CHAPTER 85

Pleural Disorders

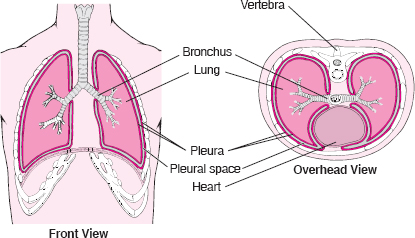

The pleura is a thin, transparent, two-layered membrane that covers the lungs and also lines the inside of the chest wall. The layer that covers the lungs lies in close contact with the layer that lines the chest wall. Between the two thin flexible layers is a small amount of fluid that lubricates them as they slide smoothly over one another with each breath.

In abnormal circumstances, air or excess fluid can get between the pleural surfaces, creating a space. If excess fluid accumulates (called pleural effusion) or if air accumulates (called pneumothorax), one or both lungs may not be able to expand normally with breathing, resulting in the collapse of lung tissue.

Pleural Effusion

Pleural effusion is the abnormal accumulation of fluid in the pleural space.

Fluid can accumulate in the pleural space as a result of a large number of disorders, including infections, injuries, heart or liver failure, blood clots in the lung blood vessels (pulmonary emboli), and drugs.

Fluid can accumulate in the pleural space as a result of a large number of disorders, including infections, injuries, heart or liver failure, blood clots in the lung blood vessels (pulmonary emboli), and drugs.

Symptoms may include difficulty breathing and chest pain, particularly when breathing and coughing.

Symptoms may include difficulty breathing and chest pain, particularly when breathing and coughing.

Diagnosis is by chest x-rays, laboratory testing of the fluid, and often computed tomography.

Diagnosis is by chest x-rays, laboratory testing of the fluid, and often computed tomography.

Large amounts of fluid are drained with a tube inserted into the chest.

Large amounts of fluid are drained with a tube inserted into the chest.

Normally, only a thin layer of fluid separates the two layers of the pleura. An excessive amount of fluid may accumulate for many reasons, including heart failure, cirrhosis, pneumonia, and cancer.

Types of Fluid: Depending on the cause, the fluid may be either rich in protein (exudate) or watery (transudate). Doctors use this distinction to help determine the cause.

Blood in the pleural space (hemothorax) usually results from a chest injury. Rarely, a blood vessel ruptures into the pleural space when no injury has occurred, or a bulging area in the aorta (aortic aneurysm) leaks blood into the pleural space.

Pus in the pleural space (empyema) can accumulate when pneumonia or a lung abscess spreads into the space. Empyema may also complicate an infection from chest wounds, chest surgery, rupture of the esophagus, or an abscess in the abdomen.

Lymphatic (milky) fluid in the pleural space (chylothorax) is caused by an injury to the main lymphatic duct in the chest (thoracic duct) or by a blockage of the duct by a tumor.

Fluid in the pleural space that contains excessive amounts of cholesterol results from a long-standing pleural effusion caused by a condition such as tuberculosis or rheumatoid arthritis.

Symptoms

Many people with pleural effusion have no symptoms at all. The most common symptoms, regardless of the type of fluid in the pleural space or its cause, are shortness of breath and chest pain. Chest pain is usually of a type called pleuritic pain. It may be felt only when the person breathes deeply or coughs, or it may be felt continuously but may be worsened by deep breathing and coughing. The pain is usually felt in the chest wall right over the site of the inflammation. However, the pain may be felt also or only in the upper abdominal region or neck and shoulder as referred pain (see box on page 639). Pleuritic pain is also called pleurisy. Pleurisy can be caused by disorders other than pleural effusion.

Pleuritic chest pain due to a pleural effusion may disappear as fluid accumulates. Large amounts of fluid can cause difficulty in expanding one or both lungs when breathing, causing shortness of breath.

Two Views of the Pleura

Diagnosis

A chest x-ray, which shows fluid in the pleural space, is usually the first step in making the diagnosis. However, small amounts of fluid may not be visible on a chest x-ray. Computed tomography (CT) more clearly shows the lung and the fluid and may show evidence of pneumonia, a pulmonary embolus, a lung abscess, or a tumor. An ultrasound examination may help doctors determine the position of a small accumulation of fluid.

A specimen of the fluid is almost always removed for examination using a needle, a procedure called thoracentesis (see page 456). The appearance of the fluid may help doctors determine its cause. Certain laboratory tests evaluate the chemical composition of the fluid and determine the presence of bacteria, including the bacteria that cause tuberculosis. The fluid specimen is also examined for the number and types of cells and for the presence of cancerous cells.

If these tests cannot identify the cause of the pleural effusion, other tests may be done. Sometimes a sample is obtained using a thoracoscope (a viewing tube that allows doctors to examine the pleural space and obtain tissue samples of the covering of the chest wall or the lung—see page 457). This procedure is called thoracoscopy and can detect cancer and tuberculosis. If thoracoscopy is unavailable, a needle biopsy of the pleura may be done (see page 456). Occasionally, bronchoscopy (a direct visual examination of the airways through a viewing tube) helps doctors find the cause of the fluid. In about 20% of people with pleural effusion, the cause is not obvious after initial testing, and in some people a cause is never found, even after extensive testing.

Common Causes of Pleural Effusion*

Heart failure

Heart failure

Tumors

Tumors

Pneumonia

Pneumonia

Pulmonary embolus

Pulmonary embolus

Surgery, such as recent coronary artery bypass surgery

Surgery, such as recent coronary artery bypass surgery

Injury to the chest

Injury to the chest

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis

Kidney failure

Kidney failure

Systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus)

Systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus)

Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Nephrotic syndrome (protein in the urine and high blood pressure)

Nephrotic syndrome (protein in the urine and high blood pressure)

Peritoneal dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis

Drugs such as hydralazine, procainamide, isoniazid, phenytoin, chlorpromazine, methysergide, interleukin-2, nitrofurantoin, bromocriptine, dantrolene, and procarbazine

Drugs such as hydralazine, procainamide, isoniazid, phenytoin, chlorpromazine, methysergide, interleukin-2, nitrofurantoin, bromocriptine, dantrolene, and procarbazine

*Listed as most common to least common.

Major Causes of Pleurisy

Cancer

Cancer

Drug reactions

Drug reactions

Infection with parasites, such as amebas or flukes

Infection with parasites, such as amebas or flukes

Injury, such as a rib fracture or bruise

Injury, such as a rib fracture or bruise

Irritants that reach the pleura from the airways or elsewhere, such as asbestos

Irritants that reach the pleura from the airways or elsewhere, such as asbestos

Lung infarction caused by pulmonary embolism

Lung infarction caused by pulmonary embolism

Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis

Pneumonia

Pneumonia

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Viral pleuritis

Viral pleuritis

Treatment

Small pleural effusions may not require treatment, although the underlying disorder must be treated. Larger pleural effusions, especially those that cause shortness of breath, may require drainage of the fluid. Usually, drainage dramatically relieves shortness of breath. Often, fluid can be drained using thoracentesis. An area of skin between two lower ribs is anesthetized, then a small needle is inserted and gently pushed deeper until it reaches the fluid. A thin plastic catheter is often guided over the needle into the fluid to lessen the chance of puncturing the lung and causing a pneumothorax. Although thoracentesis is usually done for diagnostic purposes, doctors can safely remove as much as about 1 1/2 quarts (1.5 liters) of fluid at a time using this procedure.

When larger amounts of fluid must be removed, a tube (chest tube) may be inserted through the chest wall. After numbing the area by injecting a local anesthetic, doctors insert a plastic tube into the chest between two ribs. Then doctors connect the tube to a water-sealed drainage system that prevents air from leaking into the pleural space. A chest x-ray is taken to check the tube’s position. Drainage can be blocked if the chest tube is incorrectly positioned or becomes kinked. If the fluid is very thick or full of clots, it may not flow out.

Effusions Caused by Pneumonia: An accumulation of fluid from pneumonia requires intravenous antibiotics and sampling of the fluid. If the fluid is pus or if the fluid has certain characteristics, the fluid needs to be drained, usually with a chest tube. If the fluid has formed within scars (fibrous compartments) in the pleural space, drainage is more difficult. Sometimes drugs called thrombolytics (fibrinolytics) are instilled into the pleural space to help drainage, which may avoid the need for surgery. If surgery is needed, it can be done by using a procedure called video-assisted thoracoscopic debridement or by thoracotomy. During surgery, any thick peels of fibrous material over the lung surface are removed to allow the lung to expand normally.

Effusions Caused by Cancers: Fluid accumulation caused by cancers of the pleura may be difficult to treat because fluid often reaccumulates rapidly. Draining the fluid and giving antitumor drugs sometimes prevents further fluid accumulation. A small tube can be left in the chest so that the fluid can be drained periodically into vacuum bottles. But if fluid continues to accumulate, sealing the pleural space (pleurodesis) may be helpful. For pleurodesis all fluid is drained through a tube, which is then used to administer a pleural irritant, such as a doxycycline solution, bleomycin, or a talc mixture, into the space. The irritant seals the two layers of pleura together, so that no room remains for additional fluid to accumulate. Pleurodesis can also be done using thoracoscopy.

Chylothorax: Treatment of chylothorax focuses on eliminating the leakage from the lymphatic duct. Such treatment may consist of surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation treatment for a cancer that is blocking lymph flow.

Pneumothorax

A pneumothorax is the presence of air between the two layers of pleura, resulting in partial or complete collapse of the lung.

Symptoms include difficulty breathing and chest pain.

Symptoms include difficulty breathing and chest pain.

Diagnosis is by chest x-ray.

Diagnosis is by chest x-ray.

Treatment is usually draining the air with a tube or sometimes a plastic catheter inserted into the chest.

Treatment is usually draining the air with a tube or sometimes a plastic catheter inserted into the chest.

Normally, the pressure in the pleural space is lower than that inside the lungs or outside the chest. If a perforation develops that causes a connection between the pleural space and the inside of the lungs or outside the chest, air enters the pleural space until the pressures become equal or the connection closes. When there is air in the pleural space, the lung partially collapses. Sometimes most or all of the lung collapses, leading to severe shortness of breath.

A pneumothorax that occurs without any apparent cause in people without a known lung disorder is called a primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax usually occurs when a small weakened area of lung (bulla) ruptures. The condition is most common in tall men younger than age 40 who smoke. Most people recover fully; however, primary spontaneous pneumothorax recurs in up to 50% of people.

Spontaneous pneumothorax also occurs in people with an underlying lung disorder (secondary spontaneous pneumothorax). This type of pneumothorax most often results from the rupture of a bulla in older people who have emphysema, but it also occurs in people with other lung conditions, such as cystic fibrosis, asthma, Langerhans’ cell granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, lung abscess, tuberculosis, and Pneumocystis pneumonia. Because of the underlying lung disorder, the symptoms and outcome are generally worse in secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. The recurrence rate is similar to that of primary spontaneous pneumothorax.

A pneumothorax may also occur after an injury or a medical procedure that introduces air into the pleural space, such as thoracentesis, bronchoscopy, or thoracoscopy. Ventilators can cause pressure damage to the lungs (barotrauma) that leads to a pneumothorax— most often in people with emphysema or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (see page 525). Changes in lung pressure (as occur in divers and airline pilots), can increase the risk of pneumothorax.

Symptoms

Symptoms vary greatly depending on how much air enters the pleural space, how much of the lung collapses, and the person’s lung function before the pneumothorax occurred. They range from a little shortness of breath or chest pain to severe shortness of breath, shock, and life-threatening cardiac arrest. Most often, sharp chest pain and shortness of breath and occasionally a dry hacking cough begin suddenly. Pain may also be felt in the shoulder, neck, or abdomen. Symptoms tend to be less severe in a slowly developing pneumothorax than in a rapidly developing one. Except with a very large pneumothorax or a tension pneumothorax, symptoms usually subside as the body adapts to the lung collapse, and the lung slowly begins to reinflate as the air is reabsorbed from the pleural space.

Diagnosis

A physical examination can usually confirm the diagnosis if the pneumothorax is large. Using a stethoscope, a doctor may note that one part of the chest does not transmit the normal sounds of breathing, while tapping (percussing) the chest produces a hollow, drumlike sound. A chest x-ray shows the air pocket and the collapsed lung outlined by the thin inner pleural layer. A chest x-ray can also show if the trachea (the large airway that passes through the front of the neck) is being pushed to one side.

Treatment

A small primary spontaneous pneumothorax usually requires no treatment. It usually does not cause serious breathing problems, and the air is absorbed in several days. The full absorption of air in a larger pneumothorax may take 2 to 4 weeks. However, the air can be removed more quickly by inserting a catheter or chest tube into the pneumothorax.

What Is Tension Pneumothorax?

Tension pneumothorax is a serious and potentially life-threatening form of pneumothorax. In this condition, the tissues surrounding the area where air is entering the pleural space act as a one-way valve, allowing air to enter but not to exit. This situation causes such high pressure in the pleural cavity that the lung completely collapses, and the heart and other structures in the chest cavity are pushed over to the opposite side of the chest.

If not relieved, tension pneumothorax can cause death in minutes. A doctor immediately inserts a needle into the chest to relieve the pressure. Then, a chest tube is inserted separately to drain the air continuously.

If a primary spontaneous pneumothorax is large enough to impair breathing, the air can be removed (aspirated) with a large syringe attached to a plastic catheter inserted into the chest. The catheter can be sealed and then left in place for a time so that any air that reaccumulates can be removed. If catheter aspiration is unsuccessful and for any other type of pneumothorax (such as a secondary spontaneous pneumothorax or a traumatic pneumothorax), a chest tube is used to drain the air. The chest tube is inserted through an incision in the chest wall and is connected to a water-sealed drainage system or a one-way valve that allows the air to exit without allowing any air to get back in. A suction pump may be attached to the chest tube if air keeps leaking in from an abnormal connection (fistula) between an airway and the pleural space. Occasionally, surgery is necessary. Often the surgery is done by using a thoracoscope inserted through the chest wall and into the pleural space.

A recurring pneumothorax can cause considerable disability. Surgery can be done to prevent pneumothorax from recurring. Usually surgery involves repairing leaking areas of the lung and firmly attaching the inner layer of pleura to the outer layer. This surgery is usually done by using a thoracoscope (a tube that allows doctors to view the pleural space—see page 457. People who may need the surgery include

People at high risk—for example, divers and airplane pilots—after the first episode of pneumothorax

People at high risk—for example, divers and airplane pilots—after the first episode of pneumothorax

People who have secondary spontaneous pneumothorax—after the first episode of pneumothorax, if the person is healthy enough to undergo surgery

People who have secondary spontaneous pneumothorax—after the first episode of pneumothorax, if the person is healthy enough to undergo surgery

People who have a pneumothorax that will not heal or a pneumothorax that has occurred twice on the same side

People who have a pneumothorax that will not heal or a pneumothorax that has occurred twice on the same side

If a person with recurring pneumothorax cannot tolerate surgery because of poor health, the pleural space can be sealed by administering a talc mixture or the drug doxycycline through a chest tube that is draining air from the space. However, sealing the space this way is less effective than surgery. When sealed this way, pneumothorax eventually develops again in 25% of people. In contrast, when surgery is done, pneumothorax develops again in only 5% of people.

Viral Pleuritis

Viral pleuritis is a viral infection of the pleurae, which typically causes chest pain when breathing or coughing.

Viral pleuritis is most commonly caused by infection with coxsackie B virus. Occasionally, echovirus causes a rare condition known as epidemic or Bornholm’s pleurodynia. It occurs in the late summer and affects adolescents and young adults.

The primary symptom of viral pleuritis is chest pain. The pain is usually worse when breathing in or coughing and is often sharp. Epidemic or Bornholm’s pleurodynia also causes fever and chest muscle spasms. Chest x-ray is usually done. Viral pleuritis resolves on its own after a few days or more. Analgesics can help relieve the pain.