CHAPTER 114

Stroke

A stroke occurs when an artery to the brain becomes blocked or ruptures, resulting in death of an area of brain tissue (cerebral infarction) and causing sudden symptoms.

Most strokes are ischemic (usually due to blockage of an artery), but some are hemorrhagic (due to rupture of an artery).

Most strokes are ischemic (usually due to blockage of an artery), but some are hemorrhagic (due to rupture of an artery).

Transient ischemic attacks resemble ischemic strokes except the symptoms resolve within 1 hour.

Transient ischemic attacks resemble ischemic strokes except the symptoms resolve within 1 hour.

Symptoms occur suddenly and can include muscle weakness, paralysis, abnormal or lost sensation on one side of the body, difficulty speaking, confusion, problems with vision, dizziness, and loss of balance and coordination.

Symptoms occur suddenly and can include muscle weakness, paralysis, abnormal or lost sensation on one side of the body, difficulty speaking, confusion, problems with vision, dizziness, and loss of balance and coordination.

Diagnosis is based on symptoms, but imaging and blood tests are also done.

Diagnosis is based on symptoms, but imaging and blood tests are also done.

Recovery after a stroke depends on many factors, such as the location and amount of damage, the person’s age, and the presence of other disorders.

Recovery after a stroke depends on many factors, such as the location and amount of damage, the person’s age, and the presence of other disorders.

Controlling high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, and high blood sugar levels and not smoking help prevent strokes.

Controlling high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, and high blood sugar levels and not smoking help prevent strokes.

Treatment may include drugs to make blood less likely to clot or to break up clots and sometimes surgery.

Treatment may include drugs to make blood less likely to clot or to break up clots and sometimes surgery.

A stroke is called a cerebrovascular disorder because it affects the brain (cerebro-) and the blood vessels (vascular).

In Western countries, strokes are the third most common cause of death and the most common cause of disabling neurologic damage. In the United States, over 600,000 people have a stroke and about 160,000 die of stroke each year. Strokes are much more common among older people than among younger adults, usually because the disorders that lead to strokes progress over time. Over two thirds of all strokes occur in people older than 65. Slightly more than 50% of all strokes occur in men, but more than 60% of deaths due to stroke occur in women, possibly because women are on average older when the stroke occurs. Blacks are more likely than whites to have a stroke and to die of it.

Types: There are two types of strokes: ischemic and hemorrhagic. About 80% of strokes are ischemic—usually due to a blocked artery, often blocked by a blood clot. Brain cells, thus deprived of their blood supply, do not receive enough oxygen and glucose (a sugar), which are carried by blood. The damage that results depends on how long brain cells are deprived of blood. If they are deprived for only a brief time, brain cells are stressed, but they may recover. If brain cells are deprived longer (but possibly for only several minutes), brain cells die, and some functions may be lost. However, in such cases, a different area of the brain can sometimes learn how to do the functions previously done by the damaged area.

Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), sometimes called ministrokes, are often an early warning sign of an impending ischemic stroke. They are caused by a brief interruption of the blood supply to part of the brain. Because the blood supply is restored quickly, brain tissue may not die, as it does in a stroke.

The other 20% of strokes are hemorrhagic—due to bleeding in or around the brain. In this type of stroke, a blood vessel ruptures, interfering with normal blood flow and allowing blood to leak into brain tissue. Blood that comes into direct contact with brain tissue irritates the tissue and can cause scarring, leading to seizures.

Risk Factors: The major risk factors for both types of stroke are

Atherosclerosis (narrowing or blockage of arteries by patchy deposits of fatty material in the walls of arteries)

Atherosclerosis (narrowing or blockage of arteries by patchy deposits of fatty material in the walls of arteries)

High cholesterol levels

High cholesterol levels

High blood pressure

High blood pressure

Diabetes

Diabetes

Smoking

Smoking

Atherosclerosis is a more important risk factor for ischemic stroke, and high blood pressure is a more important risk factor for hemorrhagic stroke. These risk factors can be controlled to some extent.

Other risk factors include

Having relatives who have had a stroke

Having relatives who have had a stroke

Consuming too much alcohol

Consuming too much alcohol

Using cocaine or amphetamines

Using cocaine or amphetamines

Having an abnormal heart rhythm called atrial fibrillation

Having an abnormal heart rhythm called atrial fibrillation

Having inflamed blood vessels (vasculitis)

Having inflamed blood vessels (vasculitis)

For hemorrhagic stroke, risk factors also include using anticoagulants, having a bulge (aneurysm) in arteries within the skull, and having an abnormal connection between arteries and veins (arteriovenous malformation).

The incidence of strokes has declined in recent decades, mainly because people are more aware of the importance of controlling high blood pressure and high cholesterol levels and stopping cigarette smoking. Controlling these factors reduces the risk of atherosclerosis.

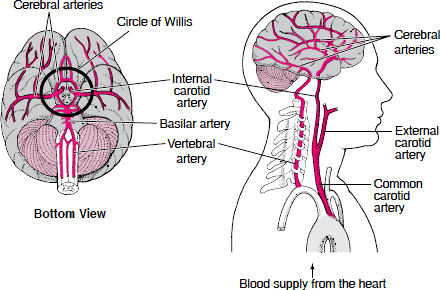

Supplying the Brain With Blood

Blood is supplied to the brain through two pairs of large arteries:

Internal carotid arteries, which carry blood from the heart along the front of the neck

Internal carotid arteries, which carry blood from the heart along the front of the neck

Vertebral arteries, which carry blood from the heart along the back of the neck

Vertebral arteries, which carry blood from the heart along the back of the neck

In the skull, the vertebral arteries unite to form the basilar artery (at the back of the head). The internal carotid arteries and the basilar artery divide into several branches, including the cerebral arteries. Some branches join to form a circle of arteries (circle of Willis) that connect the vertebral and internal carotid arteries. Other arteries branch off from the circle of Willis like roads from a traffic circle. The branches carry blood to all parts of the brain.

When the large arteries that supply the brain are blocked, some people have no symptoms or have only a small stroke. But others with the same sort of blockage have a massive ischemic stroke. Why? Part of the explanation is collateral arteries. Collateral arteries run between other arteries, providing extra connections. These arteries include the circle of Willis and connections between the arteries that branch off from the circle. Some people are born with large collateral arteries, which can protect them from strokes. Then when one artery is blocked, blood flow continues through a collateral artery, sometimes preventing a stroke. Other people are born with small collateral arteries. Small collateral arteries may be unable to pass enough blood to the affected area, so a stroke results.

The body can also protect itself against strokes by growing new arteries. When blockages develop slowly and gradually (as occurs in atherosclerosis), new arteries may grow in time to keep the affected area of the brain supplied with blood and thus prevent a stroke. If a stroke has already occurred, growing new arteries can help prevent a second stroke (but cannot reverse damage that has been done).

Symptoms

Symptoms of a stroke or transient ischemic attack occur suddenly. They vary depending on the precise location of the blockage or bleeding in the brain (see page 677 and art on page 678). Each area of the brain is supplied by specific arteries. For example, if an artery supplying the area of the brain that controls the left leg’s muscle movements is blocked, the leg becomes weak or paralyzed. If the area of the brain that senses touch in the right arm is damaged, sensation in the right arm is lost.

Because early treatment can help limit loss of function and sensation, everyone should know what the early symptoms of stroke are. People who have any of these symptoms should see a doctor immediately, even if the symptom goes away quickly.

Most strokes, whether ischemic or hemorrhagic, typically cause one or more of the following symptoms:

Sudden weakness or paralysis on one side of the body (for example, half of the face, one arm or leg, or all of one side)

Sudden weakness or paralysis on one side of the body (for example, half of the face, one arm or leg, or all of one side)

Sudden loss of sensation or abnormal sensations on one side of the body

Sudden loss of sensation or abnormal sensations on one side of the body

Sudden difficulty speaking, sometimes with slurred speech

Sudden difficulty speaking, sometimes with slurred speech

Sudden confusion, with difficulty understanding speech

Sudden confusion, with difficulty understanding speech

Sudden dimness, blurring, or loss of vision, particularly in one eye

Sudden dimness, blurring, or loss of vision, particularly in one eye

Sudden dizziness or loss of balance and coordination, leading to falls

Sudden dizziness or loss of balance and coordination, leading to falls

Symptoms of a transient ischemic attack are the same, but they usually disappear within minutes and rarely last more than 1 hour.

Symptoms of a hemorrhagic stroke may also include the following:

Sudden severe headache

Sudden severe headache

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting

Temporary or persistent loss of consciousness

Temporary or persistent loss of consciousness

Very high blood pressure

Very high blood pressure

Other symptoms that may occur early include problems with memory, thinking, attention, or learning. People may be unable to recognize parts of the body and may be unaware of the stroke’s effects. The peripheral field of vision may be reduced, and hearing may be partially lost. Dizziness and vertigo may develop or persist. Control of bowel or bladder function may be lost.

Later symptoms may include stiffening and spasms of the muscles (spasticity) and inability to control emotions. A stroke can cause depression, or people may feel depressed because of the stroke.

In most people who have had an ischemic stroke, loss of function is usually greatest immediately after the stroke occurs. However, in about 15 to 20%, the stroke is progressive, causing greatest loss of function after a day or two. In people who have had a hemorrhagic stroke, function usually is lost progressively over minutes to hours.

Over days to months, some function is usually regained because even though some brain cells die, others are only stressed and may recover. Also, certain areas of the brain can sometimes switch to the functions previously done by the damaged part—a characteristic called plasticity. However, the early effects of a stroke, including paralysis, can become permanent. Muscles that are not used usually become permanently spastic and stiff, and painful muscle spasms may occur. Walking, swallowing, physically saying words clearly, and doing daily activities may remain difficult. Various problems with memory, thinking, attention, learning, or controlling emotions may persist. Depression, impairments in hearing or vision, or vertigo may be continuing problems. Control of bowel or bladder function may be permanently impaired.

Why Strokes Affect Only One Side of the Body

Strokes usually damage only one side of the brain. Because nerves in the brain cross over to the other side of the body, symptoms appear on the side of the body opposite the damaged side of the brain.

Complications: When a stroke is severe, the brain swells, increasing pressure within the skull. Increased pressure can damage the brain directly or indirectly by forcing the brain downward in the skull. The brain may be forced through the rigid structures that separate the brain into compartments, resulting in a serious problem called herniation (see art on page 735). The pressure affects the respiratory center in the lower part of the brain stem and can cause irregular breathing, loss of consciousness, coma, and death.

The symptoms caused by a stroke can lead to other problems. If swallowing is difficult, people may inhale food, fluids, or other particles from the mouth. Such inhalation (called aspiration) can cause aspiration pneumonia, which may be serious. Difficulty swallowing can also interfere with eating, resulting in undernutrition and dehydration. Not being able to move can result in pressure sores, muscle loss, and the formation of blood clots in deep veins of the legs and groin (deep vein thrombosis). Clots can break off, travel through the bloodstream, and block an artery to a lung (pulmonary embolism). If bladder control is impaired, urinary tract infections are more likely to develop.

Diagnosis

Symptoms suggest the diagnosis, but tests are needed to help doctors determine the following:

Whether stroke has occurred

Whether stroke has occurred

Whether it is ischemic or hemorrhagic

Whether it is ischemic or hemorrhagic

Whether immediate treatment is required

Whether immediate treatment is required

Computed tomography (CT—see page 2037) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI—see page 2040) of the brain is done. These tests can detect most hemorrhagic strokes, except for some subarachnoid hemorrhages. These tests can also detect many ischemic strokes but sometimes not until several hours after symptoms appear. The blood sugar level is measured immediately because a low blood sugar level (hypoglycemia) can cause symptoms similar to those of stroke.

Doctors evaluate people who have had a stroke for problems that can contribute to or cause a stroke, such as infection, a low blood oxygen level, and dehydration. Tests are done as needed. People are asked about depression. The ability to swallow is evaluated, sometimes with x-rays taken after a radiopaque dye such as barium is swallowed. Depending on the type of stroke, more tests are done to identify the cause.

Prognosis

Certain factors suggest that the outcome of a stroke is likely to be poor. Strokes that cause unconsciousness or that affect a large part of the left side of the brain (which is responsible for language) may be particularly grave.

In adults who have had an ischemic stroke, problems that remain after 6 months are likely to be permanent, but children continue to improve slowly for many months. Older people fare less well than younger people. For people who already have other serious disorders (such as dementia), recovery is more limited.

If a hemorrhagic stroke is not massive and pressure within the brain is not very high, the outcome is likely to be better after than that after an ischemic stroke. Blood (in a hemorrhagic stroke) does not damage brain tissue as much as an inadequate supply of oxygen (in an ischemic stroke) does.

Prevention

Preventing strokes is preferable to treating them. The main strategy for preventing a first stroke is managing the major risk factors. High blood pressure (see page 333) and diabetes (see page 1005) should be controlled. Cholesterol levels should be measured and, if high, lowered to reduce the risk of atherosclerosis (see page 961). Smoking and use of amphetamines or cocaine should be stopped, and alcohol should be limited to no more than 2 drinks a day. Exercising regularly and, if overweight, losing weight help people control high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol levels. Having regular checkups enables a doctor to identify risk factors for stroke so that they can be managed quickly.

If people have had an ischemic stroke, taking an antiplatelet drug can reduce the risk of another ischemic stroke. Antiplatelet drugs make platelets less likely to clump and form clots, a common cause of ischemic stroke. (Platelets are tiny cell-like particles in blood that help it clot in response to damaged blood vessels.) Aspirin, one of the most effective antiplatelet drugs, is usually prescribed. One adult’s tablet or 1 children’s tablet (which is about one fourth the dose of an adult aspirin) is taken each day. Either dose seems to prevent strokes about equally well. Taking a combination tablet that contains a low dose of aspirin and dipyridamole (an antiplatelet drug) is slightly more effective than taking aspirin alone. Clopidogrel, another antiplatelet drug, is also slightly more effective than aspirin alone. It may be given to people who cannot tolerate aspirin. Some people are allergic to antiplatelet drugs or similar drugs and cannot take them. Also, people who have gastrointestinal bleeding should not take antiplatelet drugs.

If an ischemic stroke or a transient ischemic attack is due to blood clots originating in the heart, warfarin, an anticoagulant, may be given to inhibit blood clotting. Because taking warfarin and an antiplatelet drug or taking aspirin plus clopidogrel greatly increases the risk of bleeding, these drugs are rarely used together for stroke prevention.

Treatment

Anyone with symptoms of a stroke should seek medical attention immediately.

Doctors check the person’s vital functions, such as heart rate, breathing, temperature, and blood pressure, to make sure they are adequate. If they are not, measures to correct them are taken immediately. For example, if people are in a coma or unresponsive (as may result from brain herniation), mechanical ventilation (with a breathing tube inserted through the mouth or nose) may be needed to help them breathe. If symptoms suggest that pressure within the skull is high, drugs may be given to reduce swelling in the brain, and a monitor may be put in the brain to periodically measure the pressure.

Other treatments used during the first hours depend on the type of stroke. These treatments include drugs (such as antiplatelet drugs, anticoagulants, drugs to break up clots, and drugs to control high blood pressure) and surgery to remove blood that has accumulated.

Later and ongoing treatments focus on preventing subsequent strokes, treating and preventing problems that strokes can cause, and helping people regain as much function as possible (rehabilitation).

Rehabilitation: Intensive rehabilitation can help many people overcome disabilities after a stroke (see page 53). The exercises and training of rehabilitation encourage unaffected areas of the brain to learn to perform functions that were done by the damaged area. Also, people are taught new ways to use muscles unaffected by the stroke to compensate for losses in function.

The goals of rehabilitation are the following:

To regain as much normal function as possible

To regain as much normal function as possible

To maintain and improve physical condition

To maintain and improve physical condition

To help people relearn old skills and learn new ones as needed

To help people relearn old skills and learn new ones as needed

Success depends on the area of the brain damaged and the person’s general physical condition, functional and cognitive abilities before the stroke, social situation, learning ability, and attitude. Patience and perseverance are crucial. Participating actively in the rehabilitation program can help people avoid or lessen depression.

Rehabilitation is started in the hospital as soon as people are physically able—usually within 1 or 2 days of admission. After discharge from the hospital, rehabilitation can be continued on an outpatient basis, in a nursing home, in a rehabilitation center, or at home. Occupational and physical therapists can suggest ways to make life easier and the home safer for people with disabilities.

Family members and friends can contribute to a person’s rehabilitation by keeping in mind what effects a stroke can have, so that they can better understand and support the person. Support groups can provide emotional encouragement and practical advice for people who have had a stroke and for those who care for them.

End-of-Life Issues

For some people who have had a stroke, quality of life is predicted to remain very poor despite treatment. For such people, care focuses on control of pain, comfort measures, and provision of fluids and nourishment. People who have had a stroke should establish advance directives (see page 69) as soon as possible because the recurrence and progression of strokes are unpredictable. Advance directives can help a doctor determine what kind of medical care people want if they become unable to make these decisions.

Transient Ischemic Attacks

A transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a disturbance in brain function that lasts less than 1 hour and results from a temporary blockage of the brain’s blood supply.

The cause and symptoms of a TIA are the same as those of an ischemic stroke.

The cause and symptoms of a TIA are the same as those of an ischemic stroke.

TIAs differ from ischemic strokes because symptoms resolve within 1 hour.

TIAs differ from ischemic strokes because symptoms resolve within 1 hour.

Symptoms suggest the diagnosis, but imaging and blood tests are also done.

Symptoms suggest the diagnosis, but imaging and blood tests are also done.

Controlling high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, and high blood sugar levels and not smoking are recommended.

Controlling high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, and high blood sugar levels and not smoking are recommended.

Drugs to make blood less likely to clot and sometimes surgery (carotid endarterectomy) or angioplasty are used to reduce the risk of stroke after a TIA.

Drugs to make blood less likely to clot and sometimes surgery (carotid endarterectomy) or angioplasty are used to reduce the risk of stroke after a TIA.

TIAs may be a warning sign of an impending ischemic stroke. People who have had a TIA are much more likely to have a stroke than those who have not. About half of these strokes occur within 1 year of the TIA, and many occur within a few days of the TIA. Recognizing a TIA and having the cause identified can help prevent a stroke.

TIAs are most common among middle-aged and older people.

TIAs differ from ischemic strokes because, after a TIA, symptoms resolve completely and quickly. Experts used to think that symptoms resolved more quickly because TIAs did not cause any permanent brain damage. That is, no brain cells died. However, most experts now think that TIAs are small ischemic strokes. That is, in TIAs, as in ischemic strokes, brain cells die. The difference is that in TIAs, the damage is usually very small.

Causes

Causes of TIAs and ischemic strokes are mostly the same. Most TIAs occur when a piece of a blood clot (thrombus) or of fatty material (atheroma, or plaque) due to atherosclerosis breaks off from the heart or from the wall of an artery, travels through the bloodstream (becoming an embolus), and lodges in an artery that supplies the brain (see page 724). Occasionally, TIAs result from a very low oxygen level in the blood, a severe deficiency of red blood cells (anemia), carbon monoxide poisoning, thickened blood (as in polycythemia), or very low blood pressure (hypotension), especially when the arteries to the brain are already narrowed (as in people with atherosclerosis).

PREVENTING AND TREATING PROBLEMS AFTER A STROKE

| PROBLEM | MEASURES |

| Blood clots in the legs | To prevent blood clots, doctors may give anticoagulants, such as heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin, put elastic or air-filled support stockings on the person’s legs to improve blood circulation, or both. Moving the legs, which improves blood flow, can also help. People, if able, are encouraged to walk or simply move their legs (for example, extending and flexing their ankles). If people cannot move their legs, a therapist or other staff member moves their legs for them (called passive exercise). |

| Pressure sores | Nurses, other staff members, or caregivers should frequently turn or reposition people who are confined to a bed or wheelchair. Areas likely to develop pressure sores should be inspected every day. |

| Permanent shortening of muscles that limits movement (contractures) | Moving the limbs can prevent contractures. People, if able, are encouraged to move and change positions regularly. Or a therapist or other staff member moves their limbs for them and makes sure the limbs are placed in appropriate resting positions. Sometimes splints are used to keep the limbs in place. |

| Difficulty swallowing | People are evaluated for difficulty swallowing. If they have difficulty, care is taken to provide them with enough fluids and nourishment. Sometimes learning simple techniques (for example, how to position the head, how to breathe when swallowing) can help the person swallow safely. Tube feedings may be necessary until the ability to swallow returns. |

| Difficulty breathing | If people smoke, they are encouraged to stop. Therapists also teach them to do deep breathing exercises and to cough to clear the airways. Therapists may provide a handheld breathing device. If needed, oxygen is provided through a face mask or a tube inserted in the nose or in the mouth. |

| Urinary tract infections | If possible, a urinary catheter, which can cause urinary infections, is not used. If a catheter is needed, it is removed as soon as possible. |

| Discouragement and depression | Doctors discuss the effects of the stroke with affected people and their family members or other caregivers. The discussion includes the type of recovery that can be expected and ways to cope with limitations of function. People and their caregivers are put in contact with stroke support groups. Formal counseling or drugs may be necessary to treat depression. |

Symptoms

Symptoms of a TIA develop suddenly. They are identical to those of an ischemic stroke (see page 725) but are temporary and reversible. They usually last less than 5 minutes and not longer than 1 hour. TIAs recur in about 5% of people with atherosclerosis. People may have several in 1 day or only two or three in several years.

Diagnosis

People who have a sudden symptom similar to any symptom of a stroke, even if it quickly resolves, should go immediately to an emergency department. Such a symptom suggests a TIA. However, other disorders, including seizures, brain tumors, migraine headaches, and abnormally low levels of sugar in the blood (hypoglycemia), cause similar symptoms, so further evaluation is needed.

If doctors suspect that a TIA has occurred, they evaluate people rapidly, usually in the hospital, because a stroke may occur soon after a TIA. Doctors check for risk factors for stroke by asking people questions, reviewing their medical history, and doing blood tests.

Imaging tests, such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are done to check for evidence of a stroke, bleeding, and brain tumors. A specialized type of MRI, called diffusion MRI, can show areas of brain tissue that are not functioning and thus help doctors diagnose a TIA (or an ischemic stroke). However, diffusion MRI is not always available.

Other imaging tests help determine whether an artery to the brain is blocked, which artery is blocked, and how complete the blockage is. These tests provide images of the arteries that carry blood through the neck to the brain (the internal carotid arteries and the vertebral arteries) and the arteries of the brain (such as the cerebral arteries). Color Doppler ultrasonography (used only for the internal carotid arteries), magnetic resonance angiography (see page 2041), or CT angiography (see page 2039) may be done. Sometimes if the stroke is severe, cerebral angiography (using a dye injected through a catheter) is done (see page 2036).

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Even if symptoms of a stroke resolve within a few minutes, people should still go to the emergency department immediately.

Treatment

Treatment of TIAs is aimed at preventing a stroke. It is the same as that after an ischemic stroke.

The first step in preventing a stroke is to control, if possible, the major risk factors for it: high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, smoking, and diabetes. Taking an antiplatelet drug, such as aspirin, a combination tablet of low-dose aspirin plus dipyridamole, or clopidogrel, reduces the chance that clots will form and cause TIAs or ischemic strokes. (Platelets are tiny cell-like particles in the blood that help it clot in response to damaged blood vessels.)

The degree of narrowing in the carotid arteries helps doctors estimate the risk of a stroke or subsequent TIAs and thus determine the treatment. If people are thought to be at high risk (for example, if the carotid artery is narrowed at least 70%), an operation to widen the artery (called carotid endarterectomy) may be done to reduce the risk (see page 728). Carotid endarterectomy usually involves removing atheromas and clots in the internal carotid artery. However, the operation can trigger a stroke because the operation may dislodge clots or other material that can then travel through the bloodstream and block an artery. However, after the operation, the risk of stroke is lower for several years than it is when drugs are used.

In other narrowed arteries, such as the vertebral arteries, endarterectomy may not be possible because the operation is riskier to perform in these arteries than in the internal carotid arteries.

If people are not healthy enough to have surgery, angioplasty with stenting (see art on page 405) may be done. For this procedure, a thin, flexible tube (catheter) with a balloon at its tip is threaded into the narrowed artery. The balloon is then inflated for several seconds to widen the artery. To keep the artery open, doctors insert a tube made of wire mesh (a stent) into the artery.

Ischemic Stroke

An ischemic stroke is death of an area of brain tissue (cerebral infarction) resulting from an inadequate supply of blood and oxygen to the brain due to blockage of an artery.

Ischemic stroke usually results when an artery to the brain is blocked, often by a blood clot or a fatty deposit due to atherosclerosis.

Ischemic stroke usually results when an artery to the brain is blocked, often by a blood clot or a fatty deposit due to atherosclerosis.

Symptoms occur suddenly and may include muscle weakness, paralysis, lost or abnormal sensation on one side of the body, difficulty speaking, confusion, problems with vision, dizziness, and loss of balance and coordination.

Symptoms occur suddenly and may include muscle weakness, paralysis, lost or abnormal sensation on one side of the body, difficulty speaking, confusion, problems with vision, dizziness, and loss of balance and coordination.

Diagnosis is usually based on symptoms and results of a physical examination, imaging tests, and blood tests.

Diagnosis is usually based on symptoms and results of a physical examination, imaging tests, and blood tests.

Treatment may include drugs to break up blood clots or to make blood less likely to clot and surgery, followed by rehabilitation.

Treatment may include drugs to break up blood clots or to make blood less likely to clot and surgery, followed by rehabilitation.

About one third of people recover all or most of normal function after an ischemic stroke.

About one third of people recover all or most of normal function after an ischemic stroke.

Causes

An ischemic stroke typically results from blockage of an artery that supplies the brain, most commonly a branch of one of the internal carotid arteries.

Commonly, blockages are blood clots (thrombi) or pieces of fatty deposits (atheromas, or plaques) due to atherosclerosis. Such blockages often occur in the following ways:

By forming in and blocking an artery: An atheroma in the wall of an artery may accumulate more fatty material and become large enough to block the artery. Or a blood clot can form and block the artery when an atheroma ruptures (see art on page 397). Clots tend to form on a ruptured atheroma because the atheroma narrows the artery and slows blood flow through it, like a clogged pipe slows the flow of water. Slow-moving blood is more likely to clot. A large clot can block enough blood flowing through the narrowed artery that brain cells supplied by that artery die.

By forming in and blocking an artery: An atheroma in the wall of an artery may accumulate more fatty material and become large enough to block the artery. Or a blood clot can form and block the artery when an atheroma ruptures (see art on page 397). Clots tend to form on a ruptured atheroma because the atheroma narrows the artery and slows blood flow through it, like a clogged pipe slows the flow of water. Slow-moving blood is more likely to clot. A large clot can block enough blood flowing through the narrowed artery that brain cells supplied by that artery die.

By traveling to another artery: A blood clot in the heart, a piece of an atheroma, or a blood clot in the wall of an artery can break off and travel through the bloodstream (becoming an embolus). The embolus may then lodge in an artery that supplies the brain and block blood flow there. (Embolism refers to blockage of arteries by materials that travel through the bloodstream to another part of the body.) Such blockages are more likely to occur where arteries are already narrowed by fatty deposits.

By traveling to another artery: A blood clot in the heart, a piece of an atheroma, or a blood clot in the wall of an artery can break off and travel through the bloodstream (becoming an embolus). The embolus may then lodge in an artery that supplies the brain and block blood flow there. (Embolism refers to blockage of arteries by materials that travel through the bloodstream to another part of the body.) Such blockages are more likely to occur where arteries are already narrowed by fatty deposits.

Several conditions besides rupture of an atheroma can trigger or promote the formation of blood clots, increasing the risk of blockage by a blood clot, such as the following:

Heart-related problems: Blood clots may form in the heart or on a heart valve (including artificial valves). Strokes due to such blood clots are most common among people who have recently had heart surgery and people who have a heart valve disorder or an abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia), especially a fast, irregular heart rhythm called atrial fibrillation.

Heart-related problems: Blood clots may form in the heart or on a heart valve (including artificial valves). Strokes due to such blood clots are most common among people who have recently had heart surgery and people who have a heart valve disorder or an abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia), especially a fast, irregular heart rhythm called atrial fibrillation.

Blood disorders: Some disorders, such as an excess of red blood cells (polycythemia), make blood thick, increasing the risk of blood clots. Some disorders, such as antiphospholipid syndrome and a high homocysteine level in the blood (hyperhomocysteinemia), make blood more likely to clot.

Blood disorders: Some disorders, such as an excess of red blood cells (polycythemia), make blood thick, increasing the risk of blood clots. Some disorders, such as antiphospholipid syndrome and a high homocysteine level in the blood (hyperhomocysteinemia), make blood more likely to clot.

Oral contraceptives: Taking oral contraceptives, particularly those with a high estrogen dose, increases the risk of blood clots.

Oral contraceptives: Taking oral contraceptives, particularly those with a high estrogen dose, increases the risk of blood clots.

Another common cause of ischemic strokes is a lacunar infarction. In lacunar infarction, one of the small arteries deep in the brain becomes blocked by a mixture of fat and connective tissue—a blood clot is not the cause. This disorder is called lipohyalinosis and tends to occur in older people with diabetes or poorly controlled high blood pressure. Lipohyalinosis is different from atherosclerosis, but both disorders can cause blockage of arteries. Only a small part of the brain is damaged in lacunar infarction.

Rarely, small pieces of fat from the marrow of a broken long bone, such as a leg bone, are released into the bloodstream. These pieces can clump together and block an artery. The resulting disorder, called fat embolism syndrome, may resemble a stroke.

An ischemic stroke can also result from any disorder that reduces the amount of blood or oxygen supplied to the brain, such as severe blood loss or very low blood pressure. Occasionally, an ischemic stroke occurs when blood flow to the brain is normal but the blood does not contain enough oxygen. Disorders that reduce the oxygen content of blood include a severe deficiency of red blood cells (anemia), suffocation, and carbon monoxide poisoning. Usually, brain damage in such cases is widespread (diffuse), and coma results.

An ischemic stroke can occur if inflammation of blood vessels (vasculitis) or infection (such as herpes simplex) narrows blood vessels that supply the brain. Migraine headaches or drugs such as cocaine and amphetamines can cause spasm of the arteries, which can narrow the arteries supplying the brain and cause a stroke.

Symptoms

Usually, symptoms occur suddenly and are often most severe a few minutes after they start because most ischemic strokes begin suddenly, develop rapidly, and cause death of brain tissue within minutes to hours. Then, most strokes become stable, causing little or no further damage. Strokes that remain stable for 2 to 3 days are called completed strokes. Sudden blockage by an embolus is most likely to cause this kind of stroke.

Less commonly, symptoms develop slowly. They result from strokes that continue to worsen for several hours to a day or two, as a steadily enlarging area of brain tissue dies. Such strokes are called evolving strokes. The progression of symptoms and damage is usually interrupted by somewhat stable periods, during which the area temporarily stops enlarging or some improvement occurs. Such strokes are usually due to the formation of clots in a narrowed artery.

Many different symptoms can occur, depending on which artery is blocked and thus which part of the brain is deprived of blood and oxygen (see page 677). When the arteries that branch from the internal carotid artery (which carry blood along the front of the neck to the brain) are affected, the following are most common:

Blindness in one eye

Blindness in one eye

Inability to see out of the same side in both eyes

Inability to see out of the same side in both eyes

Abnormal sensations, weakness, or paralysis in one arm or leg or on one side of the body

Abnormal sensations, weakness, or paralysis in one arm or leg or on one side of the body

When the arteries that branch from the vertebral arteries (which carry blood along the back of the neck to the brain) are affected, the following are most common:

Dizziness and vertigo

Dizziness and vertigo

Double vision

Double vision

Generalized weakness on both sides of the body

Generalized weakness on both sides of the body

Many other symptoms, such as difficulty speaking (for example, slurred speech), impaired consciousness (such as confusion), loss of coordination, and urinary incontinence, can occur.

Severe strokes may lead to stupor or coma. In addition, strokes, even milder ones, can cause depression or an inability to control emotions. For example, people may cry or laugh inappropriately.

If symptoms, particularly impaired consciousness, worsen during the first 2 to 3 days, the cause is often swelling due to excess fluid (edema) in the brain. Symptoms usually lessen within a few days, as the fluid is absorbed. Nonetheless, the swelling is particularly dangerous because the skull does not expand. The resulting increase in pressure can cause the brain to shift, further impairing brain function, even if the area directly damaged by the stroke does not enlarge. If the pressure becomes very high, the brain may be forced downward in the skull, through the rigid structures that separate the brain into compartments. The resulting disorder is called herniation (see art on page 735).

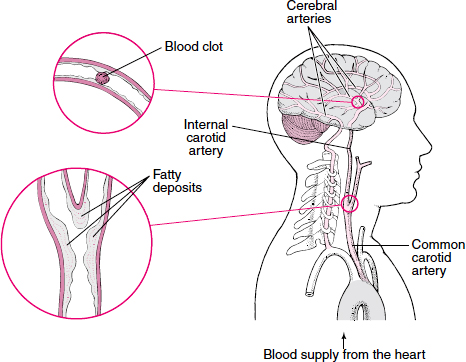

Clots: Causes of Ischemic Stroke

When an artery that carries blood to the brain becomes clogged or blocked, an ischemic stroke can occur. Arteries may be blocked by fatty deposits (atheromas, or plaques) due to atherosclerosis. Arteries in the neck, particularly the internal carotid arteries, are a common site for atheromas. Arteries may also be blocked by a blood clot (thrombus). Blood clots may form on an atheroma in an artery. Clots may also form in the heart of people with a heart disorder. Part of a clot may break off and travel through the bloodstream (becoming an embolus). It may then block an artery that supplies blood to the brain, such as one of the cerebral arteries.

Strokes can lead to other problems. If swallowing is difficult, people may not eat enough and become malnourished. Food, saliva, or vomit may be inhaled (aspirated) into the lungs, resulting in aspiration pneumonia. Being in one position too long can result in pressure sores and lead to muscle loss. Not being able to move the legs can result in the formation of blood clots in deep veins of the legs and groin (deep vein thrombosis). Clots can break off, travel through the bloodstream, and block an artery to a lung (a disorder called pulmonary embolism). People may have difficulty sleeping. The losses and problems resulting from the stroke may make people depressed.

Diagnosis

Doctors can usually diagnose an ischemic stroke based on the history of events and results of a physical examination. Doctors can usually identify which artery in the brain is blocked based on symptoms (see art on page 678). For example, weakness or paralysis of the left leg suggests blockage of the artery supplying the area on the right side of the brain that controls the left leg’s muscle movements.

Computed tomography (CT) is usually done first. CT helps distinguish an ischemic stroke from a hemorrhagic stroke, a brain tumor, an abscess, and other structural abnormalities. Doctors also measure the blood sugar level to rule out a low blood sugar level (hypoglycemia), which can cause similar symptoms. If available, diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which can detect ischemic strokes within minutes of their start, may be done next.

Identifying the precise cause of the stroke is important. If the blockage is a blood clot, another stroke is very likely unless the underlying disorder is corrected. For example, if blood clots result from an abnormal heart rhythm, treating that disorder can prevent new clots from forming and causing another stroke. Tests for causes may include the following:

Electrocardiography (ECG) to look for abnormal heart rhythms

Electrocardiography (ECG) to look for abnormal heart rhythms

Continuous ECG monitoring (done at home or in the hospital—see page 327) to record the heart rate and rhythm continuously for 24 hours (or more), which may detect abnormal heart rhythms that occur unpredictably or briefly

Continuous ECG monitoring (done at home or in the hospital—see page 327) to record the heart rate and rhythm continuously for 24 hours (or more), which may detect abnormal heart rhythms that occur unpredictably or briefly

Echocardiography to check the heart for blood clots, pumping or structural abnormalities, and valve disorders

Echocardiography to check the heart for blood clots, pumping or structural abnormalities, and valve disorders

Imaging tests—color Doppler ultrasonography, magnetic resonance angiography, CT angiography, or cerebral (standard) angiography—to determine whether arteries, especially the internal carotid arteries, are blocked or narrowed

Imaging tests—color Doppler ultrasonography, magnetic resonance angiography, CT angiography, or cerebral (standard) angiography—to determine whether arteries, especially the internal carotid arteries, are blocked or narrowed

Blood tests to check for anemia, polycythemia, blood clotting disorders, vasculitis, and some infections (such as heart valve infections and syphilis) and for risk factors such as high cholesterol levels or diabetes

Blood tests to check for anemia, polycythemia, blood clotting disorders, vasculitis, and some infections (such as heart valve infections and syphilis) and for risk factors such as high cholesterol levels or diabetes

Imaging tests enable doctors to determine how narrowed the carotid arteries are and thus to estimate the risk of a subsequent stroke or TIA. Such information helps determine which treatments are needed.

For cerebral angiography, a thin, flexible tube (catheter) is inserted into an artery, usually in the groin, and threaded through the aorta to an artery in the neck (see page 2036). Then, a dye is injected to outline the artery. Thus, this test is more invasive than other tests that provide images of the brain’s blood supply. However, it provides more information. Cerebral angiography may be done before atheromas are removed surgically or when vasculitis is suspected.

Rarely, a spinal tap (lumbar puncture) is done—for example, after CT, when doctors still need to determine whether strokelike symptoms are due to an infection or whether a subarachnoid hemorrhage is present (see page 731). This procedure is done only if doctors are sure that the brain is not under excess pressure (usually determined by CT or MRI).

Prognosis

About 10% of people who have an ischemic stroke recover almost all normal function, and about 25% recover most of it. About 40% of people have moderate to severe impairments requiring special care, and about 10% require care in a nursing home or other long-term care facility. Some people are physically and mentally devastated and unable to move, speak, or eat normally. About 20% of people who have a stroke die in the hospital. The proportion is higher among older people. About 25% of people who recover from a stroke have another stroke within 5 years. Subsequent strokes impair function further.

During the first few days after an ischemic stroke, doctors usually cannot predict whether a person will improve or worsen. Younger people and people who start improving quickly are likely to recover more fully. About 50% of people with one-sided paralysis and most of those with less severe symptoms recover some function by the time they leave the hospital, and they can eventually take care of their basic needs. They can think clearly and walk adequately, although use of the affected arm or leg may be limited. Use of an arm is more often limited than use of a leg. Most impairments still present after 12 months are permanent.

Treatment

People who have any symptom suggesting an ischemic stroke should go to an emergency department immediately. The earlier the treatment, the better are the chances for recovery.

The first priority is to restore the person’s breathing, heart rate, blood pressure (if low), and temperature to normal. An intravenous line is inserted to provide drugs and fluids when needed. If the person has a fever, it may be lowered using acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or a cooling blanket. An increase in body temperature by even a few degrees can dramatically worsen brain damage due to an ischemic stroke. Generally, doctors do not immediately treat high blood pressure unless it is very high (over 220/120 mm Hg) because, when arteries are narrowed, blood pressure must be higher than normal to push enough blood through them to the brain. However, very high blood pressure can injure the heart, kidneys, and eyes and must be lowered.

If a stroke is very severe, drugs such as mannitol may be given to reduce swelling and the increased pressure in the brain. Some people need a ventilator to breathe adequately.

Specific treatment of stroke may include drugs to break up blood clots (thrombolytic drugs), drugs to make blood less likely to clot (antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulants), and surgery, followed by rehabilitation.

Thrombolytic (Fibrinolytic) Drugs: In certain circumstances, a drug called tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is given intravenously to break up clots and help restore blood flow to the brain. Because tPA can cause bleeding in the brain and elsewhere, it should not be given to people with certain conditions, such as the following:

A past occurrence of a hemorrhagic stroke, a bulge (aneurysm) in an artery to the brain, other structural abnormalities in the brain, or a brain tumor

A past occurrence of a hemorrhagic stroke, a bulge (aneurysm) in an artery to the brain, other structural abnormalities in the brain, or a brain tumor

A seizure when the stroke began

A seizure when the stroke began

A tendency to bleed

A tendency to bleed

Recent major surgery

Recent major surgery

Recent bleeding (hemorrhage) in the gastrointestinal or urinary tract

Recent bleeding (hemorrhage) in the gastrointestinal or urinary tract

A recent head injury or other serious trauma

A recent head injury or other serious trauma

A very high or very low blood sugar level

A very high or very low blood sugar level

A heart infection

A heart infection

Current use of an anticoagulant (warfarin)

Current use of an anticoagulant (warfarin)

A large ischemic stroke

A large ischemic stroke

Blood pressure that remains high after treatment with an antihypertensive drug

Blood pressure that remains high after treatment with an antihypertensive drug

Symptoms that are resolving quickly

Symptoms that are resolving quickly

Before tPA is given, CT is done to rule out bleeding in the brain. To be effective and safe, tPA, given intravenously, must be started within 3 hours of the beginning of an ischemic stroke. After 3 hours, most of the damage to the brain cannot be reversed, and the risk of bleeding outweighs the possible benefit of the drug. However, pinpointing when the stroke began may be difficult. So doctors assume that the stroke began the last time a person was known to be well. For example, if a person awakens with symptoms of a stroke, doctors assume the stroke began when the person was last seen awake and well. Thus, tPA can be used in only a few people who have had a stroke.

If people arrive at the hospital 3 to 6 hours (occasionally, up to 18 hours) after the stroke began, they may be given tPA or another thrombolytic drug. But the drug must be given through a catheter instead. For this treatment, doctors make an incision in the skin, usually in the groin, and insert a catheter into an artery. The catheter is then threaded through the aorta and other arteries, to the clot. The clot is partly broken up with the catheter wire and then injected with tPA. This treatment is usually available only at specialized stroke centers.

Antiplatelet Drugs and Anticoagulants: If a thrombolytic drug cannot be used, most people are given aspirin (an antiplatelet drug) as soon as they get to the hospital. If symptoms seem to be worsening, anticoagulants such as heparin are occasionally used, but their effectiveness has not been proved. Antiplatelet drugs make platelets less likely to clump and form clots. Anticoagulants inhibit proteins in blood that help it to clot (clotting factors).

Regardless of the initial treatment, long-term treatment usually consists of aspirin or another antiplatelet drug to reduce the risk of blood clots and thus of subsequent strokes (see page 721). People who have atrial fibrillation or a heart valve disorder are given anticoagulants (such as warfarin) instead of antiplatelet drugs, which do not seem to prevent blood clots from forming in the heart. Occasionally, people at high risk of another stroke are given both aspirin and warfarin.

If people have been given a thrombolytic drug, doctors usually wait at least 24 hours before anti-platelet drugs or anticoagulants are started because these drugs add to the already increased risk of bleeding in the brain. Anticoagulants are not given to people who have uncontrolled high blood pressure or who have had a hemorrhagic stroke.

Surgery: Once an ischemic stroke is completed, surgical removal of atheromas or clots (endarterectomy) in an internal carotid artery may be done. Carotid endarterectomy can help if all of the following are present:

The stroke resulted from narrowing of a carotid artery by more than 70%.

The stroke resulted from narrowing of a carotid artery by more than 70%.

Some brain tissue supplied by the affected artery still functions after the stroke.

Some brain tissue supplied by the affected artery still functions after the stroke.

The person’s life expectancy is at least 5 years.

The person’s life expectancy is at least 5 years.

In such people, carotid endarterectomy may reduce the risk of subsequent strokes. It also reestablishes the blood supply to the affected area, but it cannot restore lost function because some brain tissue is dead.

For carotid endarterectomy, a general anesthetic or a local anesthetic (to numb the neck area) may be used. If people remain awake during the operation, the surgeon can better evaluate how the brain is functioning. The surgeon makes an incision in the neck over the area of the artery that contains the blockage and an incision in the artery. The blockage is removed, and the incisions are closed. For a few days afterwards, the neck may hurt, and swallowing may be difficult. Most people can stay in the hospital 1 or 2 days. Heavy lifting should be avoided for about 3 weeks. After several weeks, people can resume their usual activities.

Carotid endarterectomy can trigger a stroke because the operation may dislodge clots or other material that can then travel through the bloodstream and block an artery. However, after the operation, the risk of stroke is lower for several years than it is when drugs are used.

In other narrowed arteries, such as the vertebral arteries, endarterectomy may not be possible because the operation is riskier to perform in these arteries than in the internal carotid arteries.

People should find a surgeon who is experienced doing this operation and who has a low rate of serious complications (such as heart attack, stroke, and death) after the operation. If people cannot find such a surgeon, the risks of endarterectomy outweigh its expected benefits.

Stents: If endarterectomy is too risky, a less invasive procedure can be done: A wire mesh tube (stent) with an umbrella filter may be placed in the carotid artery. The stent helps keep the artery open, and the filter catches blood clots and prevents them from reaching the brain and causing a stroke. The filter is similar to one used to prevent pulmonary embolism (see art on page 436). After a local anesthetic is given, a catheter is inserted through a small incision into a large artery near the groin or in the arm and is threaded to the internal carotid artery in the neck. A dye that can be seen on x-rays (radiopaque dye) is injected, and x-rays are taken so that the narrowed area can be located. After the stent and filter are placed, the catheter is removed. People remain awake for the procedure, which usually takes 1 to 2 hours. The procedure appears to be as safe as endarterectomy and is almost as effective in preventing strokes and death.

Other Treatments: Another option being studied is a tiny corkscrew-shaped device that is attached to a catheter, threaded to the clot, and used to snag the clot. The clot is then drawn out through the catheter. This treatment may be useful for people who cannot be given tPA.

Treatment of Problems Due to Strokes: Measures to prevent aspiration pneumonia (see page 471) and pressure sores (see page 1299) are started early. Heparin, injected under the skin, may be given to help prevent deep vein thrombosis (see page 433). People are closely monitored to determine whether the esophagus, bladder, and intestines are functioning. Often, other disorders such as heart failure, abnormal heart rhythms, and lung infections must be treated. High blood pressure is often treated after the stroke has been stabilized.

Because a stroke often causes mood changes, especially depression, family members or friends should inform the doctor if the person seems depressed. Depression can be treated with drug therapy and psychotherapy (see page 866).

Hemorrhagic Stroke

Hemorrhagic strokes include bleeding within the brain (intracerebral hemorrhage) and bleeding between the inner and outer layers of the tissue covering the brain (subarachnoid hemorrhage).

There are two main types of hemorrhagic strokes: intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Other disorders that involve bleeding inside the skull include epidural (see page 738) and subdural (see page 739) hematomas, which are usually caused by a head injury. These disorders cause different symptoms and are not considered strokes.

INTRACEREBRAL HEMORRHAGE

An intracerebral hemorrhage is bleeding within the brain.

Intracerebral hemorrhage usually results from chronic high blood pressure.

Intracerebral hemorrhage usually results from chronic high blood pressure.

The first symptom is often a severe headache.

The first symptom is often a severe headache.

Diagnosis is based on symptoms and results of a physical examination and imaging tests.

Diagnosis is based on symptoms and results of a physical examination and imaging tests.

Treatment may include vitamin K, transfusions, and, rarely, surgery to remove the accumulated blood.

Treatment may include vitamin K, transfusions, and, rarely, surgery to remove the accumulated blood.

Intracerebral hemorrhage accounts for about 10% of all strokes but for a much higher percentage of deaths due to stroke. Among people older than 60, intracerebral hemorrhage is more common than subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Causes

Intracerebral hemorrhage most often results when chronic high blood pressure weakens a small artery, causing it to burst. Using cocaine or amphetamines can cause temporary but very high blood pressure and hemorrhage. In some older people, an abnormal protein called amyloid accumulates in arteries of the brain. This accumulation (called amyloid angiopathy) weakens the arteries and can cause hemorrhage.

Less common causes include blood vessel abnormalities present at birth, injuries, tumors, inflammation of blood vessels (vasculitis), bleeding disorders, and use of anticoagulants in doses that are too high. Bleeding disorders and use of anticoagulants increase the risk of dying from an intracerebral hemorrhage.

Symptoms

An intracerebral hemorrhage begins abruptly. In about half of the people, it begins with a severe headache, often during activity. However, in older people, the headache may be mild or absent. Symptoms suggesting brain dysfunction develop and steadily worsen as the hemorrhage expands. Some symptoms, such as weakness, paralysis, loss of sensation, and numbness, often affect only one side of the body. People may be unable to speak or become confused. Vision may be impaired or lost. The eyes may point in different directions or become paralyzed. The pupils may become abnormally large or small. Nausea, vomiting, seizures, and loss of consciousness are common and may occur within seconds to minutes.

Burst and Breaks: Causes of Hemorrhagic Stroke

When blood vessels of the brain are weak, abnormal, or under unusual pressure, a hemorrhagic stroke can occur. In hemorrhagic strokes, bleeding may occur within the brain, as an intracerebral hemorrhage. Or bleeding may occur between the inner and middle layer of tissue covering the brain (in the subarachnoid space), as a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Diagnosis

Doctors can often diagnose intracerebral hemorrhages on the basis of symptoms and results of a physical examination. However, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also done. Both tests can help doctors distinguish a hemorrhagic stroke from an ischemic stroke. The tests can also show how much brain tissue has been damaged and whether pressure is increased in other areas of the brain. The blood sugar level is measured because a low blood sugar level can cause symptoms similar to those of stroke.

Prognosis

Intracerebral hemorrhage is more likely to be fatal than ischemic stroke. The hemorrhage is usually large and catastrophic, especially in people who have chronic high blood pressure. More than half of the people who have a large hemorrhage die within a few days. Those who survive usually recover consciousness and some brain function over time. However, most do not recover all lost brain function.

Treatment

Treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage differs from that of an ischemic stroke. Anticoagulants (such as heparin and warfarin), thrombolytic drugs, and antiplatelet drugs (such as aspirin) are not given because they make bleeding worse. If people who are taking an anticoagulant have a hemorrhagic stroke, they may need a treatment that helps blood clot such as

Vitamin K, usually given intravenously

Vitamin K, usually given intravenously

Transfusions of platelets

Transfusions of platelets

Transfusions of blood that has had blood cells and platelets removed (fresh frozen plasma)

Transfusions of blood that has had blood cells and platelets removed (fresh frozen plasma)

Intravenous administration of a synthetic product similar to the proteins in blood that help blood to clot (clotting factors)

Intravenous administration of a synthetic product similar to the proteins in blood that help blood to clot (clotting factors)

Surgery to remove the accumulated blood and relieve pressure within the skull, even if it may be life-saving, is rarely done because the operation itself can damage the brain. Also, removing the accumulated blood can trigger more bleeding, further damaging the brain and leading to severe disability. However, this operation may be effective for hemorrhage in the pituitary gland or in the cerebellum. In such cases, a good recovery is possible.

SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

A subarachnoid hemorrhage is bleeding into the space (subarachnoid space) between the inner layer (pia mater) and middle layer (arachnoid mater) of the tissue covering the brain (meninges).

The most common cause is rupture of a bulge (aneurysm) in an artery.

The most common cause is rupture of a bulge (aneurysm) in an artery.

Usually, rupture of an artery causes a sudden, severe headache, often followed by a brief loss of consciousness.

Usually, rupture of an artery causes a sudden, severe headache, often followed by a brief loss of consciousness.

Computed tomography, sometimes a spinal tap, and angiography are done to confirm the diagnosis.

Computed tomography, sometimes a spinal tap, and angiography are done to confirm the diagnosis.

Drugs are used to relieve the headache and to control blood pressure, and surgery is done to stop the bleeding.

Drugs are used to relieve the headache and to control blood pressure, and surgery is done to stop the bleeding.

A subarachnoid hemorrhage is a life-threatening disorder that can rapidly result in serious, permanent disabilities. It is the only type of stroke more common among women than among men.

Causes

Subarachnoid hemorrhage usually results from head injuries. However, hemorrhage due to a head injury causes different symptoms and is not considered a stroke.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is considered a stroke only when it occurs spontaneously—that is, when the hemorrhage does not result from external forces, such as an accident or a fall. A spontaneous hemorrhage usually results from the sudden rupture of an aneurysm in a cerebral artery. Aneurysms are bulges in a weakened area of an artery’s wall. Aneurysms typically occur where an artery branches. Aneurysms may be present at birth (congenital), or they may develop later, after years of high blood pressure weaken the walls of arteries. Most subarachnoid hemorrhages result from congenital aneurysms.

Less commonly, subarachnoid hemorrhage results from rupture of an abnormal connection between arteries and veins (arteriovenous malformation) in or around the brain. An arteriovenous malformation may be present at birth, but it is usually identified only if symptoms develop. Rarely, a blood clot forms on an infected heart valve, travels (becoming an embolus) to an artery that supplies the brain, and causes the artery to become inflamed. The artery may then weaken and rupture.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Almost half of people with a subarachnoid hemorrhage die before reaching the hospital.

Symptoms

Before rupturing, an aneurysm usually causes no symptoms unless it presses on a nerve or leaks small amounts of blood, usually before a large rupture (which causes headache). Then it produces warning signs, such as the following:

Headache, which may be unusually sudden and severe (sometimes called a thunderclap headache)

Headache, which may be unusually sudden and severe (sometimes called a thunderclap headache)

Facial or eye pain

Facial or eye pain

Double vision

Double vision

Loss of peripheral vision

Loss of peripheral vision

The warning signs can occur minutes to weeks before the rupture. People should report any unusual headaches to a doctor immediately.

A rupture usually causes a sudden, severe headache that peaks within seconds. It is often followed by a brief loss of consciousness. Almost half of affected people die before reaching a hospital. Some people remain in a coma or unconscious. Others wake up, feeling confused and sleepy. They may also feel restless. Within hours or even minutes, people may again become sleepy and confused. They may become unresponsive and difficult to arouse. Within 24 hours, blood and cerebrospinal fluid around the brain irritate the layers of tissue covering the brain (meninges), causing a stiff neck as well as continuing headaches, often with vomiting, dizziness, and low back pain. Frequent fluctuations in the heart rate and in the breathing rate often occur, sometimes accompanied by seizures.

About 25% of people have symptoms that indicate damage to a specific part of the brain, such as the following:

Weakness or paralysis on one side of the body (most common)

Weakness or paralysis on one side of the body (most common)

Loss of sensation on one side of the body

Loss of sensation on one side of the body

Difficulty understanding and using language (aphasia—see page 679)

Difficulty understanding and using language (aphasia—see page 679)

Severe impairments may develop and become permanent within minutes or hours. Fever is common during the first 5 to 10 days.

A subarachnoid hemorrhage can lead to several other serious problems:

Hydrocephalus: Within 24 hours, the blood from a subarachnoid hemorrhage may clot. The clotted blood may prevent the fluid surrounding the brain (cerebrospinal fluid) from draining as it normally does. As a result, blood accumulates within the brain, increasing pressure within the skull. Hydrocephalus may contribute to symptoms such as headaches, sleepiness, confusion, nausea, and vomiting and may increase the risk of coma and death.

Hydrocephalus: Within 24 hours, the blood from a subarachnoid hemorrhage may clot. The clotted blood may prevent the fluid surrounding the brain (cerebrospinal fluid) from draining as it normally does. As a result, blood accumulates within the brain, increasing pressure within the skull. Hydrocephalus may contribute to symptoms such as headaches, sleepiness, confusion, nausea, and vomiting and may increase the risk of coma and death.

Vasospasm: About 3 to 10 days after the hemorrhage, arteries in the brain may contract (spasm), limiting blood flow to the brain. Then, brain tissues may not get enough oxygen and may die, as in ischemic stroke. Vasospasm may cause symptoms similar to those of ischemic stroke, such as weakness or loss of sensation on one side of the body, difficulty using or understanding language, vertigo, and impaired coordination.

Vasospasm: About 3 to 10 days after the hemorrhage, arteries in the brain may contract (spasm), limiting blood flow to the brain. Then, brain tissues may not get enough oxygen and may die, as in ischemic stroke. Vasospasm may cause symptoms similar to those of ischemic stroke, such as weakness or loss of sensation on one side of the body, difficulty using or understanding language, vertigo, and impaired coordination.

A second rupture: Sometimes a second rupture occurs, usually within a week.

A second rupture: Sometimes a second rupture occurs, usually within a week.

Diagnosis

If people have a sudden, severe headache that peaks within seconds or that is accompanied by any symptoms suggesting a stroke, they should go immediately to the hospital. Computed tomography (CT—see page 2037) is done to check for bleeding. A spinal tap (lumbar puncture—see page 635) is done if CT is inconclusive or unavailable. It can detect any blood in the cerebrospinal fluid. A spinal tap is not done if doctors suspect that pressure within the skull is increased. Cerebral angiography (see page 2036) is done as soon as possible to confirm the diagnosis and to identify the site of the aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation causing the bleeding. Magnetic resonance angiography (see page 2041) or CT angiography (see page 2038) may be used instead.

Prognosis

About 35% of people die when they have a subarachnoid hemorrhage due to an aneurysm because it results in extensive brain damage. Another 15% die within a few weeks because of bleeding from a second rupture. People who survive for 6 months but who do not have surgery for the aneurysm have a 3% chance of another rupture each year. The outlook is better when the cause is an arteriovenous malformation. Occasionally, the hemorrhage is caused by a small defect that is not detected by cerebral angiography because the defect has already sealed itself off. In such cases, the outlook is very good.

SPOTLIGHT ON AGING

After a stroke, older people are more likely to have problems, such as pressure sores, pneumonia, permanently shortened muscles (contractures) that limit movement, and depression. Older people are also more likely to already have disorders that limit treatment of stroke. For example, they may have very high blood pressure or gastrointestinal bleeding that prevents them from taking anticoagulants to reduce the risk of blood clots. Some treatments, such as endarterectomy, are more likely to cause complications in older people. Nonetheless, treatment decisions should be based on the person’s health rather than on age itself.

After a stroke, older people are more likely to have problems, such as pressure sores, pneumonia, permanently shortened muscles (contractures) that limit movement, and depression. Older people are also more likely to already have disorders that limit treatment of stroke. For example, they may have very high blood pressure or gastrointestinal bleeding that prevents them from taking anticoagulants to reduce the risk of blood clots. Some treatments, such as endarterectomy, are more likely to cause complications in older people. Nonetheless, treatment decisions should be based on the person’s health rather than on age itself.

Some disorders common among older people can interfere with their recovery after a stroke, as in the following:

People with dementia may not understand what is required of them for rehabilitation.

People with dementia may not understand what is required of them for rehabilitation.

People with heart failure or another heart disorder may risk having another stroke or a heart attack triggered by exertion during rehabilitation exercises.

People with heart failure or another heart disorder may risk having another stroke or a heart attack triggered by exertion during rehabilitation exercises.

A good recovery is more likely when older people have a family member or caregiver to help, a living situation that facilitates independence (for example, a first-floor residence and nearby shops), and financial resources to pay for rehabilitation.

Because recovery after stroke depends on so many medical, social, financial, and lifestyle factors, rehabilitation and care for older people should be individually designed and managed by a team of health care practitioners (including nurses, psychologists, and social workers as well as a doctor or therapist). Team members can also provide information about resources and strategies to help people who have had a stroke and their caregivers with daily living.

Some people recover most or all mental and physical function after a subarachnoid hemorrhage. However, many people continue to have symptoms such as weakness, paralysis, or loss of sensation on one side of the body or aphasia.

Treatment

People who may have had a subarachnoid hemorrhage are hospitalized immediately. Bed rest with no exertion is essential. Analgesics such as opioids (but not aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which can worsen the bleeding) are given to control the severe headaches. Stool softeners are given to prevent straining during bowel movements. Nimodipine, a calcium channel blocker, is usually given by mouth to prevent vasospasm and subsequent ischemic stroke. Doctors take measures (such as giving drugs and adjusting the amount of intravenous fluid given) to keep blood pressure at levels low enough to avoid further hemorrhage and high enough to maintain blood flow to the damaged parts of the brain. Occasionally, a piece of plastic tubing (shunt) may be placed in the brain to drain cerebrospinal fluid away from the brain. This procedure relieves pressure and prevents hydrocephalus.

For people who have an aneurysm, a surgical procedure is done to isolate, block off, or support the walls of the weak artery and thus reduce the risk of fatal bleeding later. These procedures are difficult, and regardless of which one is used, the risk of death is high, especially for people who are in a stupor or coma. The best time for surgery is controversial and must be decided based on the person’s situation. Most neurosurgeons recommend operating within 24 hours of the start of symptoms, before hydrocephalus and vasospasm develop. If surgery cannot be done this quickly, the procedure may be delayed 10 days to reduce the risks of surgery, but then bleeding is more likely to recur because the waiting period is longer.

A commonly used procedure, called neuroendovascular surgery, involves inserting coiled wires into the aneurysm. The coils are placed using a catheter that is inserted into an artery and threaded to the aneurysm. Thus, this procedure does not require that the skull be opened. By slowing blood flow through the aneurysm, the coils promote clot formation, which seals off the aneurysm and prevents it from rupturing. Neuroendovascular surgery can often be done at the same time as cerebral angiography, when the aneurysm is diagnosed.

Less commonly, a metal clip is placed across the aneurysm. This procedure prevents blood from entering the aneurysm and eliminates the risk of rupture. The clip remains in place permanently. Most clips that were placed 15 to 20 years ago are affected by the magnetic forces and can be displaced during magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). People who have these clips should inform their doctor if MRI is being considered. Newer clips are not affected by the magnetic forces.