CHAPTER 62

Pericardial Disease

Pericardial disease affects the pericardium, which is the flexible two-layered sac that envelops the heart.

The pericardium helps keep the heart in position, prevent the heart from overfilling with blood, and protect the heart from being damaged by chest infections. However, the pericardium is not essential to life; if the pericardium is removed, there is little measurable effect on the heart’s performance.

Normally, the pericardium contains just enough lubricating fluid between its two layers for them to slide easily over one another. There is very little space between the two layers. However, in some disorders, extra fluid accumulates in this space (called the pericardial space), causing it to expand.

Rarely, the pericardium is missing at birth or has defects, such as weak spots or holes. These defects can be dangerous because the heart or a major blood vessel may bulge (herniate) through a hole in the pericardium and become trapped. In such cases, death can occur in minutes. Therefore, these defects are usually surgically repaired; if repair is not feasible, the whole pericardium may be removed. Other diseases of the pericardium may result from infections, injuries, or spread of cancer.

Acute Pericarditis

Acute pericarditis is inflammation of the pericardium that begins suddenly, is often painful, and causes fluid and blood components such as fibrin, red blood cells, and white blood cells to pour into the pericardial space.

Infection and other conditions that can irritate the pericardium cause pericarditis.

Infection and other conditions that can irritate the pericardium cause pericarditis.

Fever and chest pain, which may feel like a heart attack, are common symptoms.

Fever and chest pain, which may feel like a heart attack, are common symptoms.

Diagnosis is based on symptoms and by hearing a telltale sound when listening to the heartbeat with a stethoscope.

Diagnosis is based on symptoms and by hearing a telltale sound when listening to the heartbeat with a stethoscope.

People are hospitalized and given drugs to reduce pain and inflammation.

People are hospitalized and given drugs to reduce pain and inflammation.

Acute pericarditis usually results from infection or other conditions that irritate the pericardium. Infection is usually due to a virus but may be caused by bacteria, parasites (including protozoa), or fungi.

In some inner city hospitals, AIDS is the most common cause of pericarditis with extra fluid in the pericardial space (pericardial effusion). In people who have AIDS, a number of infections, including tuberculosis, may result in pericarditis. Pericarditis due to tuberculosis (tuberculous pericarditis) accounts for less than 5% of cases of acute pericarditis in the United States but accounts for the majority of cases in some areas of India and Africa.

Other conditions can irritate the pericardium and thus can cause acute pericarditis. These conditions include a heart attack, heart surgery, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, kidney failure, injury, cancer (such as leukemia and, in people with AIDS, Kaposi’s sarcoma), rheumatic fever, an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism), radiation therapy, and leakage of blood from an aortic aneurysm (a bulge in the wall of the aorta). After a heart attack, acute pericarditis develops during the first day or two in 10 to 15% of people and after about 10 days to 2 months in 1 to 3%. Acute pericarditis may occur as a side effect of certain drugs, including anticoagulants (such as warfarin and heparin), penicillin, procainamide (an antiarrhythmic drug), phenytoin (an anticonvulsant), and phenylbutazone (a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug).

Symptoms

Usually, acute pericarditis causes fever and chest pain, which typically extends to the left shoulder and sometimes down the left arm. The pain may be similar to that of a heart attack, except that it tends to be made worse by lying down, swallowing food, coughing, or even deep breathing. The accumulating fluid or blood in the pericardial space puts pressure on the heart, interfering with its ability to pump blood. If the pressure is too high, cardiac tamponade—a potentially fatal condition—may occur.

Acute pericarditis due to tuberculosis begins insidiously, sometimes without obvious symptoms of lung infection. It may produce fever and symptoms of heart failure, such as weakness, fatigue, and difficulty breathing. Cardiac tamponade may occur.

Acute pericarditis due to a viral infection is usually painful but short-lived and has no lasting effects.

When acute pericarditis develops in the first day or two after a heart attack, symptoms of pericarditis are seldom noticed, because symptoms of the heart attack are the main concern (see page 411). Pericarditis that develops about 10 days to 2 months after a heart attack is usually accompanied by Dressler’s syndrome (post-myocardial infarction syndrome), which includes fever, pericardial effusion (extra fluid in the pericardial space), pleurisy (inflammation of the pleura, which are the membranes covering the lungs), pleural effusion (fluid between the two layers of the pleura), and joint pain.

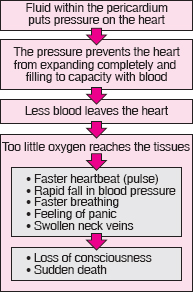

Cardiac Tamponade: The Most Serious Complication of Pericarditis

Cardiac tamponade is caused by accumulation of fluid or blood between the two layers of the pericardium. The accumulating fluid or blood puts pressure on the heart, interfering with its ability to pump blood. As a result, when a person breathes in, blood pressure may fall rapidly to abnormally low levels and the pulse may correspondingly weaken. When a person breathes out, blood pressure increases and the pulse becomes stronger. This exaggeration in the variation in blood pressure and pulse that occurs with breathing is called a paradoxical pulse. Later, as the heart is compressed more, the blood pressure remains low, and the person may pass out or die.

The most common causes of such significant fluid accumulation are cancer, heart injury, or heart surgery. Viral and bacterial pericardial infections and kidney failure are other common causes.

Echocardiography (which uses ultrasound waves to produce an image of the heart) may be used to confirm the diagnosis. This procedure can detect characteristic changes, such as compression of the heart and the variations in blood flow in the heart that occur with breathing.

Cardiac tamponade is usually a medical emergency. Doctors treat it immediately by removing fluid from the pericardium using a needle or catheter inserted through the chest wall to relieve the pressure in a procedure called pericardiocentesis. When time permits, fluid removal is closely monitored using echocardiography. Fluid may be surgically drained using a balloon-tipped catheter inserted through the skin (a procedure called percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy) or using a tube inserted through a small incision in the chest (a procedure called subxiphoid limited pericardiotomy). If the cause of pericarditis is unknown, doctors may send a sample of the fluid or a piece of tissue removed from the pericardium for examination under a microscope. This examination may provide information that helps identify the cause.

After the pressure is relieved, the person is usually kept in the hospital in case cardiac tamponade recurs. The person is usually monitored for 24 hours. The length of the hospital stay depends on the cause of tamponade. If a drain is in place, the person stays in the hospital until no more drainage occurs and the drain is removed.

If cardiac tamponade recurs, the same procedures may be performed again, or a different procedure may be tried. Other procedures include injection of a solution that obliterates the pericardium by causing scar tissue to form (sclerotherapy) and removal of the pericardium (pericardiectomy).

Diagnosis

Doctors can diagnose acute pericarditis based on the person’s description of the pain and the sounds heard by listening through a stethoscope placed on the person’s chest. Pericarditis can produce a crunching sound similar to the creaking of a leather shoe or a scratchy sound similar to the rustling of dry leaves (pericardial rub). Doctors can often diagnose pericarditis a few hours to a few days after a heart attack based on hearing these sounds.

A chest x-ray and echocardiography (a procedure that uses ultrasound waves to produce an image of the heart—see page 328) may be useful because they can usually detect too much fluid in the pericardial space. Echocardiography may suggest the cause—for example, cancer. Electrocardiography (ECG) may be performed. ECG results may suggest pericarditis, but distinguishing pericarditis from a heart attack based on ECG results may be difficult. Blood tests can detect some of the conditions that cause pericarditis—for example, leukemia, AIDS, other infections, rheumatic fever, and increased levels of urea in the blood resulting from kidney failure.

Treatment and Prognosis

Regardless of the cause, doctors usually hospitalize people with pericarditis, give them drugs that reduce inflammation and pain (such as aspirin, ibuprofen, or another nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug—see page 644), and watch for complications, particularly cardiac tamponade. Intense pain may require an opioid, such as morphine, or a corticosteroid, such as prednisone. Prednisone does not directly reduce pain but relieves it by reducing inflammation. Drugs that may cause pericarditis are discontinued whenever possible.

Further treatment of acute pericarditis varies, depending on the cause. For people who have kidney failure, increasing the frequency of dialysis usually results in improvement. People who have cancer may respond to chemotherapy or radiation therapy, but often the pericardium is surgically removed. If a bacterial infection is the cause, treatment consists of antibiotics and surgical drainage of pus from the pericardium.

Fluid may be drained from the pericardium by inserting a balloon-tipped catheter through the skin and inflating the balloon to create a hole (window) in the pericardium. This procedure, called percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy, is usually performed for effusions that are due to cancer or that recur. Alternatively, a small incision is made below the breast bone, and a piece of the pericardium is removed. Then a tube is inserted into the pericardial space. This procedure, called a subxiphoid pericardiotomy, is often performed for effusions due to bacterial infections. Both procedures require a local anesthetic, can be performed at the bedside, allow fluid to drain continuously, and are effective.

If pericarditis resulting from a virus, an injury, or an unidentified disorder recurs, aspirin, ibuprofen, or corticosteroids may provide relief. For some people, colchicine is effective. If drug treatment is ineffective, the pericardium is usually removed surgically.

When acute pericarditis occurs within the first few hours or days after a heart attack, treatment for the heart attack, including aspirin and stronger analgesics such as morphine, can usually reduce any discomfort due to pericarditis.

The prognosis for people who have pericarditis depends on the cause. When pericarditis is caused by a virus or when the cause is not apparent, recovery usually takes 1 to 3 weeks. Complications or recurrences can slow recovery. People with cancer that has invaded the pericardium rarely survive beyond 12 to 18 months.

Chronic Pericarditis

Chronic pericarditis is inflammation that begins gradually, is long-lasting, and results in fluid accumulation in the pericardial space or thickening of the pericardium.

Symptoms include shortness of breath, coughing, and fatigue.

Symptoms include shortness of breath, coughing, and fatigue.

Echocardiography is used to make the diagnosis.

Echocardiography is used to make the diagnosis.

The cause, if known, is treated, or rest, salt restriction, and diuretics may be used to relieve symptoms.

The cause, if known, is treated, or rest, salt restriction, and diuretics may be used to relieve symptoms.

Sometimes surgery to remove the pericardium is needed.

Sometimes surgery to remove the pericardium is needed.

There are two main types of chronic pericarditis. In chronic effusive pericarditis, fluid slowly accumulates in the pericardial space, between the two layers of the pericardium.

Chronic constrictive pericarditis is a rare disease that usually results when scarlike (fibrous) tissue forms throughout the pericardium. The fibrous tissue tends to contract over the years, compressing the heart. Thus, the heart does not enlarge as it does in most types of heart disease. Because higher pressure is needed to fill the compressed heart, pressure in the veins that return blood to the heart increases. Fluid accumulates in the veins, then leaks out, and accumulates in other areas of the body, such as under the skin.

Causes

Usually, the cause of chronic effusive pericarditis is unknown, but it may be cancer, tuberculosis, or an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism).

Usually, the cause of chronic constrictive pericarditis is also unknown. The most common known causes are viral infections and radiation therapy for breast cancer or lymphoma. Chronic constrictive pericarditis may also result from any condition that causes acute pericarditis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, a previous injury, heart surgery, or a bacterial infection. Previously, tuberculosis was the most common cause of chronic pericarditis in the United States, but today tuberculosis accounts for only 2% of cases. In Africa and India, tuberculosis is still the most common cause of all forms of pericarditis.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

People can actually live without a pericardium, but surgery to remove it is risky.

Symptoms

Symptoms include shortness of breath, coughing, and fatigue. Coughing occurs because the high pressure in the veins of the lungs forces fluid into the air sacs. Fatigue occurs because the abnormal pericardium interferes with the heart’s pumping action, so that the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs. Other common symptoms are accumulation of fluid in the abdomen (ascites) and in the legs (edema). Sometimes fluid accumulates in the space between the two layers of the pleura, the membranes covering the lungs (a condition called pleural effusion—see page 518). However, chronic pericarditis does not cause pain.

Chronic effusive pericarditis may produce few symptoms if fluid accumulates slowly. The reason is that the pericardium can stretch gradually, so that cardiac tamponade may not occur. However, if fluid accumulates rapidly, the heart can become compressed and cardiac tamponade may occur.

Diagnosis

Symptoms provide important clues that a person has chronic pericarditis, particularly if there is no other reason for reduced heart performance—such as high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, or a heart valve disorder.

Echocardiography (see page 328) is often performed to confirm the diagnosis. It can detect the amount of fluid in the pericardial space and the formation of fibrous tissue around the heart. It can confirm the presence of cardiac tamponade. Chest x-rays may detect calcium deposits in the pericardium. These deposits develop in nearly half of the people who have chronic constrictive pericarditis.

The diagnosis can be confirmed in one of two ways. Cardiac catheterization can be used to measure blood pressure in the heart chambers and major blood vessels. These measurements help doctors distinguish pericarditis from similar disorders. Alternatively, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) can be used to determine the thickness of the pericardium. Normally, the pericardium is less than 1/8 inch (3 millimeters) thick, but in chronic constrictive pericarditis, it is usually 1/4 inch (6 millimeters) thick or more.

A biopsy may be performed to help determine the cause of chronic pericarditis—for example, tuberculosis. A small sample of the pericardium is removed during exploratory surgery and examined under a microscope. Alternatively, a sample can be removed using a pericardioscope (a fiber-optic tube used to view the pericardium and to obtain tissue samples) inserted through an incision in the chest.

Treatment

Known causes of chronic effusive pericarditis are treated when possible. If heart function is normal, doctors take a wait-and-see approach. If the disorder causes symptoms or if an infection is suspected, surgical drainage may be performed (see page 392).

For people with chronic constrictive pericarditis, bed rest, restriction of salt in the diet, and diuretics (drugs that increase the excretion of fluid) may relieve symptoms. However, the only possible cure is surgical removal of the pericardium. Surgery cures about 85% of people. However, because the risk of death from surgery is 5 to 15%, most people do not have surgery unless the disease substantially interferes with daily activities. Surgery is not performed in the early stages of the disorder (before significant symptoms appear) or in the late stages (when symptoms occur at rest).