Chapter Eleven

THE BEST OF THE BEST

Success is to be measured not so much by the position one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has overcome.

—Booker T. Washington

On June 19, 1948, the Soviet Union began to shut down road, rail, and canal access to West Berlin in what would develop into a full-fledged blockade later in the month. By cutting off the sectors of the city controlled by the Western powers, the Soviets were hoping to starve those sectors into submission and force the Allies out. West Berlin’s supplies of food and coal were estimated to be enough to last only thirty-six and forty-five days, respectively.

This was the first major crisis of the Cold War. Military action to address the provocation was ruled out as impractical. The United States, Britain, and France did not want to risk sparking another world war. At the same time, maintaining the Allied occupation was seen as essential to preserving the prestige of America and its partners.

So the Western powers agreed to resupply their sectors of the city through an enormous airlift. Because of West Berlin’s time-critical needs, resources were mobilized quickly. The resupply flights began four days before the end of June. The frequency of flights was eventually ramped up to an incredible rate of one every thirty seconds, with a total of eight thousand tons of supplies delivered daily.

The Berlin Airlift, referred to as the Air Bridge by West Berliners, ran well into 1949. It ended up shattering Soviet designs on the whole of the German city. But it demonstrated the need to be ready should the rivalry between superpowers turn hot.

The U.S. Air Force took the Soviet threat seriously. With the airlift in full swing, the hard-charging, cigar-chomping Curtis LeMay took over as the head of Strategic Air Command. He immediately went about revitalizing the service’s intercontinental bomber force to be prepared to devastate the nation’s nemesis with a massive nuclear strike. War planners knew that nuclear war would be catastrophic for both sides—an understanding that would later be formalized as “mutually assured destruction,” or MAD, the guiding principle behind a strategy of deterrence.

If rational minds prevailed, any war between the superpowers would be conventional—requiring highly skilled airmen capable of reliably shooting down enemy aircraft and putting conventional bombs on a wide range of ground targets. The Air Force was taking steps to prepare for this kind of a confrontation. Harry and fellow Lockbourne pilots would play a key role.

A first post–World War II, Air Force–wide fighter gunnery meet was scheduled at Las Vegas Air Force Base (later renamed Nellis Air Force Base) from May 2 through May 12, 1949. As the official program of events stated, “Lessons learned in tactical weapons competition will pay huge dividends for all of us should the need arise to engage another aggressor. We must develop these skills to survive in modern combat.”

Air Force leaders recognized that it is not uncommon for fighting skills to atrophy between wars. The answer to the problem would be to test and improve those skills. Indeed, the program of events pointed to “a return to basics” as the most important aspect of the competition and the way “to achieve professional excellence.”

With this first in a planned series of annual competitions, the Air Force was determined to up the game of every tactical fighter unit. The gunnery meet’s participants would return to their home stations and “transmit to the rest of the tactical air forces” the “improved techniques and tactics.”

The 1949 gunnery contests on the desert ranges sixty miles northwest of Las Vegas, in the area known as Frenchman Flat, validated the need for such exercises and proved to be a solid foundation for future competitions. Virtually all tactical fighter groups based in the continental United States were represented at the maiden event by their best pilots and maintenance crews. The meet was divided into two broad classes: jets and conventional (propeller-driven) aircraft. The contestants would be graded and ranked in five categories: dive-bombing, skip bombing, rocketry, panel gunnery, and aerial gunnery at both twelve and twenty thousand feet.

Selection was highly competitive. Colonel Davis decided to choose the team members that would represent the 332nd based on scores achieved at the last gunnery training mission, which had occurred at the auxiliary fields of Eglin Air Force Base in Florida’s panhandle during the preceding three weeks. For the pilots of the 332nd, scoring in these training missions was taken very seriously; they knew the results would be scrutinized by their superiors, including Davis himself.

Harry well remembers arguments breaking out among his squadron mates in the aftermath of a day’s gunnery practice over whose bullets had pierced a towed target sleeve. The tips of the .50-caliber bullets were dyed different colors to identify which pilot had hit the target, but sometimes the dye colors were not easily distinguishable—leading to the disputed interpretations.

A review of the rankings from the Eglin maneuvers showed that the three highest-scoring pilots were Captain Alva N. Temple of the 301st Fighter Squadron, who would serve as team leader due to his superior rank; First Lieutenant James H. Harvey III of the 99th Fighter Squadron; and First Lieutenant Harry T. Stewart Jr. of the 100th Fighter Squadron (having earlier been transferred from the 301st Fighter Squadron). The next in line, First Lieutenant Halbert L. Alexander of the 99th, was selected as an alternate. By a happy coincidence, all three of the 332nd’s squadrons would be represented on the team.

But the team’s enthusiasm about the upcoming meet was tempered by the fact that the U.S. armed forces had yet to implement President Truman’s forward-leaning desegregation order of the year before. The meet was to be another case—indeed, the last time—when a contingent of Tuskegee Airmen would fly in a large exercise with mostly white pilots, but still under the old modality of segregation. Harry would call it “the Last Hurrah.”

Just before the team departed Lockbourne for the Nevada air base, Davis gathered the four pilots who would be representing their fighter group at the gunnery meet. In a rare flash of humor, the steely commander sardonically stated, “I just want to say if you don’t win, don’t come back.” After the nervous laughter died down, he added on a more serious note, “Gentlemen, you know we are all behind you, wishing you all the best.”

With that energizing sendoff, the team’s three primary pilots and one alternate climbed into their late-model Thunderbolts for the trip west. Reminiscing, Harry describes the experience as an adventure—not just the gunnery meet itself, but concomitant events, including the cross-country traverse to the competition’s venue.

The outbound route included refueling stops at air bases in Oklahoma and New Mexico. The trip’s final leg was a straight shot from Albuquerque to Las Vegas. The four fighters flew in loose echelon formation across a mostly brilliant blue sky, as the scarred landscape of the high desert passed below.

Harry marveled at the sight of nature’s scraggy carpet, interrupted by ridged peaks, the variations in elevation distinguishable by the tincture of the terrain, the highest blanketed in snow. Along the course line, the San Mateo Range burst above the surface in ginger and russet, a sign that the Continental Divide lay ahead. Later the Painted Desert, with its oatmeal complexion bordered by caramel-glazed plateaus, came into view.

Near the destination, a rise in the surface was noticeable to the northwest. Off the flight’s starboard wings stood a mottled piece of ancient geological artifice with a peak topping out at over nine thousand feet. From a distance it was a mass of auburn accented by cinnamon-tinged ridges. The Kaibab Plateau was a defining feature, a checkpoint, on the tawny desert floor. The chart folded on Harry’s lap showed the Grand Canyon wrapped around the mighty plateau’s southern edge and extending westward in a squiggly serpentine form.

As Harry and his fellow pilots closed in on the landmark, mischievous thoughts quickly germinated; the daredevil in the team leader took over. Alva Temple angled straight for the mile-deep chasm and his teammates stayed with him, faithful to the bond between element lead and wingman. In twin two-ship tactical formations abreast of each other they held steady for the top of the canyon.

The pilots powered up their big-barreled ships to run like speedsters parallel to the rough-textured edge of the natural wonder. Man, machine, and nature blended together unrehearsed. The roar of the engines reverberated across the crusty landscape while the cascading rapids of the Colorado River continued to etch their ragged imprint into the canyon’s steep sidewalls below.

The sensation of the storied canyon surging underneath was as high a rush as pilots can get in peacetime flying. To one side Harry saw tourists lined up at eye level behind overlook railings. They were waving to him and the other pilots in a surreal blur as they blew past at breakneck speed.

Describing his feelings about the unique flyby, Harry said, “It was a sight that will never return.” For him the only flights comparable were his escort missions in the war, when cobalt skies were blazoned with countless strands of white contrails emanating from the prodigious heavy bomber formations.

This stunt en route to the gunnery meet contravened regulations. In fact, it was an offense punishable by grounding or possibly even court-martial. But the team members’ delicate admixture of self-confidence and audacity was typical of the fighter pilot milieu. The flat-hatting, hotdogging—whatever you call it—was arguably, up to a point, an expression of the attitude that naturally animated those flyers who aimed to prove themselves the best shooters in the whole Air Force. Tuskegee group commander Benjamin Davis was a stiff disciplinarian, but he knew the qualities required of fighter pilots and left them enough latitude so as not to squelch the aggressor impulse in the best of them. He chose his team well.

This first postwar service–wide fighter competition, known as the Continental Air Gunnery Meet, pitted the best pilots and crews of twelve fighter groups from across the continent against each other. The meet subsequently evolved into two much-ballyhooed biennial events known as the Gunsmoke air-to-ground competition at the same sprawling base in Nevada and the William Tell air-to-air competition at Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida. Gunsmoke was discontinued after the 1995 competition, but it resumed at Nellis in 2018. As an outgrowth of Gunsmoke, a biennial competition expressly for A-10 Warthog close air support aircraft known as Hawgsmoke started at a training range in Alpena, Michigan, in 2000.

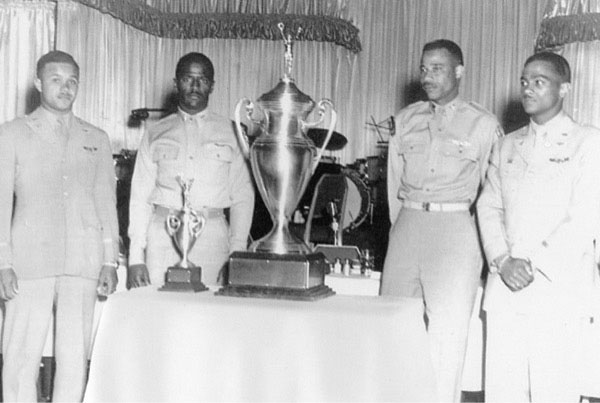

The 332nd Fighter Group’s team on the flight line at Las Vegas Air Force Base (later Nellis Air Force Base) for the first postwar Air Force–wide gunnery meet, May 1949. Segregation was still in effect. Team members, from left to right: Captain Alva N. Temple, Harry, First Lieutenant James H. Harvey III, and the alternate First Lieutenant Halbert L. Alexander. U.S. Air Force via Harry Stewart Jr.

Because of Las Vegas’s proximity to the open desert, the locale was ideal not only for gunnery competition but also gunnery instruction. The dry climate, superb visibility, and vast stretches of barren land spreading out from the city’s northern edge made air combat training activities common there in the years to come. These included the Vietnam-inspired Red Flag exercises to hone flight crews’ skills through intense air-to-air maneuvering and ground attack simulations. The Navy’s well-known Top Gun program at the Miramar Naval Air Station in southern California had started as a reaction to poor kill-loss ratios early in the Vietnam War, and it was eventually relocated to northern Nevada where it was combined with strike and sensor training to prepare carrier air wings for operational deployments.

Nellis became the headquarters of the Air Force Fighter Weapons School and the home of the Thunderbirds air demonstration squadron. Indeed, the base became known as the “Home of the Fighter Pilot.” Over time, auxiliary facilities within its vast reservation were dedicated to the top-secret flight-testing of Soviet MiGs, the standup of the first operational squadron of stealth fighters, and the hub of today’s tactical unmanned combat air vehicles.

On April 24, 1949, Harry and his pilot teammates landed at the desert outpost. Their efficiency and esprit de corps would help set the standard that has become the base’s hallmark.

Invigorated by their escapade at the Grand Canyon, the Tuskegee fighters were determined to prove that they were the best of the best in the Air Force.

The 332nd’s maintenance crews had arrived a day earlier via a C-47 transport. Their senior officer, Captain James T. Wiley, met with the event’s planning group, which included base officials. He had looked forward to these planning sessions, but he received belittling treatment. The higher-ups acted as though the “Negroes” had no chance of winning, and thus they did not take the 332nd’s team seriously.

As an original member of the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the first all-black flying combat unit, Wiley wasn’t going to take that snub lightly. He turned all his energies to motivating his armorers, communication specialists, mechanics, and crew chiefs to do their utmost. A short time later, Harry and his fellow team pilots conferred with base liaison personnel, experiencing a reception similar to Captain Wiley’s. But as with their maintenance chief, the cold shoulder only strengthened the pilots’ resolve to win.

For a week the teams familiarized themselves with the gunnery ranges and readied themselves for going game-on. The pilots and maintainers who had come from across the nation to prove their skills could sense the competitive spirit in the air. The 332nd’s team members buoyed each other as the May 2 start date neared; any butterflies in the pits of their stomachs were banished by cool self-assurance. Harry, for his part, was raring to get on with the competition, eager to show what he and the other Tuskegee Airmen could do.

Because Nevada’s scorching midday temperatures cause the air to roil in waves of convective heating, all competition flights commenced at the crack of dawn. The early start time meant that maintenance crews had no option but to labor through the night to prepare the planes for the demanding sorties. Even today, seven decades later, Harry can hardly find words to express the gratitude for his team’s maintainers.

According to Harry and the team’s other pilots, the enlisted personnel who traveled from Lockbourne to service the aircraft were the unsung heroes of the competition. The 332nd’s ground crews, like champion pit crews in motor racing, swarmed around the machines under their charge when they returned to the ramp at mid-morning. Diagnostics ensued, and the mechanics used the cool evenings to fine-tune the planes, continuing their work almost nonstop until flying resumed the next morning at sunrise.

The competition’s jet class included venerable F-80 Shooting Stars and newer F-84 Thunderjets. Jets were clearly the cutting edge, but the Air Force’s fleet recapitalization was taking time. Thus many units still flew conventional fighters, some that were even war surplus. The Tuskegee Airmen’s F-47 Thunderbolts were set to face F-51 Mustangs and F-82 Twin Mustangs. (In Air Force nomenclature, the “P” for pursuit had changed to “F” for fighter.)

To even the playing field, the F-47s, each with eight wing-mounted guns, had two guns disabled, leaving six in operation. This matched the six guns of the other propeller-driven fighters in the meet.

On May 2, the event formally got underway with the aerial gunnery contest, in which participants fired at twenty-by-six-foot wire-mesh sleeves towed behind medium bombers. As everyone had hoped, the sky remained clear for the duration of the meet. Because the 332nd was assigned to Ninth Air Force at the time and because that parent organization was tasked with tactical missions such as ground attack in support of infantry and had overseen meticulous training of its constituent fighter groups, it was to be expected that Harry and his teammates would score high in the parts of the competition that involved surface targets.

Conversely, it was expected that teams from other units would dominate the competition’s air-to-air component. Yet in the aerial gunnery category, one of Harry’s colleagues, Captain Temple, got the highest score. It was a terrific omen!

Early in the competition, the 332nd’s team was patched into a call from an all-black elementary school in the area. The segregated student body and faculty reflected the racial division of the public education system of the time. The school’s principal, who had heard that a contingent from the Air Force’s black flying unit was in town for the meet, requested that “one of the colored pilots” come to speak at the school.

Harry gladly accepted the invitation. The afternoon appearance would temporarily take his mind off the consuming challenge in the skies over Frenchman Flat and act as a tension-reliever. The memory of the principal ushering him into a packed gymnasium remains fresh. The children were spellbound by a black fighter pilot in flight suit with rank, insignia, and wings.

Here was the real thing, a living legend—one of the Tuskegee Airmen—gracing the school with an in-person visit. The principal introduced Harry by reading from a one-page resume that had been handed to him, announcing that the school’s guest had flown forty-three fighter combat missions and scored three air-to-air victories against the most formidable version of the Luftwaffe’s Focke-Wulf Fw 190, for which he had received the Distinguished Flying Cross. Now, the principal explained, Harry was taking a break from flying a high-performance fighter in a competition with Air Force pilots from around the country at the air base north of town.

The students greeted their guest warmly. They sat in silence, hanging on Harry’s every word. It occurred to Harry that he was a kind of Bessie Coleman spreading the “gospel” of aviation in the jet age.

Scanning the faces of the students arrayed before him, Harry wanted with all his heart to make a positive impression and to plant the seeds of an aviation future. In his soft-spoken style, he offered insight into his wartime experience and the Air Force flying life. He talked about the planes he flew and the teamwork that made it all possible.

None of it came easily, he told the students; one had to work at making it come true. But there were rewards—camaraderie, a sense of self-worth, and the knowledge of serving a cause greater than any one person. The gist of his message was that the same opportunity he had experienced could be theirs as well.

The audience of youngsters expressed their regard with an avalanche of applause. Harry wrapped up his presentation by inviting the classes to the air show scheduled at the conclusion of the gunnery meet. The principal stepped close to Harry and said, loudly enough for the students to hear, “We’ll be there!”

The outpouring of support touched Harry’s heart. He gained new strength from the visit and mused that it might have done as much if not more for him as it had done for the students who heard his talk. Immensely thankful for the time with the students, he was soon on his way back to the base to rejoin his teammates in the competition.

The next day the focus turned to ground targets, where it would remain for the rest of the meet and where Harry’s team expected to excel. In the panel gunnery contest pilots swooped in low over the sagebrush, aiming their machine-gun fire at the bull’s-eye painted in the middle of a square ten-by-ten-foot easel-mounted target. Despite the early morning start, the air was already unsettled at the lower altitudes.

Harry and his teammates were rocked by the turbulence, but they thought the F-47N gave them the advantage because it had been designed to be such a dependably stable gun platform. In fact, trying to hold their fighters steady during the runs at the target in the bedeviling air proved to be a chore for the Thunderbolt team. Given the rough air, the 332nd’s pilots put in a credible performance. Harry felt especially good, since his score topped those of his teammates.

But when all the competing panel gunnery scores were posted, Harry and his colleagues were stunned to find that the team from the 82nd Fighter Group, flying F-51s, had outshined everyone else, with remarkably high scores achieved by two of its three pilots. Harry realized that if any of the other teams was going to pull ahead, it was likely to be the talented one from the 82nd. For the moment, though, the 332nd’s team held a slight lead in the overall competition, so Harry and his teammates were still feeling good about their prospects.

Then, at a time when cautious optimism was percolating throughout the team, tragedy struck. As Harry remembers it, one of the 332nd’s maintenance members, Staff Sergeant Kenneth Austin, had yearned to ride in a fighter during the dive-bombing contest. The only type that could accommodate him was the Twin Mustang because of its second cockpit. The unusual aircraft, allowing two pilots to share the workload during long flights, had been introduced shortly after World War II. (In time the right cockpit would be changed into a radar observer’s position.)

During the meet, the right cockpit was usually left vacant, but Staff Sergeant Buford Johnson of the 332nd had already been treated to a dive-bombing run in one of the dual-cockpit fighters. So Sergeant Austin was also approved for a ride in an F-82’s right cockpit, with the pilot to fly from the left cockpit.

First Lieutenant Ralph M. Tibbetts of the 27th Fighter Group took off with Sergeant Austin as his passenger and headed to the range. The details of what happened next are remembered differently by different observers who were there, but in any case the outcome was tragic. According to Harry, “On its first dive, the F-82 smashed into the ground,” killing the two men on board instantly.

It was later determined by the official accident inquiry that the pilot had misjudged his altitude. The F-82, pitched at a thirty-degree angle, kept bearing down on the target laid out neatly on the desert floor. When finally, at only 150 feet from the ground, the aircraft began to pull up, it was too late to break the downward inertia. The plane’s twin fuselages mushed into the desert surface, igniting into a fireball.

The decision was made to carry on with the meet. The participants who had combat experience, like Harry, had known the feeling of having to proceed when friends were lost. Still, the loss suffered by the 332nd’s team was a hard burden to bear. They had come so far and now this—the death of a team member. The incident dampened the team’s spirit, and the scores tallied for the dive-bombing contest, which was underway, reflected that reality. Each member hit only half the targets in their passes—a mediocre performance. Harry and the others would have to do better in the remaining contests if they hoped to salvage any chance of winning the overall competition in their class.

Meanwhile Captain Wiley—the head of the 332nd’s maintenance support team whose only response to the racial prejudice he had initially encountered on base had been to squeeze extra performance out of his men—sought a release, both from the stresses of working on the Thunderbolts without a day off during the competition and from his grief for his colleague. One night Wiley and a few of his enlisted men strolled into the casino of the Flamingo Hotel wearing their uniforms.

But the 332nd’s ground support team members didn’t get far before hotel security guards stopped them and told them to leave. Insult was added to injury when a racial taunt was hurled at them. As they were making their way to the door, one of the guards blurted out, “Keep moving!” The experience was humiliating, but the servicemen had run into such ridicule at other times in their lives. As the unwelcome visitors exited they held their heads high, refusing to be deprived of their personal dignity.

Air Force personnel knew that the service’s old system of segregation would soon be ended because of the pending implementation of President Truman’s Executive Order 9981. Harry was anxious to see the new day arrive. As he and his fellow Tuskegee Airmen could attest, prejudice still reared its ugly head in all too familiar ways both inside and outside the fence.

The 332nd’s team shook off the ill effects of their experiences both on the range and in town, for they had work to do. Skip bombing was next, and it happened to be the forte of Harry and his colleagues. Proficiency in this specialty required intensive practice—which the team members had had during exercises in the recent past at other air bases like Eglin.

The pilots of the 332nd’s team didn’t huddle together the way football teams do before a play, but they were unanimously committed to honoring the memory of their fallen teammate Kenneth Austin by pulling out all the stops to score high in the remaining contests. They were all feeling the “win one for the Gipper” sentiment—from the classic words of the dying George Gipp to Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne in 1920, reenacted in the 1940 film of Rockne’s life starring Ronald Reagan as Gipp. The football analogy was in keeping with Harry’s way of casting the 332nd’s team as the underdog: as he said, it was like Grambling going up against the Big Ten.

When the skip bombing scores were tallied for the day, the 332nd’s team had registered an extraordinary six hundred points, a perfect score across the board. That meant the team’s three pilots had hit the targets with each one of their eighteen bombs. It was a performance unmatched by any of the other teams in the skip bombing contest—or any other contest during the entire meet!

It was an exceptional showing, and it boosted the team’s confidence going into the air-to-ground rocketry, the sole remaining contest. In that contest, the 332nd’s team beat all the others, though with a combined score that fell slightly short of a clean sweep. Temple was eight for eight while Stewart and Harvey each hit seven out of eight.

It appeared that Temple was poised to finish in first place among the pilots in the conventional class. But, according to one account, First Lieutenant William W. Crawford of the 82nd Fighter Group was allowed to repeat runs on the course due to equipment failure that had plagued his F-51 during the original runs. The makeups were said to have allowed Crawford to edge ahead of Temple, giving Crawford the top ranking among all pilots in individual scoring for the conventional class and relegating Temple to second place.

The “redo” reportedly caused members of the 332nd’s team to grumble that any equipment failure on board an aircraft was a maintenance issue that did not justify second chances. Could the dispensation granted to the 82nd’s star performer have been driven by an ulterior motive? Was the Air Force simply unwilling to countenance a black pilot outperforming his white peers?

Harry has no recollection of Crawford benefiting from a second chance because of extenuating circumstances. In Harry’s version of events, Crawford came from behind in a flying performance that was “absolutely fantastic.” Rather than finding fault with the scoring, Harry believes that Crawford won the individual first-place honor fair and square, in a hard-fought contest that came down to the wire.

The controversy aside, Harry and his colleagues had eked out the winning team score in the propeller class with 536.588 points, having retained a narrow margin over their competitors from the 82nd Fighter Group, who came in second with 515.010 points, followed by the 27th Fighter Group’s team, the third-place finisher with 475.325 points. The Tuskegee Airmen, the underdogs, had come out ahead!

Harry and his teammates were ecstatic. It was further validation that black pilots and ground crewmen could perform as well as or better than their white counterparts.

In the jet class, the 4th Fighter Group’s team in F-80s commandingly outperformed the other six jet teams. Individual honors for first and second place went to 4th Fighter Group pilots First Lieutenant Calvin Ellis and Captain Vermont Garrison respectively. Harry was not surprised, because the 4th Fighter Group belonged to Ninth Air Force. Indeed, the 332nd and the 4th had sharpened their tactical air-fighting skills by training together at Eglin’s auxiliary fields in Florida. As Harry opined at the time and continues to believe, those days spent in intensive practice down in Florida’s panhandle explained why teams from the two fighter groups performed so well at the big meet in Nevada.

As a reflection of the dawning of the new era in race relations, some white pilots from the 4th Fighter Group invited Harry to come with them to the Flamingo Hotel’s casino. Probably because he was in their company, Harry had no problem roaming the hotel’s lobby and casino that night. Harry and the other pilots enjoyed the evening partying together for, as fellow aviators who jockeyed fiercely in the skies over Frenchman Flat, they had much more in common than not.

Before the fighter groups departed for home, the base hosted the air show, which was open to the public. The transient pilots, relieved of the pressures of the competition, could strut their stuff for the local residents who came out to see the exhibition. Harry’s team, like the others, was slated to perform a formation flyover.

While taxiing to the runway as part of a ceremonial procession, Harry caught sight of the classes from the elementary school where he had talked days earlier. They sat in the grandstands, excited to be watching the variety of Air Force planes parading in front of them.

Harry slipped off his helmet so that his newfound friends could recognize him. He waved, which drew their attention. The students rose to their feet with the principal and returned the wave enthusiastically. It was a testimonial to the esteem in which he was held by those to whom he had reached out. Harry relished the moment.

Within minutes, he and his teammates were airborne. When their turn came, they closed in on each other’s wings and dipped to the preassigned altitude to give the crowd an obliging look at their formation. With their radial engines synched, the power of their combined strength funneled back through the pilots’ grip on the control columns. Their formation flight was machinelike, scrupulous, precise.

As he flew over the desert base for the last time, it hit Harry viscerally: he and his teammates had been adjudged premier fighter pilots, the Air Force’s top guns, as it were. The consciousness of having achieved what a few short years ago would have been inconceivable imbued Harry with an extra measure of pride. It was like his first solo flight. He and his colleagues up in the air were riding on top of the world.

The meet’s official doings culminated at an awards banquet back at the Flamingo. Colonel Davis had flown in for the presentation. He would not be present to greet his men upon their return to Lockbourne because of a pending assignment at the Air War College at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama. So this was his way to say thanks and, on a more subdued note, to show support in the wake of the loss of one of the team’s members. Davis and the other black officers filtered into the hotel among clusters of white officers.

Each team sat at its assigned tables, and Davis joined his men at the head of one of the 332nd’s. The jet class was recognized first. The 4th Fighter Group’s pilots were called to the front to be pictured with their awards amid a round of clapping.

The main team prize was a three-foot-tall amphora-like trophy that would be shared by the winners of both the jet class and the conventional class. The pewter device was mounted on a solid block of teak wood with a bronze plaque on the front awaiting the inscription of the names of the winning teams and their pilots. The trophy was crowned by a silvery figurine with arms raised skyward.

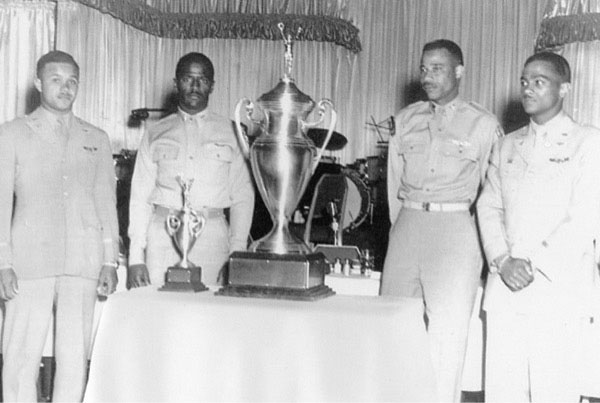

Winners in the propeller class of the 1949 gunnery meet celebrate with their trophies at the banquet in Las Vegas’s Flamingo Hotel. From left to right: alternate First Lieutenant Halbert L. Alexander, First Lieutenant James H. Harvey III, Captain Alva N. Temple, and Harry. U.S. Air Force via Harry Stewart Jr.

The words engraved on the body of the trophy were sparse, in the military tradition, but it was a case where less meant more: “United States Air Force—Fighter Gunnery Award.” A second, smaller trophy of a foot in height but bearing a similar design was also presented to each of the winning teams. The large trophy was to be safeguarded at the Pentagon, where subsequent winners would have their names added to plaques on the wooden base. The smaller trophy was to go to the home base of the winning team.

Next, as winners of the conventional class, the pilots of the 332nd’s team stepped to the front for their turn to be recognized with the trophies. The ballroom erupted into another round of clapping. The four Tuskegee Airmen, in the presence of their commander, received perhaps their highest honor—the admiration and respect of their peers.

On May 13, during the return flight to Lockbourne, the adrenaline finally started to drain. But when the air base came into sight, the team members perked up. They swept in fast and low, almost as if they were strafing their own field. Glancing at the rows of airmen below who had been assembled to welcome them home, the pilots waited until they reached the airfield’s midpoint and then pulled up and over into separate victory rolls!

The winners’ welcome home! On the team’s return to Lockbourne Air Force Base after their triumphant performance at the gunnery meet, the 332nd’s leadership made sure the returning pilots would know how much their success was appreciated. Note the honor guard cordon and the band on the tarmac as service personnel and family members watch from the edge of the parking apron, May 13, 1949. U.S. Air Force via Harry Stewart Jr.

Buzzing Lockbourne was technically a no-no. Colonel Davis ordinarily insisted on strict adherence to the regulations and frowned on stunting. But this was one of the rare times when, even after Davis heard what happened, the pilots who had indulged their fancy enjoyed impunity.

Delphine and Harry together again on the ramp at Lockbourne, May 13, 1949, evincing an infectious ebullience and imparting a sense that goodness can win out, that hope is not an illusion, and that dreams can come true. U.S. Air Force via Harry Stewart Jr.

On the ramp, the team’s pilots were treated like royalty. The 332nd’s band blared out lively music as each of the returning pilots marched through the saluting honor guard cordon. Harry and his flying teammates received a welcome worthy of heroes. They had done more than simply uphold the stature of the Tuskegee Airmen. By carving another notch in their unit’s string of achievements, they had added to its already awe-inspiring reputation.

Harry felt joy, for he had not let the members of his unit down; he had done them proud. And he had another reason to be joyful. When the returning F-47s had announced their arrival at Lockbourne with aerobatic maneuvers, Delphine was on the tarmac waiting to greet Harry. The couple posed for photographs. Harry, grinning smartly in his flight suit, and Delphine, mirroring her husband’s elation, together emitted an infectious ebullience that imparted a sense that goodness can win out, that hope is not an illusion, and that dreams can come true.