CHAPTER 257

Normal Labor and Delivery

Although each labor and delivery is different, most follow a general pattern. Therefore, an expectant mother can have a general idea of what changes will occur in her body to enable her to deliver the baby and what procedures will be followed to help her. She also has several choices to make, such as whether to have a support person (such as the baby’s father or another partner) present and where to have the baby.

An expectant mother may want her partner to remain with her during labor. The partner’s encouragement and emotional support may help her relax, sometimes reducing her need for drugs to relieve pain. In addition, sharing the meaningful experience of childbirth has emotional and psychologic benefits, such as creating strong family bonds. On the other hand, an expectant mother may prefer privacy during labor, or the partner may not want to be present. Childbirth education classes prepare both mother and partner for the entire process.

In the United States, almost all babies are born in hospitals, but some women want to have their babies at home. However, unexpected complications can occur during or shortly after labor, even in women who had good prenatal care and no signs of any problems. Thus, most experts do not advise delivery at home. Women who prefer a homelike setting and fewer rules (for example, no limit on the number of visitors or on visiting hours) may choose birthing centers. Such centers provide an informal, personal experience of childbirth but are much safer than delivery at home. Birthing centers are part of a hospital or have an arrangement with a nearby hospital. Thus, birthing centers can provide a medical staff, emergency equipment, and full hospital facilities, if needed. If complications develop during labor, birthing centers immediately transfer the woman to the hospital.

Some hospitals have private rooms in which a woman stays from labor until discharge. These rooms are called LDRPs for labor, delivery, recovery, and postpartum (after delivery).

Regardless of the choices a woman makes, knowing what to expect helps prepare her for labor and delivery.

Labor

Labor is a series of rhythmic, progressive contractions of the uterus that gradually move the fetus through the lower part of the uterus (cervix) and birth canal (vagina) to the outside world.

Labor occurs in three main stages:

First stage: This stage (which has two phases: initial and active) is labor proper. Contractions cause the cervix to open gradually (dilate) and to thin and pull back (efface) until it merges with the rest of the uterus. These changes enable the fetus to pass through the vagina.

First stage: This stage (which has two phases: initial and active) is labor proper. Contractions cause the cervix to open gradually (dilate) and to thin and pull back (efface) until it merges with the rest of the uterus. These changes enable the fetus to pass through the vagina.

Second stage: The baby is delivered.

Second stage: The baby is delivered.

Third stage: The placenta is delivered.

Third stage: The placenta is delivered.

Labor usually starts within 2 weeks of (before or after) the estimated date of delivery. Exactly what causes labor to start is unknown. Toward the end of pregnancy (after 36 weeks), a doctor examines the cervix to try to predict when labor will start. On average, labor lasts 12 to 18 hours in a woman’s first pregnancy and tends to be shorter, averaging 6 to 8 hours, in subsequent pregnancies.

Start of Labor

All pregnant women should know what the main signs of the start of labor are:

Contractions in the lower abdomen at regular intervals

Contractions in the lower abdomen at regular intervals

Back pain

Back pain

A woman who has had rapid deliveries in previous pregnancies should notify her doctor as soon as she thinks she is going into labor. When contractions in the lower abdomen first start, they may be weak, irregular, and far apart. They may feel like menstrual cramps. As time passes, abdominal contractions become longer, stronger, and closer together. Contractions and back pain may be preceded or accompanied by other clues, such as the following:

Bloody show: A small discharge of blood mixed with mucus from the vagina is usually a clue that labor is about to start. The bloody show may appear as early as 72 hours before contractions start.

Bloody show: A small discharge of blood mixed with mucus from the vagina is usually a clue that labor is about to start. The bloody show may appear as early as 72 hours before contractions start.

Rupture of membranes: Occasionally, the fluid-filled membranes that contain the fetus (amniotic sac) rupture before labor starts, and the amniotic fluid flows out through the vagina. This event is commonly described as “the water breaks.”

Rupture of membranes: Occasionally, the fluid-filled membranes that contain the fetus (amniotic sac) rupture before labor starts, and the amniotic fluid flows out through the vagina. This event is commonly described as “the water breaks.”

When a woman’s membranes rupture, she should contact her doctor or midwife immediately. About 80 to 90% of women whose membranes rupture before but near their due date go into labor spontaneously within 24 hours. If labor has not started after several hours and the baby is due, women are usually admitted to the hospital, where labor is artificially started (induced) to reduce the risk of infection. After the membranes rupture, bacteria from the vagina can enter the uterus more easily and cause an infection in the woman, the fetus, or both. Oxytocin (which causes the uterus to contract) or a similar drug, such as a prostaglandin, is used to induce labor. If the membranes rupture more than 3 weeks before the due date (prematurely), doctors do not induce labor until the fetus is more mature (see page 1657).

Admission to a Hospital or Birthing Center

When the membranes rupture or when strong contractions occur less than 6 minutes apart or last 30 seconds or more, a woman should go to a hospital or birthing center. If rupture of membranes is suspected or the cervix is dilated more than 1 ½ inches (4 centimeters), the woman is admitted. The strength, duration, and frequency of contractions are noted. Her weight, blood pressure, heart and breathing rates, and temperature are measured, and samples of urine and blood are taken for analysis. Her abdomen is examined to estimate how big the fetus is, whether the fetus is facing rearward or forward (position), and whether the head, face, buttocks, or shoulder is leading the way out (presentation).

Position and presentation of the fetus affect how the fetus passes through the vagina. The most common and safest combination consists of the following:

Head first

Head first

Facing rearward (facing down when the woman lies on her back)

Facing rearward (facing down when the woman lies on her back)

Face and body angled toward the right or left

Face and body angled toward the right or left

Neck bent forward

Neck bent forward

Chin tucked in

Chin tucked in

Arms folded across the chest (see art on page 1660)

Arms folded across the chest (see art on page 1660)

Head first is called a vertex or cephalic presentation. During the last week or two before delivery, most fetuses turn so that the back of the head presents first. If the presentation is buttocks first (breech) or shoulder first or the fetus is facing forward, delivery is considerably more difficult for the woman, fetus, and doctor. Cesarean delivery is recommended.

Stages of Labor

FIRST STAGE

From the beginning of labor to the full opening (dilation) of the cervix—to about 4 inches (10 centimeters).

Initial (Latent) Phase

Contractions become progressively stronger and more rhythmic.

Discomfort is minimal.

The cervix begins to thin and opens to about 1 ½ inches (4 centimeters).

This phase lasts an average of 8 ½ hours (up to 20 hours) in a first pregnancy and 5 hours (up to 12 hours) in subsequent pregnancies.

Active Phase

The cervix opens from about 1 ½ inches (4 centimeters) to the full 4 inches (10 centimeters). It thins and pulls back (effaces) until it merges with the rest of the uterus.

The presenting part of the baby, usually the head, begins to descend into the woman’s pelvis.

The woman begins to feel the urge to push as the baby descends, but she should resist it.

This phase averages about 5 to 7 hours in a first pregnancy and 2 to 4 hours in subsequent pregnancies.

SECOND STAGE

From the complete opening of the cervix to delivery of the baby: This stage averages about 45 to 60 minutes in a first pregnancy and 15 to 30 minutes in subsequent pregnancies. During this stage, the woman pushes.

THIRD STAGE

From delivery of the baby to delivery of the placenta: This stage usually lasts only a few minutes but may last up to 30 minutes.

Monitoring the Fetus

Electronic monitoring is used to continuously monitor the fetus’s heart rate and the contractions of the uterus. It is used for virtually all high-risk pregnancies and, in many practices, for all pregnancies. Certain changes in the fetus’s heart rate during contractions can indicate that the fetus is not receiving enough oxygen.

The fetus’s heart rate can be monitored in the following ways:

Externally: An ultrasound device (which transmits and receives ultrasound waves) is attached to the woman’s abdomen.

Externally: An ultrasound device (which transmits and receives ultrasound waves) is attached to the woman’s abdomen.

Internally: An electrode is inserted through the woman’s vagina and attached to the fetus’s scalp. The internal approach is typically used only when problems during labor appear likely or when signals detected by the external device cannot be recorded.

Internally: An electrode is inserted through the woman’s vagina and attached to the fetus’s scalp. The internal approach is typically used only when problems during labor appear likely or when signals detected by the external device cannot be recorded.

In a high-risk pregnancy, electronic monitoring is sometimes used as part of a nonstress test, in which the fetus’s heart rate is monitored as the fetus lies still and as it moves. If the heart rate does not increase with movement (is nonreactive), an ultrasound biophysical profile or a contraction stress test may be done. These tests check on the fetus’s well-being.

For an ultrasound biophysical profile, ultrasonography is used to produce images of the fetus in real time, and the following are assigned a score of 0 or 2 within a 30-minute period of observation:

Amount of amniotic fluid

Amount of amniotic fluid

Presence or absence of a period of breathing

Presence or absence of a period of breathing

Presence or absence of at least 3 clearly visible movements of the fetus

Presence or absence of at least 3 clearly visible movements of the fetus

Muscle tone of the fetus, indicated by certain back and forth changes in position of fingers, a limb, or the trunk

Muscle tone of the fetus, indicated by certain back and forth changes in position of fingers, a limb, or the trunk

A score of up to 8 is possible.

For a contraction stress test, oxytocin (a hormone that causes the uterus to contract during labor) is usually given intravenously to start uterine contractions. The fetus’s heart rate is monitored during these contractions to determine whether the fetus will be able to withstand labor. If the fetus’s heart rate decreases as contractions peak, the contractions may deprive the fetus of oxygen and the fetus may be injured.

On the basis of such tests, a doctor may allow labor to continue or may do a cesarean delivery immediately.

A vaginal examination is done to determine whether the membranes have ruptured and how dilated and effaced the cervix is, but this examination may be omitted if the woman is bleeding or if the membranes have ruptured spontaneously. The color of the amniotic fluid is noted. The fluid should be clear and have no significant odor. If the membranes rupture and the amniotic fluid is green, the discoloration results from the fetus’s first stool (fetal meconium).

An intravenous line is usually inserted into the woman’s arm during labor in a hospital. This line is used to give the woman fluids to prevent dehydration and, if needed, to give drugs.

When fluids are given intravenously, the woman does not have to eat or drink during labor, although she may choose to drink some fluids and eat some light food early in labor. An empty stomach during delivery makes the woman less likely to vomit. Very rarely, vomit is inhaled. Inhaling vomit can cause inflammation of the lungs, which can be life threatening. Usually, the woman is given an antacid by mouth to neutralize stomach acid when she is admitted to the hospital and every 3 hours after that. Antacids reduce the risk of damage to the lungs if vomit is inhaled.

Fetal Monitoring

Soon after the woman is admitted to the hospital, the doctor or another health care practitioner listens to the fetus’s heartbeat periodically using a handheld Doppler ultrasound device, or electronic fetal heart monitoring is used to continuously monitor heartbeats.

During the first stage of labor, the heart rates of the woman and fetus are monitored periodically or continuously. Monitoring the fetus’s heart rate is the easiest way to determine whether the fetus is receiving enough oxygen. An abnormal heart rate (too fast or too slow) may indicate that the fetus is in distress (see page 1659). During the second stage of labor, the woman’s heart rate and blood pressure are monitored regularly. The fetus’s heart rate is monitored after every contraction or, if electronic monitoring is used, continuously.

Pain Relief

With the advice of her doctor or midwife, a woman usually plans an approach to pain relief long before labor starts. She may choose natural childbirth, which relies on relaxation and breathing techniques to deal with pain, or she may plan to use analgesics (given intravenously) or a particular type of anesthetic (local or regional) if needed. After labor starts, these plans may be modified, depending on how labor progresses, how the woman feels, and what the doctor or midwife recommends.

A woman’s need for pain relief during labor varies considerably, depending to some extent on her level of anxiety. Attending childbirth preparation classes helps prepare the woman for labor and delivery. Such preparation and emotional support from the people attending the labor tend to lessen anxiety and often markedly reduce her need for drugs to relieve pain.

Analgesics may be used. If a woman requests analgesics during labor, they are usually given to her. However, because some of these drugs can slow (depress) breathing and other functions of the newborn, the amount given is as small as possible. Most commonly, fentanyl or morphine is given intravenously to relieve pain. These drugs may slow the initial phase of the first stage of labor, so they are usually given during the active phase of the first stage. In addition, because these drugs have the greatest effect during the first 30 minutes after they are given, the drugs are often not given when delivery is imminent. If they are given too close to delivery, the newborn may be overly sedated, making adjustment to life outside the uterus more difficult. To counteract the sedating effects of these drugs on the newborn, a doctor can give the newborn the drug naloxone immediately after delivery.

Local anesthesia numbs the vagina and the tissues around its opening. Commonly, this area is numbed by injecting a local anesthetic through the wall of the vagina into the area around the nerve that supplies sensation to the lower genital area (pudendal nerve). This procedure, called a pudendal block, is used only late in the second stage of labor, when the baby’s head is about to emerge from the vagina. Another common but less effective procedure involves injecting a local anesthetic at the opening of the vagina. With both procedures, the woman can remain awake and push, and the fetus’s functions are unaffected. These procedures are useful for deliveries that have no complications.

Regional anesthesia numbs a larger area. It may be used for women who want more complete pain relief. The following procedures can be used:

Lumbar epidural injection is almost always used. It is used much more often than pudendal blocks. An anesthetic is injected in the lower back—into the space between the spine and the outer layer of tissue covering the spinal cord (epidural space). Alternatively, a catheter is placed in the epidural space, and an opioid, such as fentanyl or sufentanil, is continuously and slowly given through the catheter. A lumbar epidural injection for labor and delivery does not prevent the woman from pushing adequately.

Lumbar epidural injection is almost always used. It is used much more often than pudendal blocks. An anesthetic is injected in the lower back—into the space between the spine and the outer layer of tissue covering the spinal cord (epidural space). Alternatively, a catheter is placed in the epidural space, and an opioid, such as fentanyl or sufentanil, is continuously and slowly given through the catheter. A lumbar epidural injection for labor and delivery does not prevent the woman from pushing adequately.

Spinal injection involves injecting an anesthetic into the space between the middle and inner layers of tissue covering the spinal cord (subarachnoid space). A spinal injection is typically used for cesarean delivery when there are no complications.

Spinal injection involves injecting an anesthetic into the space between the middle and inner layers of tissue covering the spinal cord (subarachnoid space). A spinal injection is typically used for cesarean delivery when there are no complications.

Natural Childbirth

Natural childbirth uses relaxation and breathing techniques to control pain during childbirth. Natural childbirth often helps reduce or eliminate the need for analgesics or anesthetics during labor and delivery.

To prepare for natural childbirth, a pregnant woman and her partner take childbirth classes, usually six to eight sessions over several weeks, to learn how to use the relaxation and breathing techniques. They also learn what happens in the various stages of labor and delivery.

The relaxation technique involves consciously tensing a part of the body and then relaxing it. This technique helps a woman relax the rest of her body while the uterus is contracting during labor and relax her whole body between contractions.

The breathing technique involves several types of breathing, which are used at different times during labor. During the first stage of labor, before the woman begins to push, the following types of breathing may help:

Deep breathing with slow exhalation to help the woman relax at the beginning and end of a contraction

Deep breathing with slow exhalation to help the woman relax at the beginning and end of a contraction

Fast, shallow breathing (panting) in the upper chest at the peak of a contraction

Fast, shallow breathing (panting) in the upper chest at the peak of a contraction

A pattern of panting and blowing to help the woman refrain from pushing when she has an urge to push before the cervix is completely dilated

A pattern of panting and blowing to help the woman refrain from pushing when she has an urge to push before the cervix is completely dilated

In the second stage of labor, the woman alternates between pushing and panting.

The woman and her partner should practice relaxation and breathing techniques regularly during pregnancy. During labor, the woman’s partner can help her by reminding her of what she should be doing at a particular stage and by noticing when she is tense, in addition to providing emotional support. The partner may massage the woman to help her relax more.

The most well-known method of natural childbirth is probably the Lamaze method. Another method, the Leboyer method, includes birth in a darkened room and immersion of the baby into lukewarm water immediately after delivery.

Occasionally, use of either an epidural or a spinal injection causes a fall in blood pressure. Consequently, if one of these procedures is used, the woman’s blood pressure is measured frequently.

General anesthesia makes a woman temporarily unconscious. It is rarely necessary and infrequently used because it may slow the function of the fetus’s heart, lungs, and brain. Although this effect is usually temporary, it can interfere with the newborn’s adjustment to life outside the uterus. General anesthesia is typically used for emergency cesarean delivery because it is the quickest way to anesthetize the woman.

Delivery

Delivery is the passage of the fetus and placenta (afterbirth) from the uterus to the outside world.

For delivery in a hospital, a woman may be moved from a labor room to a birthing or delivery room, a room used only for deliveries. Usually, the father, partner, or other support people are encouraged to accompany her. If she is already in an LDRP (for labor, delivery, recovery, and postpartum), she remains there. The intravenous line remains in place.

When a woman is about to give birth, she may be placed in a semi-upright position, between lying down and sitting up. Her back can be supported by pillows or a backrest. The semi-upright position uses gravity: The downward pressure of the fetus helps the vagina and surrounding area stretch gradually, decreasing the risk of tearing. This position also puts less strain on the woman’s back and pelvis. Some women prefer to deliver lying down. However, with this position, delivery may take longer.

Delivery of the Baby

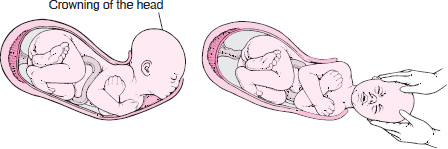

As delivery progresses, the doctor or midwife examines the vagina to determine the position of the fetus’s head. When the cervix is fully open (dilated) and thinned and pulled back (effaced), the woman is asked to bear down and push with each contraction to help move the fetus’s head down through her pelvis and to widen the vaginal opening so that more and more of the head appears. When more than 1 inch (3 to 4 centimeters) of the head appears, the doctor or midwife places a hand over the fetus’s head during a contraction to control the fetus’s progress. As the head crowns (when the widest part of the head passes through the vaginal opening), the head and chin are eased out of the vaginal opening to prevent the woman’s tissues from tearing.

Vacuum extraction can be used to assist in delivery of the head when the fetus is in distress or the woman is having difficulty pushing (see page 1664).

Forceps are sometimes used for the same reasons but are used less often than vacuum extractors.

Episiotomy is an incision that widens the opening of the vagina to make delivery of a baby easier. It is no longer done routinely. It is used only when necessary for immediate delivery. For this procedure, the doctor injects a local anesthetic to numb the area and makes an incision in the area between the openings of the vagina and anus (called the perineum). If the muscle around the opening of the anus (rectal sphincter) is damaged during an episiotomy or is torn during delivery, it usually heals well if the doctor repairs it immediately.

After the baby’s head has emerged, the body is rotated sideways so that the shoulders can emerge easily, one at a time. The rest of the baby usually slips out quickly after the first shoulder comes out. Mucus and fluid are suctioned out of the baby’s nose, mouth, and throat. The umbilical cord is clamped and cut. The baby is then dried, wrapped in a lightweight blanket, and placed on the woman’s abdomen or in a warmed bassinet.

Delivery of the Placenta

After delivery of the baby, the doctor or midwife places a hand gently on the woman’s abdomen to make sure the uterus is contracting. After delivery, the placenta usually detaches from the uterus within 3 to 10 minutes, and a gush of blood soon follows. Usually, the woman can push the placenta out on her own. If she cannot and particularly if she is bleeding excessively, the doctor or midwife applies firm downward pressure on the woman’s abdomen, causing the placenta to detach from the uterus and come out. If the placenta has not been delivered within 45 to 60 minutes of delivery, the doctor or midwife may insert a hand into the uterus, separating the placenta from the uterus and removing it.

After the placenta is removed, it is examined for completeness. Fragments left in the uterus prevent the uterus from contracting. Contractions are essential to prevent further bleeding from the area where the placenta was attached to the uterus. So if fragments remain, bleeding can occur after delivery and may be substantial. Infections can also occur. If the placenta is incomplete, the doctor or midwife may remove the remaining fragments by hand. Sometimes fragments have to be surgically removed.

In many hospitals, as soon as the placenta is delivered or removed, the woman is given oxytocin (intravenously or intramuscularly), and her abdomen is periodically massaged to help the uterus contract.

After Delivery

The doctor stitches up any tears in the cervix, vagina, or nearby muscles and tissues and, if an episiotomy was done, the episiotomy incision. The woman is then moved to the recovery room or remains in the LDRP. Often, a baby who does not need further medical attention stays with the mother. Typically, the woman and her baby remain together in a warm, private area for 3 to 4 hours so that bonding can begin. Many women wish to begin breastfeeding soon after delivery. Later, the baby may be taken to the hospital nursery. In many hospitals, the woman may choose to have the baby remain with her—a practice called rooming-in. All hospitals with LDRPs require it. With rooming-in, the baby is usually fed on demand, and the woman is taught how to care for the baby before she leaves the hospital. If a woman needs a rest, she may have the baby taken to the nursery.

Because most complications, particularly bleeding, occur within the first 24 hours after delivery, nurses and doctors carefully observe the woman and baby during this time.