CHAPTER 48

Obstruction of the Urinary Tract

An obstruction anywhere along the urinary tract—from the kidneys, where urine is produced, to the urethra, through which urine leaves the body—can increase pressure inside the urinary tract and slow the flow of urine. An obstruction may occur suddenly or develop slowly over days, weeks, or even months. An obstruction may completely or only partially block part of the urinary tract.

Urinary tract obstruction can make the kidneys distend (dilate). Distention damages the kidneys. Although the kidneys can usually recover if the obstruction is relieved quickly, permanent damage may occur. Severe damage can result in loss of kidney function (kidney failure). Obstruction can also lead to stone formation and urinary tract infections. An infection may develop because bacteria that enter the urinary tract are not flushed out when the flow of urine is obstructed.

Hydronephrosis

Hydronephrosis is distention (dilation) of the kidney with urine, caused by backward pressure on the kidney when the flow of urine is obstructed.

Kidney stones are common causes of urinary tract obstruction.

Kidney stones are common causes of urinary tract obstruction.

When hydronephrosis occurs quickly, people may have excruciating pain, most often in the flank (the area between the ribs and the hips).

When hydronephrosis occurs quickly, people may have excruciating pain, most often in the flank (the area between the ribs and the hips).

When hydronephrosis occurs more gradually, people may have no symptoms or experience attacks of dull, aching discomfort in the flank.

When hydronephrosis occurs more gradually, people may have no symptoms or experience attacks of dull, aching discomfort in the flank.

Doctors initially use bladder catheterization (or ultrasonography) to detect hydronephrosis, and they may use ultrasonography or another imaging test to determine the site of the blockage.

Doctors initially use bladder catheterization (or ultrasonography) to detect hydronephrosis, and they may use ultrasonography or another imaging test to determine the site of the blockage.

Treatment depends on the cause of the obstruction.

Treatment depends on the cause of the obstruction.

Normally, urine flows out of the kidneys at extremely low pressure. If the flow of urine is obstructed, urine backs up behind the point of blockage, eventually reaching the small tubes of the kidney and its collecting area (renal pelvis), distending the kidney and increasing the pressure on its internal structures. The elevated pressure from obstruction may ultimately damage the kidney and can result in loss of its function. When the flow of urine is obstructed, urinary tract infections are fairly common and stones are more likely to form. If both kidneys are obstructed, kidney failure may result.

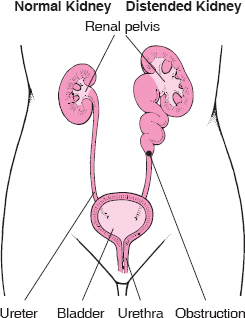

Hydronephrosis: A Distended Kidney

In hydronephrosis, the kidney is distended because the flow of urine is obstructed and urine backs up in the kidney’s small tubes and central collecting area (renal pelvis).

Long-standing distention of the renal pelvis and ureter can also inhibit the rhythmic muscular contractions that normally move urine down the ureter from the kidney to the bladder (peristalsis). Scar tissue may then replace the normal muscular tissue in the walls of the ureter, resulting in permanent damage.

Causes

Hydronephrosis commonly results from an obstruction located at the junction of the ureter and renal pelvis (ureteropelvic junction). Causes of this type of obstruction include the following:

Structural abnormalities—for example, a birth defect in which the insertion of the ureter into the renal pelvis is too high or there is inadequate development of the ureteral muscles (congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction)

Structural abnormalities—for example, a birth defect in which the insertion of the ureter into the renal pelvis is too high or there is inadequate development of the ureteral muscles (congenital ureteropelvic junction obstruction)

Kinking at the ureteropelvic junction resulting from a kidney shifting downward (ptosis of the kidney)

Kinking at the ureteropelvic junction resulting from a kidney shifting downward (ptosis of the kidney)

Stones (calculi) or a blood clot in the renal pelvis

Stones (calculi) or a blood clot in the renal pelvis

Compression of the ureter by bands of fibrous tissue, an abnormally located artery or vein, or a tumor

Compression of the ureter by bands of fibrous tissue, an abnormally located artery or vein, or a tumor

Hydronephrosis can also result from an obstruction below the ureteropelvic junction or from back-flow (reflux) of urine from the bladder. Causes of this type of obstruction include the following:

Stones in the ureter

Stones in the ureter

Blood clot in the ureter

Blood clot in the ureter

Tumors in or near the ureter

Tumors in or near the ureter

Narrowing of the ureter resulting from a birth defect, an injury, an infection, radiation therapy, or surgery

Narrowing of the ureter resulting from a birth defect, an injury, an infection, radiation therapy, or surgery

Disorders of the muscles or nerves in the ureter or bladder

Disorders of the muscles or nerves in the ureter or bladder

Formation of fibrous tissue in or around the ureter resulting from surgery, radiation therapy, or drugs (especially methysergide)

Formation of fibrous tissue in or around the ureter resulting from surgery, radiation therapy, or drugs (especially methysergide)

Bulging of the lower end of the ureter into the bladder (ureterocele)

Bulging of the lower end of the ureter into the bladder (ureterocele)

Cancers of the bladder, cervix, uterus, prostate, or other pelvic organs

Cancers of the bladder, cervix, uterus, prostate, or other pelvic organs

Obstruction that prevents urine flow from the bladder to the urethra, resulting from prostate enlargement (most often caused by a condition called benign prostatic hyperplasia—see page 1474) or rectal impaction with feces

Obstruction that prevents urine flow from the bladder to the urethra, resulting from prostate enlargement (most often caused by a condition called benign prostatic hyperplasia—see page 1474) or rectal impaction with feces

Abnormal contractions of the bladder resulting from a birth defect or a spinal cord or nerve injury

Abnormal contractions of the bladder resulting from a birth defect or a spinal cord or nerve injury

Hydronephrosis of both kidneys can occur during pregnancy as the enlarging uterus compresses the ureters. Hormonal changes during pregnancy may aggravate the problem by reducing the muscular contractions that normally move urine down the ureters. This condition, commonly called hydronephrosis of pregnancy, usually ends when the pregnancy ends, although the renal pelvis and ureters may remain somewhat distended afterward.

Symptoms

Symptoms depend on the cause, location, and duration of the obstruction. When the obstruction begins quickly (acute hydronephrosis), it usually causes renal colic—an excruciating, intermittent pain in the flank (the area between the ribs and hip) on the affected side. Obstruction on one side does not reduce urine flow. Obstruction can stop or reduce urine flow if blockage affects the ureters from both kidneys or if it affects the urethra. Obstruction of the urethra or bladder outlet may cause pain, pressure, and distention of the bladder.

People who have slowly progressive (chronic) hydronephrosis may have no symptoms, or they may have attacks of dull, aching discomfort in the flank on the affected side. Sometimes a kidney stone temporarily blocks the ureter and causes painful hydronephrosis that occurs intermittently.

Hydronephrosis may cause vague intestinal symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. These symptoms sometimes occur in children when hydronephrosis results from a birth defect in which the junction of the ureter and renal pelvis is too narrow (ureteropelvic junction obstruction).

People who have urinary tract infections may have pus in the urine, fever, and discomfort in the area of the bladder or kidneys.

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis is important, because most cases of obstruction can be corrected and because a delay in treatment can lead to irreversible kidney damage. Doctors may suspect hydronephrosis because of a person’s symptoms and sometimes because of findings discovered during a physical examination. A distended kidney can occasionally be felt in the flank, particularly if the kidney is greatly enlarged in an infant or a child or a thin adult. A distended bladder can sometimes be felt in the lower part of the abdomen just above the pubic bone.

Doctors depend on testing to make the diagnosis. Bladder catheterization (insertion of a hollow, flexible tube through the urethra) is often the first diagnostic test done in people with renal colic, pelvic pressure, or distention. If the catheter drains a large amount of urine from the bladder, then either the bladder outlet or the urethra is obstructed. Many doctors do ultrasonography to determine whether the bladder is filled with a large amount of urine before doing bladder catheterization.

If the presence or site of obstruction is in doubt, various imaging tests can be done to identify evidence of obstruction such as hydronephrosis or a site of blockage. For example, ultrasonography is a very useful test in most people (particularly children and pregnant women) because it is fairly accurate and does not expose the person to any radiation. Computed tomography (CT) scanning is an alternative. It is rapid and highly accurate, particularly at identifying stones. Other imaging tests, such as intravenous urography, may be performed to identify the site of obstruction, if it is not visible with ultrasonography or CT.

An endoscope (a rigid or flexible telescope) is sometimes used to look at possible sites of obstruction as closely as possible. An endoscope can be used to examine the urinary tract.

Blood and urine tests are done. Blood test results are usually normal, but tests may reveal high levels of urea nitrogen (sometimes called BUN), creatinine, or both if obstruction affects both kidneys. Results from an analysis of urine (urinalysis) are usually normal, but white blood cells and red blood cells may be present when a stone or a cancer is the cause of obstruction or when the obstruction is complicated by an infection.

Prognosis

Permanent kidney damage is unlikely to result unless both kidneys are obstructed for at least a few weeks. The prognosis is less certain for chronic hydronephrosis.

Treatment

Treatment usually aims to relieve the cause of obstruction. For example, if the urethra is obstructed because of an enlarged or cancerous prostate, treatment can include drugs, such as hormone therapy for prostate cancer (see page 1480), surgery, or enlargement of the urethra with dilators. Other treatments, such as lithotripsy or endoscopic surgery, may be needed for stones that block the flow of urine. If the cause of obstruction cannot be rapidly corrected, particularly if there is infection, kidney failure, or severe pain, the urinary tract is drained. In acute hydronephrosis, urine that has accumulated above the obstruction can be drained with a soft tube inserted through the skin into the kidney (nephrostomy tube) or by insertion of a soft plastic tube that connects the bladder with the kidney (ureteral stent). Complications of nephrostomy tubes or ureteral stents can include displacement of the tube, infection, and discomfort.

Urgent relief of chronic hydronephrosis is usually not required. Complications of hydronephrosis, such as urinary tract infections and kidney failure, if present, are treated promptly.

Stones in the Urinary Tract

Stones (calculi) are hard masses that form anywhere in the urinary tract and may cause pain, bleeding, obstruction of the flow of urine, or an infection.

Tiny stones may cause no symptoms, but larger stones can cause excruciating pain in the area between the ribs and hips.

Tiny stones may cause no symptoms, but larger stones can cause excruciating pain in the area between the ribs and hips.

Usually, an imaging test and an analysis of urine are done to diagnose stones.

Usually, an imaging test and an analysis of urine are done to diagnose stones.

Sometimes, stone formation can be prevented by changing the diet.

Sometimes, stone formation can be prevented by changing the diet.

Stones that do not pass on their own are removed with lithotripsy or an endoscopic technique.

Stones that do not pass on their own are removed with lithotripsy or an endoscopic technique.

Depending on where a stone forms, it may be called a kidney stone, ureteral stone, or bladder stone. The process of stone formation is called urolithiasis, renal lithiasis, or nephrolithiasis.

Every year, about 1 of 1,000 adults in the United States is hospitalized because of stones in the urinary tract. Stones are more common among middle-aged and older adults and men. Stones vary in size from too small to be seen with the naked eye to 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) or more in diameter. A large so-called staghorn stone may fill almost the entire renal pelvis (small tubes of the kidney and its collecting area) and the tubes that drain into it (calices).

A urinary tract infection may result when bacteria become trapped in urine that pools above a blockage. When stones block the urinary tract for a long time, urine backs up in the tubes inside the kidney, producing excessive pressure that can distend the kidney (hydronephrosis) and eventually damage it.

Causes

Stones may form because the urine becomes too saturated with salts that can form stones or because the urine lacks the normal inhibitors of stone formation. Citrate is such an inhibitor, because it normally binds with the calcium that is often involved in forming stones. About 80% of the stones are composed of calcium, and the remainder are composed of various substances, including uric acid, cystine, and struvite. Stones are more common among people with certain disorders (for example, hyperparathyroidism and short bowel syndrome) and among people whose diet is very high in protein or vitamin C or who do not consume enough water or calcium. People who have a family history of stone formation are more likely to have calcium stones and to have them more often. Struvite stones—a mixture of magnesium, ammonium, and phosphate—are also called infection stones, because they form only in infected urine.

Symptoms

Stones, especially tiny ones, may not cause any symptoms. Stones in the bladder may cause pain in the lower abdomen. Stones that obstruct the ureter or renal pelvis or any of the kidney’s drainage tubes may cause back pain or renal colic. Renal colic is characterized by an excruciating intermittent pain, usually in the flank (the area between the ribs and hip), that spreads across the abdomen, often to the genital area and inner thigh. The pain tends to come in waves, gradually increasing to a peak intensity, then fading, over about 20 to 60 minutes. The pain may radiate down the abdomen toward the groin or testis or vulva.

Other symptoms include nausea and vomiting, restlessness, sweating, and blood in the urine. A person may have an urge to urinate frequently, particularly as a stone passes down the ureter. Chills, fever, and abdominal distention sometimes occur.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

People who have recurrent kidney stones should consider limiting the number of CT scans they get to prevent excessive radiation exposure.

Diagnosis

Doctors usually suspect stones in people with renal colic. Sometimes doctors suspect stones in people with tenderness over the back and groin or pain in the genital area without an obvious cause. Occasionally, the symptoms and physical examination findings are so distinctive that no additional tests are needed, particularly in people who have had urinary tract stones before. However, most people are in so much pain and have symptoms and findings that make other causes for the pain seem likely enough that testing is necessary to exclude these other causes. Helical (also called spiral) computed tomography (CT) that is done without the use of radiopaque contrast material is usually the best diagnostic procedure. CT can locate a stone and also indicate the degree to which the stone is blocking the urinary tract. CT can also detect many other disorders that can cause pain similar to the pain caused by stones. The disadvantage of CT is that it exposes people to radiation. Still, this risk seems prudent when possible causes include another serious disorder that would be diagnosed by CT, such as an aortic aneurysm or appendicitis. Ultrasonography is an alternative to CT and does not expose people to radiation. However, ultrasonography, compared with CT, more often misses small stones (especially when located in the ureter), the location of urinary tract blockage, and other, serious disorders that could be causing the symptoms.

Urinalysis is usually done. It may show blood or pus in the urine whether or not symptoms are present.

For people with diagnosed stones, doctors often do tests to determine the type of stones. People should attempt to retrieve stones that are passed. They can retrieve stones by straining all urine. Stones found can be analyzed. Depending on the type of stone, urine tests and tests of blood chemistries and hormone levels may be necessary.

Prevention

Measures to prevent the formation of new stones vary, depending on the composition of the existing stones.

Drinking large amounts of fluids—8 to 10 ten-ounce (300-milliliter) glasses a day—is recommended for prevention of all stones, although it is not clear whether and how much this helps. Many people with calcium stones have a condition called hypercalciuria, in which excess calcium is excreted in the urine. For them, a diet that is low in sodium and high in potassium may also help. Calcium intake should be about normal—1,000 to 1,500 milligrams daily (see page 933). Restricting dietary protein from red meat may help reduce the risk of stone formation. Thiazide diuretics, such as chlorthalidone or indapamide, reduce the concentration of calcium in the urine and help prevent the formation of new stones in such people. Potassium citrate may be given to increase a low urine level of citrate, a substance that inhibits calcium stone formation.

A high level of oxalate in the urine, which contributes to calcium stone formation, may result from excess consumption of foods high in oxalate, such as rhubarb, spinach, cocoa, nuts, pepper, and tea, or from certain intestinal disorders. Calcium citrate, cholestyramine, and a low-oxalate, low-fat diet may help to reduce urinary oxalate levels in some people. Sometimes pyridoxine decreases the amount of oxalate the body makes.

In rare cases, when calcium stones result from hyperparathyroidism, sarcoidosis, vitamin D toxicity, renal tubular acidosis, or cancer, the underlying disorder must be treated.

For stones that contain uric acid, a diet low in red meat is recommended, because red meat increases the level of uric acid in the urine. If this is not effective, allopurinol may be given to reduce the production of uric acid. Potassium citrate should be given to all people who have uric acid stones to make the urine alkaline, because uric acid stones form when urine acidity increases. Maintaining a large fluid intake is also very important.

For stones made of cystine, urinary cystine levels must be kept low by maintaining a large fluid intake and sometimes taking α-mecaptopropionylglycine (tiopronin) or penicillamine.

People with recurrent struvite stones may need to take antibiotics continually to prevent urinary tract infections. Acetohydroxamic acid may also be helpful.

Treatment

Small stones that are not causing symptoms, obstruction, or an infection usually do not need to be treated. Drinking plenty of fluids or receiving large amounts of fluids intravenously has been recommended to help stones pass, but it is not clear that this approach is helpful. Drugs that may help the stone pass include alpha-adrenergic blockers (such as tamsulosin) and calcium channel blockers (such as diltiazem, nifedipine, and verapamil). Once a stone has passed, no other immediate treatment is needed. The pain of renal colic may be relieved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or opioids.

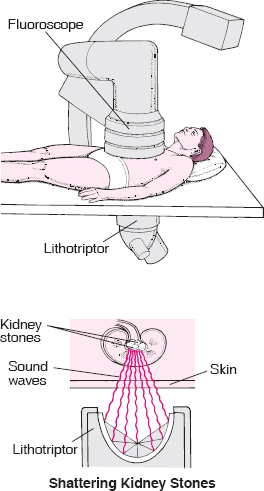

Often, a stone in the renal pelvis or uppermost part of the ureter that is 1/2 inch (1 centimeter) or less in diameter can be broken up by shock waves directed at the body by a sound wave generator (a procedure called extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy). The pieces of stone are then passed in the urine. Sometimes, a stone is removed with grasping forceps using an endoscope (viewing tube) through a small incision in the skin, or the stone can be shattered into fragments using a probe from a lithotripsy machine and then the pieces are passed in the urine.

Small stones in the lower part of the ureter that require removal may be removed with a small, flexible scope (called a ureteroscope, a kind of endoscope) that is inserted into the urethra and through the bladder. In some instances, the ureteroscope can also be used with a device to break up stones into smaller pieces that can be removed with the ureteroscope or passed in the urine (a procedure called intracorporeal lithotripsy). Most commonly, the device is a laser. When a laser is used, the procedure is called holmium laser lithotripsy.

Uric acid stones may sometimes be dissolved gradually by making the urine more alkaline (for example, with potassium citrate taken for 4 to 6 months by mouth), but other types of stones cannot be dissolved this way. Sometimes, larger stones that are causing an obstruction may need to be removed surgically.

Removing a Stone With Sound Waves

Kidney stones can sometimes be broken up by sound waves produced by a lithotriptor in a procedure called extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. After an ultrasound device or fluoroscope is used to locate the stone, the lithotriptor is placed against the back, and the sound waves are focused on the stone, shattering it. Then the person drinks fluids to flush the stone fragments out of the kidney, to be eliminated in the urine. Sometimes blood appears in the urine or the abdomen is bruised after the procedure, but serious problems are rare.

Struvite stones usually need to be removed by endoscopic surgery. Antibiotics are not helpful for urinary tract infections until the stones are removed.