CHAPTER 23

Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis is inflammation of the pancreas.

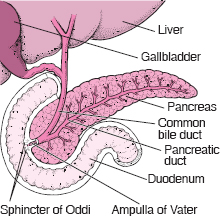

The pancreas is a leaf-shaped organ about 5 inches (about 13 centimeters) long. It is surrounded by the lower edge of the stomach and the wall of the duodenum (the first portion of the small intestine leading out of the stomach). The pancreas has three major functions:

To secrete fluid containing digestive enzymes into the duodenum

To secrete fluid containing digestive enzymes into the duodenum

To secrete the hormones insulin and glucagon, which help regulate sugar levels in the bloodstream

To secrete the hormones insulin and glucagon, which help regulate sugar levels in the bloodstream

To secrete into the duodenum the large quantities of sodium bicarbonate (the chemical in baking soda) needed to neutralize the acid coming from the stomach

To secrete into the duodenum the large quantities of sodium bicarbonate (the chemical in baking soda) needed to neutralize the acid coming from the stomach

Inflammation of the pancreas can be caused by gallstones, alcohol, various drugs, some viral infections, and digestive enzymes. Pancreatitis usually develops quickly and subsides within a few days but can last for a few months (acute pancreatitis). In some cases, however, inflammation persists and gradually destroys pancreatic function (chronic pancreatitis).

Acute Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis is sudden inflammation of the pancreas that may be mild or life threatening but usually subsides.

Gallstones and alcohol abuse are the main causes of acute pancreatitis.

Gallstones and alcohol abuse are the main causes of acute pancreatitis.

Severe abdominal pain is the predominant symptom.

Severe abdominal pain is the predominant symptom.

Blood tests and imaging tests, such as x-rays and computed tomography, help the doctor make the diagnosis.

Blood tests and imaging tests, such as x-rays and computed tomography, help the doctor make the diagnosis.

Whether mild or severe, acute pancreatitis usually requires hospitalization.

Whether mild or severe, acute pancreatitis usually requires hospitalization.

Gallstones (biliary tract disease—see page 243) and alcohol abuse account for almost 80% of hospital admissions for acute pancreatitis. About 1 1/2 times as many women as men have acute pancreatitis caused by gallstones. Normally, the pancreas secretes pancreatic fluid through the pancreatic duct to the duodenum. This pancreatic fluid contains digestive enzymes in an inactive form and inhibitors that inactivate any enzymes that become activated on the way to the duodenum. Blockage of the pancreatic duct by a gallstone stuck in the sphincter of Oddi stops the flow of pancreatic fluid. Usually, the blockage is temporary and causes limited damage, which is soon repaired. But if the blockage remains, activated enzymes accumulate in the pancreas, overwhelm the inhibitors, and begin to digest the cells of the pancreas, causing severe inflammation.

Drinking as little as 2 ounces of alcohol a day (half a bottle of wine, 4 bottles of beer, or 5 ounces of liquor) for several years may cause the small ductules in the pancreas that drain into the pancreatic duct to clog, eventually causing acute pancreatitis. An attack of pancreatitis may be precipitated by an alcoholic binge or by an excessively large meal. Many other conditions can also cause acute pancreatitis.

Many drugs can irritate the pancreas. Usually, the inflammation resolves when the drugs are stopped. Viruses can cause pancreatitis, which is usually short-lived.

Symptoms

Almost everyone with acute pancreatitis suffers severe abdominal pain in the upper abdomen, below the breastbone (sternum). The pain often penetrates to the back in about 50% of people. Rarely, the pain is first felt in the lower abdomen. When acute pancreatitis is caused by gallstones, the pain usually starts suddenly and reaches its maximum intensity in minutes. When pancreatitis is caused by alcoholism, pain develops over a few days. The pain then

Locating the Pancreas

Some Causes of Acute Pancreatitis

Gallstones

Gallstones

Alcohol abuse

Alcohol abuse

Drugs such as furosemide and azathioprine

Drugs such as furosemide and azathioprine

Estrogen use in women with high levels of lipids in the blood

Estrogen use in women with high levels of lipids in the blood

Hyperparathyroidism and high levels of calcium in the blood

Hyperparathyroidism and high levels of calcium in the blood

Mumps

Mumps

High levels of lipids (especially triglycerides) in the blood

High levels of lipids (especially triglycerides) in the blood

Damage to the pancreas from surgery or endoscopy

Damage to the pancreas from surgery or endoscopy

Damage to the pancreas from blunt or penetrating injuries

Damage to the pancreas from blunt or penetrating injuries

Cancer of the pancreas

Cancer of the pancreas

Reduced blood supply to the pancreas, for example, from severely low blood pressure

Reduced blood supply to the pancreas, for example, from severely low blood pressure

Hereditary pancreatitis

Hereditary pancreatitis

Kidney transplantation

Kidney transplantation

remains steady and severe, has a penetrating quality, and persists for days.

Coughing, vigorous movement, and deep breathing may worsen the pain. Sitting upright and leaning forward may provide some relief. Most people feel nauseated and have to vomit, sometimes to the point of dry heaves (retching without producing any vomit). Often, even large doses of an injected opioid analgesic (see page 642) do not relieve pain completely.

Some people, especially those who develop acute pancreatitis because of alcohol abuse, may never develop any symptoms other than moderate pain. Others feel terrible. They look sick and sweaty and have a fast pulse (100 to 140 beats a minute) and shallow, rapid breathing. Rapid breathing may occur if people have inflammation of the lungs, areas of collapsed lung tissue (atelectasis—see page 495), or accumulation of fluid in the chest cavity (pleural effusion—see page 518). These conditions decrease the amount of lung tissue available to transfer oxygen from the air to the blood.

At first, body temperature may be normal, but it increases in a few hours to between 100° F and 101° F (37.7° C and 38.3° C). Blood pressure may be high or low, but it tends to fall when the person stands, causing faintness. As acute pancreatitis progresses, people tend to be less and less aware of their surroundings—some are nearly unconscious. Occasionally, the whites of the eyes (sclera) become yellowish.

Complications: Damage to the pancreas may permit activated enzymes and toxins such as cytokines (see page 1101) to enter the bloodstream and cause low blood pressure and damage to organs outside of the abdominal cavity, such as the lungs and kidneys. The part of the pancreas that produces hormones, especially insulin, tends not to be damaged or affected. One of five people with acute pancreatitis develops some swelling in the upper abdomen. This swelling may occur because the movement of stomach and intestinal contents stops (a condition called ileus—see page 204).

In severe acute pancreatitis, parts of the pancreas die (necrotizing pancreatitis), and blood and pancreatic fluid may escape into the abdominal cavity, which decreases blood volume and results in a large drop in blood pressure, possibly causing shock (see page 350). Severe acute pancreatitis can be life threatening.

Infection of an inflamed pancreas is a risk, particularly after the first week of illness. Sometimes, a doctor suspects an infection because the person’s condition worsens and because a fever and high white blood cell count develop after other symptoms had initially started to subside. The diagnosis is made by culturing blood samples (growing large numbers of bacteria) to identify bacteria that are causing the infection and performing a computed tomography (CT) scan. A doctor may be able to withdraw a sample of infected material from the pancreas by inserting a needle through the skin and into the pancreas. An infection is treated with antibiotics, and surgical removal of infected and dead tissue usually is necessary.

Sometimes, a collection of pancreatic enzymes, fluid, and tissue debris resembling a cyst (a pseudocyst) forms in the pancreas and expands like a balloon. If a pseudocyst grows larger and causes pain or other symptoms, a doctor drains it quickly because death can result if the pseudocyst expands further, becomes infected, bleeds, or ruptures. Depending on its location, the pseudocyst is drained either by performing a surgical procedure or by inserting a catheter through the skin or through an endoscope (a flexible viewing tube) that is passed through the mouth and into the stomach or intestine and allowing the pseudocyst to drain for several weeks.

Diagnosis

Characteristic abdominal pain leads a doctor to suspect acute pancreatitis, especially in a person who has gallbladder disease or who is an alcoholic. On examination, a doctor often notes that the abdominal wall muscles are rigid. When listening to the abdomen with a stethoscope, a doctor may hear few or no bowel (intestinal) sounds.

No single blood test proves the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, but certain tests corroborate it. Blood levels of two enzymes produced by the pancreas, amylase and lipase, usually increase on the first day of the illness but return to normal in 3 to 7 days. If the person has had other flare-ups (bouts or attacks) of pancreatitis, however, the levels of these enzymes may not increase, because so much of the pancreas may have been destroyed that few cells are left to release the enzymes. The white blood cell count is usually increased.

X-rays of the abdomen may show dilated loops of intestine or, rarely, one or more gallstones. Chest x-rays may reveal areas of collapsed lung tissue or an accumulation of fluid in the chest cavity. An ultrasound may show gallstones in the gallbladder or sometimes in the common bile duct and also may detect swelling of the pancreas.

A CT scan is particularly useful in detecting inflammation of the pancreas and is used in people with severe acute pancreatitis and in people with complications, such as extremely low blood pressure. Because the images are so clear, a CT scan helps a doctor make a precise diagnosis.

Prognosis

In severe acute pancreatitis, a CT scan helps determine the outlook, or prognosis. If the scan indicates that the pancreas is only mildly swollen, the prognosis is excellent. If the scan shows large areas of destroyed pancreas, the prognosis is poor.

When acute pancreatitis is mild, the death rate is about 5% or less. However, in pancreatitis with severe damage and bleeding, or when the inflammation is not confined to the pancreas, the death rate can be as high as 10 to 50%. Death during the first several days of acute pancreatitis is usually caused by failure of the heart, lungs, or kidneys. Death after the first week is usually caused by pancreatic infection or by a pseudocyst that bleeds or ruptures.

Treatment

Treatment of mild pancreatitis usually involves short-term hospitalization where analgesics are given for pain relief and the person fasts to try to rest the pancreas. Usually, normal eating can resume after 2 to 3 days without further treatment.

People with moderate to severe pancreatitis need to be hospitalized. They must initially avoid food and liquids, because eating and drinking stimulate the pancreas. Symptoms such as pain and nausea are controlled with intravenous drugs. Intravenous fluids are given as well. People with severe acute pancreatitis are admitted to an intensive care unit, where vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, and rate of breathing) and urine production can be monitored continuously. Blood samples are repeatedly drawn to monitor various components of the blood, including hematocrit, sugar (glucose) levels, electrolyte levels, white blood cell count, and amylase and lipase levels. A tube may be inserted through the nose and into the stomach (nasogastric tube) to remove fluid and air, particularly if nausea and vomiting persist and gastrointestinal ileus is present. Nutrition is given intravenously, via a nasogastric tube, or by both means.

For people with a drop in blood pressure or who are in shock, blood volume is carefully maintained with intravenous fluids, and heart function is closely monitored. Some people need supplemental oxygen, and the most seriously ill require a ventilator.

When acute pancreatitis results from gallstones, treatment depends on the severity. If the pancreatitis is mild, removal of the gallbladder can usually be delayed until symptoms subside. Severe pancreatitis caused by gallstones can be treated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP—see art on page 213). Although more than 80% of people with gallstone pancreatitis pass the stone spontaneously, ERCP with stone removal is usually needed for people who do not improve over the initial 24 hours of hospitalization and who have an infection of the bile duct system (cholangitis).

Chronic Pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis is long-standing inflammation of the pancreas that results in irreversible deterioration of pancreatic structure and function.

Abdominal pain may be persistent or intermittent.

Abdominal pain may be persistent or intermittent.

The diagnosis is usually based on the symptoms, but blood tests may be helpful.

The diagnosis is usually based on the symptoms, but blood tests may be helpful.

Treatment involves allowing the pancreas to rest and taking drugs to relieve the pain.

Treatment involves allowing the pancreas to rest and taking drugs to relieve the pain.

In the United States, most chronic pancreatitis has no clear cause (idiopathic) or is due to alcohol abuse. Other less common causes include a hereditary predisposition; hyperparathyroidism (see box on page 937); and an obstruction of the pancreatic duct caused by a narrowing of the duct, gallstones, or cancer. Rarely, an attack of severe acute pancreatitis makes the pancreatic duct so narrow that chronic pancreatitis results. In tropical countries (for example, India, Indonesia, and Nigeria), chronic pancreatitis of unknown cause occurs among children and young adults.

Symptoms

Symptoms of chronic pancreatitis may be identical to those of acute pancreatitis and generally fall into two patterns. In one pattern, a person has persistent midabdominal pain that varies in intensity. In this pattern, a complication of chronic pancreatitis, such as an inflammatory mass, a cyst, or even pancreatic cancer, is more likely. In the second pattern, a person has intermittent flare-ups (bouts or attacks) of pancreatitis with symptoms similar to those of mild to moderate acute pancreatitis. The pain sometimes is severe and lasts for many hours or several days. With either pattern, as chronic pancreatitis progresses, cells that secrete the digestive enzymes are slowly destroyed, so eventually the pain may stop.

As the number of digestive enzymes decreases (a condition called pancreatic insufficiency), food is inadequately broken down. Food that is inadequately broken down is not absorbed properly (malabsorption), and the person may produce bulky, unusually foul-smelling, greasy stools (steatorrhea). The stool is light-colored and may even contain oil droplets. Undigested muscle fibers may also be found in the feces. The inadequate absorption of food also leads to weight loss. Eventually, the insulin-secreting cells of the pancreas may be destroyed, gradually leading to diabetes.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Anyone who has chronic pancreatitis should avoid alcohol.

Diagnosis

A doctor suspects chronic pancreatitis because of a person’s symptoms or history of acute pancreatitis flare-ups or alcohol abuse. Blood tests are less useful in diagnosing chronic pancreatitis than in diagnosing acute pancreatitis, but they may indicate elevated levels of amylase and lipase. Also, blood tests can be used to check the level of sugar (glucose) in the blood, which may be elevated.

Computed tomography (CT) may be done to show changes of chronic pancreatitis. When available, many doctors now perform a special magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) test called magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) instead of CT. MRCP shows the bile and pancreatic ducts more clearly than does CT.

People with chronic pancreatitis are at increased risk of pancreatic cancer. Worsening of symptoms, especially narrowing of the pancreatic duct, makes doctors suspect cancer. In such cases, a doctor is likely to do an MRI scan, CT scan, or endoscopic study.

Treatment

Treatment of repeated flare-ups of chronic pancreatitis is similar to that of acute pancreatitis. Even if alcohol is not the cause, all people with chronic pancreatitis should avoid drinking alcohol. Avoiding all food and receiving only intravenous fluids can rest the pancreas and intestine and may relieve a painful flare-up. In addition, opioid analgesics (see page 642) are sometimes needed to relieve the pain. Too often, these measures do not relieve the pain, requiring increased amounts of opioids, which may put the person at risk of addiction. Medical treatment of chronic pancreatic pain is often unsatisfactory.

Later, eating four or five meals a day consisting of food low in fat may help reduce the frequency and intensity of the flare-ups. If pain continues, a doctor searches for complications, such as an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas or a pseudocyst (a collection of pancreatic enzymes, fluid, and tissue debris resembling a cyst). An inflammatory mass may require surgical treatment. A pancreatic pseudocyst that causes pain as it expands may have to be drained (decompressed).

If the person has continuing pain and no complications, the doctor may recommend injecting a combination of the anesthetic lidocaine and corticosteroids into the nerves from the pancreas to block pain impulses from reaching the brain. If this procedure does not work, which is frequently the case, surgical treatment may be an option if the pancreatic ducts are dilated or if there is an inflammatory mass in one region of the pancreas. For instance, when the pancreatic duct is dilated, creating a bypass from the pancreas to the small intestine relieves the pain in about 70 to 80% of people. When the duct is not dilated, part of the pancreas may have to be removed. Removing part of the pancreas means that cells that produce insulin are removed as well, and diabetes may develop. Doctors reserve surgical treatment for people who have stopped using alcohol and who can manage any diabetes that develops. For people who no longer produce adequate digestive enzymes, taking tablets or capsules of pancreatic enzyme extracts with meals can make the stool less greasy and improve food absorption, but these problems are rarely eliminated. If necessary, a histamine-2 (H2) blocker or a proton pump inhibitor (drugs that reduce or prevent the production of stomach acid) may be taken with the pancreatic enzymes. With such treatment, the person usually gains some weight, has fewer daily bowel movements, has no more oil droplets in the stool, and generally feels better. If these measures are ineffective, the person can try decreasing fat intake. Supplements of the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) also may be needed.

Oral hypoglycemic drugs rarely can be used in the treatment of diabetes caused by chronic pancreatitis. Insulin is generally needed but can cause a problem, because affected people also have decreased levels of glucagon, which is a hormone that acts to balance the effects of insulin. An excess of insulin in the bloodstream causes low sugar levels in the blood, which can result in a hypoglycemic coma (see page 1015).