CHAPTER 96

Joint Disorders

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (sometimes called degenerative arthritis, degenerative joint disease, osteoarthrosis, or hypertrophic osteoarthritis) is a chronic disorder associated with damage to the cartilage and surrounding tissues and characterized by pain, stiffness, and loss of function.

Arthritis due to damage of joint cartilage and surrounding tissues becomes very common with aging.

Arthritis due to damage of joint cartilage and surrounding tissues becomes very common with aging.

Pain, swelling, and bony overgrowth are common, as well as stiffness that follows awakening or inactivity and disappears within 30 minutes, particularly if the joint is moved.

Pain, swelling, and bony overgrowth are common, as well as stiffness that follows awakening or inactivity and disappears within 30 minutes, particularly if the joint is moved.

The diagnosis is based on symptoms and x-rays.

The diagnosis is based on symptoms and x-rays.

Treatment includes exercises and other physical measures, drugs that reduce pain and improve function, and, for very severe changes, joint replacement or other surgery.

Treatment includes exercises and other physical measures, drugs that reduce pain and improve function, and, for very severe changes, joint replacement or other surgery.

Osteoarthritis, the most common joint disorder, often begins in the 40s and 50s and affects almost all people to some degree by age 80. Before the age of 40, men develop osteoarthritis more often than do women, often because of injury. From age 40 to 70, women develop the disorder more often than do men. After age 70, the disorder develops in both sexes equally.

Causes

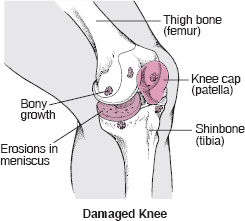

Normally, joints have such a low friction level that they are protected from wearing out, even after years of use. Osteoarthritis is caused most often by tissue damage. In an attempt to repair a damaged joint, chemicals accumulate in the joint and increase the production of the components of cartilage, such as collagen (a tough, fibrous protein in connective tissue) and proteoglycans (substances that provide resilience). Next, the cartilage may swell because of water retention, become soft, and then develop cracks on the surface. Tiny cavities form in the bone beneath the cartilage, weakening the bone. The attempt of the tissues to repair the damage may lead to new growth of cartilage, bone, and other tissue. Bone can overgrow at the edges of the joint, causing bumps (osteophytes) that can be seen and felt. Ultimately, the smooth, slippery surface of the cartilage becomes rough and pitted, so that the joint can no longer move smoothly and absorb impact. All the components of the joint—bone, joint capsule (tissues that enclose most joints), synovial tissue (tissue lining the joint cavity), tendons, ligaments, and cartilage—fail in various ways, thus altering the function of the joint.

SPOTLIGHT ON AGING

Many myths about osteoarthritis persist—for example, that it is an inevitable part of aging, like gray hair and skin changes, that it results in little disability, and that treatment is not effective.

Many myths about osteoarthritis persist—for example, that it is an inevitable part of aging, like gray hair and skin changes, that it results in little disability, and that treatment is not effective.

Osteoarthritis does become more common with aging. For instance, as people age, the cartilage that lines the joints tends to thin. The surfaces of a joint may not slide over each other as well as they used to, and the joint may be slightly more susceptible to injury. However, osteoarthritis is not an inevitable part of aging. It is not caused simply by the wear and tear that occurs with years of joint use. Other factors may include single or repeated injury, abnormal motion, metabolic disorders, joint infection, or another joint disorder.

Also, osteoarthritis commonly causes disability in later life. Effective treatment, such as analgesics, exercises and physical therapy, and, in some cases, surgery, is available.

Ligament damage is also common with aging. Ligaments, which bind joints together, tend to become less elastic as people age, making joints feel tight or stiff. This change results from chemical changes in the proteins that make up the ligaments. Consequently, most people become less flexible as they age. Ligaments tend to tear more easily, and when they tear, they heal more slowly. Older people should stretch before exercising to decrease the chance of ligament tears. They should also have their exercise regimen reviewed by a trainer or doctor so that exercises likely to tear ligaments can be avoided.

Osteoarthritis is classified as primary (or idiopathic) when the cause is not known (as in the large majority of cases). It is classified as secondary when the cause is another disease or condition, such as an infection, deformity, injury, abnormal use of a joint, metabolic disorder (for example, excess iron in the body [hemochromatosis] or excess copper in the liver [Wilson’s disease]), or a disorder that damages joint cartilage (for example, rheumatoid arthritis or gout). Some people who repetitively stress one joint or a group of joints, such as foundry workers, farmers, coal miners, and bus drivers, are particularly at risk. The major risk factor for osteoarthritis of the knee comes from having an occupation that involves bending of the joint. Curiously, long-distance running does not increase the risk of developing the disorder. However, once osteoarthritis develops, this type of exercise often makes the disorder worse. Obesity may be a major factor in the development of osteoarthritis, particularly of the knee and especially in women.

Symptoms

Usually, symptoms develop gradually and affect only one or a few joints at first. Joints of the fingers, base of the thumbs, neck, lower back, big toes, hips, and knees are commonly affected. Pain, often described as a deep ache, is the first symptom and, when in the weight-bearing joints, is usually made worse by activities that involve weight bearing (such as standing. In some people, the joint may be stiff after sleep or some other inactivity, but the stiffness usually subsides within 30 minutes, particularly if the joint is moved.

As the condition causes more symptoms, the joint may become less movable and eventually may not be able to fully straighten or bend. New growth of cartilage, bone, and other tissue can enlarge the joints. The irregular cartilage surfaces cause joints to grind, grate, or crackle when they are moved. Bony growths commonly develop in the joints closest to the fingertips (called Heberden’s nodes) or middle of the fingers (called Bouchard’s nodes).

In some joints (such as the knee), the ligaments, which surround and support the joint, stretch so that the joint becomes unstable. Alternatively, the hip or knee may become stiff, losing its range of motion. Touching or moving the joint (particularly when standing, climbing stairs, or walking) can be very painful.

Osteoarthritis often affects the spine. Back pain is the most common symptom. Usually, damaged disks or joints in the spine cause only mild pain and stiffness. However, osteoarthritis in the neck or lower back can cause numbness, pain, and weakness in an arm or leg if the overgrowth of bone presses on nerves. The overgrowth of bone may be within the spinal canal in the lower back (lumbar spinal stenosis), pressing on nerves before they exit the canal to go to the legs. This pressure may cause leg pain after walking, suggesting incorrectly that the person has a reduced blood supply to the legs (intermittent claudication—see page 419). Rarely, bony growths compress the esophagus, making swallowing difficult.

How to Live With Osteoarthritis

Exercise affected joints gently (by exercising in a pool if possible, by using a stationary bicycle, or by walking).

Exercise affected joints gently (by exercising in a pool if possible, by using a stationary bicycle, or by walking).

Receive acupuncture or massage at and around affected joints (these measures should preferably be done by a trained therapist).

Receive acupuncture or massage at and around affected joints (these measures should preferably be done by a trained therapist).

Apply a heating pad or a damp and warm towel to affected joints.

Apply a heating pad or a damp and warm towel to affected joints.

Avoid gaining too much weight (so as not to place extra stress on joints), or lose weight if overweight.

Avoid gaining too much weight (so as not to place extra stress on joints), or lose weight if overweight.

Use special equipment as necessary (for example, cane, crutches, walker, neck collar, or elastic knee support to protect joints from overuse; or a fixed seat placed in a bathtub to enable less stretching while washing).

Use special equipment as necessary (for example, cane, crutches, walker, neck collar, or elastic knee support to protect joints from overuse; or a fixed seat placed in a bathtub to enable less stretching while washing).

Wear well-supported shoes or athletic shoes.

Wear well-supported shoes or athletic shoes.

Osteoarthritis may be stable for many years or may progress very rapidly, but most often it progresses slowly after symptoms develop. Many people develop some degree of disability.

Diagnosis

The doctor makes the diagnosis based on the characteristic symptoms, physical examination, and the x-ray appearance of joints (such as bone enlargement and narrowing of the joint space). By age 40, many people have some evidence of osteoarthritis on x-rays, especially in weight-bearing joints such as the hip and knee, but only half of these people have symptoms. However, x-rays are not very useful for detecting osteoarthritis early because they do not show changes in cartilage, which is where the earliest abnormalities occur. Also, changes on the x-ray often correlate poorly with symptoms. For example, an x-ray may show only a minor change in a person who has severe symptoms, or an x-ray may show numerous changes in a person who has very few, if any, symptoms.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can reveal early changes in cartilage, but it is rarely needed for the diagnosis. Also, MRI is in too short supply to justify routine use. There are no blood tests for the diagnosis of osteoarthritis, although blood tests may help rule out other disorders (such as rheumatoid arthritis—see page 563). If a joint is swollen, a sample of the joint fluid is sometimes withdrawn using a needle and local anesthesia. Analysis of the fluid can help differentiate osteoarthritis from disorders such as infection and gout.

Treatment

Appropriate exercises—including stretching, strengthening, and postural exercises—help maintain healthy cartilage, increase a joint’s range of motion, and strengthen surrounding muscles so that they can absorb stress better. Exercise can sometimes stop or even reverse osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Stretching exercises should be performed daily. Exercise must be balanced with rest of painful joints, but immobilizing a joint is more likely to worsen the disease than relieve it. Using excessively soft chairs, recliners, mattresses, and car seats may worsen symptoms. Using car seats moved forward, straight-backed chairs with relatively high seats (such as kitchen or dining room chairs), firm mattresses, and bed boards (available at many lumber yards) and wearing wear well-supported shoes or athletic shoes are often recommended.

For osteoarthritis of the spine, specific exercises sometimes help, and back supports or braces may be needed when pain is severe. Exercises should include both muscle-strengthening as well as low-impact aerobic exercises (such as walking, swimming, and bicycle riding). If possible, people should maintain ordinary daily activities and continue to perform their normal activities, such as a hobby or job. However, physical activities may have to be adjusted to avoid bending and thus aggravating the pain of osteoarthritis.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Acetaminophen is almost always preferred to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for initial treatment of osteoarthritis because it is usually as effective and safer.

Physical therapy, often with heat therapy (see page 46), can be helpful. Range-of-motion exercises performed in warm water are helpful because heat improves muscle function by reducing stiffness and muscle spasm. Cold may be applied to reduce pain from temporary worsening in one joint. Splints or supports (such as a cane, crutch, brace, or even a walker) can protect specific joints during painful activities. Shoe inserts (orthotics) may help reduce pain caused by walking. Massage by trained therapists and deep heat treatment with diathermy or ultrasound may be useful.

Drugs are used to supplement exercise and physical therapy. Drugs, which may be used in combination or individually, do not directly alter the course of osteoarthritis. They are used to reduce symptoms and thus allow more normal daily activities. A simple pain medicine (analgesic), such as acetaminophen, may be all that is needed for mild to moderate pain. Alternatively, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) may be taken to lessen pain and swelling. NSAIDs reduce pain and inflammation in joints (see page 644). However, they have a higher risk of serious side effects than acetaminophen when used long term. Sometimes other types of pain medicine may be needed. For example, a cream derived from cayenne pepper—the active ingredient is capsaicin—can be applied directly to the skin over the joint.

Muscle relaxants (usually in low doses) occasionally relieve pain caused by muscles straining to support joints affected by osteoarthritis. In older people, however, they tend to cause more side effects than relief.

If a joint suddenly becomes inflamed, swollen, and painful, most of the fluid inside the joint may need to be removed and a special form of cortisone may be injected directly into the joint. This treatment may provide only short-term relief, and a joint treated with cortisone should not be used too often or damage may result. A series of 3 to 5 weekly injections of hyaluronate (similar to a component of normal joint fluid) into the joint may provide significant pain relief in some people for prolonged periods of time (up to a year).

Several nutritional supplements (such as glucosamine sulfate and chondroitin sulfate) are being tested for potential benefit in treating osteoarthritis. So far, results are contradictory, and the potential benefit of glucosamine sulfate and chondroitin sulfate is unclear. There is less evidence that other nutritional supplements work.

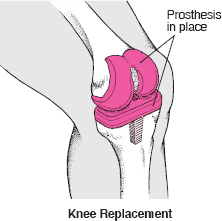

Surgical treatment may help when all other treatments fail to relieve pain or improve function. Some joints, most commonly the hip (see art on page 1961) and knee (see art below), can be replaced with an artificial joint. Replacement is usually very successful, almost always improving motion and function and dramatically decreasing pain. Therefore, joint replacement should be considered when pain is unmanageable and function becomes limited. Because the artificial joint does not last forever, the procedure is often delayed as long as possible in young people so the need for repeated replacements can be minimized.

A variety of methods that restore cells inside cartilage have been used in younger people with osteoarthritis (often caused by an injury) to help heal small defects in cartilage. However, such methods have not yet proved valuable when cartilage defects are extensive, as commonly occurs in older people.

Replacing a Knee

A knee joint damaged by osteoarthritis may be replaced with an artificial joint. After a general anesthetic is given, the surgeon makes an incision over the damaged knee. The knee cap (patella) may be removed, and the ends of the thigh bone (femur) and shinbone (tibia) are smoothed so that the parts of the artificial joint (prosthesis) can be attached more easily. One part of the artificial joint is inserted into the thigh bone, the other part is inserted into the shinbone, and then the parts are cemented in place.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is an inflammatory arthritis in which joints, usually including those of the hands and feet, are inflamed, resulting in swelling, pain, and often destruction of joints.

The immune system damages the joints and connective tissues.

The immune system damages the joints and connective tissues.

Joints (typically the small joints of the limbs) become painful and have stiffness that persists for more than 60 minutes on awakening and after inactivity.

Joints (typically the small joints of the limbs) become painful and have stiffness that persists for more than 60 minutes on awakening and after inactivity.

Fever, weakness, and damage to other organs may occur.

Fever, weakness, and damage to other organs may occur.

Diagnosis is based mainly on symptoms but also on blood tests for rheumatoid factor and on x-rays.

Diagnosis is based mainly on symptoms but also on blood tests for rheumatoid factor and on x-rays.

Treatment can include exercises and splinting, drugs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and immunosuppressive drugs), and surgery.

Treatment can include exercises and splinting, drugs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and immunosuppressive drugs), and surgery.

Worldwide, rheumatoid arthritis develops in about 1% of the population, regardless of race or country of origin, affecting women 2 to 3 times more often than men. Usually, rheumatoid arthritis first appears between 35 years and 50 years of age, but it may occur at any age. A disorder similar to rheumatoid arthritis can occur in children. The disease is then called juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and the symptoms and prognosis are often somewhat different (see page 1829).

The exact cause of rheumatoid arthritis is not known. It is considered an autoimmune disease (see page 1124). Components of the immune system attack the soft tissue that lines the joints and can also attack connective tissue in many other parts of the body, such as the blood vessels and lungs. Eventually, the cartilage, bone, and ligaments of the joint erode, causing deformity, instability, and scarring within the joint. The joints deteriorate at a variable rate. Many factors, including genetic predisposition, may influence the pattern of the disease. Unknown environmental factors (such as viral infections) are thought to play a role.

Symptoms

People with rheumatoid arthritis may have a mild course, occasional flare-ups with long periods of remission (in which the disease is inactive), or a steadily progressive disease, which may be slow or rapid. Rheumatoid arthritis may start suddenly, with many joints becoming inflamed at the same time. More often, it starts subtly, gradually affecting different joints. Usually, the inflammation is symmetric, with joints on both sides of the body affected about equally. Typically, the small joints in the fingers, toes, hands, feet, wrists, elbows, and ankles become inflamed first. The inflamed joints are usually painful and often stiff, especially just after awakening (such stiffness generally lasts for more than 60 minutes) or after prolonged inactivity. Some people feel tired and weak, especially in the early afternoon. Rheumatoid arthritis may cause a loss of appetite with weight loss and a low-grade fever.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

It is rare for specific foods to cause flare-ups of rheumatoid arthritis.

Affected joints are tender, warm, red, and enlarged because of swelling of the soft tissue and sometimes fluid within the joint. Joints can quickly become deformed. Joints may freeze in one position so that they cannot bend or open fully. The fingers may tend to dislocate slightly from their normal position toward the little finger on each hand, causing tendons in the fingers to slip out of place.

Swollen wrists can pinch a nerve and result in numbness or tingling due to carpal tunnel syndrome (see page 601). Cysts, which may develop behind affected knees, can rupture, causing pain and swelling in the lower legs. Up to 30% of people with rheumatoid arthritis have hard bumps (called rheumatoid nodules) just under the skin, usually near sites of pressure (such as the back of the forearm near the elbow).

Rarely, rheumatoid arthritis causes an inflammation of blood vessels (vasculitis—see page 582). This condition reduces the blood supply to tissues and may cause nerve damage or leg sores (ulcers). Inflammation of the membranes that cover the lungs (pleura) or of the sac surrounding the heart (pericardium) or inflammation and scarring of the lungs or heart can lead to chest pain or shortness of breath. Some people develop swollen lymph nodes; Sjögren’s syndrome, which consists of dry eyes, mouth, vagina, or a combination (see page 577); or red, painful eyes caused by inflammation (episcleritis).

Diagnosis

In addition to the important characteristic pattern of symptoms, the doctor may use the following to support the diagnosis: laboratory tests, an examination of a joint fluid sample obtained with a needle, and even a biopsy (removal of a tissue sample for examination under a microscope) of rheumatoid nodules. Characteristic changes in the joints may be seen on x-rays. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) seems to be more sensitive and detects joint abnormalities earlier but is not usually necessary for making the diagnosis.

Blood Tests: In 9 of 10 people who have rheumatoid arthritis, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR—a test that measures the rate at which red blood cells settle to the bottom of a test tube containing blood) is increased, which suggests that active inflammation is present. However, similar increases in the ESR occur in many other disorders. Doctors may monitor the ESR to help determine whether the disease is active.

Many people with rheumatoid arthritis have distinctive antibodies in their blood, such as rheumatoid factor, which is present in 70% of people with rheumatoid arthritis. (Rheumatoid factor also occurs in several other diseases, such as hepatitis and some other infections. Some people even have rheumatoid factor in their blood without any evidence of disease.) Usually, the higher the level of rheumatoid factor in the blood, the more severe the rheumatoid arthritis and the poorer the prognosis. The rheumatoid factor level may decrease when joints are less inflamed.

Anti-citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies are present in 96% of people who have rheumatoid arthritis and are almost always absent in people who do not have rheumatoid arthritis. Doctors are starting to use tests for anti-CCP antibodies to help diagnose rheumatoid arthritis.

Most people have mild anemia (an insufficient number of red blood cells—see page 1031). Rarely, the white blood cell count becomes abnormally low. When a person with rheumatoid arthritis has a low white blood cell count and an enlarged spleen, the disorder is called Felty’s syndrome.

Prognosis

The course of rheumatoid arthritis is unpredictable. The disorder progresses most rapidly during the first 6 years, particularly the first year, and 80% of people develop permanent joint abnormalities within 10 years. Rheumatoid arthritis may decrease life expectancy by 3 to 7 years. Heart disease, infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, drug treatment, cancer, and the underlying disease may be responsible. Rarely, rheumatoid arthritis resolves spontaneously.

Treatment relieves symptoms in 3 of 4 people; however, at least 10% are eventually severely disabled despite full treatment. Factors that tend to predict a poorer prognosis include the following:

Being white, a woman, or both

Being white, a woman, or both

Having rheumatoid nodules

Having rheumatoid nodules

Being older when the disorder begins

Being older when the disorder begins

Having inflammation in 20 or more joints

Having inflammation in 20 or more joints

Having a high ESR

Having a high ESR

Having high levels of rheumatoid factor or anti-CCP

Having high levels of rheumatoid factor or anti-CCP

Treatment

Treatments include simple, conservative measures in addition to drugs and surgical treatments. Simple measures are meant to help the person’s symptoms and include rest and adequate nutrition. Because disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) may actually slow progression of the disease as well as relieve symptoms, they are often started soon after the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis is made.

Severely inflamed joints should be rested, because using them can aggravate the inflammation. Regular rest periods often help relieve pain, and sometimes a short period of bed rest helps relieve a severe flare-up in its most active, painful stage. Splints can be used to immobilize and rest one or several joints, but some systematic movement of the joints is needed to prevent adjacent muscles from weakening and joints from freezing in place.

A regular, healthy diet is generally appropriate. A diet rich in fish and plant oils but low in red meat can have small beneficial effects on the inflammation. Rarely, people have flare-ups after eating certain foods, and if so, these foods should be avoided. Many diets have been proposed but have not proven helpful. Fad diets should be avoided.

The main categories of drugs used to treat rheumatoid arthritis are the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), DMARDs, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive drugs. Newer drugs include leflunomide, anakinra (an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-inhibiting drugs, and other drugs that modify the immune response (immunosuppressive drugs). Generally, stronger drugs have potentially serious side effects that must be looked for during treatment.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: NSAIDs (see page 644) are commonly used to treat the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. They do not prevent the damage caused by rheumatoid arthritis from progressing and thus should not be considered the primary treatment. NSAIDs can reduce the swelling in affected joints and relieve pain. Rheumatoid arthritis, unlike osteoarthritis, causes considerable inflammation. Thus, drugs that decrease inflammation, including NSAIDs, have an important advantage over drugs such as acetaminophen that reduce pain but not inflammation. However, all NSAIDs (including aspirin) cause side effects and can upset the stomach and cannot be taken by anyone who has active digestive tract (peptic) ulcers—including stomach ulcers or duodenal ulcers. Drugs called proton pump inhibitors (such as esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole) can reduce the risk of stomach or duodenal ulcers. Other possible side effects of NSAIDs may include headache, confusion, worsening of high blood pressure, worsening of kidney function, and swelling. People who get hives or asthma after they take aspirin may have the same symptoms after taking other NSAIDs. NSAIDs may increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes. The risk appears to be higher if the drug is used at higher doses and for longer periods of time. The risk is higher with certain NSAIDs than others.

Aspirin is no longer used to treat rheumatoid arthritis because effective doses are often toxic.

The cyclooxygenase (COX-2) inhibitors (coxibs, such as celecoxib) are NSAIDs that act similarly to the other NSAIDs but are less likely to damage the stomach. However, if a person takes aspirin, stomach damage is almost as likely to occur as with other NSAIDs. Caution should be taken with use of coxibs and probably all NSAIDs for long periods or by people with risk factors for heart attack and stroke.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs): DMARDs, such as methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, and sulfasalazine, slow the progression of rheumatoid arthritis and sometimes can improve the course of the disease, although most take weeks or months to have an effect. These drugs are usually added promptly after the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis is made. Even if pain is decreased with NSAIDs, a doctor will likely prescribe a DMARD because the disease progresses even if symptoms are absent or mild.

About 66% of people improve overall, but complete remissions are uncommon. The progression of arthritis usually slows, but pain may remain. People should be made fully aware of the risks of DMARDs and monitored carefully for evidence of toxicity.

Combinations of DMARDs may be more effective than single drugs. For example, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, and methotrexate together are more effective than methotrexate alone or the other two together. Also, combining certain immunosuppressant drugs with a DMARD is often more effective than using a single drug or certain combinations of DMARDs. For example, methotrexate can be combined with a TNF inhibitor.

Methotrexate is taken by mouth once weekly. It is anti-inflammatory at the low doses used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. It is very effective and begins to work within a few weeks, which is relatively rapid for a DMARD. If a person has liver dysfunction or diabetes and takes methotrexate, frequent doctor visits and blood tests may be warranted so that possible side effects can be detected early. The liver can scar, but this most often can be detected and reversed before major damage develops. People must refrain from drinking alcohol to minimize the risk of liver damage. Bone marrow suppression (suppression of the production of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets) is possible. Blood counts should be tested about every 2 months in all people taking the drug. Inflammation of the lung is rare but potentially fatal. Inflammation in the mouth and nausea can also develop. Severe relapses of arthritis can occur after methotrexate is discontinued. Folate (folic acid) tablets may decrease some of the side effects, such as mouth ulcers.

Hydroxychloroquine is given daily by mouth. Side effects, which are usually mild, include rashes, muscle aches, and eye problems. However, some eye problems can be permanent, so people taking hydroxychloroquine must have their eyes checked by an ophthalmologist before treatment begins and every 6 to 12 months during treatment. If the drug has not helped after 9 months, it is discontinued. Otherwise, hydroxychloroquine can be continued as long as necessary.

Sulfasalazine tablets can relieve symptoms and slow the development of joint damage. Sulfasalazine can also be used in people who have less severe rheumatoid arthritis or added to other drugs to boost their effectiveness. The dose is increased gradually, and improvement usually is seen within 3 months. Like the other DMARDs, it can cause stomach upset, liver problems, blood cell disorders, and rashes.

Gold compounds are not used anymore.

Corticosteroids: Corticosteroids, such as prednisone, are the most dramatically effective drugs for reducing inflammation anywhere in the body. Although corticosteroids are effective for short-term use, they may become less effective over time, and rheumatoid arthritis is usually active for years.

There is some controversy as to whether corticosteroids can slow the progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Furthermore, the long-term use of corticosteroids almost invariably leads to side effects, involving almost every organ in the body. Consequently, doctors usually reserve corticosteroids for short-term use when beginning treatment for severe symptoms (until a DMARD has taken effect) or in severe flare-ups when many joints are affected. They are also useful in treating inflammation outside of joints, for example, in the membranes covering the lungs (pleura) or in the sac surrounding the heart (pericardium). Because of the risk of side effects, the lowest effective dose is almost always used. When corticosteroids are injected into a joint, the person does not get the same side effects as when taking a corticosteroid by mouth (oral) or vein (intravenously). Corticosteroids can be injected directly into affected joints for fast, short-term relief.

DRUGS USED TO TREAT RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

DRUGS USED TO TREAT RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

| DRUG | SOME SIDE EFFECTS | COMMENTS |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | ||

| Diclofenac Ibuprofen Naproxen Many others (see table on page 646) |

Upset stomach Stomach ulcers Increased blood pressure Kidney problems Possibly increased risk of heart attack and stroke |

All NSAIDs treat the symptoms and decrease inflammation but do not alter the course of the disease. |

| Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors (coxibs), such as celecoxib | Risk of kidney problems Increased blood pressure Less risk of stomach ulcer than with other NSAIDs Possible increased risk of heart attack and stroke |

|

| Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) | ||

| Hydroxychloroquine |

Usually mild: Rashes Muscle aches Eye problems |

All DMARDs can slow progression of joint damage as well as gradually decrease pain and swelling. |

| Methotrexate | Liver disease Lung inflammation Nausea Increased susceptibility to infection Suppression of blood cell production in the bone marrow Mouth sores Decreased semen Hair loss |

|

| Sulfasalazine | Suppression of blood cell production in the bone marrow Stomach upset Liver problems Rashes |

|

| Corticosteroids | ||

| Prednisone | Numerous side effects throughout the body with long-term use: Weight gain Diabetes High blood pressure Thinning of bones |

Prednisone can reduce inflammation quickly. It may not be useful long term because of side effects. |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | ||

| Azathioprine Cyclophosphamide Cyclosporine Leflunomide |

Liver disease An increased susceptibility to infection and possibly cancer Suppression of blood cell production in the bone marrow Rashes and liver disease with leflunomide |

Azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporine are about as effective as other DMARDs but are more toxic. Cyclosporine does not affect the blood count but can reduce kidney function. Leflunomide is about as effective as methotrexate. |

| Immunosuppressive drugs (continued) | ||

| Adalimumab Etanercept Infliximab |

Potential risk of infection (particularly tuberculosis) or cancer

Liver disease Suppression of blood cell production in the bone marrow |

These drugs produce a dramatic, prompt response in most people. They can slow joint damage. |

| Anakinra | Pain and itching at injection site Infection Increased risk of infection and possibly cancer Suppression of blood cell production in the bone marrow |

Anakinra is probably less effective than adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab. |

| Rituximab | When the drug is being given: Itching at injection site Rashes Back pain High or low blood pressure Fever After the drug is given: Increased risk of infection and possibly cancer Suppression of blood cell production in the bone marrow |

Rituximab is used only when people do not improve after taking a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor and methotrexate. |

| Abatacept | Infection Headache Upper respiratory infection Sore throat Nausea |

Abatacept is used only when people do not improve after taking other drugs. |

| Adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab are tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. | ||

People who have peptic ulcer disease, high blood pressure, infections, diabetes, and glaucoma should use oral or intravenous corticosteroids only when being closely monitored for side effects by their doctor.

Immunosuppressive Drugs: Although corticosteroids suppress the immune system, other drugs do so even more potently and are referred to as immunosuppressive drugs. Each of these drugs can slow the progression of disease and decrease the damage to bones adjacent to joints. However, by interfering with the immune system, immunosuppressive drugs may increase the risks of infection and certain cancers. Such drugs include methotrexate (which is often the first DMARD used), leflunomide, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, rituximab, and abatacept.

Immunosuppressive drugs are effective in treating severe rheumatoid arthritis. They suppress the inflammation so that corticosteroids can be avoided or given in lower doses. But immunosuppressive drugs have their own potentially toxic and serious side effects, including liver disease, an increased susceptibility to infection, the suppression of blood cell production in the bone marrow, and, with cyclophosphamide, bleeding from the bladder. In addition, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide may increase the risk of cancer. In women who are considering pregnancy, immunosuppressive drugs should be used only after discussion with a doctor.

Leflunomide is a drug with benefits that are similar to those of methotrexate but that may be less likely to cause suppression of blood cell production and lung scarring. It can be given at the same time as methotrexate. It is given daily by mouth. The major side effects are rashes, liver dysfunction, hair loss, and diarrhea.

Etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab are TNF inhibitors and can be dramatically effective for people who do not respond sufficiently to methotrexate alone.

Corticosteroids: Uses and Side Effects

Corticosteroids are the strongest drugs available for reducing inflammation in the body. They are useful in any condition in which inflammation occurs, including rheumatoid arthritis and other connective tissue disorders, multiple sclerosis, and in emergencies such as brain swelling due to cancer, asthma attacks, and severe allergic reactions. When inflammation is severe, use of these drugs is often lifesaving.

Corticosteroids can be given by vein (especially in emergency situations), taken by mouth, or directly applied to the inflamed organ (as in inhaled versions for the lungs, in eye drops, and in a skin cream). For example, corticosteroids can be used as an inhaled preparation for treatment of asthma. They can be used as a nasal spray to treat hay fever (allergic rhinitis). They can be used as eye drops to treat eye inflammation (uveitis). They may be applied directly to an affected area for treatment of certain skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis.

Corticosteroids are prepared synthetically to have the same action as cortisol (or cortisone), a steroid hormone produced by the outer layer (cortex) of the adrenal glands—hence the name “corticosteroid.” Many synthetic corticosteroids are, however, more powerful than cortisol, and most are longer acting. Corticosteroids are chemically related to, but have different effects than, anabolic steroids (such as testosterone) that are produced by the body and sometimes abused by athletes.

Examples of corticosteroids include prednisone, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, betamethasone, beclomethasone, flunisolide, and fluticasone. All of these drugs are very strong (although strength depends on the dose used). Hydrocortisone is a milder corticosteroid that is available in over-the-counter skin creams.

Because corticosteroids reduce the body’s ability to fight infections by suppressing inflammation, they are used with extreme care when infections are present. Their use may worsen high blood pressure, heart failure, diabetes, peptic ulcers, and osteoporosis. Therefore, corticosteroids are used in such conditions only when their benefit is likely to exceed their risk.

When they are taken by mouth or by injection for more than about 2 weeks, corticosteroids should not be stopped abruptly. This is because corticosteroids inhibit the production of cortisol by the adrenal glands, and this production must be given time to recover. Thus, at the end of a course of corticosteroids, the dose is gradually reduced. It is important for a person who takes corticosteroids to follow the doctor’s instructions on dosage very carefully.

The long-term use of corticosteroids, particularly at higher doses and particularly when given by mouth or vein, invariably leads to many side effects, involving almost every organ in the body. Common side effects include thinning of the skin with stretch marks and bruising, high blood pressure, elevated blood sugar levels, cataracts, puffiness in the face (moon face) and abdomen, thinning of the arms and legs, poor wound healing, stunted growth in children, loss of calcium from the bones (which can lead to osteoporosis), hunger, weight gain, and mood swings. Because most of their effects are caused locally, inhaled corticosteroids and those that are applied directly to the skin have far fewer side effects than the version given by mouth or that given by vein.

Etanercept is given once or twice weekly by injection under the skin, and infliximab is given by vein every 8 weeks after loading doses. Adalimumab is injected under the skin once every 1 or 2 weeks. TNF is part of the body’s immune system, so inhibition of TNF can impair the body’s ability to fight infections. These drugs should be avoided in people who have active infections. Etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab can be used with methotrexate.

Anakinra is a recombinant interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist, which means it interrupts one of the major chemical pathways involved in inflammation. Anakinra is given as a single daily injection. Pain and itching at the injection site are the most common side effects. IL-1 is part of the immune system, so inhibiting IL-1 can impair the ability to fight infections. Anakinra can also suppress production of white blood cells. It should not be used with TNF inhibitors.

Rituximab decreases the number of B-cell lymphocytes, one of the white blood cells responsible for causing inflammation and for fighting infection. Because there is not as much evidence for the safety of rituximab as many other drugs, rituximab is usually reserved for people who do not improve enough after taking methotrexate and a TNF inhibitor. It is injected in a vein, as 2 doses, 2 weeks apart. Side effects, as with other immunosuppressive drugs, may include increased risk of infections. In addition, rituximab can cause effects while it is being given, such as rashes, nausea, back pain, itching, and high or low blood pressure.

Abatacept interferes with the communication between cells that coordinates inflammation. It is injected in the vein over several minutes. Abatacept is associated with several side effects and is used only for those who have not improved after using other drugs.

Other Treatments: Along with drugs to reduce joint inflammation, a treatment plan for rheumatoid arthritis should include nondrug therapies, such as exercise, physical or occupational therapy, and sometimes surgical treatment. Inflamed joints should be gently stretched so they do not freeze in one position. As the inflammation subsides, regular, active exercises can help, although a person should not exercise to the point of excessive tiredness (fatigue). For many people, exercise in water may be easier.

Treatment of tight joints consists of intensive exercises and occasionally the use of splints to gradually extend the joint. If drugs have not helped, surgical treatment may be needed. Surgically replacing knee or hip joints is the most effective way to restore mobility and function when the joint disease is advanced. Joints can also be removed or fused together, especially in the foot, to make walking less painful. The thumb can be fused to enable a person to grasp, and unstable vertebrae at the top of the neck can be fused to prevent them from compressing the spinal cord.

People who are disabled by rheumatoid arthritis can use several aids to accomplish daily tasks. For example, specially modified orthopedic or athletic shoes can make walking less painful, and devices such as grippers reduce the need to squeeze the hand forcefully.

Surgical repair must always be considered in terms of the total disease. For example, deformed hands and arms limit a person’s ability to use crutches during rehabilitation, and seriously affected knees and feet limit the benefits of hip surgery. Reasonable objectives for each person must be determined, and ability to function must be considered. Surgical repair may be performed while the disease is active.

Joint repair with prosthetic joint replacement is indicated if damage severely limits function. Total hip and knee replacements are most consistently successful.

Other Types of Inflammatory Arthritis

Several connective tissue diseases, including the spondyloarthropathies (also called spondyloarthritides), cause prominent joint inflammation. The spondyloarthropathies affect the joints and spine. These disorders share certain characteristics. For example, they may cause back pain, inflammation of the eye (uveitis), digestive symptoms, and rashes. Some are strongly associated with the HLA-B27 gene. Because they cause many of the same problems and share genetic characteristics, some experts think these disorders share similar causes and ways of causing symptoms. The spondyloarthropathies cause joint inflammation, similar to rheumatoid arthritis. However, in contrast to rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatoid factor (see page 564) is negative in the spondyloarthropathies (hence, they are also called the seronegative spondyloarthropathies). Among the spondyloarthropathies are psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis.

PSORIATIC ARTHRITIS

Psoriatic arthritis is a form of joint inflammation that occurs in some people who have psoriasis of the skin or nails.

Joint inflammation can develop in people who have psoriasis.

Joint inflammation can develop in people who have psoriasis.

Joints commonly involved include the hips, knees, and those closest to the tips of the fingers and toes.

Joints commonly involved include the hips, knees, and those closest to the tips of the fingers and toes.

The diagnosis is based on symptoms.

The diagnosis is based on symptoms.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, methotrexate, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) can help.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, methotrexate, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab) can help.

The disease resembles rheumatoid arthritis but does not produce the antibodies characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis. Psoriatic arthritis occurs in about 5 to 40% of people with psoriasis (a skin condition causing flare-ups of red, scaly rashes and thickened, pitted nails—see page 1292). The cause of psoriatic arthritis is unknown.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Inflammation often affects joints closest to the tips of the fingers and toes, although other joints, including the hips, knees and spine, are often affected as well. Often the joints of the upper extremities are affected more. Back pain may be present. The joints may become swollen and deformed when inflammation is chronic. Psoriatic arthritis often involves joints less symmetrically than rheumatoid arthritis and involves fewer joints. The psoriasis rash may appear before or after arthritis develops. Sometimes the rash is not noticed because it is hidden in the scalp or creases of the skin such as between the back of the buttocks and thigh. The skin and joint symptoms sometimes appear and disappear together.

The diagnosis is made by identifying the characteristic joint inflammation in a person who has arthritis and psoriasis or a family history of psoriasis. There are no tests to confirm the diagnosis, but x-rays help show the extent of joint damage.

Prognosis and Treatment

The prognosis for psoriatic arthritis is usually better than that for rheumatoid arthritis because fewer joints are affected. Nonetheless, the joints can be severely damaged.

Treatment is aimed at controlling the skin rash and relieving the joint inflammation. Several drugs that are effective in treating rheumatoid arthritis are also used to treat psoriatic arthritis, particularly nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), methotrexate, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors.

Some people take methoxsalen (psoralen) by mouth and undergo psoralen plus ultraviolet A light treatments. This combination relieves the skin symptoms and most of the joint inflammation but may not help inflammation of the spine.

REACTIVE ARTHRITIS

Reactive arthritis (sometimes called Reiter syndrome) is inflammation of the joints and tendon attachments at the joints, often related to an infection.

Joint pain and inflammation can occur in response to an infection, usually of the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract.

Joint pain and inflammation can occur in response to an infection, usually of the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract.

Tendon inflammation, skin rashes, and red eye are also common.

Tendon inflammation, skin rashes, and red eye are also common.

The diagnosis is based on symptoms.

The diagnosis is based on symptoms.

NSAIDs, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, and methotrexate may help treat the symptoms.

NSAIDs, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, and methotrexate may help treat the symptoms.

Reactive arthritis is so called because the joint inflammation seems to be a reaction to an infection originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract.

There are two forms of reactive arthritis. One form seems to occur with sexually transmitted diseases, such as a chlamydial infection, and occurs most often in men aged 20 to 40. The other form usually follows an intestinal infection such as shigellosis, salmonellosis, or a Campylobacter infection. Most people who have these infections do not develop reactive arthritis. People who develop reactive arthritis after exposure to these infections seem to have a genetic predisposition to this type of reaction, related in part to the same gene found in people who have ankylosing spondylitis (see page 571). There is some evidence that the chlamydia bacteria and possibly other bacteria actually spread to the joints, but the roles of the infection and the immune reaction to it are not clear.

Reactive arthritis may be accompanied by inflammation of the conjunctiva (see page 1437) and the mucous membranes (such as those of the mouth and genitals) and by a distinctive rash. This form of reactive arthritis previously was called Reiter syndrome.

Symptoms

Joint pain and inflammation may be mild or severe. Several joints are usually affected at once—especially the knees, toe joints, and areas where tendons are attached to bones, such as at the heels. Often, the large joints of the lower limbs are affected the most. Reactive arthritis often involves joints less symmetrically than rheumatoid arthritis.

Tendons may be inflamed and painful. Back pain may occur, usually when the disease is severe.

Inflammation of the urethra (the channel that carries urine from the bladder to the outside of the body) can develop, usually about 7 to 14 days after the infection. In men, inflammation of the urethra causes moderate pain and a discharge from the penis or a rash on the glans of the penis (balanitis circinata). The prostate gland may be inflamed and painful. The genital and urinary symptoms in women, if any occur, are usually mild, consisting of a slight vaginal discharge or uncomfortable urination. Other symptoms include a low-grade fever and excessive tiredness (fatigue).

The conjunctiva (the membrane that lines the eyelid and covers the eyeball) can become red and inflamed, causing itching or burning, sensitivity to light, and excessive tearing. Small and usually painless or sometimes tender sores can develop in the mouth. Occasionally, a distinctive rash of hard, thickened spots may develop on the skin, especially of the palms and soles (keratoderma blennorrhagicum). Yellow deposits may develop under the fingernails and toenails.

Rarely, heart and blood vessel complications (such as inflammation of the aorta), inflammation of the membranes covering the lungs, dysfunction of the aortic valve, and brain and spinal cord symptoms or peripheral nervous system (which includes all the nerves outside the brain and spinal cord) symptoms may develop.

In most people, the initial symptoms disappear in 3 or 4 months, but up to 50% of people experience recurring joint inflammation or other symptoms over several years. Joint and spinal deformities may develop if the symptoms persist or recur frequently. Some people who have reactive arthritis become permanently disabled.

Diagnosis

The combination of joint symptoms and a preceding infection, particularly if there are genital, urinary, skin, and eye symptoms, leads a doctor to suspect reactive arthritis. Because these symptoms may not appear simultaneously, the disease may not be diagnosed for several months. No simple laboratory tests are available to confirm the diagnosis, but x-rays are often performed to assess the status of joints. Tests may be done to exclude other disorders that can cause similar symptoms.

Treatment

When the disease affects the genitals or urinary tract, antibiotics are given to treat the infection, but treatment is not always successful and its optimal duration is not known.

Joint inflammation is usually treated with an NSAID. Sulfasalazine or drugs that suppress the immune system (such as azathioprine or methotrexate) may be used, as in rheumatoid arthritis. Physical therapy is helpful in maintaining joint mobility during the recovery phase.

Conjunctivitis and skin sores do not usually need to be treated, although severe eye inflammation (uveitis) may require corticosteroid and dilating eyedrops.

ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS

Ankylosing spondylitis is a disorder characterized by inflammation of the spine and large joints, resulting in stiffness and pain.

Joint pain, back stiffness, and eye inflammation are common.

Joint pain, back stiffness, and eye inflammation are common.

The diagnosis is based on symptoms and x-rays.

The diagnosis is based on symptoms and x-rays.

NSAIDs and sometimes sulfasalazine or methotrexate can help the arthritis in limbs.

NSAIDs and sometimes sulfasalazine or methotrexate can help the arthritis in limbs.

Drugs that inhibit tumor necrosis factor are very effective for spine and limb arthritis.

Drugs that inhibit tumor necrosis factor are very effective for spine and limb arthritis.

The disease is 3 times more common among men than women, developing most commonly between the ages of 20 and 40. Its cause is not known, but the disease tends to run in families, indicating that genetics plays a role. Ankylosing spondylitis is 10 to 20 times more common among people whose parents or siblings have it.

Symptoms

Mild to moderate flare-ups of inflammation generally alternate with periods of almost no symptoms.

The most common symptom is back pain, which varies in intensity from one episode to another and from one person to another. Pain is often worse at night and in the morning. Early morning stiffness that is relieved by activity is also very common. Pain in the lower back and the associated muscle spasms are often relieved by bending forward. Therefore, people often assume a stooped posture, which can lead to a permanent bent-over position. In others, the spine becomes noticeably straight and stiff.

Loss of appetite, low-grade fever, weight loss, excessive tiredness (fatigue), and anemia can accompany the back pain. If the joints connecting the ribs to the spine are inflamed, the pain may limit the ability to expand the chest to take a deep breath. Stiffness (fusion) of the spine can restrict the ability to expand the chest wall as well. Occasionally, pain starts in large joints, such as the hips, knees, and shoulders.

One third of the people have recurring attacks of mild eye inflammation (uveitis), which usually does not impair vision if treated promptly. In a few people, inflammation of a heart valve results in a permanently damaged valve, or other problems can affect the heart or aorta. If damaged vertebrae press against nerves or the spinal cord, numbness, weakness, or pain can develop in the area supplied by the affected nerves. Cauda equina (horse’s tail) syndrome is an occasional complication (see box on page 800). Achilles tendinitis can develop.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on the pattern of symptoms and on x-rays of the spine and affected joints, which show a wearing away (erosion) of the joint between the spine and the hip bone (sacroiliac joint) and the formation of bony bridges between the vertebrae, making the spine stiff. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), a test that measures the rate at which red blood cells settle to the bottom of a test tube containing blood, tends to be high, indicating inflammation.

Prognosis

Most people develop some disabilities but can still lead normal, productive lives. In some people, the disease is more progressive, causing severe deformities. The prognosis is discouraging for people who develop extreme stiffness of the spine.

Treatment

Treatment focuses on relieving back and joint pain, maintaining range of motion in the joints, preventing damage in other organs, and preventing or correcting spinal deformities. NSAIDs can reduce the pain and inflammation, thus enabling people to do important exercises to retain posture, including stretching and deep breathing. Sulfasalazine or methotrexate may help the pain in joints other than those of the back. The TNF inhibitors etanercept, adalimumab, or infliximab can relieve back pain and inflammation.

Corticosteroid eye drops may help in the short-term treatment of inflammation of the eyes, and an occasional corticosteroid injection may be helpful for 1 or 2 joints other than the spine. Muscle relaxants and opioid analgesics are occasionally used, but for only brief periods to relieve severe pain and muscle spasms. If hips or knees become eroded or fixed in a bent position, surgical treatment to replace the joint can relieve pain and restore function.

The long-range goals of treatment are to maintain proper posture and develop strong back muscles. Daily exercises strengthen the muscles that oppose the tendency to bend and stoop. It has been suggested that people spend some time each day—often while reading—lying on their stomach propped up on their elbows because this position extends the back and helps to keep the back flexible. Because chest wall motion can be restricted, which impairs lung function, cigarette smoking, which also impairs lung function, is strongly discouraged.

OTHER SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIES

Spondyloarthropathy can develop in association with digestive conditions (sometimes called enteropathic arthritis), such as inflammatory bowel disease, intestinal bypass surgery, or Whipple’s disease. Juvenile-onset spondyloarthropathy affects the lower extremities, often affects joints on opposite sides of the body to different degrees, and begins most commonly in boys aged 7 to 16. Spondyloarthropathy can also develop in people with no characteristics of other specific spondyloarthropathy (undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy). Treatment of the arthritis of these other spondyloarthropathies is similar to that of treatment of reactive arthritis (see page 570).

Charcot’s Joints

Charcot’s joints (neurogenic arthropathy, neuropathic arthropathy) is progressive joint destruction, often very rapid, that develops because people cannot sense pain and thus are not aware of the early signs of joint damage.

When certain nerves are damaged, people may become unable to sense pain. A variety of disorders, such as diabetes mellitus, spinal cord disorders, and syphilis, can damage these nerves. People with nerve damage may injure a joint many times, or even fracture it, without noticing. Injuries may occur for years before the joint malfunctions. However, once it malfunctions, the joint may be permanently destroyed within a few months.

In its early stages, Charcot’s joints appear similar to osteoarthritis, because the joint is stiff and fluid accumulates in it. Usually, the joint is not painful or is less painful than would be expected considering the amount of joint damage. If the disorder progresses rapidly, the joint can become extremely painful. In these cases, the joint is usually swollen because of excess fluid and abnormal bone growth. It may look deformed because it has been fractured and ligaments have stretched, allowing the bones to slip out of place. Moving the joint may cause a coarse, grating sound because of bone fragments floating in the joint. The joint may feel like a “bag of bones.”

Any joint can be affected depending on where the nerve damage is—most commonly, the knee or ankle or, in people who have diabetes, the foot. Often, only one joint is affected, and usually not more than two or three.

Doctors suspect Charcot’s joints when people have a nerve disorder and joint problems. X-rays can detect joint damage, which often includes calcium deposits and abnormal bone growth. Sometimes Charcot’s joints can be prevented by taking care of the feet and by avoiding injuries. Splints or special boots can sometimes help protect vulnerable joints. Treatment of the underlying nerve disorder can sometimes slow or even reverse joint damage. Diagnosing and immobilizing painless fractures and splinting unstable joints can help stop or minimize the damage. Hips and knees may be surgically repaired or replaced. However, artificial joints often loosen prematurely.