CHAPTER 174

Bacterial Infections

Bacteria are microscopic, single-celled organisms. There are thousands of different kinds, and they live in every conceivable environment all over the world. They live in soil, seawater, and deep within the earth’s crust. Some bacteria have been reported even to live in radioactive waste. Some bacteria live in the bodies of people and animals—on the skin and in the airways, mouth, and digestive, reproductive, and urinary tracts—often without causing any harm.

Only a few kinds of bacteria cause disease. They are called pathogens. Sometimes bacteria that normally reside harmlessly in the body cause disease. Bacteria can cause disease by producing harmful substances (toxins), invading tissues, or doing both.

Classification

Bacteria can be classified in several ways:

Scientific names: Bacteria, like other living things, are classified by genus (based on having one or several similar characteristics) and, within the genus, by species. Their scientific name is genus followed by species (for example, Clostridium botulinum). Within a species, there may be different types, called strains. Strains differ in genetic makeup and chemical components. Sometimes certain drugs and vaccines are effective only against certain strains.

Scientific names: Bacteria, like other living things, are classified by genus (based on having one or several similar characteristics) and, within the genus, by species. Their scientific name is genus followed by species (for example, Clostridium botulinum). Within a species, there may be different types, called strains. Strains differ in genetic makeup and chemical components. Sometimes certain drugs and vaccines are effective only against certain strains.

Staining: Bacteria may be classified by the color they turn after certain chemicals (stains) are applied to them. A commonly used stain is the Gram stain. Some bacteria stain blue. They are called gram-positive. Others stain pink. They are called gram-negative. Gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria stain differently because their cell walls are different. They also cause different types of infections, and different types of antibiotics are effective against them.

Staining: Bacteria may be classified by the color they turn after certain chemicals (stains) are applied to them. A commonly used stain is the Gram stain. Some bacteria stain blue. They are called gram-positive. Others stain pink. They are called gram-negative. Gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria stain differently because their cell walls are different. They also cause different types of infections, and different types of antibiotics are effective against them.

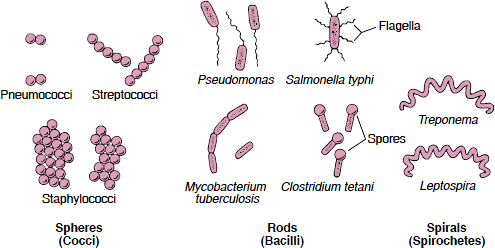

Shapes: All bacteria may be classified as one of three basic shapes: spheres (cocci), rods (bacilli), and spirals or helixes (spirochetes).

Shapes: All bacteria may be classified as one of three basic shapes: spheres (cocci), rods (bacilli), and spirals or helixes (spirochetes).

Need for oxygen: Bacteria are also classified by whether they need oxygen to live and grow. Those that need oxygen are called aerobes. Those that have trouble living or growing when oxygen is present are called anaerobes. Some bacteria, called facultative bacteria, can live and grow with or without oxygen.

Need for oxygen: Bacteria are also classified by whether they need oxygen to live and grow. Those that need oxygen are called aerobes. Those that have trouble living or growing when oxygen is present are called anaerobes. Some bacteria, called facultative bacteria, can live and grow with or without oxygen.

Bacterial Defenses

Bacteria have many ways of defending themselves.

Biofilm: Some bacteria secrete a substance that helps them attach to other bacteria, cells, or objects. This substance combines with the bacteria to form a sticky layer called biofilm. For example, certain bacteria form a biofilm on teeth (called dental plaque). The biofilm traps food particles, which the bacteria process and use, and in this process, they probably cause tooth decay. Biofilms also help protect bacteria from antibiotics.

Capsules: Some bacteria are enclosed in a protective capsule. This capsule helps prevent white blood cells, which fight infection, from ingesting the bacteria. Such bacteria are described as encapsulated.

Outer Membrane: Under the capsule, gram-negative bacteria have an outer membrane that protects them against certain antibiotics. When disrupted, this membrane releases toxic substances called endotoxins. Endotoxins contribute to the severity of symptoms during infections with gram-negative bacteria.

Spores: Some bacteria produce spores, which are an inactive (dormant) form. Spores can enable bacteria to survive when environmental conditions are difficult. When conditions are favorable, each spore germinates into an active bacterium.

Flagella: Flagella are long, thin filaments that protrude from the cell surface and enable bacteria to move. Bacteria without flagella cannot move on their own.

Antibiotic Resistance: Bacteria develop resistance to drugs because they acquire genes from other bacteria that have become resistant or because their genes mutate. For example, soon after the drug penicillin was introduced in the mid-1940s, a few individual Staphylococcus aureus bacteria acquired genes that made penicillin ineffective against them. The strains that possessed these special genes had a survival advantage when penicillin was commonly used to treat infections. Strains of Staphylococcus aureus that lacked these new genes were killed by penicillin, allowing the remaining penicillin-resistant bacteria to reproduce and over time become dominant. Chemists then altered the penicillin molecule, making a different but similar drug, methicillin, which could kill the penicillin-resistant bacteria. Soon after methicillin was introduced, strains of Staphylococcus aureus developed genes that made them resistant to methicillin and related drugs. These strains are called methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The genes that encode for drug resistance can be passed to following generations of bacteria or sometimes even to other species of bacteria.

How Bacteria Shape Up

The more often antibiotics are used, the more likely resistant bacteria are to develop. Therefore, doctors try to use antibiotics only when they are necessary. Giving antibiotics to people who probably do not have a bacterial infection, such as those who have cough and cold symptoms, does not make people better but does help create resistant bacteria. Because antibiotics have been so widely used (and misused), many bacteria are resistant to certain antibiotics.

Resistant bacteria can spread from person to person. Because international travel is so common, resistant bacteria can spread to many parts of the world in a short time. Spread of these bacteria in hospitals is a particular concern. Resistant bacteria are common in hospitals because antibiotics are so often necessary and hospital personnel and visitors may spread the bacteria if they do not strictly follow appropriate sanitary procedures. Also, many hospitalized patients have a weakened immune system, making them more susceptible to infection.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Botulinum toxin, produced by clostridial bacteria, can cause food poisoning and muscle paralysis but can also be used to reduce wrinkles and to treat muscle spasms.

Resistant bacteria can also spread to people from animals. Resistant bacteria are common among farm animals because antibiotics are often routinely given to healthy animals to prevent infections that can impair growth or cause illness.

Actinomycosis

Actinomycosis is a chronic infection caused mainly by Actinomyces israelii, anaerobic bacteria that normally reside on the enamel of teeth, gums, tonsils, and membranes lining the intestines and vagina.

Infection occurs only when tissue is broken, enabling the bacteria to enter deeper tissues.

Infection occurs only when tissue is broken, enabling the bacteria to enter deeper tissues.

Abscesses form in various areas, such as the intestine or face, causing pain, fever, and other symptoms.

Abscesses form in various areas, such as the intestine or face, causing pain, fever, and other symptoms.

Symptoms suggest the diagnosis, and doctors confirm it by taking x-rays and identifying the bacteria in a sample of infected tissue.

Symptoms suggest the diagnosis, and doctors confirm it by taking x-rays and identifying the bacteria in a sample of infected tissue.

Abscesses are drained, and antibiotics are given.

Abscesses are drained, and antibiotics are given.

With treatment, most people recover fully.

With treatment, most people recover fully.

These bacteria cause infection only when the surface of the tissue on which they reside is broken, enabling them to enter other, deeper tissues, which have no defenses against them. As the infection spreads, scar tissue and abnormal channels (called fistulas or tracts) form. After months to years, fistulas may eventually reach the skin and allow pus to drain. Pockets of pus (abscesses) may develop in the chest, abdomen, face, or neck.

Men are affected most often, but actinomycosis occasionally develops in women who use an intrauterine device (IUD).

Symptoms

Actinomycosis has several forms. All cause abscesses.

Abdominal: The bacteria infect the intestine, usually the area near the appendix, and the lining of the abdominal cavity (peritoneum). Chronic abdominal pain, fever, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, and severe weight loss are common symptoms. Fistulas may form from the interior of the abdomen to the skin above it and between the intestine and other organs.

Pelvic: The bacteria spread to the uterus, usually from an IUD that has been in place for years. Abscesses and scar tissue may form in the fallopian tubes, ovaries, and nearby organs such as the bladder and ureters. Fistulas may form between these organs. Symptoms include chronic abdominal or pelvic pain, fever, weight loss, and vaginal bleeding and discharge.

Cervicofacial: Usually, small, hard, sometimes painful swellings develop in the mouth and on the face, neck, or skin below the jaw (lumpy jaw). These swellings may soften and discharge pus that contains small, round, yellowish granules. The infection may extend to the cheek, tongue, throat, salivary glands, skull, bones of the neck (cervical vertebrae) and face, brain, or the space within the tissues covering the brain (meninges).

Thoracic: This form affects the chest (thorax). People have chronic chest pain and fever. They lose weight and cough, sometimes bringing up sputum. People probably become infected when they inhale fluids that contain bacteria from their mouth. Abscesses may form in the lungs and eventually spread to the membrane between the lungs and chest wall (pleura). There, abscesses cause irritation (pleuritis), and infected fluid collects (called an empyema). Fistulas may form, enabling the infection to spread to the ribs, skin of the chest, and spine.

Generalized: Rarely, the bacteria are carried in the bloodstream to infect other organs, such as the brain, lungs, liver, kidneys, and heart valves.

Diagnosis

Doctors suspect the infection in people who have typical symptoms. Then, x-rays are taken, and samples of pus or tissue are obtained and checked for Actinomyces israelii. Often, a needle is inserted through the skin to take a sample from an abscess or infected tissue. Sometimes computed tomography (CT) or ultrasonography is used to help doctors place the needle in the infected area. Sometimes surgery is necessary to remove a sample.

Characteristic x-ray findings and identification of the bacteria in a sample confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Treatment consists of draining abscesses with a needle (usually inserted through the skin) and giving high doses of antibiotics such as penicillin or tetracycline. Antibiotics may be needed for as long as 6 to 12 months.

Bacteria in the Body

The body normally contains several hundred different species of bacteria but many trillions of individual bacteria. The bacteria outnumber the cells of the body by about 10 to 1. Most of these bacteria reside on the skin and teeth, in the spaces between teeth and gums, and in the mucous membranes that line the throat, intestine, and vagina. The species differ at each site, reflecting the different environment at each site. Many of them are anaerobes—that is, they do not require oxygen.

Usually, these anaerobes do not cause disease. Many have useful functions, such as helping break down food in the intestine. However, these bacteria can cause disease if the mucous membranes are damaged. Then, bacteria can enter tissues that are usually off-limits to them and that have no defenses against them. The bacteria may infect nearby structures (such as the sinuses, middle ear, lungs, brain, abdomen, pelvis, and skin) or enter the bloodstream and spread.

What Are Clostridia?

Clostridia are bacteria that normally reside in the intestine of 3 to 8% of healthy adults and even more newborns. Clostridia also reside in animals, soil, and decaying vegetation. These bacteria do not require oxygen to live. That is, they are anaerobes.

Clostridia cause disease in different ways, depending on the species:

They may produce a toxin in food, which is then consumed, as occurs in foodborne botulism.

They may produce a toxin in food, which is then consumed, as occurs in foodborne botulism.

They may produce a toxin after they are in the body if circumstances enable them to multiply excessively (overgrow), as occurs in tetanus, Clostridium perfringens food poisoning, and a type of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis called Clostridium difficile-induced diarrhea and colitis.

They may produce a toxin after they are in the body if circumstances enable them to multiply excessively (overgrow), as occurs in tetanus, Clostridium perfringens food poisoning, and a type of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis called Clostridium difficile-induced diarrhea and colitis.

They may produce a toxin and invade tissue, causing infection, as occurs in gas gangrene.

They may produce a toxin and invade tissue, causing infection, as occurs in gas gangrene.

Clostridia can infect the gallbladder, colon, and female reproductive organs. Rarely, one species, Clostridium sordellii, causes toxic shock syndrome in women who have infections of the reproductive organs.

Clostridia may also spread to the blood (causing bacteremia). Widespread bacteremia (sepsis) can cause fever and serious symptoms such as low blood pressure, jaundice, and anemia. Sepsis can develop after a clostridial infection and be rapidly fatal.

Foodborne botulism can develop when people eat food that contains botulinum toxin, produced by Clostridium botulinum. Usually, botulism results from eating uncooked or undercooked food because heat (cooking) destroys the toxin. Botulinum toxin enters the bloodstream from the small intestine and is carried to nerves. This toxin prevents nerves from sending impulses to muscles. About 18 to 36 hours after consuming the toxin, people become tired and dizzy. Their mouth becomes dry. They may feel nauseated and vomit. The abdomen may swell (distend), and constipation may develop. Muscles of the face become slack or paralyzed, causing the eyelids and face to droop and vision to blur. Swallowing and talking become difficult. The muscle weakness then spreads to the upper torso and downward. The muscles involved in breathing may weaken—a problem that may become life threatening.

Clostridium perfringens food poisoning can develop when people eat food (usually beef) that contains bacteria (rather than the bacteria’s toxin). The bacteria develop from spores, which are inactive (dormant) forms of the bacteria that can survive the heat of cooking. If food that contains spores is not eaten soon after it is cooked, the spores develop into bacteria, which then multiply in the food. If the food is served without adequate reheating, the bacteria are consumed. They multiply in the small intestine and produce a toxin that causes watery diarrhea and abdominal cramping. This type of food poisoning is usually mild but can cause serious problems in older people. Rarely, certain strains of these bacteria produce a toxin that damages the intestine and causes an infection called necrotizing enteritis, which is often fatal.

Clostridium difficile-induced diarrhea and colitis (inflammation of the colon) can develop after antibiotics are taken to treat an infection (see page 176). Antibiotics may destroy some of the bacteria that normally reside in the intestine. If enough are destroyed, Clostridium difficile may overgrow. These bacteria may already be present in the intestine. Or people may get them from other people, pets, or the environment. Being very young or very old, staying in a hospital or nursing home, or having one or more severe disorders increases the risk of this disorder. When the bacteria overgrow, they release two toxins. One causes the intestine to produce fluids and abnormal membranes to form. The other damages the lining of the large intestine.

CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to determine whether abscesses are resolving. Surgery, with or without antibiotics, may be necessary, particularly if the infection affects critical areas such as the spine.

If actinomycosis is diagnosed early and treated appropriately, most people recover fully.

Anthrax

Anthrax is a potentially fatal infection with Bacillus anthracis, which may affect the skin, the lungs, or, rarely, the digestive (gastrointestinal) tract.

Infection in people usually results from skin contact but can result from inhaling spores or eating contaminated meat.

Infection in people usually results from skin contact but can result from inhaling spores or eating contaminated meat.

Symptoms include bumps and blisters (after skin contact), difficulty breathing and chest pain (after inhaling spores), and abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea (after eating contaminated meat).

Symptoms include bumps and blisters (after skin contact), difficulty breathing and chest pain (after inhaling spores), and abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea (after eating contaminated meat).

Symptoms suggest the infection, and identifying the bacteria in samples taken from infected tissue confirms the diagnosis.

Symptoms suggest the infection, and identifying the bacteria in samples taken from infected tissue confirms the diagnosis.

People at high risk of being exposed to anthrax are vaccinated.

People at high risk of being exposed to anthrax are vaccinated.

Antibiotics must be given soon after exposure to reduce the risk of dying.

Antibiotics must be given soon after exposure to reduce the risk of dying.

Anthrax can occur in wild and domestic animals that graze, such as cattle, sheep, and goats. Anthrax bacteria produce spores that can live for years in soil. Grazing animals become infected when they have contact with or consume the spores. Usually, anthrax is transmitted to people when they have contact with infected animals or animal products (such as wool, hides, and hair). Spores may remain in animal products for decades and are not easily killed by cold or heat. Even minimal contact is likely to result in infection. Although infection in people usually occurs through the skin, it can also result from inhaling spores or eating contaminated, undercooked meat. Anthrax cannot spread from person to person.

Anthrax is a potential biological weapon because anthrax spores can be spread through the air and inhaled.

Anthrax bacteria produce several toxins, which cause many of the symptoms.

Symptoms

Symptoms vary depending on how the infection is acquired: through the skin, through inhalation, or through the gastrointestinal tract.

Skin Anthrax: More than 95% of cases involve the skin. A painless, itchy, red-brown bump appears 1 to 12 days after exposure. The bump forms a blister, which eventually breaks open and forms a black scab (eschar), with swelling around it. Nearby lymph nodes may swell, and people may feel ill—sometimes with muscle aches, headache, fever, nausea, and vomiting. About 20% of untreated people die, but with treatment, death is rare.

Inhalation Anthrax (Woolsorter’s Disease): This form is the most serious. It results from inhaling anthrax spores. Spores may stay in the lungs for weeks but eventually enter white blood cells, where they germinate, and the resulting bacteria multiply and spread to lymph nodes in the chest. The bacteria produce toxins that make the lymph nodes swell, break down, and bleed, spreading the infection to nearby structures. Infected fluid accumulates in the space between the lungs and the chest wall.

Symptoms develop 1 to 43 days after exposure. Initially, they are vague and similar to those of influenza, with mild muscle aches, a low fever, chest discomfort, and a dry cough. After a few days, breathing suddenly becomes very difficult, and people have chest pain and a high fever with sweating. Blood pressure rapidly becomes dangerously low (causing shock), followed by coma. These severe symptoms probably result from a massive release of toxins. Infection of the brain and the fluid around the meninges (an infection called meningoencephalitis) frequently develops. Many people die 24 to 36 hours after severe symptoms start, even with early treatment. Without treatment, all people with inhalation anthrax die. In the 2001 outbreak in the United States, 5 of the 11 people treated for inhalation anthrax died.

Gastrointestinal Anthrax: Gastrointestinal anthrax is rare. When people eat contaminated meat, the bacteria grow in the mouth, throat, or intestine and release toxins that cause extensive bleeding and tissue death. People have a fever, a sore throat, a swollen neck, abdominal pain, and bloody diarrhea. They also vomit blood. At least half of untreated people with gastrointestinal anthrax die. With treatment, about half of people die.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Anthrax spores are not easily killed by cold or heat and can survive for decades.

Over 1.25 million people have received the anthrax vaccine without having a serious adverse reaction.

Diagnosis

Doctors suspect skin anthrax based on its typical appearance. Knowing that people have had contact with animals or animal products or were in an area where other people developed anthrax supports the diagnosis. If inhalation anthrax is suspected, chest x-ray and computed tomography (CT) are done.

Samples from infected skin, fluids around the lungs, or stool are removed and examined with a microscope or cultured (enabling bacteria, if present, to multiply). Anthrax bacteria, if present, can be readily identified. If people have inhalation anthrax, doctors may also take samples of the sputum or blood or do a spinal tap (lumbar puncture) to obtain a sample of the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord (cerebrospinal fluid). The samples are examined and analyzed. Blood tests may be done to check for fragments of the bacteria’s genetic material or antibodies to the toxins produced by the bacteria.

Prevention and Treatment

A vaccine against anthrax can be given to people at high risk of infection. Because of anthrax’s potential as a biological weapon, most members of the armed forces have been vaccinated. To be effective, the vaccine must be given in six doses. Despite widely publicized anxiety, over 1.25 million people have received the anthrax vaccine without having serious adverse reactions.

People who are exposed to anthrax may be given an antibiotic by mouth, usually ciprofloxacin or doxycycline or, if they cannot take these antibiotics, amoxicillin. The antibiotic is continued for 60 days to prevent the infection from developing. People may not need to take the antibiotic as long if they are also given several doses of anthrax vaccine.

OTHER BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

The longer treatment is delayed, the greater the risk of death. Thus, treatment is usually started as soon as anthrax is first suspected:

Skin anthrax is treated with ciprofloxacin or doxycycline given by mouth.

Skin anthrax is treated with ciprofloxacin or doxycycline given by mouth.

Inhalation or gastrointestinal anthrax is treated with a combination of antibiotics, including intravenous ciprofloxacin or doxycycline plus clindamycin, with or without rifampin. Corticosteroids may help relieve symptoms of inhalational anthrax.

Inhalation or gastrointestinal anthrax is treated with a combination of antibiotics, including intravenous ciprofloxacin or doxycycline plus clindamycin, with or without rifampin. Corticosteroids may help relieve symptoms of inhalational anthrax.

Bejel, Yaws, and Pinta

Bejel, yaws (frambesia), and pinta are infections caused by bacteria (called treponemal spirochetes) that are closely related to Treponema pallidum, which causes the sexually transmitted disease syphilis.

These very contagious infections are usually spread in areas where hygiene is poor.

These very contagious infections are usually spread in areas where hygiene is poor.

Bejel causes mouth sores and destructive lumps in bone, yaws causes skin sores and disfiguring growths on the legs and around the nose and mouth, and pinta causes itchy patches on the skin.

Bejel causes mouth sores and destructive lumps in bone, yaws causes skin sores and disfiguring growths on the legs and around the nose and mouth, and pinta causes itchy patches on the skin.

Doctors diagnose these infections when people have typical symptoms and have spent time in areas where the infections are common.

Doctors diagnose these infections when people have typical symptoms and have spent time in areas where the infections are common.

One injection of penicillin kills the bacteria.

One injection of penicillin kills the bacteria.

Bejel, yaws, and pinta are treponematoses, as is syphilis. Unlike syphilis, these infections are transmitted by nonsexual contact—chiefly between children living in conditions of poor hygiene. Bejel may be spread when eating utensils are shared.

Bejel occurs mainly in the hot arid countries of the eastern Mediterranean region and Saharan West Africa. Yaws occurs in humid equatorial countries. Pinta is common among the natives of Mexico, Central America, and South America. Bejel, yaws, and pinta rarely occur in the United States, except among immigrants from areas of the world where these diseases are common.

Symptoms

Yaws and pinta, like syphilis, begin with skin symptoms. Bejel begins with mouth sores. These symptoms subside, and after a period with few or no symptoms, new symptoms develop.

Bejel affects the mucous membranes of the mouth, then the skin and bones. The initial mouth sore may not be noticed. Moist patches then develop in the mouth. They resolve over a period of months to years. During this time, people have few or no symptoms. Then, lumps develop in long bones, mainly leg bones, and in the tissues around the mouth, nose, and roof of the mouth (palate). These lumps destroy tissue, causing bones to be deformed and disfiguring the face.

Yaws also affects the skin and bones. Several weeks after exposure to Treponema, yaws begins as a slightly raised sore at the site of infection, usually on a leg. The sore heals, but soft nodules (granulomas) form, then break open on the face, arms, legs, and buttocks. The granulomas heal slowly and may recur. Painful open sores on the soles of the feet (crab yaws) may develop, making walking difficult. Later, areas of the shinbones may be destroyed, and many other destructive, disfiguring growths (gangosa), especially around the nose, mouth, and palate, may develop.

Pinta affects only the skin. It begins as flat, itchy, reddened areas on the hands, feet, legs, arms, face, or neck. After several months, slate-blue patches develop in the same areas on both sides of the body. They develop where bones are close to skin, for example, on the elbow. Later, the patches lose their color. The affected skin on the palms and soles may thicken.

Diagnosis

Doctors make the diagnosis when typical symptoms appear in people who live in or have visited an area where such infections are common. Because the bacteria that cause these infections and the bacteria that cause syphilis are so similar, people who have one of these infections test positive for syphilis.

Treatment

A single injection of penicillin kills the bacteria. Then, the skin can heal. However, some scarring may remain, particularly if a lot of tissue has been destroyed. People who are allergic to penicillin are given tetracycline if they are 8 years old or older or erythromycin if they are pregnant or under 8 years old. These drugs are given by mouth.

Because the infections are very contagious, public health officials try to identify and treat infected people and their close contacts.

Campylobacter Infections

Several species of Campylobacter (most commonly Campylobacter jejuni) can infect the digestive tract, often causing diarrhea.

People can be infected when they consume contaminated food or drink or have contact with infected people or animals.

People can be infected when they consume contaminated food or drink or have contact with infected people or animals.

These infections cause diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever.

These infections cause diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever.

Identifying the bacteria in a stool sample confirms the diagnosis.

Identifying the bacteria in a stool sample confirms the diagnosis.

For some people, replacing lost fluids is all that is needed, but if symptoms are severe, antibiotics are also needed.

For some people, replacing lost fluids is all that is needed, but if symptoms are severe, antibiotics are also needed.

Campylobacter bacteria normally inhabit the digestive tract of many farm animals (including cattle, sheep, pigs, and fowl). The feces of these animals may contaminate water in lakes and streams. Meat (usually poultry) and unpasteurized milk may also be contaminated. People may be infected in several ways:

Eating or drinking contaminated (untreated) water, unpasteurized milk, undercooked meat (usually poultry), or food prepared on kitchen surfaces touched by contaminated meat

Eating or drinking contaminated (untreated) water, unpasteurized milk, undercooked meat (usually poultry), or food prepared on kitchen surfaces touched by contaminated meat

Contact with an infected person (particularly oral-anal sexual contact)

Contact with an infected person (particularly oral-anal sexual contact)

Contact with an infected animal

Contact with an infected animal

Campylobacter bacteria cause inflammation of the colon (colitis) that results in fever and diarrhea. These bacteria are a common cause of infectious diarrhea in the United States and among people who travel to countries where food or water may be contaminated. Infections are most commonly caused by Campylobacter jejuni.

Symptoms

Symptoms usually develop 2 to 5 days after exposure and continue for about 1 week. Symptoms of Campylobacter colitis include diarrhea, abdominal pain, and cramps, which may be severe. The diarrhea may be bloody and can be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and fever ranging from 100 to 104° F (38 to 40° C).

In some people with colitis, the bloodstream is temporarily infected (called bacteremia). This infection usually causes no symptoms or complications. However, the bloodstream is repeatedly or continuously infected in a few people. This type of bacteremia usually develops in people with a disorder that weakens the immune system, such as AIDS, diabetes, or cancer. This infection causes a long-lasting or recurring fever. Other symptoms develop as the bloodstream carries the infection to other structures, such as the following:

The space within the tissues covering the brain and spinal cord (causing meningitis)

The space within the tissues covering the brain and spinal cord (causing meningitis)

Bones (causing osteomyelitis)

Bones (causing osteomyelitis)

Joints (causing infectious arthritis)

Joints (causing infectious arthritis)

Rarely, heart valves (causing endocarditis)

Rarely, heart valves (causing endocarditis)

Guillain-Barré syndrome (see page 828) develops in about 1 of 1,000 of people with Campylobacter colitis. Guillain-Barré syndrome causes weakness or paralysis. Most people recover, but muscles may be greatly weakened. People may have difficulty breathing and need to use a mechanical ventilator. Weakness does not always completely resolve. Campylobacter colitis is thought to trigger about 20 to 40% of all cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Weeks to months after the diarrhea resolves, reactive arthritis may develop. Usually, the disorder causes inflammation and pain in the knees, hips, and Achilles tendon.

Diagnosis

Doctors may take a sample of stool and send it to a laboratory to grow (culture) the bacteria. However, stool is not always tested. Stool cultures take days to complete, and doctors do not usually need to know which bacteria caused the diarrhea to effectively treat it. If the bacteria are identified, they are tested to see which antibiotics are effective (a process called susceptibility testing).

If doctors suspect that the bloodstream is infected, they take a sample of blood to be cultured.

Treatment

Many people get better in a week or so without specific treatment. Some people require extra fluids intravenously or by mouth. People who have a high fever, bloody or severe diarrhea, or worsening symptoms may need to take azithromycin for 3 days or erythromycin for 5 days. Both drugs are taken by mouth. If the bloodstream is infected, antibiotics such as imipenem, gentamicin, or azithromycin are required for 2 to 4 weeks.

Cholera

Cholera is a serious infection of the intestine that is caused by the bacteria Vibrio cholerae and that causes severe diarrhea.

People are infected when they consume contaminated food, often seafood, or water.

People are infected when they consume contaminated food, often seafood, or water.

Cholera is rare except in areas where sanitation is inadequate.

Cholera is rare except in areas where sanitation is inadequate.

People have watery diarrhea and vomit, usually with no fever.

People have watery diarrhea and vomit, usually with no fever.

Identifying the bacteria in a stool sample confirms the diagnosis.

Identifying the bacteria in a stool sample confirms the diagnosis.

Replacing lost fluids and giving antibiotics treat the infection effectively.

Replacing lost fluids and giving antibiotics treat the infection effectively.

Several species of Vibrio bacteria cause diarrhea (see page 149). The most serious illness, cholera, is caused by Vibrio cholerae. Cholera may occur in large outbreaks.

Vibrio cholerae normally lives in aquatic environments along the coast. People acquire the infection by consuming contaminated water, seafood, or other foods. Once infected, people excrete the bacteria in stool. Thus, the infection can spread rapidly, particularly in areas where human waste is untreated.

Once common throughout the world, cholera is now largely confined to developing countries in the tropics and subtropics. It is common (endemic) in parts of Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and South and Central America. Small outbreaks have occurred in Europe, Japan, and Australia. In the United States, cholera can occur along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

In endemic areas, outbreaks usually occur when war or civil unrest disrupts public sanitation services. Infection is most common during warm months and among children. In newly affected areas, outbreaks may occur during any season and affect all ages equally.

For infection to develop, many bacteria must be consumed. Then, there may be too many for stomach acid to kill, and some bacteria can reach the small intestine, where they grow and produce a toxin. The toxin causes the small intestine to secrete enormous amounts of salt and water. The body loses this fluid as watery diarrhea. It is the loss of water and salt that causes death. The bacteria remain in the small intestine and do not invade tissues.

Because stomach acid kills the bacteria, people who produce less stomach acid are more likely to get cholera. Such people include young children, older people, and people taking drugs that reduce stomach acid, including proton pump inhibitors (such as omeprazole) and histamine-2 (H2) blockers (such as ranitidine). People living in endemic areas gradually acquire some immunity.

Symptoms

Most infected people have no symptoms. When symptoms occur, they begin 1 to 3 days after exposure, usually with sudden, painless, watery diarrhea and vomiting. Usually, fever is absent.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Without treatment, more than one half of people with severe cholera die.

Diarrhea and vomiting may be mild to severe. In severe infections, more than 1 quart of water and salts is lost per hour. The stool looks gray and has flecks of mucus in it. Within hours, dehydration can become severe, causing intense thirst, muscle cramps, and weakness. Very little urine is produced. The eyes may become sunken, and the skin on the fingers may become very wrinkled. If dehydration is not treated, loss of water and salts can lead to kidney failure, shock, coma, and death.

In people who survive, symptoms usually subside in 3 to 6 days. Most people are free of the bacteria in 2 weeks. The bacteria remain in a few people indefinitely without causing symptoms. Such people are called carriers.

Diagnosis

Doctors take a sample of stool or use a swab to obtain a sample from the rectum. It is sent to a laboratory where bacteria can be grown (cultured). Identifying Vibrio cholerae in the sample confirms the diagnosis.

Blood and urine tests to evaluate dehydration and kidney function are done.

Prevention

Purification of water supplies and appropriate disposal of human waste are essential. Other precautions include using boiled or chlorinated water and avoiding uncooked vegetables and undercooked fish and shellfish. Shellfish tend to carry other forms of Vibrio as well.

Several vaccines for cholera are available outside the United States. These vaccines provide only partial protection for a limited time and therefore are not generally recommended. New vaccines are currently being tested.

Treatment

Rapid replacement of lost body water and salts is lifesaving. Most people can be treated effectively with a solution given by mouth. These solutions are designed to replace the fluids the body has lost. For severely dehydrated people who cannot drink, a salt solution is given intravenously. In epidemics, if the intravenous solution is not available, people are sometimes given a salt solution through a tube inserted through the nose into the stomach. After enough fluids are replaced to relieve symptoms, people should drink at least enough of the salt solution to replace the fluids they have lost through diarrhea and vomiting. Solid foods can be eaten after vomiting stops and appetite returns.

People are usually given an antibiotic to reduce the severity of diarrhea and make it stop sooner. Also, people who take an antibiotic are slightly less likely to spread the infection during an outbreak. Tetracycline or doxycycline is effective in adults, unless the bacteria in the area are resistant to tetracycline. Then, ciprofloxacin can be used. Because tetracycline and doxycycline discolor the teeth in children under 8 years old, azithromycin, erythromycin, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is used instead.

More than 50% of untreated people with severe cholera die. Less than 1% of people who receive prompt, adequate fluid replacement die.

Gas Gangrene

Gas gangrene (clostridial myonecrosis) is a life-threatening infection of muscle tissue caused mainly by the anaerobic bacteria Clostridium perfringens and several other species of clostridia.

Gas gangrene can develop after certain types of surgery or injuries.

Gas gangrene can develop after certain types of surgery or injuries.

Blisters with gas bubbles form near the infected area, and the heartbeat and breathing become rapid.

Blisters with gas bubbles form near the infected area, and the heartbeat and breathing become rapid.

Symptoms suggest the diagnosis, and imaging tests or culture of a sample taken from infected tissue is usually done.

Symptoms suggest the diagnosis, and imaging tests or culture of a sample taken from infected tissue is usually done.

Treatment involves high doses of antibiotics and surgical removal of dead or infected tissue.

Treatment involves high doses of antibiotics and surgical removal of dead or infected tissue.

Gas gangrene is a fast-spreading clostridial infection of muscle tissue that, if untreated, quickly leads to death. The bacteria produce gas that becomes trapped in the infected tissue. Several thousand cases occur in the United States every year. Gas gangrene usually develops after injuries or surgery. High-risk injuries include wounds that

Are deep and severe

Are deep and severe

Involve muscle

Involve muscle

Are contaminated with dirt, decaying vegetable matter, or the person’s stool

Are contaminated with dirt, decaying vegetable matter, or the person’s stool

Contain crushed or dead tissue

Contain crushed or dead tissue

High-risk surgery includes operations on the colon or gallbladder.

Gas gangrene can occur when there is no injury or surgery—usually in people with colon cancer. People with open fractures and frostbite are also susceptible to gas gangrene. Gas gangrene may develop when a contaminated needle is used to inject an illegal drug into a muscle.

Symptoms

Gas gangrene causes severe pain in the infected area. Initially, the area is swollen and pale but eventually turns red, then bronze, and finally blackish green. Large blisters often form. Gas bubbles may be visible within the blister or may be felt under the skin, usually after the infection progresses. Fluids draining from the wound smell rotten (putrid).

People quickly become sweaty and very anxious. They may vomit. Heart rate and breathing often become rapid. In some people, the skin turns yellow, indicating jaundice. These effects are caused by toxins produced by the bacteria. Typically, people remain alert until late in the illness, when dangerously low blood pressure (shock) and coma develop. Kidney failure and death rapidly follow.

Without treatment, death occurs within 48 hours. Even with treatment, about one of eight people with an infected limb and about two of three people with infection in the torso die.

Diagnosis

The initial diagnosis is based on symptoms and results of a physical examination. X-rays are taken to check for gas bubbles in muscle tissue, or computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is done to check for signs of muscle involvement. These findings support the diagnosis. However, gas bubbles may also occur in other anaerobic infections.

Fluids from the wound are examined under a microscope to check for clostridia, and cultures are done to confirm their presence. However, not all people with clostridia have gas gangrene. Confirmation of the diagnosis may require exploratory surgery or removal of a tissue sample for examination under a microscope (biopsy) to check for characteristic changes in muscle.

Prevention and Treatment

Doctors do the following to prevent gas gangrene:

Clean wounds thoroughly

Clean wounds thoroughly

Remove foreign objects and dead tissue from wounds

Remove foreign objects and dead tissue from wounds

Give antibiotics intravenously before, during, and after abdominal surgery to prevent infection

Give antibiotics intravenously before, during, and after abdominal surgery to prevent infection

No vaccine can prevent clostridial infection.

If gas gangrene is suspected, treatment must begin immediately. High doses of antibiotics, typically penicillin and clindamycin, are given, and all dead and infected tissue is removed surgically. About one of five people with gas gangrene in a limb requires amputation. Treatment in a high-pressure oxygen (hyperbaric oxygen) chamber is of uncertain value, and such chambers are not always readily available.

Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Serratia Infections

Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Serratia are closely related gram-negative bacteria that occasionally infect people in hospitals or in long-term care facilities.

These bacteria may infect the urinary or respiratory tract, intravenous catheters used to give drugs or fluids, burns, wounds made during surgery, or the bloodstream.

These bacteria may infect the urinary or respiratory tract, intravenous catheters used to give drugs or fluids, burns, wounds made during surgery, or the bloodstream.

Identifying the bacteria in a sample taken from infected tissue confirms the diagnosis.

Identifying the bacteria in a sample taken from infected tissue confirms the diagnosis.

If the infection is acquired in the community, antibiotics can cure it, but if it is acquired in a health care facility, it is difficult to treat because bacteria tend to be resistant.

If the infection is acquired in the community, antibiotics can cure it, but if it is acquired in a health care facility, it is difficult to treat because bacteria tend to be resistant.

Klebsiella bacteria reside in the intestine of up to one third of healthy people. Enterobacter and Serratia bacteria usually reside outside the body, often in hospitals and long-term care facilities. People in such places can become infected.

These bacteria may infect different areas:

Urinary or respiratory tract

Urinary or respiratory tract

Catheters inserted into a vein (intravenous catheter), used to administer drugs or fluids

Catheters inserted into a vein (intravenous catheter), used to administer drugs or fluids

Burns

Burns

Wounds made during surgery

Wounds made during surgery

Bloodstream

Bloodstream

Rarely, Klebsiella bacteria cause pneumonia in people who live outside a health care facility (in the community), usually in alcoholics, older people, people with diabetes, or people with a weakened immune system. Typically, this severe infection causes cough, bringing up a sticky, dark brown or dark red sputum, and collections of pus (abscesses) in the lung or in the membrane between the lungs and chest wall (empyema).

One species of Klebsiella can cause inflammation of the colon (colitis) after antibiotics are taken. This disorder is called antibiotic-associated colitis. The antibiotics kill bacteria that normally reside in the intestine. Then Klebsiella bacteria are able to multiply and cause problems. However, this type of colitis usually results from toxins produced by Clostridium difficile (see page 176).

Diagnosis

Doctors suspect one of these infections in people at high risk of getting one, such as people who live in a long-term care facility or in a place when there was an outbreak. To confirm the diagnosis, doctors take a sample of sputum, lung secretions (obtained through a bronchoscope), blood, urine, or infected tissue. The sample is stained with Gram stain, cultured, and examined under a microscope. These bacteria can be readily identified.

Other tests depend on the type of infection. They may include imaging tests, such as ultrasonography, x-rays, and computed tomography (CT).

Bacteria identified in samples are tested to determine which antibiotics are likely to be effective (a process called susceptibility testing).

Treatment

If Klebsiella pneumonia is acquired in the community, antibiotics, usually a cephalosporin (such as ceftriaxone) or fluoroquinolone (such as levofloxacin), given intravenously, can cure it.

If an infection with any of these three bacteria is acquired in a health care facility, the infection is difficult to treat because bacteria acquired in such facilities are usually resistant to many antibiotics.

Escherichia coli Infections

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a group of gram-negative bacteria that normally reside in the intestine of healthy people, but some strains can cause infection.

People develop intestinal E. coli infections by eating contaminated food, touching infected animals, or swallowing contaminated water in a pool.

People develop intestinal E. coli infections by eating contaminated food, touching infected animals, or swallowing contaminated water in a pool.

Intestinal infections can cause diarrhea, sometimes severe or bloody, and abdominal pain.

Intestinal infections can cause diarrhea, sometimes severe or bloody, and abdominal pain.

Antibiotics can effectively treat E. coli infections outside the digestive tract and most intestinal infections but are not used to treat intestinal infections by one strain of these bacteria.

Antibiotics can effectively treat E. coli infections outside the digestive tract and most intestinal infections but are not used to treat intestinal infections by one strain of these bacteria.

Some strains of E. coli normally inhabit the digestive tract of healthy people. However, some strains of E. coli cause infection in the digestive tract and in other parts of the body, most commonly the urinary tract. E. coli is the most common cause of bladder infection in women. These bacteria can also cause infection of the prostate gland (prostatitis), gallbladder infection, infections that develop after appendicitis and diverticulitis, wound infections (including wounds made during surgery), infections in pressure sores, foot infections in people with diabetes, pneumonia, meningitis in newborns, and bloodstream infections. Many E. coli infections affecting areas outside the digestive tract develop in people who are debilitated, who are staying in a health care facility, or who have taken antibiotics.

One strain produces a toxin that causes brief watery diarrhea. This disorder (called traveler’s diarrhea—see page 152) usually occurs in travelers who consume contaminated food or water in areas where water is not adequately purified.

Another strain (E. coli O157:H7) produces a toxin that damages the colon and causes inflammation (colitis). People are usually infected with this strain by doing the following:

Eating contaminated ground beef that is not cooked thoroughly (one of the most common sources)

Eating contaminated ground beef that is not cooked thoroughly (one of the most common sources)

Going to a petting zoo and touching animals that carry the bacteria in their digestive tract

Going to a petting zoo and touching animals that carry the bacteria in their digestive tract

Eating ready-to-eat food (such as produce at salad bars) that was washed with contaminated water or contaminated by cattle manure

Eating ready-to-eat food (such as produce at salad bars) that was washed with contaminated water or contaminated by cattle manure

Swallowing inadequately chlorinated water that has been contaminated by the stool of infected people in swimming or wading pools

Swallowing inadequately chlorinated water that has been contaminated by the stool of infected people in swimming or wading pools

Inadequate hygiene, particularly common among young children in diapers, can easily spread the bacteria from person to person.

Symptoms

Symptoms depend on the part of the body affected and the strain of E. coli causing the infection.

In infections due to E. coli O157:H7, diarrhea begins about 3 days after exposure. Diarrhea becomes bloody about 1 to 3 days later. (This disease is sometimes called hemorrhagic colitis.) People usually have severe abdominal pain and diarrhea many times a day. They also often feel an urge to defecate but may not be able to. Most people do not have a fever. Because the infection is easily spread, people must often be hospitalized and isolated.

The diarrhea resolves on its own in 85% of people. However, in about 15% of children and fewer older people, red blood cells are destroyed and kidney failure occurs about 1 week after symptoms begin. This complication (called hemolytic-uremic syndrome—see page 1042) is a common cause of chronic kidney disease in children.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

E. coli is the most common cause of bladder infection in women.

Diagnosis

Samples of blood, stool, sometimes urine, or other infected material are taken and sent to a laboratory to grow (culture) the bacteria. Identifying the bacteria in the sample confirms the diagnosis. If the bacteria are identified, they may be tested to see which antibiotics are effective (a process called susceptibility testing).

If E. coli O157:H7 is detected, blood tests must be done frequently to check for hemolytic-uremic syndrome.

Treatment

For traveler’s diarrhea, loperamide can be given to slow movement of food through the intestine and thus help control diarrhea. Antibiotics (such as azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, or rifaximin) can also be given to end symptoms more quickly.

Many people with diarrhea due to E. coli O157:H7 need to be given fluids containing salts intravenously. This infection is not treated with loperamide or antibiotics. Antibiotics may make diarrhea worse and increase the risk of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. If hemolytic-uremic syndrome develops, people are admitted to an intensive care unit and may require hemodialysis.

Many other E. coli infections, usually bladder or other urinary tract infections, are treated with antibiotics, such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or a fluoroquinolone. However, many bacteria, particularly those acquired in a health care facility, are resistant to these antibiotics. For more serious infections, antibiotics that are effective against many different bacteria (broad-spectrum antibiotics) may be used. Several antibiotics may be used together until doctors get the test results indicating which antibiotics are likely to be effective.

Haemophilus influenzae Infections

Haemophilus influenzae can cause infection in the respiratory tract, which can spread to other organs.

Infection is spread through sneezing, coughing, or touching.

Infection is spread through sneezing, coughing, or touching.

The bacteria can cause middle ear infections, sinusitis, and more serious infections, including meningitis and epiglottitis.

The bacteria can cause middle ear infections, sinusitis, and more serious infections, including meningitis and epiglottitis.

Identifying the bacteria in a sample taken from infected tissue confirms the diagnosis.

Identifying the bacteria in a sample taken from infected tissue confirms the diagnosis.

Children are routinely given a vaccine that effectively prevents infections due to Haemophilus influenzae type b.

Children are routinely given a vaccine that effectively prevents infections due to Haemophilus influenzae type b.

Infections are treated with antibiotics given by mouth or, for serious infections, intravenously.

Infections are treated with antibiotics given by mouth or, for serious infections, intravenously.

Many species of Haemophilus normally reside in the upper airways of children and adults and rarely cause disease. One species causes chancroid, a sexually transmitted disease. Other species cause infections of heart valves (endocarditis) and, rarely, collections of pus (abscesses) in the brain, lungs, and liver. The species responsible for the most infections is Haemophilus influenzae.

Haemophilus influenzae can cause infections in children and sometimes in adults who have a chronic lung disorder or a weakened immune system. Infection is spread by sneezing, coughing, or touching infected people. One type of Haemophilus influenzae, called type b, is more likely to cause serious infections.

In children, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) can spread through the bloodstream (causing bacteremia) and infect the joints, bones, lungs, skin of the face and neck, eyes, urinary tract, and other organs. The bacteria may cause two severe, often fatal infections: meningitis and epiglottitis (infection of the flap of tissue over the voice box). Some strains cause infection of the middle ear in children, the sinuses in children and adults, and the lungs in adults, especially those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or AIDS.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Symptoms vary depending on the part of the body affected.

To diagnose the infection, doctors take a sample of blood, pus, or other body fluids and send it to a laboratory to grow (culture) the bacteria. If people have symptoms of meningitis, doctors do a spinal tap (lumbar puncture) to obtain a sample of the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord (cerebrospinal fluid). Identifying the bacteria in a sample confirms the diagnosis.

Prevention and Treatment

Children are routinely vaccinated against Haemophilus influenzae type b. The vaccine is very effective, especially in preventing meningitis, epiglottitis, and bacteremia.

Treatment of meningitis must begin as soon as possible. An antibiotic—usually, ceftriaxone or cefotaxime—is given intravenously. Corticosteroids may help prevent brain damage.

Epiglottitis must also be treated as soon as possible. People may need help breathing. An artificial airway, such as a breathing tube, may be inserted, or rarely, an opening may be made in the windpipe (a procedure called tracheostomy). The antibiotic rifampin is used because it can eradicate the bacteria from the throat. People are given this antibiotic before they are discharged from the hospital.

If the household of a person with a serious Haemophilus influenzae type b infection includes a child who is under 4 years old and is not fully immunized against Haemophilus influenzae type b, the child should be vaccinated. Also, all members of the household, except pregnant women, should be given an antibiotic, such as rifampin, by mouth to prevent infection.

Other Haemophilus influenzae infections are treated with various antibiotics given by mouth. They include amoxicillin-clavulanate, azithromycin, cephalosporins, clarithromycin, fluoroquinolones, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a potentially serious disorder caused by Leptospira bacteria.

Most people are infected through contact with contaminated soil or water during outdoor activities.

Most people are infected through contact with contaminated soil or water during outdoor activities.

Fever, headache, and other symptoms occur in two phases, separated by a few days.

Fever, headache, and other symptoms occur in two phases, separated by a few days.

A severe, potentially fatal form damages many organs, including the liver and kidneys.

A severe, potentially fatal form damages many organs, including the liver and kidneys.

Detecting antibodies against the bacteria in blood or identifying the bacteria in a sample taken from infected tissue confirms the diagnosis.

Detecting antibodies against the bacteria in blood or identifying the bacteria in a sample taken from infected tissue confirms the diagnosis.

Antibiotics and sometimes fluids containing salts are given, but people with the severe form may require transfusions and hemodialysis.

Antibiotics and sometimes fluids containing salts are given, but people with the severe form may require transfusions and hemodialysis.

Leptospirosis occurs in many wild and domestic animals. Some animals act as carriers and pass the bacteria in their urine. Others become ill and die. People acquire these infections directly through infected animals or indirectly through soil or water contaminated by urine from an infected animal.

Leptospirosis is an occupational disease of farmers and sewer and slaughterhouse workers. However, most people become infected during outdoor activities when they come in contact with contaminated soil or water, particularly while swimming or wading. The 40 to 100 infections reported every year in the United States occur mainly in the late summer and early fall. Because mild leptospirosis typically causes vague, flu-like symptoms that go away on their own, many infections are probably unreported.

Symptoms

In about 90% of infected people, symptoms are mild. In the rest, the disorder involves many organs. This potentially fatal form of leptospirosis is called Weil’s syndrome.

Leptospirosis usually occurs in two phases:

First phase: About 2 to 20 days after infection occurs, fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, severe muscle aches in the calves and back, and chills occur suddenly. The eyes usually become very red on the third or fourth day. Some people cough, occasionally bringing up blood, and have chest pain. Most people recover within 1 week.

First phase: About 2 to 20 days after infection occurs, fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, severe muscle aches in the calves and back, and chills occur suddenly. The eyes usually become very red on the third or fourth day. Some people cough, occasionally bringing up blood, and have chest pain. Most people recover within 1 week.

Second (immune) phase: In some people, symptoms recur a few days later. They result from inflammation caused by the immune system as it eliminates the bacteria from the body. The fever returns, and the space within the tissues covering the brain and spinal cord (meninges) often becomes inflamed. This inflammation (meningitis) causes a stiff neck and headache.

Second (immune) phase: In some people, symptoms recur a few days later. They result from inflammation caused by the immune system as it eliminates the bacteria from the body. The fever returns, and the space within the tissues covering the brain and spinal cord (meninges) often becomes inflamed. This inflammation (meningitis) causes a stiff neck and headache.

Weil’s Syndrome: This form can occur during the second phase. It causes jaundice (yellowish discoloration of the skin and whites of the eyes), kidney failure, and a tendency to bleed. People may have nosebleeds or cough up blood, or bleeding may occur within tissues in the skin, lungs, and, less commonly, digestive tract. Anemia can develop. Several organs such as the heart, lungs, and kidneys may stop functioning.

Most people who do not develop jaundice recover. About 5 to 10% of people with jaundice (which indicates liver damage) die. The death rate is probably higher in people with Weil’s syndrome and people over 60. If leptospirosis develops during early pregnancy, the risk of miscarriage is increased.

Diagnosis

To confirm the diagnosis, doctors take a sample of blood and urine. These samples are analyzed. If people have symptoms of meningitis, doctors do a spinal tap (lumbar puncture) to obtain a sample of the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord (cerebrospinal fluid). Usually, several samples are taken over several weeks. These samples are sent to a laboratory to grow (culture) the bacteria.

Identifying the bacteria in cultures or, more commonly, detecting antibodies against the bacteria in blood confirms the diagnosis.

Prevention and Treatment

The antibiotic doxycycline can prevent leptospirosis. It is given to people who were exposed to the bacteria at the same time as people who have been infected.

Mild infections are treated with antibiotics such as amoxicillin or doxycycline, given by mouth. For severe infections, antibiotics such as penicillin, doxycycline, or erythromycin may be given intravenously. Fluids containing salts may also be given. People with the infection do not have to be isolated, but care must be taken when handling and disposing of their urine.

People with Weil’s syndrome may need blood transfusions and hemodialysis.

Listeriosis

Listeriosis is infection caused by the gram-positive bacteria Listeria monocytogenes.

People may consume the bacteria in commercially prepared foods that require no further cooking.

People may consume the bacteria in commercially prepared foods that require no further cooking.

People have fever, chills, and muscle aches plus nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

People have fever, chills, and muscle aches plus nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

Identifying the bacteria in a sample of blood or cerebrospinal fluid confirms the diagnosis.

Identifying the bacteria in a sample of blood or cerebrospinal fluid confirms the diagnosis.

Antibiotics can cure the infection.

Antibiotics can cure the infection.

Listeria monocytogenes resides in the intestine of many animals worldwide. Most cases of listeriosis result from eating contaminated food. The bacteria grow in food at refrigerator temperatures and survive in the freezer. Pasteurization of dairy products destroys the bacteria unless many bacteria are present. Adequate cooking or reheating of food kills the bacteria. However, they can reside in food-filled cracks and inaccessible areas in commercial food preparation facilities and recontaminate food. If the food requires no further cooking once purchased, the bacteria that remain are consumed with the food. They can grow in a refrigerated, packaged, ready-to-eat product without changing the food’s taste or smell. Foods involved in previous outbreaks of listerosis include soft cheeses (such as Latin American white cheeses, feta, Brie, and Camembert), delicatessen salads (such as cole slaw), unpasteurized milk, cold cuts, turkey franks, other hot dogs, shrimp, and undercooked chicken.

The bacteria sometimes enter the bloodstream from the intestine and spread, causing invasive listeriosis. Bacteria may spread to the space within the tissues covering the brain and spinal cord (causing meningitis), the eyes, heart valves (causing endocarditis), or, in pregnant women, the uterus. Collections of pus (abscesses) may form in the brain and spinal cord. In the United States, invasive listeriosis develops in only about 2,500 people each year but is fatal in 20 to 30%. It is more common among pregnant women, newborns, people aged 60 or older, and people with a weakened immune system, such as those with human immunodeficiency (HIV) infection. About one third of cases occur in pregnant women.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Pregnant women are particularly susceptible to listeriosis, which can harm the fetus.

Symptoms

People typically have chills, fever, and muscle aches (resembling the flu), with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Usually, symptoms resolve in 5 to 10 days.

If invasive listeriosis develops, symptoms vary depending on the area infected. If meningitis develops, people have a headache and a stiff neck. They may become confused and lose their balance. If the uterus or placenta is infected in a pregnant woman, spontaneous abortion or stillbirth may result. Or the newborn may have a bloodstream infection (sepsis) or meningitis. About one half of newborns infected near or at the end of the pregnancy die.

Diagnosis

A sample of blood is withdrawn. If people have symptoms of meningitis, a spinal tap (lumbar puncture) is done to obtain a sample of the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord (cerebrospinal fluid). The samples are sent to a laboratory to grow (culture) the bacteria. Identifying the bacteria in the sample confirms the diagnosis.

Treatment

The antibiotic ampicillin or, for people who are allergic to penicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole usually cures listeriosis. These antibiotics are given intravenously. If the heart valves are infected, a second antibiotic (such as gentamicin) may be given at the same time.

Eye infections can be treated with erythromycin, given by mouth, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, given intravenously.

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi, which is usually transmitted to people by deer ticks.

Most people are infected when they go outdoors in wooded areas where the disease is common.

Most people are infected when they go outdoors in wooded areas where the disease is common.

Typically, a large, red spot appears at the site of the bite and slowly enlarges, often surrounded by several red rings.

Typically, a large, red spot appears at the site of the bite and slowly enlarges, often surrounded by several red rings.

Untreated, the disease can cause fever, muscle aches, swollen joints, and eventually problems related to brain and nerve malfunction.

Untreated, the disease can cause fever, muscle aches, swollen joints, and eventually problems related to brain and nerve malfunction.

The diagnosis is based on typical symptoms, opportunity for exposure, and blood tests to detect antibodies to the bacteria.

The diagnosis is based on typical symptoms, opportunity for exposure, and blood tests to detect antibodies to the bacteria.

Taking antibiotics usually cures the disease, but some symptoms, such as joint pain, may persist.

Taking antibiotics usually cures the disease, but some symptoms, such as joint pain, may persist.

Lyme disease was recognized and named in 1975 when a cluster of cases occurred in Lyme, Connecticut. It is now the most common insect-borne infection in the United States. It occurs in 49 states. About 80% of the cases occur along the northeastern coast from Massachusetts to Maryland. Most of the remaining reported cases occur in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the coastal regions of northern California and Oregon. Lyme disease also occurs in Europe, China, Japan, Australia, and the former Soviet Union.

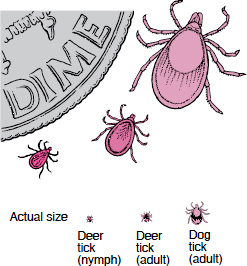

Usually, people get Lyme disease in the summer and early fall. Children and young adults who live in wooded areas are most often infected.

The bacteria that cause Lyme disease are transmitted by the deer tick (Ixodes), so named because the adult ticks often feed on the blood of deer. Young deer ticks (larvae and nymphs) feed on the blood of rodents, particularly the white-footed mouse, which is a carrier of Lyme disease bacteria. Ticks are usually in the nymph stage when they infect people. Deer do not carry or transmit Lyme disease bacteria. They are only a source of blood for adult ticks.

Preventing Tick Bites

People can reduce their chances of picking up or being bitten by a tick by doing the following:

Staying on paths and trails when walking in wooded areas

Staying on paths and trails when walking in wooded areas

Walking in the center of trails to avoid brushing up against bushes and weeds

Walking in the center of trails to avoid brushing up against bushes and weeds

Not sitting on the ground or on stone walls

Not sitting on the ground or on stone walls

Wearing long-sleeved shirts

Wearing long-sleeved shirts

Wearing long pants and tucking them into boots or socks

Wearing long pants and tucking them into boots or socks

Wearing light-colored clothing, which makes ticks easier to see

Wearing light-colored clothing, which makes ticks easier to see

Applying an insect repellent containing diethyltoluamide (DEET) to the skin

Applying an insect repellent containing diethyltoluamide (DEET) to the skin

Applying an insect repellent containing permethrin to clothing

Applying an insect repellent containing permethrin to clothing

Usually, Lyme disease is transmitted by young deer ticks (nymphs), which are very small, much smaller than dog ticks. So people who may have been exposed to ticks should check the whole body very carefully, especially hairy areas, every day. Inspection is effective because ticks must be attached for more than a day to transmit Lyme disease.

To remove a tick, people should use fine-pointed tweezers to grasp the tick by the head or mouthparts right where they enter the skin and should gradually pull the tick straight off. The tick’s body should not be grasped or squeezed. Petroleum jelly, alcohol, lit matches, or any other irritants should not be used.

The bacteria that cause Lyme disease are transmitted to people when an infected tick bites and stays attached for one or two days. Brief periods of attachment rarely transmit disease. At first, the bacteria multiply at the site of the tick bite. After 3 to 32 days, the bacteria migrate from the site of the bite into the surrounding skin, causing a rash (erythema migrans). The bacteria enter the bloodstream and spread to other organs, such as the skin in other areas of the body and the heart, nervous system, and joints.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Usually, people get Lyme disease only if a tick remains attached to them for at least a day.

Symptoms

Lyme disease has three stages: early localized, early disseminated (widespread), and late. The early and late stages are usually separated by a period without symptoms.

Early-Localized Stage: Typically, a large, raised, red spot (erythema migrans) appears at the site of the bite, usually on the thigh, buttock, or trunk or in the armpit. Usually, the spot slowly expands to a diameter of 6 inches (15 centimeters), often clearing in the center, resulting in several concentric red rings. Although erythema migrans does not itch or hurt, it may be warm to the touch. The spot usually disappears after about 3 to 4 weeks. About 25% of infected people never develop—or at least never notice—the characteristic red spot.

Early-Disseminated Stage: This stage begins when the bacteria spread through the body. Fatigue, chills, fever, headaches, stiff neck, muscle aches, and painful, swollen joints are common. In nearly half of people, more, usually smaller erythema migrans spots appear on other parts of the body. Less commonly, people have a backache, nausea, vomiting, sore throat, swollen lymph nodes, and an enlarged spleen. Although most symptoms come and go, feelings of illness and fatigue may persist for weeks. These symptoms are often mistaken for influenza or common viral infections, especially if erythema migrans is not present.

Sometimes more serious symptoms develop. The nervous system is affected in about 15% of people. The most common problems are headache, stiff neck, meningitis, and Bell’s palsy, which causes weakness on one or occasionally both sides of the face. These problems may last for months. Nerve pain and weakness may develop in other areas and persist longer. About 8% of infected people have irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias) and inflammation of heart tissue (myocarditis) and the sac around the heart (pericarditis) with chest pain. Irregular heartbeats may cause palpitations, light-headedness, or fainting.

Late Stage: If the initial infection is untreated, other problems develop months to years later. Arthritis develops in more than half of people, usually within several months. Swelling and pain typically recur in a few large joints, especially the knee, for several years. The knees are commonly more swollen than painful, often hot to the touch, and, rarely, red. Cysts may develop and rupture behind the knees, suddenly increasing the pain. In about 10% of people with arthritis, knee problems last longer than 6 months.

A few people develop abnormalities related to brain and nerve malfunction. Mood, speech, memory, and sleep may be affected. Some people have numbness or shooting pains in the back, legs, and arms.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually based on typical symptoms (particularly erythema migrans), opportunity for exposure (living in or visiting an area where Lyme disease is common), and test results.

Usually, doctors use tests that measure antibodies to the bacteria in blood. However, antibodies may be absent if the test is done during the first several weeks of infection or if antibiotics are given before antibodies develop. Antibodies develop in more than 95% of people who have had the infection for at least a month, particularly if they have not taken antibiotics. Once antibodies develop, they persist permanently. Thus, antibodies may be present after Lyme disease has resolved.

Interpreting the results of blood tests is difficult. The uncertainty causes several problems. For example, in areas where Lyme disease is common, many people who have painful joints, trouble concentrating, or persistent fatigue worry that they have late-stage Lyme disease, even though they never had a rash or any other symptoms of early-stage Lyme disease. Usually, Lyme disease is not the cause. But they may have antibodies for the bacteria because they were infected years before and the antibodies persist indefinitely. Thus, if a doctor treats people based solely on results of antibody tests, many people who do not have Lyme disease are treated with long, useless courses of antibiotics.

Cultures are not helpful because Borrelia burg-dorferi is difficult to grow in the laboratory.

Sometimes doctors insert a needle into a joint to take a sample of joint fluid or do a spinal tap (lumbar puncture) to take a sample of the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord (cerebrospinal fluid). Fragments of the bacteria’s genetic material may be present.

Treatment

If people are bitten by a tick but have no rash or other symptoms, antibiotics are usually used only if they can be given within 72 hours after an engorged tick is found attached. These people may be given one dose of doxycycline by mouth to prevent Lyme disease from developing.

Although all stages of Lyme disease respond to antibiotics, early treatment is more likely to prevent complications. Antibiotics such as doxycycline, amoxicillin, cefuroxime, or azithromycin, taken by mouth for 2 weeks, are effective during the early stages of the disease. They can also help treat a type of arrhythmia called first-degree heart block and probably Bell’s palsy. Doxycycline is not given to children under 9 years old or to pregnant women.

For arthritis, antibiotics such as amoxicillin or doxycycline are given by mouth for 30 to 60 days, or ceftriaxone or penicillin is given intravenously for 2 to 4 weeks.