CHAPTER 155

Blood Transfusion

A blood transfusion is the transfer of blood or a blood component from one person (a donor) to another (a recipient).

In the United States, about 29 million blood transfusions are given every year. Transfusions are given to increase the blood’s ability to carry oxygen, restore the body’s blood volume, improve immunity, and correct clotting problems. Accident victims, people undergoing surgery, and people receiving treatment for cancers (such as leukemia) or other diseases (such as the blood diseases sickle cell anemia and thalassemia) are typical recipients.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) strictly regulates the collection, storage, and transportation of blood and its components. These regulations were developed to protect both the donor and the recipient. Additional standards are upheld by many state and local health authorities, as well as by organizations such as the American Red Cross and the American Association of Blood Banks. Because of these regulations, giving and receiving blood is very safe. However, transfusions still pose risks for the recipient, such as allergic reactions, fever and chills, excess blood volume, and bacterial and viral infections. Even though the chance of contracting AIDS, hepatitis, or other infections from transfusions is remote, doctors are well aware of these risks and order transfusions only when there is no alternative.

Donation Process

Donating blood is very safe. The entire process of donating whole blood (that is, blood with all component cells) takes about 1 hour. Blood donors must be at least 17 years old and weigh at least 110 pounds. In addition, they must be in good health: their pulse, blood pressure, and temperature are measured, and a blood sample is tested to check for anemia. They are asked a series of questions about their health, factors that might affect their health, and countries they have visited.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

There are very few disorders that disqualify people from giving blood.

Most people who are deferred from giving blood are eligible to donate at a later time.

Doctors test donated blood for many infectious diseases, so the chance a person will get a disease from donated blood is rare.

Conditions that permanently disqualify a person from donating blood include hepatitis B or C, heart disease, certain types of cancer (leukemia, lymphoma, and any type of cancer that has recurred after treatment or that has ever been treated with chemotherapy drugs), severe asthma, bleeding disorders, possible exposure to prion diseases (such as variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease—see page 766), AIDS, and possible exposure to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV, the virus that causes AIDS) due to high-risk behaviors (see page 1254). Conditions that temporarily disqualify a person include malaria (if it has been less than 3 years since the person last experienced symptoms), cancer that has been treated with surgery or radiation (if it has been less than 5 years since the person last received treatment), pregnancy, recent major surgery, poorly controlled high blood pressure, low blood pressure, anemia, the use of certain drugs, exposure to some forms of hepatitis, and a recent blood transfusion.

Blood Typing

Blood is classified by type. A person’s blood type is determined by the presence or absence of certain proteins (Rh factor and blood group antigens A and B) on the surface of red blood cells.

The four main blood types are A, B, AB, and O, and for each type, the blood is either Rh-positive or Rh-negative. For example, a person with O-negative blood has red blood cells that lack both A and B antigens and the Rh factor. A person with AB-positive blood has red blood cells that have A and B antigens and the Rh factor. Some blood types are far more common than others. The most common blood types in the United States are O-positive and A-positive, followed by B-positive, O-negative, A-negative, AB-positive, B-negative, and AB-negative.

A blood transfusion is safest when the blood type of the transfused blood precisely matches the recipient’s blood type. Therefore, before a transfusion, blood banks do a test called a “type and crossmatch” on the donor’s and the recipient’s blood. This test minimizes the chance of a dangerous or possibly fatal reaction.

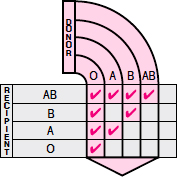

However, in an emergency, anyone can receive type O red blood cells. Thus, people with type O blood are known as universal donors. People with type AB blood can receive red blood cells from any blood type and are thus known as universal recipients. Recipients whose blood is Rh-negative must receive blood from Rh-negative donors, but recipients whose blood is Rh-positive may receive Rh-positive or Rh-negative blood.

Generally, donors are not allowed to give blood more than once every 56 days. The practice of paying donors for blood has almost disappeared,

Testing Donated Blood for Infections

Blood transfusions can transmit infectious organisms carried in the donor’s blood. That is why health officials have restricted blood donor eligibility and made blood testing thorough. All blood donations are tested for infection with the organisms that cause viral hepatitis, AIDS, selected other viral disorders (such as West Nile virus), Chagas’ disease, and syphilis.

VIRAL HEPATITIS

Donated blood is tested for infection with the viruses that cause the types of viral hepatitis (types B and C) that are transmitted by blood transfusions. These tests cannot identify all cases of infected blood, but with the rigorous testing and donor screening procedures, a transfusion poses almost no risk of transmitting hepatitis C. The current risk is 1 infection for every 1,500,000 units of blood transfused. Hepatitis B remains the most common potentially serious disorder transmitted by blood transfusions, with a current risk of about 1 infection for every 137,000 units of blood transfused.

AIDS

In the United States, donated blood is tested for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the cause of AIDS. The test is not 100% accurate, but potential donors are interviewed as part of the screening process. Interviewers ask about risk factors for AIDS—for instance, whether the potential donors or their sex partners have injected drugs or had sex with a man who has male sex partners. Because of the blood test and the screening interview, the risk of contracting HIV infection through a blood transfusion is extremely low—1 in 2,000,000 according to recent estimates.

SYPHILIS

Blood transfusions rarely transmit syphilis. Not only are blood donors screened and donations tested for the organism that causes syphilis, but the donated blood is also refrigerated at low temperatures, which kills the infectious organisms.

because it encouraged needy people to present themselves as donors and then sometimes to deny having any conditions that would disqualify them.

A person who is deemed eligible to donate blood sits in a reclining chair or lies on a cot. A health care worker examines the inside surface of the person’s elbow and determines which vein to use. After the area immediately surrounding the vein is cleaned, a needle is inserted into the vein and temporarily secured with a sterile covering. A stinging sensation is usually felt when the needle is first inserted, but otherwise the procedure is painless. Blood moves through the needle and into a collecting bag. The actual collection of blood takes only about 10 minutes.

The standard unit of donated blood is about 1 pint (about 450 milliliters). Freshly collected blood is sealed in plastic bags containing preservatives and an anticlotting compound. A small sample from each donation is tested for the infectious organisms that cause AIDS, viral hepatitis, selected other viral disorders, and syphilis.

Types of Transfusions

Most blood donations are divided (fractionated) into their components: red blood cells, platelets, clotting factors, plasma, antibodies (immunoglobulins), and white blood cells. Depending on the situation, people may receive only the cells from blood, only the clotting factors from blood, or some other blood component. Transfusing only selected blood components allows the treatment to be specific, reduces the risks of side effects, and can efficiently use the different components from a single unit of blood to treat several people.

Red Blood Cells: Packed red blood cells, the most commonly transfused blood component, can restore the blood’s oxygen-carrying capacity. This component may be given to a person who is bleeding or who has severe anemia. The red blood cells are separated from the fluid component of the blood (plasma) and from the other cellular and cell-like components. This step concentrates the red blood cells so that they occupy less space, thus the term “packed.” Red blood cells can be refrigerated for up to 42 days. In special circumstances—for instance, to preserve a rare type of blood—red blood cells can be frozen for up to 10 years.

Platelets: Platelets can help restore the blood’s clotting ability. They are usually given to people with too few platelets (thrombocytopenia), which may result in severe and spontaneous bleeding. Platelets can be stored for only 5 to 7 days.

Blood Clotting Factors: Blood clotting factors are proteins found in blood plasma that normally work with platelets to help the blood clot. Clotting factors may be obtained from plasma or manufactured. Manufactured proteins are called recombinant factor concentrates. Without clotting factors, bleeding would not stop after an injury. Individual concentrated blood clotting factors can be given to people who have an inherited bleeding disorder, such as hemophilia or von Willebrand’s disease, and to those who are unable to produce enough clotting factors (usually because of severe infection or liver disease).

Plasma: Plasma, the fluid component of the blood, contains many proteins, including blood clotting factors. Plasma is used for bleeding disorders in which the missing clotting factor is unknown or when the specific clotting factor is not available. Plasma also is used when bleeding is caused by insufficient production of all or many of the different clotting factors, as a result of liver failure or severe infection. Plasma that is frozen right after it is separated from the cells of donor blood (fresh frozen plasma) can be stored for up to 1 year.

Antibodies: Antibodies (immunoglobulins), the disease-fighting components of blood, are sometimes given to provide temporary immunity to people who have been exposed to an infectious disease or who have low antibody levels. Infections for which antibodies are available include chicken-pox, hepatitis, rabies, and tetanus. Antibodies are produced from treated plasma donations.

White Blood Cells: White blood cells are transfused to treat life-threatening infections in people who have a greatly reduced number of white blood cells or whose white blood cells are functioning abnormally. The use of white blood cell transfusions is rare, because improved antibiotics and the use of cytokine growth factors have greatly reduced the need for such transfusions. White blood cells are obtained by hemapheresis and can be stored for up to 24 hours.

Blood Substitutes: Blood substitutes that use certain chemicals or specially treated solutions of hemoglobin (a protein that allows red blood cells to carry oxygen) to carry and deliver oxygen to tissues are being developed. These solutions can be stored at room temperature for up to 2 years, making them attractive for transport to the site of trauma or to the battlefield. However, further research is needed before these blood substitutes become available for routine use.

Special Donation Procedures

Plateletpheresis: In plateletpheresis, a donor gives only platelets rather than whole blood. Whole blood is drawn from the donor, and a machine that separates the blood into its components selectively removes the platelets and returns the rest of the blood to the donor. Because donors get most of their blood back, they can safely give 8 to 10 times as many platelets during one of these procedures as they would give in a single donation of whole blood. Collecting platelets from a donor takes about 1 to 2 hours, compared with collecting whole blood, which takes about 10 minutes.

Autologous Transfusion: In an autologous transfusion, donors are recipients of their own blood. For example, in the weeks before undergoing elective surgery, a person may donate several units of blood to be transfused if needed during or after the surgical procedure. The person takes iron pills after donating the blood to help the body replenish the lost blood cells before surgery. Also, during some types of surgery and in certain kinds of injuries, blood that is lost can be collected and immediately given back to the person (intraoperative blood salvage). An autologous transfusion is the safest type of blood transfusion, because it eliminates the risks of incompatibility and blood-borne disease.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Doctors can specify what type of blood cells are given during a transfusion so that people get only those cells that are needed to treat their disorder.

Directed or Designated Donation: Family members or friends can donate blood specifically for one another if the recipient’s and donor’s blood types and Rh factors are compatible. For some recipients, knowing who donated the blood is comforting, although a donation from a family member or friend is not necessarily safer than one from an unrelated person. Blood from a family member is tested as are all blood samples and then treated with radiation to prevent graft-versus-host disease, which, although rare, occurs more often when the recipient and donor are related.

Stem Cell Pheresis: In stem cell pheresis, a donor gives only stem cells (undifferentiated cells that can develop into any type of cell) rather than whole blood. Prior to the donation procedure, the donor receives an injection of a special type of protein (growth factor) that stimulates the bone marrow to release stem cells into the bloodstream. Whole blood is drawn from the donor, and a machine that separates the blood into its components selectively removes the stem cells and returns the rest of the blood to the donor. Stem cell donors must be compatible with recipients by lymphocyte type (human leukocyte antigen, or HLA), a type of protein found on certain cells, rather than blood type. Stem cells are sometimes used to treat people with leukemia, lymphoma, or other cancers of the blood. This procedure is called stem cell transplantation. The recipient’s own stem cells can be obtained, or donated stem cells can be given.

Controlling Diseases by Purifying the Blood

In hemapheresis, blood is removed from a person and then returned after fluid, substances in the fluid, blood cells, or platelets are removed or reduced in quantity. Sometimes this process is used to obtain needed blood cells or platelets from a donor (for example, stem cell pheresis or plateletpheresis). This process is also used to purify blood by removing harmful substances or excessive numbers of blood cells or platelets in people with serious illnesses who have not responded to other treatments. To be helpful for purifying blood, hemapheresis must remove the undesirable substance or blood cell faster than the body produces it.

The two most common types of hemapheresis that are used to purify blood are plasmapheresis and cytapheresis.

In plasmapheresis, harmful substances are removed from the plasma. Plasmapheresis is used to treat such disorders as myasthenia gravis and Guillain-Barré syndrome (neurologic disorders that cause muscle weakness), Goodpasture’s syndrome (an autoimmune disorder involving bleeding in the lungs and kidney failure), pemphigus vulgaris (severe, sometimes fatal, blistering of the skin), cryoglobulinemia (a type of abnormal antibody formation), and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (a rare clotting disorder).

In cytapheresis, excess numbers of certain blood cells are removed. Cytapheresis can be used to treat polycythemia (an excess of red blood cells), certain types of leukemia (a type of cancer in which there are excess white blood cells), and thrombocythemia (an excess of platelets).

Hemapheresis is repeated only as often as necessary because the large fluid shifts between blood vessels and tissues that occur as blood is removed and returned may cause complications in people who are already ill. Hemapheresis can help control some diseases but generally does not cure them.

Precautions and Adverse Reactions

To minimize the chance of an adverse reaction during a transfusion, health care practitioners take several precautions. Before starting the transfusion, usually a few hours or even a few days beforehand, a technician mixes a drop of the donor’s blood with the recipient’s to make sure they are compatible. This procedure is called cross-matching.

After double-checking labels on the bags of blood that are about to be given to ensure the units are intended for that recipient, the health care practitioner gives the blood to the recipient slowly, generally over 1 to 2 hours for each unit of blood. Because most adverse reactions occur during the first 15 minutes of the transfusion, the recipient is closely observed at first. After that, a nurse checks on the recipient periodically and must stop the transfusion if an adverse reaction occurs.

Most transfusions are safe and successful; however, mild reactions occur occasionally, and severe and even fatal reactions, rarely. The most common reactions are fever and allergic reactions (hypersensitivity), which occur in about 1 to 2% of transfusions. Symptoms of an allergic reaction include itching, a widespread rash, swelling, dizziness, and headache. Less common symptoms are breathing difficulties, wheezing, and muscle spasms. Rarely, an allergic reaction is severe enough to cause low blood pressure and shock. Another rare reaction, called transfusion-related acute lung injury, or TRALI, is caused by antibodies in the donor’s plasma. This reaction, which is more common when the donor is a woman who has been pregnant, may cause serious breathing difficulties. More general use of male donor plasma has decreased the number of people who have this reaction.

Treatments are available that allow transfusions to be given to people who previously had allergic reactions to them. People who have allergic reactions to donated blood may have to be given washed red blood cells. Washing the red blood cells removes components of the donor blood that may cause allergic reactions. More commonly, the transfused blood is filtered to reduce the number of white blood cells (a process called leukocyte reduction). Leukocyte reduction is usually done by placing a special filter in the tubing through which the transfusion is flowing. Alternatively, the blood may be filtered before it is stored.

Despite careful typing and cross-matching of blood, mismatches due to subtle differences between donor and recipient blood (and, very rarely, errors) can still occur that cause the transfused red blood cells to be destroyed shortly after the transfusion (a hemolytic reaction). Usually, this reaction starts as general discomfort or anxiety during or immediately after the transfusion. Sometimes breathing difficulty, chest pressure, flushing, and severe back pain develop. Very rarely, the reactions become more severe and even fatal. A doctor can confirm that a hemolytic reaction is destroying red blood cells by checking to see whether hemoglobin released from these cells is in the person’s blood and urine.

Transfusion recipients can become overloaded with fluid. Recipients who have heart disease are most vulnerable, so their transfusions are given more slowly and they are monitored closely.

Graft-versus-host disease is an unusual complication that affects primarily people whose immune system is impaired by drugs or disease. In this disease, the recipient’s (host’s) tissues are attacked by the donated white blood cells (the graft). The symptoms include fever, rash, low blood pressure, low blood counts, tissue destruction, and shock. These reactions can be fatal but are eliminated by treating with radiation those blood products that are intended for people with a weakened immune system.