FORTY

In early January, Lee and Graham began separate, personal investigations into the president’s election fraud allegations. If there were any truth to them, there would be evidence, they concluded.

Lee received a two-page memo from the White House on Saturday, January 2, authored by legal scholar John Eastman, who was working with Trump.

Lee was shocked. He had heard nothing about alternative slates of electors.

In the arcane process set out in the Constitution, electors cast the final votes for president, as they had done on December 14. And in four days, the Senate was required to formally count those votes to certify the election.

The possibility of alternate or dueling slates would be national news. Yet there had been no such news.

For weeks, Lee knew some Trump allies in various states had been putting themselves forward as “alternate electors.” But those efforts were more of a social media campaign—an amateur push with no legal standing.

There had also been calls from Trump supporters to release electors pledged to Biden, so that they could vote for someone else. But that 11th-hour push was also complicated by the law, with most states prohibiting so-called “faithless” electors from switching their votes.

Trump adviser Stephen Miller had nonetheless stoked the possibility of a coming election upheaval. On Fox News in December, he claimed “an alternate slate of electors in the contested states is going to vote and we’re going to send those results up to Congress.”

In private, Eastman was insisting that groups of people in the states who sought to be electors should be considered as legitimate by Congress. They were organized and determined, he told others, and there was a precedent for recognizing a second slate. Hawaii had sent in two competing slates during the 1960 election, following a dispute between the Republican governor and state Democrats.

But unlike in 1960, this time there was no formal attempt to offer dueling slates gaining any traction at the state legislative level. Calls to governors for special sessions on the vote went unheeded. It was just an outcry—mostly Trump supporters in various states who wanted another group of electors recognized by Congress.

By January 2, Lee knew nothing had happened. It had all been talk, mere noise on the matter, which was rigorously spelled out in the Constitution.

“What is this?” Lee wondered as he glanced down at Eastman’s document.

Lee also knew any attempt to make the vice president the critical player in the certification would be a deliberate warping of the Constitution.

Lee had kept telling Mark Meadows and others in the White House and GOP that the vice president was a counting clerk, period. No other role. It was power concisely articulated and capped by those seven words in the 12th Amendment: “and the votes shall then be counted.”

Eastman’s two-page memo turned the standard counting process on its head. Lee was surprised it came from Eastman, a law school professor who had clerked for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

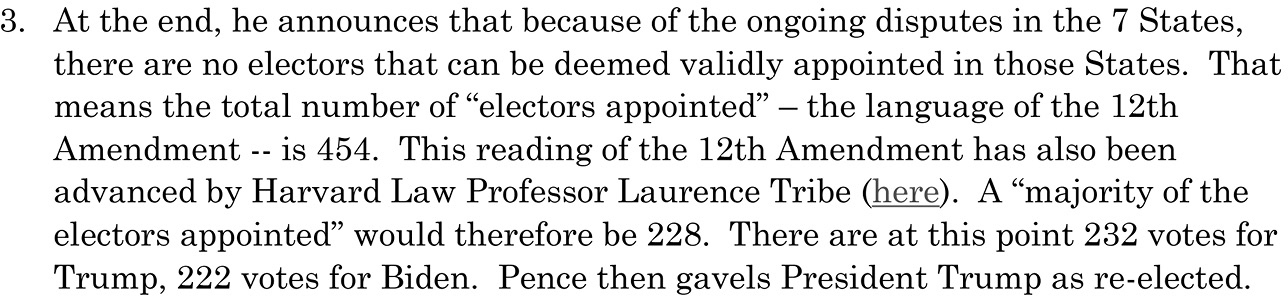

Lee read on. “Here’s the scenario we propose.” The memo set out six potential steps for the vice president. The third item jumped out at the senator.

He read it again, just to make sure. Pence “announces that because of the ongoing disputes in the 7 States, there are no electors that can be deemed validly appointed in those States.” So, Pence would cut the number of states whose votes would be counted in the election to only 43 states, leaving 454 electors left to decide who wins.

“There are at this point 232 votes for Trump, 222 votes for Biden,” Eastman wrote of such a scenario. “Pence then gavels President Trump as re-elected.”

A procedural action by the vice president to throw out tens of millions of legally cast votes and declare a new winner? Lee’s head was spinning. No such procedure existed in the Constitution, any law or past practice. Eastman apparently had drawn it out of thin air.

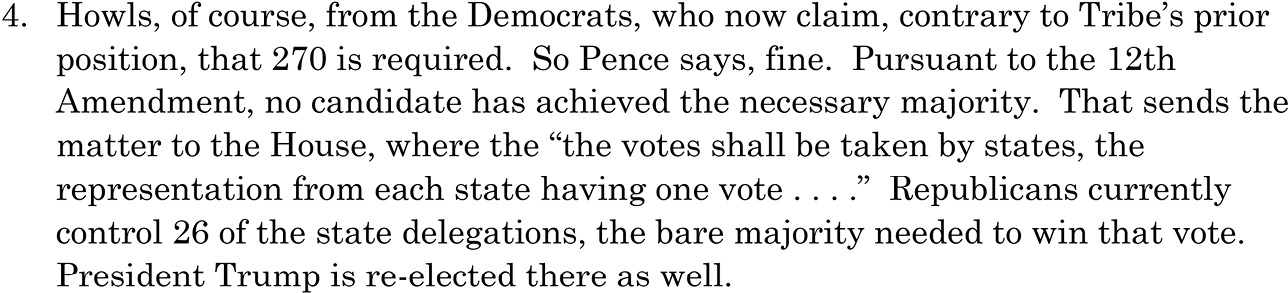

Eastman had also thought ahead to the certain outrage and worry of a coup.

That was their ballgame. Either have Pence declare Trump the winner, or make sure it is thrown to the House where Trump is guaranteed to win.

The House had decided the presidential election only twice before in American history. Lee absorbed the rest of Eastman’s memo, which also asserted “Pence should do this without asking for permission.”

“The fact is that the Constitution assigns the power to the Vice President as the ultimate arbiter,” it stated.

Nothing could be further from the truth, Lee knew. The vice president was not the “ultimate arbiter.” Like Quayle, he had memorized the line of the 12th Amendment that said the president of the Senate simply opens “all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted.”

What a mess. Lee had spent nearly two months trying to impress upon Trump and Meadows that they could pursue legal remedies, audits, recounts or other claims. They could file dozens of lawsuits. But their time was limited. “Just remember you’ve got a shot clock,” he said.

If none of that panned out, Pence only could count the votes. That was it.

Mark Meadows grew up as a self-described “fat nerd” who was an outsider. By age 61, he had slimmed down a bit to husky, and prided himself as the Trump insider. He had become the person Trump called early or late. Colleagues privately remarked how happy he was talking about calls from “POTUS,” his way of describing the president.

Meadows also worked in whispers, loving pull-asides and closed meetings. But he was not reserved. If anything, some Trump aides found him too emotional. He openly cried in the West Wing on several occasions when dealing with tricky personnel and political decisions.

Meadows called a meeting in his White House office on Saturday, January 2, so Giuliani and his team could brief Graham, in his capacity as a lawyer and chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, on the voting problems and fraud they claimed they had found.

The findings were sufficient to turn the election in Trump’s favor, Giuliani said, citing evidence that had been given to him.

Giuliani offered a computer expert who presented a mathematical formula that demonstrated the near impossibility of a Biden win. Several states had recorded more votes for Biden than previous votes for Obama in 2008 and 2012. Since polling showed that Obama had been more popular in these states, it was almost mathematically impossible for Biden to outpace Obama in raw numbers during the 2020 presidential election, Giuliani’s expert maintained.

Too abstract, Graham said. A presidential election would not be turned based on some theory. While he was suspicious of the mainstream media, which was asserting categorically that claims by Trump were false, he wanted more. Show me some hard evidence, Graham said.

Giuliani and his team said they had overwhelming, irrefutable proof of the dead, young people under the age of 18, and felons in jail voting in massive numbers.

Graham said he was sure some of this was true, but he needed proof.

“I’m a simple guy,” he said. “If you’re dead, you’re not supposed to vote. If you’re under 18, you’re not supposed to vote. If you’re in jail, you’re not supposed to vote. Let’s focus on those three things.”

Some 8,000 felons voted in Arizona, they said.

“Give me some names,” Graham asked.

They said they had 789 dead people who had voted in Georgia.

Names, Graham said. They promised to get names to him by Monday. They said they had found 66,000 individuals under the age of 18 who illegally voted in Georgia.

Do you know how hard it is to get somebody who’s 18 to vote? You’ve got 66,000 under 18 who voted, right?

Right.

“Give me some names. You need to put it in writing. You need to show me the evidence.”

They promised by Monday.

“You’re losing in the courts,” Graham said.

Trump’s lawyers had now lost nearly 60 challenges. By the end, about 90 judges, including Trump appointees, would end up ruling against Trump-backed challenges.

Vice President Pence walked into his office near the Senate chamber to meet privately with the Senate parliamentarian, Elizabeth MacDonough, late Sunday evening, January 3, after swearing in new members of the Senate.

McConnell and his chief of staff, Sharon Soderstrom, a master of policy and procedure, had encouraged Pence to do so. They did not want any surprises and believed even the scripted Pence should practice.

Sitting with his chief of staff, Marc Short, and his counsel, Greg Jacob, Pence asked MacDonough to walk him through the plan for January 6. Let me know how this will go. He took notes as MacDonough outlined how challenges could be handled and his options while presiding.

Pence peppered her with hypotheticals: What happens if this objection is made? How does this go? What are the scripts I am required to recite versus the scripts where I might have some latitude?

Short and Pence had discussed for weeks whether it was possible for Pence to avoid a made-for-TV moment announcing Trump’s defeat to the world. Instant fodder for a Pence rival in 2024.

“Can I perhaps express sympathy with some of the complaints?” Pence asked.

MacDonough was curt, professional. Stick to the script, she advised. You are a vote counter. Pence agreed.