Chapter Sixteen

KEEPING THE DREAM ALIVE

I’ll fly away, O Glory, I’ll fly away.

—Albert E. Brumley, “I’ll Fly Away”

From its founding in 1987, the Tuskegee Airmen National Museum in Detroit was envisioned as a living testament to the flying accomplishments of the country’s first African American military pilots. This meant having a flight academy to inspire the city’s young people. As previously mentioned, when word came in 2002 that the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs was going to divest itself of some of its Schweizer motor-gliders, the museum requested and received three of the aircraft.

Harry’s flying had languished; work and family commitments had taken precedence, crowding out one of the things he loved to do. In 2004 that would change. He was asked if he wanted to go for a ride in a restored P-51, the type he had flown in combat during World War II.

It had been fifty-nine years since his last flight in a Mustang, and the experience of being in the cockpit again, soaring like the fighter pilots of old, reignited the wonder he had known. A short time later, he described his experience: “When I got in the plane and flew, I was bitten by the flying bug again.” In March 2005, he linked up with an instructor and refreshed his dormant skills, earning a glider rating at the same time.

Operating out of the city’s Coleman A. Young Municipal Airport, Harry started giving rides to youngsters in the museum’s motor-gliders. He hoped to kindle in his young passengers the same passion that he had had for flight when growing up near New York’s LaGuardia Airport. The museum’s leaders, for their part, were thrilled to have an original Tuskegee Airman flying the motor-gliders; they had Harry’s name emblazoned on one of them.

By the fall of 2007, Harry was eighty-three years old, and he reluctantly decided the time had come to ground himself. In the two years that he had participated in the museum’s aviation program, he had personally introduced scores of children to the joys of flight. He gave many their first plane rides.

After a ride in a restored P-51, Harry had found his first love again. In former Air Force Academy motor-gliders operated by the Tuskegee Airmen National Museum at Coleman A. Young Municipal Airport in Detroit, Harry introduced young people to their first plane rides, hoping to instill in them a sense of the magic of flight that he had experienced as a youngster watching planes at LaGuardia and as a cadet learning stick-and-rudder technique at Tuskegee. Harry Stewart Jr.

After taking off, he often steered north to sparsely used airspace underlain by virgin pastures and verdant farmlands, which presented a stark contrast to the daily sight-picture taken in by the program’s inner-city youth. At cruise altitude, while enveloped by the fresh breezes wafting in from over the blue waters of Lake Huron, Harry liked to pull the long wing of the motor-glider through graceful maneuvers that he had learned a generation ago in the skies above Tuskegee, sharing the liberating force—the magic—of the flyer’s world with his onboard companions.

Museum officials, led by president Brian R. Smith, had often ruminated about the museum one day having each of the aircraft types flown by the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II, starting with the Stearman biplane trainer all the way through the red-tailed fighters. In 2008, they made contact with the owner of one of only two flyable advanced trainers known to have been stationed at Tuskegee Army Airfield during the war. Negotiations ensued, and by the next year a deal was struck to store the plane at the museum’s hangar in Detroit. In September 2010, the museum consummated the purchase.

North American Aviation AT-6C, serial number 42-48884, had rolled off the assembly line in Dallas and been handed over to the Army Air Forces on March 27, 1943. It was promptly pressed into service as an advanced trainer at Tuskegee, where it remained for the duration of the war except for a deployment in June–July 1945 to Eglin Army Airfield in Florida. Harry checked his records, and while it’s not certain from the weathered logbook’s notations, indications are that he almost certainly flew this ship back when he was a cadet.

After the war, the plane hopscotched around the country, with postings at bases in Kansas, Tennessee, and New Hampshire. At one point it even wound up back in Alabama, assigned to the Air University at Maxwell Army Airfield. In January 1951 the trainer went to the North American Aviation plant at Downey, California, where it was remanufactured to the standard of a later model. On May 7, 1951, it was handed back to the Air Force as a T-6G with serial number 49-3292.

The rebuilt plane was then used by flight instruction contractors under Air Training Command’s aegis in Georgia and Missouri. In mid-1955 it was flown to the sprawling desert storage area at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona. Piston-powered taildraggers had little relevance to the Air Force a decade after the war, so in January 1956 the well-worn trainer was sold off as surplus property. For more than a half-century it plied the skies in private hands, until finally returning to the hands of some of those who had stamped it with its unique historical character.

In the spring of 2009, the Tuskegee Airmen National Museum in Detroit took delivery of one of only two still flyable AT-6 advanced trainers that had been used at Tuskegee Army Airfield during World War II. Harry rode along on the last leg of the delivery flight, helping to guide his old trainer to its new home. Sitting behind ferry pilot Bill Shepard, Harry flashes the victory sign, a poignant reference to the campaign to achieve the Double V—victory against totalitarianism abroad and racism at home. In subsequent years, while in the company of the plane on the air show circuit, Harry has delighted in explaining that he was “one of the luckiest people in the world to be able to fly this great airplane.” Tuskegee Airmen National Museum

In connection with the plane’s museum delivery flight from Oshkosh, Wisconsin, to Detroit in spring 2009, arrangements were made for Harry to fly with the ferry pilot, Bill Shepard, on the final leg from Jackson, Michigan. On this ship’s wings Harry had been baptized in the ocean of air more than six decades before. As he wrapped his fingers around the control stick, memories of old glories came to mind. For much of the flight and for a time afterwards, Harry beamed like he was one of the youngsters he had taken on a motor-glider ride.

The “old girl,” as he referred to the antique, hadn’t changed fundamentally in all the intervening years. She remained an honest lady who, if handled respectfully, would reciprocate the favor. And in the half-hour or so that Harry guided his long-separated mistress to her new home, his flight retraced a familiar trajectory—the course that allows for the dream that anything is possible.

Starting with the 2011 flying season, the rare aircraft has been displayed at a succession of air shows and fly-ins, frequently showcased in the premier exhibit space in deference to its historical significance. When time and health permit, Harry accompanies it, standing proudly alongside his ship. When bystanders approach with questions about his flights in it long ago, a smile invariably lights his face. He has been heard explaining, with a twinkle in his eyes, that he was “one of the luckiest people in the world to be able to fly this great airplane.”

But even before Tuskegee there was LaGuardia. As a fifteen-year-old in love with aviation and growing up in the Corona section of Queens, Harry was at the airport on the occasion of its renaming in honor of New York’s mayor in 1939. He stood on the ramp in front of a shiny all-metal airliner decked out in the markings of Transcontinental & Western Air, the precursor of Trans World Airlines, or TWA. The next spring, he watched from LaGuardia’s fence as large flying boats, the exquisite Pan Am Clippers, launched from the Marine Air Terminal to destinations across the Atlantic.

The TWA and Pan Am transports were tantalizing examples of a new age in commercial air transportation. For an impressionable adolescent they were the impetus for dreams of worlds awash in adventure. With tears in her eyes, Harry’s junior high school history teacher and guidance counselor had warned him not to get his hopes up. And indeed, when he tried to apply—as a decorated air combat veteran—to the airlines whose silver ships had lit his passion for flight, they turned him down on the spot.

But the story did not end there. The offensive employment practices at the airlines eventually changed with the times, spurred on by civil rights organizations promoting legal and legislative protections against discrimination. Also, private citizens stepped forward. Trailblazers included Perry H. Young Jr., who was hired in 1956 as the first black pilot for New York Airways, the commuter helicopter airline. Two years later, Ruth Carol Taylor was hired as Mohawk Airlines’ first black flight attendant. A major breakthrough occurred in 1965 when Marlon D. Green, a black pilot, won a protracted lawsuit against Continental Airlines to become one of the company’s pilots.

As things unfolded, Pan Am went bankrupt in 1991. Its vaunted transatlantic routes, the ones pioneered by the famous Clippers that had fueled Harry’s dreams of being a globe-trotting airline pilot, were taken over by Delta Air Lines in that year. And five years earlier, Delta had purchased Western Airlines, which could trace its origins to a 1930s offshoot of TWA. TWA itself went bankrupt in 2001 and was absorbed by American Airlines.

Both Delta and American are proud of their heritage airlines, Pan Am and TWA. American even maintains one of its aircraft in TWA heritage livery. The history is important, in part because many airline employees believe what they do is more than just a job.

More than seventy years after Harry’s dream of flight was born at LaGuardia’s fence, friends of his asked the two successor airlines if honorary captain’s wings could be awarded to him, given his distinguished military flying career and the unfortunate refusal of the legacy carriers to accept his application to fly for them. Delta was the first to agree.

On February 19, 2015, Harry was flown to Delta’s headquarters in Atlanta for the presentation. The honorary captain’s wings were accompanied by a typed tribute and a plaque reading, “In Recognition of Achievement in Aviation/Presented to: Honorary Delta Captain Harry Stewart.”

The accompanying tribute was on Delta letterhead. It recited Harry’s career highlights and included his military decorations. It concluded:

Your courage, hard work and perseverance are traits we look for when training Delta pilots and promoting them to the position of Captain. Be it known to all those present that Lt Col Harry Stewart, USAF, Ret. is hereby conferred the title of Honorary Delta Captain.

On behalf of Delta’s 12,000 pilots, we are honored and humbled to call you one of our own.

The tribute was signed by Captain Jim Graham, Delta’s vice president of flying operations and chief pilot. In August 2018, American Airlines followed Delta’s lead and announced that it would award honorary captain’s status not only to Harry but to all the surviving Tuskegee Airmen, in recognition of their selfless service to the country under exceptionally burdensome circumstances. During Black History Month, February 2019, the airline sent individualized certificates designating Harry and each of his surviving colleagues as an “Honorary American Airlines Captain.”

Harry held the document in its leather diploma-style cover, peering at it with a gleam in his eyes. The certificate referred to his “having served with distinction as one of the original Tuskegee Airmen” and noted that it was awarded as evidence of his “attaining a special place of high honor and as a sign of appreciation from the more than 130,000 American Airlines team members around the world.” It was signed by Kimball Stone, American Airlines’ senior vice president of flight operations and the Integrated Operations Center.

The magnitude of American Airlines’ transformation from its offhand acceptance of the industry’s prevailing attitudes of the mid-twentieth century can be seen in the top management’s quick and unequivocal reaction in recent times to isolated incidents involving passengers of color. On October 25, 2017, CEO Doug Parker sent a letter to his company’s employees stating: “We do not and will not tolerate discrimination of any kind.”

Today many African Americans, members of other minority groups, and women are acutely aware that their opportunity to fly for the airlines was forged through individual acts of courage by trailblazers like Harry. By refusing to be intimidated and by being unafraid to stare the evil of prejudice in the face, Harry was one of the steadfast souls who opened up the staircase to the skies for people of all colors and creeds and walks of life.

Harry and his fellow Tuskegee Airmen never stopped dreaming, never stopped believing that one day America would waken to the promise of equal opportunity for all citizens. More than three-quarters of a century since the little boy from Queens went to the local airport with the improbable dream of captaining the exquisite and alluring TWA and Pan Am airliners, those airlines, in their modern form, had blessed his dream. He is now Captain Stewart!

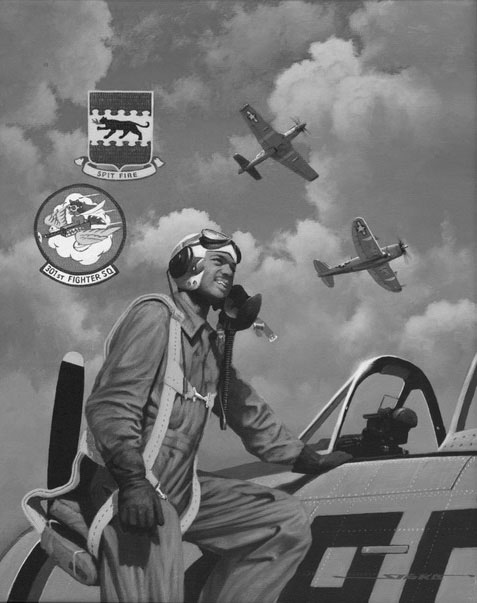

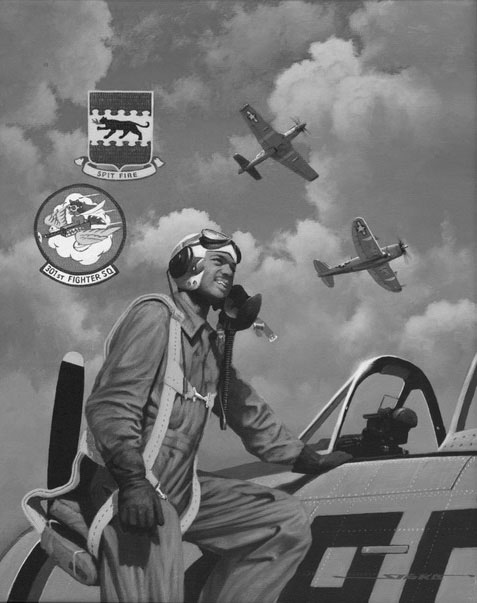

Soaring to glory! Aviation artist Stan Stokes captured Harry on the wing of a postwar F-47N, gazing skyward. Above is his red-tailed P-51D Little Coquette and the P-47, in which he had the bulk of his fighter lead-in training. To the left are the patches of the 332nd Fighter Group and the 301st Fighter Squadron. Palm Springs Air Museum

In reaching for the heavens and defying gravity, Harry advanced the cause of freedom. The successes that stemmed from his gallantry and quiet dignity are reminders that no one needs to accede any longer to the encumbrances that he encountered throughout his flying life. Instead, as the astute commentator Walter Lippmann wrote in praise of Amelia Earhart and her ilk, who had pushed the proverbial envelope ever farther in flight’s golden age, in the dust of which we are made “there is also fire, lighted now and then by great winds from the sky.”

Harry helped to kindle that fire, which has illuminated the way for all who fly!