CHAPTER 247

Cancers of the Female Reproductive System

Cancers can occur in any part of the female reproductive system—the vulva, vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, or ovaries. These cancers are called gynecologic cancers.

Gynecologic cancers can directly invade nearby tissues and organs or spread (metastasize) through the lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes (lymphatic system) or bloodstream to distant parts of the body.

Diagnosis

Regular pelvic examinations and Papanicolaou (Pap) tests or other similar tests (see page 1502) can lead to the early detection of certain gynecologic cancers, especially cancer of the cervix. Such examinations can sometimes prevent cancer by detecting precancerous changes (dysplasia) before they become cancer. Regular pelvic examinations can also detect early cancers of the vagina and vulva. However, cancers of the ovaries, uterus, and fallopian tubes are not easy for doctors to detect during a pelvic examination.

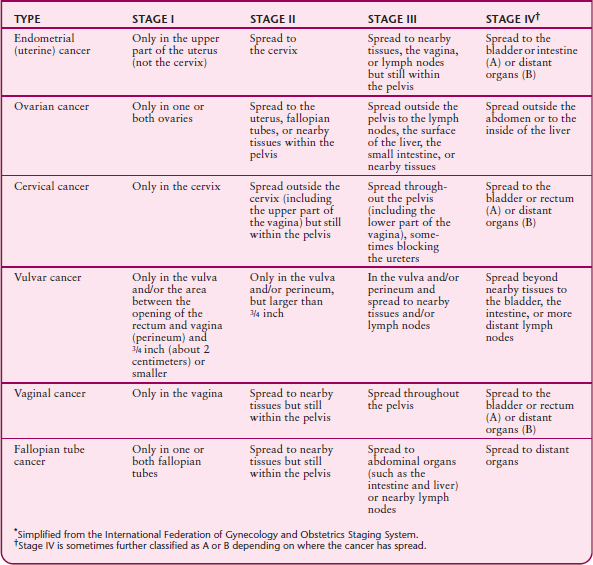

If cancer is suspected, a biopsy can confirm or rule out the diagnosis. If cancer is diagnosed, one or more procedures may be done to determine the stage of the cancer. The stage is based on how large the cancer is and how far it has spread. Some commonly used procedures include ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), chest x-rays, and bone scans using a radioactive substance.

Staging a cancer helps doctors choose the best treatment. Doctors often determine the stage of cancer after they remove the cancer and biopsy the surrounding tissues, including lymph nodes. For all gynecologic cancers, stages range from I (the earliest) to IV (advanced). For most cancers, further distinctions, designated by letters of the alphabet, are made within stages.

Treatment

The main treatment of endometrial or ovarian cancer is surgical removal of the tumor. Surgery may be followed by radiation therapy or chemotherapy. In women with cervical cancer, radiation therapy may be external (using a large machine) or internal (using radioactive implants placed directly on the cancer). External radiation therapy is usually given several days a week for several weeks. Internal radiation therapy involves staying in the hospital for several days while the implants are in place.

Chemotherapy may be given by injection or by mouth or by giving drugs through a catheter inserted into the abdomen (intraperitoneally). How often chemotherapy is given depends on the type of cancer. Sometimes women have to remain at the hospital while they receive chemotherapy.

When a gynecologic cancer is very advanced and a cure is not possible, radiation therapy or chemotherapy may still be recommended to reduce the size of the cancer or its metastases and to relieve pain and other symptoms. Women with incurable cancer should establish advance directives (see page 69). Because end-of-life care has improved, more and more women with incurable cancer are able to die comfortably at home (see page 60). Appropriate drugs can be used to relieve the anxiety and pain commonly experienced by people with incurable cancer.

Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial cancer of the uterus develops in the lining of the uterus (endometrium).

Endometrial cancer usually affects women after menopause.

Endometrial cancer usually affects women after menopause.

It sometimes causes abnormal vaginal bleeding.

It sometimes causes abnormal vaginal bleeding.

To diagnosis this cancer, doctors remove a sample of tissue from the endometrium to be analyzed (biopsy).

To diagnosis this cancer, doctors remove a sample of tissue from the endometrium to be analyzed (biopsy).

Usually, the uterus and fallopian tubes are removed, often followed by radiation therapy and sometimes by chemotherapy.

Usually, the uterus and fallopian tubes are removed, often followed by radiation therapy and sometimes by chemotherapy.

STAGING CANCERS OF THE FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM*

Cancer of the uterus begins in the lining of the uterus (endometrium) and is more precisely termed endometrial cancer (carcinoma). In the United States, it is the most common gynecologic cancer and the fourth most common cancer among women. One in 50 women gets endometrial cancer. This cancer usually develops after menopause, most often in women aged 50 to 65.

More than 80% of endometrial cancers are adenocarcinomas, which develop from gland cells. Fewer than 5% of cancers in the uterus are sarcomas. These cancers develop from connective tissue and tend to be more aggressive.

Causes

Endometrial cancer is more common in developed countries where the diet is high in fat.

The most important risk factors for endometrial cancer are

Obesity

Obesity

Diabetes

Diabetes

Hypertension

Hypertension

Other factors increase risk because they result in a high level of estrogen but not progesterone. They include the following:

Having an early start of menstrual periods (menarche), menopause after age 52, or both

Having an early start of menstrual periods (menarche), menopause after age 52, or both

Having menstrual problems (such as excessive bleeding, spotting between menstrual periods, or long intervals without periods)

Having menstrual problems (such as excessive bleeding, spotting between menstrual periods, or long intervals without periods)

Not having any children

Not having any children

Having tumors that produce estrogen

Having tumors that produce estrogen

Taking high doses of drugs that contain estrogen, such as estrogen therapy without a progestin (a synthetic drug similar to the hormone progesterone), after menopause

Taking high doses of drugs that contain estrogen, such as estrogen therapy without a progestin (a synthetic drug similar to the hormone progesterone), after menopause

Using tamoxifen for more than 5 years

Using tamoxifen for more than 5 years

Estrogen promotes the growth of tissue and rapid cell division in the lining of the uterus (endometrium). Progesterone helps balance the effects of estrogen. Levels of estrogen are high during part of the menstrual cycle. Thus, having more menstrual periods during a lifetime may increase the risk of endometrial cancer. Tamoxifen, a drug used to treat breast cancer, blocks the effects of estrogen in the breast, but it has the same effects as estrogen in the uterus. Thus, this drug may increase the risk of endometrial cancer. Taking oral contraceptives that contain estrogen and a progestin appears to reduce the risk of endometrial cancer.

Other risk factors include the following:

Having had or having a family member who has had cancer of the breast, ovaries, or possibly the large intestine (colon) or lining of the uterus

Having had or having a family member who has had cancer of the breast, ovaries, or possibly the large intestine (colon) or lining of the uterus

Having had radiation therapy directed at the pelvis

Having had radiation therapy directed at the pelvis

Symptoms

Abnormal bleeding from the vagina is the most common early symptom. Abnormal bleeding includes

Bleeding after menopause

Bleeding after menopause

Bleeding between menstrual periods

Bleeding between menstrual periods

Periods that are irregular, heavy, or longer than normal

Periods that are irregular, heavy, or longer than normal

One of three women with vaginal bleeding after menopause has endometrial cancer. Women who have vaginal bleeding after menopause should see a doctor promptly. A watery, blood-tinged discharge may also occur. Postmenopausal women may have a vaginal discharge for several weeks or months, followed by vaginal bleeding.

Diagnosis

Doctors may suspect endometrial cancer if women have typical symptoms or if results of a Papanicolaou (Pap) test, usually done as part of a routine examination, are abnormal. If cancer is suspected, doctors take a sample of tissue from the endometrium (endometrial biopsy) in their office and send it to a laboratory for analysis. This test accurately detects endometrial cancer more than 90% of the time. If the diagnosis is still uncertain, doctors scrape tissue from the uterine lining for analysis—a procedure called dilation and curettage (D and C— see page 1504). At the same time, doctors may view the interior of the uterus using a thin, flexible viewing tube inserted through the vagina and cervix into the uterus in a procedure called hysteroscopy. Alternatively, an ultrasound device may be inserted through the vagina into the uterus (transvaginal ultrasonography) to evaluate abnormalities.

If endometrial cancer is diagnosed, some or all of the following procedures may be done to determine whether the cancer has spread beyond the uterus: blood tests, kidney and liver function tests, and a chest x-ray. If results of the physical examination or other tests suggest that the cancer has spread beyond the uterus, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is done. Other procedures are sometimes required. Staging is based on information obtained from these procedures and during surgery to remove the cancer.

Prognosis

If endometrial cancer is detected early, nearly 70 to 95% of women who have it survive at least 5 years, and most are cured. The prognosis is better for women whose cancer has not spread beyond the uterus. If the cancer grows relatively slowly, the prognosis is also better. Less than one third of women who have this cancer die of it.

Treatment

Hysterectomy, surgical removal of the uterus, is the mainstay of treatment for women who have endometrial cancer. If the cancer has not spread beyond the uterus, removal of the uterus plus removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries (salpingo-oophorectomy) almost always cures the cancer. Unless the cancer is very advanced, hysterectomy improves the prognosis. Nearby lymph nodes are usually removed at the same time. These tissues are examined by a pathologist to determine whether the cancer has spread and, if so, how far it has spread. With this information, doctors can determine whether additional treatment (chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a progestin) is needed after surgery.

For very advanced cancer, treatment varies but usually involves a combination of surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and occasionally synthetic hormones.

Radiation therapy may be given after surgery in case some undetected cancer cells remain. More than half of women with cancer limited to the uterus do not need radiation therapy. However, if the cancer has spread to the cervix or beyond the uterus, radiation therapy is usually recommended after surgery.

If the cancer has spread beyond the uterus and cervix or recurs, chemotherapy drugs (such as carboplatin, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and paclitaxel) may be used instead of or sometimes with radiation therapy. These drugs reduce the cancer’s size and control its spread in more than half of women treated. However, these drugs are toxic and have many side effects.

If the cancer does not respond to chemotherapy, progestins (synthetic drugs similar to the hormone progesterone) may be used. These drugs are much less toxic than chemotherapy drugs. In 20 to 25% of women who have cancer that has spread or recurred, a progestin may reduce the cancer’s size and control its spread for 2 to 3 years. Treatment is continued as long as the cancer responds to it.

If menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes and vaginal dryness become bothersome after the uterus is removed, hormones such as estrogen, a progestin, or both can taken to relieve them. This treatment is safe and does not increase the risk of developing cancer again.

Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer may not cause symptoms until it is large or has spread.

Ovarian cancer may not cause symptoms until it is large or has spread.

If doctors suspect ovarian cancer, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography is done.

If doctors suspect ovarian cancer, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography is done.

Usually, both ovaries, both fallopian tubes, and the uterus are removed.

Usually, both ovaries, both fallopian tubes, and the uterus are removed.

Chemotherapy is often needed after surgery.

Chemotherapy is often needed after surgery.

Cancer of the ovaries (ovarian carcinoma) develops most often in women aged 50 to 70. This cancer eventually develops in about 1 of 70 women. In the United States, it is the second most common gynecologic cancer. However, more women die of ovarian cancer than of any other gynecologic cancer. It is the fifth most common cause of cancer deaths in women.

Factors that increase the risk of ovarian cancer include the following:

Understanding Hysterectomy

A hysterectomy is the removal of the uterus. Usually, the uterus is removed through an incision in the lower abdomen. Sometimes the uterus can be removed through the vagina. Either method usually takes about 1 to 2 hours and requires a general anesthetic. Afterward, vaginal bleeding and pain may occur. The hospital stay is usually 2 to 3 days, and recovery may take up to 6 weeks. When the uterus is removed through the vagina, less bleeding occurs, recovery is faster, and there is no visible scar.

Because of advances in technology, hysterectomy may be done using laparoscopy or robotic surgery. Then, the hospital stay is only 1 day. Women usually have less pain after surgery and can return more quickly to normal activities.

In addition to treating certain gynecologic cancers, a hysterectomy may be used to treat prolapse of the uterus, endometriosis, or fibroids (if causing severe symptoms). Sometimes it is done as part of the treatment for cancer of the colon, rectum, or bladder.

There are several types of hysterectomy. The type used depends on the disorder being treated.

Subtotal (supracervical) hysterectomy: Only the upper part of the uterus is removed, but the cervix is not. The fallopian tubes and ovaries may or may not be removed.

Subtotal (supracervical) hysterectomy: Only the upper part of the uterus is removed, but the cervix is not. The fallopian tubes and ovaries may or may not be removed.

Total hysterectomy: The entire uterus including the cervix is removed.

Total hysterectomy: The entire uterus including the cervix is removed.

Radical hysterectomy: The entire uterus plus the surrounding tissues, ligaments, and lymph nodes are removed. Both fallopian tubes and ovaries are usually also removed in women older than 45.

Radical hysterectomy: The entire uterus plus the surrounding tissues, ligaments, and lymph nodes are removed. Both fallopian tubes and ovaries are usually also removed in women older than 45.

After a hysterectomy, menstruation stops. However, a hysterectomy does not cause menopause unless the ovaries are removed also. Removal of the ovaries has the same effects as menopause, so hormone therapy may be recommended (see page 1516). Many women anticipate feeling depressed or losing interest in sex after a hysterectomy. However, hysterectomy rarely has these effects unless the ovaries are also removed.

Being older (the most important)

Being older (the most important)

Not having any children

Not having any children

Having a first child late in life

Having a first child late in life

Starting menstruating early

Starting menstruating early

Having menopause late

Having menopause late

Having had or having a family member who had cancer of the uterus, breast, or large intestine (colon)

Having had or having a family member who had cancer of the uterus, breast, or large intestine (colon)

The risk of ovarian cancer is higher in developed countries because the diet tends to be high in fat. Use of oral contraceptives significantly decreases risk.

About 5 to 10% of cases are related to the BRCA gene, which is also involved in some breast cancers. In these cases, ovarian and breast cancer tends to run in families. This abnormal gene is most common among Ashkenazi Jewish women.

There are many types of ovarian cancer. They develop from the many different types of cells in the ovaries. Cancers that start on the surface of the ovaries (epithelial carcinomas) account for at least 80%. Most other ovarian cancers start from the cells that produce eggs (called germ cell tumors) or in connective tissue (called stromal cell tumors). Germ cell tumors are much more common among women younger than 30. Sometimes cancers from other parts of the body spread to the ovaries.

Ovarian cancer can spread directly to the surrounding area and through the lymphatic system to other parts of the pelvis and abdomen. It can also spread through the bloodstream, eventually appearing in distant parts of the body, mainly the liver and lungs.

Symptoms

Ovarian cancer causes the affected ovary to enlarge. In young women, enlargement of an ovary is likely to be caused by a noncancerous fluid-filled sac (cyst). However, after menopause, an enlarged ovary can be a sign of ovarian cancer.

Many women have no symptoms until the cancer is advanced. The first symptom may be vague discomfort in the lower abdomen, similar to indigestion. Other symptoms may include bloating, loss of appetite (because the stomach is compressed), gas pains, and backache. Ovarian cancer rarely causes vaginal bleeding.

Eventually, the abdomen may swell because the ovary enlarges or fluid accumulates in the abdomen. At this stage, pain in the pelvic area, anemia, and weight loss are common. Rarely, germ cell or stromal cell tumors produce estrogens, which can cause tissue in the uterine lining to grow excessively and breasts to enlarge. Or these tumors may produce male hormones (androgens), which can cause body hair to grow excessively, or hormones that resemble thyroid hormones, which can cause hyperthyroidism.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing ovarian cancer in its early stages is difficult because symptoms usually do not appear until the cancer is quite large or has spread beyond the ovaries and because many less serious disorders cause similar symptoms.

If doctors detect an enlarged ovary during a physical examination, ultrasonography is done first. Sometimes computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to help distinguish an ovarian cyst from a cancerous mass. If advanced cancer is suspected, CT or MRI is usually done before surgery to determine extent of the cancer.

If cancer seems unlikely, doctors reexamine the woman periodically.

If doctors suspect cancer or test results are unclear, the ovaries are examined using a thin, flexible viewing tube (laparoscope) inserted through a small incision just below the navel. Also, tissue samples are removed using instruments threaded through the laparoscope and examined (biopsied). In addition, blood tests are usually done to measure levels of substances that may indicate the presence of cancer (tumor markers), such as cancer antigen 125 (CA 125). Abnormal marker levels alone do not confirm the diagnosis of cancer, but when combined with other information, they can help confirm it.

If fluid has accumulated in the abdomen, it can be drawn out (aspirated) through a needle and tested to determine whether cancer cells are present.

If doctors suspect advanced cancer or cancer is confirmed, they make an incision in the abdomen to obtain a tissue sample. At the same time, they remove as much of the cancer as possible and determine how far the cancer has spread (its stage).

Prognosis

The prognosis is based on the stage (see table on page 1571). The percentages of women who are alive 5 years after diagnosis and treatment are

Stage I: 70 to 100%

Stage I: 70 to 100%

Stage II: 50 to 70%

Stage II: 50 to 70%

Stage III: 20 to 50%

Stage III: 20 to 50%

Stage IV: 10 to 20%

Stage IV: 10 to 20%

The prognosis is worse when the cancer is more aggressive or when surgery cannot remove all visibly abnormal tissue. Cancer recurs in 70% of women who have had stage III or IV cancer.

Prevention

Some experts believe that if ovarian or breast cancer runs in the family, women should be tested for genetic abnormalities. If first- or second-degree relatives have such cancers, particularly among Ashkenazi Jewish families, women should discuss genetic testing for BRCA abnormalities with their doctors. Women with certain BRCA gene mutations may be offered the option of having both ovaries and tubes removed after they no longer wish to bear children, even when no cancer is present. This approach eliminates the risk of ovarian cancer and reduces the risk of breast cancer. These women should be evaluated by a gynecologist who specializes in cancer (gynecologic oncologist). More information is available from the National Cancer Institute Cancer Information Service (1-800-4-CANCER) and the Women’s Cancer Network (WCN) web site (www.wcn.org).

What Is an Ovarian Cyst?

An ovarian cyst is a fluid-filled sac in or on an ovary. Such cysts are relatively common. Most are noncancerous and disappear on their own. Cancerous cysts are more likely to occur in women older than 40.

Most noncancerous ovarian cysts do not cause symptoms. However, some cause pressure, aching, or a feeling of heaviness in the abdomen. Pain may be felt during sexual intercourse. If a cyst ruptures or becomes twisted, severe stabbing pain is felt in the abdomen. The pain may be accompanied by nausea and fever. Some cysts produce hormones that affect menstrual periods. As a result, periods may be irregular or heavier than normal. In postmenopausal women, such cysts may cause vaginal bleeding. Women who have any of these symptoms should see a doctor.

Doctors may find a cyst during a routine pelvic examination or occasionally suspect it based on symptoms. A pregnancy test is done to exclude that possibility. An ultrasound device may be inserted through the vagina into the uterus (transvaginal ultrasonography) to confirm the diagnosis.

If the cyst appears to be noncancerous, a woman may be asked to return periodically for pelvic examinations as long as the cyst remains. If the cyst could be cancerous, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be done. If cancer still seems possible, the ovaries may be examined through a laparoscope, inserted through a small incision just below the navel. Blood tests can help confirm or rule out cancer.

For noncancerous cysts, no treatment is necessary. But if a cyst is larger than about 2 inches (5 centimeters) and persists, it may need to be removed. If cancer cannot be ruled out, the ovary is removed. Cancerous cysts plus the affected ovary and fallopian tube are removed.

Surgery may be done through a laparoscope (with only a small incision) or a larger incision in the abdomen.

Treatment

The extent of surgery depends on the type of ovarian cancer and the stage. For most cancers, the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and uterus are removed. When cancer has spread beyond the ovary, nearby lymph nodes and surrounding structures that the cancer typically spreads to are also removed. If a woman has stage I cancer that affects only one ovary and she wishes to become pregnant, doctors may remove only the affected ovary and fallopian tube. For more advanced cancers that have spread to other parts of the body, removing as much of the cancer as possible prolongs survival.

After surgery, most women with stage I epithelial carcinomas usually require no further treatment. For other stage I cancers or for more advanced cancers, chemotherapy may be used to destroy any small areas of cancer that may remain. Typically, chemotherapy consists of paclitaxel combined with carboplatin, given 6 times. Most women with germ cell tumors can be cured with removal of the one affected ovary and fallopian tube plus combination chemotherapy, usually with bleomycin, cisplatin, and etoposide. Radiation therapy is rarely used.

Advanced ovarian cancer usually recurs. So after chemotherapy, doctors typically measure levels of cancer markers. If the cancer recurs, chemotherapy (using drugs such as carboplatin, doxorubicin, etoposide, gemcitabine, paclitaxel, or topotecan) is given.

Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer develops in the cervix (the lower part of the uterus).

Cervical cancer usually results from infection with the human papillomavirus, transmitted during sexual intercourse.

Cervical cancer usually results from infection with the human papillomavirus, transmitted during sexual intercourse.

Cervical cancer may cause irregular vaginal bleeding, but symptoms may not occur until the cancer has enlarged or spread.

Cervical cancer may cause irregular vaginal bleeding, but symptoms may not occur until the cancer has enlarged or spread.

Papanicolaou (Pap) tests can usually detect abnormalities, which are then biopsied.

Papanicolaou (Pap) tests can usually detect abnormalities, which are then biopsied.

Treatment usually involves removing the cancer and often surrounding tissue, often with radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Treatment usually involves removing the cancer and often surrounding tissue, often with radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Getting regular Pap tests and being vaccinated against HPV can prevent cervical cancer.

Getting regular Pap tests and being vaccinated against HPV can prevent cervical cancer.

The cervix is the lower part of the uterus. It extends into the vagina. In the United States, cervical cancer (cervical carcinoma) is the third most common gynecologic cancer among all women and the most common among younger women. It usually affects women aged 35 to 55, but it can affect women as young as 20.

This cancer is usually caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which is transmitted during sexual intercourse. This virus also causes genital warts (see page 1267). The younger a woman was the first time she had sexual intercourse and the more sex partners she has had, the higher her risk of cervical cancer. Risk is also increased by having intercourse with men whose previous partners had cervical cancer, by smoking cigarettes, and by having a weakened immune system (due to a disorder such as cancer or AIDS or to drugs such as chemotherapy drugs or corticosteroids).

About 80 to 85% of cervical cancers are squamous cell carcinomas, which develop in the flat, skinlike cells covering the cervix. Most other cervical cancers are adenocarcinomas, which develop from gland cells.

Cervical cancer begins with slow, progressive changes in normal cells on the surface of the cervix. These changes, called dysplasia or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), are considered precancerous. That means that if untreated, they may progress to cancer, sometimes after years.

Cervical cancer begins on the surface of the cervix and can penetrate deep beneath the surface. The cancer can spread directly to nearby tissues, including the vagina. Or it can enter the rich network of small blood and lymphatic vessels inside the cervix, then spread to other parts of the body.

Symptoms

Precancerous changes usually cause no symptoms. In the early stages, cervical cancer may cause no symptoms or cause abnormal bleeding from the vagina, most often after intercourse. Spotting or heavier bleeding may occur between periods, or periods may be unusually heavy. Large cancers are more likely to cause bleeding and may cause a foul-smelling discharge from the vagina and pain in the pelvic area.

If the cancer is widespread, it can cause lower back pain and swelling of the legs. The urinary tract may be blocked, and without treatment, kidney failure and death can result.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Pap tests have reduced the number of deaths due to cervical cancer by more than 50%.

If all women had Pap tests regularly, deaths due to this cancer could be virtually eliminated.

Diagnosis

Routine Pap tests or other similar tests can detect the beginnings of cervical cancer (see page 1502). Pap tests accurately detect up to 90% of cervical cancers, even before symptoms develop. They can also detect dysplasia. Women with dysplasia should be checked again in 3 to 4 months. Dysplasia can be treated, thus helping prevent cancer.

If a growth, a sore, or another abnormal area is seen on the cervix during a pelvic examination or if a Pap test detects dysplasia or cancer, a biopsy is done. Usually, doctors use an instrument with a binocular magnifying lens (colposcope), inserted through the vagina, to examine the cervix and to choose the best biopsy site. Two different types of biopsy are done:

Punch biopsy: A tiny piece of the cervix, selected using the colposcope, is removed.

Punch biopsy: A tiny piece of the cervix, selected using the colposcope, is removed.

Endocervical curettage: Tissue that cannot be viewed is scraped from inside the cervix.

Endocervical curettage: Tissue that cannot be viewed is scraped from inside the cervix.

These biopsies cause little pain and a small amount of bleeding. The two together usually provide enough tissue for pathologists to make a diagnosis.

If the diagnosis is not clear, a cone biopsy is done to remove a larger cone-shaped piece of tissue. Usually, a thin wire loop with an electrical current running through it is used. This procedure is called the loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). Alternatively, a laser (using a highly focused beam of light) can be used. Either procedure requires only a local anesthetic and can be done in the doctor’s office. A cold (nonelectric) knife is sometimes used, but this procedure requires an operating room and an anesthetic.

If cervical cancer is diagnosed, its exact size and locations (its stage) are determined. Staging begins with a physical examination of the pelvis. Various procedures (such as cystoscopy, a chest x-ray, and sigmoidoscopy) can be used to determine whether the cancer has spread to nearby tissues or to distant parts of the body. Other procedures, such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a barium enema, bone and liver scans, and positron emission tomography (PET) may be done.

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the stage of the cancer (see table on page 1571). The percentages of women who are alive 5 years after diagnosis and treatment are

Stage I: 80 to 90% of women

Stage I: 80 to 90% of women

Stage II: 60 to 75%

Stage II: 60 to 75%

Stage III: 30 to 40%

Stage III: 30 to 40%

Stage IV: 15% or fewer

Stage IV: 15% or fewer

If the cancer is going to recur, it usually does so within 2 years.

Prevention

Pap Tests: The number of deaths due to cervical cancer has been reduced by more than 50% since Pap tests were introduced. Doctors often recommend that women have their first Pap test when they become sexually active or reach the age of 18 and that a Pap test be done once a year. If test results are normal for 3 consecutive years, women may schedule Pap tests every 2 or 3 years as long as they do not change their sexual lifestyle. Any woman who has had cervical cancer or dysplasia should continue to have Pap tests at least once a year. If all women had Pap tests on a regular basis, deaths due to this cancer could be virtually eliminated. However, in the United States, about 50% of women are not tested regularly.

HPV Vaccine: A newly developed vaccine targets the types of HPV that cause most cervical cancer (and genital warts). The vaccine can help prevent cervical cancer but does not treat it. Three doses of the vaccine are given (see page 1148). The first is followed by one 2 months and one 6 months after the first. Being vaccinated before becoming sexually active is best, but even if women are already sexually active, they should be vaccinated. (Using condoms during intercourse can help prevent spread of HPV.)

Treatment

Treatment depends on the stage of the cancer.

Early Stages: If only the surface of the cervix is involved, doctors can often completely remove the cancer by removing part of the cervix using the loop electrosurgical excision procedure, a laser, or a cold knife, done during a cone biopsy. These treatments preserve a woman’s ability to have children. Because cancer can recur, doctors advise women to return for examinations and Pap tests every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months after that. Rarely, removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) is necessary.

If early-stage cancer involves more than the surface of the cervix, doctors usually do a hysterectomy and give radiation therapy and chemotherapy. If women with early-stage cervical cancer wish to preserve their ability to have children, a procedure called radical trachelectomy may be done. In this procedure, the cervix, the tissue next to the cervix, the upper part of the vagina, and the lymph nodes in the pelvis are removed. The uterus and vagina that remain are attached to each other. Thus, women still can become pregnant. However, babies must be delivered by cesarean section. This treatment appears to be as effective as other more invasive treatments for women with early-stage cervical cancer.

Initial Spread Within the Pelvis: Hysterectomy plus removal of surrounding tissues, ligaments, and lymph nodes (radical hysterectomy) is necessary. The ovaries may be removed. Normal, functioning ovaries in younger women are not removed. Radiation therapy may be used sometimes instead of hysterectomy. Radiation therapy may irritate the bladder or rectum. Later, as a result, the intestine may become blocked, and the bladder and rectum may be damaged. Also, the ovaries usually stop functioning. With either radical hysterectomy or radiation therapy, chemotherapy is usually also used, and about 85 to 90% of women are cured.

Further Spread Within the Pelvis or to Other Organs: Radiation therapy plus chemotherapy (with cisplatin) is preferred. A laparoscope may be used or surgery done to determine whether lymph nodes are involved and thus determine where radiation should be directed.

If the cancer remains in the pelvis after radiation therapy, doctors may recommend surgery to remove all pelvic organs (pelvic exenteration). This procedure cures up to 50% of women.

Extensive Spread or Recurrence: Chemotherapy, usually with cisplatin and topotecan, is sometimes recommended. However, chemotherapy reduces the cancer’s size and controls its spread in only 15 to 25% of women treated, and this effect is usually only temporary.

Vulvar Cancer

Vulvar cancer, usually a skin cancer, develops in the area around the female genital organs.

The cancer may appear to be a lump, an itchy area, or a sore that does not heal.

The cancer may appear to be a lump, an itchy area, or a sore that does not heal.

A sample of the abnormal tissue is removed and examined (biopsied).

A sample of the abnormal tissue is removed and examined (biopsied).

All or part of the vulva and any other affected areas are removed surgically.

All or part of the vulva and any other affected areas are removed surgically.

Reconstructive surgery can help improve appearance and function.

Reconstructive surgery can help improve appearance and function.

The vulva refers to the area that contains the external female reproductive organs. In the United States, cancer of the vulva (vulvar carcinoma) is the fourth most common gynecologic cancer, accounting for 3 to 4% of these cancers. Vulvar cancer usually occurs after menopause. The average age at diagnosis is 70 years. As more women live longer, this cancer is likely to become more common.

The risk of developing vulvar cancer is increased by the following:

Older age

Older age

Precancerous changes (dysplasia) in vulvar tissues

Precancerous changes (dysplasia) in vulvar tissues

Lichen sclerosus, which causes persistent itching and scarring of the vulva

Lichen sclerosus, which causes persistent itching and scarring of the vulva

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection

Cancer of the vagina or cervix

Cancer of the vagina or cervix

Heavy cigarette smoking

Heavy cigarette smoking

Chronic granulomatous disease (a hereditary disease that impairs the immune system)

Chronic granulomatous disease (a hereditary disease that impairs the immune system)

Most vulvar cancers are skin cancers that develop near or at the opening of the vagina. About 90% of vulvar cancers are squamous cell carcinomas, and 5% are melanomas. The remaining 5% include adenocarcinomas, which develop from gland cells, basal cell carcinomas, and rare cancers such as Paget’s disease and cancer of Bartholin’s gland.

Vulvar cancer begins on the surface of the vulva. Most of these cancers grow slowly, remaining on the surface for years. However, some (for example, melanomas) grow quickly. Untreated, vulvar cancer can eventually invade the vagina, the urethra, or the anus and spread into lymph nodes in the area.

Symptoms

White, brown, or red patches on the vulva may be precancerous (indicating that cancer is likely to eventually develop). Vulvar cancer usually causes unusual lumps or flat, red sores that can be seen and felt and that do not heal. Sometimes the flat sores become scaly, discolored, or both. The surrounding tissue may contract and pucker. Melanomas may be bluish black or brown and raised. Some sores look like warts. Typically, vulvar cancer causes little discomfort, but itching is common. Eventually, the lump or sore may bleed or produce a watery discharge (weep). These symptoms should be evaluated promptly by a doctor.

About one fifth of women have no symptoms, at least at first.

Diagnosis

Doctors diagnose vulvar cancer by taking a sample of the abnormal skin and examining it (biopsy). The biopsy enables doctors to determine whether the abnormal skin is cancerous or just infected or irritated. The type of cancer, if present, can also be identified, helping doctors develop a treatment plan. If the skin abnormalities are not well-defined, doctors apply stains to the abnormal area to help determine where to take a sample of tissue for a biopsy. Alternatively, they may use instrument with a binocular magnifying lens (colposcope) to examine the surface of the vulva.

Prognosis

If vulvar cancer is detected and treated early, about 3 of 4 women have no sign of cancer 5 years after diagnosis. The percentage of women who are alive 5 years after diagnosis and treatment depends on whether the cancer has reached the lymph nodes. If it has not, 96% are still alive. If it has, only 66% are still alive.

Melanomas are more likely to spread than squamous cell carcinomas.

Treatment

Depending on the extent and type of the cancer, all or part of the vulva is surgically removed (a procedure called vulvectomy). Nearby lymph nodes are also removed. For early-stage cancers, such treatment is usually all that is needed.

For more advanced cancers, radiation therapy, often with chemotherapy (with cisplatin or fluorouracil), may be used before vulvectomy. Such treatment can shrink very large cancers, making them easier to remove. Sometimes the clitoris and other organs in the pelvis must be removed.

After the cancer is removed, surgery to reconstruct the vulva and other affected areas (such as the vagina) may be done. Such surgery can improve function and appearance.

Doctors work closely with the woman to develop a treatment plan that is best suited to her and takes into account her age, sexual lifestyle, and any other medical problems. Sexual intercourse is usually possible after vulvectomy.

Because basal cell carcinoma of the vulva does not tend to spread (metastasize) to distant sites, surgery usually involves removing only the cancer. The whole vulva is removed only if the cancer is extensive.

Vaginal Cancer

Cancer of the vagina, an uncommon cancer, is usually a squamous cell skin cancer (vaginal carcinoma), which typically develops in older women.

Vaginal cancer may cause abnormal vaginal bleeding, particularly after sexual intercourse.

Vaginal cancer may cause abnormal vaginal bleeding, particularly after sexual intercourse.

If doctors suspect cancer, they remove and examine samples of tissue from the vagina (biopsy).

If doctors suspect cancer, they remove and examine samples of tissue from the vagina (biopsy).

The cancer is surgically removed, or radiation therapy is used.

The cancer is surgically removed, or radiation therapy is used.

In the United States, vaginal cancer accounts for only about 1% of gynecologic cancers. The average age at diagnosis is 60 to 65.

More than 95% of vaginal cancers are squamous cell carcinomas. Vaginal squamous cell carcinoma may be caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), the same virus that causes genital warts and cervical cancer. Having HPV infection or cervical or vulvar cancer increases the risk of developing vaginal cancer.

Most other vaginal cancers are adenocarcinomas. One rare type, clear cell carcinoma, occurs almost exclusively in women whose mothers took the drug diethylstilbestrol (DES), prescribed to prevent miscarriage during pregnancy. (In 1971, the drug was banned in the United States.)

Depending on the type, vaginal cancer may begin on the surface of the vaginal lining. If untreated, it continues to grow and invades surrounding tissue. Eventually, it may enter blood and lymphatic vessels, then spread to other parts of the body.

Symptoms

The most common symptom is bleeding from the vagina, which may occur during or after sexual intercourse, between menstrual periods, or after menopause. Sores may form on the lining of the vagina. They may bleed and become infected. Other symptoms include a watery discharge and pain during sexual intercourse. A few women have no symptoms. Large cancers can also affect the bladder, causing a frequent urge to urinate and pain during urination. In advanced cancer, abnormal connections (fistulas) may form between the vagina and the bladder or rectum.

Diagnosis

Doctors may suspect vaginal cancer based on symptoms, abnormal areas seen during a routine pelvic examination, or an abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) test result. Doctors may use an instrument with a binocular magnifying lens (colposcope) to examine the vagina. To confirm the diagnosis, doctors scrape cells from the vaginal wall to examine under a microscope. They also do a biopsy on any growth, sore, or other abnormal area seen during the examination.

Other tests, such as use of a viewing tube (endoscopy) to examine the bladder or rectum, a chest x-ray, and computed tomography (CT), may be done to determine whether the cancer has spread.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the stage of the cancer (see table on page 1571). If the cancer is limited to the vagina, about 65 to 70% of women survive at least 5 years after diagnosis. If the cancer has spread beyond the pelvis or to the bladder or rectum, only about 15 to 20% survive.

Treatment

Treatment also depends on the stage. For early-stage vaginal cancers, surgery to remove the vagina, uterus, and lymph nodes in the pelvis and the upper part of the vagina is the treatment of choice. Radiation therapy is used for most other cancers. It is usually a combination of internal (using radioactive implants placed inside the vagina) and external (directed at the pelvis from outside the body) radiation therapy.

Radiation therapy cannot be used if fistulas have developed. In such cases, the organs in the pelvis are removed.

Intercourse may be difficult or impossible after treatment for vaginal cancer, although sometimes a new vagina can be constructed with skin grafts or part of the intestine.

Fallopian Tube Cancer

Fallopian tube cancer develops in the tubes that lead from the ovaries to the uterus.

Most cancers that affect the fallopian tubes have spread from other parts of the body.

Most cancers that affect the fallopian tubes have spread from other parts of the body.

At first, women may have vague symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort or bloating, or no symptoms.

At first, women may have vague symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort or bloating, or no symptoms.

Ultrasonography or computed tomography is done to check for abnormalities.

Ultrasonography or computed tomography is done to check for abnormalities.

Usually, the uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes are removed, followed by chemotherapy.

Usually, the uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes are removed, followed by chemotherapy.

In the United States, fewer than 1% of gynecologic cancers are fallopian tube cancers. Most often, cancer that affects the fallopian tubes has spread from the ovaries rather than started in the fallopian tubes. Cancer that starts in the fallopian tubes usually affects women aged 50 to 60. It is more likely to develop in women who have had the following:

Long-term inflammation of the fallopian tubes (chronic salpingitis)

Long-term inflammation of the fallopian tubes (chronic salpingitis)

Disorders that cause inflammation in other parts of the body, such as tuberculosis

Disorders that cause inflammation in other parts of the body, such as tuberculosis

Infertility

Infertility

More than 95% of fallopian tube cancers are adenocarcinomas, which develop from gland cells. A few are sarcomas, which develop from connective tissue. Fallopian tube cancer spreads in much the same way as ovarian cancer: usually directly to the surrounding area or through the lymphatic system, eventually appearing in distant parts of the body.

Symptoms

Symptoms include vague abdominal discomfort, bloating, and pain in the pelvic area or abdomen. Some women have a watery or blood-tinged discharge from the vagina. When cancer is advanced, the abdominal cavity may fill with fluid (a condition called ascites), and women may feel a large mass in the pelvis.

Diagnosis

Fallopian tube cancer is seldom diagnosed early. Occasionally, it is diagnosed early when a mass or other abnormality is detected during a routine pelvic examination or an imaging test done for another reason. Usually, the cancer is not diagnosed until it is advanced, when it is obvious because a large mass or severe ascites is present.

If cancer is suspected, computed tomography (CT) is usually done. If the results suggest cancer, surgery is done to confirm the diagnosis, determine the extent of spread, and remove as much of the cancer as possible.

Prognosis and Treatment

The prognosis is similar to that for women who have ovarian cancer.

Treatment almost always consists of removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) and removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes (salpingo-oophorectomy), adjacent lymph nodes, and surrounding tissues. Chemotherapy (as for ovarian cancer) is usually necessary after surgery. The most commonly used chemotherapy drugs are carboplatin and paclitaxel.

For some cancers, radiation therapy is useful. For cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, removing as much of the cancer as possible improves the prognosis.

Hydatidiform Mole

A hydatidiform mole is growth of an abnormal fertilized egg or an overgrowth of tissue from the placenta.

Women appear to be pregnant, but the uterus enlarges much more rapidly than in a normal pregnancy.

Women appear to be pregnant, but the uterus enlarges much more rapidly than in a normal pregnancy.

Most women have severe nausea and vomiting, vaginal bleeding, and very high blood pressure.

Most women have severe nausea and vomiting, vaginal bleeding, and very high blood pressure.

Ultrasonography, blood tests to measure human chorionic gonadotropin (which is produced early during pregnancy) and a biopsy are done.

Ultrasonography, blood tests to measure human chorionic gonadotropin (which is produced early during pregnancy) and a biopsy are done.

Moles are removed using dilation and curettage with suction.

Moles are removed using dilation and curettage with suction.

If the disorder persists, chemotherapy is needed.

If the disorder persists, chemotherapy is needed.

Most often, a hydatidiform mole is an abnormal fertilized egg that develops into a hydatidiform mole rather than a fetus (a condition called molar pregnancy). However, a hydatidiform mole can develop from cells that remain in the uterus after a miscarriage or a full-term pregnancy. Rarely, a hydatidiform mole develops when there is a living fetus. In such cases, the fetus typically dies, and a miscarriage often occurs.

Hydatidiform moles are most common among women under 17 or over 35. In the United States, they occur in about 1 in 2,000 pregnancies in the United States. For unknown reasons, moles are almost 10 times more common in Asian countries.

About 80% of hydatidiform moles are not cancerous. About 15 to 20% invade the surrounding tissue and tend to persist. About 2 to 3% become cancerous and spread throughout the body. They are then called choriocarcinomas. Choriocarcinomas can spread quickly through the lymphatic vessels or bloodstream. Hydatidiform moles and choriocarcinomas are types of gestational trophoblastic disease.

Symptoms

Women who have a hydatidiform mole feel as if they are pregnant. But because hydatidiform moles grow much faster than a fetus, the abdomen becomes larger much faster than it does in a normal pregnancy. Severe nausea and vomiting are common, and vaginal bleeding may occur. As parts of the mole deteriorate, small amounts of tissue, which resemble a bunch of grapes, may pass through the vagina. These symptoms indicate the need for prompt evaluation by a doctor.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

An abnormal fertilized egg or placental tissue can overgrow, causing symptoms similar to those of pregnancy, but the abdomen enlarges more rapidly.

Hydatidiform moles can cause serious complications, including infections and very high blood pressure with increased protein in the urine (pre-eclampsia or eclampsia—see page 1649).

If choriocarcinoma develops, women may have other symptoms, caused by spread (metastasis) to other parts of the body.

Diagnosis

Often, doctors can diagnose a hydatidiform mole shortly after conception. The pregnancy test is positive, but no fetal movement and no fetal heartbeat are detected, and the uterus is much larger than expected.

Ultrasonography is done to be sure that the growth is a hydatidiform mole and not a fetus or amniotic sac (which contains the fetus and fluid around it). Blood tests to measure the level of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG—a hormone normally produced early in pregnancy) are done. If a hydatidiform mole is present, the level is usually very high because the mole produces a large amount of this hormone. A sample of tissue is removed or obtained when it is passed, then examined under a microscope (biopsy) to confirm the diagnosis.

Prognosis

The cure rate for a hydatidiform mole is virtually 100% if the mole has not spread. The cure rate is 60 to 80% for choriocarcinoma that has spread widely. Most women can have children afterwards and do not have a higher risk of having complications, a miscarriage, or children with birth defects.

About 1% of women who have had a hydatidiform mole have another one. So if women have had a hydatidiform mole, ultrasonography is done early in subsequent pregnancies.

Treatment

A hydatidiform mole is completely removed, usually by dilation and curettage (D and C) with suction (see page 1504). Only rarely is removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) necessary.

A chest x-ray is done to see whether the mole has become cancerous (that is, a choriocarcinoma) and spread to the lungs. After surgery, the level of human chorionic gonadotropin in the blood is measured to determine whether the hydatidiform mole was completely removed. When removal is complete, the level returns to normal, usually within 10 weeks, and remains normal. If the level does not return to normal (called persistent disease), computed tomography (CT) of the brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvis is done to determine whether choriocarcinoma has developed and spread.

Hydatidiform moles do not require chemotherapy, but persistent disease does. Usually, only one drug (methotrexate or dactinomycin) is needed. Sometimes both drugs or another combination of chemotherapy drugs is needed.

Women who have had a hydatidiform mole removed are advised not to become pregnant for 1 year. Oral contraceptives are frequently recommended, but other effective contraceptive methods can be used.