CHAPTER 121

Spinal Cord Disorders

Causes of spinal cord disorders include injuries, infections, a blocked blood supply, and compression by a fractured bone or a tumor.

Causes of spinal cord disorders include injuries, infections, a blocked blood supply, and compression by a fractured bone or a tumor.

Typically, muscles are weak or paralyzed, sensation is abnormal or lost, and controlling bladder and bowel function may be difficult.

Typically, muscles are weak or paralyzed, sensation is abnormal or lost, and controlling bladder and bowel function may be difficult.

Doctors base the diagnosis on symptoms and results of a physical examination and imaging tests, such as magnetic resonance imaging.

Doctors base the diagnosis on symptoms and results of a physical examination and imaging tests, such as magnetic resonance imaging.

The condition causing the spinal cord disorder is corrected if possible.

The condition causing the spinal cord disorder is corrected if possible.

Often, rehabilitation is needed to recover as much function as possible.

Often, rehabilitation is needed to recover as much function as possible.

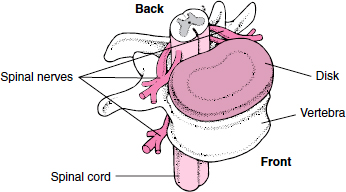

The spinal cord is the main pathway of communication between the brain and the rest of the body. It is a long, fragile, tubelike structure that extends downward from the base of the brain. The cord is protected by the back bones (vertebrae) of the spine (spinal column). The vertebrae are separated and cushioned by disks made of cartilage.

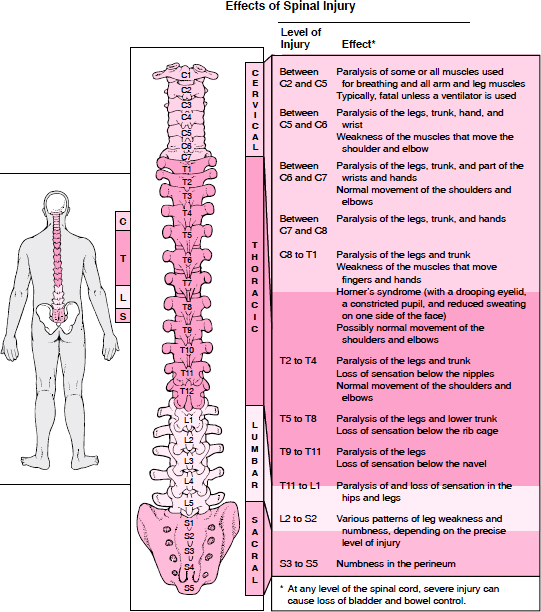

The spine is divided into four sections, and each section is referred to by a letter.

Cervical (C): Neck

Cervical (C): Neck

Thoracic (T): Chest

Thoracic (T): Chest

Lumbar (L): Lower back

Lumbar (L): Lower back

Sacral (S): Pelvis

Sacral (S): Pelvis

Within each section of the spine, the vertebrae are numbered beginning at the top. These labels (letter plus a number) are used to indicate locations (levels) in the spinal cord.

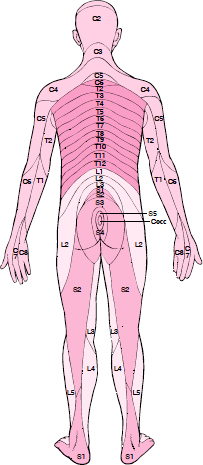

Along the length of the spinal cord, 31 pairs of spinal nerves emerge through spaces between the vertebrae. Each spinal nerve runs from a specific vertebra in the spinal cord to a specific area of the body. Based on this fact, the skin’s surface has been divided into areas called dermatomes. A dermatome is an area of skin whose sensory nerves all come from a single spinal nerve root. Loss of sensation in a particular dermatome enables doctors to locate where the spinal cord is damaged.

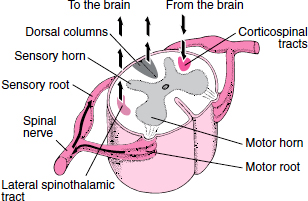

A spinal nerve has two nerve roots. The only exception is the first spinal nerve, which has no sensory root. The root in the front (the motor or anterior root) contains nerve fibers that carry impulses (signals) from the spinal cord to muscles to stimulate muscle movement (contraction). The root in the back (the sensory or posterior root) contains nerve fibers that carry sensory information about touch, position, pain, and temperature from the body to the spinal cord.

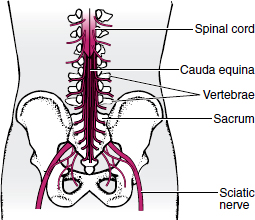

The spinal cord ends in the lower back (around L1 or L2), but the lower spinal nerve roots continue, forming a bundle that resembles a horse’s tail (called the cauda equina).

The spinal cord is highly organized (see art on page 626). The center of the cord consists of gray matter shaped like a butterfly. The front “wings” (anterior or motor horns) contain nerve cells that carry signals from the brain or spinal cord through the motor root to muscles. The back (posterior or sensory) horns contain nerve cells that receive signals about pain, temperature, and other sensory information through the sensory root from nerve cells outside the spinal cord.

The outer part of the spinal cord consists of white matter that contains pathways of nerve fibers (called tracts or columns). Each tract carries a specific type of nerve signal either going to the brain (ascending tracts) or from the brain (descending tracts).

Causes

Some spinal cord disorders originate outside the cord. They include injuries, most infections (see page 749), blockage of the blood supply, and compression. The spinal cord may be compressed by bone (which may result from cervical spondylosis or a fracture), an accumulation of blood (hematoma), a tumor, a localized collection of pus (abscess), or a ruptured or herniated disk.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Doctors can often tell where the spinal cord is damaged based on symptoms and results of a physical examination.

Less commonly, spinal cord disorders originate in the cord. They include fluid-filled cavities (syrinxes), inflammation (as occurs in acute transverse myelitis), tumors, abscesses, bleeding (hemorrhage), infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), multiple sclerosis, and syphilis.

Symptoms

Because of the way the spinal cord functions and is organized, damage to the cord often produces specific patterns of symptoms based on where the damage occurred. The following may occur in various patterns:

Where Is the Spinal Cord Damaged?

The spine (spinal column) contains the spinal cord, which is divided into four sections: cervical (neck), thoracic (chest), lumbar (lower back), and sacral (pelvis). Each section is referred to by a letter (C, T, L, or S). The vertebrae in each section of the spine are numbered beginning at the top. For example, the first vertebra in the cervical spine is labeled C1, the second in the cervical spine is C2, the second in the thoracic spine is T2, the fourth in the lumbar spine is L4, and so forth. These labels are also used to identify specific locations (called levels) in the spinal cord.

Nerves run from a specific level of the spinal cord to a specific area of the body. By noting where a person has weakness, paralysis, sensory loss, or other loss of function, a neurologist can determine where the spinal cord is damaged.

Weakness

Weakness

Loss of sensation (such as the ability to feel a light touch, pain, temperature, or vibration)

Loss of sensation (such as the ability to feel a light touch, pain, temperature, or vibration)

Changes in reflexes

Changes in reflexes

Loss of bladder control (urinary incontinence)

Loss of bladder control (urinary incontinence)

Loss of bowel control (fecal incontinence)

Loss of bowel control (fecal incontinence)

Erectile dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction

Paralysis

Paralysis

Back pain

Back pain

By identifying which functions are lost, doctors can tell which part of the spinal cord (such as the front, back, or entire cord) is damaged. By identifying the specific location of symptoms (for example, which muscles are paralyzed and which parts of the body lack sensation), doctors can determine exactly where the spinal cord is damaged (that is, the specific level of damage).

Functions may be completely or partially lost. Functions controlled by areas above the damage are not affected.

When weakness or paralysis occurs, muscles often go limp (flaccid), losing their tone. But some disorders (such as injuries and hereditary spastic para-paresis) can cause paralysis with muscle spasms (called spastic paralysis). Spasms can occur because signals from the brain cannot pass through the damaged area to help control some reflexes. As a result, the reflexes become more pronounced over days to weeks. Then, the muscles controlled by the reflex may tighten, feel hard, and twitch uncontrollably from time to time.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Nerves from the lowest parts of the spinal cord go to the anus, not to the feet.

Diagnosis

Often, doctors can recognize a spinal cord disorder based on its characteristic pattern of symptoms. Doctors always do a physical examination, which provides clues to the diagnosis. An imaging test is done to confirm the diagnosis and determine the cause.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most accurate imaging test for spinal cord disorders. MRI shows the spinal cord, as well as abnormalities in the soft tissues around the cord (such as abscesses, hematomas, tumors, and ruptured disks) and in bone (such as tumors, fractures, and cervical spondylosis). If MRI is not available, myelography with computed tomography (CT) is used. For myelography, a radiopaque dye is injected into the fluid around the spinal cord, and x-rays are taken. It is not as accurate or as safe as MRI.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

People who suddenly lose sensation, experience weakness in one or more limbs, or develop incontinence should see a doctor immediately.

Treatment

If symptoms of spinal cord dysfunction (such as paralysis or loss of sensation) suddenly occur, people should see a doctor immediately. Sometimes doing so can prevent permanent nerve damage or paralysis. If possible, the cause is treated or corrected. However, such treatment is often impossible or unsuccessful.

People who are paralyzed or confined to bed because of a spinal cord disorder require skilled nursing care to prevent complications, which include the following:

Pressure sores: Nurses inspect the person’s skin daily, keep the skin dry and clean, and turn the person frequently (see page 1300). When necessary, a special bed called a Stryker frame is used. It can be turned to shift pressure on the body from front to back and from side to side.

Pressure sores: Nurses inspect the person’s skin daily, keep the skin dry and clean, and turn the person frequently (see page 1300). When necessary, a special bed called a Stryker frame is used. It can be turned to shift pressure on the body from front to back and from side to side.

Urinary problems: If a person is immobile and cannot use a toilet, a urinary catheter may be needed. To help reduce the risk of a urinary tract infection, nurses use sterile techniques when the catheter is inserted and apply antimicrobial ointments or solutions daily.

Urinary problems: If a person is immobile and cannot use a toilet, a urinary catheter may be needed. To help reduce the risk of a urinary tract infection, nurses use sterile techniques when the catheter is inserted and apply antimicrobial ointments or solutions daily.

Pneumonia: To reduce the risk of pneumonia, therapists and nurses may teach the person deep breathing exercises. They may also place the person at an angle to help drain secretions that accumulate in the lungs (postural drainage) or suction secretions out.

Pneumonia: To reduce the risk of pneumonia, therapists and nurses may teach the person deep breathing exercises. They may also place the person at an angle to help drain secretions that accumulate in the lungs (postural drainage) or suction secretions out.

Blood clots: Anticoagulant drugs, such as heparin or low molecular weight heparin, may be given by injection. If a person cannot take anticoagulants (for example, because of a bleeding disorder or stomach ulcers), a filter, sometimes called an umbrella (see art on page 436), is inserted into the inferior vena cava (the large vein that carries blood from the abdomen to the heart). The filter traps blood clots that have broken loose from leg veins before they reach the heart.

Blood clots: Anticoagulant drugs, such as heparin or low molecular weight heparin, may be given by injection. If a person cannot take anticoagulants (for example, because of a bleeding disorder or stomach ulcers), a filter, sometimes called an umbrella (see art on page 436), is inserted into the inferior vena cava (the large vein that carries blood from the abdomen to the heart). The filter traps blood clots that have broken loose from leg veins before they reach the heart.

Dermatomes

The surface of the skin is divided into specific areas, called dermatomes. A dermatome is an area of skin whose sensory nerves all come from a single spinal nerve root.

Spinal roots come in pairs—one of each pair on each side of the body. There are 8 pairs of sensory nerve roots for the 7 cervical vertebrae. Each of the 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, and 5 sacral vertebrae has one pair of spinal nerve roots. In addition, at the end of the spinal cord, there is a pair of coccygeal nerve roots, which supply a small area of the skin around the tailbone (coccyx). There are dermatomes for each of these nerve roots.

Sensory information from a specific dermatome is carried by sensory nerve fibers to the spinal nerve root of a specific vertebra. For example, sensory information from a strip of skin along the lower back, the outside of the thigh, the inside of the lower leg, and the heel is carried by sensory nerve fibers of the sciatic nerve to the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) nerve root.

Extensive loss of body functions can be devastating, causing depression and loss of self-esteem. Formal counseling can be very helpful. Learning exactly what has happened and what to expect in the near and distant future helps people cope with the loss and prepare them for rehabilitation.

Rehabilitation: Rehabilitation helps people recover as much function as possible. The best care is provided by a team that includes nurses, physical and occupational therapists (see page 53), a social worker, a nutritionist, a psychologist, and a counselor, as well as the person and family members. A nurse may teach the person ways to manage bladder and bowel dysfunction, such as how to insert a catheter, when to use laxatives, or how to stimulate bowel movements using a finger.

Physical therapy involves exercises for muscle strengthening and stretching. People may learn how to use assistive devices such as braces, a walker, or a wheelchair and how to manage muscle spasms. Occupational therapy helps people relearn how to do their daily tasks and helps them improve dexterity and coordination. They learn special techniques to help compensate for lost functions. Therapists or counselors help some people make the adjustments needed to return to work and to hobbies and activities. People are taught ways to deal with sexual dysfunction. Sex is still possible for many people, even though sensation is usually lost.

Emotional support from family members and close friends is important.

Injuries of the Spinal Cord and Vertebrae

Most spinal cord injuries result from motor vehicle accidents.

Most spinal cord injuries result from motor vehicle accidents.

Symptoms, such as loss of sensation and loss of muscle control, may be temporary or permanent.

Symptoms, such as loss of sensation and loss of muscle control, may be temporary or permanent.

Magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography is the best way to identify the injury.

Magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography is the best way to identify the injury.

Treatment involves immobilization of the spine, drugs to relieve symptoms, sometimes surgery, and usually rehabilitation.

Treatment involves immobilization of the spine, drugs to relieve symptoms, sometimes surgery, and usually rehabilitation.

Injuries may affect the spinal cord or the roots of the spinal nerves, which pass through the spaces between the back bones (vertebrae) of the spine. The bundle of nerves that extend downward from the spinal cord (cauda equina) may also be injured. Injuries of the spinal cord include the following:

Jarring by a blunt injury (such as a fall or a collision)

Jarring by a blunt injury (such as a fall or a collision)

Pressure (compression) by broken bones, swelling, or an accumulation of blood (hematoma)

Pressure (compression) by broken bones, swelling, or an accumulation of blood (hematoma)

Partial or complete tears (severing)

Partial or complete tears (severing)

To and From and Up and Down the Spinal Cord

Spinal nerves carry nerve impulses to and from the spinal cord through two nerve roots:

Motor (anterior) root: Located toward the front, this root carries impulses from the spinal cord to muscles to stimulate muscle movement.

Motor (anterior) root: Located toward the front, this root carries impulses from the spinal cord to muscles to stimulate muscle movement.

Sensory (posterior) root: Located toward the back, this root carries sensory information about touch, position, pain, and temperature from the body to the spinal cord.

Sensory (posterior) root: Located toward the back, this root carries sensory information about touch, position, pain, and temperature from the body to the spinal cord.

In the center of the spinal cord, a butterfly-shaped area of gray matter helps relay impulses to and from spinal nerves. Its “wings” are called horns.

Motor (anterior) horns: These horns contain nerve cells that carry signals from the brain or spinal cord through the motor root to muscles.

Motor (anterior) horns: These horns contain nerve cells that carry signals from the brain or spinal cord through the motor root to muscles.

Posterior (sensory) horns: These horns contain nerve cells that receive signals about pain, temperature, and other sensory information through the sensory root from nerve cells outside the spinal cord.

Posterior (sensory) horns: These horns contain nerve cells that receive signals about pain, temperature, and other sensory information through the sensory root from nerve cells outside the spinal cord.

Impulses travel up (to the brain) or down (from the brain) the spinal cord through distinct pathways (tracts). Each tract carries a different type of nerve signal either going to or from the brain. The following are examples:

Lateral spinothalamic tract: Signals about pain and temperature, received by the sensory horn, travel through this tract to the brain.

Lateral spinothalamic tract: Signals about pain and temperature, received by the sensory horn, travel through this tract to the brain.

Dorsal columns: Signals about the position of the arms and legs, received by the sensory horn, travel through these tracts to the brain.

Dorsal columns: Signals about the position of the arms and legs, received by the sensory horn, travel through these tracts to the brain.

Corticospinal tracts: Signals to move a muscle travel from the brain through these tracts to the motor horn, which routes them to the muscle.

Corticospinal tracts: Signals to move a muscle travel from the brain through these tracts to the motor horn, which routes them to the muscle.

Because the spinal cord is surrounded and protected by the spine, injuries of the spine or its connective tissue (such as disks and ligaments—see art on page 807) can also injure the spinal cord.

Such injuries include the following:

Fractures

Fractures

Complete separation (dislocation) of adjacent vertebrae

Complete separation (dislocation) of adjacent vertebrae

Partial misalignment (subluxation) of adjacent vertebrae

Partial misalignment (subluxation) of adjacent vertebrae

Loosened attachments (composed of connective tissue) between adjacent vertebrae

Loosened attachments (composed of connective tissue) between adjacent vertebrae

Attachments may be loosened so much that the vertebrae move freely. These injuries are considered unstable. When vertebrae move, they can compress the spinal cord or its blood supply and damage spinal nerve roots.

Most spinal cord injuries occur in motor vehicle accidents. Other causes include falls, sports, work-related accidents, and violence (such as a knife or gunshot wound).

Symptoms

If the spinal cord is injured, the nerves at and below the site of the injury malfunction, causing loss of muscle control and loss of sensation.

Loss of muscle control or sensation may be temporary or permanent, partial or total, depending on the severity of the injury. An injury that severs the cord or destroys nerve pathways in the spinal cord causes permanent loss, but a blunt injury that jars the cord may cause temporary loss, which can last days, weeks, or months. Sometimes swelling causes symptoms that suggest an injury more severe than it is, but the symptoms usually lessen as the swelling subsides.

Partial loss of muscle control results in muscle weakness. Paralysis usually refers to complete loss. When muscles are paralyzed, they often go limp (flaccid), losing their tone. But when the spinal cord is injured, paralysis may progress weeks later to involuntary, prolonged muscle spasms (called spastic paralysis).

If the spine is injured, people usually feel pain in the neck or back. The area over the injury may be tender to the touch. For people who are weak or paralyzed, movement is limited or impossible. Consequently, they are at risk of developing blood clots, pressure sores, permanently shortened muscles (contractures), urinary tract infections, and pneumonia.

Diagnosis

Spinal cord injuries are best diagnosed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Computed tomography (CT) is an alternative.

Injuries of the spine (affecting bone) are diagnosed most accurately with CT. However, x-rays are sometimes done first because they may be more readily available than CT.

Prognosis

Recovery is more likely if paralysis is partial and if movement or sensation starts to return during the first week after the injury. If function is not regained within 6 months, loss is likely to be permanent.

Treatment

People who may have a spinal cord injury should not be moved except by emergency personnel. The first goals are to make sure people can breathe and to prevent further damage. Thus, emergency personnel take great care when moving a person with a possible spinal cord injury. Usually, the person is strapped to a firm board and carefully padded to prevent movement. A rigid collar may be used to keep the neck from moving. When the spine is severely damaged, the vertebrae may no longer be held in place or may be broken, making the spine unstable. Thus, even slight movement of the injured person can cause the spine to shift, putting pressure on the spinal cord. Pressure on the cord increases the risk of permanent paralysis.

Surgery is needed to remove blood and bone fragments if they have accumulated around the spinal cord. If the spine is unstable, people are kept immobile until the bone and other tissues have had time to heal. Sometimes a surgeon implants steel rods to stabilize the spine so that it cannot move and cause additional injury. If an injury causes only partial loss of function, surgery done soon after the injury may enable people to recover more function and become mobile sooner. However, the best time for surgery is debated. Spinal surgery may be done by neurosurgeons or orthopedic surgeons.

Drugs may be useful.

Corticosteroids: If the injury is caused by a blunt force, doctors may immediately give corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone, by injection to help prevent swelling around the injury. The drugs must be started within 8 hours of the injury to be effective and should be continued for about 24 hours. However, not all doctors think corticosteroids are helpful because whether the benefit outweighs the risk of side effects is unclear.

Corticosteroids: If the injury is caused by a blunt force, doctors may immediately give corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone, by injection to help prevent swelling around the injury. The drugs must be started within 8 hours of the injury to be effective and should be continued for about 24 hours. However, not all doctors think corticosteroids are helpful because whether the benefit outweighs the risk of side effects is unclear.

Pain relievers (analgesics): If the injury causes pain, analgesics are given. During the first hours and days, opioids are usually used. Milder analgesics, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, may be used later.

Pain relievers (analgesics): If the injury causes pain, analgesics are given. During the first hours and days, opioids are usually used. Milder analgesics, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, may be used later.

Muscle relaxants: If muscle spasms develop, muscle relaxants, such as baclofen or tizanidine, may be used.

Muscle relaxants: If muscle spasms develop, muscle relaxants, such as baclofen or tizanidine, may be used.

Experimental treatments to stimulate growth of spinal nerves are being studied. For example, a certain type of white blood cell (macrophage) can be extracted from, then injected into the injured person. Experimental drugs can be injected into the space around the spinal cord (epidurally) or taken by mouth. Using stem cells is another possibility, but this treatment requires much more study.

Rehabilitation, including physical and occupational therapy, can help people recover more quickly or more completely (see page 53).

Compression of the Spinal Cord

Injuries and disorders can put pressure on the spinal cord, causing back pain, tingling, muscle weakness, and other symptoms.

The spinal cord may be compressed by bone, blood (hematomas), pus (abscesses), tumors, or a ruptured or herniated disk.

The spinal cord may be compressed by bone, blood (hematomas), pus (abscesses), tumors, or a ruptured or herniated disk.

Symptoms, such as back pain, abnormal sensations, muscle weakness, or impaired bladder and bowel control, may be mild or severe.

Symptoms, such as back pain, abnormal sensations, muscle weakness, or impaired bladder and bowel control, may be mild or severe.

Doctors base the diagnosis on symptoms and the results of a physical examination, magnetic resonance imaging, or another imaging test.

Doctors base the diagnosis on symptoms and the results of a physical examination, magnetic resonance imaging, or another imaging test.

Depending on the cause, surgery or a corticosteroid drug is used to relieve the pressure.

Depending on the cause, surgery or a corticosteroid drug is used to relieve the pressure.

Normally, the spinal cord is protected by the spine, but certain injuries and disorders may put pressure (compress) on the spinal cord, disrupting its normal function. These injuries and disorders may also compress the roots of spinal nerves, which pass through the spaces between the back bones (vertebrae), or the bundle of nerves that extend downward from the spinal cord (cauda equina).

The spinal cord may be compressed suddenly, causing symptoms in minutes or over a few hours or days, or slowly, causing symptoms that worsen over many weeks or months.

Causes

The spinal cord may be compressed by the following:

Bone: If the back bones (vertebrae) are broken (fractured), are dislocated, or grow abnormally (as occurs in cervical spondylosis), they may compress the spinal cord. Vertebrae that are weakened by cancer or osteoporosis may break after a slight or even no injury.

Bone: If the back bones (vertebrae) are broken (fractured), are dislocated, or grow abnormally (as occurs in cervical spondylosis), they may compress the spinal cord. Vertebrae that are weakened by cancer or osteoporosis may break after a slight or even no injury.

Connective tissue: Connective tissue, such as ligaments, can compress the spinal cord after a severe spinal injury.

Connective tissue: Connective tissue, such as ligaments, can compress the spinal cord after a severe spinal injury.

An accumulation of blood (hematoma): Blood may accumulate in or around the spinal cord. The most common cause of a spinal hematoma is an injury, but many other conditions can cause hematomas. They include abnormal connections between blood vessels (arteriovenous malformations), tumors, bleeding disorders, and use of anticoagulants (which interfere with blood clotting) or thrombolytic drugs (which break up blood clots).

An accumulation of blood (hematoma): Blood may accumulate in or around the spinal cord. The most common cause of a spinal hematoma is an injury, but many other conditions can cause hematomas. They include abnormal connections between blood vessels (arteriovenous malformations), tumors, bleeding disorders, and use of anticoagulants (which interfere with blood clotting) or thrombolytic drugs (which break up blood clots).

Tumors: Cancer that has spread (metastasized) to the spine or the space around the spinal cord is a common cause of compression. Rarely, a tumor within the spine causes compression.

Tumors: Cancer that has spread (metastasized) to the spine or the space around the spinal cord is a common cause of compression. Rarely, a tumor within the spine causes compression.

A localized collection of pus (abscess): Less commonly, pus accumulates in or around the spinal cord and compresses it.

A localized collection of pus (abscess): Less commonly, pus accumulates in or around the spinal cord and compresses it.

A ruptured or herniated disk: A herniated disk can compress spinal nerve roots (the part of spinal nerves next to the spinal cord) and occasionally the spinal cord itself.

A ruptured or herniated disk: A herniated disk can compress spinal nerve roots (the part of spinal nerves next to the spinal cord) and occasionally the spinal cord itself.

Sometimes the cauda equina syndrome results in compression of the spinal cord.

Sudden compression usually results from an injury, which often causes a fracture or dislocation of a vertebra. Gradual compression may result from cancer or cervical spondylosis, but bones weakened gradually (for example, by cancer or osteoporosis) may suddenly fracture, which can suddenly worsen compression. Hematomas, abscesses, and ruptured disks can cause sudden compression but often cause compression gradually over days to weeks. The most common cause of slowly developing compression (over months to years) is cervical spondylosis (degeneration of disks and vertebrae in the neck—see page 801).

Symptoms

Slight compression may cause mild symptoms if it disrupts only some nerve impulses going up and down the spinal cord. These symptoms may include discomfort or pain in the back, slight muscle weakness, tingling, other changes in sensation, and, in men, difficulty initiating and maintaining an erection (erectile dysfunction). Pain may radiate down a leg, sometimes to the foot. If the cause is cancer, an abscess, or a hematoma, the back may be tender to the touch in the affected area. Sometimes sensation is lost. Reflexes, including the urge to urinate, may be exaggerated, sometimes causing muscle spasms and increased sweating. If compression increases, symptoms may worsen.

What Is the Cauda Equina Syndrome?

A bundle of nerves extends downward from the bottom of the spinal cord, through the lower vertebrae and over the sacrum (the bone at the base of the spine). This bundle is called the cauda equina, which means horse’s tail in Latin, because that is what the bundle looks like. The cauda equina may be compressed by a ruptured or herniated disk, a tumor, an abscess, damage due to an injury, or swelling due to inflammation (as occurs in ankylosing spondylitis). The symptoms that result are called the cauda equina syndrome.

Pain is felt in the lower back, but sensation is reduced in the buttocks, thighs, bladder, and rectum—the area of the body that would touch a saddle. Thus, this condition is called saddle anesthesia. Sensation and muscle control may be impaired in the lower legs. Other symptoms may occur:

Reduced sexual response, including erectile dysfunction in men

Reduced sexual response, including erectile dysfunction in men

Retention of urine

Retention of urine

Loss of bladder control (urinary incontinence)

Loss of bladder control (urinary incontinence)

Loss of bowel control (fecal incontinence)

Loss of bowel control (fecal incontinence)

Loss of reflexes in the ankle

Loss of reflexes in the ankle

People who have the cauda equina syndrome require immediate medical attention. Surgery to relieve the compression must be done as soon as possible. Corticosteroids may be given to reduce swelling.

Substantial compression may block most nerve impulses, causing severe muscle weakness, numbness, retention of urine, and loss of bladder and bowel control. If all nerve impulses are blocked, paralysis and complete loss of sensation result. A beltlike band of discomfort may be felt at the level of spinal cord compression. Once compression begins to cause symptoms, the damage usually worsens from minimal to substantial unpredictably but rapidly in a few hours to a few days.

Diagnosis

People with symptoms suggesting spinal cord compression require immediate medical attention because prompt diagnosis and treatment may reverse or lessen loss of function.

Because the spinal cord is organized in a specific way, doctors can determine which part of the spinal cord is affected based on the symptoms and results of a physical examination. For example, if the legs (but not the arms) are weak and numb and bladder and bowel functions are impaired, the spine may be damaged at the midchest (thoracic) level. The location of pain or tenderness along the spine also helps doctors determine the site of the damage.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is done immediately. Or if MRI is unavailable, myelography (x-ray of the spinal column after injection of a radiopaque dye) with computed tomography (CT) is done. These tests usually show where the spinal cord is compressed and may indicate the cause. MRI or myelography with CT can detect a fracture or dislocation of a vertebra, a herniated disk, an abnormal bone growth, an area of bleeding, an abscess, or a tumor. During myelography, a spinal tap (lumbar puncture) is done to inject a small amount of radiopaque dye into the space around the cord. Thus, doctors can determine whether compression completely blocks the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid through this space.

If the cause is thought to be a fracture or dislocation due to injury, x-rays may also be taken. They provide information quickly, enabling doctors to quickly evaluate the problem.

The cause of the compression is confirmed during surgery to relieve the pressure on the spinal cord.

If surgery is not done immediately and if MRI or myelography with CT detects an unidentifiable abnormal mass causing compression, a biopsy is done instead of surgery to identify it. Guided by CT, doctors insert a needle into the abnormal mass.

Treatment

If loss of function is partial or very recent (usually when compression occurs suddenly), the compression must be relieved immediately. When compression is detected and treated quickly, before nerve pathways are destroyed, treatment can prevent permanent damage to the spinal cord, and function is usually completely recovered. Surgery is typically needed to relieve compression. Surgery may also be needed to insert steel rods and thus stabilize the spine.

Other treatment varies depending on the cause.

For certain disorders, high doses of corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone or methylprednisolone, are given intravenously as soon as possible. These disorders include tumors if the cause is unknown and possibly blunt injuries. Corticosteroids can reduce swelling in or around the spinal cord, which may be contributing to compression. If an abscess causes symptoms of spinal cord dysfunction (such as paralysis and loss of bowel or bladder control), a neurosurgeon surgically removes the abscess as soon as possible. Antibiotics are also given. If symptoms of spinal cord dysfunction have not developed, drawing the pus out through a needle, giving antibiotics, or both may be all that is needed.

If the cause is a hematoma, the accumulated blood is surgically drained immediately. People who have a bleeding disorder or who are taking anticoagulants are given injections of vitamin K and transfusions of plasma to eliminate or reduce the tendency to bleed.

If the cause is cancer, treatment usually includes surgery, radiation therapy, or both.

Cervical Spondylosis

Cervical spondylosis is degeneration of the disks and vertebrae in the neck, putting pressure on (compressing) the spinal cord in the neck.

Osteoarthritis is the usual cause.

Osteoarthritis is the usual cause.

The first symptoms are often an unsteady, jerky walk and pain and loss of flexibility in the neck.

The first symptoms are often an unsteady, jerky walk and pain and loss of flexibility in the neck.

Magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography can confirm the diagnosis.

Magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography can confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment includes a soft neck collar, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, muscle relaxants, and sometimes surgery.

Treatment includes a soft neck collar, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, muscle relaxants, and sometimes surgery.

Cervical spondylosis usually affects middle-aged and older people. It is the most common cause of spinal cord dysfunction among people older than 55.

As people age, osteoarthritis becomes more common. It causes vertebrae in the neck to degenerate.

When bone in the vertebrae attempts to repair itself, it overgrows, producing abnormal outgrowths of bone (spurs) and narrowing the spinal canal in the neck. (The spinal canal is the passageway that runs through the center of the spine and contains the spinal cord.) The disks between vertebrae also degenerate, decreasing the cushioning that otherwise protects the spinal cord. As a result, the spinal cord may be compressed, causing dysfunction. Some people are born with a narrow spinal canal. In them, compression due to spondylosis may be more severe.

Often, the spinal nerve roots (the part of spinal nerves located next to the cord (see art on page 626) are also compressed.

Occasionally in people with osteoarthritis, flexing the neck causes one vertebra to slip over the vertebra next to it (a disorder called spondylolisthesis). As a result, the spinal canal is suddenly narrowed, and each time the neck moves, the spinal cord is slightly but repeatedly injured.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Cervical spondylosis is the most common cause of spinal cord problems in people over 55.

Symptoms

Symptoms may result from compression of the spinal cord, the spinal nerve roots, or both.

If the spinal cord is compressed, a change in walking is usually the first sign. Leg movements may become jerky (spastic), and walking becomes unsteady. Sensation may be decreased in the feet and hands. The neck may be painful and become less flexible. Reflexes may be increased, sometimes causing muscle spasms, particularly in the legs. Coughing, sneezing, and other movements of the neck may worsen symptoms. Sometimes the hands are affected more than the legs and feet. If severe, compression may impair bladder and bowel function.

If spinal nerve roots are compressed, the neck is usually painful, and the pain often radiates to the head, shoulders, or arms. Muscles in one or both arms may become weak and waste away, making the arms limp. Reflexes in the arms may be decreased.

Diagnosis

Doctors suspect cervical spondylosis based on symptoms, especially in older people or in people who have osteoarthritis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) can confirm the diagnosis. MRI provides much more information because it shows the spinal cord and roots. CT does not. However, both procedures show where the spinal canal is narrowed, how compressed the spinal cord is, and which spinal nerve roots may be affected.

Treatment

Without treatment, symptoms of spinal cord dysfunction due to cervical spondylosis sometimes lessen or stabilize, but they may worsen.

Initially, especially if only nerve roots are compressed, a soft neck collar, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, and muscle relaxants such as methocarbamol may provide relief.

If the spinal cord is compressed, surgery is usually needed. An incision may be made through the front of the neck (anterior cervical fusion) or back of the neck (posterior laminectomy). Part of the affected vertebrae is removed to make more room for the spinal cord. Bone spurs, if present, are removed, and the spine may be stabilized by fusing the vertebrae together. As a rule, surgery does not reverse the existing nerve damage, but it prevents additional nerve damage. The earlier the surgery, the better is the outcome.

Because the spine may be unstable after surgery, people may need to wear a rigid brace to hold the head still while healing occurs.

If muscle spasms occur, baclofen, a muscle relaxant, helps relieve them.

Syrinx

A syrinx is a fluid-filled cavity that develops in the spinal cord (called a syringomyelia), in the brain stem (called a syringobulbia), or in both.

Syrinxes may be present at birth or develop later because of an injury or a tumor.

Syrinxes may be present at birth or develop later because of an injury or a tumor.

People become less sensitive to pain and temperature and experience weakness in the hands and legs, or they may have vertigo and problems with eye movements, taste, and speech.

People become less sensitive to pain and temperature and experience weakness in the hands and legs, or they may have vertigo and problems with eye movements, taste, and speech.

Magnetic resonance imaging with a contrast agent can detect a syrinx.

Magnetic resonance imaging with a contrast agent can detect a syrinx.

Surgery to drain the syrinx may be done, but it may not correct the problem.

Surgery to drain the syrinx may be done, but it may not correct the problem.

Syrinxes are rare. In about half of the people who have a syrinx, it is present at birth, and then for poorly understood reasons, it enlarges during the teen or young adult years. Often, children who have a syrinx at birth also have other structural abnormalities of the brain, spinal cord, or junction between the skull and spine. Usually, syrinxes that develop later in life are due to injuries or tumors. About 30% of tumors that originate in the spinal cord eventually produce a syrinx.

Syrinxes that grow in the spinal cord press on it from within. They tend to first affect nerve fibers that carry information about pain and temperature from the body to the brain. Later, they affect fibers that carry signals from the brain to stimulate muscle movement. Syrinxes can occur anywhere along the length of the spinal cord. But they often begin in the neck and may extend downward to affect the entire cord. Syrinxes that extend into or begin in the lower part of the brain stem may compress pathways of the spinal cord and cranial nerves (which lead directly from the brain to other parts of the head and neck).

Symptoms

Symptoms usually begin subtly between adolescence and about age 45.

Syrinxes in the neck often make people less sensitive to pain and temperature, particularly in the arms, upper back, lower neck, and hands. Thus, cuts and burns on the arms and hands are common. People may not recognize this decreased sensitivity for years. As a syrinx expands and lengthens, it can cause weakness and atrophy, usually beginning in the hands and later causing weakness and spasms in the legs. Symptoms may be more severe on one side of the body.

Syrinxes in the brain stem can cause vertigo, nystagmus (rapid movement of the eyes in one direction followed by a slower drift back to the original position), loss of sensation in the face (on one or both sides), loss of taste, difficulty speaking, hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, and weakness and wasting away (atrophy) of the tongue.

Diagnosis

Doctors may suspect a syrinx in a young child or teenager who has typical symptoms. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with a paramagnetic contrast agent, such as gadolinium, can outline the syrinx (and a tumor if present).

Treatment

A neurosurgeon may make a hole in a syrinx to drain it and prevent it from expanding, but surgery does not always correct the problem. Even if the syrinx is drained, the nervous system may already be damaged irreversibly. Symptoms may not be relieved, or the syrinx may recur.

Disorders that contributed to or caused the syrinx (such as structural abnormalities or spinal tumors) are corrected when possible.

Hereditary Spastic Paraparesis

Hereditary spastic paraparesis is a rare hereditary disorder that causes gradual weakness with muscle spasms (spastic weakness) in the legs.

People have exaggerated reflexes, cramps, and spasms, making walking difficult.

People have exaggerated reflexes, cramps, and spasms, making walking difficult.

Doctors look for other family members who have the disorder, rule out disorders that can cause similar symptoms, and may do genetic tests.

Doctors look for other family members who have the disorder, rule out disorders that can cause similar symptoms, and may do genetic tests.

Treatment includes physical therapy, exercise, and drugs to reduce spasticity.

Treatment includes physical therapy, exercise, and drugs to reduce spasticity.

Hereditary (familial) spastic paraparesis affects both sexes and may begin at any age. It affects about 3 of 100,000 people. Usually, the gene for this disorder is dominant (see page 12). Therefore, children of a person with the disorder have a 50% chance of developing it. This disorder has several forms. All forms cause degeneration of the nerve pathways that carry signals from the brain down the spinal cord (to muscles). More than one area of the spinal cord may be affected.

Symptoms

Symptoms may begin at any age—from age 1 to old age—depending on the form.

Reflexes become exaggerated, and leg cramps, twitches, and spasms occur, making leg movements stiff and jerky (called a spastic gait). Walking gradually becomes more difficult. People may stumble or trip because they tend to walk on their tiptoes with the feet turned inwards. Shoes are often worn down in the area over the big toe. Fatigue is common. In some people, muscles in the arms also become weak and stiff.

Usually, symptoms continue to slowly worsen, but sometimes they level off after adolescence. Life span is not affected.

About 10% of people with the disorder have other abnormalities due to damage of the brain, spinal cord, or nerves. For example, they may have eye problems, lack of muscle control, hearing loss, mental retardation, dementia, and peripheral nerve disorders.

Diagnosis

The disorder is diagnosed by excluding other disorders that cause similar symptoms (such as multiple sclerosis and spinal cord compression) and by determining whether other family members have hereditary spastic paraparesis. Blood tests (genetic testing) are sometimes done to check for the genes that cause the disorder.

Treatment

Treatment focuses on relieving symptoms. Physical therapy and exercise can help maintain mobility and muscle strength, improve range of motion and endurance, reduce fatigue, and prevent cramps and spasms.

Baclofen is the drug of choice to reduce spasticity. Alternatively, botulinum toxin, clonazepam, dantrolene, diazepam, or tizanidine may be used. Some people benefit from using splints, a cane, or crutches. A few people require a wheelchair.

Acute Transverse Myelitis

Acute transverse myelitis is inflammation that affects the spinal cord across its entire width (transversely) and thus blocks transmission of nerve impulses traveling up or down the spinal cord.

The disorder may develop in people who have certain disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, Lyme disease, or lupus, or who take certain drugs.

The disorder may develop in people who have certain disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, Lyme disease, or lupus, or who take certain drugs.

People have sudden back pain and feel a band of tightness around the affected area, sometimes followed by severe symptoms, such as paralysis.

People have sudden back pain and feel a band of tightness around the affected area, sometimes followed by severe symptoms, such as paralysis.

Magnetic resonance imaging may help doctors make the diagnosis, but a spinal tap may be needed.

Magnetic resonance imaging may help doctors make the diagnosis, but a spinal tap may be needed.

About one third of people recover, about one third continue to have some problems, and about one third recover very little.

About one third of people recover, about one third continue to have some problems, and about one third recover very little.

The cause is treated if possible, or treatment may involve corticosteroids or sometimes plasma exchange.

The cause is treated if possible, or treatment may involve corticosteroids or sometimes plasma exchange.

In the United States, acute transverse myelitis is estimated to occur in about 1,400 people each year. Also, about 33,000 people are thought to have some type of disability due to the disorder. The entire width of one or more areas of the spinal cord, usually in the chest (thoracic area), becomes inflamed.

What triggers acute transverse myelitis is unknown, but it may result from an autoimmune reaction (when the immune system misinterprets the body’s tissues as foreign and attacks them). The disorder may develop during the following:

Multiple sclerosis (most commonly)

Multiple sclerosis (most commonly)

Neuromyelitis optica, a disorder that can also cause visual problems and may come and go

Neuromyelitis optica, a disorder that can also cause visual problems and may come and go

Certain bacterial infections (such as Lyme disease, syphilis, or tuberculosis)

Certain bacterial infections (such as Lyme disease, syphilis, or tuberculosis)

Inflammation of blood vessels (vasculitis), including systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus)

Inflammation of blood vessels (vasculitis), including systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus)

Viral meningoencephalitis (an infection of the brain and its surrounding tissues)

Viral meningoencephalitis (an infection of the brain and its surrounding tissues)

Use of certain antiparasitic or antifungal drugs

Use of certain antiparasitic or antifungal drugs

Intravenous injection of heroin or amphetamines

Intravenous injection of heroin or amphetamines

It sometimes develops after mild viral infections or a vaccination.

Symptoms

Usually, symptoms begin suddenly with pain in the back and a bandlike tightness around the affected area of the body (such as the chest or abdomen). Within hours to a few days, tingling, numbness, and muscle weakness develop in the feet and move upward. Urinating becomes difficult, although some people feel an urgent need to urinate (urgency). Symptoms may worsen over several more days and may become severe, resulting in paralysis, loss of sensation, retention of urine, and loss of bladder and bowel control. The degree of disability depends on the location (level) of the inflammation in the spinal cord and the severity of the inflammation.

Diagnosis

Symptoms suggest the diagnosis. But doctors must distinguish acute transverse myelitis from other disorders that cause similar symptoms, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, spinal cord compression, or blockage of the blood supply to the spinal cord. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is done first. If MRI does not detect spinal cord compression, a spinal tap (lumbar puncture) is done to obtain a sample of spinal cord fluid (see page 635). If acute transverse myelitis is present, the number of certain white blood cells and the protein level in the fluid is increased. If the disorder is advanced, MRI typically shows swelling of the spinal cord due to inflammation.

Tests, such as a chest x-ray and blood tests, are also done to look for the cause. Doctors may also ask people about use of drugs.

Prognosis

Occasionally, the disorder recurs in people with multiple sclerosis or lupus. Multiple sclerosis eventually develops in about 10 to 20% of people who have transverse myelitis with no identified cause.

Generally, the more quickly the disorder progresses, the worse the outlook. Severe pain suggests worse inflammation. The outcome is split evenly:

About one third of people recover.

About one third of people recover.

About one third continue to have some muscle weakness and urinary problems (urgency or loss of bladder control).

About one third continue to have some muscle weakness and urinary problems (urgency or loss of bladder control).

About one third recover very little, remaining confined to a wheelchair or bed, continuing to have bladder and bowel problems, and requiring help with daily activities.

About one third recover very little, remaining confined to a wheelchair or bed, continuing to have bladder and bowel problems, and requiring help with daily activities.

Treatment

If transverse myelitis is caused by another disorder, that disorder is treated.

If the cause cannot be identified, high doses of corticosteroids such as prednisone are often given to suppress the immune system, which may be involved in acute transverse myelitis. Plasma exchange—removal of a large amount of plasma (the liquid part of blood) plus plasma transfusions—may also be done. However, whether these treatments are useful is unclear.

Symptoms are treated.

Blockage of the Spinal Cord’s Blood Supply

Blockage of an artery carrying blood to the spinal cord prevents the cord from getting blood and thus oxygen. As a result, tissues can die (called infarction).

Causes include severe atherosclerosis, inflammation of blood vessels, and blood clots.

Causes include severe atherosclerosis, inflammation of blood vessels, and blood clots.

Sudden back pain with pain radiating from the affected area is followed by muscle weakness and inability to feel heat, cold, or pain in the affected areas and sometimes paralysis.

Sudden back pain with pain radiating from the affected area is followed by muscle weakness and inability to feel heat, cold, or pain in the affected areas and sometimes paralysis.

Magnetic resonance imaging or myelography is usually done.

Magnetic resonance imaging or myelography is usually done.

Treatment focuses on correcting the cause if possible or on relieving symptoms.

Treatment focuses on correcting the cause if possible or on relieving symptoms.

Spinal cord dysfunction and paralysis are usually permanent.

Spinal cord dysfunction and paralysis are usually permanent.

Like all tissues in the body, the spinal cord requires a constant supply of oxygenated blood. Only a few arteries, which are branches of the aorta, supply blood to the front part of the spinal cord. But this blood accounts for three fourths of the blood the spinal cord receives. Thus, blockage of any one of these arteries can be disastrous. Such a blockage occasionally results from the following:

Severe atherosclerosis of the aorta

Severe atherosclerosis of the aorta

Separation of the layers of the aorta’s wall (aortic dissection)

Separation of the layers of the aorta’s wall (aortic dissection)

Inflammation of blood vessels (vasculitis), such as polyarteritis nodosa

Inflammation of blood vessels (vasculitis), such as polyarteritis nodosa

A blood clot that breaks off from the wall of the heart and travels through the bloodstream (becoming an embolus)

A blood clot that breaks off from the wall of the heart and travels through the bloodstream (becoming an embolus)

Surgery to repair a bulge (aneurysm) in the abdominal aorta

Surgery to repair a bulge (aneurysm) in the abdominal aorta

Symptoms

The first symptoms are usually sudden back pain and pain that radiates along the nerves branching from the affected area of the spinal cord. The pain is followed by muscle weakness, and people cannot feel heat, cold, or pain in areas controlled by the part of the spinal cord below the level of the blockage. People immediately notice symptoms, which may lessen slightly over time. If the blood supply to the front of the spinal cord is greatly reduced, the legs are numb and paralyzed. But sensations transmitted through the back of the cord—including touch, the ability to feel vibration, and the ability to sense where the limbs are without looking at them (position sense)—remain intact. The back of the cord receives blood from other sources.

Weakness and paralysis can lead to the development of pressure sores and breathing difficulties. Bladder and bowel function may be impaired, as may sexual function.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually based on symptoms. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or, if MRI is unavailable, myelography (see page 636) is done. These tests can help doctors rule out other disorders that cause similar symptoms. A spinal tap (lumbar puncture—see page 635) may be done to rule out transverse myelitis as the cause of symptoms. An-giography can confirm that an artery to the front of the spinal cord is blocked, but it is usually unnecessary.

Treatment

When possible, the cause (such as aortic dissection or polyarteritis nodosa) is treated, but otherwise, treatment focuses on relieving symptoms because paralysis and spinal cord dysfunction are usually permanent.

Because some sensations are lost and paralysis may develop, preventing pressure sores from forming is important. Therapy to help fluids drain from the lungs (such as deep breathing exercises, postural drainage, and suctioning) may be necessary. Physical and occupational therapy (see page 53) can help preserve muscle function. Because bladder function is usually impaired, a catheter is needed to drain urine. This treatment prevents the bladder from enlarging and forming bulges that weaken it.

Subacute Combined Degeneration

Subacute combined degeneration is progressive degeneration of the spinal cord due to vitamin B12 deficiency.

Nerve fibers that control movement and sensation are damaged.

Nerve fibers that control movement and sensation are damaged.

People have general weakness, tingling and numbness in the hands and feet, and stiff limbs and may become irritable, drowsy, and confused.

People have general weakness, tingling and numbness in the hands and feet, and stiff limbs and may become irritable, drowsy, and confused.

Blood tests can confirm vitamin B12 deficiency.

Blood tests can confirm vitamin B12 deficiency.

Vitamin B12, if promptly given by injection or by mouth, usually results in complete recovery.

Vitamin B12, if promptly given by injection or by mouth, usually results in complete recovery.

This disorder affects about 1 of 10,000 people, usually those older than 40. It is due to a deficiency of vitamin B12, which usually also causes pernicious anemia. Usually, the deficiency is not related to diet but to the body’s inability to absorb vitamin B12.

Vitamin B12 is necessary for the formation and maintenance of a fatty sheath (myelin sheath) that surrounds some nerve cells and that speeds transmission of nerve signals. In subacute combined degeneration, the sheath is damaged, causing sensory and motor nerve fibers from the spinal cord to degenerate. The brain, nerves of the eyes, and peripheral nerves are sometimes also damaged.

Symptoms

The disorder begins with a general feeling of weakness. Tingling, a pins-and-needles sensation, and numbness are felt in both hands and feet. These sensations tend to be constant and to gradually worsen. People may not be able to feel vibrations and may lose the sense of where their limbs are (position sense). The limbs feel stiff, movements become clumsy, and walking may become difficult. Reflexes may be decreased, increased, or absent. Vision may be reduced.

People who have this disorder may become irritable, apathetic, drowsy, suspicious, and confused. Their emotions may change rapidly and unpredictably. Rarely, dementia develops.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Blood tests to measure levels of vitamin B12 can confirm the deficiency.

Recovery is more likely if the disorder is treated early. When treated within a few weeks after symptoms appear, most people recover completely. If treatment is delayed, the progression of symptoms may be slowed or stopped, but full recovery of lost function is less likely.

Most people are immediately given injections of vitamin B12, which are continued indefinitely to prevent symptoms from recurring. Large doses of vitamin B12 taken by mouth can be used if the deficiency is mild and symptoms of nerve damage have not developed.

Tropical Spastic Paraparesis/HTLV-1-Associated Myelopathy

Tropical spastic paraparesis/HTLV-1-associated myelopathy is a slowly progressive disorder of the spinal cord caused by the human T-lymphotrophic virus 1 (HTLV-1).

The virus is spread through sexual contact, use of illicit intravenous drugs, exposure to blood, or breastfeeding.

The virus is spread through sexual contact, use of illicit intravenous drugs, exposure to blood, or breastfeeding.

People have weakness, stiffness, and muscle spasms in the legs, making walking difficult, and many have urinary incontinence.

People have weakness, stiffness, and muscle spasms in the legs, making walking difficult, and many have urinary incontinence.

To diagnose the disorder, doctors ask about possible exposure to the virus and do magnetic resonance imaging and a spinal tap.

To diagnose the disorder, doctors ask about possible exposure to the virus and do magnetic resonance imaging and a spinal tap.

Drugs, such as corticosteroids, may help, and spasms are treated with muscle relaxants.

Drugs, such as corticosteroids, may help, and spasms are treated with muscle relaxants.

The human T-lymphotrophic virus 1 (HTLV-1) virus is similar to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes AIDS. The HTLV-1 virus can cause certain kinds of leukemia and lymphoma (cancers of the white blood cells). This virus is transmitted through sexual contact, use of illicit intravenous drugs, or exposure to blood. It can be transmitted from mother to child through breastfeeding. It is most common among prostitutes, IV drug users, people undergoing hemodialysis, and people from certain areas such as those near the equator, southern Japan, and parts of South America. A similar disorder can result from infection with a similar virus, human T-lymphotrophic virus 2 (HTLV-2).

The virus resides in white blood cells. Because the spinal fluid contains white blood cells, the spinal cord can be damaged. Damage to the spinal cord results more from the body’s reaction to the virus than from the virus itself.

Symptoms

The muscles in both legs gradually become weak. People may not be able to feel vibrations and may lose the sense of where their feet and toes are (position sense). Their limbs feel stiff, movements become clumsy, and walking may become difficult. Muscle spasms in the legs are common, as is urinary incontinence. The disorder usually progresses over several years.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually based on symptoms and the person’s risk of being exposed to the virus. Thus, a doctor may ask people about their sexual contacts and use of illicit intravenous drugs. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spinal cord is done. Samples of blood and spinal fluid, obtained by a spinal tap (lumbar puncture), are tested for parts of the virus or antibodies to the virus.

Treatment

Interferon-alpha, immune globulin (given intravenously), and corticosteroids (such as methylprednisolone, given by mouth) may help, although their usefulness has not been established. Spasms can be treated with muscle relaxants such as baclofen or tizanidine.