CHAPTER 246

Noncancerous Gynecologic Abnormalities

Noncancerous (benign) gynecologic growths include cysts, polyps, and myomas. Noncancerous growths can develop on the vulva or in the vagina, uterus, or ovaries. Occasionally, cysts or tumors in an ovary can cause the ovary to twist—a disorder called adnexal torsion. Rarely, certain growths become cancerous. Another abnormality is narrowing of the passageway through the lower part of the uterus (cervix) to the larger upper part (body)—a disorder called cervical stenosis.

Adnexal Torsion

Adnexal torsion is twisting of the ovary and sometimes the fallopian tube, cutting off the blood supply of these organs.

Twisting causes sudden, severe pain and often vomiting.

Twisting causes sudden, severe pain and often vomiting.

Doctors use an ultrasound device inserted into the vagina (transvaginal ultrasonography) to confirm the diagnosis.

Doctors use an ultrasound device inserted into the vagina (transvaginal ultrasonography) to confirm the diagnosis.

Surgery is done immediately to untwist the ovary and often to remove it.

Surgery is done immediately to untwist the ovary and often to remove it.

An ovary and sometimes the fallopian tube twist on the ligament-like tissues that support them. Twisting of an ovary (adnexal torsion) is uncommon but is more likely to occur in women of reproductive age. It usually occurs when there is a problem with an ovary. The following conditions make it more likely to occur:

Pregnancy

Pregnancy

Use of hormones to trigger ovulation (for infertility problems)

Use of hormones to trigger ovulation (for infertility problems)

Enlargement of the ovary, usually due to noncancerous (benign) tumors or cysts

Enlargement of the ovary, usually due to noncancerous (benign) tumors or cysts

Noncancerous tumors are more likely to cause twisting than cancerous ones.

Rarely, a normal ovary twists. Children are more likely to have this type of torsion.

Adnexal torsion usually occurs on only one side. Usually, only the ovary is involved, but occasionally, the fallopian tube also twists. Sometimes the blood supply to the ovary is cut off long enough to cause tissue in the ovary to die. Adnexal torsion can cause peritonitis—infection of the spaces in the abdomen (abdominal cavity) and the tissues lining it.

Symptoms

When an ovary twists, women have sudden, severe pain in the pelvic area. The pain is sometimes accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Before the sudden pain, women may have intermittent, crampy pain for days or occasionally even for weeks. This pain may occur because the ovary repeatedly twists, then untwists. The abdomen may feel tender.

Diagnosis

Doctors usually suspect the disorder based on symptoms and results of a physical examination. Ultrasonography using an ultrasound device inserted into the vagina (transvaginal ultrasonography) is done to confirm the diagnosis. This procedure can also usually determine whether blood flow to the ovary has been cut off.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

The ovary sometimes twists, causing sudden, severe pain.

Treatment

If ultrasonography supports the diagnosis, women are treated immediately. One of the following procedures is used:

Laparoscopy: Doctors may make a few small incisions in the abdomen. They then insert a flexible viewing tube (laparoscope) through the incision. Using instruments threaded through other incisions, they try to untwist the ovary and, if also twisted, the fallopian tube. Laparoscopy is done in a hospital and usually requires a general anesthetic, but it does not require an overnight stay.

Laparoscopy: Doctors may make a few small incisions in the abdomen. They then insert a flexible viewing tube (laparoscope) through the incision. Using instruments threaded through other incisions, they try to untwist the ovary and, if also twisted, the fallopian tube. Laparoscopy is done in a hospital and usually requires a general anesthetic, but it does not require an overnight stay.

Laparotomy: Doctors make a larger incision in the abdomen. A laparoscope is not used because doctors can directly view the affected organs. Because the incision is larger, it requires an overnight stay in the hospital.

Laparotomy: Doctors make a larger incision in the abdomen. A laparoscope is not used because doctors can directly view the affected organs. Because the incision is larger, it requires an overnight stay in the hospital.

If the blood supply was cut off and tissue died, removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries (salpingo-oophorectomy) is necessary. If an ovarian cyst is present, it is removed (called cystectomy). If an ovarian tumor is present, the entire ovary is removed (called oophorectomy).

Cervical Myomas

Cervical myomas are smooth, benign tumors in the cervix.

A myoma may bleed, become infected, interfere with urinating, or cause pain during sexual intercourse.

A myoma may bleed, become infected, interfere with urinating, or cause pain during sexual intercourse.

Doctors can see or feel most myomas during a pelvic examination.

Doctors can see or feel most myomas during a pelvic examination.

Myomas that cause symptoms can be removed surgically.

Myomas that cause symptoms can be removed surgically.

Myomas are benign tumors composed partly of muscle tissue. They seldom develop in the cervix, the lower part of the uterus. When they do, they are usually accompanied by myomas in the larger upper part of the uterus. Myomas in this part of the uterus are also called fibroids (see page 1533). Large cervical myomas may partially block the urinary tract or may protrude (prolapse) into the vagina. Sores sometimes develop on prolapsed myomas, which may become infected, bleed, or both. Prolapsed myomas can also block the flow of urine.

Symptoms

Most cervical myomas eventually cause symptoms. The most common symptom is bleeding from the vagina, which may be irregular or heavy. Heavy bleeding can cause anemia, with fatigue and weakness. Sexual intercourse may be painful.

If myomas become infected, they may cause pain, bleeding, or a discharge from the vagina. Rarely, prolapse causes symptoms such as a feeling of pressure or a lump in the abdomen.

If a myoma blocks the flow of urine, women may have a hesitant start when urinating, dribble at the end of urination, and retain urine. Urinary tract infections are more likely to develop.

Diagnosis

Doctors can often detect myomas during a physical examination. During a pelvic examination, doctors may see a myoma, particularly if prolapsed. Or doctors may feel a myoma when they check the size and shape of the uterus and cervix (with one gloved hand inside the vagina and the other on top of the abdomen).

If the diagnosis is uncertain, doctors may insert an ultrasound device through the vagina into the uterus to obtain an image of the area. This procedure, called transvaginal ultrasonography, is also done to check for blockage of urine flow and for additional myomas.

Blood tests are done to check for anemia. A Papanicolaou (Pap) test or variation of it (cervical cytology) is done to rule out cancer of the cervix.

Treatment

If myomas are small and do not cause any symptoms, no treatment is needed. If they cause symptoms, they are surgically removed if possible (a procedure called myomectomy). If only the myoma is removed, women can still bear children. However, if myomas are large, removal of the entire uterus (hysterectomy) may be necessary. Either procedure can be done by making a large incision in the abdomen (laparotomy). Sometimes these procedures can be done with instruments inserted through one or more small incisions near the navel (laparoscopy).

If a myoma prolapses, it is removed with instruments inserted through the vagina (transvaginally) if possible.

Cervical Stenosis

Cervical stenosis is narrowing of the passageway through the cervix (the lower part of the uterus).

Infertility can occur, or the uterus can fill with blood or pus.

Infertility can occur, or the uterus can fill with blood or pus.

The opening of the cervix can be widened to relieve symptoms.

The opening of the cervix can be widened to relieve symptoms.

In cervical stenosis, the passageway through the cervix (from the vagina to the main body of the uterus) is narrow or completely closed.

Some women are born with cervical stenosis. In others, cervical stenosis results from a disorder or another condition, such as the following:

Cancer (cervical or endometrial)

Cancer (cervical or endometrial)

Surgery to treat precancerous changes of the cervix (dysplasia)

Surgery to treat precancerous changes of the cervix (dysplasia)

Procedures that destroy or remove the lining of the uterus (endometrial ablation) in women who have persistent vaginal bleeding

Procedures that destroy or remove the lining of the uterus (endometrial ablation) in women who have persistent vaginal bleeding

Radiation therapy to treat cancer of the cervix or of the lining of the uterus (endometrial cancer)

Radiation therapy to treat cancer of the cervix or of the lining of the uterus (endometrial cancer)

Menopause, because the tissues in the cervix thin (atrophy)

Menopause, because the tissues in the cervix thin (atrophy)

Cervical stenosis may result in an accumulation of blood in the uterus (hematometra). In women who are still menstruating, menstrual blood mixed with cells from the uterus may flow backward into the pelvis, possibly causing endometriosis (see page 1529). If pus forms in the uterus (as it may in women with cervical or endometrial cancer), pus may accumulate in the uterus. Accumulation of pus in the uterus is called pyometra.

Symptoms

Before menopause, cervical stenosis may cause menstrual abnormalities, such as no periods (amenorrhea), painful periods (dysmenorrhea), and abnormal bleeding. Cervical stenosis can also cause infertility because sperm cannot pass through the cervix to fertilize the egg.

After menopause, cervical stenosis may be present but not cause symptoms.

A hematometra or pyometra can cause pain or cause the uterus to bulge. Sometimes women feel a lump in the pelvic area.

Diagnosis

Doctors suspect the diagnosis based on symptoms and circumstances, such as the following:

When periods stop or become painful after surgery on the cervix

When periods stop or become painful after surgery on the cervix

When doctors cannot insert an instrument into the cervix to obtain a sample of tissue from the cervix for a Papanicolaou (Pap) test or a variation of it (cervical cytology) or from the lining of the uterus (an endometrial biopsy)

When doctors cannot insert an instrument into the cervix to obtain a sample of tissue from the cervix for a Papanicolaou (Pap) test or a variation of it (cervical cytology) or from the lining of the uterus (an endometrial biopsy)

Doctors confirm the diagnosis by trying to pass a probe through the cervix into the uterus.

No further tests are needed for the following:

Postmenopausal women who have never had abnormal Pap test results

Postmenopausal women who have never had abnormal Pap test results

Women who have no symptoms, no hematometra, and no pyometra

Women who have no symptoms, no hematometra, and no pyometra

If cervical stenosis causes symptoms, a hematometra, or a pyometra, tissue samples are taken and examined under a microscope to rule out cancer. After treatment (which widens the cervix), doctors take samples from the cervix and from the uterine lining.

Treatment

Cervical stenosis is treated only if women have symptoms, a hematometra, or a pyometra. Then, the cervix may be widened (dilated) by inserting small, lubricated metal rods (dilators) through its opening, then inserting progressively larger dilators. To try to keep the cervix open, doctors may place a tube (cervical stent) in the cervix for 4 to 6 weeks.

Cysts

Cysts are closed sacs that are separate from the tissue around them. They often contain fluid or semisolid material. Cysts that commonly occur in the genital organs include Bartholin’s gland cysts, endometriomas, inclusion and epidermal cysts, and Skene’s duct cysts.

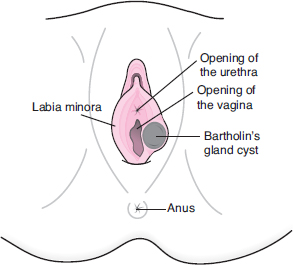

BARTHOLIN’S GLAND CYSTS

Bartholin’s gland cysts are mucus-filled sacs that can form when the glands located near the opening to the vagina are blocked.

Cysts are usually painless, but if large, they can interfere with sitting, walking, and sexual intercourse.

Cysts are usually painless, but if large, they can interfere with sitting, walking, and sexual intercourse.

Cysts may become infected, forming a painful abscess.

Cysts may become infected, forming a painful abscess.

Doctors can usually see or feel the cysts during a pelvic examination.

Doctors can usually see or feel the cysts during a pelvic examination.

Doctors may create a permanent opening from the cyst to the outside or may surgically remove the cyst.

Doctors may create a permanent opening from the cyst to the outside or may surgically remove the cyst.

Bartholin’s glands are very small, round glands that are located in the vulva on either side of the opening to the vagina. Because they are located deep under the skin, they cannot normally be felt. These glands may help provide fluids for lubrication during sexual intercourse.

If the duct to the gland is blocked, the gland becomes filled with mucus and enlarges. The result is a cyst. These cysts develop in about 2% of women, usually those in their 20s. As women age, they are less likely to have cysts and abscesses.

Typically, what causes the blockage is unknown. Rarely, cysts result from a sexually transmitted disease, such as gonorrhea.

Symptoms

Most cysts do not cause any symptoms. But if cysts become large, they can cause discomfort during sitting, walking, or sexual intercourse. Women may notice a painless lump near the opening of the vagina, making the vulva look lopsided.

Abscesses cause severe pain and sometimes fever. They are tender to the touch. The skin over them appears red. Women may have a discharge from the vagina, which is usually unrelated to the abscess.

Diagnosis

A woman should see a doctor in the following circumstances:

The cyst continues to enlarge or persists after several days of immersing the area in hot water (in a tub or sitz bath).

The cyst continues to enlarge or persists after several days of immersing the area in hot water (in a tub or sitz bath).

The cyst is painful (often indicating an abscess).

The cyst is painful (often indicating an abscess).

A fever develops.

A fever develops.

The cyst interferes with walking or sitting.

The cyst interferes with walking or sitting.

She is over 40.

She is over 40.

If a cyst is large enough for a woman to notice it or for symptoms to develop, doctors can usually see or feel the cyst during a pelvic examination. Doctors can usually tell whether it is infected by its appearance. If a discharge is present, doctors may send a sample to be tested for other infections.

Because cancer of the vulva sometimes resembles a cyst, doctors may remove the cyst to examine under a microscope (biopsy). A biopsy is usually done if the cyst is irregular or bumpy or if the woman is over 40.

Treatment

If a cyst causes little or no pain, women may treat it themselves. They can use a sitz bath or soak in a few inches of warm water in a tub. Soaks should last 10 to 15 minutes and be done 3 or 4 times a day. Sometimes cysts disappear after a few days of such treatment. If the treatment is ineffective, women should see a doctor.

In women under 40, only cysts that cause symptoms require treatment. Draining the cysts is usually ineffective because they commonly recur. Thus, surgery may be done to make a permanent opening from the gland’s duct to the surface of the vulva. Thus, if fluids refill the cyst, they can drain out. After a local anesthetic is injected to numb the site, one of the following procedures can be done:

Placement of a catheter: A small incision is made in the cyst so that a small balloon-tipped tube (catheter) can be inserted into the cyst. Once in place, the balloon is inflated, and the catheter is left there for 4 to 6 weeks, so that a permanent opening can form. The catheter is inserted and removed in the doctor’s office. Women can do their normal activities while the catheter is in place, although sexual intercourse may be uncomfortable.

Placement of a catheter: A small incision is made in the cyst so that a small balloon-tipped tube (catheter) can be inserted into the cyst. Once in place, the balloon is inflated, and the catheter is left there for 4 to 6 weeks, so that a permanent opening can form. The catheter is inserted and removed in the doctor’s office. Women can do their normal activities while the catheter is in place, although sexual intercourse may be uncomfortable.

Marsupialization: Doctors make a small cut in the cyst and stitch the inside edges of the cyst to the surface of the vulva. This procedure is done in an outpatient operating room. Sometimes general anesthesia is needed.

Marsupialization: Doctors make a small cut in the cyst and stitch the inside edges of the cyst to the surface of the vulva. This procedure is done in an outpatient operating room. Sometimes general anesthesia is needed.

What Is Bartholin’s Gland Cyst?

The small glands on either side of the vaginal opening, called Bartholin’s glands, may become blocked. Fluids then accumulate, and the gland swells, forming a cyst. Cysts range from the size of a pea to that of a golf ball or larger. Most often, they occur only on one side. They may become infected, forming an abscess.

After these procedures, women may have a discharge for a few weeks. Usually, wearing panty liners is all that is needed. Taking sitz baths several times a day may help relieve any discomfort and help speed healing.

If cysts recur, they may be surgically removed. This procedure is done in an operating room.

In women over 40, all cysts must be treated. Treatment usually occurs during diagnosis, when doctors obtain a sample to check for cancer. Treatment involves surgically removing or marsupializing the cyst.

For an abscess, antibiotics are given by mouth for 7 to 10 days. A catheter can be inserted to drain the abscess or marsupialization may be done initially to treat the abscess or later to prevent the cyst from refilling.

Regardless of treatment, cysts sometimes recur.

ENDOMETRIOMAS OF THE VULVA

Vulvar endometriomas are rare, painful, blood-filled cysts that develop when tissue from the lining of the uterus (endometrial tissue) appears in the vulva.

For unknown reasons, patches of tissue from the lining of the uterus (endometrial tissue) sometimes appear outside the uterus. This disorder is called endometriosis (see page 1529). Endometriosis rarely occurs in the vulva. It is more common in other locations, such as the ovaries. Sometimes the endometrial tissue forms a cyst (endometrioma). Endometriomas often develop at the site of a previous operation, such as an episiotomy (an incision to widen the opening of the vagina to help with delivery of a baby).

Endometriomas may be painful, particularly during intercourse. Endometriomas respond to hormones just as normal endometrial tissue does. Thus, they can enlarge and cause pain, particularly before and during menstrual periods. Endometriomas are tender and may look blue. They can rupture, causing severe pain.

During a pelvic examination, doctors can usually see or feel endometriomas that cause symptoms.

Endometriomas in the vulva are surgically removed. This procedure is usually done in an operating room but may be done in a doctor’s office. A local anesthetic is used. Doctors do a biopsy of the removed tissue to make sure it is not a melanoma, which can occur on the vulva and vagina.

INCLUSION AND EPIDERMAL CYSTS OF THE VULVA

Cysts that develop on the vulva include inclusion cysts and epidermal cysts. Vulvar inclusion cysts are small sacs that contain tissue from the surface of the vulva. Vulvar epidermal cysts are similar but contain secretions from oil-producing (sebaceous) glands near hair follicles.

Inclusion cysts are the most common cysts of the vulva. The vulva is the area that contains the external genital organs (see page 1491). Inclusion cysts may also develop in the vagina. They may result from injuries, such as tears caused during delivery of a baby. When the vulva is injured, tissue from its surface (epithelial tissue) may be trapped under the surface. Some inclusion cysts develop on their own.

Epidermal cysts may develop when the ducts to sebaceous glands become blocked. Secretions from these glands then accumulate under the skin’s surface.

Both of these cysts eventually enlarge and sometimes become infected.

Cysts that do not become infected usually cause no symptoms, but they occasionally cause irritation. They are white or yellow and usually less than ½ inch (about 1 centimeter) in diameter. Infected cysts may be red and tender and make sexual intercourse painful.

Doctors can usually see or feel cysts during a pelvic examination.

If cysts cause symptoms, they are removed after a local anesthetic is injected to numb the site.

SKENE’S DUCT CYST

Skene’s duct cysts develop near the opening of the urethra when the ducts to the glands are blocked.

Large cysts may cause pain during sexual intercourse or problems urinating.

Large cysts may cause pain during sexual intercourse or problems urinating.

Cysts that cause symptoms can be removed.

Cysts that cause symptoms can be removed.

Skene’s glands, also called periurethral or paraurethral glands, are located around the opening of the urethra. The tissue that surrounds them includes part of the clitoris. The glands may be involved in sexual stimulation and lubrication for sexual intercourse.

Cysts are uncommon. They form if the duct to the gland is blocked, usually because the gland is infected. These cysts occur mainly in adults. If cysts become infected, they may form an abscess.

Symptoms

Most cysts are less than ½ inch (about 1 centimeter) in diameter and do not cause any symptoms. Some cysts are larger and cause pain during sexual intercourse. Sometimes large cysts block the flow of urine through the urethra. In such cases, the first symptoms may be a hesitant start when urinating, dribbling at the end of urination, and retention of urine. Or a urinary tract infection may develop, causing a frequent, urgent need to urinate and painful urination.

Abscesses are tender, painful, and swollen. The skin over the ducts appears red. Most women do not have a fever.

Diagnosis

During a pelvic examination, doctors can usually feel cysts or abscesses if they are large enough to cause symptoms. However, ultrasonography may be done or a flexible viewing tube to view the bladder (cystoscopy) may be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

If cysts cause symptoms, they are removed, usually in a doctor’s office or in an operating room. In the office, a local anesthetic is usually used.

For abscesses, antibiotics are given by mouth for 7 to 10 days. Then, the cyst is removed. Or doctors may make a small cut in the cyst and stitch the edges of the cyst to the surface of the vulva (marsupialization) so that it can drain.

Noncancerous Ovarian Growths

Noncancerous (benign) ovarian growths include functional cysts and tumors.

Most noncancerous cysts and tumors do not cause any symptoms, but some cause pain or a feeling of heaviness in the pelvis.

Most noncancerous cysts and tumors do not cause any symptoms, but some cause pain or a feeling of heaviness in the pelvis.

Doctors may detect growths during a pelvic examination, then use ultrasonography to confirm the diagnosis.

Doctors may detect growths during a pelvic examination, then use ultrasonography to confirm the diagnosis.

Some cysts disappear on their own.

Some cysts disappear on their own.

Cysts or tumors may be removed through an incision in the abdomen, and sometimes the affected ovary must also be removed.

Cysts or tumors may be removed through an incision in the abdomen, and sometimes the affected ovary must also be removed.

Functional Cysts: Functional cysts form from the fluid-filled cavities (follicles) in the ovaries. Each follicle contains one egg. Usually, during each menstrual cycle, one follicle releases one egg. About one third of women who are menstruating have cysts. Functional cysts seldom develop after menopause.

There are two types of functional cysts:

Follicular cysts: These cysts form as the egg is developing in the follicle.

Follicular cysts: These cysts form as the egg is developing in the follicle.

Corpus luteum cysts: These cysts develop from the structure that forms after the follicle ruptures and releases its egg. This structure is called the corpus luteum. Corpus luteum cysts may bleed, causing the ovary to bulge or to rupture. If the cyst ruptures, fluids escape into spaces in the abdomen (the abdominal cavity) and may cause severe pain.

Corpus luteum cysts: These cysts develop from the structure that forms after the follicle ruptures and releases its egg. This structure is called the corpus luteum. Corpus luteum cysts may bleed, causing the ovary to bulge or to rupture. If the cyst ruptures, fluids escape into spaces in the abdomen (the abdominal cavity) and may cause severe pain.

Most functional cysts are less than about ⅔ inch (1.5 centimeters) in diameter. A few reach or exceed about 2 inches (5 centimeters). Functional cysts usually disappear on their own after a few days or weeks.

Benign Tumors: Noncancerous (benign) ovarian tumors usually grow slowly and rarely become cancerous. The most common include the following:

Benign cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts): These tumors usually develop from all three layers of tissue in the embryo (called germ cell layers). All organs form from these tissues. Thus, teratomas may contain tissues from other structures, such as nerve, glandular, and skin tissues.

Benign cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts): These tumors usually develop from all three layers of tissue in the embryo (called germ cell layers). All organs form from these tissues. Thus, teratomas may contain tissues from other structures, such as nerve, glandular, and skin tissues.

Fibromas: These tumors are solid masses composed of connective tissue (the tissues that hold structures together). Fibromas are slow-growing and are usually less than 3 inches (about 7 centimeters) in diameter. They usually occur on only one side.

Fibromas: These tumors are solid masses composed of connective tissue (the tissues that hold structures together). Fibromas are slow-growing and are usually less than 3 inches (about 7 centimeters) in diameter. They usually occur on only one side.

Cystadenomas: These fluid-filled cysts develop from the surface of the ovary and contain some tissue from glands in the ovaries.

Cystadenomas: These fluid-filled cysts develop from the surface of the ovary and contain some tissue from glands in the ovaries.

Symptoms

Most functional cysts and noncancerous tumors do not cause any symptoms. Sometimes women have irregular periods and spotting. If corpus luteum cysts bleed, they may cause pain or tenderness in the pelvic area. If women have a fever, feel nauseated, and vomit, the spaces in the abdomen (abdominal cavity) and the tissues lining it may be infected (a disorder called peritonitis). Occasionally, sudden, severe abdominal pain occurs because a large cyst or mass causes the ovary to twist (a disorder called adnexal torsion).

Accumulation of fluid in the abdomen (ascites) can occur with fibromas and ovarian cancer. Ascites may cause a feeling of pressure or heaviness in the abdomen.

Diagnosis

Doctors usually detect cysts or tumors during a routine pelvic examination. But sometimes doctors suspect them based on symptoms.

A pregnancy test is done to rule out pregnancy, including pregnancy located outside the uterus (ectopic pregnancy). Ultrasonography using an ultrasound device inserted into the vagina (transvaginal ultrasonography) is done to confirm the diagnosis. If the diagnosis is still unclear, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) may be done. If these tests suggest that the growth could be cancerous, doctors remove it and examine it under a microscope. They may also do blood tests to check for substances called markers, which may appear in the blood or may increase when some cancers are present.

Treatment

If ovarian cysts are less than 3 inches (about 7 centimeters) in diameter, they usually disappear without treatment. Ultrasonography is done periodically to check.

If a cyst or tumor needs to be removed, laparoscopy or laparotomy is done if possible. Laparoscopy requires two or three small incisions in the abdomen. It is done in a hospital and usually requires a general anesthetic. However, women do not have to stay overnight. Laparotomy is similar but requires a larger incision and an overnight stay in the hospital. Which procedure is used depends on how large the growth is and whether other organs are affected. Cystectomy (removal of the cyst) can usually be done for the following conditions:

Most cysts that are larger than 3 inches and that persist for more than three menstrual cycles

Most cysts that are larger than 3 inches and that persist for more than three menstrual cycles

Cystic teratomas that are smaller than 4 inches (about 10 centimeters)

Cystic teratomas that are smaller than 4 inches (about 10 centimeters)

Corpus luteum cysts if peritonitis develops

Corpus luteum cysts if peritonitis develops

Removal of the affected ovary (oophorectomy) is necessary for the following:

Fibromas and solid ovarian tumors

Fibromas and solid ovarian tumors

Cystadenomas

Cystadenomas

Cystic teratomas that are larger than 4 inches

Cystic teratomas that are larger than 4 inches

Cysts that cannot be surgically separated from the ovary

Cysts that cannot be surgically separated from the ovary

Most cysts that are detected in postmenopausal women and are > 2 inches

Most cysts that are detected in postmenopausal women and are > 2 inches

Polyps of the Cervix

Cervical polyps are common fingerlike growths of tissue that protrude into the passageway through the cervix. Polyps are almost always benign (noncancerous).

About 2 to 5% of women have cervical polyps. They are probably caused by chronic inflammation or infection. They are rarely cancerous.

Most cervical polyps do not cause any symptoms. Some polyps bleed between menstrual periods or after intercourse. Some become infected, causing a puslike discharge from the vagina. Polyps are usually reddish pink and less than ½ inch (about 1 centimeter) in diameter.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Doctors can detect polyps when they do a pelvic examination.

Polyps that cause bleeding or a discharge are removed during the pelvic examination in the doctor’s office. No anesthetic is needed. Rarely, bleeding occurs after polyps are removed. If it does, a caustic substance, such as silver nitrate, is applied to the affected area with a swab to stop the bleeding.

If symptoms (bleeding and a discharge) persist after polyps are removed, a Papanicolaou (Pap) test or a variation of it (cervical cytology) is done to rule out cancer of the cervix. Also, a sample of tissue from the lining of the uterus (endometrium) is taken and examined under a microscope (endometrial biopsy) to exclude endometrial cancer.