CHAPTER 245

Breast Disorders

Breast disorders may be noncancerous (benign) or cancerous (malignant). Most are noncancerous and not life threatening. Often, they do not require treatment. In contrast, breast cancer can mean loss of a breast or of life. Thus, for many women, breast cancer is their worst fear. However, potential problems can be detected early when women regularly examine their breasts themselves, are examined regularly by their doctor, and have mammograms as recommended. Early detection of breast cancer is essential to successful treatment.

Symptoms

Symptoms related to the breast are common. They include breast pain, lumps, and a discharge from the nipple. The breast’s skin may become pitted, puckered, or dimpled. Breast symptoms do not necessarily mean that a woman has breast cancer or another serious disorder. For example, monthly breast tenderness that is related to hormonal changes before a menstrual period does not indicate a serious disorder. However, women should examine their breasts once a month (see art on page 1552) and should see their doctor if they observe any change in a breast, particularly any of the following:

A lump that feels distinctly different from other breast tissue or that does not go away

A lump that feels distinctly different from other breast tissue or that does not go away

Swelling that does not go away

Swelling that does not go away

Pitting, puckering, or dimpling in the skin of the breast

Pitting, puckering, or dimpling in the skin of the breast

Scaly skin around the nipple

Scaly skin around the nipple

Inside the Breast

The female breast is composed of milk-producing glands (lobules) surrounded by fatty tissue and some connective tissue. Milk secreted by the glands flows through ducts to the nipple. Around the nipple is an area of pigmented skin called the areola.

Changes in the shape of the breast

Changes in the shape of the breast

Changes in the nipple, such as turning inward

Changes in the nipple, such as turning inward

Discharge from the nipple, especially if it is bloody

Discharge from the nipple, especially if it is bloody

Breast Pain: Many women experience breast pain (mastalgia). Causes include the following:

Hormonal changes

Hormonal changes

Cysts

Cysts

Infection

Infection

Fibrocystic changes

Fibrocystic changes

Very rarely, cancer

Very rarely, cancer

Breast pain may be related to hormonal changes. For example, it may occur during or just before a menstrual period (as part of the premenstrual syndrome) or early in pregnancy. Women who take oral contraceptives or who take hormone therapy after menopause commonly have this kind of pain. When levels of the female hormones estrogen and progesterone increase (during the menstrual cycle or pregnancy or because of therapy), they cause the milk glands and ducts of the breasts to enlarge and the breasts to retain fluid. The breasts then become swollen and sometimes painful. Such pain is usually diffuse, making the breasts tender to touch. Pain related to the menstrual period may come and go for months or years.

Other causes of breast pain include breast cysts, infections, and abscesses. In these cases, breast pain is usually felt in a particular place. Fibrocystic changes (formerly called fibrocystic breast disease) may include breast pain. Pain is the first symptom in only about 5% of women with breast cancer. Breast pain that persists for more than 1 month should be evaluated.

Mild breast pain usually disappears eventually, even without treatment. Pain that occurs during menstrual periods can usually be relieved by taking acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID).

For certain types of severe pain, danazol (a synthetic hormone related to testosterone) or tamoxifen (a drug used to treat breast cancer) may be used. These drugs inhibit the activity of estrogen and progesterone, which can make the breasts swell and be painful. Because long-term use of these drugs has side effects, the drugs are usually given for only a short time. Tamoxifen has fewer side effects than danazol. Tamoxifen is used mainly in postmenopausal women but may benefit younger women.

If a specific disorder is identified as the cause, the disorder is treated. For example, if a cyst is the cause, draining the fluid from the cyst usually relieves the pain.

Breast Lumps: Lumps in the breasts are relatively common and are usually not cancerous. Causes include the following:

Cysts

Cysts

Fibroadenomas

Fibroadenomas

Scar tissue

Scar tissue

Rarely, cancer

Rarely, cancer

But because lumps may be cancerous, they should be evaluated by a doctor without delay. Lumps may be fluid-filled sacs (cysts) or solid masses, which are usually fibroadenomas (see page 1548).

Other solid breast lumps include hardened glandular tissue (sclerosing adenosis) and scar tissue that has replaced injured fatty tissue (fat necrosis). Neither is cancerous. However, these lumps can be diagnosed only by biopsy. They require no treatment.

Nipple Discharge: One or both nipples sometimes discharge a fluid. A nipple discharge occurs normally during milk production (lactation) after childbirth. Or it can occur when the nipple is mechanically stimulated by fondling, suckling, or irritation from clothing or when women are sexually aroused. During the last weeks of pregnancy, the breasts may produce a milky discharge (colostrum). Stress can also result in a nipple discharge.

A normal nipple discharge is a thin, cloudy, whitish or almost clear fluid that is not sticky. However, during pregnancy or breastfeeding, a slightly bloody discharge sometimes occurs normally.

Several disorders can cause an abnormal discharge. Abnormal discharges vary in appearance depending on the cause:

A bloody discharge may be caused by a noncancerous breast tumor (such as a tumor in a milk duct, called an intraductal papilloma) or, less commonly, by breast cancer. Among women who have an abnormal discharge, breast cancer is the cause in fewer than 10%.

A bloody discharge may be caused by a noncancerous breast tumor (such as a tumor in a milk duct, called an intraductal papilloma) or, less commonly, by breast cancer. Among women who have an abnormal discharge, breast cancer is the cause in fewer than 10%.

A greenish discharge is usually due to a fibroadenoma, which is a noncancerous solid lump.

A greenish discharge is usually due to a fibroadenoma, which is a noncancerous solid lump.

A discharge that contains pus and smells foul may result from a breast infection.

A discharge that contains pus and smells foul may result from a breast infection.

A large amount of milky discharge in women who are not breastfeeding may represent galactorrhea (see page 989).

A large amount of milky discharge in women who are not breastfeeding may represent galactorrhea (see page 989).

Disorders of the pituitary gland or brain, encephalitis (a brain infection), an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism), kidney or liver disorders, and head or chest injuries can also cause a nipple discharge.

Taking certain drugs can cause a nipple discharge. These drugs include opioids, certain drugs used to treat stomach disorders (such as cimetidine, ranitidine, and metoclopramide), certain antidepressants, and certain antihypertensives (such as methyldopa, reserpine, and verapamil).

A discharge from one breast is likely to be caused by a problem with that breast, such as a noncancerous or cancerous breast tumor. A discharge from both breasts is more likely to be caused by a problem outside the breast, such as a hormonal disorder or use of certain drugs.

WHAT CAUSES NIPPLE DISCHARGE?

| TYPE | EXAMPLES |

| Breast disorders | Breast cancer Breast infections or abscesses Fibrocystic changes Most commonly, noncancerous milk duct tumors (intraductal papilloma) |

| Other disorders | Brain disorders Encephalitis (a brain infection) Head or chest injuries Kidney disorders Liver disorders Pituitary gland disorders An underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism) |

| Drugs | Certain antidepressants Certain antihypertensives, such as methyldopa, reserpine, and verapamil Older antipsychotic drugs such as chlorpromazine Certain drugs used to treat stomach disorders, such as cimetidine, ranitidine, and metoclopramide Opioids Oral contraceptives |

If a nipple discharge persists for more than one menstrual cycle or seems unusual, women should see a doctor. Postmenopausal women who have a nipple discharge should see a doctor promptly. Doctors examine the breast, looking for abnormalities. Tests that may be done include ultrasonography of the breast, mammography, blood tests to measure hormone levels, and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head. Women are asked for a complete list of drugs they are taking. Sometimes a specific cause cannot be identified.

If a disorder is the cause, the disorder is treated. If a noncancerous tumor is causing a discharge from one breast, the duct that the discharge is coming from may be removed.

Breast Cysts

Breast cysts are fluid-filled sacs that develop in the breast.

Breast cysts are common. In some women, many cysts develop frequently, sometimes with other fibrocystic changes. The cause of breast cysts is unknown, although injury may be involved. Breast cysts can be tiny or several inches in diameter.

Cysts sometimes cause breast pain. To relieve the pain, a doctor may drain fluid from the cyst with a thin needle. Sometimes the fluid is examined under a microscope to check for cancer. The color and amount are noted. If the fluid is bloody, brown, or cloudy or if the cyst does not disappear or reappears within 12 weeks after it is drained, the entire cyst is removed surgically because cancer in the cyst wall, although rare, is possible.

Fibroadenomas

Fibroadenomas are small, solid, rubbery noncancerous lumps composed of fibrous and glandular tissue.

Fibroadenomas usually appear in young women, including teenagers. The cause is unknown.

The lumps are easy to move and have clearly defined edges that can be felt during self-examination. They may feel like small, slippery marbles. These characteristics indicate to a doctor that the lumps are less likely to be cancerous. Nonetheless, to be sure that they are not cancerous, the doctor usually removes the lumps. A local anesthetic is used.

Fibroadenomas often recur. If several lumps have been removed and found to be noncancerous, a woman and her doctor may decide against removing new lumps that develop.

Fibrocystic Changes

Fibrocystic changes (formerly called fibrocystic breast disease) include breast pain, cysts, and lumpiness that are not due to cancer.

Most women have some general lumpiness in the breasts, usually in the upper outer part, near the armpit. In the United States, many women have this kind of lumpiness, breast pain, breast cysts, or some combination of these symptoms—a condition called fibrocystic changes.

Normally, the levels of the female hormones estrogen and progesterone fluctuate during the menstrual cycle. Milk glands and ducts enlarge and breasts retain fluid when levels increase, and the breasts return to normal when levels decrease. (These fluctuations partly explain why breasts are swollen and more sensitive during a particular time of each menstrual cycle.) Fibrocystic changes may result from repeated stimulation by these hormones. The following increase the risk of these changes:

Starting to menstruate at an early age

Starting to menstruate at an early age

Having a first baby at age 30 or later

Having a first baby at age 30 or later

Never having a baby

Never having a baby

Other breast disorders, such as infections, can cause these changes.

The lumpy areas may enlarge, causing a feeling of heaviness, discomfort, tenderness to the touch, or a burning pain. The symptoms tend to subside after menopause.

Most fibrocystic changes do not increase the risk of breast cancer, but a few of them do, although only slightly. These changes typically require a biopsy to rule out cancer and may make the breasts appear dense on mammograms. They include the following:

Complex fibroadenoma: The cells that line the breast ducts and connective tissue in the breasts form a benign tumor with many types of changes in tissue.

Complex fibroadenoma: The cells that line the breast ducts and connective tissue in the breasts form a benign tumor with many types of changes in tissue.

Moderate or severe hyperplasia: The cells that line the milk glands or ducts multiply too much, and their arrangement may become distorted (called atypical hyperplasia).

Moderate or severe hyperplasia: The cells that line the milk glands or ducts multiply too much, and their arrangement may become distorted (called atypical hyperplasia).

Sclerosing adenosis: The number of milk glands increases, and scar tissue forms, distorting the arrangement of milk glands.

Sclerosing adenosis: The number of milk glands increases, and scar tissue forms, distorting the arrangement of milk glands.

Papilloma: Noncancerous, finger-like tumors develop in the cells that line the breast ducts.

Papilloma: Noncancerous, finger-like tumors develop in the cells that line the breast ducts.

Fibrocystic changes may make breast cancer more difficult to detect.

Treatment

Lumps, usually only one lump at a time, may be removed, and a biopsy may be done to rule out cancer. Sometimes the biopsy sample can be withdrawn with a needle, but sometimes it must be removed surgically.

Sometimes cysts are drained, but they tend to recur. No specific treatment is available or required, but certain measures may help relieve symptoms:

Wearing a soft, supportive brassiere

Wearing a soft, supportive brassiere

Taking pain relievers

Taking pain relievers

If symptoms are severe, doctors may prescribe drugs, such as danazol (a synthetic male hormone) or tamoxifen (which blocks the effects of estrogen). Because side effects can occur with long-term use, the drugs are usually given for only a short time. Tamoxifen has fewer side effects than danazol.

Breast Infection and Abscess

A breast infection (mastitis) is rare, except around the time of childbirth (see page 1671) or after an injury or surgery. The most common symptom is a swollen, red area that feels warm and tender. An uncommon type of breast cancer called inflammatory breast cancer (see page 1551) can cause similar symptoms. A breast infection is treated with antibiotics.

A breast abscess, which is even rarer, is a collection of pus in the breast. An abscess may develop if a breast infection is not treated. An abscess is usually drained surgically and may be treated with antibiotics.

Breast Cancer

Among women, breast cancer is the second most common cancer and the second most common cause of cancer deaths.

Among women, breast cancer is the second most common cancer and the second most common cause of cancer deaths.

Typically, the first symptom is a painless lump, usually noticed by the woman.

Typically, the first symptom is a painless lump, usually noticed by the woman.

Monthly self-examination, yearly breast examination by a doctor, and a yearly mammogram for women who are over 50 or at increased risk are recommended.

Monthly self-examination, yearly breast examination by a doctor, and a yearly mammogram for women who are over 50 or at increased risk are recommended.

If a solid lump is detected, a few cells are removed through a needle or the entire lump is surgically removed and examined (biopsied).

If a solid lump is detected, a few cells are removed through a needle or the entire lump is surgically removed and examined (biopsied).

Breast cancer almost always requires surgery, sometimes with radiation therapy, chemotherapy, other drugs, or a combination.

Breast cancer almost always requires surgery, sometimes with radiation therapy, chemotherapy, other drugs, or a combination.

Outcome is hard to predict and depends partly on the characteristics and spread of the cancer.

Outcome is hard to predict and depends partly on the characteristics and spread of the cancer.

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer among women after skin cancer and, of cancers, is the second most common cause of death among women after lung cancer. In 2006, breast cancer was diagnosed in about 213,000 women in the United States. About one fifth of them will die of it.

Many women fear breast cancer, partly because it is common. However, some of the fear about breast cancer is based on misunderstanding. For example, the statement, “One of every eight women will get breast cancer,” is misleading. That figure is an estimate based on women from birth to age 95. It means that theoretically, one of eight women who live to age 95 or older will develop breast cancer. However, a 40-year-old woman has only a 1 in 1,200 chance of developing breast cancer during the next year and about a 1 in 120 chance of developing it during the next decade. But as she ages, her risk increases.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Fewer than 1% of women have the genes for breast cancer.

Several factors affect the risk of developing breast cancer. Thus, for some women, the risk is much higher or lower than average. Most factors that increase risk, such as age, cannot be modified. However, regular exercise, particularly during adolescence and young adulthood, and possibly weight control may reduce the risk of developing breast cancer. Regularly drinking alcoholic beverages may increase the risk.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS OF DEVELOPING OR DYING OF BREAST CANCER?

Far more important than trying to modify risk factors is being vigilant about detecting breast cancer so that it can be diagnosed and treated early, when it is more likely to be cured. Early detection is more likely when women have mammograms (see page 1554) and do breast self-examinations regularly (see art on page 1552).

Types

Breast cancer is usually classified by the extent of its spread and by the kind of tissue in which the cancer starts.

Carcinoma in situ means cancer in place. It is the earliest stage of breast cancer. Carcinoma in situ may be large and may even affect a substantial area of the breast, but it has not invaded the surrounding tissues or spread to other parts of the body. More than 15% of all breast cancers diagnosed in the United States are carcinoma in situ. It is usually detected during mammography.

Invasive cancer is further classified as follows.

Localized: The cancer has invaded surrounding tissues but is confined to the breast.

Localized: The cancer has invaded surrounding tissues but is confined to the breast.

Regional: The cancer has invaded tissues near the breasts, such as the chest wall or lymph nodes.

Regional: The cancer has invaded tissues near the breasts, such as the chest wall or lymph nodes.

Distant (metastatic): The cancer has spread from the breast to other parts of the body. Cancer tends to move into the lymphatic vessels in the breast. Most lymphatic vessels in the breast drain into lymph nodes in the armpit (axillary lymph nodes). One function of lymph nodes is to filter out and destroy abnormal or foreign cells, such as cancer cells. If cancer cells get past these lymph nodes, the cancer can spread anywhere in the body. Breast cancer can also spread through the bloodstream to other parts of the body. Breast cancer tends to spread to bones and the brain but can spread to any area, including the lungs, liver, skin, and scalp. Breast cancer can appear in these areas years or even decades after it is first diagnosed and treated. If the cancer has spread to one area, it probably has spread to other areas, even if it cannot be detected right away.

Distant (metastatic): The cancer has spread from the breast to other parts of the body. Cancer tends to move into the lymphatic vessels in the breast. Most lymphatic vessels in the breast drain into lymph nodes in the armpit (axillary lymph nodes). One function of lymph nodes is to filter out and destroy abnormal or foreign cells, such as cancer cells. If cancer cells get past these lymph nodes, the cancer can spread anywhere in the body. Breast cancer can also spread through the bloodstream to other parts of the body. Breast cancer tends to spread to bones and the brain but can spread to any area, including the lungs, liver, skin, and scalp. Breast cancer can appear in these areas years or even decades after it is first diagnosed and treated. If the cancer has spread to one area, it probably has spread to other areas, even if it cannot be detected right away.

Breast cancer that starts in the milk ducts is called ductal carcinoma. About 90% of all breast cancers are this type. Breast cancer that starts in the milk-producing glands (lobules) is called lobular carcinoma. Breast cancer that starts in fatty or connective tissue, a rare type, is called sarcoma.

Ductal carcinoma in situ is confined to the milk ducts of the breast. It does not invade surrounding breast tissue, but it can spread along the ducts and gradually affect a substantial area of the breast. This type accounts for 20 to 30% of breast cancers. It is detected only during mammography. This type may become invasive.

Lobular carcinoma in situ develops within the milk-producing glands of the breast. It often occurs in several areas of both breasts. Women with this type have a 1 to 2% chance each year of developing invasive breast cancer in the affected or the other breast. This type accounts for 1 to 2% of breast cancers. Usually, lobular carcinoma in situ cannot be seen on a mammogram and is detected only by biopsy.

Invasive ductal carcinoma begins in the milk ducts but breaks through the wall of the ducts, invading the surrounding breast tissue. It can also spread to other parts of the body. It accounts for 65 to 80% of breast cancers.

Risk Factors for Breast Cancer

AGE

Increasing age is an important risk factor. About 60% of breast cancers occur in women older than 60. Risk is greatest after age 75.

PREVIOUS BREAST CANCER

At highest risk are women who have had breast cancer. After the diseased breast is removed, the risk of developing cancer in the remaining breast is about 0.5 to 1.0% each year.

FAMILY HISTORY OF BREAST CANCER

Breast cancer in a first-degree relative (mother, sister, or daughter) increases a woman’s risk by 2 to 3 times, but breast cancer in more distant relatives (grandmother, aunt, or cousin) increases the risk only slightly. Breast cancer in two or more first-degree relatives increases a woman’s risk by 5 to 6 times.

BREAST CANCER GENE

Two separate genes for breast cancer (BRCA1 and BRCA2) have been identified in two separate small groups of women. Fewer than 1% of women have these genes. They are most common among Ashkenazi Jews. If a woman has one of these genes, her chances of developing breast cancer are very high, possibly as high as 50 to 85% by age 80. However, if such a woman develops breast cancer, her chances of dying of breast cancer are not necessarily greater than those of any other woman with breast cancer. Women likely to have one of these genes are those who have several close, usually first-degree relatives who have had breast cancer. For this reason, routine screening for these genes does not appear necessary, except in women who have such a family history.

The risk of ovarian cancer is increased in families with both breast cancer genes. The risk of breast cancer in men is increased in families with the BRCA2 gene.

Women with one of these genes may need to undergo more frequent testing for breast cancer. Or they may need to try to prevent cancer from developing by taking tamoxifen or raloxifene (which is similar to tamoxifen) or sometimes by even having a double mastectomy.

FIBROCYSTIC CHANGES

Having only certain types of fibrocystic changes seems to increase risk. These changes include those that require a biopsy to rule out breast cancer or those that make the breasts appear dense on a mammogram. For women with such changes, the risk is increased only slightly unless abnormal tissue structure (atypical hyperplasia) is detected during a biopsy or the women have a family history of breast cancer.

AGE AT FIRST MENSTRUAL PERIOD, AT FIRST PREGNANCY, AND AT MENOPAUSE

The earlier menstruation begins, the greater the risk of developing breast cancer. The risk is 1.2 to 1.4 times higher for women who first menstruated before age 12 than for those who first menstruated after age 14.

The later the first pregnancy occurs and the later menopause occurs, the higher the risk. Never having had a baby doubles the risk of developing breast cancer during a woman’s lifetime.

These factors probably increase risk because they involve longer exposure to estrogen, which stimulates the growth of certain cancers. (Pregnancy, although it results in high estrogen levels, may reduce the risk of breast cancer.)

PROLONGED USE OF ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES OR ESTROGEN THERAPY

Taking oral contraceptives increases the risk of later developing breast cancer, but only very slightly. Also, the risk is increased mainly for women who started taking them at a young age (such as during their teens) and who have taken them for many years. After women stop taking contraceptives, the risk gradually decreases over the next 10 years to that for other women of the same age.

After menopause, taking combination hormone therapy (estrogen with a progestin) for a few years or more increases the risk of breast cancer.

OBESITY AFTER MENOPAUSE

Risk is somewhat higher for women who are obese after menopause. However, there is no proof that a high-fat diet contributes to the development of breast cancer or that changing the diet can decrease risk. Some studies suggest that obese women who are still menstruating are less likely to develop breast cancer.

RADIATION EXPOSURE

Radiation exposure (such as radiation therapy for cancer or significant exposure to x-rays) before age 30 increases risk.

Invasive lobular carcinoma begins in the milk-producing glands of the breast but invades surrounding breast tissue and spreads to other parts of the body. It is more likely than other types of breast cancer to occur in both breasts. It accounts for 10 to 15% of breast cancers.

Inflammatory breast cancer refers to the symptoms of the cancer rather than the affected tissue. This type is fast growing and often fatal. Cancer cells block the lymphatic vessels in the skin of the breast, causing the breast to appear inflamed: swollen, red, and warm. Usually, inflammatory breast cancer spreads to the lymph nodes in the armpit. The lymph nodes can be felt as hard lumps. However, often no lump may be felt in the breast itself because this cancer is dispersed throughout the breast. Inflammatory breast cancer accounts for about 1% of breast cancers.

How to Do a Breast Self-Examination

1. While standing in front of a mirror, look at the breasts. The breasts normally differ slightly in size. Look for changes in the size difference between the breasts and changes in the nipple, such as turning inward (an inverted nipple) or a discharge. Look for puckering or dimpling.

2. Watching closely in the mirror, clasp the hands behind the head and press them against the head. This position helps make subtle changes caused by cancer more noticeable. Look for changes in the shape and contour of the breasts, especially in the lower part of the breasts.

3. Place the hands firmly on the hips and bend slightly toward the mirror, pressing the shoulders and elbows forward. Again, look for changes in shape and contour.

Many women do the next part of the examination in the shower because the hand moves easily over wet, slippery skin.

4. Raise the left arm. Using three or four fingers of the right hand, probe the left breast thoroughly with the flat part of the fingers. Moving the fingers in small circles around the breast, begin at the nipple and gradually move outward. Press gently but firmly, feeling for any unusual lump or mass under the skin. Be sure to check the whole breast. Also, carefully probe the armpit and the area between the breast and armpit for lumps.

5. Squeeze the left nipple gently and look for a discharge. (See a doctor if a discharge appears at any time of the month, regardless of whether it happens during breast self-examination.)

Repeat steps 4 and 5 for the right breast, raising the right arm and using the left hand.

6. Lie flat on the back with a pillow or folded towel under the left shoulder and with the left arm overhead. This position flattens the breast and makes it easier to examine. Examine the breast as in steps 4 and 5. Repeat for the right breast.

A woman should repeat this procedure at the same time each month. For menstruating women, 2 or 3 days after their period ends is a good time because the breasts are less likely to be tender and swollen. Postmenopausal women may choose any day of the month that is easy to remember, such as the first.

Adapted from a publication of the National Cancer Institute.

Paget’s disease of the nipple (see page 1337) is a ductal breast cancer. The first symptom is a crusty or scaly nipple sore or a discharge from the nipple. Slightly more than half of the women who have this cancer also have a lump in the breast that can be felt. Paget’s disease may be in situ or invasive. Because this disease usually causes little discomfort, women may ignore it for a year or more before seeing a doctor. The prognosis depends on how invasive and how large the cancer is as well as whether it has spread to the lymph nodes.

Rare types of invasive ductal breast cancers include medullary carcinoma, tubular carcinoma, and mucinous (colloid) carcinoma. Mucinous carcinoma tends to develop in older women and to be slow growing. Women with these types of breast cancer have a much better prognosis than women with other types of invasive breast cancer.

Phyllodes breast tumors are relatively rare. About half are cancerous. They originate in breast tissue around milk ducts and milk-producing glands. The tumor spreads to other parts of the body in about 10 to 20% of women who have it.

Characteristics

All cells, including breast cancer cells, have molecules on their surfaces called receptors. A receptor has a specific structure that allows only particular substances to fit into it and thus affect the cell’s activity. Whether breast cancer cells have certain receptors affects how quickly the cancer spreads and how it should be treated.

Estrogen and progesterone receptors: Some breast cancer cells have receptors for estrogen. The resulting cancer, described as estrogen receptor—positive, grows or spreads when stimulated by estrogen. This type of cancer is more common among postmenopausal women than among younger women. Some breast cancer cells have receptors for progesterone. The resulting cancer, described as progesterone receptor—positive, is stimulated by progesterone. Breast cancers with estrogen receptors and possibly those with progesterone receptors grow more slowly than those that do not have these receptors, and the prognosis is better.

Estrogen and progesterone receptors: Some breast cancer cells have receptors for estrogen. The resulting cancer, described as estrogen receptor—positive, grows or spreads when stimulated by estrogen. This type of cancer is more common among postmenopausal women than among younger women. Some breast cancer cells have receptors for progesterone. The resulting cancer, described as progesterone receptor—positive, is stimulated by progesterone. Breast cancers with estrogen receptors and possibly those with progesterone receptors grow more slowly than those that do not have these receptors, and the prognosis is better.

HER2 (HER2/neu) receptors: Normal breast cells have HER2 receptors, which help them grow. (HER stands for human epithelial growth factor receptor, which is involved in multiplication, survival, and differentiation of cells.) In about 20 to 30% of breast cancers, cancer cells have too many HER2 receptors. Such cancers tend to be very fast growing.

HER2 (HER2/neu) receptors: Normal breast cells have HER2 receptors, which help them grow. (HER stands for human epithelial growth factor receptor, which is involved in multiplication, survival, and differentiation of cells.) In about 20 to 30% of breast cancers, cancer cells have too many HER2 receptors. Such cancers tend to be very fast growing.

Symptoms

At first, breast cancer causes no symptoms. Most commonly, the first symptom is a lump, which usually feels distinctly different from the surrounding breast tissue. In more than 80% of breast cancer cases, women discover the lump themselves. Usually, scattered lumpy changes in the breast, especially the upper outer region, are not cancerous and indicate fibrocystic changes. A firm, distinctive thickening that appears in one breast but not the other may indicate cancer.

In the early stages, the lump may move freely beneath the skin when it is pushed with the fingers.

In more advanced stages, the lump usually adheres to the chest wall or the skin over it. In these cases, the lump cannot be moved at all or it cannot be moved separately from the skin over it. Women can detect whether they have a cancer that even slightly adheres to the chest wall or skin by lifting their arms over their head while standing in front of a mirror. If a breast contains cancer that adheres to the chest wall or skin, this maneuver may make the skin pucker or one breast appear different from the other.

In very advanced cancer, swollen bumps or festering sores may develop on the skin. Sometimes the skin over the lump is dimpled and leathery and looks like the skin of an orange (peau d’orange) except in color.

The lump may be painful, but pain is an unreliable sign. Pain without a lump is rarely due to breast cancer.

Lymph nodes, particularly those in the armpit on the affected side, may feel like hard small lumps. The lymph nodes may be stuck together or adhere to the skin or chest wall. They are usually painless but may be slightly tender.

In inflammatory breast cancer, the breast is warm, red, and swollen, as if infected (but it is not). The skin of the breast may become dimpled and leathery, like the skin of an orange, or may have ridges. The nipple may turn inward (invert). A discharge from the nipple is common. Often, no lump can be felt in the breast.

Screening

Because breast cancer rarely causes symptoms in its early stages and because early treatment is more likely to be successful, screening is important. Screening is the hunt for a disorder before any symptoms occur.

Routine self-examination enables women to detect lumps at an early stage. However, self-examination alone does not reduce the death rate from breast cancer, and it does not detect as many early cancers as routine screening with mammography. Women who do not detect any lumps should continue to see their doctor for breast examinations and to have mammograms as recommended. When tumors are detected by self-examination, the prognosis is usually better, and breast-conserving surgery can usually be done rather than mastectomy.

A breast examination is a routine part of a physical examination. A doctor inspects the breasts for irregularities, dimpling, tightened skin, lumps, and a discharge. The doctor feels (palpates) each breast with a flat hand and checks for enlarged lymph nodes in the armpit—the area most breast cancers invade first—and above the collarbone. Normal lymph nodes cannot be felt through the skin, so those that can be felt are considered enlarged. However, noncancerous conditions can also cause lymph nodes to enlarge. Lymph nodes that can be felt are checked to see if they adhere to the skin or chest wall and if they are matted together.

Mammography: For this test, x-rays are used to check for abnormal areas in the breast. A technician positions the woman’s breast on top of an x-ray plate. An adjustable plastic cover is lowered on top of the breast, firmly compressing the breast. Thus, the breast is flattened so that the maximum amount of tissue can be imaged and examined. X-rays are aimed downward through the breast, producing an image on the x-ray plate. Two x-rays are taken of each breast in this position. Then plates may be placed vertically on either side of the breast, and x-rays are aimed from the side. This position produces a side view of the breast.

Mammography is one of the best ways to detect breast cancer early. Mammography is designed to be sensitive enough to detect the possibility of cancer at an early stage, sometimes years before it can be felt. Because mammography is so sensitive, it may indicate cancer when none is present—a false-positive result. About 90% of abnormalities detected during screening (that is, in women with no symptoms or lumps) are not cancer. Typically, when the result is positive, more specific follow-up procedures, usually a breast biopsy, are scheduled to confirm the result. Mammography may miss up to 15% of breast cancers.

Mammography: Screening for Breast Cancer

Having a mammogram every 1 to 2 years can reduce the rate of death due to breast cancer by 25 to 35% among women aged 50 and older. As yet, no study has shown that regularly having mammograms can reduce the death rate among women younger than 50. However, evidence may be harder to obtain because breast cancer is not common among younger women. Many experts recommend that women aged 40 to 49 have mammograms every 1 to 2 years. All experts recommend yearly mammograms for women aged 50 and older.

The dose of radiation used is very low and is considered safe. Mammography may cause some discomfort, but the discomfort lasts only a few seconds. Mammography should be scheduled at a time during the menstrual period when the breasts are less likely to be tender. Deodorants should not be used on the day of the procedure because they can interfere with the image obtained. The entire procedure takes about 15 minutes.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Only about 10% of the abnormalities detected during routine screening with mammography turn out to be cancer.

Diagnosis

When a lump or another abnormality is detected in the breast during a physical examination or by a screening procedure, other procedures are necessary. Mammography is done first if it was not the way the abnormality was detected.

Ultrasonography is sometimes used to help distinguish between a fluid-filled sac (cyst) and a solid lump. This distinction is important because cysts are usually not cancerous. Cysts may be monitored (with no treatment) or drained with a small needle and syringe. Sometimes the fluid from the cyst is examined to check for cancer cells. Rarely, when cancer is suspected, cysts are removed.

If the abnormality is a solid lump, which is more likely to be cancerous, a mammogram followed by a biopsy is done. Often, an aspiration biopsy is used: Some cells are removed from the lump through a needle attached to a syringe. If this procedure detects cancer, the diagnosis is confirmed. If no cancer is detected, removal of an additional piece of tissue (incisional biopsy) or of the entire lump (excisional biopsy) is necessary to be sure that the aspiration biopsy did not miss the cancer. Most women do not need to be hospitalized for these procedures. Usually, only a local anesthetic is needed.

If Paget’s disease of the nipple is suspected, a biopsy of nipple tissue is usually done. Sometimes this cancer can be diagnosed by examining a sample of the nipple discharge under a microscope.

A pathologist examines the biopsy samples under the microscope to determine whether cancer cells are present. Generally, a biopsy confirms cancer in only a few women with an abnormality detected during mammography. If cancer cells are detected, the sample is analyzed to determine the characteristics of the cancer cells, such as

Whether the cancer cells have estrogen or progesterone receptors

Whether the cancer cells have estrogen or progesterone receptors

How many HER2 receptors are present

How many HER2 receptors are present

How quickly the cancer cells are dividing

How quickly the cancer cells are dividing

This information helps doctors estimate how rapidly the cancer may spread and which treatments are more likely to be effective.

A chest x-ray is taken and blood tests, including a complete blood cell count and liver function tests, are done to determine whether the cancer has spread. If the tumor is large, if the lymph nodes are enlarged, or if women have bone pain, imaging of bones throughout the body (a bone scan) may be done. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen is done if liver function is abnormal, if the liver is enlarged, or if the cancer has spread within the breast.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often done to evaluate breast cancer after it is diagnosed because MRI can accurately determine how large the tumor is, whether the chest wall is involved, and how many tumors are present.

Staging

When cancer is diagnosed, a stage is assigned to it, based on how advanced it is. The stage helps doctors determine the most appropriate treatment and the prognosis. Stages of breast cancer may be described generally as in situ (not invasive) or invasive. Stages may be described in detail and designated by a number (0 through IV).

Prevention

Taking drugs that decrease the risk of breast cancer (chemoprevention) is recommended for the following women:

Those over age 60

Those over age 60

Those who are over age 35 and have had a previous lobular carcinoma in situ

Those who are over age 35 and have had a previous lobular carcinoma in situ

Those who have BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations

Those who have BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations

Those who have a high risk of developing breast cancer based on the woman’s current age, age at menarche, age at first live childbirth, number of first-degree relatives with breast cancer, and results of prior breast biopsies

Those who have a high risk of developing breast cancer based on the woman’s current age, age at menarche, age at first live childbirth, number of first-degree relatives with breast cancer, and results of prior breast biopsies

STAGES OF BREAST CANCER

| STAGE | DESCRIPTION |

| In situ carcinoma | |

| The tumor is confined, usually to a milk duct or milk-producing gland, and has not invaded surrounding breast tissue. | |

| Localized and regional invasive cancer | |

| I | The tumor is less than ¾ inch (2 centimeters) in diameter and has not spread beyond the breast. |

| IIA | The tumor is ¾ inch or less in diameter, and it has spread to one to three lymph nodes in the armpit, microscopic amounts have spread to lymph nodes near the breastbone on the same side as the tumor, or both. or The tumor is larger than ¾ inch but smaller than 2 inches (5 centimeters) in diameter but has not spread beyond the breast. |

| IIB | The tumor is larger than ¾ inch but smaller than 2 inches in diameter, and it has spread to one to three lymph nodes in the armpit, microscopic amounts have spread to lymph nodes near the breastbone on the same side as the tumor, or both. or The tumor is larger than 2 inches in diameter but has not spread beyond the breast. |

| IIIA | The tumor is 2 inches or less in diameter and has spread to four to nine lymph nodes in the armpit or has enlarged at least one lymph node near the breastbone on the same side as the tumor. or The tumor is larger than 2 inches in diameter and has spread to up to nine lymph nodes in the armpit or to lymph nodes near the breastbone. |

| IIIB | The tumor has spread to the chest wall or skin or has caused breast inflammation (inflammatory breast cancer). |

| IIIC | The tumor can be any size plus at least one of the following:

|

| Metastatic cancer | |

| IV | The tumor, regardless of size, has spread to distant organs or tissues, such as the lungs or bones, or to lymph nodes distant from the breast. |

These drugs include tamoxifen and raloxifene. Women should ask their doctor about possible side effects before beginning chemoprevention. Risks of tamoxifen include cancer of the uterus (endometrial cancer), blood clots in the legs or lungs, and cataracts. These risks are higher for older women. Raloxifene appears to be about as effective as tamoxifen in postmenopausal women and to have a lower risk of blood clots and cataracts. Both drugs may also increase bone density and thus benefit women who have osteoporosis. For postmenopausal women, raloxifene is an alternative to tamoxifen.

TREATING CANCER BASED ON TYPE

| TYPE | POSSIBLE TREATMENTS |

| Ductal carcinoma in situ | Mastectomy Wide excision with or without radiation therapy |

| Lobular carcinoma in situ | Observation plus regular examinations and mammograms Tamoxifen or, for some postmenopausal women, raloxifene to reduce the risk of invasive cancer Bilateral mastectomy (rarely) to prevent invasive cancers |

| Stages I and II (early-stage) cancer | Chemotherapy before surgery if the tumor is larger than 2 inches (5 centimeters) Breast-conserving surgery to remove the tumor and some surrounding tissue, usually followed by radiation therapy Sometimes mastectomy with breast reconstruction After surgery, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, trastuzumab, or a combination, except in some postmenopausal women with tumors smaller than 0.4 inches (1 centimeter) |

| Stage III (locally advanced) cancer (including inflammatory breast cancer) | Chemotherapy or sometimes hormonal therapy before surgery to reduce the tumor’s size Breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy if the tumor is small enough to be completely removed Mastectomy for inflammatory breast cancer Usually, radiation therapy after surgery Sometimes chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, or both after surgery |

| Stage IV (metastatic) cancer | If cancer causes symptoms and occurs in several sites, hormone therapy, ovarian ablation therapy,* or chemotherapy

For metastases to bone, IV bisphosphonates (such as zoledronate or pamidronate) to reduce bone pain and bone loss |

| Paget’s disease of the nipple | Usually, the same as for other types of breast cancer Occasionally, local excision only |

| Breast cancer that recurs in the breast or nearby structures | Radical or modified radical mastectomy sometimes preceded by chemotherapy or hormone therapy |

| Phyllodes tumors if they are cancerous | Wide excision Mastectomy if the tumor is large |

| *Ovarian ablation therapy involves removing the ovaries or using drugs to suppress estrogen production by the ovaries. | |

Treatment

Usually, treatment begins after the woman’s condition has been thoroughly evaluated, about a week or more after the biopsy. Treatment options depend on the stage and type of breast cancer. However, treatment is complex because the different types of breast cancer differ greatly in growth rate, tendency to spread (metastasize), and response to treatment. Also, much is still unknown about breast cancer. Consequently, doctors may have different opinions about the most appropriate treatment for a particular woman.

Surgery for Breast Cancer

Surgery for breast cancer consists of two main options.

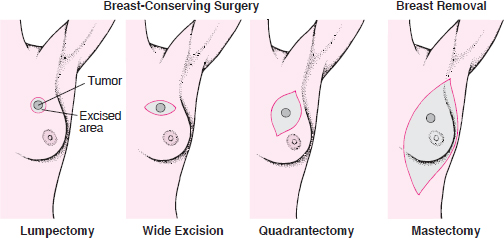

In breast-conserving surgery, only the tumor and an area of normal tissue surrounding it are removed. Breast-conserving surgery includes the following:

Lumpectomy: A small amount of surrounding normal tissue is removed.

Lumpectomy: A small amount of surrounding normal tissue is removed.

Wide excision (partial mastectomy): A somewhat larger amount of the surrounding normal tissue is removed.

Wide excision (partial mastectomy): A somewhat larger amount of the surrounding normal tissue is removed.

Quadrantectomy: One fourth of the breast is removed.

Quadrantectomy: One fourth of the breast is removed.

In mastectomy, all breast tissue is removed.

The preferences of a woman and her doctor affect treatment decisions. Women with breast cancer should ask for a clear explanation of what is known about the cancer and what is still unknown, as well as a complete description of treatment options. Then, they can consider the advantages and disadvantages of the different treatments and accept or reject the options offered. Losing some or all of a breast can be emotionally traumatic. Women must consider how they feel about this treatment, which can deeply affect their sense of wholeness and sexuality.

Doctors may ask women with breast cancer to participate in research studies investigating a new treatment. New treatments aim to improve the chances of survival or quality of life. All women who participate in a research study are treated because a new treatment is compared with other effective treatments. Women should ask their doctor to explain the risks and possible benefits of participation, so that they can make a well-informed decision.

Treatment usually involves surgery and may include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or hormone-blocking drugs. Often, a combination of these treatments is used.

Surgery: The cancerous tumor and varying amounts of the surrounding tissue are removed. There are two main options for removing the tumor: breast-conserving surgery and removal of the breast (mastectomy). For women with invasive cancer (stage I or higher), mastectomy is no more effective than breast-conserving surgery plus radiation therapy as long as the entire tumor can be removed during breast-conserving surgery. Before surgery, chemotherapy may be used to shrink the tumor before removing it. This approach sometimes enables some women to have breast-conserving surgery rather than mastectomy.

Breast-conserving surgery leaves as much of the breast intact as possible. There are several types:

Lumpectomy is removal of the tumor with a small amount of surrounding normal tissue.

Lumpectomy is removal of the tumor with a small amount of surrounding normal tissue.

Wide excision or partial mastectomy is removal of the tumor and a somewhat larger amount of surrounding normal tissue.

Wide excision or partial mastectomy is removal of the tumor and a somewhat larger amount of surrounding normal tissue.

Quadrantectomy is removal of one fourth of the breast.

Quadrantectomy is removal of one fourth of the breast.

Removing the tumor with some normal tissue provides the best chance of preventing cancer from recurring within the breast. Breast-conserving surgery is usually combined with radiation therapy.

The major advantage of breast-conserving surgery is cosmetic: This surgery may help preserve body image. Thus, when the tumor is large in relation to the breast, this type of surgery is less likely to be useful. In such cases, removing the tumor plus some surrounding normal tissue means removing most of the breast. Breast-conserving surgery is usually more appropriate when tumors are small. In about 15% of women who have breast-conserving surgery, the amount of tissue removed is so small that little difference can be seen between the treated and untreated breasts. However, in most women, the treated breast shrinks somewhat and may change in contour.

Mastectomy is the other main surgical option. There are several types:

Simple mastectomy consists of removing all breast tissue but leaving the muscle under the breast and enough skin to cover the wound. Reconstruction of the breast is much easier if these tissues are left. A simple mastectomy, rather than breast-conserving surgery, is usually done when there is a substantial amount of cancer in the milk ducts.

Simple mastectomy consists of removing all breast tissue but leaving the muscle under the breast and enough skin to cover the wound. Reconstruction of the breast is much easier if these tissues are left. A simple mastectomy, rather than breast-conserving surgery, is usually done when there is a substantial amount of cancer in the milk ducts.

Modified radical mastectomy consists of removing all breast tissue and some lymph nodes in the armpit but leaving the muscle under the breast. This procedure is usually done instead of a radical mastectomy.

Modified radical mastectomy consists of removing all breast tissue and some lymph nodes in the armpit but leaving the muscle under the breast. This procedure is usually done instead of a radical mastectomy.  Radical mastectomy consists of removing all breast tissue plus the lymph nodes in the armpit and the muscle under the breast. This procedure is rarely done now.

Radical mastectomy consists of removing all breast tissue plus the lymph nodes in the armpit and the muscle under the breast. This procedure is rarely done now.

Lymph node surgery (lymph node dissection) is also done if the cancer is or is suspected to be invasive. Nearby lymph nodes (usually about 10 to 20) are removed and examined to determine whether the cancer has spread to them. If cancer cells are detected in the lymph nodes, the cancer is more likely to have spread to other parts of the body. In such cases, additional treatment is needed. Removal of lymph nodes often causes problems because it affects the drainage of fluids in tissues. As a result, fluids may accumulate, causing persistent swelling (lymphedema) of the arm or hand. Arm and shoulder movement may be limited. Lymphedema may be treated by specially trained therapists. Women are taught how to massage the area, which may help the accumulated fluid drain, and how to apply a bandage, which helps keep fluid from reaccumulating. The affected arm should be used as normally as possible, except that the unaffected arm should be used for heavy lifting. Women should exercise the affected arm daily as instructed and bandage it overnight indefinitely. Other problems include temporary or persistent numbness, a persistent burning sensation, and infection.

What Is a Sentinel Lymph Node?

A network of lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes drain fluid from the tissue in the breast. The lymph nodes are designed to trap foreign or abnormal cells (such as bacteria or cancer cells) that may be contained in this fluid. Sometimes cancer cells pass through the nodes into the lymphatic vessels and spread to other parts of the body. Usually, the fluid from breast tissue drains through a single nearby lymph node first, but it may drain through more than one. Such lymph nodes are called sentinel lymph nodes.

Doctors can identify the sentinel lymph node by injecting blue dye or a radioactive substance into the fluid surrounding the breast cells. Doctors use a scanner to observe the dye or detect the radioactive substance when it reaches the first lymph nodes. The sentinel lymph node is then removed and examined to determine whether it contains cancer cells. If it does, other nearby lymph nodes are removed. If the sentinel lymph node does not contain cancer cells, the other lymph nodes are not removed. However, this biopsy is not completely reliable. In about 2 to 3% of women, cancer has spread to other lymph nodes when the sentinel lymph node is clear.

A sentinel lymph node biopsy is an alternative that may minimize or avoid the problems of lymph node surgery. This procedure involves locating and removing the first lymph node (or nodes) that the tumor drains into. If this node contains cancer cells, the other lymph nodes are removed. If it does not, the other lymph nodes are not removed. Whether this procedure is as effective as standard lymph node surgery is being studied.

Breast reconstruction surgery may be done at the same time as a mastectomy or later. A silicone or saline implant or tissue taken from other parts of the woman’s body may be used. The safety of silicone implants, which sometimes leak, has been questioned. However, there is almost no evidence suggesting that silicone leakage has serious effects.

Radiation Therapy: This treatment is used to kill cancer cells at and near the site from which the tumor was removed, including nearby lymph nodes. Radiation therapy after mastectomy reduces the risk of cancer recurring near the site and in nearby lymph nodes. It may improve the chances of survival of women who have large tumors or cancer that has spread to several nearby lymph nodes.

Side effects include swelling in the breast, reddening and blistering of the skin in the treated area, and fatigue. These effects usually disappear within several months, up to about 12 months. Fewer than 5% of women treated with radiation therapy have rib fractures that cause minor discomfort. In about 1% of women, the lungs become mildly inflamed 6 to 18 months after radiation therapy is completed. Inflammation causes a dry cough and shortness of breath during physical activity that last for up to about 6 weeks.

To improve radiation therapy, doctors are studying several new procedures. Many of these aim to target radiation to the cancer more precisely and spare the rest of the breast from the effects of radiation. In one procedure, tiny radioactive seeds are inserted through a catheter to the tumor site. Radiation therapy can be completed in only 5 days. It is not clear whether these new procedures are as effective as traditional radiation therapy.

Drugs: Chemotherapy and hormone-blocking drugs can suppress the growth of cancer cells throughout the body. Chemotherapy and sometimes hormone-blocking drugs are used in addition to surgery and radiation therapy if cancer cells are detected in the lymph nodes and often if they are not. These drugs are often started soon after breast surgery and are continued for several months. Some, such as tamoxifen, may be continued for up to 5 years. These drugs delay the recurrence of cancer and prolong survival in most women. Analyzing the genetic material of the cancer (predictive genomic testing) may help predict which cancers are susceptible to chemotherapy or hormone-blocking drugs.

Chemotherapy is used to kill rapidly multiplying cells or slow their multiplication. Chemotherapy alone cannot cure breast cancer. It must be used with surgery or radiation therapy. Chemotherapy drugs are usually given intravenously in cycles. Sometimes they are given by mouth. Typically, a day of treatment is followed by several weeks of recovery. Using several chemotherapy drugs together is more effective than using a single drug. The choice of drugs depends partly on whether cancer cells are detected in nearby lymph nodes. Commonly used drugs include cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, epirubicin, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, and paclitaxel (see table on page 1090). Side effects (such as vomiting, nausea, hair loss, and fatigue) vary depending on which drugs are used. Chemotherapy can cause infertility and early menopause by destroying the eggs in the ovaries. Chemotherapy may also suppress the production of blood cells by the bone marrow. So drugs, such as filgrastim or peg-filgrastim, may by used to stimulate the bone marrow.

Hormone-blocking drugs interfere with the actions of estrogen or progesterone, which stimulate the growth of cancer cells that have estrogen or progesterone receptors. These drugs may be used when cancer cells have these receptors.

Tamoxifen: Tamoxifen, given by mouth, is a selective estrogen-receptor modulator. It binds with estrogen receptors and inhibits growth of breast tissue. In women who have estrogen receptor—positive cancer, tamoxifen increases the likelihood of survival during the first 10 years after diagnosis by about 20 to 25%. Tamoxifen, which is related to estrogen, has some of the benefits and risks of estrogen therapy taken after menopause (see page 1517). For example, it may decrease the risk of osteoporosis and fractures. It increases the risk of blood clots in the legs and lungs. It also substantially increases the risk of developing endometrial cancer. Thus, if women taking tamoxifen have spotting or bleeding from the vagina, they should see their doctor. However, the improvement in survival after breast cancer far outweighs the risk of endometrial cancer. Tamoxifen, unlike estrogen therapy, may worsen the vaginal dryness or hot flashes that occur after menopause. Tamoxifen is usually taken for 5 years.

Tamoxifen: Tamoxifen, given by mouth, is a selective estrogen-receptor modulator. It binds with estrogen receptors and inhibits growth of breast tissue. In women who have estrogen receptor—positive cancer, tamoxifen increases the likelihood of survival during the first 10 years after diagnosis by about 20 to 25%. Tamoxifen, which is related to estrogen, has some of the benefits and risks of estrogen therapy taken after menopause (see page 1517). For example, it may decrease the risk of osteoporosis and fractures. It increases the risk of blood clots in the legs and lungs. It also substantially increases the risk of developing endometrial cancer. Thus, if women taking tamoxifen have spotting or bleeding from the vagina, they should see their doctor. However, the improvement in survival after breast cancer far outweighs the risk of endometrial cancer. Tamoxifen, unlike estrogen therapy, may worsen the vaginal dryness or hot flashes that occur after menopause. Tamoxifen is usually taken for 5 years.

Aromatase inhibitors: These drugs (anastrozole, exemestane, and letrozole) inhibit aromatase (an enzyme that converts some hormones to estrogen) and thus may reduce the production of estrogen. In postmenopausal women, these drugs may be more effective than tamoxifen. These drugs may be given with tamoxifen or after tamoxifen has been used for 5 years. Aromatase inhibitors may increase the risk of osteoporosis.

Aromatase inhibitors: These drugs (anastrozole, exemestane, and letrozole) inhibit aromatase (an enzyme that converts some hormones to estrogen) and thus may reduce the production of estrogen. In postmenopausal women, these drugs may be more effective than tamoxifen. These drugs may be given with tamoxifen or after tamoxifen has been used for 5 years. Aromatase inhibitors may increase the risk of osteoporosis.

Rebuilding a Breast

After a general surgeon removes a breast tumor and the surrounding breast tissue (mastectomy), a plastic surgeon may reconstruct the breast. A silicone or saline implant may be used. Or in a more complex operation, tissue may be taken from other parts of the woman’s body, usually the abdomen. Reconstruction may be done at the same time as the mastectomy—a choice that involves being under anesthesia for a longer time—or later—a choice that involves being under anesthesia a second time.

In many women, a reconstructed breast looks more natural than one that has been treated with radiation therapy, especially if the tumor was large.

If a silicone or saline implant is used and enough skin was left to cover it, the sensation in the skin over the implant is relatively normal. However, neither type of implant feels like breast tissue to the touch. If skin from other parts of the body is used to cover the breast, much of the sensation is lost. However, tissue from other parts of the body feels more like breast tissue than does a silicone or saline implant.

Silicone occasionally leaks out of its sack. As a result, an implant can become hard, cause discomfort, and appear less attractive. Also, silicone sometimes enters the bloodstream. Some women are concerned about whether the leaking silicone causes cancer in other parts of the body or rare diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus). There is almost no evidence suggesting that silicone leakage has these serious effects, but because it might, the use of silicone implants has decreased, especially among women who have not had breast cancer.

Monoclonal antibodies are synthetic copies (or slightly modified versions) of natural substances that are part of the body’s immune system. These drugs enhance the immune system’s ability to fight cancer. Trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody, is used with chemotherapy to treat metastatic breast cancer only when the cancer cells have too many HER2 receptors. This drug binds with HER2 receptors and thus helps prevent cancer cells from multiplying. Trastuzumab is usually taken for a year. It can weaken the heart muscle.

Treatment of Noninvasive Cancer (Stage 0)

For ductal carcinoma in situ, treatment usually consists of a simple mastectomy or wide excision with or without radiation therapy.

For lobular carcinoma in situ, treatment is less clear-cut. For many women, the preferred treatment is close observation with no treatment. Observation consists of a physical examination every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and once a year thereafter plus mammography once a year. No treatment is usually needed. Although invasive breast cancer may develop (the risk is 1.3% per year or 26% for 20 years), the invasive cancers that develop are usually not fast growing and can usually be treated effectively. Furthermore, because invasive cancer is equally likely to develop in either breast, the only way to eliminate the risk of breast cancer for women with lobular carcinoma in situ is removal of both breasts (bilateral mastectomy). Some women, particularly those who are at high risk of developing invasive breast cancer, choose this option.

Alternatively, tamoxifen, a hormone-blocking drug, may be given for 5 years. It reduces but does not eliminate the risk of developing invasive cancer. Women with lobular carcinoma in situ are often given tamoxifen, but postmenopausal women may be given raloxifene.

Treatment of Localized or Regional Invasive Cancer (Stages I through III)

For cancers that have not spread beyond nearby lymph nodes, treatment almost always includes surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible. Nearby lymph nodes or the sentinel lymph node are sampled to help stage the cancer.

A simple mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery is commonly used to treat invasive cancer that has spread extensively within the milk ducts (invasive ductal carcinoma). Breast-conserving surgery is used only when the tumor is not too large because the entire tumor plus some of the surrounding normal tissue must be removed.

Whether radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or both are used after surgery depends on how large the tumor is and how many lymph nodes contain cancer cells. Breast-conserving surgery is usually followed by radiation therapy. Sometimes, when the tumor is too large for breast-conserving surgery, chemotherapy is given before surgery to reduce the size of the tumor. If chemotherapy reduces the size of the tumor enough, breast-conserving surgery may be possible. After surgery and radiation therapy, additional chemotherapy is usually given. If the cancer has estrogen receptors, women who are still menstruating are usually given tamoxifen, and postmenopausal women are given an aromatase inhibitor.

Treatment of Cancer That Has Spread (Stage IV)

Breast cancer that has spread beyond the lymph nodes is rarely cured, but most women who have it live at least 2 years, and a few live 10 to 20 years. Treatment extends life only slightly but may relieve symptoms and improve quality of life. However, some treatments have troublesome side effects. Thus, the decision of whether to be treated and, if so, which treatment to choose can be highly personal.

Most women are treated with chemotherapy or hormone-blocking drugs. However, chemotherapy, especially regimens that have uncomfortable side effects, are often postponed until symptoms (pain or other discomfort) develop or the cancer starts to worsen quickly. Pain is usually treated with analgesics. Other drugs may be given to relieve other symptoms. Chemotherapy or hormone-blocking drugs are given to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life rather than to prolong life. The most effective chemotherapy regimens for breast cancer that has spread include capecitabine, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel, doxorubicin, epirubicin, gemcitabine, paclitaxel, and vinorelbine.

Hormone-blocking drugs are preferred to chemotherapy in certain situations. For example, these drugs may be preferred when the cancer is estrogen receptor—positive, when cancer has not recurred for more than 2 years after diagnosis and initial treatment, or when cancer is not immediately life threatening. Different drugs are used in different situations:

Tamoxifen: For women who are still menstruating, tamoxifen is usually the first hormone-blocking drug used because it has few side effects.

Tamoxifen: For women who are still menstruating, tamoxifen is usually the first hormone-blocking drug used because it has few side effects.

Aromatase inhibitors: For postmenopausal women who have estrogen receptor—positive breast cancer, aromatase inhibitors (such as anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane) may be more effective as a first treatment than tamoxifen.

Aromatase inhibitors: For postmenopausal women who have estrogen receptor—positive breast cancer, aromatase inhibitors (such as anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane) may be more effective as a first treatment than tamoxifen.

Progestins: These drugs, such as medroxyprogesterone or megestrol, may be used instead of aromatase inhibitors and tamoxifen and have almost as few side effects.

Progestins: These drugs, such as medroxyprogesterone or megestrol, may be used instead of aromatase inhibitors and tamoxifen and have almost as few side effects.

Fulvestrant: This drug may be used when tamoxifen is no longer effective. It destroys the estrogen receptors in cancer cells. The most common side effect is stomach upset.

Fulvestrant: This drug may be used when tamoxifen is no longer effective. It destroys the estrogen receptors in cancer cells. The most common side effect is stomach upset.

Alternatively, for women who are still menstruating, surgery to remove the ovaries, radiation to destroy them, or drugs to inhibit their activity (such as buserelin, goserelin, or leuprolide) may be used to stop estrogen production.

For cancers that have too many HER2 receptors and that have spread throughout the body, trastuzumab can be used alone or with chemotherapy such as paclitaxel. Trastuzumab can also be used with hormone-blocking drugs to treat women who have estrogen receptor—positive breast cancer.

In some situations, radiation therapy may be used instead of or before drugs. For example, if only one area of cancer is detected and that area is in a bone, radiation to that bone might be the only treatment used. Radiation therapy is usually the most effective treatment for cancer that has spread to bone, sometimes keeping it in check for years. It is also often the most effective treatment for cancer that has spread to the brain.

Surgery may be done to remove single tumors in other parts of the body (such as the brain) because such surgery can relieve symptoms.

Bisphosphonates (used to treat osteoporosis), such as pamidronate or zoledronate, reduce bone pain and bone loss and may prevent or delay bone problems that can result when cancer spreads to bone.

Treatment of Specific Types of Breast Cancer

For inflammatory breast cancer, treatment usually consists of both chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Mastectomy is usually done.

For Paget’s disease of the nipple, treatment is usually similar to that of other types of breast cancer. It often involves simple mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery plus removal of the lymph nodes. Breast-conserving surgery is usually followed by radiation therapy. Less commonly, only the nipple with some surrounding normal tissue is removed.

For phyllodes tumors that are cancerous, treatment usually consists of wide excision. The tumor and a large amount of surrounding normal tissue are removed. If the tumor is large in relation to the breast, a simple mastectomy may be done. After surgical removal, about 20 to 35% of cancers recur near the same site.

Follow-up Care

After treatment is completed, follow-up physical examinations, including examination of the breasts, chest, neck, and armpits, are done every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months for 5 years from the date the cancer was diagnosed. Regular mammograms and breast self-examinations are also important. Women should promptly report certain symptoms to their doctor:

Any changes in their breasts

Any changes in their breasts

Pain

Pain

Loss of appetite or weight

Loss of appetite or weight

Changes in menstruation

Changes in menstruation

Bleeding from the vagina (if not associated with menstrual periods)

Bleeding from the vagina (if not associated with menstrual periods)

Blurred vision

Blurred vision

Any symptoms that seem unusual or that persist

Any symptoms that seem unusual or that persist

Diagnostic procedures, such as chest x-rays, blood tests, bone scans, and computed tomography (CT), are not needed unless symptoms suggest the cancer has recurred.

The effects of treatment for breast cancer cause many changes in a woman’s life. Support from family members and friends can help, as can support groups. Counseling may be helpful.

End-of-Life Issues

For women with metastatic breast cancer, quality of life may deteriorate, and the chances that further treatment will prolong life may be small. Staying comfortable may eventually become more important than trying to prolong life. Cancer pain can be adequately controlled with appropriate drugs (see page 61). So if women are having pain, they should ask their doctor for treatment to relieve it. Treatments can also relieve other troublesome symptoms, such as constipation, difficulty breathing, and nausea. Psychologic and spiritual counseling may also help.

Women with metastatic breast cancer should prepare advance directives indicating the type of care they desire in case they are no longer able to make such decisions (see page 69). Also, making or updating a will is important.