforts to avoid comparisons with Diana did not prevent the late Princess’s fans from sending hundreds of pieces of hate mail to Camilla before the wedding. It was feared that on the day there might be demonstrations against the newlyweds outside the Registry Office in Windsor, Berkshire, where the ceremony was performed. Consequently, Charles and Camilla bypassed the crowd of spectators waiting to greet them, and drove off as soon as the ceremony was over.

Charles and Camilla were by no means the only avenue through which the media kept the Diana story going. In 2002, for example, there was the sensational trial of Diana’s butler, Paul Burrell, who was accused of stealing items belonging to Diana, Charles and their two sons. The trial was stopped and Burrell acquitted after the Queen recalled a conversation in which the butler told her he was keeping safe the items he was later charged with appropriating. Rumours soon flourished that the Burrell trial had come too close to revealing evidence that might have embarrassed Her Majesty.

The marriage of Charles and Camilla was a very quiet affair compared to his state wedding to Diana in 1981. The ceremony took place a day later than originally planned, because, on 8 April, Charles had to travel to Rome to represent the Queen at the funeral of Pope John Paul II.

Prince Harry, furious at the intrusion into his private life, attacked a photographer who was trying to take his picture outside a London nightclub in October 2004. During the scuffle that followed, Harry was hit in the face by a camera.

Harold Brown, another royal butler whose trial on similar charges was also halted, refused to ‘sell his story’ to the Press. Paul Burrell had no such qualms. He became a headline celebrity with fresh revelations of royal misbehaviour. According to Burrell, Diana’s erstwhile father-in-law, Prince Philip, wrote her insulting letters, calling her a ‘harlot’ and a ‘trollop’. Philip, backed up by Rosa Monckton, Diana’s close friend, hotly denied these allegations.

The year 2002 also produced one of the most titillating of Diana stories. James Hewitt, one of her ten alleged lovers, was known to the tabloid press as a ‘Love-Rat’ for going public about their affair. A former major in a cavalry regiment of the British Army, Hewitt was forced to resign over the revelations. In 1998, Hewitt announced that he would never sell the 64 love letters Diana had written him, but four years later he was asking a massive £10 million for them. The price included some salacious titbits, including the nicknames Diana gave to their private parts and details of the sex toy she sent him while he was serving in Kuwait during the first Gulf War in 1991. Although Hewitt received offers, they fell far short of his asking price: the highest bid reached only £4 million.

Also in 2002, a rumour circulated that Hewitt, not Prince Charles, was the father of Diana’s second son, Prince Harry. There was certainly a resemblance between Hewitt and Harry, who was born on 15 September 1984. They had the same neat facial features and both of them had red hair. In September 2002, Hewitt publicly denied the rumours. Then news came to light that in 1985, the Royal Family had ordered a DNA test to prove paternity. Diana, it was said, was incensed, but the test proved that, after all, Prince Charles, not Hewitt, was Harry’s father.

By this time Prince Harry was 18, old enough for some hell-raising of his own. Harry gave the press plenty of material. He indulged in drinking while below the legal age. He smoked ‘pot’. He scuffled with a photographer outside a night club. But none of these compared with the furore that ensued in January 2005 when Harry was pictured at a fancy-dress party wearing German Army uniform – complete with an arm-band bearing the Nazi swastika.

Harry was savaged in the press for his ignorance of 20th century history, especially the history of the Holocaust in which Jews endured unspeakable sufferings under Nazi rule, and for insulting the memory of his great-grandparents, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth (the Queen Mother) who had been symbols of British defiance of the Nazis during World War II. Harry apologized, but the criticisms continued. The young Prince was accused of trivializing the evils of Nazism. A politician proclaimed that he should not be allowed to go to Sandhurst, the prestigious military academy, which he was due to attend in 2005. A furious Prince Charles ordered Harry to visit Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest of the Nazi concentration camps, where up to 4 million prisoners died between 1940 and 1945.

In time, the uproar faded from the headlines, but like all royal scandals, not from the record. And if that record is anything go by, ‘Harry the Nazi’, as one British newspaper called him, provides only the latest episode in the long tale of dark deeds, dirty doings and foolish fancies that have marked a thousand years of English royal history.