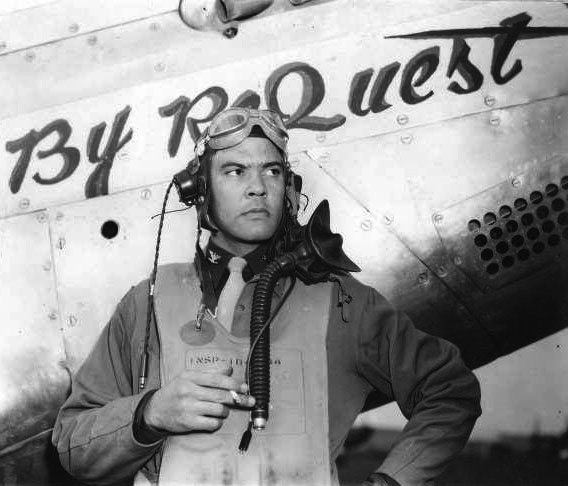

One of the few photos of Harry while deployed in Italy with the 332nd Fighter Group in 1945. Harry Stewart Jr.

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers; For he today that sheds his blood with me Shall be my brother.

—William Shakespeare, Henry V

Ramitelli had become the operational nerve center for the 332nd Fighter Group and its four fighter squadrons by July 1944. At that time, the 99th Fighter Squadron had already been in action for a little over a year; whereas the three other squadrons had experienced their baptism of fire in February 1944. Some members of the 99th reportedly bemoaned their squadron’s linkup with the relative greenhorns of the 332nd. And the reservations of the battle-hardened trailblazers were said to be reciprocated by some of the newcomers, who feared that the experienced pilots would crowd them out of plum assignments.

The 99th’s greater disappointment was that this consolidating of the all-black fighter squadrons into a single group precluded the once hoped-for synthesis with white outfits. As the Tuskegee Airmen’s initial in-theater combat squadron, the 99th had previously been attached to white fighter groups. From this perspective the consolidation was a setback. The fact that the 332nd Fighter Group had four squadrons, when a fighter group normally had three, showed the lengths to which the Army’s hierarchy would go to preserve the institution of segregation.

But the reservations in the fighter group about the conjoining of the new squadrons with the old soon faded. Starting in May 1944, the 332nd had been assigned to the Bari, Italy-based Fifteenth Air Force. In sync with the Eighth Air Force operating out of a multitude of bases in England, it pressed the bombing campaign to the enemy’s home territory.

The shift in focus from tactical missions, such as ground attack under Twelfth Air Force, to mainly strategic missions, such as long-range bomber escort under Fifteenth Air Force, meant a different kind of flying. The new missions would give the Tuskegee Airmen more of an opportunity to make a name for themselves. In July, the 332nd started flying missions with the P-51 Mustang, the most effective fighter that the group had yet operated.

Thankfully for Harry, the pilots of the 302nd Fighter Squadron who were already there took him under their wing. They mentored him as only grizzled combat flyers could, filling in the gaps in his stateside flight training, so that when his time came to face fighter pilots of the vaunted Luftwaffe in eyeball-to-eyeball encounters, he would be ready.

As things turned out, Harry’s affiliation with the 302nd was short-lived. On March 6, the squadron was inactivated to normalize the group’s structure so that it would have three squadrons like the other six fighter groups of Fifteenth Air Force. The 302nd’s personnel were disbursed among the 99th, 100th, and 301st Fighter Squadrons; Harry ended up in the 301st, where the mentoring continued.

During a panel discussion in 2012, when he was asked who his heroes were, Harry turned to the other Tuskegee Airmen on the panel who were a few years his senior and, with a knightly motion of his arm in the direction of those seated around him, said in his quiet voice, “These gentlemen up here with me now. They were there for me; they are my heroes.”

Harry’s first day at the base was less than auspicious. He remembers that “it was raining and cold . . . not a good first impression at all.” In the late-night darkness, he and his fellow replacement pilots were issued tent poles, canvas, cots, and so forth, and then told to set it all up on a designated spot. “It was about dawn before we had everything ready and finally laid down for some sleep.”

One of the few photos of Harry while deployed in Italy with the 332nd Fighter Group in 1945. Harry Stewart Jr.

When Harry walked the flight line, he noticed that all the Mustangs on the field had their tail sections and spinners painted a solid red. The markings had been adopted when the 332nd was transferred to Fifteenth Air Force. At that time, the Fifteenth Air Force commander, Major General Nathan B. Twining, ordered the group to adopt the solid red scheme as its identifying mark.

Decorating combat aircraft in assigned colors was in keeping with Army Air Forces protocol, whereby a group’s aircraft were made easily identifiable. Just by looking at the nose or tail markings, pilots could tell which group was in the air flying alongside them. Because the 332nd’s markings were not striped or checkerboard, and because they were a bright color, they were generally regarded as the most distinctive among fighter groups within Fifteenth Air Force. Not surprisingly, the group’s flyers became known as the Red Tails.

Color coding didn’t end there. Each squadron had its own identifying color. The 99th’s was blue, the 100th’s black, the 301st’s white, and the 302nd’s yellow. The squadron color was applied to the rudder and elevator trim tabs—the point being not merely quick recognition in flight but esprit de corps among the squadron’s pilots.

As part of Fifteenth Air Force, the 332nd soon established a reputation for success in protecting bombers on escort missions. Colonel Davis would write, “We took deep pride in our mission performance. Our pilots had become experts in bomber escort, and they knew it.”

He was especially happy with the compliments from bomber crews that came by teletype or telephone. “They appreciated our practice of sticking with them through the roughest spots. . . .” When the 332nd was increasingly solicited for escort by the bomber crews, Colonel Davis famously changed his fighter’s nose art. Painted across the nose were the words: “By Request.”

Despite January’s wintry weather and the muddy conditions around the runway built of pierced steel planking, Harry was excited to be a part of a winning organization. The morning after his arrival, he and the other new replacement pilots were shown their airplanes and introduced to their crew chiefs. Harry wasn’t sure how to start the conversation with his crew chief, Sergeant James Shipley.

Harry explained, “I didn’t want to ask ‘Is this my aircraft?’ because he might retort with ‘No, this is my aircraft!’ ” That first tentative interaction led to a lifelong friendship. Both men have continued to stay in touch, talking by phone every once in a while.

“The safety and preparation of the plane was entirely in the hands of Jim,” Harry was quoted as saying in Jim Shipley’s biography, by Jeremy Paul Amick. Keeping the fighter airworthy was a team effort, with Jim as the point man empowered to declare the airplane ready for flight or in need of grounding. Harry knew that his success—and his survival—in the air would depend upon Jim’s talents and work on the ground. “It was,” Harry says, “definitely a pilot–crew chief relationship.”

One day when Harry was not on the mission roster, he strolled down to where his aircraft was parked and found Jim performing heavy maintenance on the engine. It was freezing, but Jim wasn’t able to wear gloves because the task required the kind of meticulous tactility that was possible only with bare fingers. Jim compensated for the cold by blowing on his hands, trying as best he could to keep them warm. Observing such dedication reinforced Harry’s feeling that he had a great crew chief.

The bond between the two only grew over the next several months. In his biography, Jim is quoted as saying that Harry was such a zealous strafing pilot that on a couple of occasions the plane returned to base with “a bunch of gravel” in the coolant air intake, the conspicuous scoop on the Mustang’s belly. Jim would humorously scold Harry not to fly so low.

The day Harry met Jim, he was handed an instruction manual on his P-51 Mustang. Reading the manual and asking questions would be Harry’s only preparation for transitioning to the unfamiliar fighter. Before he was given the green light, Captain Dudley Watson, the 302nd’s operations officer, insisted he had to pass a “blindfold check” in which he was required to identify cockpit levers, switches, dials, etc. by touch only.

On January 20, Harry flew a Mustang for the first time, though not his own. Harry’s regular plane was a hand-me-down P-51C with the words “Miss Jackson III” emblazoned on its nose, because it had been the fighter of Melvin “Red” Jackson, the former commander of the 302nd. But if the pilot’s primary aircraft, the one tended to by his crew chief, wasn’t ready, another would be substituted. Before the end of the month, Harry made six orientation flights of from one to two hours each in all three Mustang models, the P-51B, the C, and the D.

Harry was pleased with his new fighter. It was smooth-handling and responsive to control inputs. In February, he started to fly escort missions, and because of their extended duration—in some cases, as long as six hours—he rapidly amassed flight time (more than seventy-five hours in that month alone) and became increasingly comfortable in the cockpit of the Mustang.

The Mustang was born out of Britain’s need for more first-rate fighters in a hurry when the resources of the Royal Air Force were stretched dangerously thin in defense of the empire in 1940. A British delegation came to America on a buying spree and in May of that year ordered a new fighter from North American Aviation that, on paper, promised to outperform what could be bought off the shelf. It was a leap of faith for the Brits; some might even say it was an act of impetuosity, since the contracted company had never built a fighter.

North American Aviation’s senior operating executives, James H. “Dutch” Kindelberger and John Leland “Lee” Atwood, had a strong personal interest in the project but turned to chief engineer Raymond H. Rice for engineering oversight and to inhouse design impresario Edgar Schmued for leadership of the design team. In a poetic irony, Schmued had been born in Germany and immigrated to America only ten years earlier. His central role in crafting the fighter that would contribute so much to the defeat of the Third Reich spoke volumes about the disparities in culture between the warring countries and the inherent advantages of America versus the Axis powers.

Despite serious racial and ethnic biases embedded in American society, the diversity of the U.S. population was represented in the war effort, with members of each group contributing their zeal and expertise. Hitler’s exclusionary model, in contrast, extirpated many of the Fatherland’s most capable citizens. The cause of freedom, though promoted unevenly by the U.S. at the time, was a rousing and unifying force even for shunned or ostracized communities. It was eminently fitting that the Tuskegee Airmen were among the pilots who flew Edgar Schmued’s extraordinary fighter to victory.

When Fifteenth Air Force’s white bomber units began calling on the 332nd Fighter Group for bomber escort, Benjamin O. Davis Jr. changed the nose art on his fighter to “By Request.” Air Force Historical Research Agency

A mostly self-taught aeronautical engineer, Schmued had been fascinated by airplanes for almost all of his thirty-nine years. As Ray Wagner describes in his biography of Schmued, the journey from Germany to the U.S. with a detour in Brazil was not easy, but the up-and-coming designer’s passion for aviation sustained him. After a career spent perfecting transports and trainers, the fighter assignment was nothing short of a dream job.

In fact, in the years leading up to this moment, Schmued had conceived of key fighter subassemblies in his spare time. Now he had his chance to pull his existing concepts together with state-of-the-art technologies in a clean-sheet configuration to maximize speed, maneuverability, lethality, and ease of construction. Fortunately, there was a wealth of talent within the company from which he could draw.

Among his team’s major innovations was the cultivation of a laminar-flow airfoil based on research conducted by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the government agency that eventually morphed into NASA. The wing shape, as viewed in cross-section, has a symmetrical top and bottom with the thickest point much farther aft than in a conventional airfoil. With this atypical configuration, boundary-layer air sticks to the wing for a comparatively longer time, resulting in lower drag and thus greater endurance and higher speeds.

Schmued’s team also adopted an interesting feature employed in a competitor’s design. The failed Curtiss XP-46 had a radiator scoop located in the lower aft fuselage, enabling the smoothing out of the fighter’s forward section. At North American Aviation the concept was refined with the water-cooling radiator, oil cooler, and aftercooler squeezed into the scoop. As the air passed through, it became heated and was then exhausted out a narrowed duct, actually producing thrust to partially offset the scoop’s unavoidable drag. This phenomenon, known as the Meredith effect, was named after the British engineer whose experiments in the mid-1930s discovered the secret for drag mitigation.

The Mustang’s design gave the pilot as many advantages as engineering considerations would permit. The main landing gear legs, for example, were set substantially outboard under the wings, giving the inwardly-folding gear an impressive spread of almost twelve feet when extended. This wide stance dramatically improved handling at takeoff and landing, in comparison to many earlier fighters with closely-coupled main landing gear.

One of the things Schmued insisted on was clean lines throughout the airframe. He told a colleague, “I want smooth surfaces.” So it was no coincidence that the Mustang had compound curves and flush skin joints.

The British had been promised a flying prototype in 120 days. Schmued set a more ambitious working group aim of 100 days. After laboring nonstop and generating an amazing 41,880 engineering man-hours and 2,800 drawings, the first completed airframe was rolled out between the internal and external deadlines.

But the Allison engine was not ready. The engine builder’s executives had not believed that the prime contractor could possibly develop an airframe from scratch in such short order. A rush was made to get the engine, and the first flight occurred on October 26, 1940. By the following August, Mustangs were being shipped to the Royal Air Force.

As anticipated, the new fighter was faster, with double the range of the latest Spitfire model in use by the British. But the Mustang’s climb rate and high-altitude performance left something to be desired. The answer to transforming the aircraft from a middling fighter to a superb fighter was blending its streamlined airframe with the incomparable Rolls-Royce Merlin engine.

The non-supercharged Allison was replaced by the 12-cylinder liquid-cooled Merlin 61, and the rest is history. Updates and modifications ensued, and the Mustang grew into a legend, widely regarded as the best all-around propeller-driven fighter of World War II. Its combination of an aesthetic profile with a superlative combat record has made it the epitome of warplanes.

The P-51B and P-51C were substantively identical, the only real difference being their construction sites. The former was built in Inglewood, California, and the latter in Dallas, Texas. The ultimate wartime model was the P-51D, which incorporated improvements that added to combat efficacy. These included a Plexiglas bubble canopy to enable 360-degree visibility; six wing-mounted .50-caliber machine guns compared to the prior models’ four machine guns; a dorsal fin faring to enhance stability; and the 1,400-horsepower Merlin V-1650-3 or -7.

The aircraft arrived none too soon as a long-range escort fighter. By early 1944, the fighters could be equipped with two externally mounted and detachable fuel tanks—75-gallon drop tanks and later, two 108-gallon drop tanks—that extended their range, so that heavy bombers could be protected on the longest missions.

Colonel Davis often led his pilots on the escort missions, which he preceded with memorable briefings in which he was always fully in charge; no whispering on the side. His stare was magnetic. You dared not look away.

Those who were there, sitting at close quarters in the briefing hut, say more than seven decades later that their leader stood with his trademark erectness, glaring at the flying officers assembled before him. And everybody could count on him coming out with his trademark stentorian exhortation, which the fighter group’s pilots knew they had to uphold at all costs. “Gentlemen,” he would exclaim with a messianic fervor, “stay with the bombers!”

Colonel Davis held his men to an unwaveringly high standard. It was as though he willed his fighter group to success in the long-range heavy bomber escort missions. His forceful personality had an almost hypnotic power that contributed incalculably to the remarkable record of minimal losses from enemy interceptors on the 179 such missions flown by the Red Tails.

Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Jr., commander of the 332nd Fighter Group, in the top row on the left, with crew chiefs of the 301st Fighter Squadron in front of a red-tailed P-51D at Ramitelli, early 1945. The colonel’s facial expression says it all—victory is the only option! Note the pierced steel planking used to facilitate flight operations. U.S. Air Force via Harry Stewart Jr.

When a maximum effort was called for on a big bomber mission, the 332nd’s four squadrons would each put up sixteen fighters and two spares, for a total of seventy-two Mustangs. Because Ramitelli had only one runway, the aircraft of two squadrons took off in one direction while the aircraft of the other two squadrons took off in the opposite direction. So much for aligning your plane with the wind!

The mass takeoffs were an amazing feat of both organizational coordination and pilot skill. Harry admitted years later that the first time he participated in one of these extravaganzas, he didn’t have a clue what was going on. He just followed the plane ahead of him.

A green flare was fired and the first plane started to roll down the runway. In what Harry calls “an intricate ballet,” the fighters that followed into the sky would form up on the leader, who would be maneuvering in gently ascending circles. Once everybody was airborne and gathering in the beginnings of squadron formations, the leader turned to a heading calculated to intercept the bombers on their way to the designated target.

The missions regularly involved hundreds of heavy bombers, the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and the Consolidated B-24 Liberators, each carrying a crew of ten, with strategic targets preselected in cities with war-related industries. The aircraft were layered in massive formations that stretched for miles from front to end, the likes of which were never to be seen again. Condensation trails would sometimes flow from the exhaust of the Mustangs, on the climb to cover them.

Harry’s squadron would stream the white lines in a magnificently symmetrical latticework that crossed with the trails of the other escort squadrons to form a colossal if temporary reticulation, an ostentatious show of men occupying different sections of the sky but united in a common purpose. Climbing higher than the bombers, typically at altitudes between twenty and thirty thousand feet, the escort squadrons were stacked one thousand feet above each other, starting at one thousand feet on top of the bombers. The escort squadrons flew an “S”-shaped pattern so as not to outrun the slower heavies underneath. Each of the four-engine bombers emitted an equal number of contrails, adding to the effect of a giant filigree superimposed against an endless blue slate.

The white plumes, splayed across cerulean skies for as far as the eye could see, evinced America’s unprecedented mobilization as well as the fantastic discipline, skill, and courage of the flight crews. From his aerie, riding shotgun well above the flying armadas of bombers, Harry was stirred by the sheer magnitude of the assemblage, especially on missions where he, as a junior member of his squadron, flew as Tail End Charlie. Harry, his eyes beaming, recollects that these spellbinding formations were “a sight to behold!”

The first sign that these missions were not a game but deadly serious came when flak began to punctuate the sky. Black puffs of smoke with flashes of red in the center appeared everywhere. When the bursts were close, you felt your P-51 shudder.

Worse, some of the bombers cruising below, caught in the field of fire, could be seen falling out of formation and sinking awkwardly earthward like toys made of papier-mâché. These mighty ships—metal molded into aerodynamic shapes and filled with fuel, bombs, and young men—were transformed in an instant into clunky deadweights whose fate belonged to gravity. The antiaircraft artillery shells came in salvos, seeming to damage bombers at random, as if a blindfolded contestant at a county fair were shooting rapid-fire at a row of rubber ducks and intermittently scoring hits.

Strapped tightly in his seat, encased under his Plexiglas canopy, and breathing heavily into his oxygen mask, Harry was overcome with a sense of helplessness as the scene played out. At escort altitude he felt closer to God, closed his eyes, and prayed for the poor souls peculiarly suspended in the sky below after having taken hits. Perhaps the flight crews could regain control and dead-stick their crippled planes to a pasture—or maybe the men aboard the tumbling giants could jump and they’d get lucky, floating down on their billowed parachutes into the welcoming arms of partisans in the Resistance.

Harry never really knew the fate of the bombers that were hit going in; though it seemed to last a lifetime, the drama passed quickly, and the mission always pressed on. Coming out of the target area, the escort fighters did everything they could to help their big friends in trouble. Colonel Davis prided himself on always ordering a couple fighters in the group’s formation to latch onto straggling bombers, affording them protection when they were most vulnerable to interceptors as they limped back in the direction of their home bases.

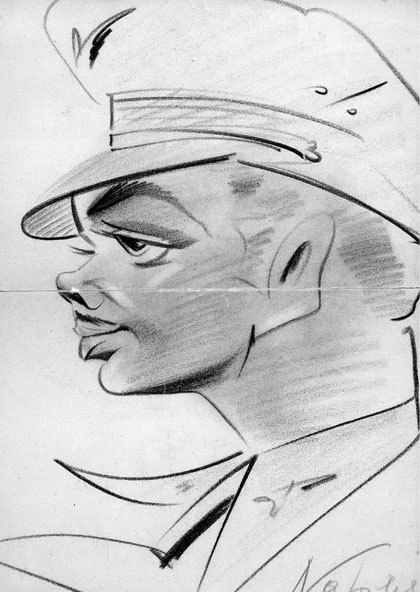

In February and most of March 1945, Harry flew combat missions—primarily long-range bomber escorts lasting up to six hours each—virtually every other day. In late March, he was sent to the 332nd’s rest camp near Naples, where he commissioned a street artist to create this caricature portrait of himself. Harry Stewart Jr.

Arguably, the 332nd’s most famous mission occurred on March 24, 1945. The group put up fifty-nine Mustangs to escort the 5th Bombardment Wing’s B-17s all the way to Berlin to hit the Daimler-Benz tank assembly plant. At sixteen hundred miles round-trip, it would be the longest mission flown by Fifteenth Air Force.

Harry was not on the mission because he had flown missions an average of every other day since being checked out in the P-51. He was at the 332nd’s rest camp near Naples, where a local artist was drawing his caricature portrait. Meanwhile, back at Ramitelli, his airplane had been borrowed for the mission by his squadron commander, Captain Armour G. McDaniel. As things unfolded, Colonel Davis had to drop out due to excessive engine vibration in his Mustang, and Captain McDaniel assumed the lead in Miss Jackson III.

The American bomber and fighter formations ran smack-dab against the Luftwaffe’s revolutionary jet fighter, the Messerschmitt Me 262. Dogfights broke out, and the Tuskegee Airmen shot down three of them. But the German jets inflicted their share of damage, too. According to one account, an Me 262 blew off the wing of Harry’s plane, causing Captain McDaniel to bail out. He survived and spent the remainder of the war as a prisoner at Stalag Luft VIIA.

When the group lost its frontline leaders, Colonel Davis replaced them quickly to avoid any lapse in the chain of command. Captain Walter M. “Mo” Downs was tapped to fill the vacancy left by McDaniel. A man of few words, Downs projected an aura of determination and was universally respected by the men of the 301st.

Upon Harry’s return to Ramitelli from the rest camp, he was informed of what had happened and was sent to Foggia to pick up a brand-new P-51D, the most advanced version of the Mustang. The shiny fighter had only five hours on the engine. It was so pretty and clean, Harry thought it would be a shame to fly it in combat—though he knew his fantasy was unrealistic.

When Harry’s crew chief Jim Shipley asked what artwork he wanted on the nose of his new Mustang, Harry had his answer at the ready. He was without a steady girlfriend at the time, so he chose the title of his favorite song, “Little Coquette,” a lively and popular ditty played by such notable bands as Duke Ellington’s and Guy Lombardo’s. It was that simple: the young pilot would plunge into his next round of escort missions in a dangerous machine decorated with the gaudy name of a big band tune.