CHAPTER 76

Asthma

Asthma is a condition in which the airways narrow—usually reversibly—in response to certain stimuli.

Coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath that occur in response to specific triggers are the most common symptoms.

Coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath that occur in response to specific triggers are the most common symptoms.

Doctors confirm the diagnosis of asthma by doing pulmonary function tests.

Doctors confirm the diagnosis of asthma by doing pulmonary function tests.

To prevent attacks, people should avoid substances that trigger asthma and should take drugs that help keep airways open.

To prevent attacks, people should avoid substances that trigger asthma and should take drugs that help keep airways open.

During an asthma attack, people need to take a drug that quickly opens the airways.

During an asthma attack, people need to take a drug that quickly opens the airways.

Asthma affects more than 20 million people in the United States, and it is becoming more common. Although it is one of the most common chronic diseases of childhood, adults can also develop asthma, even at an old age. Asthma affects more than 6 million children and occurs more frequently in boys before puberty and in girls after puberty. It also occurs more frequently in blacks and Puerto Ricans. Although the number of people affected by asthma has increased, the number of deaths has decreased.

The reason for the increase in asthma in children is not known, but it may relate to more widespread use of vaccines and antibiotics, to the fact that children are spending more time indoors, or to both. Increased use of vaccines and antibiotics may have shifted the activity of a special subgroup of white blood cells (called lymphocytes) in the body from fighting infection to releasing chemical substances that promote the development of allergies. Alternatively, because children are spending more time indoors and living in better-insulated homes than they were in the past, the exposure to potentially allergic substances is increased. There are few data to support either theory.

The most important characteristic of asthma is narrowing of the airways that can be reversed. The airways of the lungs (the bronchi) are basically tubes with muscular walls (see page 444). Cells lining the bronchi have microscopic structures, called receptors. There are two main types of receptors: beta-adrenergic and cholinergic. These receptors sense the presence of specific substances and stimulate the underlying muscles to contract and relax, thus altering the flow of air. Beta-adrenergic receptors respond to chemicals such as epinephrine and make the muscles relax, thereby widening (dilating) the airways and increasing airflow. Cholinergic receptors respond to a chemical called acetylcholine, making the muscles contract, thereby decreasing airflow.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Coughing may be the only symptom of asthma.

Causes

Narrowing of the airways is often caused by abnormal sensitivity of cholinergic receptors, which cause the muscles of the airways to contract when they should not. Certain cells in the airways, particularly mast cells, are thought to be responsible for initiating the response. Mast cells throughout the bronchi release substances such as histamine and leukotrienes, which cause smooth muscle to contract, mucus secretion to increase, and certain white blood cells to migrate to the area. Eosinophils, a type of white blood cell found in the airways of people with asthma, release additional substances, contributing to airway narrowing.

In an asthma attack, the smooth muscles of the bronchi contract, causing the bronchi to narrow (called bronchoconstriction), and the tissues lining the airways swell from inflammation and mucus secretion into the airways. The top layer of the airway lining can become damaged and shed cells, further narrowing the diameter of the airway. A narrower airway requires the person to exert more effort to move air in and out of the lungs. In asthma, the narrowing is reversible, meaning that with appropriate treatment or on their own, the muscular contractions of the airways stop, the airways widen again, and the airflow into and out of the lungs returns to normal.

How Airways Narrow

During an asthma attack, the smooth muscle layer goes into spasm, narrowing the airway. The middle layer swells because of inflammation, and more mucus is produced. In some segments of the airway, mucus forms plugs that nearly or completely block the airway.

In people who have asthma, the airways narrow in response to stimuli that usually do not affect the airways in normal lungs. The narrowing can be triggered by many inhaled allergens, such as pollens, particles from dust mites, body secretions from cockroaches, particles from feathers, and animal dander. These allergens combine with immunoglobulin E (a type of antibody) on the surface of mast cells to trigger the release of asthma-causing chemicals from these cells. (This type of asthma is called allergic asthma.) Although food allergies induce asthma only rarely, certain foods (such as shellfish and peanuts) can induce severe attacks in people who are sensitive to these foods.

Cigarette smoke, cold air, and viral infections can also provoke asthma attacks. Additionally, people who have asthma can develop bronchoconstriction when exercising. Stress and anxiety can trigger mast cells to release histamine and leukotrienes and stimulate the vagus nerve (which connects to the airway smooth muscle), which then contracts and narrows the bronchi. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common trigger of asthma.

Symptoms

Asthma attacks vary in frequency and severity. Some people who have asthma are symptom-free most of the time, with only an occasional, brief, mild episode of shortness of breath. Other people cough and wheeze most of the time and have severe attacks after viral infections, exercise, or exposure to allergens or irritants, including cigarette smoke. Coughing may be the only symptom in some people (cough-variant asthma). Crying or hearty laughing may bring on symptoms in some people. Some people with asthma produce a clear, sometimes sticky (mucoid) phlegm (sputum). Asthma attacks occur most often in the early morning hours when the effects of protective drugs wear off and the body is least able to prevent bronchoconstriction.

An asthma attack may begin suddenly with wheezing, coughing, and shortness of breath. Wheezing is particularly noticeable when the person breathes out. At other times, an asthma attack may come on slowly with gradually worsening symptoms. In either case, people with asthma usually first notice shortness of breath, coughing, or chest tightness. The attack may be over in minutes, or it may last for hours or days. Itching on the chest or neck may be an early symptom, especially in children. A dry cough at night or while exercising may be the only symptom. Symptoms of asthma can also be caused by other disorders. Symptoms are reversible with timely treatment and typically occur after exposure to one or more triggers.

During an asthma attack, shortness of breath may become severe, creating a feeling of severe anxiety. The person instinctively sits upright and leans forward, using the neck and chest muscles to help in breathing, but still struggles for air. Sweating is a common reaction to the effort and anxiety. The pulse usually quickens, and the person may feel a pounding in the chest.

In a very severe asthma attack, a person is able to say only a few words without stopping to take a breath. Wheezing may diminish, however, because hardly any air is moving in and out of the lungs. Confusion, lethargy, and a blue skin color (cyanosis) are signs that the person’s oxygen supply is severely limited, and emergency treatment is needed. Usually, a person recovers completely with appropriate treatment, even from a severe asthma attack. Rarely, some people develop attacks so quickly that they may lose consciousness before they can give themselves effective therapy. Such people should wear a medical alert bracelet and carry a cellular phone to call for emergency medical assistance.

Diagnosis

Doctors suspect asthma based largely on a person’s report of characteristic symptoms. Doctors confirm the diagnosis by doing pulmonary function tests (see page 454). These tests are done before and after giving the person an inhaled drug, called a beta-adrenergic agonist, that reverses bronchoconstriction. If test results are significantly better after the person receives the drug, asthma is thought to be present. If the airways are not narrowed at the time of the test, a diagnosis can be confirmed by doing a challenge test. In a challenge test, pulmonary function is measured before and after the person inhales a chemical (usually methacholine but histamine may be used) that can narrow the airways. The chemical is given in doses that are too low to affect a person with healthy lungs but that cause the airways to narrow in a person with asthma. If the challenge test shows airway narrowing, asthma is thought to be present.

An abbreviated form of pulmonary function testing, spirometry, is used in people known to have asthma. Spirometry can help assess the severity of the airway obstruction and monitor effectiveness of treatment.

Peak expiratory flow (the fastest rate at which air can be exhaled) can be measured using a small handheld peak flow meter. Often, this test is used at home to monitor the severity of asthma. Usually, peak flow rates are lowest between 4 AM and 6 AM and highest at 4 PM. However, more than a 30% difference in rates at these times is considered evidence of moderate to severe asthma.

Determining what triggers a person’s asthma is often difficult. Allergy testing is appropriate when there is a suspicion that some avoidable substance is stimulating attacks (for example, exposure to cat dander). Skin testing can help identify allergens that may trigger asthma symptoms. However, an allergic response to a skin test does not necessarily mean that the allergen being tested is causing the asthma. The person still has to note whether attacks occur after exposure to this allergen. If doctors suspect a particular allergen, a blood test that measures the level of antibody produced in response to the allergen (the radioallergosorbent test [RAST]) can be done to determine the degree of sensitivity.

To test for exercise-induced asthma, an examiner uses spirometry before and after exercise on a treadmill or stationary bicycle to measure how much air the person can exhale in 1 second (forced expiratory volume in 1 second). If the forced expiratory volume in 1 second decreases more than 15%, the person’s asthma can be induced by exercise.

A chest x-ray is not generally helpful in diagnosing asthma. Doctors use chest x-rays when considering another diagnosis. However, a chest x-ray is often obtained when a person with asthma needs to be hospitalized for severe asthma.

Prevention and Treatment

An array of drugs can be used to prevent and treat asthma. Most of the drugs used to prevent asthma are also used to treat an asthma attack but in higher doses or in different forms. Some people need to use more than one drug to prevent and treat their symptoms.

Therapy is based on two classes of drugs: anti-inflammatory drugs and bronchodilators. Anti-inflammatory drugs suppress the inflammation that narrows the airways. Bronchodilators help to relax and widen (dilate) the airways. Anti-inflammatory drugs include corticosteroids (which can be inhaled, taken by mouth, or given intravenously), leukotriene modifiers, and mast cell stabilizers. Bronchodilators include beta-adrenergic agonists (both those for quick relief of symptoms and those for long-term control), drugs with anticholinergic effects, and methylxanthines.

Status Asthmaticus

The most severe form of asthma is called status asthmaticus. In this condition, the lungs are no longer able to provide the body with adequate oxygen or adequately remove carbon dioxide. Without oxygen, many organs begin to malfunction. The buildup of carbon dioxide leads to acidosis, an acidic state of the blood that affects the function of almost every organ. Blood pressure may fall to low levels. The airways are so narrowed that it is difficult to move air in and out of the lungs.

Status asthmaticus requires that an artificial airway be passed through the person’s mouth and throat (intubation) and that a mechanical ventilator be used to assist breathing. Maximum doses of several drugs are also needed. Support is also given to correct acidosis.

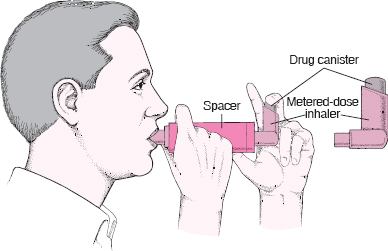

How to Use a Metered-Dose Inhaler

Shake the inhaler after removing the cap.

Shake the inhaler after removing the cap.

Breathe out for 1 or 2 seconds.

Breathe out for 1 or 2 seconds.

Put the inhaler in your mouth or 1 to 2 inches from it and start to breathe in slowly, like sipping hot soup.

Put the inhaler in your mouth or 1 to 2 inches from it and start to breathe in slowly, like sipping hot soup.

While starting to breathe in, press the top of the inhaler.

While starting to breathe in, press the top of the inhaler.

Breathe in slowly until your lungs are full. (This should take about 5 or 6 seconds.)

Breathe in slowly until your lungs are full. (This should take about 5 or 6 seconds.)

Hold your breath for 4 to 6 seconds.

Hold your breath for 4 to 6 seconds.

Breathe out and repeat the procedure.

Breathe out and repeat the procedure.

If this method is difficult, a spacer can be used.

If this method is difficult, a spacer can be used.

Education about how to prevent and treat asthma attacks is beneficial for all people who have asthma and often for their family members. Proper use of inhalers is essential for effective treatment. People should know what can stimulate an attack, what helps to prevent an attack, how to use drugs properly, and when to seek medical care. Many people use a handheld peak flow meter to evaluate their breathing and determine when they need intervention, before their symptoms get extreme. People who experience frequent, severe asthma attacks should know how to reach help quickly.

Many people have a written treatment plan that was devised in collaboration with their doctor. Such a plan allows them to take control of their own treatment and has been shown to decrease the number of times people need to seek care for asthma in the emergency department.

Preventing Attacks

Asthma is a chronic condition that cannot be cured, but individual attacks can often be prevented. Asthma attacks may commonly be prevented if the factors that trigger them are identified and eliminated or avoided. People who have asthma should avoid cigarette smoke. Often, attacks triggered by exercise can be blocked by taking medication beforehand. When dust and allergens are the problem, air filters, air conditioners, and other types of barriers (such as mattress covers, which reduce the amount of particles from dust mites that are in the air) can help considerably. For people whose asthma is stimulated by allergies, desensitization through the use of allergy shots may prevent attacks.

Some people who have asthma may have a sensitivity to aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and must avoid using these drugs. Drugs that block the beneficial effects of beta-adrenergic agonists (called beta-blockers) may worsen asthma.

Most people with asthma take drugs, such as inhaled or oral corticosteroids, leukotriene modifiers, long-acting beta-adrenergic agonists, methylxanthines, antihistamines, or mast cell stabilizers to prevent attacks. Prevention efforts are individualized according to the frequency of attacks and the stimuli that trigger the attacks.

Treating Attacks

An asthma attack can be frightening, both to the person experiencing it and to others around. Even when relatively mild, the symptoms provoke anxiety and alarm. A severe asthma attack is a life-threatening emergency that requires immediate, skilled, professional care. If not treated adequately and quickly, a severe asthma attack can cause death.

People who have asthma are generally able to treat most attacks without assistance from a health care practitioner. Typically, they use an inhaler to deliver a dose of a short-acting beta-adrenergic agonist, move into fresh air (away from cigarette smoke or other irritants), and sit down and rest. An attack usually subsides in 5 to 10 minutes. An attack that does not subside in 15 minutes or that gets worse is likely to require additional treatment supervised by a doctor.

Because people with severe asthma commonly have low blood oxygen levels, doctors may check the level of oxygen by using a sensing monitor on a finger or ear. Supplemental oxygen may be given during attacks. However, in severe attacks, doctors also need to monitor levels of carbon dioxide in the blood, and this test requires a sample of blood from an artery (see page 455). Doctors may also check lung function, usually with a spirometer or a peak flow meter. Usually, a chest x-ray is needed only in severe asthma attacks. People experiencing very severe asthma attacks may need to have an artificial airway passed through their mouth and throat (intubation) and be placed on a mechanical ventilator (see page 527).

Generally, people who have severe asthma are admitted to the hospital if their lung function does not improve after they have received an inhaled beta-adrenergic agonist and corticosteroids by mouth or vein. People also are hospitalized if they have a seriously low blood oxygen level or a high blood carbon dioxide level.

Intravenous fluids may be needed if the person is dehydrated. Antibiotics also may be needed if a doctor suspects a lung infection; however, most such infections are due to viruses for which (with a few exceptions) no treatment exists.

Drugs for Preventing or Treating Attacks

Drugs allow most people with asthma to lead relatively normal lives. Most of the drugs used to treat an asthma attack can be used (often in lower doses) to prevent attacks.

Beta-Adrenergic Agonists: Short-acting beta-adrenergic agonists are usually the best drugs for relieving asthma attacks. They also are used to prevent exercise-induced asthma. These drugs are referred to as bronchodilators because they stimulate beta-adrenergic receptors to widen (dilate) the airways. Bronchodilators that act on all beta-adrenergic receptors throughout the body, such as epinephrine, cause side effects such as rapid heartbeat, restlessness, headache, and muscle tremors. Bronchodilators (such as albuterol) that act mainly on beta2-adrenergic receptors, which are found primarily on cells in the lungs, have little effect on other organs and thus cause fewer side effects. Most beta-adrenergic agonists, especially the inhaled ones, act within minutes, but the effects last only 2 to 6 hours.

Long-acting bronchodilators are available, but because they do not begin to act as quickly, they are used for prevention rather than for attacks of asthma. The long-acting beta-adrenergic agonists are not used alone because people using only long-acting bronchodilators have a slightly higher risk of death. Thus, doctors usually give them together with inhaled corticosteroids.

Most often, beta-adrenergic agonists are inhaled using metered-dose inhalers (handheld cartridges containing gas under pressure). The pressure turns the drug into a fine spray containing a measured dose of drug. Inhalation deposits the drug directly in the airways, so that it acts quickly, but the drug may not reach airways that are severely narrowed. For people who have difficulty using a metered-dose inhaler, spacers or holding chambers can be used. These devices increase the amount of drug delivered to the lungs. With any type of inhaler, proper technique is vital. If the device is not used properly, the drug will not reach the airways. A dry powder drug formulation is also available. The powder formulation is easier for some people to use, in part because it requires less coordination with breathing.

Avoiding Common Causes of Asthma Attacks

The most common indoor allergens are house dust mites, feathers, cockroaches, and animal dander. Anything that can be done to reduce exposure to these allergens may reduce the number or severity of asthma attacks. Exposure to house dust mites can be reduced by removing wall-to-wall carpets and using air conditioning to keep the relative humidity low (preferably below 50%) in the summer. Also, special pillow and mattress covers can help reduce exposure to these dust mites. Animals with fur or hair, most commonly cats and dogs, often must be given away to decrease the overall exposure to animal dander.

Irritating fumes such as cigarette smoke should also be avoided. In some people with asthma, aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs trigger attacks. Tartrazine, a yellow coloring used in some drug tablets and food, may also bring on an attack. Sulfites—commonly added to foods as a preservative—may trigger attacks after a susceptible person eats a certain food or drinks beer or red wine.

For outdoor activity in cold weather, people with asthma can wear a ski mask or scarf that covers the nose and mouth to help keep the air being breathed in warm and moist.

Beta-adrenergic agonists can also be delivered directly to the lungs using a nebulizer. A nebulizer uses pressurized air to create a continuous mist of drug that is inhaled without having to coordinate dosing with breathing. Nebulizers are more portable than they were in the past, and some units can even be plugged into a cigarette lighter in a car. Nebulizers and metered-dose inhalers deliver equivalent amounts of drug to the lungs.

Beta-adrenergic agonists can also be taken in liquid or tablet form or injected. However, the oral drugs tend to work slower than the inhaled or injected ones and are more likely to cause side effects. Side effects include abnormal heart rhythms, which may suggest excessive use.

Other bronchodilators may be combined with beta-adrenergic agonists for acute attacks, including nebulized ipratropium. A combination of ipratropium with albuterol in a metered-dose inhaler is also available.

Quick medical attention should be sought when a person who has asthma feels the need to use more of a beta-adrenergic agonist than is recommended. Overusing these drugs can be very dangerous. The need for continuous use indicates severe broncho-constriction, which can lead to respiratory failure and death.

Methylxanthines: Theophylline, a methylxanthine, is another drug that produces bronchodilation. It is now used less frequently than in the past. Theophyl-line is usually taken by mouth but can be given intravenously in the hospital. Oral theophylline comes in many forms, from short-acting tablets and syrups to longer-acting sustained release capsules and tablets. Theophylline is used for both prevention and treatment of asthma.

The amount of theophylline in the blood can be measured in a laboratory and must be closely monitored by a doctor. Too little drug in the blood may provide little benefit, and too much drug may cause life-threatening abnormal heart rhythms or seizures. When first taking theophylline, a person who has asthma may feel slightly jittery and may develop headaches. These side effects usually disappear as the body adjusts to the drug. Larger doses may cause a rapid heartbeat, nausea, or palpitations. A person may also experience insomnia, agitation, vomiting, and seizures.

Drugs With Anticholinergic Effects: Drugs with anticholinergic effects, such as ipratropium, block acetylcholine from causing smooth muscle contraction and from producing excess mucus in the bronchi. These drugs are usually inhaled but can be given intravenously in the hospital. These drugs further widen (dilate) the airways in people who have already been given beta-adrenergic agonists. However, doctors use drugs with anticholinergic effects mainly in the emergency department in combination with a beta-adrenergic agonist.

Leukotriene Modifiers: Leukotriene modifiers, such as montelukast, zafirlukast, and zileuton also help control asthma. They are anti-inflammatory drugs, preventing the action or synthesis of leukotrienes, chemicals made by the body that cause bronchoconstriction. These drugs, which are taken by mouth, are used more to prevent asthma attacks than to treat them, although because leukotrienes are increased in acute asthma, these drugs potentially can be used during an attack as well.

Mast Cell Stabilizers: These drugs, which are inhaled, include cromolyn and nedocromil. Mast cell stabilizers are thought to inhibit the release of inflammatory chemicals from mast cells and make the airways less likely to narrow. Thus, they are also anti-inflammatory drugs. They are useful for preventing but not treating an attack. These drugs may be helpful for children who have asthma and for people who develop asthma from exercise. Mast cell stabilizers are very safe and must be taken regularly even when a person is free of symptoms.

Corticosteroids: These drugs block the body’s inflammatory response and are exceptionally effective at reducing asthma symptoms. They are the most potent form of anti-inflammatory drugs and have been an important part of asthma treatment for decades. They are given in the inhaled form to prevent attacks and improve lung function. They are given by mouth in higher doses for people experiencing severe attacks. Corticosteroids given by mouth are generally continued for at least several days after a severe attack. Corticosteroids can be taken in several different forms. Often, inhaled versions are best because they deliver the drug directly to the airways and minimize the amount sent throughout the body. They come in several strengths and are generally used twice a day. People should rinse their mouth after use to decrease the likelihood that a fungal infection of the mouth (thrush) develops. Oral or injected corticosteroids may be used in high doses to relieve a severe asthma attack and are generally continued for 1 to 2 weeks. Oral corticosteroids are prescribed on a long-term basis only when no other treatments can control the symptoms.

DRUGS USED TO TREAT ASTHMA

DRUGS USED TO TREAT ASTHMA

| DRUG | SOME SIDE EFFECTS | COMMENTS |

| Short-acting beta-adrenergic agonists | ||

| Albuterol Levalbuterol Pirbuterol |

Increased heart rate Shakiness |

For immediate relief of acute attack |

| Long-acting beta-adrenergic agonists | ||

| Formoterol Salmeterol |

Increased heart rate Shakiness |

For ongoing treatment, not for acute relief Not recommended for use alone (without other asthma drugs) |

| Methylxanthines | ||

| Theophylline | Increased heart rate Shakiness Stomach upset Seizures (if the blood level is high) Serious heartbeat irregularities (if the blood level is high) |

Can be used for prevention and treatment Taken by mouth but can be given intravenously in a hospital |

| Drugs with anticholinergic effects | ||

| Ipratropium | Dry mouth Rapid heart rate |

Used mainly in the emergency department in combination with a beta-adrenergic agonist |

| Mast cell stabilizers | ||

| Cromolyn Nedocromil |

Coughing or wheezing | Useful for preventing attacks, often related to exercise, but not for treatment of an acute attack |

| Corticosteroids (inhaled) | ||

| Beclomethasone Budesonide Flunisolide Fluticasone Mometasone Triamcinolone |

Fungal infection of the mouth (thrush) A change in the voice |

Inhaled for prevention (long-term control) of asthma |

| Corticosteroids (oral) | ||

| Methylprednisolone Prednisolone Prednisone |

Weight gain Elevated blood sugar levels Rarely, psychosis |

Used for acute attacks and for asthma that cannot be controlled with inhaled therapy |

| Leukotriene modifiers | ||

| Montelukast Zafirlukast Zileuton |

Churg-Strauss syndrome With zileuton, elevated liver enzymes |

Used more for prevention (long-term control) than for treatment |

| Immunomodulator | ||

| Omalizumab | Discomfort at the injection site Rarely, anaphylactic reactions |

Used in people with severe asthma to decrease use of oral corticosteroids |

If taken for long periods, corticosteroids gradually reduce the likelihood of an asthma attack by making the airways less sensitive to a number of provocative stimuli. Long-term use of corticosteroids, especially larger doses taken by mouth, can produce side effects including obesity, osteoporosis, elevated blood sugar levels, and, very rarely, psychosis.

Immunomodulators: Omalizumab is a drug that is an antibody. This antibody is directed against a group of other antibodies called immunoglobulin E (IgE). Omalizumab is used in people with asthma who also have severe allergies and high levels of IgE in their blood. Omalizumab prevents IgE from binding to mast cells and thus prevents the release of inflammatory chemicals that can narrow the airways. It can decrease requirements for oral corticosteroids and help relieve symptoms. The drug is injected subcutaneously every 2 weeks.