CHAPTER 88

Cancer of the Lungs

Cigarette smoking is the most common cause of lung cancer.

Cigarette smoking is the most common cause of lung cancer.

One common presenting symptom is a persistent cough.

One common presenting symptom is a persistent cough.

Chest x-rays can detect most lung cancers, but other additional imaging tests and biopsies are needed.

Chest x-rays can detect most lung cancers, but other additional imaging tests and biopsies are needed.

Surgery, chemotherapy, targeted agents, and radiation therapy may all be used to treat lung cancer.

Surgery, chemotherapy, targeted agents, and radiation therapy may all be used to treat lung cancer.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in both men and women. It occurs most commonly between the ages of 45 and 70 and has become more prevalent in women in the last few decades because more women are smoking cigarettes.

Cancer that originates from lung cells is called a primary lung cancer. Primary lung cancer can start in the airways that branch off the trachea to supply the lungs (the bronchi) or in the small air sacs of the lung (the alveoli). Cancer may also spread (metasta-size) to the lung from other parts of the body (most commonly from the breasts, colon, prostate, kidneys, thyroid gland, stomach, cervix, rectum, testes, bone, or skin).

There are two main categories of lung cancer.

Non–small cell lung carcinoma: About 85 to 87% of lung cancers are in this category. This cancer grows more slowly than small cell lung carcinoma. Nevertheless, by the time about 40% of people are diagnosed, the cancer has spread to other parts of the body outside of the chest. The most common types of non–small cell lung carcinoma are squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and large cell carcinoma.

Non–small cell lung carcinoma: About 85 to 87% of lung cancers are in this category. This cancer grows more slowly than small cell lung carcinoma. Nevertheless, by the time about 40% of people are diagnosed, the cancer has spread to other parts of the body outside of the chest. The most common types of non–small cell lung carcinoma are squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and large cell carcinoma.

Small cell lung carcinoma: Also called oat cell carcinoma, this cancer accounts for about 13 to 15% of all lung cancers. It is very aggressive and spreads quickly. By the time that most people are diagnosed, the cancer has metastasized to other parts of the body.

Small cell lung carcinoma: Also called oat cell carcinoma, this cancer accounts for about 13 to 15% of all lung cancers. It is very aggressive and spreads quickly. By the time that most people are diagnosed, the cancer has metastasized to other parts of the body.

Causes

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of cancer, accounting for about 85% of all lung cancer cases. About 10% of all smokers (former or current) eventually develop lung cancer, and both the number of cigarettes smoked and number of years of smoking seem to correlate with the increased risk. In people who quit smoking, the risk of developing lung cancer decreases, but former smokers will still always have a higher risk of developing lung cancer than people who never smoked.

About 15% of people who develop lung cancer have never smoked. In these people, the reason why they develop lung cancer is unknown. Recent studies have found that some people with lung cancer who have never smoked have genetic mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene. Although an environmental association has not clearly been established, it is believed that exposure to radon gas in the home may be a risk factor. Other possible risk factors include exposure to secondhand smoke and exposure to carcinogens such as asbestos, radiation, arsenic, chromates, nickel, chloromethyl ethers, mustard gas, or coke-oven emissions, encountered or breathed in at work. It is believed that the risk of contracting lung cancer is greater in people who are exposed to these substances and who also smoke cigarettes. Air pollution and cigar smoke also contain carcinogens, and exposure to these substances is associated with an increased risk of cancer. In rare incidences, lung cancers, especially adenocarcinoma and bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma (a type of adenocarcinoma), develop in people whose lungs have been scarred by other lung disorders, such as tuberculosis.

Symptoms

The symptoms of lung cancer depend on its type, its location, and the way it spreads. One of the more common symptoms is a persistent cough or, in people who have a chronic cough, a change in the character of the cough. Some people cough up blood or sputum streaked with blood (hemoptysis—see page 452). Rarely, lung cancer grows into an underlying blood vessel and causes severe bleeding. Additional nonspecific symptoms of lung cancer include loss of appetite, weight loss, fatigue, chest pain, and weakness.

Complications: Lung cancer may cause wheezing by narrowing the airway. Blockage of an airway by a tumor may lead to the collapse of the part of the lung that the airway supplies, a condition called atelectasis (see page 495). Other consequences of a blocked airway are shortness of breath and pneumonia, which may result in coughing, fever, and chest pain. If the tumor grows into the chest wall, it may produce persistent, unrelenting chest pain. Fluid containing cancerous cells can accumulate in the space between the lung and the chest wall (pleural effusion—see page 518). Large amounts of fluid can lead to shortness of breath. If the cancer spreads throughout the lungs, the levels of oxygen in the blood drop and become low, causing shortness of breath and eventually enlargement of the right side of the heart and possible heart failure (cor pulmonale—see box on page 523).

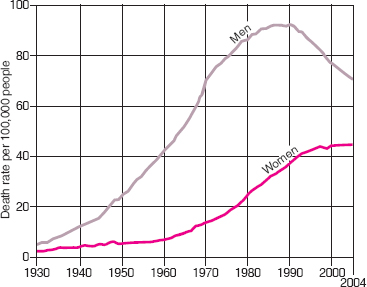

Deaths Due to Lung Cancer

Among cancers, lung cancer is the most common cause of death in men and women. The number of deaths due to lung cancer has been decreasing in men and appears to be leveling off in women after increasing for several decades. These trends reflect a decrease in the number of smokers over the last 30 years. In 2008, more than 162,000 people are expected to have died of lung cancer—about 91,000 men and 71,000 women. This number represents about 28% of all deaths due to cancer.

Lung cancer may grow into certain nerves in the neck, causing a droopy eyelid, small pupil, sunken eye, and reduced perspiration on one side of the face—together these symptoms are called Horner’s syndrome (see page 834). Cancers at the top of the lung may grow into the nerves that supply the arm, making the arm painful, numb, and weak. Tumors in this location are often called Pancoast’s tumors. When the tumor grows into nerves in the center of the chest, the nerve to the voice box may become damaged, making the voice hoarse.

Lung cancer may grow into or near the esophagus, leading to difficulty swallowing or pain with swallowing.

Lung cancer may grow into the heart or in the midchest (mediastinal) region, causing abnormal heart rhythms, blockage of blood flow through the heart, or fluid in the sac surrounding the heart (pericardial sac).

The cancer may grow into or compress one of the large veins in the chest (the superior vena cava); this condition is called superior vena cava syndrome. Obstruction of the superior vena cava causes blood to back up in other veins of the upper body. The veins in the chest wall enlarge. The face, neck, and upper chest wall—including the breasts—can swell, causing pain. The condition can also produce shortness of breath, headache, distorted vision, dizziness, and drowsiness. These symptoms usually worsen when the person bends forward or lies down.

Lung cancer may also spread through the bloodstream to other parts of the body, most commonly the liver, brain, adrenal glands, spinal cord, or bones. The spread of lung cancer may occur early in the course of disease, especially with small cell lung cancer. Symptoms—such as headache, confusion, seizures, and bone pain—may develop before any lung problems become evident, making an early diagnosis more complicated.

Paraneoplastic syndromes (see box on page 1082) consist of effects that are caused by cancer but occur far from the cancer itself, such as in nerves and muscles. These syndromes are not related to the size or location of the lung cancer and do not necessarily indicate that the cancer has spread outside the chest. These syndromes are caused by substances secreted by the cancer (such as hormones, cytokines, and various other proteins).

Uncommon Lung Tumors

Lung tumors can be cancerous or noncancerous. Some less common noncancerous lung tumors include

Hamartomas, which are the most common noncancerous lung tumors

Hamartomas, which are the most common noncancerous lung tumors

Bronchial cystadenomas, which grow in the main or smaller bronchi

Bronchial cystadenomas, which grow in the main or smaller bronchi

Rare cancerous tumors include

Bronchial carcinoid tumors, which may be cancerous or noncancerous

Bronchial carcinoid tumors, which may be cancerous or noncancerous

Lymphomas, which are cancers of the lymphatic system

Lymphomas, which are cancers of the lymphatic system

All lung tumors require medical evaluation because even noncancerous tumors can cause problems if they grow and block breathing. The treatment of lung tumors depends on whether they are cancerous or noncancerous. Some noncancerous tumors may need to be removed surgically to prevent the airway from becoming blocked.

Diagnosis

Doctors explore the possibility of lung cancer when a person, especially a smoker, has a persistent or worsening cough or other lung symptoms (such as shortness of breath or coughed-up sputum tinged with blood). Usually, the first test is a chest x-ray, which can detect most lung tumors, although it may miss small ones. Sometimes a shadow detected on a chest x-ray done for other reasons (such as before surgery) provides doctors with the first clue, although such a shadow is not proof of cancer.

A computed tomography (CT) scan may be done next. CT scans can show characteristic patterns that help doctors make the diagnosis. They also can show small tumors that are not visible on chest x-rays and reveal whether the lymph nodes inside the chest are enlarged. Newer techniques, such as positron emission tomography (PET—see page 456) and a certain type of CT called helical (spiral) CT, are improving the ability to detect small cancers. Oncologists frequently use PET-CT scanners, which combine the PET and CT technology in one machine, to evaluate patients with suspected cancer. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be used if the CT or PET-CT scans do not give doctors sufficient information.

A microscopic examination of lung tissue from the area that may be cancerous is usually needed to confirm the diagnosis. In rare cases, a sample of coughed-up sputum can provide enough material for an examination (called sputum cytology). Almost always, doctors need to obtain a sample of tissue directly from the tumor. One common way to obtain the tissue sample is with bronchoscopy. The person’s airway is directly observed and samples of the tumor can be obtained (see page 456). If the cancer is too far away from the major airways to be reached with a bronchoscope, doctors can usually obtain a specimen by inserting a needle through the skin while using CT for guidance. This procedure is called a needle biopsy (see page 456). Sometimes, a specimen can only be obtained by a surgical procedure called a thoracotomy (see page 458). Doctors may also perform a mediastinoscopy, in which they take and examine samples of enlarged lymph nodes (a biopsy) from the center of the chest to determine if inflammation or cancer is responsible for the enlargement.

Once cancer has been identified under the microscope, doctors usually do tests to determine whether it has spread. A PET-CT scan and head imaging (brain CT or MRI) may be done to determine if lung cancer has spread, especially to the liver, adrenal glands, or brain. If a PET-CT is not available, CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and a bone scan are done. A bone scan may show that cancer has spread to the bones. Because small cell lung cancer can spread to the bone marrow, doctors sometimes also do a bone marrow biopsy.

Cancers are categorized on how large the tumor is, whether it has spread to nearby lymph nodes, and whether it has spread to distant organs. The different categories are used to determine the stage of the cancer (see page 1083). The stage of a cancer suggests the most appropriate treatment and enables doctors to estimate the person’s prognosis.

Screening: Clinical trials are underway to determine the value of screening tests to detect lung cancer in people who do not have any symptoms. These trials use chest x-rays, CT scans, sputum examinations, or all these methods to try to detect cancer when it is at an early stage. However, screening so far has not been shown to improve lung cancer detection, and therefore screening is not recommended for people who have no risk factors and no symptoms. Tests can be expensive and cause people undue worry if they produce false-positive results that incorrectly imply that a cancer is present. The opposite is also true. A screening test can give a negative result when a cancer really does exist. For these reasons, it is important for doctors to try to accurately determine a person’s risk for a particular cancer before screening tests are done (see page 1081).

Prevention and Treatment

Prevention of lung cancer includes quitting smoking (see page 2096) and avoiding exposure to potentially cancer-causing substances in the work environment.

Doctors use various treatments for both small cell and non–small cell lung cancer. Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy can be used individually or in combination. The precise combination of treatments depends on the type, location, and severity of the cancer, whether the cancer has spread, and the person’s overall health. For example, in some people with advanced non–small cell lung cancer, treatment includes chemotherapy and radiation therapy before, after, or instead of surgical removal. Some people with non–small cell lung cancer survive significantly longer when treated with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or some of the newer targeted therapies. Targeted therapies include drugs, such as biologic agents that specifically target lung tumors. Recent studies have identified proteins within cancer cells and the blood vessels that nourish the cancer cells. These proteins may be involved in regulating and promoting cancer growth and metastasis. Drugs have been designed to specifically affect the abnormal protein expression and potentially kill the cancer cells or inhibit their growth. For example, doctors may give epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors to people who have not responded to traditional chemotherapy regimens. Some people may receive vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptor inhibitors in combination with standard chemotherapy regimens.

Laser therapy, in which a laser is used to remove or reduce the size of lung tumors, and photodynamic therapy, in which light is used to shrink tumors, are sometimes used. Radiofrequency ablation, in which an electrical current is used to destroy tumor cells, can sometimes be used in people who have small tumors or are unable to undergo surgery.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Although smoking causes most cases, people who have never smoked may still get lung cancer.

Surgery: Surgery is the treatment of choice for non–small cell lung cancer that has not spread beyond the lung (early-stage disease). In general, surgery is not used for early-stage small cell lung cancer, because this aggressive cancer requires chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Surgery may not be possible if the cancer has spread beyond the lungs, if the cancer is too close to the windpipe, or if the person has other serious conditions (such as severe heart or lung disease).

Before surgery, doctors do pulmonary function tests (see page 454) to determine whether the amount of lung remaining after surgery will be able to provide enough oxygen and breathing function. If the test results indicate that removing the cancerous part of the lung will result in inadequate lung function, surgery is not possible. The amount of lung to be removed is decided by the surgeon, with the amount varying from a small part of a lung segment to an entire lung.

Although non–small cell lung cancers can be removed surgically, removal does not always result in a cure. Supplemental (adjuvant) chemotherapy after surgery can help increase the survival rate.

Occasionally, cancer that begins elsewhere (for example, in the colon) and spreads to the lungs is removed from the lungs after being removed at the source. This procedure is recommended rarely, and tests must show that the cancer has not spread to any site outside of the lungs.

Radiation Therapy: Radiation therapy is used in both non-small cell and small cell lung cancers. It may be given to people who do not want to undergo surgery, who cannot undergo surgery because they have another condition (such as severe coronary artery disease), or whose cancer has spread to nearby structures, such as the lymph nodes. Although radiation therapy is used to treat the cancer, in some people, it may only partially shrink the cancer or slow its growth. Combining chemotherapy with radiation therapy improves survival in this group. People with limited or extensive-stage small cell lung cancer who have been responding well to chemotherapy may benefit from radiation therapy to the head to prevent spread of cancer to the brain. If the cancer has already spread to the brain, radiation therapy of the brain is commonly used to reduce symptoms such as headache, confusion, and seizures. Radiation therapy is also useful for controlling the complications of lung cancer, such as coughing up of blood, bone pain, superior vena cava syndrome, and spinal cord compression.

Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy is used in both non-small cell and small cell lung cancers. In small cell lung cancer, chemotherapy, sometimes coupled with radiation therapy, is the main treatment. This approach is preferred because small cell lung cancer is aggressive and has often spread to distant parts of the body by the time of diagnosis. Chemotherapy can prolong survival in people who have extensive-stage disease. Without treatment, the median survival is only 6 to 12 weeks.

In non–small cell lung cancer, chemotherapy also prolongs survival and treats symptoms. In people with non–small cell lung cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, the median survival increases to 9 months with treatment. Targeted therapies may also improve cancer patient survival.

Other Treatments: Other treatments are often needed for people who have lung cancer. Because many people who have lung cancer have a substantial decrease in lung function whether or not they undergo treatment, oxygen therapy (see page 460) and bronchodilators (drugs that widen the airways) may aid breathing. Many people with advanced lung cancer develop such extreme pain and difficulty in breathing that they require large doses of opioids in the weeks or months before their death. Fortunately, opioids can substantially relieve pain if adequate doses are used.

Prognosis

Lung cancer has a poor prognosis. On average, people with untreated advanced non–small cell lung cancer survive 6 months. Even with treatment, people with extensive small cell lung cancer or advanced non–small cell lung cancer do especially poorly, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 1%. Early diagnosis improves survival. People with early non–small cell lung cancer have a 5-year survival of 60 to 70%. However, people who are treated definitively for an earlier stage lung cancer and survive but continue to smoke are at high risk of developing another lung cancer.

Survivors must have regular checkups, including periodic chest x-rays and CT scans to ensure that the cancer has not returned. Usually, if the cancer returns, it occurs within the first 2 years. However, frequent monitoring is recommended for 5 years after lung cancer treatment, and then people are monitored yearly for the rest of their lives.

Because many people die of lung cancer, planning for terminal care is usually necessary. Advances in end-of-life care, particularly the recognition that anxiety and pain are common in people with incurable lung cancer and that these symptoms can be relieved by appropriate drugs, have led to an increasing number of people being able to die comfortably at home, with or without hospice services (see page 61).