CHAPTER 32

Biology of the Liver and Gallbladder

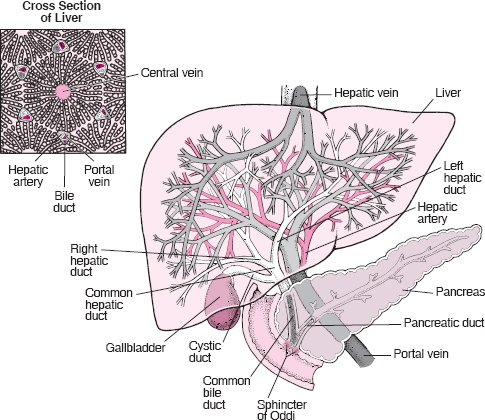

Located in the upper right portion of the abdomen, the liver and gallbladder are interconnected by ducts known as the biliary tract, which drains into the first segment of the small intestine (the duodenum). Although the liver and gallbladder participate in some of the same functions, they are very different.

Liver

The wedge-shaped liver is the largest—and, in some ways, the most complex—organ in the body. It serves as the body’s chemical factory, performing many vital functions, from regulating the levels of chemicals in the body to producing substances that make blood clot (clotting factors) during bleeding.

Functions of the Liver

The liver manufactures about half of the body’s cholesterol. The rest comes from food. Most of the cholesterol made by the liver is used to make bile, a greenish yellow, thick, sticky fluid that aids in digestion. Cholesterol is also needed to make certain hormones, including estrogen, testosterone, and the adrenal hormones, and is a vital component of every cell membrane. The liver manufactures other substances, including proteins needed by the body for its functions. For example, clotting factors are proteins needed to stop bleeding. Albumin is a protein needed to maintain fluid pressure in the bloodstream.

Sugars are stored in the liver as glycogen and then broken down and released into the bloodstream as glucose when needed—for example, during sleep when a person spends many hours without eating and sugar levels in the blood become too low.

The liver also breaks down harmful or toxic substances (toxins) absorbed from the intestine or manufactured elsewhere in the body and then excretes them as harmless by-products into the bile or blood. By-products excreted into bile enter the intestine, then leave the body in stool. By-products excreted into blood are filtered out by the kidneys, then leave the body in urine. The liver also chemically alters (metabolizes) drugs (see page 84), often making them inactive or easier to excrete from the body.

Blood Supply of the Liver

The liver receives blood directly from the intestines, as well as from the heart, as do all other organs. Blood from the intestines contains nearly everything absorbed by the intestines, including nutrients, drugs, and sometimes toxins. This blood flows through tiny capillaries in the intestinal wall into the portal vein, which enters the liver. The blood then flows through a latticework of tiny channels inside the liver, where digested nutrients and toxins are processed.

The hepatic artery brings blood to the liver from the heart. This blood carries oxygen to the liver tissues as well as cholesterol and other substances for processing. Blood from the intestines and heart then mix together in the liver tissues and flow back to the heart through the hepatic vein.

Gallbladder and Biliary Tract

The gallbladder is a small, pear-shaped, muscular storage sac that holds bile. Bile is a greenish yellow, thick, sticky fluid. It consists of bile salts, electrolytes (dissolved charged particles, such as sodium and bicarbonate), bile pigments, cholesterol, and other fats (lipids). Bile has two main functions: aiding in digestion and eliminating certain waste products (mainly hemoglobin and excess cholesterol) from the body. Bile salts aid in digestion by making cholesterol, fats, and fat-soluble vitamins easier to absorb from the intestine. The main pigment in bile, bilirubin, is a waste product that is formed from hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen in the blood) and is excreted in bile. Hemoglobin is released when old or damaged red blood cells are destroyed.

Bile flows out of the liver through the left and right hepatic ducts, which come together to form the common hepatic duct. This duct then joins with a duct connected to the gallbladder, called the cystic duct, to form the common bile duct. The common bile duct enters the small intestine at the sphincter of Oddi (a ring-shaped muscle), located a few inches below the stomach.

About half the bile secreted between meals flows directly through the common bile duct into the small intestine. The rest of the bile is diverted through the cystic duct into the gallbladder to be stored. In the gallbladder, up to 90% of the water in bile is absorbed into the bloodstream, making the remaining bile very concentrated. When food enters the small intestine, a series of hormonal and nerve signals triggers the gallbladder to contract and the sphincter of Oddi to relax and open. Bile then flows from the gallbladder into the small intestine to mix with food contents and perform its digestive functions.

After bile enters and passes down the small intestine, about 90% of bile salts are reabsorbed into the bloodstream through the wall of the lower small intestine. The liver extracts these bile salts from the blood and resecretes them back into the bile. Bile salts go through this cycle about 10 to 12 times a day. Each time, small amounts of bile salts escape absorption and reach the large intestine, where they are broken down by bacteria. Some bile salts are reabsorbed in the large intestine. The rest are excreted in the stool.

View of the Liver and Gallbladder

Liver cells produce bile, which flows into small channels called bile canaliculi. These small channels drain into bile ducts. The ducts join to form larger and larger channels and eventually form the left and right hepatic ducts, which join to form the common hepatic duct. The common hepatic duct joins with a duct connected to the gallbladder, called the cystic duct, to form the common bile duct. The common bile duct is joined by the pancreatic duct just before it enters the small intestine at the sphincter of Oddi.

The gallbladder, although useful, is not necessary. If the gallbladder is removed (for example, in a person with cholecystitis), bile can move directly from the liver to the small intestine.

Hard masses consisting mainly of cholesterol (gallstones) may form in the gallbladder or bile ducts. Gallstones usually cause no symptoms. However, gallstones may block the flow of bile from the gallbladder, causing pain (biliary colic) or inflammation. They may also migrate from the gallbladder to the bile duct, where they can block the normal flow of bile to the intestine, causing jaundice (a yellowish discoloration of the skin and whites of the eyes) in addition to pain and inflammation. The flow of bile can also be blocked by tumors. Other causes of blocked flow are less common.

Effects of Aging

A number of structural and microscopic changes occur as the liver ages. For example, the color of the liver changes from lighter to darker brown. Its size and blood flow decrease. However, liver function test results generally remain normal.

The ability of the liver to metabolize many substances decreases with aging. Thus, some drugs are not inactivated as quickly in older people as they are in younger people. As a result, a drug dose that would not have side effects in younger people may cause dose-related side effects in older people (see page 1896). Thus, drug dosages often need to be decreased in older people. Also, the liver’s ability to withstand stress decreases. Thus, substances that are toxic to the liver can cause more damage in older people than in younger people. Repair of damaged liver cells is also slower in older people.

The production and flow of bile decrease with aging. As a result, gallstones are more likely to form.