November 1989

November 1989

November 1989

November 1989

A new roommate. A plane takes off. A plane lands. A little girl goes for a ride. And a happy coincidence.

NoRemember 3, 1989

Dear Jenny,

I just got off the phone with your mother, and she says she finally told you something, I forget what, and—what’s that? Well, how do you expect me to remember everything your mother says? Something about her jawbone growing back the wrong way, and—that’s not it? I think she also said I needn’t bother to write you a letter next week. Oh, are you getting tired of them? Well, I can’t think what else— OUCH! Why did you run your wheelchair over my foot?!

Oh, that’s right, now I remember: we’ll finally get to meet! I’m going to Sci-Con 11, and by an odd coincidence you’re going there too (I’m sure they’ll let us in, even if we’re not 11), and we can meet all the artists. They already have me jammed in with things, like autographing at Waldenbooks Saturday morning, so I probably won’t see you when you arrive, but Saturday afternoon will be open. I will want to talk to you, and sing you a song, and hold your hand—you mean you thought that was an empty threat? Ha! You’ll have just a few hours to do the whole convention, thanks to that man your mother is running the submarine over. But you should find it interesting. Then on Sunday I’ll visit you at the hospital, so I can read “Tappy” to you (provided you’re still 13), and to Kathy also if she’s interested. I gather she graduated to another ward, but you still keep in touch.

Meanwhile, it’s the usual mouse-race here. A college magazine wanted to interview me, and by the time the publisher forwarded their request, it was a day past their deadline, so I phoned them, and they interviewed me by phone from 9 to 10 last night. About the only other thing of note was a good review in PUBLISHERS WEEKLY. No, that was astonishing; they never give me good reviews, only thinly veiled sneers. Must be a new reviewer who didn’t get the word, and he’ll be fired when the chief editor finds out. I mailed out the copies of Tatham Mound, and now I’m typing Orc’s Opal—except that 22 letters piled in yesterday, after I answered 160 last month, and 10 more today. Sigh. I don’t suppose you take dictation? Only in your off hours, I’m sure. Ah, well, I have found out how to assign more functions to my computer keys, and these facilitate my letters, so I’ll just have to wrap this one up and get on into that pile of 30 letters. I don’t think I need to write you a long missive this time; I’ll save up whatever I have to tell you until next week, and save the postage. I hope you will have half an hour or so to talk to me, before the teeming masses of fans come charging in demanding your attention. Maybe I’ll hide behind your wheelchair so they won’t find me.

We started Friday morning, driving down to the Tampa Airport, and Cam (my wife) put me on the airplane to Charlotte, North Carolina. The plane left late, and I worried that it would arrive too late to make its connection, stranding me; that happened to me with buses, and I’m sure the plane companies have picked up and improved on all the old bus and train tricks. They served a snack, consisting of a ham and turkey sandwich. That’s one of the reasons I don’t like to travel: airlines hardly know what a vegetarian is. I took out the meat and ate the rest without joy; the meat would only be thrown away, so my gesture accomplished nothing. Oh, we could have ordered a vegetarian meal, ahead; but when we did that before, they gave us some kind of Oriental dish that was so fiery hot it was impossible to eat. They do have ways to make you regret making such demands. At Charlotte I found the connecting flight; it was supposed to take off from one gate, but they had changed gates and I had to go searching for the new one. That’s another reason I don’t like to travel. The plane left the terminal on time, but waited twenty minutes in the queue for the ten preceding planes to take off. It was listed as “on time” but was actually twenty minutes late, which suggests that since airlines may be penalized for running late, they find ways to conceal rather than correct their lateness. When it comes to travel paranoia, I yield to none.

I was met by Jenny’s parents, and the ten-minute drive to the hotel took an hour: the lateness of the plane had put us deep into rush hour, and the road patterning was abysmal. Why I don’t like to travel: let me count the ways …

Jenny’s folks had taken out three rooms at the Holiday Inn Executive Center, which was the convention hotel for Sci-Con 11. Two were for their use, and one for mine. They had put mine directly across the hall from theirs, but that one was the Con Suite, open and crowded all hours; I’m glad they bumped mine down the hall a bit, as I don’t think I could have slept very well in the Con Suite. As it was, my room was quiet; I never even turned on the TV set the whole time I was there. The convention folk were glad to see me; I had turned down their invitation, months ago, then changed my mind when I saw how close it was to where Jenny was. I had said I would go to the convention if Jenny did, and though Jenny was limited to one day because of a late reversal of policy by a doctor, she definitely would be there on Saturday. I met Debbie, the Con Chairman, and Cathy, programming. Along with my con badge I got a button: DEBBIE DOES SCI-CON. Well …

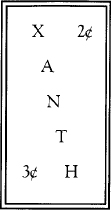

I attended the Opening Ceremony, so that the fans could see which professionals had arrived. Laurence Watt-Evans officiated, and we each said a few words. I asked folk not to take my ogre reputation too seriously: “You only need to talk with me five seconds to know that I’m no threat to you.” It happened that five artists who had worked with Xanth were attending, and Richard Pini of Elfquest also drove down from New York state at my behest: he too will be working with Xanth, setting up the graphic version of #13, Isle of View, which features Jenny Elf from the Elfquest world. Richard and I have been interested in doing a project like this since we met at the American Booksellers Association convention in Dallas in 1983, but it never quite jelled until Jenny came on the scene.

At 9 P.M. I talked with folk in the Con Suite, which was so noisy that I could not distinguish anyone’s words from more than three feet away, and was in danger of wearing out my voice before my reading came up. I was surrounded by eager fans. I can take conventions or leave them; my pride is such that I already know I can write well, even if this is news to critics, and I am not driven to hear it personally from fans. But I can survive adulation too, though I would rather be home writing my next novel. It is my policy to make myself available to fans when I go to conventions, and to avoid them at other times. I had a green ice cream sandwich there, which served for supper.

My reading was at 9:30, from Isle of View, introducing Jenny Elf, and then in the Author’s Note introducing Jenny herself. I explained that she would be there, and that though she would understand what was said to her, she was paralyzed and would not be able to respond readily. I felt that with this caution, the folk at the convention would treat her well. I was not disappointed; they made her more than welcome.

Saturday was the big day. I had breakfast at 6:30 with Richard Pini, and we discussed the prospects for the graphic novel. It should be published in three parts, the first part preceding the text novel and the third part following it. We hope that this combination will introduce Xanth readers to Elfquest, and Elfquest readers to Xanth, and be a success. Wendy Pini will not be drawing it; she has other commitments. But they have a good artist in mind, and it should be an impressive volume, and a ground-breaking one: the first cross between these two fantasy realms, unified by Jenny Elf.

I met Toni-Kay, here at my behest, and her friend Barbara, from New Jersey. I have corresponded with Toni-Kay for years, and have several nice paintings of hers— duck, rabbit, horse, piliated woodpecker, alien creature—generally naturalistic, rounded and soft, like Toni-Kay herself. She credits me with turning her back into painting; she may be too generous, but certainly art is in her nature. I had commissioned a painting of cats from her, for me to give to Jenny, and prevailed on her to bring it herself. Because Jenny could not stay the night, the room was available for Toni-Kay and Barbara to use without charge, and Jenny’s family welcomed them. I understand they were most compatible—four Avon Ladies, they said—and perhaps that will be a lasting friendship. Things just seemed to come together in special ways for this occasion.

Jenny arrived at midmorning, and after she had gotten settled—travel is difficult for her, because she gets carsick in addition to her paralysis—I went in to meet her. I have no trouble facing audiences of any size, having long since abolished stage fright along with writer’s block, but I felt a bit of nervousness at that moment. I was finally going to meet Jenny! There she was in her wheelchair and her big spectacles, looking just like Jenny Elf only with rounded ears. She can move her limbs somewhat, but has real control only in her right hand, so she is able to finger-spell, slowly. She can turn her head and move her eyes, and will blink to say yes. She suffered multiple injuries and fractures in the accident, but apparently it is damage to the brain stem that is responsible for the paralysis. I think of it as being like a cable that has been mostly severed; only a few strands connect, and it is problematic whether others can be reconnected because the doctors don’t know what is supposed to go where, and might make things even worse if they messed in. She was twelve when it happened, and is now thirteen, becoming a young woman. She can move her jaw, but not enough to close her mouth completely. She can not speak, but can laugh. I sat before her, and took her hand, and tuned out the rest of the world. [What I said to her is a personal report, “Let Me Hold Your Hand,” personal and intense.]

On Saturday, NoRemember 11, 1989, I met Jenny in her hotel room at the Sci-Con 11 science fiction convention. She was in her wheelchair, wearing her big glasses (Mundane spectacles), unmoving, expressionless—or, as her family later described it, rapt. This is what I said to her, from memory—or perhaps what I meant to say, as I may have garbled words or sentences and gotten things out of order. I tuned out the others present; it was Jenny and me in the foreground, and the rest of the world in the background. There was an interruption at one point, and I lost my thread and skipped part of what is here. So this written version may be more complete and precisely worded, though the emphasis and feeling are muted here; the essence is the same.

***

Jenny, I have to do things my own way, and I don’t always go directly to the point. So bear with me while I say some things which may seem irrelevant; I will get to the subject in due course.

When I was in college I learned a folk song, “Come Let Me Hold Your Hand.” The refrain referred to Peel and John Crow, and at first I thought it was racist. But it isn’t; it is Jim Crow who is the symbol of racism in the south. As far as I know, these are real crows: Peel and John, who sit in the treetop and watch what’s going on below.

When I wrote the first Incarnations novel, On A Pale Horse, I incorporated a line from that song. It was in a scene with a woman who had just had her father die. She loved him and missed him, and all she could think of was this song. This happens to people suffering grief; they have to block out the big thing, and focus on some little thing that is not so closely connected. So she thought of the way he had held her hand, and that bit of the song kept going through her mind. “It’s a long time, girl, may never see you; come let me hold your hand.”

But when I got the galley proofs, I discovered that the song was missing. In fact the whole scene was missing. It turned out that the editor thought I was borrowing from a Beatles song, and was afraid of copyright infringement. Now that song wasn’t from the Beatles; it was before the Beatles existed. Their song is “I Wanna Hold Your Hand.” But the editor would not relent, and though I got the scene put back, I had to make up other words in lieu of the song that weren’t as good. I regret that, and I am getting more difficult about editorial interference in my novels.

When I got in touch with you, I remembered that song. Now I will sing it to you, as I said I would in my letter:

It’s a long time, girl, may never see you; come let me hold your hand.

It’s a long time, girl, may never see you; come let me hold your hand. [At this point I reached forward and took her right hand with my left hand; the remainder of the song and monologue was with our hands held.]

Peel and John Crow sit in the treetop; pick up the blossom; let me hold your hand, girl, let me hold your hand.

It’s a long time, girl, may never see you; come let me wheel and turn. [Repeat line, and refrain: Peel and John Crow.]

It’s a long time, girl, may never see you; we all shall wheel and turn.

[Repeat first verse. It’s not that I’m a great singer, but that this song now relates to my feeling for Jenny, and to the theme of this discussion.]

It’s been a long time, girl, since I met you, and longer since you met me, because you knew me through my novels, while I learned of you only when I received your mother’s first letter. Now we have met personally, for the first time.

It is said that a person who saves the life of another person is thereafter responsible for that other person. I didn’t understand that, at first; it seemed to me that it was the one who was saved who owed the debt. But as time passed I came to appreciate the meaning of it. A person who is dying will not have much concern with this world. Whether he goes to Heaven or to Hell or to nothingness, he is finished here. But if someone else interferes with his life—his death—and brings him back to this world, then he may not be ready for it. He may have had reason to leave this world, and be ill prepared to handle it. So the one who brings him back should at least see that the life he returns to is worthwhile, and that he can cope with it.

When I wrote to you while you were in the coma I wasn’t sure that my letter would bring you out of it, but I gave it the best try I could. Now it may be that you had decided to wake up on your own, the day my letter arrived. That you said to yourself “Well, I’ve had a good sleep, and it’s time to get up. Oh, there’s a letter from Piers Anthony? How nice. What’s for lunch?”

Was it that way? [Here was the first reaction from Jenny: a trace of a smile, and perhaps a slight squeeze of her hand. Humorous negation: it wasn’t that way.]

But maybe you were walking through the valley of the shadow of death, and you faced resolutely toward that other world. Until my hand caught your hand, and held you, and turned you back toward this world.

Now understand, I did not do this alone. When my hand caught yours, my other hand was holding your mother’s hand, and her other hand was holding your daddy’s hand, and there was a line of therapists and friends extending from our world toward you. [At this point I reached back and put my hand on the arm of the next closest person, Jenny’s father, illustrating the chain.] But they could not quite reach you, until I came and added one more link, and finally caught your hand.

So I do feel responsible. The chain needed every link, and I was the last link. I helped bring you back to this world. Then I thought about it, and wondered whether it was right to have done this. If I had brought you back only to a life of paralysis, to a life of no joy—then maybe I had done you no favor. Maybe I should have left well enough alone.

But it was too late. I could not undo what I had done, and I think I would not have changed it if I could have. So I had to justify it.

When I was your age, I was not happy. I had not suffered as you have, yet I reviewed my life, and realized that if I could have the choice of living it over exactly as it had been, or of never existing at all, I would choose not to exist. But that was early in my life. As I lived longer, my life improved, not steadily—it was two steps forward and one step backward—until today I have what is by any standard a very good life. If I had to live it all over now, I would do so.

I realized that I had to do what I could to make your life worth living, so that twenty years from now you can look back and say “Yes, yes, it was worth it, taken as a whole, the bad with the good, and I would do it again.” So I wrote to you, and encouraged you, and tried to help you in whatever way I could.

This convention is part of that. I think your salvation lies in art, in your drawing and painting. With the assistance of the computer you may be able to paint as well as you could with full use of your body. There are several good artists here, and they will talk to you. There are many other things to see here, and I think you will enjoy it.

And Richard Pini of Elfquest is here, and he has something for you. [Jenny broke into a great smile.] I will fetch him now.

Then I introduced Richard Pini, and got an immense smile from her. Richard gave her a color portrait of Jenny Elf, painted by Wendy Pini, looking just like Jenny but with pointed ears. He treated her like a little princess, and I could see how thrilled she was. Her two favorite realms are Xanth and Elfquest, and representatives of both were here to be with her. It was my hope that she could have a really good day, and it was coming true.

Then Jenny had to rest, and I went with Toni-Kay to look at the art exhibit. There were many beautiful and strange paintings, my favorite kind. After that I had to go autograph books at a Waldenbooks. They were supposed to have Sci-Con flyers there, but didn’t par for the course. They limited it to hardcovers, so it was not pressed; indeed it was quite slack in the middle of the two hours they had scheduled. But it evidently sold a number of Total Recalls, my version of the big Arnold Schwarzenegger movie for next year. I had not had a chance to eat lunch, but they dug up some chocolate doughnuts for me, and I munched on them while signing copies. One of the fans gave me a package of whole wheat crackers and smoked cheese. This business of eating: I am a creature of regular habits, but forget the notion of regular meals during such excursions. Why I don’t like to travel, # whatever.

Back at the hotel, I met Jenny in her convention dress: purple satin (I’m a dunce about such things, but that’s what it looked like to me) with matching high-heeled shoes: her first pair. She was like a doll. She had a corsage of artificial roses, and she gave me one. I wore it for the rest of the convention, and took it home: my memento of Jenny. Toni-Kay presented the painting she had brought: “Cats in the Window.” It showed a cluster of the softest, furriest cats sitting in a boarded cobwebbed window frame. Jenny collects cats; there are twelve at her home, because no stray can be allowed to go unrescued. By one of those supernatural coincidences, the wrapping paper Toni-Kay had chosen matched the shade of Jenny’s fancy dress.

Then Richard Pini and I took Jenny to the art exhibit, along with her parents and the therapists from the hospital and Toni-Kay and Barbara, so it was a party of nine or ten. Jenny indicated which paintings she liked, and Jenny’s mother entered bids for them. Jenny was really quite choosy; her mind is all there, and only the connections between it and her body are weak. Ron Lindahn gave her his personal tour of his art on display, which art was most impressive; he and his wife Val were the Art Guests of Honor for this convention. I have associated with him for two years, since meeting him at the World Fantasy Con in Nashville and making the compact to produce the Xanth Calendars. Kelly Freas, the dean of genre artists, came to say hello; Jenny met him at a convention years ago, as a child long before the accident, and he remembered her.

We emerged to the main hall, and the folk of the convention came to meet Jenny. She was the center of attention, surrounded by people, while Richard Pini and I stood back and watched, ignored. That was exactly the way we wanted it. It was Jenny’s hour. There was a small woman in an Elfquest costume, and three huge Klingons from Star Trek who kissed Jenny’s cheek and posed with her for photographs. Jenny has on occasion been treated by other children at the hospital as if she is retarded; she is not, and it was infuriating. She just can’t talk or move well. Here at the convention there was none of that; no one talked down to her. They even presented her with an award for best costume.

Finally she had to retire to her room, because she can’t remain sitting for long. She was very tired, but also very happy. She hoped to come out again after resting, but couldn’t make it. It was unfortunate that everything had to be jammed into a single day; originally she was to stay for the whole convention, so that her excursions could be properly spaced. But the convention folk had done everything I hoped for, and made it a phenomenal experience for her. Jenny was like Cinderella at the Ball, the center of attention for the occasion.

I signed autographs at 5 P.M. After forty-five minutes someone came up and reported “You’ll be glad to know that the end of the line is now in the building.” It’s a good thing we limited it to one title per person! Someone gave me some homemade chocolate chip cookies; I was amidst signing and didn’t catch the name, to my regret.

Then we saw Jenny off. They tucked her Xanth cushion behind her head—my wife made that for her, and she keeps it with her—, loaded her into her wheelchair, and the wheelchair into the van and she was gone. She was tired, and I understand was falling asleep already, and that was surely best. But for me, and I think for many others, it was like the lights going down; the main event was over. She had been queen for a day, but now it was done.

In the early evening Richard Pini and I met with Kirby McCauley, who represents both of us, to discuss details of the graphic adaptation of Isle of View. Normally an agent represents the writer against the publisher, but this is a special project I’m into for love rather than money; my only concern was that the contract be fair to all parties. I hope the adaptation is a wild success and sells millions of copies and makes everyone rich—but I’ll settle for Jenny Elf coming to life in pictures as Jenny’s fantasy self.

I went to the Green Room, reserved for guests (as opposed to fans), and inquired what leftovers there were, as I had not had time for supper, and lunch had been those doughnuts. They dug up tofu salad, bagels and hot chocolate, being most accommodating. In fact the convention proprietors were good throughout; I told them how much I appreciated the way they treated Jenny. They knew that I had attended only for Jenny; in fact the program book lists me as the guest of Jennifer Elf, and they donated the proceeds of their Sketch-A-Thon to the Ronald McDonald House in Jenny’s name. I think that came to something like $900. I don’t have much use for McDonald’s, but I certainly approve of their House, which serves the families of those in distress, as it did for Jenny’s family when the accident was new and it was uncertain whether Jenny would live, let alone recover.

There were other programs, such as the Costume Dance, but that started at 11 P.M., past my bedtime. I would have stayed up for it if I could have gone with Jenny. As it was, I read myself to sleep on Conan the Defiant by Steve Perry; it was one of several books he sent me, when we were setting up for a collaborative project which I then scuttled for reasons unrelated to his merit as a writer. (I turned out six novels—almost 700,000 words—in 1988, and it will be only four in 1989—but one is the 200,000-word historical Tatham Mound, perhaps the major novel of my career. My schedule for 1990 stands at five, and I was simply getting overextended.) They say that Robert Jordan is the best Conan writer, but I liked this Perry Conan better than the Jordan Conan I read. Which is not to disparage Jordan; I am highly impressed by his major fantasy.

Sunday morning I discovered what had been there all the time: a big basket of flowers and fruit sent by Jenny’s family. I am a professional writer, an experienced observer who notes the nuances as well as the larger picture in all things. So how come I can’t see what’s under my nose? Had my wife been with me, she would have noticed the basket as we entered the room. But she had to stay home to feed the horses, because both our daughters are now in college and can’t do it. This was the first time I had traveled alone since the 1966 Milford Conference. Why I don’t like to travel—oh, never mind.

So my meals thereafter consisted of wheat crackers, chocolate chip cookies, bananas, apples and grapes, all provided as gifts from those attending the convention. The pears, unfortunately, were like rocks, being unripe, and the apples were borderline; apparently the folk who provide these items are more interested in appearance than consumption. Thus the best intentions of those who pay for these things are diverted by those who assemble them. I did not dare touch the oranges; the acid sensitizes my teeth, so that I can’t even brush them without pain. But the rest helped, and I got through, despite getting sensitive on the left side. Well, a week or so would see that fade. Why I don’t like to—forget it.

Ron Lindahn showed me eight of the pictures for the 1991 Xanth Calendar, and they were phenomenal; the artists are outdoing themselves, and it should be an even better calendar than the 1990 edition. I suspect that the existing one is already just about the best calendar in the genre. (I know, I know; let’s just leave the critics out of this. They always have another opinion. I should mention, however, that there is also an Elfquest Wolfriders Calendar for 1990, and yes, Jenny has one of those too.) I am the sponsor of the Xanth Calendars; I pay for them, Ron Lindahn makes them up, and then we sell the package to the publisher for printing and distribution. That way there is no editorial interference, and we can do the best job for the calendar and the artists. Now if only we can get better distribution …

At 10 A.M. I joined Guest of Honor Todd Hamilton for autographing the Visual Guide to Xanth only. We were ready, the fans were ready—but it seemed that every copy of the book in eastern Virginia had sold out and neither stores nor distributor had any more. Now this might be taken as an indication of really hot selling—but the truth was unfortunately mundane. The publisher and distributor had simply not provided enough copies. There is nothing like a self-fulfilling prophecy: decide which books will not sell, and distribute few enough copies to guarantee it, never mind how many folk actually want to buy them. It is not the first time I have been rendered from a best-selling author to a low-selling author by the carelessness of others. I had not even received my author’s copies, though the book had been on sale for several weeks; Ricia Mainhardt had gotten some from the publisher, and she gave me one for myself and one I could take, suitably autographed, to Jenny. Thus it was that I discovered significant errors in the volume. Sigh. I had gone over the text, but hadn’t seen the late charts and illustrations. Most of the fans simply could not get copies, so the signing was a fair flop. This is unfortunately typical. When writers take over the world, things will be run better. Why I don’t like to travel to autograph: begin a list. At any rate, I took advantage of the slack to introduce Toni-Kay to Todd, who gave her advice on marketing her art and passed her on to Ron Lindahn, who gave her more that I hope will enable her to move forward in a career in art. In art, as in writing, there are folk who have talent but who aren’t into the swing of marketing; the right advice can make a significant difference. You need everything to make it: talent, persistence, good advice, luck and compromise.

At noon I went to the panel on Marketing Your Writing which I shared with my agent Kirby McCauley and Ricia Mainhardt, also an agent. My name was underlined, which meant I was the moderator. Ha! I grabbed the mike and started joking about agents. But I think we did manage to provide some solid comment and advice for hopeful writers, and I think it was a good panel.

As soon as it was over, we bugged out. I had a date with Jenny at the hospital. Her father drove me up there; it was about seventy-five miles through lovely autumn-turning forest. It was a nice place, in a parklike setting, with a number of separate buildings. Jenny’s ward was much like a nursery school, only with children of all ages. All of them are there for rehabilitation; their degree of incapacity differs. I suspect that two with the greatest body limitation and most alert minds are Jenny and her former roommate Kathy.

I asked whether Kathy could join us, and she came in her powered wheelchair, which she can control with her right hand on a button. Her range of motion seems almost as limited as Jenny’s, but she can control the wheelchair and also use her little computer to activate preprogrammed sentences. Her ailment has drawn her mouth up so that her upper teeth and gums show, and she is smaller than Jenny though about six years older. What she lacks in appearance she makes up in personality; she is a sweet girl. It is a fault of our species that we tend to judge by physical appearance rather than inner nature, and folk like Jenny and Kathy suffer unfairly. I had the impression that Kathy was thrilled to have been invited.

I showed Jenny the original drawing from Visual Guide to Xanth that Todd Hamilton gave her. I gave her the copy of the Visual Quide which Todd and I had autographed for her. Then I presented a little gift of my own: a “magic” quartz crystal, set with a small purple amethyst, on a silver chain. “You expected a red amethyst?” Jenny finger-spelled archly to her father. I put it on her, fumbling with the tiny catch. I gave another to Kathy, with a red garnet inset, surely surprising her. Then we went into Jenny’s room so I could read to them in private.

What I read was “Tappy,” a story I wrote twenty-six years ago and wasn’t able to sell. I regard it as the most sensitive one I have done. Two years ago I placed it as the first chapter of the ten-author Light Years novel, but when that project foundered I bought it back (actually I’m buying the entire project) and converted it to a collaboration with Philip Josée Farmer, in which we alternate chapters. Why go to all this trouble for a story? Well, it’s a special one, and who would pass up a chance to collaborate with Farmer, one of the remarkable authors of the genre?

So I read it to the two girls, and I believe they liked it. It is an adult story about Tappy, a thirteen-year-old mute girl who was maimed and blinded in the accident that killed her father, orphaning her as a child. The protagonist is a twenty-two-year-old hopeful artist hired to drive her to a clinic in another state. As he comes to know Tappy, his doubts about the nature of his job increase; he fears she is to be incarcerated in an institution so she won’t be an embarrassment to her guardians. He stops at a motel in the Green Mountains of Vermont, reads to her from The Little Prince, takes her hiking to a mountaintop that seems to fascinate her, and treats her like the human being she is. But he is too feeling; when he attempts to comfort her, he is swept by emotion and makes love to her. He is horrified, well understanding the law on statutory rape. But Tappy gains confidence as he loses it, and leads him up the mountain again at night. At dawn she draws him into a large rock which had been solid by day; it is a portal to elsewhere. Neither of them has reason to remain, in our world, and this is their escape. Phil Farmer, in the second chapter, describes the alien world they emerge in, with strange creatures and plants, and an enormous space ship. The novel is on its way.

I read this story because aspects of it are similar to Jenny’s situation: Jenny is thirteen, and severely hurt in an accident. Tappy is blind; Jenny is paralyzed. Both are mostly mute, but can hear and understand perfectly. The story’s protagonist is a hopeful artist; so is Jenny. Tappy faced the cruelty of indifference or censure by others, because of her condition; so does Jenny. It was a calculated risk, reading a story involving statutory rape to Jenny, but I felt that it is not appropriate to censor adult material that relates so nicely to her situation. The “safe” course would be to read Xanth, with its puns and simple elements, but how long can a person exist on only that level? “Tappy” relates to what is real, despite being the lead-in to what is fantastic. So I risked it, and hope that what I did was right.

Jenny said she liked the story, and I saw Kathy’s flash of pleasure when I described the phenomenal new world to which Tappy went. So perhaps the reading was a success. I have read to audiences of hundreds with less trepidation than this! I came to the convention to meet and talk to Jenny, and to read to her, and all the rest of the convention was less important to me than my interaction with Jenny. I never concealed this from the folk of the convention. Instead of being annoyed, they applauded my attitude.

Kathy touched a button on her computer, and it said “Please sign my point sheet.” They get points for good behavior and progress, and can use these points somewhat like money for privileges. It’s an incentive system that seems to work. The therapists have to sign the sheets, documenting the points earned in each session. What she wanted was an autograph, so I autographed the margin of her point sheet. Then of course Jenny wanted hers autographed too.

As I was leaving, Jenny spelled out something. Her father translated: I had called her Kathy instead of Jenny. Sigh; I do make such slips, and she had caught me.

On the drive back we saw a deer, a stag, standing by the side of the highway. He finally bounded back into the forest. Then we saw a cat who threatened to dash in front of the car, but finally got off the road. Jenny and her mother are vegetarians, as I am; nobody in her family runs over animals.

Back at the convention I talked with Jenny’s family, and we went to the late show: we had missed the Lindahns' slide show, but they were rerunning it for the convention personnel. I had not attended a single convention function other than those where I was onstage; I had been busy with autographings, Jenny, and meetings with professionals. Sometime I would like to go to a convention and see the sights and attend the programs, as ordinary fans do, but I fear that is not feasible. The slide show was of Ron and Val Lindahn’s paintings, with a musical background, and it was impressive and evocative. They are great artists and great people; I respected Richard Pini and Ron Lindahn before, but after seeing how they treated Jenny, I respect them more. I was also impressed with the convention itself, for similar reason; they all worked together to make this perhaps the greatest experience of Jenny’s life since the accident.

Ron Lindahn had me sign his autograph book, in which each person addresses the subject of the Meaning of Life. I pondered, and wrote: “Honor Compassion Realism” and signed it. Each of these words bespeaks volumes in my philosophy.

Monday morning I checked out, using my MasterCard for the first time; it actually worked! I had half expected it to malfunction, because that’s the nature of things when I try to handle them. I remember the one time I tried to make the ATM cash vending machine work; it kept giving me error messages, until my wife explained that it was registering cents instead of dollars, and it didn’t give out cents. Then why was it registering them? I was just supposed to know without being told that a machine that handled only dollars nevertheless registered numbers in cents. Evidently that makes sense (or cents) to the rest of the world. At any rate my bill was in order, except that they had charged me two dollars more for my restaurant breakfast than the bill had showed at the time. I had left a two-dollar tip on the table; maybe they added it to my bill. I don’t claim to comprehend the logic of the world. That two dollars for the tip was the only cash I spent on the trip, which perhaps suggests how I handle money.

Jenny’s father drove me to the airport, and this time it really was a ten-minute drive. Everything was going suspiciously well. Could my curse of traveling be giving out? After he left, they canceled my flight. Why I don’t like to travel—sigh. They don’t do that sort of thing when my wife is along, which is why I hate traveling alone even worse. I wound up on a plane bound north to Baltimore. I was just in time; I think I was the last person to board, and got the last seat available, and it took off right after. Jenny’s rose, pinned to my carried jacket, was taking a beating as I bundled in. I know it’s artificial; that still bothered me. It was as if Jenny herself was getting battered. I heard that three of us were being routed that way to Tampa. I heard the girl in the seat ahead of me mention Tampa, so I inquired whether she was one of the others. No; she turned out to be a stewardess. Ouch; I found such an innocent confusion acutely embarrassing. Then at Baltimore I inquired and found the gate for the plane to Tampa. They were in the throes of rerouting passengers for a canceled flight to Albany. USAir seemed to be canceling flights all over! I phoned Cam, and after several attempts with the newfangled computer-screened phone managed to get my collect call through to her. Phones don’t like me. I caught her about forty-five minutes before she was due to start out to meet the plane I wasn’t on. I don’t know how we would have connected otherwise. In short, this was normal traveling, for me. I’d rather stay home.

I read during the flights and delays, and managed to finish the Conan novel, and look at two fanzines I had been given along the way. One was The Knarley Knews, a small personal production, and the other was Anvil, its fiftieth issue, put out by Charlotte Proctor. That’s a solid production, but it runs the addresses of those who write it letters, so I won’t.

The new plane served a good meal for me. The flight started on time and arrived early. I had an aisle seat near the front; I got out fast and spied Cam studying the schedule to spot my plane, not realizing that it was already in. We hurried to the car and skimmed through the beginning of rush hour; that surely saved us a good chunk of time. That’s why I don’t check any baggage; not only would they lose it, because of my curse, I would suffer critical delay. As it was, we were an hour late feeding the horses; fortunately they were nice about it. Cam had during my absence put a new picture up in the family room, and set up and filled four new filing cabinets with my year’s correspondence. Twenty letters had piled up, and ten more came in the next day, and a dozen more the following day. It was evident that I would get little if any paying work done this week. Sigh; I was back in Mundania.

NoRemember 17, 1989

Dear Jenny,

Well, here I am safely back at home. Your folks probably told you how USAir canceled my plane flight after your daddy left me at the airport. That’s why I don’t like to travel. They wouldn’t do that to my wife, or to your folks, but there I was alone, so they did it. I had to go home by way of Baltimore: that is, I flew north, and then south. I was an hour late feeding the horses. Sigh. But I don’t need to go into all that here; I have written up a report on everything that I will send to my family at the end of the month. Yes, you get a copy. I just like to get things written down, before I forget the details. So if you want to know about the convention from my point of view, tell your daddy to read it to you. No, you don’t have to! I know you were there! Oh—that’s not it? I don’t know how to read your finger-signs. Do them again slowly. DOES IT INCLUDE—oh, yes, it includes what I said to you when we met. That’s a separate report, more private, titled “Let Me Hold Your Hand.” But why should you care about that? You already know what I said. Oh—you want to make sure I wrote it down right. It really doesn’t read as I said it; things that were important just look like dull words, and more time is taken on the trivia than on the essentials. But here’s a copy.

Yes, that’s what I meant: a copy. I printed one copy on the laser printer, and then took it down to the copy machine we bought yesterday. It’s a Mita DC 1205; I think the number means that it makes 12 copies a minute, or five seconds per copy. It does; I timed it. We realized that we have to do a lot of copying, and it’s a pain to go into town and feed money into the machine, so we shopped for a copier we could use at home, and this is it. It’s so simple to operate that even I feel at ease with it. So your Convention Report is a copy which looks just like the original. Sure, I could have run off more copies on the laser printer, but this is twice as fast, and anyway, I wanted to make sure it worked. The same day we got it, I received a letter from Philip José Farmer asking for a copy of his Chapter 2, which he no longer has; now I’ll be able to make it for him. That’s the second chapter of our collaborative novel; I read the first chapter to you and Kathy, remember? You don’t? When I visited you at the hospital, and accidentally called you Kathy—yes, that time. And you are never going to let me hear the end of it, are you! Farmer will now do the fourth chapter, because I’ve already done the third, and we’ll give it to my agent to sell to a publisher. My agent is Kirby McCauley, whom you also met; yes, I know you don’t remember, because it was only a few seconds, but he was there. So you see, you are involved, one way or another, in more than one of my projects. When we finish that novel I’ll send you a copy, so you can see how it turns out, if you’re interested.

Meanwhile, my nose is fauceting; another allergenic front came through, and antiallergy pills for me are like anti-motion-sickness pills for you: they make me sleepy without stopping the allergy. Sigh. Tomorrow McCauley and a man named Wil Nelson will be here, so I can see the five minute sample of the first Xanth video movie and decide whether it’s good enough to proceed with. No, that’s not the graphic version of Isle of View, silly; that’s what Richard Pini is doing. This is A Spell For Chameleon on video tape. If we do it. If things fall into place. And I’ll have a sore nose. This is what my life is like. Yes, I realize that it’s not your nose that’s sore! It’s still a nuisance and a pain.

Let’s see: you told me not to write two Xanth novels next year. Was that because you’re tired of Xanth? Oh—because you figured I’d be working too hard. Jenny, it’s not like that. I’m a workaholic; I’m always working. If I don’t do another Xanth novel, I’ll be working on something harder, like my novel about the sociopaths. You know, folk like the one who ran you down with his car. It would be more pleasant to be in Xanth. So I may do it, if the publisher really wants it.

Meanwhile, I have some accumulated clippings for you: comics and such. I’ll dump them in with the Convention Report. It’s not that I’m trying to get rid of you, Jenny, but my dripping nose is making my face hurt, and I just have to lie down somewhere and read something. Otherwise I have to wipe my nose constantly, or it will drip into the computer keyboard, and that’s really not best.

Have a good week, and let me know how you liked the convention. What do you mean, what convention? The one that came into existence just for you, Jenny, so you could be princess for a day.

NoRemember 24, 1989

Dear Jenny,

Harpy Thanksgiving! Yes, I know it’s over for you, but we’re in the throes of it here as I write this. No we didn’t eat any turkey! We didn’t eat any harpy either. We’re a family that serves the stuffing without the bird. My two daughters came home from their separate colleges, and we ordered new computers for each of them, and today the man brought them and set them up and the girls are figuring them out. You see, we wanted to get them, aligned with us, so they can do homework when they visit home, and so the computers have to be compatible. We got them nice printers, too: they are dot matrix with 24 pins (that’s good—ask your mother) that can print regular or script so well it doesn’t look like dots at all. Penny grumped because it wasn’t a laser printer. Sorry; I don’t trust something that expensive in a college situation. All we need is someone spilling iced tea into it. Meanwhile, Cheryl is using my stereo system to transcribe music from her CD disk to her cassette tape, because she has a tape player but no CD player. And I showed the girls how to set underlined words on the screen in blink. Now I’ve set my own “Bold” in highlighted blink mode. See? BOLD Well, I know my screen isn’t there; you can just imagine it. Innocent fun. Anyway, we’ve been busy; how has it been with you?

Your mother was asking for Kelly Freas' address, having thrown it away before. Okay, I’ll tell you, and you tell her. If she loses it again, tell her again.

Speaking of your mother: she was naughty. I gave your daddy a copy of Pornucopia, which is my Super Adult Conspiracy XXX-rated close-your-eyes-while-reading Not For Women And Children censored novel—and she read it! Naturally her brain now looks like rotten eggs on drugs. So if she visits you, and she seems to have swallowed all her teeth and suffered a foul-smelling jawbone infection, that’s why. What’s that? NO, YOU MAYN’T READ IT TOO!! Haven’t you been paying attention, girl? Stick to Xanth, where stuff like this is banned.

It was nice getting to see you and Kathy at the hospital. I understand you have a new roommate now, named—wait, that’s your name! You mean she’s Jenny too? How will you tell each other apart?

I forgot to give you the two magnolia seeds I brought along. I saved those from way back, when they kept getting crushed in the Post Orifice, so finally I had to bring them myself. That’s why I came, after all. I remembered them Monday morning, so I gave them to your daddy. You mean he forgot too? Well, demand them; he has them somewhere. If they sprout in his shirt pocket he’ll look like a walking magnolia tree.

Some tag-ends about that hospital visit: I thought of the quartz crystals I gave you and Kathy because they are in Tatham Mound. The Indians believed they had healing properties, and could be used to tell the future. So if you recover more of your powers, you’ll know why. I hope Kathy liked hers; she didn’t want to put it on, but maybe she was just too shy. I wonder if she really didn’t receive that letter I sent her over a month ago. I have it on the computer; I can send it again if I need to. And about that song I sang you: “The Eddystone Light”: it’s a funny song about the sea, and I thought it would make you laugh, but it didn’t. Sigh. These things don’t always work out. Actually it wasn’t easy to get much of a reaction from you on anything. I worried that you were falling asleep when I read “Tappy.” Kathy was awake, but you were getting uncomfortable. And I never got to meet that boy you mentioned—I can’t remember his name now, which is par for the course; I can’t remember any names without rehearsing them. Oh, well; the way we picture things is seldom the way they happen. It’s a nice hospital, and I’m glad to be able to picture you there.

Which means you’ll be moving soon, so my picture won’t count. This is in the nature of things.

Meanwhile we have progress on that project to make a video tape from the first Xanth novel. The man who is working on it came to visit me last week and showed us his five minute sample. It’s okay but not phenomenal; he said it costs $9000 a second to make such animations, and he doesn’t have that kind of money, so had to fill in with still pictures. Yes, nine thousand dollars a second! That’s more money than your mother makes, even when her teeth aren’t bothering her. But it seems like a good project, and we’ll probably go ahead with it.

Did you hear the news about Kimberly Mays? She’s the girl who turned out to have been baby-swapped in the hospital ten years ago. The Mays family got her, and the Twiggs family got the other girl, and only now have genetic tests confirmed it. So Kimberly was in effect adopted. No one knew, except whoever swapped the babies, way back when. Imagine what it would be like if you turned out to have been swapped: then someone else could be in the hospital and you could go home to strangers. I don’t know; that might not be that much fun. I understand Kimberly is upset about it. Strange things happen on occasion!

Well, Jenny, say hello to Jenny for me. I only have one enclosure for you this time: “Curtis.” Yes, you may show it to Jenny too. Have a harpy week!

NoRemember 30, 1989

Dear Jenny,

Friday is my Jenny-letter day, but I’m doing this on Thursday, because I’m wrapping up much of my correspondence for the month now and want to keep the first of next month free for paying work. If I can get in four more good days, I can finish Ore’s Opal except for the editing, and be just about on schedule for the next novel, Virtual Mode, which features the suicidal fourteen year old girl. What would happen to the world if you turned fourteen and I didn’t have that novel done, so I couldn’t read you a chapter from it? (Would you believe: I typed control-O instead of control U to underline Orc, and it jumped me to the top of the paragraph, inserted a ruler, and started typing there. Apparently control O followed by O does that; it’s part of the “O” roster of commands which Sprint has but doesn’t list; they are there to emulate one of the other stupid word processors that do things in peculiar ways. Remember what I told you about how computers are always out to get you? Believe it!) Mode should be published in 1991, and maybe catch your Last Days of Fourteen. See, there is order in the universe. You’ll like Colene; she’s not at all like Tappy, but she’s all girl. You might get the notion from all this that I like girls. Right; I’ve been tuned in to girls ever since my first surviving daughter was born, and maybe even a bit before then. A correspondent recently wrote me to tell me that she had just had a son (she appeared in Xanth as Emjay, who married the Ass who helped her compile the Lexicon of Xanth). I wrote back that she should keep trying, and maybe next time she’d have a daughter.

Meanwhile, what’s doing here? Well, on Tuesday we had our thickest fog yet. It made the morning forest quiet, a wonderland of only close things, no distant ones. It’s probably easiest to reach Xanth from here on such mornings, because the magic trails have proper concealment. I think it was such a morning that Jenny Elf crossed over into Xanth from the World of Two Moons, starting a complication that the Muses still haven’t quite resolved. Which reminds me: I tell them not to do it, but I have had experience with my fans, and they’ll do it anyway. They will write letters to you, sending them to me through the publisher. I’ll have to send them on to your mother, who will have to read them to you, and then you’ll have to answer them. So be prepared for your fan mail, Jenny, after Isle of View is published. Because I know you will intrigue the readers the way Ligeia did.

Which somehow has led to my next subject: much as I’d like to see you recover the full use of your body, and become a marathon gymnast, and live happily ever after, I have this nagging little suspicion that you will have to settle for something less. But I feel that the computer can bring you a great deal of joy, once you get around its out-to-get-you syndrome. All you need is a way to input it, and it doesn’t really matter whether you use a finger or your head or your big toe. (No joke; if you have good control over that toe, they can set you up with a toe button to operate it.) Then you can have sentences programmed, such as “Thank you for writing to me. I still can’t walk or type, but with the help of this computer I can answer you. I’m sorry to learn that you also got hit by a car. Doom to all careless drivers!” You can have a signature block made up, even. Your mother could program that sort of thing, I’m sure. Did I ever show you my Xanth stamp? No? Okay, here is one; don’t try to use it in Mundania, though.

So you see, much can be done with the computer, and not just sentences. You’ll have a ball with a drawing program. First get a good way to direct the machine—maybe a little “Thinking Cap” that is attuned to the small motions of your head—then enter the wonderful world of increasingly proficient control. It really is like a magic realm. I was dragged kicking and screaming into computers; I wouldn’t have changed over from pencil and manual typewriter if they hadn’t stopped making good manual typewriters. But once I really got into the computer it was wonderful, and I really wouldn’t trade it. Those little talk-box computers you and Kathy have are fine, but I’m thinking of the heavy stuff, that has the potential to tune you in to the larger world so well that others would not know your situation unless you told them.

Say, maybe we can make a Jenny stamp! Let’s try it:

Anyway, I now have a nice mental picture of you at the hospital, though I guess you won’t be there much longer. I also have one of you in your fancy go-to-the-ball gown, with your matching shoes. Actually, I thought your little bare feet were cute, too. I have your rose by my computer; I see it sitting there and I think of you, between paragraphs.

Meanwhile, back here, we had another visit by the cows. They were suddenly grazing right by our house: Elsie Bored, How Now Brown, Bossie, and one whose name I didn’t catch. We phoned the sheriff, and that afternoon he came and shooed them back onto his property and patched his fence. Air-boaters on the lake keep breaking it down, and then the cows get out. I guess those boaters don’t know whose fence they are so cavalierly violating. One of these days they may find out the hard way. Which reminds me: we have deer on our property, and there’s another deer who joins the sheriff’s horses, grazing in the field right in sight of passing hunters, leading a charmed life, because everyone knows whose horses they are and how he feels about his horses' friends. I wrote that into Firefly: a true story folk will think is fiction. But that deer hasn’t been seen for a couple of months. We hope some hunter didn’t—or some reckless driver. Maybe that deer got to know our deer, and is with them now. But we’re worried. Deer are so innocent, and hunters are such || CENSORED BY ADULT CONSPIRACY ||!

Which reminds me: I have played with the typestyle modes on this mono-mode system, and find there are seven ways to show print on the screen: plain, underlined, HIGHLIGHTED, Blink, invisible, blink/underlined and blink\HIGHLIGHTED. You can’t see several of those in the printed version, of course. But let’s try the invisible, and see whether it does or does not print: Invisible. On the screen that word does not show; if it doesn’t show when printed out, it’s truly invisible. Yes, it’s really there; I can see it when I go into Codes Mode: Invisible. Yes, I know, here I am wasting time instead of getting on with the letter. It’s my way. Meanwhile right now my wife Cam is wasting her time trying to make our DEC printer print from her IBM-clone computer; it’s supposed to be possible, but a new cable and several codes later it still won’t do it. We bought new computers for both our daughters, which are fine except that they insist on stopping after every page. We’ll get that ironed out in due course. Maybe you can find the setting on your computer that makes you invisible, Jenny.

A year and a half after we moved here, we still can’t open and close our front gate from the house. The radio signal can’t get through the jungle. This one is guaranteed for five miles, but we said “prove it” and they couldn’t. So now they are setting up a tall tower by the gate, which will transmit to our TV antenna, and it finally should work. The thing is, if I ever get famous and crowds of fans are trying to get in, I’ll want that gate closed—but we need to be able to buzz it open for deliveries and such.

And we received four boxes of fresh fruits from HOUSE OF ONYX. Sixty fruits in all. Brother! We have made it through the pears and are working on the apples. No, ONYX is a gem dealer, not a fruit dealer; it’s just their way of saying thanks for doing business with them. But four boxes?!

Do you keep up with Calvin and Hobbes? This past week has been fun. Calvin kept getting larger until he stepped right off the world and found a door deep in the universe, leading back to his room, Calvin has my kind of imagination.

You know, Jenny, when I was your age I used to imagine that maybe my life was all a bad dream, and I would wake and find myself back in England where I was happy. I suspect you have similar dreams. But my life has improved so much that now when I think of waking I fear it; my real life might be as an unsuccessful writer, and all my best-selling novels might have been a wish-fulfillment dream. So I’d rather stay with it. But if one day you disappear, I’ll know that you woke up and everything since the accident was your bad dream. Then you’ll read Isle of View, and wonder.

I’ll wait to print this out tomorrow, in case your mother has a last moment phone call saying “Don’t send it; Jenny just woke up!”