CHAPTER 18

Symptoms and Diagnosis of Digestive Disorders

Disorders that affect the digestive (gastrointestinal) system are called digestive disorders. Some disorders simultaneously affect several parts of the digestive system, whereas others affect only one part or organ.

Symptoms

Some symptoms, such as diarrhea, constipation, bleeding from the digestive tract, regurgitation, and difficulty swallowing, usually suggest a digestive disorder. More general symptoms, such as abdominal pain, flatulence, loss of appetite, and nausea, may suggest a digestive disorder or another type of disorder.

Indigestion is an imprecise term that is used by different people to mean different things. The term covers a wide range of symptoms, including dyspepsia, nausea and vomiting, regurgitation, and the sensation of having a lump in the throat (globus sensation).

Bowel (intestinal) function varies greatly not only from one person to another but also for any one person at different times. Most people find it easiest to move their bowels in the morning. The urge tends to be strongest about 30 to 60 minutes after first eating in the morning. Bowel function can be affected by diet, stress, drugs, disease, and even social and cultural patterns. In most Western societies, the normal number of bowel movements ranges from 2 or 3 a week to as many as 2 or 3 a day. Changes in the frequency, consistency, or volume of bowel movements or the presence of blood, mucus, pus, or excess fatty material (oil or grease) in the stool may indicate a disorder.

ABDOMINAL PAIN

Abdominal pain is common and often minor. Severe abdominal pain of rapid onset, however, almost always indicates a significant problem. The pain may be the only sign of the need for surgery and must be attended to swiftly. Abdominal pain is of particular concern in people who are very young or very old and those who have human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or are taking drugs that suppress the immune system. Older adults may have less abdominal pain than younger adults, and, even if the condition is serious, the pain may develop more gradually. Abdominal pain also affects children, including newborns and infants—who cannot communicate the cause of their distress.

Causes

Pain can arise from any of several causes, including infection, inflammation, formation of sores (ulcers), perforation or rupture of organs, muscle contractions that are uncoordinated or blocked by an obstruction, and blockage of blood flow to organs.

Examples of disorders that are immediately life threatening, requiring rapid diagnosis and surgery, include a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, perforated stomach or intestine, blockage of blood flow to the intestine (mesenteric ischemia), and ruptured ectopic pregnancy (see page 1644). Disorders that are also serious and nearly as urgent include intestinal obstruction, appendicitis, and acute inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis). Peritonitis is pain caused by inflammation of the lining of the abdominal cavity (peritoneum), which occurs with many disorders that result in inflammation or infection of abdominal organs (such as appendicitis and diverticulitis) or leakage of intestinal contents into the abdomen (such as a perforated ulcer).

Sometimes, disorders outside the abdomen also produce abdominal pain. Examples include heart attack, pneumonia, and twisting of the testes (testicular torsion). Other problems that cause abdominal pain include diabetic ketoacidosis, porphyria, sickle cell disease, and certain bites and poisons (such as a black widow spider bite, heavy metal or methanol poisoning, and some scorpion stings).

ABDOMINAL PAIN IN NEWBORNS, INFANTS, AND YOUNG CHILDREN

| CAUSE OF PAIN | DESCRIPTION | COMMENTS |

| Meconium peritonitis | Inflammation and sometimes infection of the abdominal cavity and its lining (peritonitis) caused by a perforation in the intestine and leakage of meconium, the dark green fecal material that is produced in the intestines before birth | Occurs while infants are still in the womb or shortly after birth |

| Pyloric stenosis | A blockage at the stomach outlet (duodenum) | Forceful (projectile) vomiting occurs after feedings Usually begins between birth and 4 months of age |

| Esophageal webs | Thin membranes that grow across the inside of the upper one third of the esophagus from its surface lining (mucosa) | Solids are difficult to swallow |

| Volvulus | Twisting of a loop of the intestines | Causes intestinal obstruction and cuts off blood supply to intestines Vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal swelling, and episodic and excessive crying (colic) are common |

| Imperforate anus (anal atresia) | Narrowing or blockage of the anal opening | Normally detected by doctors when infants are examined after birth and usually requiring immediate surgery |

| Intussusception | The condensing and overlapping (telescoping) of one portion of the intestine into another | Causes obstruction of the bowel and blockage of its blood flow, sudden pain, vomiting, bloody stools, and fever Typically affects children between the ages of 6 months and 2 years |

| Intestinal obstruction | A blockage that completely stops or seriously impairs the passage of intestinal contents | Commonly caused by a birth defect, meconium, or volvulus in newborns and infants |

| Symptoms vary by type of obstruction but may include cramping pain in the abdomen, bloating, disinterest in eating, vomiting, severe constipation, diarrhea, and fever |

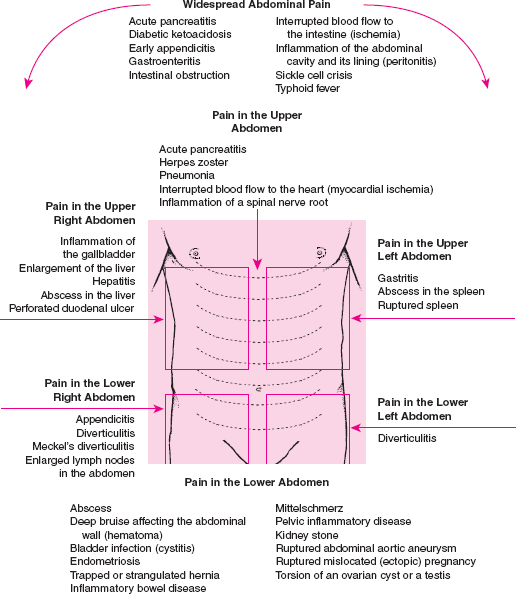

Causes of Abdominal Pain by Location

Evaluation

Sometimes, the nature and location of the pain help doctors identify the cause. Pain that comes and goes in waves suggests an organ is blocked, which might occur with gallstones, kidney stones, or intestinal obstruction. Pain produced by a peptic ulcer is often characterized as burning. Pain that accompanies diverticulitis is often limited to the lower left abdomen, whereas the pain of peritonitis is frequently felt throughout the abdomen. Pancreatitis often produces pain that is worsened by rolling over in bed and is relieved somewhat by sitting upright and leaning forward.

Often, the doctor must perform tests to help choose among several different causes suggested by the person’s symptoms and physical examination results. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan helps identify many, but not all, causes of abdominal pain. Blood and urine tests are frequently obtained. An ultrasound is helpful if gynecologic disorders are suspected.

Treatment

The specific cause of the pain is treated. Until recently, doctors thought that it was not wise to give pain medicine to people with severe abdominal pain until a diagnosis was made because the medicine might mask important symptoms. Pain relievers are often now be given while tests are in progress.

BLEEDING FROM THE DIGESTIVE TRACT

Bleeding may occur anywhere along the digestive tract, from the mouth to the anus. Blood may be visible in vomit (hematemesis). When blood is vomited, it may be bright red if bleeding is brisk and ongoing. Alternatively, vomited blood may have the appearance of coffee grounds if bleeding has slowed or stopped, due to the partial digestion of the blood by acid in the stomach.

Blood may also be passed from the rectum, either as black, tarry stools (melena), as bright red blood (hematochezia), or in apparently normal stool if bleeding is less than a few teaspoons per day. Melena is more likely when bleeding comes from the esophagus, stomach, or small intestine. The black color of melena is caused by blood that has been exposed for several hours to stomach acid and enzymes and to bacteria that normally reside in the large intestine. Hematochezia is more likely when bleeding comes from the large intestine, although it can be caused by very rapid bleeding from the upper portions of the digestive tract as well.

Serious and sudden blood loss may be accompanied by a rapid pulse, low blood pressure, and reduced urine flow. A person may also have cold, clammy hands and feet. Severe bleeding may lead to reduced flow of blood to the brain, causing confusion, disorientation, sleepiness, and even extremely low blood pressure (shock). Slow, chronic blood loss may cause symptoms and signs of anemia (such as weakness, easy fatigue, pallor, chest pain, and dizziness).

COMMON CAUSES OF GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

| REGION | CAUSE |

| Upper digestive tract | Doudenal ulcer Erosions of esophagus, stomach, or duodenum Esophageal varices Stomach ulcer |

| Lower digestive tract | Abnormal blood vessels Anal fissures Colon cancer Colon polyps Diverticulosis Inflammatory bowel disease Internal hemorrhoids Large-bowel inflammation from radiation or poor blood supply |

Causes

Bleeding can have many causes, including peptic ulcers; abnormal connections between the arteries and veins of the intestines (arteriovenous malformations); dilated veins in the esophagus (esophageal varices); irritation from use of certain drugs, such as aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); inflammatory bowel disease; small balloon-like sacs in the wall of the colon (diverticulosis); and cancer.

Bleeding from any cause is more likely, and potentially more severe, in people who have chronic liver disease or hereditary disorders of blood clotting and in those who are taking certain drugs. Drugs that can cause bleeding include anticoagulants (such as heparin and warfarin) and those that affect platelet function (such as aspirin and certain other NSAIDs and clopidogrel).

Evaluation

The doctor tries to find out exactly where the bleeding is coming from, how rapid it is, and what is causing it. The person’s symptoms and physical examination (including a digital rectal examination to feel for masses and test the stool for blood) sometimes suggest a cause and location and may suggest which tests are needed.

If the person has vomited blood or dark material (which may represent partially digested blood), the doctor passes a small, hollow plastic tube through the person’s nose down into the stomach (nasogastric tube—see page 131) and suctions out the stomach contents. Bloody contents indicate active bleeding, and dark material may indicate that bleeding is slow or has stopped. Sometimes, there is no sign of blood even though the person was bleeding very recently. A nasogastric tube is also inserted in anyone who has not vomited but has passed a large amount of blood from the rectum (if not from an obvious hemorrhoid) because this blood may have originated in the upper digestive tract. The nasogastric tube is usually left in place until it is clear that all bleeding has stopped.

If the nasogastric tube reveals signs of active bleeding, or the person’s symptoms strongly suggest the bleeding is originating in the upper digestive tract, the doctor usually performs upper endoscopy. Upper endoscopy is a visual examination of the esophagus, stomach, and the first segment of the small intestine (duodenum) using a flexible tube called an endoscope (see page 129). An upper endoscopy allows the doctor to see the bleeding source and often treat it. Similarly, colonoscopy (see page 129) is performed if symptoms suggest the bleeding is originating in the lower digestive tract, or if upper endoscopy does not reveal a bleeding site.

Rarely, endoscopy (both upper and lower) does not show the cause of bleeding. For such people, if bleeding is severe, doctors sometimes perform angiography or inject the person with red blood cells labeled with a radioactive marker. With the use of a special scanning camera, the radioactive marker can sometimes show the approximate location of the bleeding. If bleeding is slow, doctors may instead take x-rays after the person drinks liquid barium (see page 130). Another option is capsule endoscopy (see page 130). Capsule endoscopy is especially useful in the small intestine, but it is not very useful in either the colon or stomach, because these organs are too big to get good pictures of their inner lining.

Doctors also obtain blood tests. The person’s blood count helps indicate how much blood has been lost. A low platelet count is a risk factor for bleeding. Other blood tests include prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and tests of liver function, which help detect problems with blood clotting.

Treatment

People with sudden, severe blood loss require intravenous fluids and sometimes an emergency blood transfusion to stabilize their condition. Those with blood clotting abnormalities may require transfusion of platelets or fresh frozen plasma or injections of vitamin K.

Most gastrointestinal bleeding stops on its own. If it does not, the doctor can often stop it during endoscopy by using an electrocautery device, laser, or injections of certain drugs. Bleeding polyps can be removed with a wire snare or other device. If these methods do not stop the bleeding, the person may require surgery.

CHEST OR BACK PAIN

Pain in the middle of the chest or upper back can result from disorders of the esophagus or from disorders of the heart or aorta. Symptoms may be similar. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), caused by stomach acid splashing up into the esophagus, can produce a burning sensation or a tightness under the breastbone (sternum), which may resemble the pain of heart disease. Spasms of the esophagus and other esophageal muscle disorders can cause a severe squeezing sensation also resembling the pain of heart disease.

Some symptoms are more suggestive of esophageal disorders. Heartburn is a burning pain caused by GERD that rises into the chest and sometimes the neck and throat, usually after meals or when lying down. Heartburn is among the most common digestive symptoms in the United States. Discomfort that occurs only with swallowing also suggests an esophageal disorder. Chest discomfort that occurs routinely with exertion and goes away after a brief rest suggests a heart problem. However, because symptoms frequently overlap, and because heart disease is particularly dangerous, doctors often obtain a chest x-ray, electrocardiogram (ECG), and sometimes a cardiac stress test before doing tests to look for esophageal disease.

Treatment is usually given only when the cause is known, although people with very typical symptoms of GERD may be given a trial of acid-blocking drugs.

CONSTIPATION

Constipation is a condition in which a person has uncomfortable or infrequent bowel movements.

Constipation may be acute or chronic. Acute constipation begins suddenly and conspicuously. Chronic constipation may begin gradually and persists for months or years.

A person with constipation often or always produces hard stools that may be difficult to pass. The rectum may not feel completely empty. Bowel movements are likely to be infrequent. Many people believe they are constipated if they do not have a bowel movement (defecate) every day. However, daily bowel movements are not normal for everyone, and having less frequent bowel movements does not necessarily indicate a problem unless there has been a substantial change from previous patterns. The same is true of the color and consistency of stool; unless there is a substantial change, the person probably does not have constipation. Constipation is blamed for many symptoms (such as abdominal discomfort, nausea, fatigue, and poor appetite—although constipation can cause nausea and poor appetite) that are actually the result of other disorders (such as irritable bowel syndrome and depression). People should not expect all symptoms to be relieved by a daily bowel movement.

Complications: Straining during a bowel movement increases pressure on the veins around the anus and can lead to hemorrhoids. Straining also increases blood pressure, which, although temporary, may be extreme.

Constipation is one of the major risk factors for the development of diverticular disease. The walls of the large intestine are damaged by the increased pressure required to move small, hard stools. Damage to the walls of the large intestine leads to the formation of balloon-like sacs or outpocketings (diverticula), which can become clogged and inflamed.

Fecal impaction, in which stool in the last part of the large intestine and rectum hardens and blocks the passage of other stool, sometimes develops in people with constipation. This condition is particularly common among older people, pregnant women, and people with an inactive colon (colonic inertia). Fecal impaction leads to cramps, rectal pain, and strong but futile efforts to defecate. Often, watery mucus or liquid stool oozes around the blockage, sometimes giving the false impression of diarrhea. Fecal impaction can aggravate or further worsen constipation.

Overconcern with regular bowel movements causes many people to abuse their bowels with laxatives, suppositories, and enemas. Overusing these treatments can actually inhibit the bowel’s normal contractions and worsen constipation.

Causes

Constipation can result when the passage (transit) of stool through the large intestine is slowed by disease or certain drugs. Sometimes constipation is caused by dehydration or a low-fiber diet. Pain and mental disorders, such as depression, may also contribute to constipation. In many cases, however, the cause of constipation is unknown.

Slowed Transit of Stool: Constipation tends to occur when the passage of stool along the large intestine slows. Under normal circumstances, water is pulled from the stool as it passes through the large intestine. Slowed transit of stool allows the large intestine to pull more water from the stool, resulting in the hard, dry stools and difficult passage of stools that characterize constipation.

Drugs that can slow transit of stool include aluminum hydroxide (common in over-the-counter antacids), bismuth subsalicylate, iron salts, drugs with anticholinergic effects (such as many antihistamines and some antidepressants), certain antihypertensives, opioids, and many sedatives. Because physical activity helps the intestines move stool along, lack of activity tends to slow transit and lead to constipation. For this reason, people who are confined to bed because of illness often are constipated.

Disorders and diseases that can slow transit of stool include an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism), high blood calcium levels (hypercalcemia), and Parkinson’s disease. People with diabetes often develop a condition in which parts of the digestive system slow down. Other conditions, including poor blood supply to the large intestine and nerve or spinal cord injury, can also cause constipation by slowing transit.

In an extreme case of slowed transit, called colonic inertia, the large intestine stops responding to the stimuli that usually cause bowel movements: eating, a full stomach, a full large intestine, and stool in the rectum. A decrease in contractions in the large intestine or an insensitivity of the rectum to the presence of stool results in severe, chronic constipation. Colonic inertia often occurs in people who are older, debilitated, or bedridden, but it occasionally occurs in otherwise healthy younger women (and, much less commonly, in healthy younger men). Colonic inertia sometimes occurs in people who habitually delay moving their bowels or who have used laxatives or enemas for a long time.

Dehydration and Low-Fiber Diet: Dehydration causes constipation because the body tries to conserve water in the blood by removing additional water from the stool. Lack of fiber (the indigestible part of food) in the diet can lead to constipation because fiber helps hold water in the stool and increases its bulk, making it easier to pass.

Obstruction: Constipation is sometimes caused by obstruction of the large intestine. Obstruction can be caused by cancer, especially in the last portion of the large intestine, if a tumor blocks the movement of stool. People who previously had abdominal surgery may develop obstruction, usually of the small intestine, because of formation of bands of fibrous tissues (adhesions), which impede the flow of the stool.

Dyschezia: Dyschezia is difficulty in defecating caused by an inability to control the pelvic and anal muscles. Having a normal bowel movement requires relaxing the pelvic floor muscles (the muscles that support the bladder, uterus, and rectum) and the circular muscles (sphincters) that keep the anus closed. Otherwise, efforts to defecate are futile, even with severe straining. People with dyschezia sense the need

CAUSES OF CONSTIPATION

| CAUSE | EXAMPLES OR COMMENTS |

| Acute constipation | |

| Acute bowel obstruction | Twisting of a loop of intestine (volvulus), hernia, adhesions, fecal impaction |

| Ileus (temporary absence of the contractile movements of the intestinal wall) | Inflammation of the lining of the abdominal cavity (peritonitis), head or spinal trauma, bed rest |

| Drugs | Drugs with anticholinergic effects (antihistamines, some antidepressants, antipsychotics, antiparkinsonians, antispasmodics), metallic ions (iron, aluminum, calcium, barium, bismuth), opioids, general anesthesia |

| Chronic constipation | |

| Colon cancer | Often, constipation gradually worsens as tumor grows |

| Metabolic disorders | Diabetes mellitus, underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism), high levels of calcium in the blood (hypercalcemia), build up of toxic substances in the blood (uremia), porphyria (a group of disorders caused by deficiencies of enzymes) |

| Central nervous system disorders | Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, stroke, spinal cord injury or disease |

| Peripheral nervous system disorders | Hirschsprung’s disease, neurofibromatosis, autonomic neuropathy |

| Systemic disorders | Systemic sclerosis, amyloidosis, skin inflammation plus muscle inflammation and muscle degeneration (dermatomyositis), weakness and stiff muscles (myotonic dystrophy) |

| Functional disorders | Inactive colon (colonic inertia), irritable bowel syndrome |

| Diet | Low fiber, chronic laxative abuse |

to have a bowel movement but cannot. Even stool that is not hard may be difficult to pass.

Conditions that can cause dyschezia include pelvic floor dyssynergia (a disturbance of muscle coordination), anismus (a failure of the sphincter muscles to relax during defecation), rectocele (hernia of the rectum into the vagina), enterocele (bulging of the small intestine and the lining of the abdominal cavity between the uterus and the rectum or between the bladder and the rectum), rectal ulcer, and rectal prolapse (protrusion of the rectal lining through the anus).

Aging: Constipation is particularly common among older people. Age-related changes in the large intestine (see page 114) along with increased use of drugs, a low-fiber diet, and reduced physical activity tend to slow the transit of stool through the large intestine. Slowed transit is particularly common during periods of illness. The rectum enlarges with age, and increased storage of stool in the rectum allows hard stool to become impacted.

Pain and Psychologic Factors: Chronic pain and psychologic conditions, especially depression, are common causes of acute and chronic constipation. Changes in the levels of certain substances in the brain, such as serotonin, can affect the intestinal tract.

Evaluation

When constipation develops in someone who has not had it before, the doctor first looks for an easy explanation, such as a change in diet or physical activity or new use of a drug known to cause constipation. Then, the doctor may perform blood tests to check for an under-active thyroid gland (hypothyroidism) or high calcium levels in the blood (hypercalcemia), both of which can cause constipation. If there is any question about cancer as a cause, a colonoscopy is performed.

Prevention

Constipation is best prevented and treated with a combination of exercise, a high-fiber diet, an adequate intake of fluids, and the occasional use of laxatives.

When a potentially constipating drug has been prescribed, a laxative along with increased intake of dietary fiber and fluids help to prevent constipation.

Vegetables, fruits, and bran are excellent sources of fiber. Many people find it convenient to sprinkle 2 or 3 teaspoons of unrefined miller’s bran on high-fiber cereal or fruit 2 or 3 times a day. To work well, fiber must be consumed with plenty of fluids.

Treatment

When an underlying disorder is causing constipation, the disorder must be treated.

Dyschezia is not easily treated with laxatives. Relaxation exercises and biofeedback are effective for some people with pelvic floor dyssynergia. Surgery may be needed to repair an enterocele or a large rectocele.

Fecal impaction cannot be treated by modifying the diet or simply by taking laxatives. The hard stool usually has to be removed by a doctor or nurse using a gloved finger. Often an enema is given after the hard stool is removed.

Overzealous treatment, especially the long-term use of stimulant laxatives, irritant suppositories, and enemas, can lead to diarrhea, dehydration, cramps, or dependence on laxatives.

Laxatives: Many people use laxatives to relieve constipation. Some laxatives are safe for long-term use; others should be used only occasionally. Some are good for preventing constipation, others for treating it.

Bulking agents, such as bran and psyllium (also available in the fiber of many vegetables), add bulk to the stool. The increased bulk stimulates the natural contractions of the intestine, and bulkier stools are softer and easier to pass. Bulking agents act slowly and gently and are among the safest ways to promote regular bowel movements. These agents generally are taken in small amounts at first. The dose is increased gradually until regularity is achieved. People who use bulking agents should always drink plenty of fluids. These agents may cause problems with increased gas (flatulence).

Stool softeners, such as docusate, increase the amount of water that the stool can hold. Actually, these laxatives are detergents that decrease the surface tension of the stool, allowing water to penetrate the stool more easily and soften it. In addition, the slightly increased bulk that results from these drugs stimulates the natural contractions of the large intestine and thus promotes easier elimination. Some people, however, find the softened nature of the stool unpleasant. Stool softeners are best reserved for people who must avoid straining, such as people who have hemorrhoids or have recently had surgery.

Osmotic agents pull large amounts of water into the large intestine, making the stool soft and loose. The excess fluid also stretches the walls of the large intestine, stimulating contractions. These laxatives consist of salts or sugars that are poorly absorbed. They may cause fluid retention in people who have kidney disease or heart failure, especially when given in large or frequent doses. Osmotic agents that contain magnesium and phosphate are partially absorbed into the bloodstream and can be harmful to people who have kidney failure. Although a rare occurrence, phosphate laxatives taken by mouth have caused kidney failure. These laxatives usually work within 3 hours. They are also used to clear stool from the intestine before x-rays of the digestive tract are taken or before a colonoscopy is performed.

Stimulant laxatives contain irritating substances, such as senna and cascara. These substances stimulate the walls of the large intestine, causing them to contract and move the stool. Taken by mouth, stimulant laxatives usually cause a semisolid bowel movement in 6 to 8 hours, but they often cause cramping as well. As suppositories, stimulant laxatives often work in 15 to 60 minutes. Prolonged use of stimulant laxatives can create abnormal changes in the lining of the large intestine caused by deposits of a pigment (a condition called melanosis coli). Also, stimulant laxatives can become addictive, leading to the development of lazy bowel syndrome, which in turn causes the large intestine to become dependent on the laxatives. Therefore, stimulant laxatives should be used only for brief periods of time to treat constipation. They are useful for preventing constipation in people who are taking drugs that will almost certainly cause constipation, such as opioids. Stimulant laxatives are often used to empty the large intestine before diagnostic procedures are performed. A newer stimulant laxative, lubiprostone, works by making the large intestine secrete extra fluid, which makes stool easier to pass. Unlike other stimulant laxatives, lubiprostone is safe for prolonged use.

Enemas: Enemas mechanically flush stool from the rectum and lower part of the large intestine. Small-volume enemas can be purchased in squeeze bottles at a pharmacy. They can also be given with a reusable squeeze-ball device. However, small-volume enemas are often inadequate, especially for older people, whose rectal capacity increases with age, thus making the rectum more easily stretched. Larger-volume enemas are given with an enema bag.

Plain water is often the best fluid to be used as an enema. The water should be room temperature to slightly warm, not hot or cold. About 5 to 10 fluid ounces (150 to 300 milliliters) is gently directed into the rectum. (CAUTIO: Additional force is dangerous.) The water is then expelled, washing stool out with it.

Prepackaged enemas often contain small amounts of salts, often phosphates. Appropriate salts can also

DRUGS USED TO PREVENT OR TREAT CONSTIPATION

DRUGS USED TO PREVENT OR TREAT CONSTIPATION

| DRUG | SOME SIDE EFFECTS | COMMENTS |

| Bulking agents | ||

| Bran Polycarbophil Methylcellulose Psyllium |

Flatulence, bloating | Bulking agents generally are used to prevent or control chronic constipation. |

| Stool softeners | ||

| Docusate | Nausea (especially with syrup/liquid formulation) | Stool softeners may be used to treat constipation and are often used to help prevent it. |

| Osmotic agents | ||

| Lactulose Magnesium salts (magnesium hydroxide, magnesium citrate) Polyethylene glycol Sodium phosphate Sorbitol |

Cramps, flatulence (lactose, sorbitol) | Osmotic agents are better for treating constipation than for preventing it. |

| Stimulant laxatives | ||

| Bisacodyl Cascara Castor oi Lubiprostone Senna |

Abdominal pain (cramps); prolonged use can damage large intestine | Stimulant laxatives are not used if there is a possibility of an intestinal obstruction. Lubiprostone can be used for chronic constipation. |

be added to homemade enemas. They offer little advantage, however, to plain water.

The addition of small amounts of soap to the water (soap-suds enema) adds the stimulant laxative effects of soap. Soap-suds enemas are sometimes useful when plain water enemas fail, but they can cause cramping.

Many other substances, including mineral oil, are sometimes added to water-based enemas. However, they offer little advantage.

Very large-volume enemas, called colonic enemas, are rarely used in medical practice. Doctors use colonic enemas in people with very severe constipation (obstipation). Some practitioners of alternative medicine use colonic enemas in the belief that cleansing the large intestine is beneficial. Tea, coffee, and other substances are often added to colonic enemas but have no proven health value and may be dangerous.

DIARRHEA

Diarrhea is an increase in the volume, wateriness, or frequency of bowel movements.

The frequency of bowel movements alone is not the defining feature of diarrhea. Some people normally move their bowels 3 to 5 times a day. People who eat large amounts of vegetable fiber may produce more than a pound of stool a day, but the stool in such cases is well formed and not watery. Diarrhea occurs when not enough water is removed from the stool, making the stool loose and poorly formed. Diarrhea is often associated with gas, cramping, an urgency to defecate, and, if the diarrhea is caused by an infectious organism or a toxic substance, nausea and vomiting.

Diarrhea can lead to dehydration and a loss of electrolytes, such as sodium, potassium, magnesium, chloride, and bicarbonate, from the blood. If large amounts of fluid and electrolytes are lost, the person feels weak, and blood pressure can drop enough to cause fainting (syncope), heart rhythm abnormalities (arrhythmias), and other serious disorders. At particular risk are the very young, the very old, the debilitated, and people with very severe diarrhea. Diarrhea is a major cause of infant mortality in developing countries and results in many hospitalizations in the United States.

Causes

Normally, stool is 60 to 90% water. Diarrhea mainly occurs when the percentage is over 90%. Stool may contain too much water if it travels too quickly through the digestive tract, if certain components of the stool prevent the large intestine from absorbing water, or if water is being secreted by the large intestine into the stool. There are many different causes, including drugs and chemicals; infection with viruses, bacteria, or parasites (gastroenteritis—see page 145); some foods; stress; tumors; and chronic disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, and malabsorption syndromes.

Rapid passage (transit) of stool is one of the most common causes of diarrhea. For stool to have normal consistency, it must remain in the large intestine for a certain amount of time. Stool that leaves the large intestine too quickly is watery. Many medical conditions and treatments can decrease the amount of time that stool stays in the large intestine, including an overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism); Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (a condition of over-production of acid secondary to a tumor); surgical removal of part of the stomach, small intestine, or large intestine; surgical bypass of part of the intestine; and drugs such as antacids containing magnesium, laxatives, prostaglandins, serotonin, and even caffeine. Many foods, especially those that are acidic, can increase the rate of transit. Some people are intolerant of specific foods and always develop diarrhea after eating them. Stress and anxiety are also common causes.

Osmotic diarrhea occurs when certain substances that cannot be absorbed through the colon wall remain in the intestine. These substances cause excessive amounts of water to remain in the stool, leading to diarrhea. Certain foods (such as some fruits and beans) and hexitols, sorbitol, and mannitol (used as sugar substitutes in dietetic foods, candy, and chewing gum) can cause osmotic diarrhea. Also, lactase deficiency can lead to osmotic diarrhea. Lactase is an enzyme normally found in the small intestine that converts lactose (milk sugar) to glucose and galactose, so that it can be absorbed into the bloodstream. When people with lactase deficiency drink milk or eat dairy products, lactose is not digested. As lactose accumulates in the intestine, it causes osmotic diarrhea—a condition known as lactose intolerance. The severity of osmotic diarrhea depends on how much of the osmotic substance is consumed. Diarrhea stops soon after the person stops eating or drinking the substance. Blood in the digestive tract also acts as an osmotic agent and results in black, tarry stools (melena). Another cause of osmotic diarrhea is an overgrowth of normal intestinal bacteria or the growth of bacteria normally not found in the intestines. Antibiotics can cause osmotic diarrhea by destroying the normal intestinal bacteria.

FOODS AND DRUGS THAT CAN CAUSE DIARRHEA

| FOOD OR DRUG | INGREDIENT CAUSING DIARRHEA |

| Apple juice, pear juice, sugar-free gum, mints | Hexitols, sorbitol, mannitol |

| Apple juice, pear juice, grapes, honey, dates, nuts, figs, soft drinks (especially fruit flavors) | Fructose |

| Table sugar | Sucrose |

| Milk, ice cream, yogurt, frozen yogurt, soft cheese, chocolate | Lactose |

| Antacids containing magnesium | Magnesium |

| Coffee, tea, cola drinks, some over-the-counter headache remedies | Caffeine |

| Fat-free potato chips, fat-free ice cream | Olestra |

Secretory diarrhea occurs when the small and large intestines secrete salts (especially sodium chloride) and water into the stool. Certain toxins—such as the toxin produced by a cholera infection or during some viral infections—can cause these secretions. Infections by certain bacteria (for example, Campylobacter) and parasites (for example, Cryptosporidium) can also stimulate secretions. The diarrhea can be massive—more than a quart of stool an hour in cholera. Other substances that cause salt and water secretion include certain laxatives, such as castor oil, and bile acids (which may build up after surgery to remove part of the small intestine). Certain rare tumors—such as carcinoid, gastrinoma, and vipoma—also can cause secretory diarrhea, as can some polyps.

Inflammatory diarrhea occurs when the lining of the large intestine becomes inflamed, ulcerated, or engorged and releases proteins, blood, mucus, and other fluids, which increase the bulk and fluid content of the stool. This type of diarrhea can be caused by many diseases, including ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease (regional enteritis), tuberculosis, and cancers such as lymphoma and adenocarcinoma. When the lining of the rectum is affected, people often feel an urgent need to move their bowels and have frequent bowel movements because the inflamed rectum is more sensitive to expansion (distention) by stool.

DRUGS USED TO TREAT DIARRHEA

DRUGS USED TO TREAT DIARRHEA

| DRUG | SOME SIDE EFFECTS | COMMENTS |

| Adsorbents | ||

| Bismuth subsalicylate Kaolin Pectin |

Well tolerated | Adsorbents are less potent than intestinal muscle relaxants. |

| Intestinal muscle relaxants | ||

| Codeine Diphenoxylate Loperamide* Paregoric (tincture of opium) |

Obstruction of the large intestine | Doctors use these drugs carefully if they suspect infectious cause of diarrhea. |

| * Some formulations of loperamide are available over-the-counter. | ||

Evaluation

The evaluation depends on whether the diarrhea is acute (sudden and present for a short time) or chronic (persistent).

For acute diarrhea that lasts for more than 72 hours (or sooner if blood is present, or the person is weak or has a fever, rash, or severe pain), a doctor should be consulted. If, on the doctor’s examination, the person does not appear to be dehydrated or seriously ill, and the diarrhea is not severe and has lasted for less than a week, testing is usually not needed. Other people may need blood tests for electrolyte abnormalities or stool tests for blood, white blood cells, and the presence of infectious organisms (for example, bacteria such as Campylobacter and Yersinia and parasites such as amebas, Giardia, and Cryptosporidium). Some causes of infection are detected by looking under the microscope, whereas others require a culture (growing the organism in the laboratory) or special enzyme tests (for example, Shigella or Giardia). If the person has taken antibiotics recently, the doctor may test the stool for Clostridium difficile toxin. A colonoscopy is usually not necessary.

For chronic diarrhea, similar tests are performed. In addition, the doctor may test the stool for fat (indicating malabsorption) and perform a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy to examine the lining of the rectum and colon. Sometimes a biopsy (removal of a tissue specimen for examination under a microscope) of the rectal lining is performed. Sometimes the volume of stool over a 24-hour period is determined. Secret (surreptitious) use of a laxative also can be identified in the stool sample.

Treatment

Diarrhea is a symptom, and its treatment depends on its cause. For most people, treating diarrhea involves only removing the cause to suppress the diarrhea until the body heals itself. A viral cause usually resolves by itself in 24 to 48 hours. Extra fluids containing a balance of water, sugars, and salts are needed for people who are dehydrated. As long as the person is not vomiting excessively, these fluids can be given by mouth (see box on page 1733). Seriously ill people and those with significant electrolyte abnormalities require intravenous fluid and sometimes hospitalization.

Many prescription and over-the-counter drugs are available for the treatment of diarrhea. Over-the-counter drugs include adsorbents (for example, kaolin-pectin), which adhere to chemicals, toxins, and infectious organisms. Some adsorbents also help firm up the stool. Bismuth helps many people with diarrhea. It has a normal side effect of turning the stool black. Other drugs used are loperamide, codeine, and diphenoxylate.

Prescription drugs used to treat diarrhea include opioids and other drugs that relax the muscles of the intestines. Bulking agents used for chronic constipation, such as psyllium or methylcellulose, can sometimes help relieve chronic diarrhea as well.

DIFFICULTY SWALLOWING

Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) is the sensation that food is not moving normally through the esophagus (the tube that connects the throat to the stomach) or that the food has become stuck on the way down.

Causes

A swallowing difficulty can result from a physical blockage or a problem with the nerves or muscles of the esophagus (esophageal motility [movement] disorder). Sometimes, a swallowing difficulty may be imagined (psychogenic).

Mechanical blockage can result from cancer of the esophagus, rings or webs of tissue across the inside of the esophagus, and scarring of the esophagus from chronic acid reflux or from swallowing caustic solutions. Sometimes the esophagus is compressed by an enlarged thyroid, a bulge in the large artery in the chest (aortic aneurysm), or a tumor in the chest, such as one caused by lung cancer.

Esophageal motility disorders include achalasia (in which the rhythmic contractions of the esophagus are greatly decreased and the lower esophageal muscle does not relax normally) and esophageal spasm. Systemic sclerosis may also cause a motility disorder.

Evaluation and Treatment

Equal difficulty swallowing liquids and solids suggests a motility disorder. Gradually increasing difficulty swallowing first solids and then liquids suggests a worsening physical obstruction, such as a tumor. Doctors usually take x-rays while the person swallows a marshmallow or tablet along with barium liquid (which shows up on x-rays). Or they look in the esophagus and stomach with a flexible tube (upper endoscopy).

The specific cause is treated. To relieve symptoms, doctors usually advise the person to take small bites and chew food thoroughly.

DYSPEPSIA

Dyspepsia is pain or discomfort in the middle of the upper abdomen.

The sensation may be described as indigestion, gassiness, a sense of fullness, or a gnawing or burning pain. Other symptoms may include a poor appetite, nausea, constipation, diarrhea, flatulence, belching, and loud intestinal sounds (borborygmi). For some people, eating makes symptoms worse; for others, eating relieves symptoms.

Causes

Dyspepsia has many causes, including stomach ulcers, duodenal ulcers, and stomach cancer. Stomach inflammation (gastritis) may also cause dyspepsia. Helicobacter pylori bacteria may contribute to dyspepsia by causing inflammation and ulcers of the stomach and duodenum (the first segment of the small intestine). Gallstones, when present in the tubes (ducts) that drain bile from the gallbladder, sometimes produce dyspepsia. Some drugs, especially aspirin and other NSAIDs, cause symptoms. In many people, however, no abnormality can be found (a condition called functional dyspepsia), and symptoms are linked to increased sensitivity in the stomach or increased contractions (spasms).

Anxiety can cause or worsen dyspepsia—possibly because anxiety can increase a person’s perception of unpleasant sensations, so that minor discomfort becomes very distressing. Sometimes, anxiety may worsen the abnormal stomach sensitivity and contractions or cause a person to sigh or gasp and swallow air (aerophagia).

Evaluation and Treatment

Symptoms that suggest a more serious cause of dyspepsia include prolonged loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, weight loss, anemia, blood in the stools, and difficulty or pain with swallowing. For people with these symptoms and those over age 45, doctors typically look in the esophagus and stomach with a flexible tube (upper endoscopy). Those who are younger and have no symptoms other than dyspepsia are often given a course of treatment with acid-blocking drugs. If this treatment is unsuccessful, doctors usually perform endoscopy.

FECAL INCONTINENCE

Fecal incontinence is the loss of control over bowel movements.

Causes

Fecal incontinence can occur briefly during bouts of diarrhea or when hard stool becomes lodged in the rectum (fecal impaction). Persistent fecal incontinence can develop in people who have injuries to the anus or spinal cord, rectal prolapse (protrusion of the rectal lining through the anus), dementia, neurologic injury from diabetes, tumors of the anus, or injuries to the pelvis during childbirth.

Evaluation

A doctor examines the person for any structural or neurologic abnormality. This involves examining the anus and rectum, checking the extent of sensation around the anus, and usually performing a sigmoidoscopy. Other tests, including an ultrasound of the anal sphincter, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and an examination of the function of nerves and muscles lining the pelvis, may be needed.

Treatment

The first step in correcting fecal incontinence is to try to establish a regular pattern of bowel movements that produces well-formed stool. Dietary changes, including the addition of a small amount of fiber, often help. If such changes do not help, a drug that slows bowel movements, such as loperamide, may be successful.

Exercising the anal muscles (sphincters) by squeezing and releasing them increases their tone and strength. Using a technique called biofeedback, a person can retrain the sphincters and increase the sensitivity of the rectum to the presence of stool. About 70% of well-motivated people benefit from biofeedback.

If fecal incontinence persists, surgery may help—for instance, when the cause is an injury to the anus or an anatomic defect in the anus. As a last resort, a colostomy (the surgical creation of an opening between the large intestine and the abdominal wall—see art on page 194) may be performed. The anus is sewn shut, and stool is diverted into a removable plastic bag attached to the opening in the abdominal wall.

GAS-RELATED COMPLAINTS

Gas is normally present in the digestive system and may be expelled through the mouth (belching) or through the anus (flatus).

There are three main gas-related complaints: excessive belching, the sensation of abdominal distention or bloating, and excessive flatus (known colloquially as farting).

Belching is more likely to occur shortly after eating or during periods of stress. Some people feel a tightness in their chest or stomach just before belching that is relieved as the gas is expelled.

People normally pass gas through the anus more than 10 times a day, but some people pass gas more often. Gas passed through the anus may or may not have an odor. On occasion, fecal incontinence occurs as a person tries to pass gas, only to be surprised by the expulsion of stool as well.

Causes

Increased amounts of gas can gather in the stomach or farther along the digestive tract.

Belching results from swallowed air or from gas generated by carbonated beverages. Swallowing small amounts of air is normal, but some people unconsciously swallow large amounts (aerophagia) while eating or smoking and also at other times, especially when they feel anxious. Excessive salivation, which may occur with gastroesophageal reflux, ill-fitting dentures, and gum chewing, increases air swallowing. Most swallowed air is later belched up, and very little passes from the stomach into the rest of the digestive system. Most of the swallowed air that makes it into the intestines is absorbed through the walls of the intestines into the bloodstream, and very little is passed through the anus.

Flatus results from hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide gases that are produced by bacterial breakdown of food in the intestine, especially after a person eats certain foods such as beans and cabbage. Almost anyone who eats large amounts of proteins or fruits will develop some degree of flatulence. People who have deficiencies of the enzymes that break down certain sugars (such as those with lactase deficiency) also tend to produce large amounts of gas when they eat foods containing these sugars. Other malabsorption syndromes, such as tropical sprue and pancreatic insufficiency, also may lead to the production of large amounts of gas.

A bloating sensation can be present in people who have digestive disorders such as poor stomach emptying (gastroparesis) or irritable bowel syndrome. Sometimes, the only symptom in heart disease is a feeling of bloating. However, aside from those who drink carbonated beverages or swallow excessive air, most people who have a sensation of bloating do not seem to have excessive gas in their digestive system. Some people, such as those who have irritable bowel syndrome, are particularly sensitive to normal amounts of gas.

Evaluation and Treatment

Doctors do not usually perform any testing on people who belch. Those who have flatus may require tests if their symptoms suggest a malabsorption syndrome.

Bloating and belching are difficult to relieve. If belching is the main problem, reducing the amount of air being swallowed can help, which is difficult because people usually are not aware of swallowing air. Avoiding chewing gum and eating more slowly in a relaxed atmosphere may help. Avoiding carbonated beverages helps some people.

People who pass flatus excessively may need to change their diet by avoiding foods that are difficult to digest. Discovering which foods cause a problem may require eliminating one food or group of foods at a time. A person can start by eliminating foods containing hard-to-digest carbohydrates (such as beans and cabbage), milk and dairy products, then fresh fruits, and then certain vegetables and other foods.

Simethicone, which is present in some antacids and is also available by itself, may provide some minor relief. Sometimes other drugs—including other types of antacids (including those that contain baking soda), metoclopramide, and bethanechol—may help. Aromatic oils, such as peppermint oil, help some people, especially those who experience cramps with flatulence. Eating more fiber helps some people but worsens the symptoms in others. Chlorophyll, an ingredient in many over-the-counter products, and charcoal tablets do not decrease flatulence but help reduce its offensive odor.

GLOBUS SENSATION

Globus sensation (previously called globus hystericus) is the feeling of having a lump in the throat when there is no lump.

The feeling produced by globus sensation is similar to that experienced when feeling emotionally choked up, such as during events that trigger grief, anxiety, anger, pride, or happiness. Food does not stick in the throat, and the person is able to swallow liquids without difficulty. Eating and drinking may actually provide relief.

Globus sensation may result from abnormal muscle activity or sensitivity of the esophagus. It sometimes occurs when stomach acid and enzymes flow backward from the stomach into the esophagus (gastroesophageal reflux). Globus sensation also may occur with frequent swallowing and drying of the throat caused by anxiety or another strong emotion or by rapid breathing.

Doctors do not usually perform tests as long as the person is able to swallow normally and has no other symptoms such as pain, weight loss, or blood in the stool.

LOSS OF APPETITE

Loss of appetite (anorexia) implies that hunger is absent—a person with anorexia has no desire to eat. In contrast, a person with an eating disorder such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa (see page 876) is hungry but restricts food intake or vomits after eating because of overconcern about weight gain.

A brief period of anorexia usually accompanies almost all sudden (acute) illnesses. Long-lasting (chronic) anorexia usually occurs only in people with a serious underlying disorder such as cancer; AIDS; chronic lung disease; and severe heart, kidney, or liver failure. Disorders that affect the part of the brain where appetite is regulated can cause anorexia as well. Anorexia is common in people who are dying. Some drugs, such as digoxin, fluoxetine, quinidine, and hydralazine, cause anorexia.

Most often, anorexia occurs in a person with a known underlying disorder. Unexplained chronic anorexia is a signal to the doctor that something is wrong. A thorough evaluation of the person’s symptoms and a complete physical examination often suggest a cause and help the doctor decide which tests are needed.

Underlying causes are treated to the extent possible. Steps that can help increase a person’s desire to eat include providing favorite foods, a flexible meal schedule, and, if the person desires, a small amount of an alcoholic beverage served 30 minutes before meals. In certain situations, doctors may use drugs, such as cyproheptadine, low-dose corticosteroids, megestrol, and dronabinol, to help stimulate the appetite.

NAUSEA AND VOMITING

Nausea is an unpleasant feeling that may include dizziness, vague discomfort in the abdomen, an unwillingness to eat, and a sensation of needing to vomit. Vomiting is the forceful contraction of the stomach that propels its contents up the esophagus and out through the mouth. Vomiting serves to empty the stomach of its contents and often makes a person with nausea feel considerably better, at least temporarily. Vomiting is not the same as regurgitation, which is the spitting up of stomach contents without forceful abdominal contractions and nausea.

Vomitus—the material that is vomited up—usually reflects what was recently eaten. Sometimes it contains chunks of food. When blood is vomited, the vomitus is usually bright red (hematemesis). When bile is present, the vomitus is green.

Even normal vomiting can be violent. A person who is vomiting typically doubles over and makes considerable noise. Severe vomiting can project food many feet (projectile vomiting). Vomiting greatly increases pressure within the esophagus, and severe vomiting can tear or even rupture the lining of the esophagus. People who are unconscious can inhale their vomitus. The acidic nature of the vomitus can severely irritate the lungs. Frequent vomiting can cause dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities; newborns and infants are particularly susceptible to these complications.

Causes

Nausea and vomiting result when the vomiting center in the brain is activated. These symptoms commonly occur with any dysfunction of the digestive tract but are particularly common with gastroenteritis and bowel obstruction. Obstruction of the intestine causes vomiting because food and fluids back up into the stomach from the blockage. The vomiting center also can be activated by certain brain disorders, including infections (such as meningitis and encephalitis), brain tumors, and migraines.

The balance organs of the inner ear (vestibular apparatus) are connected to the vomiting center. This connection is why some people become nauseated by the movement of a boat, car, or airplane and by certain disorders of the inner ear (such as labyrinthitis and positional vertigo). Nausea and vomiting may also occur during pregnancy, particularly during the early weeks and especially in the morning. Many drugs, including opioid analgesics, such as morphine, and chemotherapy drugs, can cause nausea.

Psychologic problems also can cause nausea and vomiting (known as functional, or psychogenic, vomiting). Such vomiting may be intentional—for instance, a person who has bulimia vomits to lose weight. Or it may be unintentional—a conditioned response to address psychologic distress, such as to avoid going to school.

Evaluation

Otherwise healthy adults and older children who have only a few episodes of vomiting (with or without diarrhea) and no other symptoms may not require evaluation. Young children and older people, and those in whom vomiting lasts more than 1 day or who have any other symptoms, particularly abdominal pain, headache, weakness, or confusion, are evaluated by the doctor. If the person’s symptoms and physical examination show no signs of dehydration or serious underlying illness, doctors may not perform any testing. Women of childbearing age may receive a pregnancy test. In others, blood tests may be obtained to look for signs of dehydration or abnormal electrolyte levels. If bowel obstruction is suspected, x-rays are obtained.

Treatment

Specific conditions are treated. If there is no serious underlying disorder and the person is not dehydrated, small amounts of clear liquids may be given an hour or so after the last bout of vomiting. If these liquids are tolerated, the amounts are increased gradually. When these increases are tolerated, the person may resume eating normal foods. If the person is dehydrated and can tolerate some liquids by mouth, doctors usually recommend oral rehydration solutions. Those with significant dehydration or electrolyte abnormalities and those who cannot tolerate liquids by mouth usually require intravenous fluids.

For some adults and adolescents, doctors use anti-nausea drugs such as metoclopramide or prochlorperazine. For people whose vomiting is caused by chemotherapy, doctors usually use stronger drugs such as odansetron or granisetron.

REGURGITATION

Regurgitation is the spitting up of food from the esophagus or stomach without nausea or forceful contractions of the abdominal muscles.

A ring-shaped muscle (sphincter) between the stomach and esophagus normally helps prevent regurgitation. Regurgitation of sour or bitter-tasting material can result from acid coming up from the stomach. Regurgitation of tasteless fluid containing mucus or undigested food can result from a narrowing (stricture) or a blockage of the esophagus. The blockage may result from acid damage to the esophagus, ingestion of caustic substances, cancer of the esophagus, or abnormal nerve control that interferes with coordination between the esophagus and its sphincter at the opening to the stomach.

Regurgitation sometimes occurs with no apparent physical cause. Such regurgitation is called rumination. In rumination, small amounts of food are regurgitated from the stomach, usually 15 to 30 minutes after eating. The material often passes all the way to the mouth where a person may chew it again and reswallow it. Rumination occurs without pain or difficulty in swallowing. Rumination is common in infants. In adults, rumination most often occurs among people who have emotional disorders, especially during periods of stress.

Diagnosis

Usually, a doctor can determine whether a person has a digestive disorder based on a medical history and a physical examination. The doctor can then select appropriate procedures that help to confirm the diagnosis, determine the extent and severity of the disorder, and aid in planning treatment.

MEDICAL HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A doctor identifies symptoms by interviewing a person to obtain the medical history. Doctors ask specific questions to gain additional information. For example, in speaking with a person who has abdominal pain, the doctor might first ask, “What is the pain like?” This question might be followed by questions such as, “Does the pain get better after you eat?” or “Does the pain get worse when you bend over?”

During the physical examination, the doctor notes the person’s weight and overall appearance, which may be indicators of digestive disorders. Although the doctor may examine the entire body, emphasis is placed on examining the abdomen, anus, and rectum.

First, the doctor observes the abdomen from different angles, looking for expansion (distention) of the abdominal wall that might accompany abnormal growth or enlargement of an organ. A stethoscope is placed on the abdomen, through which the doctor listens for sounds that normally accompany the movement of material through the intestines and for any abnormal sounds. The doctor feels for tenderness and any abnormal masses or enlarged organs. Pain that is caused by gentle pressure on the abdomen and that is relieved when the pressure is released (rebound tenderness) usually indicates inflammation and sometimes infection of the lining of the abdominal cavity (peritonitis).

The anus and rectum are examined with a gloved finger, and a small sample of stool is sometimes tested for hidden (occult) blood. In women, a pelvic examination often helps distinguish digestive problems from gynecologic ones.

PSYCHOLOGIC EVALUATION

Because the digestive system and the brain are highly interactive, a psychologic evaluation is sometimes needed in the evaluation of digestive problems. In such cases, doctors are not implying that the digestive problems are made up or imagined. Rather, the digestive problems may be the result of anxiety, depression, or other treatable mental disorders, which seems to be true for as many as 50% of people with symptoms of a digestive disorder.

DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES

Based on the findings of the medical history, physical examination, and, if applicable, psychologic evaluation, doctors choose appropriate tests. Tests performed on the digestive system make use of endoscopes (flexible tubes that doctors use to view internal structures and to obtain tissue samples from inside the body), x-rays, ultrasound scans, tiny amounts of radioactive materials, capsule endoscopy, and chemical measurements. These tests can help a doctor locate, diagnose, and sometimes treat a problem. Some tests require the digestive system to be cleared of stool, some require 8 to 12 hours of fasting, and others require no preparation.

Although diagnostic tests can be very accurate, they can also be quite expensive and, in rare cases, can cause bleeding or injury.

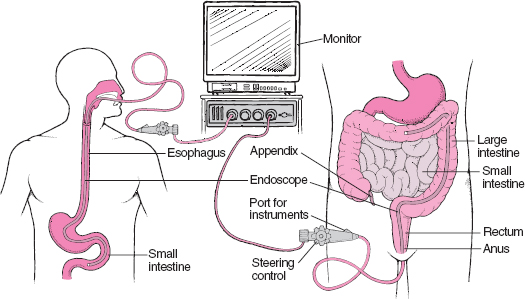

Endoscopy

Endoscopy is an examination of internal structures using a flexible viewing tube (endoscope). When passed through the mouth, an endoscope can be used to examine the esophagus (esophagoscopy), the stomach (gastroscopy), and part of the small intestine (upper gastrointestinal endoscopy). When passed through the anus, an endoscope can be used to examine the rectum (anoscopy); the lower portion of the large intestine, the rectum, and the anus (sigmoidoscopy); and the entire large intestine, the rectum, and the anus (colonoscopy). For procedures other than anoscopy and sigmoidoscopy, the person is given drugs intravenously to prevent discomfort.

Endoscopes range in diameter from about 1/4 inch (a bit more than 1/2 centimeter) to about 1/2 inch (1 1/4 centimeters) and range in length from about 1 foot (about 30 1/2 centimeters) to about 6 feet (almost 2 meters). The choice of endoscope depends on which part of the digestive tract is to be examined. The endoscope is flexible and provides both a lighting source and a small camera, which allows doctors to get a good view of the tract lining. The doctor can see areas of irritation, ulcers, inflammation, and abnormal tissue growth.

Viewing the Digestive Tract With an Endoscope

A flexible tube called an endoscope is used to view different parts of the digestive tract. The tube contains several channels along its length. The different channels are used to transmit light to the area being examined, to view the area through a camera lens (with a camera at the tip of the tube), to pump fluids or air in or out, and to pass biopsy or surgical instruments through.

When passed through the mouth, an endoscope can be used to examine the esophagus, the stomach, and some of the small intestine. When passed through the anus, an endoscope can be used to examine the rectum and the entire large intestine. The instrument used in the different procedures varies in length and size of the tube.

Many endoscopes are equipped with a small clipper with which tissue samples can be taken (endoscopic biopsy). These samples can then be evaluated for inflammation, infection, or cancer. Because the lining and the inner layers of the walls of the digestive tract do not have nerves that sense pain (with the exception of the lower part of the anus), this procedure is painless.

Endoscopes can also be used for treatment. A doctor can pass different types of instruments through a small channel in the endoscope. An electric probe at the tip of the endoscope can be used to destroy abnormal tissue, to remove small growths, or to close off a blood vessel. A needle at the tip can be used to inject drugs into dilated veins in the esophagus and stop their bleeding. A laser mounted at the end can be used to destroy abnormal tissue.

Before having an endoscope passed through the mouth, a person usually must avoid food for several hours. Food in the stomach can obstruct the doctor’s view and might be vomited up during the procedure. Before having an endoscope passed into the rectum and colon, a person usually takes laxatives and is sometimes given enemas to clear out any stool. In addition, the person must avoid food for several hours because it might be vomited up and because it would reduce the effectiveness of the laxatives and enemas.

Complications from endoscopy are relatively rare. Although endoscopes can injure or even perforate the digestive tract, they more commonly cause irritation of the tract lining and a little bleeding.

Capsule Endoscopy

Capsule endoscopy is a procedure in which the person swallows a battery-powered capsule. The capsule contains one or two small cameras, a light, and a transmitter. Images of the lining of the intestines are transmitted to a receiver worn on the person’s belt or in a cloth pouch. Thousands of pictures are taken. This technology is especially good at finding problems on the inner surface of the small intestine, which is an area that is difficult to evaluate with an endoscope.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is an examination of the abdominal cavity using an endoscope, usually with the person under general anesthesia. After the appropriate area of the skin is washed with an antiseptic, a small incision is made, usually in the navel. Then an endoscope is passed into the abdominal cavity. A doctor can look for tumors or other abnormalities, examine virtually any organ in the abdominal cavity, obtain tissue samples, and even do surgery. Complications include bleeding, infection, and perforation.

X-ray Studies

X-rays often are used to evaluate digestive problems. Standard x-rays do not require any special preparation (see page 2042). These x-rays usually can show an obstruction or paralysis of the digestive tract or abnormal air patterns in the abdominal cavity. Standard x-rays can also show enlargement of the liver, kidneys, and spleen.

Barium studies often provide more information. X-rays are taken after a person swallows barium in a flavored liquid mixture or as barium-coated food. The barium looks white on x-rays and outlines the digestive tract, showing the contours and lining of the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. Barium collects in abnormal areas, showing ulcers, tumors, obstructions, erosions, and enlarged, dilated esophageal veins.

X-rays may be taken at intervals to determine where the barium is. In a continuous x-ray technique called fluoroscopy, the barium is observed as it moves through the digestive tract. With this technique, doctors can see how the esophagus and stomach function, determine whether their contractions are normal, and tell whether food is getting blocked. The doctor may film this process for later review.

Barium also can be given in an enema to outline the lower part of the large intestine. Then, x-rays can show polyps, tumors, or other structural abnormalities. This procedure may cause crampy pain, producing slight to moderate discomfort.

Barium taken by mouth or as an enema is eventually excreted in the stool, making the stool chalky white. Because barium can cause significant constipation, the doctor may give a gentle laxative to speed up the elimination of barium.

Ultrasound Scanning

Ultrasound scanning uses sound waves to produce pictures of internal organs (see page 2044). An ultrasound scan can show the size and shape of many organs, such as the liver and pancreas, and can also show abnormal areas within them, such as cysts and some tumors. It can also show fluid in the abdominal cavity (ascites). Ultrasound scanning with a probe on the abdominal wall is not a good method for examining the lining of the digestive tract. Endoscopic ultrasound, however, shows the lining more clearly because the probe is placed on the tip of an endoscope.

An ultrasound scan is painless and poses no risk of complications. Endoscopic ultrasound poses the same risk of complications as endoscopy.

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Computed tomography (CT—see page 2037) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI—see page 2040) scans are good tools for assessing the size and location of abdominal organs. Additionally, growths such as cancerous (malignant) or noncancerous (benign) tumors are often detected by these tests. Changes in blood vessels can be detected as well. Inflammation, such as that of the appendix (appendicitis) or diverticula (diverticulitis), is usually evident. Sometimes, these tests are used to help guide radiologic or surgical procedures.

Paracentesis

Paracentesis is the insertion of a needle into the abdominal cavity for the removal of fluid. Normally, the abdominal cavity contains only a small amount of fluid. However, fluid can accumulate in certain circumstances, such as when a person has liver disease, heart failure, a ruptured stomach or intestine, cancer, or a ruptured spleen. A doctor may use paracentesis to aid in diagnosis (for example, to obtain a fluid sample for analysis) or as part of treatment (for example, to remove excess fluid).

Before paracentesis, a physical examination, sometimes accompanied by an ultrasound scan, is performed to confirm that the abdominal cavity contains excess fluid. Next, an area of the skin, usually just below the navel, is washed with an antiseptic solution and numbed with a small amount of anesthetic. A doctor then pushes a needle attached to a syringe through the skin and muscles of the abdominal wall and into the area of fluid accumulation. A small amount of fluid may be removed for laboratory testing, or up to several quarts may be removed to relieve distention. Complications include perforation of the digestive tract and bleeding.

Occult Blood Tests

Bleeding in the digestive system can be caused by something as insignificant as a little irritation or as serious as cancer. Amounts of blood too small to be seen or to change the appearance of stool can be detected chemically. The detection of such small amounts may provide early clues to the presence of ulcers, cancers, and other abnormalities.

During a rectal examination, the doctor may obtain a small amount of stool on a gloved finger. This sample is placed on a piece of filter paper impregnated with a chemical (guaiac). After another chemical is added, the sample will change color if blood is present. More preferably, the person can take home a kit containing the filter papers. The person places samples of stool from about three different bowel movements on the filter papers, which are then mailed in special containers back to the doctor for testing. If blood is detected, further examinations are needed to determine the source.

Intubation of the Digestive Tract

Intubation of the digestive tract is the process of passing a small, flexible plastic tube (nasogastric tube) through the nose or mouth into the stomach or small intestine. This procedure may be used for diagnostic or treatment purposes. Intubation typically causes gagging and nausea, so a numbing spray is usually applied into the nose and back of the throat. The tube size varies according to the purpose.

Nasogastric intubation can be used to obtain a sample of stomach fluid. The tube is passed through the nose rather than through the mouth, primarily because the tube can be more easily guided to the esophagus. Also, passage of a tube through the nose is less irritating and less likely to trigger coughing. Doctors can determine whether the stomach contains blood, or they can analyze the stomach’s secretions for acidity, enzymes, and other characteristics. In people with poisoning, samples of the stomach fluid can be analyzed to identify the poison. In some cases, the tube is left in place so that samples can be obtained over several hours.

Nasogastric intubation may also be used to treat certain conditions. For example, poisons can be pumped out or neutralized with activated charcoal, or liquid food can be given to people who cannot swallow.

Sometimes nasogastric intubation is used to continuously remove the contents of the stomach. The end of the tube is usually attached to a suction device, which removes gas and fluid from the stomach. This helps relieve pressure when the digestive system is blocked or otherwise not functioning properly. This type of tube is often used after abdominal surgery until the digestive system can resume its normal function.

In a procedure called 24-hour pH testing, a tube is placed through the nose into the esophagus, where it sits for 24 hours. The tube frequently samples the fluid of the esophagus, allowing detection of stomach acid that comes up into the chest (esophageal reflux). This test allows the doctors to measure the severity and frequency of reflux.

In nasoenteric intubation, a longer tube is passed through the nose, through the stomach, and into the small intestine. This procedure can be used to remove a sample of intestinal contents, continuously remove fluids, or provide food.

Manometry

Manometry is a test in which a tube with pressure gauges along its surface is placed in the esophagus. Using this device (manometer), a doctor can determine whether contractions of the esophagus can propel food normally. Sometimes a doctor uses a similar device to measure pressure in the anal sphincter to determine whether the muscle opens normally.