CHAPTER 301

Fractures

A fracture is a crack or break in a bone, usually accompanied by injury to the surrounding tissues.

Fractures cause pain and swelling.

Fractures cause pain and swelling.

Complications may involve damage to nerves, blood vessels, muscles, and internal organs and can be serious.

Complications may involve damage to nerves, blood vessels, muscles, and internal organs and can be serious.

Most fractures are diagnosed by x-rays, although some require repeat x-rays in 7 to 10 days or computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.

Most fractures are diagnosed by x-rays, although some require repeat x-rays in 7 to 10 days or computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.

Treatments range from mild restrictions on activity to casts or surgery.

Treatments range from mild restrictions on activity to casts or surgery.

Rehabilitation is often helpful to build up strength and range of motion of the affected body part.

Rehabilitation is often helpful to build up strength and range of motion of the affected body part.

Fractures vary greatly in size, severity, and the treatment needed. They can range from a small, easily missed crack in a foot bone to a massive, life-threatening break of the pelvis. Serious injuries, including injuries to the skin, nerves, blood vessels, muscles, and organs, may occur at the same time as the fracture. These injuries can complicate treatment of the fracture, cause temporary or permanent problems, or both.

Trauma is the most common cause of fractures. Low-energy trauma, such as a fall on level ground, usually causes minor fractures. High-energy trauma, such as high-speed motor vehicle collisions and falls from buildings, can cause severe fractures that involve several bones.

Certain underlying disorders can weaken parts of the skeleton so that breaks are more likely to occur. Such disorders include certain infections, benign bone tumors, cancer, and osteoporosis.

Symptoms

Pain is the most obvious symptom. Fractures hurt, especially when force is applied, such as when a person tries to put weight on an injured limb. The area around the broken bone is also tender to touch. Swelling of soft tissue around the fracture begins within a few hours. The limb may not function properly, so that an arm or a leg, hand, finger, or toe may move in only a limited range or in an abnormal direction. Moving is very painful. For a person who cannot speak (for example, a very young child, a person with a head injury, or an older person with dementia), refusal to move an extremity may be the only sign of a fracture. However, some fractures do not keep people from moving an injured extremity. Just because an extremity can move does not mean there is no fracture.

Complications

Internal bleeding may occur with a closed fracture (one in which the skin is not torn). The bleeding may occur from the bone itself or from surrounding soft tissues. The blood eventually works its way to the surface, forming a bruise (ecchymosis). At first, the bruise is purplish black, but it then slowly turns to green and yellow as the blood is broken down and reabsorbed back into the body. The blood can move quite a distance from the fracture, and it can take a few weeks for blood to be reabsorbed. The blood can cause temporary pain and stiffness in surrounding structures. Shoulder fractures, for instance, can bruise the entire arm and cause pain in the elbow and wrist. Some fractures, especially pelvic and femur fractures, can cause a person to lose quite a lot of blood into the surrounding tissues, resulting in low blood pressure.

Injury to an artery, vein, or nerve may occur. An open fracture (in which the skin is torn) can lead to a bone infection (osteomyelitis), which may be very difficult to cure. Fractures of long bones may release enough fat (and other substances in bone marrow) to travel through the veins, lodge in the lungs, and block a blood vessel there. Respiratory complications can result. Fractures that extend into joints usually damage cartilage (a smooth, tough, protective tissue that reduces friction as joints move). Damaged cartilage tends to scar, causing osteoarthritis and impairing motion in the joints.

How Bones Heal

When most tissues, such as those of the skin, muscles, and internal organs, become injured, they tend to mend by having scar tissue replace the healthy tissue. The scar tissue often compromises the tissue’s appearance or function in some way. In contrast, bone is unique in that it heals with its own tissue— bone—rather than with scar tissue. New bone made by the body to repair a fracture is called callus, and its formation and progress can be seen on x-rays. This unusual capacity for regeneration enables a mending bone to heal itself after a fracture, often so that the fracture eventually becomes virtually undetectable. Even shattered fragments of bone, with proper treatment, can often be restored to their normal function.

Fractures heal in three overlapping phases: inflammation, repair, and remodeling. Healing begins immediately with the inflammatory phase. In this phase, damaged soft tissue, bone fragments, and lost blood caused by the injury are removed by cells of the immune system. The region around the fracture becomes swollen and tender as cell activity and blood flow increase. The inflammatory phase reaches peak activity in a couple of days, but it takes weeks to subside. This process accounts for most of the early pain people experience with fractures.

The repair phase begins within days of the injury and lasts for weeks to months. New repaired bone, called the external callus, is formed during this phase. When first produced, the callus has no calcium. It is soft and rubbery and cannot be seen on an x-ray. This new bone is neither strong nor stable, so that during this period the fractured bone can easily collapse and become displaced (that is, slip out of its proper place). After 3 to 6 weeks, the callus calcifies and becomes much stiffer and stronger and becomes visible on x-rays.

The remodeling phase (in which the bone is built back to its normal state) lasts many months. The bulky external callus is slowly resorbed and replaced by stronger bone. During this phase, the normal contours and architecture of the bone are restored. It is not likely that the bone will fracture again during this phase. However, people may experience mild pain when pressure is applied to the bone that is rebuilding.

The person usually feels some discomfort with activities even after fractures have healed sufficiently to allow full weight bearing. For example, a fractured wrist may be strong enough to allow some use in about 2 months, but the bone is still being rebuilt (remodeled). Forceful gripping with the wrist will be painful for up to 1 year. The person may also notice increased pain and stiffness when the weather is damp, cold, or stormy.

Most fractures heal with few problems. However, some do not heal despite appropriate diagnosis and treatment. This failure to heal is called nonunion. Fractures may also heal very slowly (called delayed union) or incompletely (called malunion). Certain bones, such as the scaphoid bone of the hand and some parts of the hip, are prone to poor healing because the blood supply is often damaged when these areas are fractured.

Compartment Syndrome: Compartment syndrome is a very rare but serious limb-threatening condition caused by excessive swelling of injured muscles, such as may occur as a result of a fracture or crush injury to a limb. Certain muscle groups, such as those of the lower leg, are surrounded by a tight fibrous covering. This covering forms a closed space (compartment) that cannot expand to accommodate the normal swelling that occurs when muscles or bones inside that compartment are damaged. Instead, the swelling causes the pressure within the muscle tissue to increase. This increase in pressure decreases the blood flow that provides oxygen to the muscle. When the muscle is deprived of oxygen for too long, further injury to the muscle occurs, which leads to further swelling and higher tissue pressures. After only a few hours, irreversible injury and death of muscle and nearby soft tissues may result. A similar increase in muscle pressure and tissue damage can occur when a damaged limb is confined by a cast. Compartment syndrome is most common with fractures of the lower leg.

A doctor becomes concerned about compartment syndrome when people who have a fracture feel

Increasing pain in an immobilized limb

Increasing pain in an immobilized limb

Pain when the fingers or toes of an immobilized limb are moved gently

Pain when the fingers or toes of an immobilized limb are moved gently

Numbness in the limb

Numbness in the limb

The diagnosis of compartment syndrome can be confirmed by using a device that measures pressure in the muscles.

Pulmonary Embolism: Pulmonary embolism is the sudden blocking of blood flow in the lung when a blood clot that has formed in a vein breaks off (becoming an embolus) and travels to the lung (see page 488). Most of these clots come from the deep veins of the legs. In the lung, these clots cause many problems, including limiting blood flow to the heart, decreasing the lung’s ability to put oxygen in the blood, and damaging lung tissue. Pulmonary embolism is the most common fatal complication of serious hip and pelvic fractures. People with hip fractures are at high risk of pulmonary embolism because of the combination of trauma to the leg, forced immobilization for hours or days, and swelling around the fracture site blocking blood flow in the veins. Of people with a hip fracture who die, about one third die of pulmonary embolism. Pulmonary embolism occurs much less commonly with fractures of the lower leg and very rarely with fractures of the arm.

TYPES OF FRACTURES

| TYPE | DESCRIPTION |

| Open | The skin and soft tissue covering the bone are torn, and the bone may be seen coming out of the skin. Dirt, debris, or bacteria can easily contaminate the wound. |

| Closed | The skin is not torn. |

| Avulsion | Small fragments of bone detach from where tendons or ligaments attach to bones. These fractures usually occur in the hand, foot, ankle, knee, or shoulder. |

| Osteoporotic | Osteoporosis weakens certain areas of the skeleton, making them more likely to break. These fractures occur in older people, usually in the hips, wrists, spine, shoulders, or pelvis. |

| Compression | The bone collapses into itself. These fractures occur in older people, very commonly in the spine. |

| Joint (intraarticular) | The fracture disrupts the part of a bone that makes up one of the joint surfaces, where two different bones contact each other. Joint fractures may lead to a loss of motion and gradually developing osteoarthritis. |

| Pathologic | An underlying disorder (such as infection, a noncancerous bone tumor, or cancer) weakens a bone, leading to a fracture. |

| Stress | A bone becomes stressed repeatedly over time because of certain activities, such as walking with a heavy pack or running. Stress fractures commonly occur in bones of the foot and lower leg. |

| Occult (hairline) | These fractures are difficult or impossible for a doctor to see on an initial x-ray. They may appear as dark or white lines days to weeks after injury, often only after new bone (callus) is formed during healing. |

| Greenstick | A partial crack and a bend occur in the bone, but the bone is not completely broken through. Greenstick fractures occur only in children. |

| Growth plate | The part of the bone that allows bones to lengthen (growth plate) is broken. The bone may then stop growing or grow crookedly. Growth plate fractures occur only in children. |

| Simple transverse | The break divides a bone cleanly across. |

| Displaced | The broken ends of the bones are separated. |

| Angulated | The broken ends of the bones are bent at an angle. |

| Nondisplaced | The normal shape and alignment of a bone are maintained despite cracks completely through the bone. |

| Spiral (torsion) | The bone is twisted apart, leaving sharp, triangular bone ends. |

| Comminuted | The bone is broken into many pieces, often because of high-energy trauma or weakening by osteoporosis. |

Doctors may suspect pulmonary embolism based on a range of symptoms, including chest pain, cough, shortness of breath, extreme weakness, and fainting. An electrocardiogram (ECG), ultrasound scan, chest x-ray, or various other tests may suggest the presence of a blood clot in the lung. Confirmation usually involves computed tomography (CT) of the chest or lung scanning.

Pulmonary embolism may be prevented with drugs that reduce the tendency of the blood to clot. Such drugs include heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, and newer anticoagulants such as hirudin, danaparoid, and fondaparinux (a new drug similar to heparin). They are given to people with fractures that put them at risk of forming a pulmonary embolism. However, blood clots may form despite efforts to stop them.

Diagnosis

X-rays are the most important tool for diagnosing a fracture. X-rays are taken from several different angles to show how the fragments of bone are aligned. However, some small, nondisplaced fractures (called occult or hairline fractures) can be difficult or impossible to see on routine x-rays. Sometimes, additional x-rays taken at special angles reveal the fracture. Occasionally, such small fractures become visible on x-rays only days or weeks later, when the fracture begins to heal, revealing callus (new bone) formation. This course is particularly common with rib fractures. Stress fractures also may be undetectable on initial x-rays and visible only after callus formation begins. Fractures caused by disease (pathologic fractures) are diagnosed when x-rays show fractures in bones that have certain abnormalities, such as punched-out (lytic) areas caused by infection, noncancerous (benign) tumors, or cancer.

X-rays are usually the only test done to diagnose fractures. However, when findings strongly suggest a fracture but x-rays do not show one, doctors may do CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Alternatively, the doctor may apply a splint and re-examine the person days later and take another x-ray if symptoms are still significant. CT and MRI also are used to show details of fractures not seen on routine x-rays. CT can show the fine details of a fractured joint surface or can reveal areas of a fracture hidden by overlying bone. MRI shows the soft tissue around the bone, which helps to detect injury to nearby tendons and ligaments and joint structures, and can show evidence of cancer. MRI also shows injury (swelling or bruising) within the bone and can thus detect hidden or less visible (occult) fractures before they appear on x-rays.

Bone scanning (see page 543) is an imaging procedure that involves use of a radioactive substance (technetium-99m—labeled pyrophosphate) that is taken up by any healing bone. Occult fractures can be detected on bone scans 3 to 5 days after the injury. However, if doctors suspect an occult fracture, they usually order an MRI or CT scan rather than a bone scan.

Treatment

Fractures require immediate attention because they cause pain and loss of function. After initial emergency care, fractures usually require further treatment, such as immobilization with casts or fixation with surgery.

Fractures in children are often treated differently from those in adults because bones in children are smaller, more flexible and less brittle, and most importantly, still growing. Children’s fractures heal much faster and more perfectly than adult fractures do. Several years after most fractures in children, the bone can look almost normal on x-ray. In addition, children develop less stiffness with cast treatment and are more likely to regain normal motion if a fracture involves a joint. Because of these factors and because surgery near a joint often risks damage to the part of the bone responsible for bone growth (the growth plate), treatment with casts is often preferred over surgery.

Initial Treatment: When a fracture is suspected, people typically should go to a hospital emergency department. Those who are unable to walk or who have multiple injuries must be transported by ambulance. Until they see the doctor, people can do the following:

Immobilize and support the injured limb with a makeshift splint, sling, or a pillow

Immobilize and support the injured limb with a makeshift splint, sling, or a pillow

Elevate the limb to the level of the heart to limit swelling

Elevate the limb to the level of the heart to limit swelling

Apply ice to control pain and swelling

Apply ice to control pain and swelling

Take acetaminophen to relieve pain

Take acetaminophen to relieve pain

Aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) usually are no better than acetaminophen and in some people may worsen bleeding (see page 644).

Open fractures need to be treated immediately with surgery to carefully clean and close the wound. Massive open fractures with great losses of the skin, muscle, and blood supply to the bone are the most serious and difficult to treat.

For most closed fractures, treatment can be delayed up to 1 week without affecting the long-term result. However, there is usually no advantage to waiting, because until they are treated, people are troubled by pain and loss of function. People should keep an injured arm or leg elevated to control pain and swelling. For arm fractures, pillows are used for elevation. For leg fractures, people should lie flat with the leg on a pillow. The doctor compares the swelling of the injured limb with the normal appearance of the uninjured limb to help determine how long or often elevation is needed. During the later stages of healing, elastic stockings may be used during the daytime to help control swelling when the person is sitting or standing.

Immobilization: Fractures are immobilized with a splint, sling, or cast until they heal. Allowing the broken ends to move prevents healing and results in nonunion. Displaced fractures must be aligned (reduced) before being immobilized. Alignment without surgery is called closed reduction. Alignment with surgery is called open reduction. When minor fractures (such as those of the fingers or wrist) are reduced, people may need an injection of a local anesthetic, such as lidocaine, to prevent pain. When major fractures (such as those of the arm, shoulder, or lower leg) are reduced, people may need sedation and pain relievers given by vein, or general or spinal anesthesia.

Commonly Used Techniques for Immobilizing a Joint

A splint is a long, narrow slab of plaster, fiberglass, or aluminum applied with elastic wrap or tape. The slab does not completely encircle the limb, which allows for some expansion due to tissue swelling. For this reason, splints are often used for initial treatment of fractures. For finger fractures, aluminum splints lined with foam are commonly used.

A sling by itself provides sufficient support for many shoulder and elbow fractures. The weight of the arm pulling downward helps to keep many shoulder fractures well aligned. Cloth or a strap passing around behind the back can be added to keep the arm from swinging outward, especially at night. Slings permit some use of the hand.

A cast is made by wrapping rolls of plaster or fiberglass strips that harden once wetted. Plaster is often chosen for the initial cast when a displaced fracture is being treated. It molds well and has less of a tendency to cause painful contact points between the body and cast. Otherwise, fiberglass has the advantage of being stronger, lighter, and more durable. In either case, the cast is applied over a layer of soft cottony material to protect the skin from pressure and rubbing. If the cast becomes wet, it is often impossible to completely dry the lining. As a result, the skin can soften and break down (macerate). For partially healed fractures, a special, more expensive and less protective waterproof lining is sometimes substituted.

After a cast is applied (especially for the first 24 to 48 hours), it should be kept elevated as much as possible at or above the level of the heart to combat swelling. Regularly flexing and extending the fingers or wiggling the toes helps the blood to drain from the limb and also helps to prevent swelling. Pain, pressure, or numbness that remains constant or worsens over time should be reported to a doctor immediately. These conditions may be due to a developing pressure sore or compartment syndrome.

The combination of rest, ice, compression (for example, with a splint, cast, or sometimes an elastic bandage), and elevation is often called RICE therapy.

Surgical Treatment: Fractures sometimes require surgical treatment, as for the following:

Open fractures: A doctor must explore and carefully clean these fractures to remove all traces of foreign material that may have contaminated the bone ends.

Open fractures: A doctor must explore and carefully clean these fractures to remove all traces of foreign material that may have contaminated the bone ends.

Displaced fractures that cannot be aligned or kept aligned by closed reduction: When a bone fragment or a tendon is trapped in the bone ends, a doctor may not be able to reduce a displaced fracture. Sometimes the fracture can be reduced, but the natural pull of muscles on the fracture fragments keeps them from staying reduced.

Displaced fractures that cannot be aligned or kept aligned by closed reduction: When a bone fragment or a tendon is trapped in the bone ends, a doctor may not be able to reduce a displaced fracture. Sometimes the fracture can be reduced, but the natural pull of muscles on the fracture fragments keeps them from staying reduced.

Comminuted fractures: Multiple pieces are often too unstable for a cast to keep them aligned against the forces of muscle contraction.

Comminuted fractures: Multiple pieces are often too unstable for a cast to keep them aligned against the forces of muscle contraction.

Joint fractures: A near-perfect alignment of the joint surfaces is required to prevent people from developing arthritis later.

Joint fractures: A near-perfect alignment of the joint surfaces is required to prevent people from developing arthritis later.

Pathologic fractures: If possible, these fractures are stabilized surgically before they break further and become displaced. This approach avoids the pain, disability, and the more complex surgery involved with a displaced fracture.

Pathologic fractures: If possible, these fractures are stabilized surgically before they break further and become displaced. This approach avoids the pain, disability, and the more complex surgery involved with a displaced fracture.

Fractures of the thighbone (femur) and hip: If these fractures are not treated surgically, they require months of immobilization in bed before people are strong enough to bear weight. In contrast, surgical stabilization usually enables people to walk with crutches or a walker within days.

Fractures of the thighbone (femur) and hip: If these fractures are not treated surgically, they require months of immobilization in bed before people are strong enough to bear weight. In contrast, surgical stabilization usually enables people to walk with crutches or a walker within days.

Taking Care of a Cast

When bathing, enclose the cast in a plastic bag and carefully seal the top with rubber bands or tape. Commercially available waterproof covers are convenient to use and are more fail-safe. If a cast becomes wet, the underlying padding may retain moisture. A hair dryer can remove some dampness. Otherwise, the cast must be changed to prevent the breakdown of skin.

When bathing, enclose the cast in a plastic bag and carefully seal the top with rubber bands or tape. Commercially available waterproof covers are convenient to use and are more fail-safe. If a cast becomes wet, the underlying padding may retain moisture. A hair dryer can remove some dampness. Otherwise, the cast must be changed to prevent the breakdown of skin.

Never push a sharp or pointed object down inside the cast (for example, to scratch an itch).

Never push a sharp or pointed object down inside the cast (for example, to scratch an itch).

Check the skin around the cast every day, and apply lotion to any red or sore area.

Check the skin around the cast every day, and apply lotion to any red or sore area.

When resting, position the cast carefully, possibly using a small pillow or pad, to prevent the edge from pinching or digging into the skin. Chafing or pressure sores may develop where the skin is in contact with the edge of the cast. If the edge of the cast feels rough, it can be padded with soft adhesive tape, moleskin, tissues, or cloth.

When resting, position the cast carefully, possibly using a small pillow or pad, to prevent the edge from pinching or digging into the skin. Chafing or pressure sores may develop where the skin is in contact with the edge of the cast. If the edge of the cast feels rough, it can be padded with soft adhesive tape, moleskin, tissues, or cloth.

Elevate the cast regularly, as directed by the doctor, to control swelling.

Elevate the cast regularly, as directed by the doctor, to control swelling.

Contact a doctor immediately if the cast causes persistent pain or excessive tightness. Pressure sores or unexpected swelling may require immediate removal of the cast.

Contact a doctor immediately if the cast causes persistent pain or excessive tightness. Pressure sores or unexpected swelling may require immediate removal of the cast.

Contact a doctor if an odor emanates from the cast or if the person has a fever. These symptoms may indicate an infection.

Contact a doctor if an odor emanates from the cast or if the person has a fever. These symptoms may indicate an infection.

Surgery may also be needed to repair injury to ligaments, nerves, tendons, or major arteries.

Surgical stabilization involves first accurately reducing the fracture to restore the bone’s original shape and length. The surgeon uses anesthesia to relax the muscles and x-ray equipment to help align the bones. A surgeon exposes the fracture to see and manipulate the fragments with special instruments. Then, the bone fragments are securely fixed using some combination of metal wires, pins, screws, rods, and plates. This procedure is called open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). Metal plates are contoured and fixed to the outside of the bone with screws. Metal rods are inserted from one end of the bone into the marrow cavity. These implants are made of stainless steel, high-strength alloy metal, or titanium. All such implants made in the last 20 years are compatible with the strong magnets that are used for MRI. Most will not set off security devices at airports. Some of the hardware used to repair a fracture is permanently left in place, and some is removed after healing has taken place.

SPOTLIGHT ON AGING

Older people are more likely to have fractures because of the following:

Older people are more likely to have fractures because of the following:

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis

Frequent falls

Frequent falls

Impaired protective reflexes during falls

Impaired protective reflexes during falls

Age-related fractures often affect sections of the long bones. Fractures of the forearm, upper arm, leg, thigh, pelvis, and spine are common among older people.

Healing in older people is often slower than in younger adults. Also, because they typically have lower overall strength than younger people, it is harder for older people to compensate for the limitations caused by a fracture. Even minor fractures can significantly impair older people’s ability to do normal daily activities, such as eating, dressing, bathing, and even walking, especially if they use a walker. Their strength, flexibility, and balance may already be reduced, making the return to daily activities more difficult. If muscles are not used, they can become stiff and weak, further impairing them. Nurses and caregivers must help older people regain their ability to do normal daily activities.

Older people with poor circulation are at risk of pressure sores (see page 1299) when an injured limb rests on the cast. Nurses and caregivers should pad and diligently inspect the areas where the skin touches the cast (contact points)—especially the heels—for any sign of skin breakdown. Nurses and caregivers should make sure older people periodically change position to avoid stiffness. For example, sitting for a long time can lead to the hip and knee becoming fixed in a bent position. To help to prevent stiffness, people should periodically stand and walk or, if bedridden, alternate between lying down with the legs straight and sitting with the knees bent. For older people who are confined to bed, the risk of blood clots leading to pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, and urinary infections is high. Bed rest can also lead to pressure sores unrelated to a cast.

When treating fractures in older people, doctors try to avoid or minimize immobilization (joint immobilization or bed rest), which causes more problems in older people. Thus, the goal is to rapidly return older people to daily activities rather than perfectly restoring limb alignment and length.

A joint replacement procedure (arthroplasty) may need to be done when fractures severely damage the upper end of the femur, which is part of the hip joint, or humerus, which is part of the shoulder joint.

Bone grafting, using chips of bone harvested from another part of the body such as the pelvis, may be done initially, if the gap between fragments is too large, or later, if the healing process has slowed (delayed union) or stopped (nonunion).

Treatment of Compartment Syndrome: Anything confining the limb, such as a splint or a cast, is removed immediately. If this does not relieve pressure in the muscle compartment, an emergency surgical procedure called fasciotomy must be done. In fasciotomy, the doctor makes an incision along the entire length of the thick fibrous tissue (fascia) that makes up the compartment. This incision relieves pressure and allows blood flow to return to the muscles. Otherwise, the muscles and nerves could die because of a lack of oxygen, and then the limb may need to be amputated. If left untreated, complications of compartment syndrome can cause death.

Rehabilitation and Prognosis

Healing time varies from weeks to months. The outcome depends on the nature and location of the fracture. For many fractures, people eventually recover full function and have few or no symptoms. Some fractures, particularly those that involve a joint, can leave residual pain, stiffness, or both.

Stiffness and loss of strength are natural consequences of immobilization. A joint of a fractured limb immobilized in a cast becomes progressively stiffer each week, eventually losing its ability to fully extend and flex. Wasting away of muscle (atrophy) also can be severe. For instance, after wearing a long leg cast for a few weeks, most people can insert their hand into the formerly tight space between the cast and their thigh. When the cast is removed, the weakness resulting from muscle atrophy is very apparent.

Daily exercise using range-of-motion and muscle-strengthening exercises (see page 48) helps people combat stiffness and regain strength. While the fracture is healing, the joints outside the cast can be exercised. The joints within the cast cannot be exercised until the fracture has healed sufficiently and the cast can be removed. When exercising, the person should pay attention to how the injured limb feels and avoid exercising too forcefully. Passive exercises in which a therapist applies external force (see page 49) must be used when muscles are too weak for effective motion and when strong muscle contractions might displace a fracture. Ultimately, active exercise (in which the person uses his own muscle force) against gravity or weight resistance is necessary to regain full strength of an injured limb.

Foot and Ankle Fractures

Fractures of the foot bones are common and are caused by falls, twisting injuries, or direct impact of the foot against hard objects. Foot fractures cause considerable pain, which is almost always made worse by attempting to walk or put weight on the foot.

Diagnosis is usually made by x-ray. Rarely, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is required. Treatment varies with the bone involved and the type of fracture but usually involves placing the foot and ankle in a cast.

Toe Fractures: Toe (phalanges) fractures can occur when an unprotected foot collides with a hard object. If the big toe is abnormally bent, it may need to be realigned. Simple fractures of the four smaller toes heal without a cast. Certain measures, including splinting the toe with tape or nylon fastening (Velcro) to the adjacent toes (known as buddy taping) for several weeks and wearing loose footwear, can provide comfort and protect the toe. Stiff-soled shoes support the fracture, and wide, soft shoes place less pressure on the swollen toe. If walking in shoes is too painful, the doctor can prescribe specially fabricated boots.

A fracture of the big toe (hallux) tends to be more severe than that of the other toes, causing more intense pain, swelling, and bleeding under the skin. A big toe can break when a person drops a heavy object onto it or occasionally when a person stubs it. Fractures that affect the joint of the big toe may require surgery.

Sesamoid Fractures: The sesamoids are two small round bones located within the flexor tendon under the big toe. These bones may fracture from running, hiking, and sports involving coming down too hard on the ball of the foot (such as basketball and tennis). Using padding or specially constructed orthoses (insoles) for the shoe helps relieve the pain. If pain continues, a sesamoid bone may need to be removed surgically.

Metatarsal Fractures: A stress fracture of the metatarsals (the bones in the middle of the foot) can occur when a person walks or runs excessively (see page 1976). Putting full weight on the foot causes increased pain. The affected area on the metatarsal bone is tender to touch. Stress fractures may not be seen on x-rays if they are small or new (in an early stage). Sometimes CT, MRI, or bone scanning shows the fracture when x-rays do not. When a developing stress fracture is recognized early, stopping activities that aggravate the fracture may be all that is necessary. In more advanced and severe cases, crutches and a cast are necessary.

A fracture and dislocation of the base of the 2nd metatarsal bone usually occurs when people fall in a way that causes the toes to bend or twist toward the sole of the foot. This injury, called Lisfranc’s fracture-dislocation, is common among football players. The middle of the foot becomes painful, swollen, and tender. Lisfranc’s fracture-dislocation is serious and can lead to chronic problems with strenuous activities, permanent pain, and arthritis. Surgery may be required but does not always restore the foot to its previous condition.

A fracture of the 5th metatarsal base (located at the outside edge of the middle of the foot) occurs commonly after the foot is injured by turning inward or is crushed. This fracture is sometimes called a dancer’s fracture. The outside edge of the foot becomes tender, and a swollen bruise develops. The cause and symptoms may be similar to those of a sprained ankle. A cast is not usually necessary but can make walking easier. Crutches and a protective walking shoe may be needed for a few days. These fractures heal relatively quickly. Fractures of the shaft of the 5th metatarsal bone (Jones fractures) are less common than dancer’s fractures and do not heal as easily.

Heel Fractures: A heel fracture can occur if people land on their feet after falling from a height. Sometimes the knees, spine, or both also are injured in such a fall. Heel fractures are very painful, and people are unable to bear weight on the foot. Surgery is sometimes needed.

Foot Fractures

Foot fractures are common. They may occur in the toes, the middle bones of the foot (metatarsals), the two small round bones just below the big toe (sesamoids), or the ankle bones. The big toe (hallux) is the toe most often fractured.

Ankle Fractures: The ankle may fracture when the foot rolls inward or outward during a fall or while running or jumping. Fractures usually involve the bony bump on the outside of the ankle (lateral malleolus), which is the end of the small bone of the lower leg (fibula). Less often, the bump on the inside of the ankle is involved. This bump is the end of the large bone of the lower leg (tibia). Sometimes both are affected, in which case there is usually significant ligament damage as well. Nondisplaced fractures of the ankle can be treated with a cast. Displaced fractures that cannot be realigned by the doctor or held in place with a cast require surgery.

Small chip (avulsion) fractures of the ligament attachments are similar to a severe sprain. This type of fracture is treated with a brace or cast for 6 weeks and usually heals well.

Leg Fractures

Tibia Fractures: Fractures of the shaft of the tibia (situated between the knee and the ankle) usually result from high-energy injuries, such as motor vehicle accidents, collisions, falls during skiing, and when pedestrians are struck by a car. This type of fracture can be very serious, particularly if the skin, muscle, nerves, or blood vessels are damaged. Such damage can lead to compartment syndrome (see page 1953).

For closed fractures of the tibia, an above-the-knee cast is needed until healing is under way and is then changed to a below-the-knee cast. The total time the person needs to wear these casts is usually about 3 months, but healing can take much longer. Many of these closed fractures are treated surgically with metal rods or plates. After surgery, usually no cast is required, and rehabilitation can begin sooner. If the skin is severely damaged and bare bone is exposed, an external fixator (a frame of rods clamped to stainless steel pins that pass through the skin into the bone) is used.

Femur Fractures: Fractures of the shaft of the femur (the large bone above the knee) are serious injuries usually caused by falls from a height or high-speed motor vehicle accidents. Special traction equipment is needed for transport to the hospital. In adults, these fractures are treated with urgent surgery to align and fixate the fracture with metal rods or plates (a procedure known as open reduction and internal fixation, or ORIF). After surgery, most people begin to walk with crutches immediately.

Hip Fractures

Hip fractures, which occur most frequently among older people, can be caused by minor falls, particularly among people with osteoporosis.

Hip fractures, which occur most frequently among older people, can be caused by minor falls, particularly among people with osteoporosis.

Most people with a hip fracture cannot move the leg, stand, or walk.

Most people with a hip fracture cannot move the leg, stand, or walk.

Hip fractures are diagnosed with x-rays or sometimes other imaging tests.

Hip fractures are diagnosed with x-rays or sometimes other imaging tests.

Surgery is usually done, and sometimes the joint is replaced.

Surgery is usually done, and sometimes the joint is replaced.

More than 270,000 hip fractures occur in the United States each year, with about 90% of them occurring in people older than 60. Hip fractures are more common in older people because of osteoporosis and because older people are more likely to fall. Use of some drugs increases the risk of hip fractures in older people (see page 1896). One in 3 women and 1 in 6 men who reach age 90 will fracture a hip. Hip fractures in older people can lead to life-threatening complications, such as blood clots and pneumonia. Hip fractures sometimes change how people live. For example, people who have a hip fracture may need supervised care or have to move to a nursing home.

The upper end of the thighbone (femur) has large bony bumps (trochanters) where powerful muscles attach, then a short neck, and finally a spherical head that forms the outer half of the hip joint. Most hip fractures occur just below the spherical head (femoral neck or subcapital hip fractures) or through the trochanters (intertrochanteric hip fractures).

Femoral neck hip fractures are particularly problematic because the fracture often disrupts the blood supply to the femoral head, which forms the hip joint. Without a good blood supply, the bone cannot heal and eventually collapses and dies. These fractures can be caused by minimal force, such as walking, in people with osteoporosis and may be stress fractures.

Intertrochanteric hip fractures tend to create large broken bone surfaces that cause internal bleeding. These fractures usually result from a fall or direct blow.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Most older people with fractured hips cannot move their leg, much less stand or walk. When a doctor examines the person, the leg may appear shortened and turned outward because of the unbalanced pull of muscles. Swelling and a purplish bruise may develop because of blood leaking from the fracture. Hip fractures can cause pain in the knee, called referred pain.

An x-ray usually shows an obvious fracture and can help a doctor confirm the diagnosis. However, faint fracture lines may not be seen initially on an x-ray. Thus, when a doctor still suspects a hip fracture or the person continues to have pain and is unable to stand a day or more after a fall, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) may be done.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Surgery is the preferred treatment for hip fractures in older people because it allows people to walk sooner and avoid serious problems that can result from staying in bed too long.

Treatment

Most people with a hip fracture are treated with surgery. If people with hip fractures are forced by their injury to stay in bed, they are at increased risk of developing serious complications, such as pressure sores, blood clots leading to pulmonary embolism, mental confusion, and pneumonia. A great benefit of surgery is that it allows the person to get out of bed and begin walking as soon as possible. Usually, the person can take a few steps with a walker 1 to 2 days after the operation. Physical rehabilitation is started as soon as possible (see page 54).

The type of surgery depends on the type of fracture.

Femoral neck hip fractures may be repaired with metal pins or by removing the broken pieces and replacing the head of the femur with a metal implant (partial hip replacement). An implant may be needed when the blood supply to the femoral head has been damaged.

Intertrochanteric hip fractures are treated with a sliding compression screw and side plate, which holds the bone fragments in their proper position while the fracture heals. The fixation is usually strong enough to permit people to bear weight shortly after surgery. Although the bone fragments usually heal in a couple of months, most people need at least 6 months to fully regain their original level of comfort, strength, and walking ability.

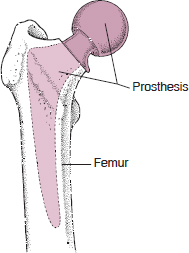

Partial Hip Replacement: If partial hip replacement is needed, doctors use special metallic implants. These implants have a polished spherical surface to match the joint socket and a strong stem to fit within the central marrow canal of the thighbone. Some prosthetic implants are secured to the bone with a rapid-setting plastic cement. Others have special porous or ceramic coatings into which the surrounding living bone can grow and bond directly.

After joint replacement surgery, the person usually begins walking with crutches or a walker immediately and switches to a cane in 6 weeks. However, artificial joints do not last forever. The person, especially someone who is active or heavy, may need to undergo another operation 10 to 20 years later. Joint replacement is often advantageous for older people, because the likelihood that additional surgery will be needed is very low. In addition, older people benefit greatly from being able to walk almost immediately after surgery.

Sometimes the whole joint needs to be replaced. This procedure is commonly done to treat osteoarthritis. Whole-joint replacement is rarely used to treat fractures.

Repairing a Fractured Hip

There are two common types of hip fractures. Femoral neck or subcapital hip fractures occur in the neck of the thighbone (femur). Intertrochanteric fractures occur in the large bony bumps (trochanters) where the powerful muscles of the buttocks and legs attach. When the fracture is not too severe, metal pins can be inserted surgically to support the femoral head. This surgical procedure preserves the person’s own hip joint.

Replacing a Hip

When the topmost part (head) of the thighbone (femur) is badly damaged, it may be replaced with an artificial part (prosthesis), made of metal (usually a Moore prosthesis). This procedure is called partial hip replacement. Very rarely, the socket into which the femoral head fits (forming the hip joint) must also be replaced. The part used is a metal shell lined with durable plastic. This procedure is called total hip replacement.

Pelvis Fractures

The pelvis is made up of pairs of large broad (iliac) bones in the back joined by two smaller connecting bone struts (the pubic and ischial rami) in the front. In young adults, major fractures of the entire pelvis can occur as a result of high-speed motor vehicle accidents or falls from a height. These fractures can cause life-threatening bleeding and injury to internal organs. In older people, the rami, often weakened by osteoporosis, can fracture from even a minor fall on level ground.

Symptoms

With fractures of the pelvic rami, most people feel considerable pain in the groin, even when lying down or sitting. The pain becomes much worse when people try to walk, although some are able.

People with major pelvic fractures have severe pain and are unable to walk.

Diagnosis

Doctors suspect a pelvic fracture based on the symptoms and confirm the diagnosis using x-rays. Sometimes, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is required.

Prognosis and Treatment

People usually need to be admitted to a hospital or rehabilitation center.

Stable fractures of the pelvic rami typically heal without causing permanent disabilities and rarely require surgical treatment. Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs—see page 644) help relieve pain and inflammation. To avoid the weakness, stiffness, and other complications that occur with bed rest, walking and bearing weight fully should begin as soon as possible. People with fractures of the rami can try to walk without causing further injury to the area. Most people can walk short distances with a walker by 1 week and are moderately comfortable in 1 to 2 months.

Major pelvic fractures are often unstable and require immobilization. Doctors sometimes attach a rigid metal frame to the pelvis using screws driven into the bone. Permanent disability often results if the socket of the hip joint has been damaged. Because of the large amount of force required to cause a major pelvic fracture, internal organs are also often damaged. The mortality rate for this type of injury is high.

Compression Fractures of the Spine

Compression fractures may occur with only slight trauma in older people with osteoporosis.

Compression fractures may occur with only slight trauma in older people with osteoporosis.

The area around the fracture is painful, and the pain worsens with walking, standing, and prolonged sitting.

The area around the fracture is painful, and the pain worsens with walking, standing, and prolonged sitting.

Doctors diagnose spinal compression fractures with x-rays.

Doctors diagnose spinal compression fractures with x-rays.

Treatment can include braces, comfort measures, and sometimes injection of bone cement into the fractured bone.

Treatment can include braces, comfort measures, and sometimes injection of bone cement into the fractured bone.

In a compression fracture of the spine, the cylindrical-shaped part of the back bone (vertebra) that makes up the column of the spine and bears most of the weight, becomes compressed into a wedge shape. These fractures usually occur in older people, typically those with osteoporosis. Sometimes, cancer that has spread to the spine weakens it and causes compression fractures. Compression fractures of the spine can occur with slight trauma or even with lifting, bending forward, or taking a misstep. Sometimes people do not remember any event that might have caused the fracture.

Other fractures of the spine are discussed elsewhere (see page 798).

Symptoms

Compression fractures cause constant, dull back pain that may worsen with standing, walking, or prolonged sitting. When the doctor gently taps over the spine, the person feels discomfort. Because the spinal cord and nerve roots are contained within the spine, the cord or nerve roots very rarely may be injured, which may result in paralysis and a loss of sensation. Other symptoms of nerve injury include pain radiating into the leg, weakness of the leg muscles, and involuntary wetting or soiling of clothing with urine or stool (incontinence).

If compression fractures occur over time at several levels of the spine, a person can lose several inches of height, develop a humpback deformity, and be unable to stand up straight.

Diagnosis

Doctors use x-rays to confirm the diagnosis, check the spine for stability, and exclude the possibility of cancer.

Treatment

Braces are most effective for fractures located in the lower part of the spine. They can relieve pain and enable the person to more rapidly return to daily activities. Initially, bed rest may be required for a few days, but sitting up and walking for short periods as soon as possible can help prevent loss of function and further loss of bone density.

In older people, compression fractures of the spine that are not complicated by instability, nerve injury, or cancer heal on their own but slowly. Treatment often is limited to comfort measures.

Two minimally invasive procedures can sometimes be done to help relieve pain and possibly restore height and improve appearance:

Vertebroplasty: A material called polymethyl-methacrylate—an acrylic bone cement—is injected into the collapsed vertebra. This procedure takes about an hour for each vertebra.

Vertebroplasty: A material called polymethyl-methacrylate—an acrylic bone cement—is injected into the collapsed vertebra. This procedure takes about an hour for each vertebra.

Kyphoplasty: In this similar procedure, a balloon is inserted into the vertebra and is expanded to restore the vertebra to its normal shape. Then bone cement is injected.

Kyphoplasty: In this similar procedure, a balloon is inserted into the vertebra and is expanded to restore the vertebra to its normal shape. Then bone cement is injected.

Neither of these procedures reduces the risk of fractures in adjacent bones in the spine or ribs. This risk may even increase. Other risks may include leakage of the cement and possibly heart or lung problems.

Rib Fractures

Rib fractures usually result from a strong force, such as falls, motor vehicle accidents, or a hit with a baseball bat. However, sometimes in older people, only a slight force (such as a minor fall) is required. The fracture itself is rarely serious, although internal organs (such as the lung, liver, or spleen) are occasionally damaged by the force that causes the fracture. The more ribs that are injured, the more likely people are to have damage to the lung or other organs.

Rib fractures cause severe pain, particularly with deep breathing, and the pain lasts for weeks.

Some rib fractures are not visible on initial x-rays, especially if the bone is not displaced or if the person has osteoporosis.

Regardless of whether rib fractures are seen on imaging tests, treatment can be started. Opioid analgesics are usually used. Also, while awake, people with a rib fracture must cough or breathe deeply about once an hour. If they do not, small areas of the lung may collapse, possibly leading to pneumonia.

Clavicle Fractures

Clavicle fractures occur commonly after a fall on an outstretched arm or after a direct blow. Because the clavicle lies just under the skin and has little muscle covering, swelling and deformity are easily seen after a fracture. Most of these injuries involve the middle third of the bone and are immobilized with a sling. Surgery is occasionally needed.

Another clavicle injury involves partial or complete separation of the outer part of the clavicle from its attachment to the rest of the shoulder. This attachment is the acromioclavicular joint, so the injury is called an acromioclavicular separation or sprain or injury. It is sometimes called a shoulder separation. It usually results from a fall onto the outside of the shoulder. The injury is usually painful but not serious. No surgery is required unless it is severe. Sometimes the end of the clavicle sticks up from its attachment, resulting in a permanent bump that may be seen or felt.

Humerus Fractures

Fractures of the upper arm bone (humerus) usually occur near the shoulder. These fractures are common after a fall on an outstretched arm or after a direct blow. Symptoms include pain and an inability to raise the arm. Fractures of the middle of the humerus sometimes damage the radial nerve. Radial nerve damage leads to an inability to lift up the wrist. Most of these fractures can be treated with a sling and swathe. Surgery is needed if the fracture pieces are widely separated. If the fracture affects the shoulder joint, a prosthetic implant (partial shoulder replacement) may be needed.

Elbow Fractures

Elbow fractures can involve any of the three bones that make up the joint (radius, ulna, and humerus). Fractures of the radial head or neck (the upper end of the radius) occur commonly in active adults after a fall on an outstretched arm. The outer side of the elbow is painful, and people cannot fully straighten the arm. Fractures of the upper arm bone (humerus) are more serious, often affecting the nerves.

X-rays usually show a fracture, but sometimes the only sign is fluid around the elbow joint.

Most radial head fractures are mild and can be treated with a splint or a sling and early (within a few days) gentle range-of-motion exercises. Early motion helps prevent permanent stiffness. More severe radial head fractures may require surgical treatment.

Wrist Fractures

Wrist fractures involve the radius, and sometimes also the ulna. Certain types of wrist fractures are called Colles’ fractures. These occur commonly after a fall on an outstretched arm, particularly in older people. People have pain, swelling, and tenderness, and often the wrist appears in an unnatural position.

For many fractures, closed reduction followed by casting is adequate. The cast may be worn for 3 to 6 weeks. Other wrist fractures require surgery, particularly if the joint surface is out of place, especially in active adults who need to be able to fully use their wrist. During surgery, an internal plate may be applied, or an external fixator (a frame of rods clamped to stainless steel pins that pass through the skin into the bone) is used.

Daily motion of the fingers, elbow (if free), and shoulder helps to avoid stiffness. Elevation of the hand is important to control swelling. Comfort, flexibility, and strength of the wrist continue to improve for 6 to 12 months after the fracture.

Hand Fractures

Hand fractures involve the bones that form part of the wrist (carpals), bones of the palm (metacarpals), or bones of the fingers and thumb (phalanges). Normal hand function results from a complex interaction of an intricate arrangement of muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joints, as well as bones. Thus, seemingly minor fractures can cause serious soft tissue injuries that, if not treated appropriately, can lead to disabling stiffness, weakness, or deformity.

Carpal Fractures: A carpal bone that is commonly fractured is the scaphoid bone (see box on page 604). A fracture of the scaphoid bone usually occurs with a fall on an outstretched hand. Symptoms include pain while rotating the palm and, particularly, tenderness at the hollow at the base of the thumb or pain when the thumb is pushed into the wrist. Because the initial x-ray is often normal, people who have a suspected fracture require splinting and re-examination in 7 to 10 days, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is more sensitive than an x-ray. The fracture may be treated with a thumb spica splint. Scaphoid bone fractures are prone to poor healing because the blood supply is often damaged when the bone is fractured. About 5% of the time, regardless of treatment, the bone eventually dies (called necrosis). If so, bone grafting may be necessary.

Metacarpal Fractures: Fractures of the ends of the 4th and 5th metacarpal bones (that attach to the ring finger and little finger) commonly occur from punching a hard object. This type of fracture, called a boxer’s fracture, causes swelling and tenderness of the knuckle. These fractures are treated with a splint. Reduction is necessary only if the fracture is badly angled or rotated. Typically, good function of the finger returns.

Finger Fractures: Avulsion fractures occur commonly in the fingers at the site of tendon and joint capsule attachments. A mallet finger injury refers to the drooping of the fingertip that occurs when the tendon that extends the farthest part of the finger becomes detached (see page 598). A common cause is a baseball that strikes the fingertip (baseball finger). For simple mallet finger injuries, immobilization with a splint for 6 to 10 weeks is effective, but if avulsion fractures greatly disrupt the joint surface, surgery may be needed.

Fingertip fractures are usually the result of a crush injury, such as from a hammer blow. Blood may accumulate beneath the nail (subungual hematoma) from a tear in the nail bed and produce a very painful, blue-black discoloration. Most fingertip fractures are treated with a protective covering (such as commercially available aluminum and foam splint material) wrapped around the fingertip. Doctors can easily drain a subungual hematoma by making a small hole in the fingernail with a needle or a hot wire (electrocautery device).

Large, displaced finger fractures are repaired with surgery. An abnormal increase in sensitivity (hyperesthesia) frequently lasts long after a large fracture has healed. The person may require treatment to decrease hyperesthesia (desensitization therapy).