CHAPTER 311

Bites and Stings

Many creatures, including humans, bite when frightened or provoked. Bites may cause injuries ranging from superficial scratches to extensive wounds and often become infected with bacteria from the mouth of the biting creature.

Certain animals can inject venom (poison) through mouthparts or a stinger. These venoms range in toxicity from mild to life threatening. Even mildly toxic venoms may cause serious allergic reactions.

Doctors diagnose most bites and stings by talking with and examining the person. If a wound is deep, x-rays or other imaging studies are sometimes done to look for teeth or other hidden foreign material. The most effective way to prevent infection and scarring is usually thorough cleaning and proper wound care, done as soon as possible.

Animal Bites

Most animal bites in the United States are from dogs and cats.

Most animal bites in the United States are from dogs and cats.

Wounds should be cleaned and cared for as soon as possible.

Wounds should be cleaned and cared for as soon as possible.

Although any animal may bite, dogs and, to a lesser extent, cats account for most bites in the United States. Owing to their popularity as household pets, dogs account for the majority of bites as a result of protecting their owners and territory. About 10 to 20 people, mostly children, die from dog bites each year. Cats do not defend territory and bite mainly when humans restrain them or attempt to intervene in a cat fight. Domestic animals, such as horses, cows, and pigs, bite infrequently, but their size and strength are such that serious wounds may result. Wild animal bites are rare.

Dog bites typically have a ragged, torn appearance. Cat bites involve deep puncture wounds that frequently become infected. Infected bites are painful, swollen, and red. Rabies (see page 757) may be transmitted from animals (most commonly bats, raccoons, foxes, and skunks) infected with that organism. Rabies is rare among pets in the United States because of vaccination. Squirrel, hamster, and rodent bites rarely transmit rabies.

Treatment

After receiving routine first-aid treatment (see page 1946), people who have been bitten by an animal should see a doctor immediately. If possible, the offending animal should be penned up by its owner. If the animal is loose, the person who has been bitten should not try to capture it. The police should be notified so that the proper authorities can observe the animal for signs of rabies.

Doctors clean an animal bite by flooding the wound with sterile salt water (saline) and cleansing it with soap and water. Sometimes tissue is trimmed from the edge of the bite wound, particularly if the tissue is crushed or ragged. Facial bite wounds are closed surgically (sutured). However, minor wounds, puncture wounds, and bite wounds to the hands are not closed. Antibiotics are sometimes given by mouth to prevent infection. Infected bites sometimes require surgical drainage, antibiotics given intravenously, or both.

Human Bites

A human bite wound to the hand sustained by punching someone in the mouth often becomes infected.

A human bite wound to the hand sustained by punching someone in the mouth often becomes infected.

Wounds should be cleaned, and antibiotics should be given.

Wounds should be cleaned, and antibiotics should be given.

Because human teeth are not particularly sharp, most human bites cause a bruise and only a shallow tear (laceration), if any. Exceptions are on fleshy appendages, such as the ears, nose, and penis, which may be severed. The clenched-fist injury, or fight bite, which occurs on the knuckles of a person who punches another person in the mouth, is likely to become infected (see page 603). Hospitalization may be needed for administration of intravenous antibiotics. A clenched-fist cut frequently involves the finger tendon that passes over the knuckle. Sometimes the biting person transmits diseases, such as hepatitis. Transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is extremely unlikely because the concentration of the virus in saliva is lower than that in blood and because substances in saliva inhibit the virus’s activity.

Symptoms

Bites are painful and usually produce a mark on the skin with the pattern of the teeth. Fight bites leave only a small, straight cut over a knuckle. A lacerated finger tendon often results in difficulty moving the finger in one direction. Infected bites become very painful, red, and swollen.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Transmission of HIV infection with a human bite wound is highly unlikely.

Treatment

Human bites are cleaned by flooding the wound with sterile salt water (saline) and cleansing it with soap and water. Severed parts can sometimes be reattached. Tears, except those involving the hand and those that have occurred many hours ago, are surgically closed. All people with human bites that have broken the skin are given antibiotics by mouth to prevent infection. Infected bites are treated with antibiotics and often must be opened surgically to examine and clean the wound. If the biting person is known or suspected to have a disease that may be spread by biting, preventive treatment may be necessary.

Snake Bites

Venomous snakes in the United States include pit vipers (rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths) and coral snakes.

Venomous snakes in the United States include pit vipers (rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths) and coral snakes.

Severe envenomation can cause damage to the bitten extremity, bleeding, and vital organ damage.

Severe envenomation can cause damage to the bitten extremity, bleeding, and vital organ damage.

Venom antidote is given for serious bites.

Venom antidote is given for serious bites.

Bites from nonpoisonous snakes rarely produce any serious problems. About 25 species of venomous (poisonous) snakes are native to the United States. The venomous snakes include pit vipers (rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths) and coral snakes. Of the roughly 45,000 snakebites that occur in the United States each year, fewer than 8,000 are from venomous snakes, and about six people die. Fatal snakebites are much more common outside the United States.

In about 25% of all pit viper bites, venom is not injected. Most deaths occur in children, older people, and people who are untreated or treated too late or inappropriately. Rattlesnakes account for about 70% of poisonous snakebites in the United States and for almost all of the deaths. Copperheads and, to a lesser extent, cottonmouths account for most other poisonous snakebites. Coral snake bites and bites from imported snakes are much less common.

The venom of rattlesnakes and other pit vipers damages tissue around the bite. Venom may produce changes in blood cells, prevent blood from clotting, and damage blood vessels, causing them to leak. These changes can lead to internal bleeding and to heart, respiratory, and kidney failure. The venom of coral snakes affects nervous system activity but causes little damage to tissue around the bite. Most bites occur on the hand or foot.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Snake bites can be terrifying but rarely cause deaths in the United States.

Symptoms

The symptoms of snake venom poisoning vary widely, depending on the following:

The size and species of snake

The size and species of snake

The amount and toxicity of the venom injected (related to the size and species of snake)

The amount and toxicity of the venom injected (related to the size and species of snake)

The bite’s location (the farther away from the head and trunk, the less dangerous)

The bite’s location (the farther away from the head and trunk, the less dangerous)

The person’s age (very old and very young people are at higher risk)

The person’s age (very old and very young people are at higher risk)

The person’s underlying medical problems

The person’s underlying medical problems

Pit Vipers: Bites by most pit vipers rapidly cause pain. Redness and swelling usually follow within 20 to 30 minutes and can affect the entire leg or arm within several hours. People bitten by a rattlesnake may experience tingling and numbness in the fingers or toes or around the mouth and a metallic or rubbery taste in the mouth. Other symptoms include fever, chills, general weakness, faintness, sweating, anxiety, confusion, and nausea and vomiting. Some of these symptoms may be caused by terror rather than venom. Breathing difficulties can develop, particularly after Mojave rattlesnake bites. People may have a headache, blurred vision, drooping eyelids, and a dry mouth.

Moderate or severe pit viper poisoning commonly causes bruising of the skin 3 to 6 hours after the bite. The skin around the bite appears tight and discolored. Blisters, often filled with blood, may form in the bite area. Without treatment, tissue around the bite may be destroyed. The gums may bleed, and blood may appear in the person’s vomit, stools, and urine.

Coral Snakes: Coral snake bites usually cause little or no immediate pain and swelling. More severe symptoms may take several hours to develop. The area around the bite may tingle, and nearby muscles may become weak. Muscle incoordination and severe general weakness may follow. Other symptoms may include double vision, blurred vision, confusion, drowsiness, increased saliva production, and speech and swallowing difficulties. Breathing problems, which may be extreme, may develop.

Diagnosis

Emergency medical personnel must try to determine whether the snake was poisonous, what species it was, and whether venom was injected. The bite marks sometimes suggest whether the snake was poisonous. The fangs of a poisonous snake usually produce one or two large punctures, whereas the teeth of nonpoisonous snakes usually leave multiple small rows of scratches. Without a detailed description of the snake, doctors may have difficulty determining the particular species that caused the bite. Envenomation is recognized by the development of characteristic symptoms. People who are bitten by a poisonous snake are generally kept in the hospital for observation for 6 to 8 hours to see if any symptoms develop. Doctors do various tests to assess the effects of the venom.

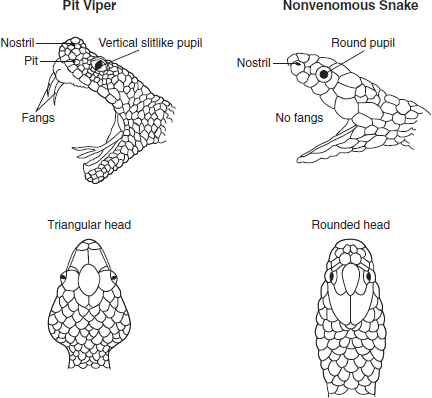

Is That a Pit Viper?

Pit vipers have certain features that can help distinguish them from nonvenomous snakes:

Triangular heads (like an arrowhead)

Triangular heads (like an arrowhead)

Vertical slitlike pupils

Vertical slitlike pupils

Pits between the eyes and nose

Pits between the eyes and nose

Retractable fangs

Retractable fangs

Rows of single scales across the underside of the tail

Rows of single scales across the underside of the tail

Nonvenomous snakes tend to have the following:

Rounded heads

Rounded heads

Round pupils

Round pupils

No pits

No pits

No fangs

No fangs

Rows of double scales across the underside of the tail

Rows of double scales across the underside of the tail

If people see a snake with no fangs, they should not assume it is nonvenomous because the fangs may be retracted.

Treatment

First aid can be helpful before medical help arrives. People bitten by a poisonous snake should be moved beyond the snake’s striking distance, kept as calm and still as possible, and taken to the nearest medical facility immediately. The bitten limb should be loosely immobilized and kept positioned just below heart level. Rings, watches, and tight clothing should be removed from the area of the bite. Alcohol and caffeine should be avoided. Tourniquets, ice packs, and cutting the bite open are not recommended because they are potentially harmful.

What Is Serum Sickness?

Serum sickness is a reaction by the immune system against large amounts of foreign protein that have entered the bloodstream. A common source of such foreign protein is horse serum, an ingredient present in many venom antidotes (antivenoms) that are used to treat poisonous snake and spider bites and scorpion stings. Symptoms of serum sickness include fever, rash, and joint pains. Rarely, kidney damage and death can occur. Doctors treat serum sickness with antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine, and corticosteroids. Antivenoms that do not contain horse serum are unlikely to result in serum sickness.

If no venom was injected, treatment is the same as for any puncture wound (see page 1946).

Venom antidote (antivenom) is the most important part of treatment if venom was injected and symptoms indicate a serious bite. Antivenom is more effective the sooner it is given. Antivenom neutralizes venom’s toxic effects. It is given intravenously and is available for all native poisonous snakes. Pit viper antivenom made from horse serum frequently causes serum sickness (an immune system reaction against foreign protein). Newer antivenom made of purified antibody fragments from sheep is less likely to cause serum sickness.

Intensive care unit treatment is required for people with severe envenomation. People are monitored closely, and the complications of envenomation are treated. People with low blood pressure are given fluids intravenously. If problems with blood clotting develop, fresh frozen plasma, concentrated clotting factors (cryoprecipitate), or platelet transfusions are given.

Prognosis depends on the person’s age and overall health and on the location and venom content of the bite. Almost everyone bitten by a poisonous snake survives if treated early with appropriate amounts of antivenom.

Lizard Bites

The only two lizards known to be poisonous are the beaded lizard of Mexico and the Gila monster, present in Arizona; Sonora, Mexico; and adjacent areas. The venom of these lizards is somewhat similar in content and effect to that of some pit vipers, although symptoms tend to be much less severe, and bites are almost never fatal. Unlike most snakes, the Gila monster and beaded lizard clamp on firmly when they bite and chew the venom into the person rather than injecting it through fangs. The lizard may be difficult to dislodge.

Common symptoms include pain, swelling, and discoloration in the area around the bite as well as swollen lymph nodes. Weakness, sweating, thirst, headache, and ringing in the ears (tinnitus) may develop. In severe cases, blood pressure may fall.

Various suggestions for removing Gila monsters include the following:

Forcing the jaws open with pliers

Forcing the jaws open with pliers

Applying a flame under the lizard’s chin

Applying a flame under the lizard’s chin

Immersing the lizard and body extremity under water

Immersing the lizard and body extremity under water

Once the lizard has been detached, tooth fragments often remain in the skin and must be removed. Treatment of low blood pressure or blood clotting problems is similar to that of pit viper bites. A specific antivenom is not available.

Spider Bites

Serious injuries from spider bites can include severe wounds caused by brown spiders and bodywide poisoning caused by widow spiders.

Serious injuries from spider bites can include severe wounds caused by brown spiders and bodywide poisoning caused by widow spiders.

Wounds suspected of being caused by the brown spider are often caused by other problems, some potentially more serious.

Wounds suspected of being caused by the brown spider are often caused by other problems, some potentially more serious.

Widow spider bites are treated by relieving symptoms and sometimes giving antivenom.

Widow spider bites are treated by relieving symptoms and sometimes giving antivenom.

Brown spider bites are treated by caring for the wound.

Brown spider bites are treated by caring for the wound.

Almost all spiders are poisonous. However, the fangs of most species are too short or too fragile to penetrate human skin. Although at least 60 species in the United States have been implicated in biting people, serious injury occurs mainly from only two types of spiders:

The widow (black widow) spider

The widow (black widow) spider

The brown (brown recluse, fiddleback, or violin) spider

The brown (brown recluse, fiddleback, or violin) spider

Brown spiders are present in the Midwest and South Central United States, not in the coastal and Canadian border states, except when imported on clothing or luggage. Widow spiders are present throughout the United States. Although some people consider tarantulas dangerous, their bites do not seriously harm people. Spider bites cause fewer than three deaths a year in the United States, usually in children.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Although tarantulas are large and may appear frightening, their bites do not seriously harm people.

Symptoms

The bite of a widow spider usually causes a sharp pain, somewhat like a pinprick, followed by a dull, sometimes numbing, pain in the area around the bite. Cramping pain and muscle stiffness, which may be severe, develop in the abdomen or the shoulders, back, and chest. Other symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, sweating, restlessness, anxiety, headache, drooping and swelling of the eyelids, rash and itching, severe breathing problems, increased saliva production, and weakness.

The bite of a brown spider may cause little or no immediate pain, but some pain develops in the area around the bite within about an hour. Pain may be severe and may affect the entire injured area, which may become red and bruised and may itch. The rest of the body may itch as well. A blister forms, surrounded by a bruised area or by a more distinct red area that resembles a bull’s-eye. Then the blister enlarges, fills with blood, and ruptures, forming an open sore (ulcer) that may leave a large crater-like scar. Uncommonly, nausea and vomiting, aches, fatigue, chills, sweats, blood disorders, and kidney failure develop.

Diagnosis

There is no way to identify a particular spider on the basis of its bite mark. Therefore, a specific diagnosis can be made only if the spider can be identified. Widow spiders are recognized by a red or orange hourglass-shaped marking on the abdomen. Brown spiders have a violin-shaped marking on their back. However, these identifying marks can be difficult to discern, and the spider is rarely retrieved intact, so the diagnosis is usually uncertain and based on symptoms. Many people mistake skin infections, some potentially serious (such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] infections), or other disorders for spider bites.

Treatment

First-aid measures for a spider bite include cleaning the wound, placing an ice cube on the bite to reduce pain, and, if the bite is on an extremity, elevating the wound site.

For a widow spider bite, muscle pain and spasms can be relieved with muscle relaxants and analgesics. If the pain and spasms are severe, calcium given by vein (intravenously) may be required. Hot baths may relieve mild pain. Antivenom is given for severe poisoning. Hospitalization is usually required for people younger than 16 or older than 60 and for people with high blood pressure, heart disease, or severe symptoms.

Did You Know…

Did You Know…

Many people falsely assume that they were bitten by a spider when they really have another disorder, such as a skin infection.

Most brown spider bites heal without complications. Sores should be cleaned daily with a povidone-iodine solution and soaked 3 times a day in sterile salt water (saline). Moderately to severely damaged wounds may require surgical procedures.

Bee, Wasp, Hornet, and Ant Stings

Stings by bees, wasps, hornets, and ants usually cause pain, redness, swelling, and itching.

Stings by bees, wasps, hornets, and ants usually cause pain, redness, swelling, and itching.

Allergic reactions are uncommon but may be serious.

Allergic reactions are uncommon but may be serious.

Stingers should be removed, and a cream or ointment can help relieve symptoms.

Stingers should be removed, and a cream or ointment can help relieve symptoms.

Stings by bees, wasps, and hornets are common throughout the United States. Some ants also sting. The average person can safely tolerate 10 stings for each pound of body weight. This means that the average adult could withstand more than 1,000 stings, whereas 500 stings could kill a child. However, one sting can cause death from an anaphylactic reaction (a life-threatening allergic reaction in which blood pressure falls and the airway closes—see page 1123) in a person who is allergic to such stings. In the United States, 3 or 4 times more people die from bee stings than from snakebites. A more aggressive type of honeybee, called the Africanized killer bee, has reached the southern and some southwestern states from South America. By attacking their victim in swarms, these bees cause a more severe reaction than do other bees.

In the South, particularly in the Gulf region, fire ants sting up to 40% of the people who live in infested areas each year, causing at least 30 deaths.

Symptoms

Bee, wasp, and hornet stings produce immediate pain and a red, swollen, sometimes itchy area about 1/2 inch (about 1 centimeter) across. In some people, the area swells to a diameter of 2 inches (5 centimeters) or more over the next 2 or 3 days. This swelling is sometimes mistaken for infection, which is unusual after bee stings. Allergic reactions may cause rash, itching all over, wheezing, trouble breathing, and shock.

The fire ant sting usually produces immediate pain and a red, swollen area, which disappears within 45 minutes. A blister then forms, rupturing in 2 to 3 days, and the area often becomes infected. In some cases, a red, swollen, itchy patch develops instead of a blister. Isolated nerves may become inflamed, and seizures may occur.

Treatment

A bee may leave its stinger in the skin. The stinger should be removed as quickly as possible by scraping with a thin dull edge (for example, the edge of a credit card or a thin table knife). An ice cube placed over the sting reduces the pain. A cream or ointment containing an antihistamine, an anesthetic, a corticosteroid, or a combination of them is often useful. Severe allergic reactions are treated in the hospital with epinephrine, intravenous fluids, and other drugs.

People who are allergic to stings should always carry a preloaded syringe of epinephrine (available by prescription), which helps reverse anaphylactic or allergic reactions. Other stings are treated similarly to bee stings. People who have a history of anaphylactic reactions or a known allergy to insect bites should wear identification, such as a medical alert bracelet.

People who have had a severe allergic reaction to a bee sting sometimes undergo desensitization (allergen immunotherapy—see page 1114), which may help prevent future allergic reactions.

Puss Moth Caterpillar Stings

The venomous puss moth caterpillar (also called the asp) is present in the southern United States. It is teardrop shaped and has long silky hair, making it resemble a tuft of cotton or fur. When a puss moth caterpillar rubs or is pressed against a person’s skin, its venomous hairs are embedded, usually causing severe burning and a rash. Pain usually subsides in about an hour. Occasionally, the reaction is more severe, causing swelling, nausea, and difficulty breathing.

People have gotten relief from puss moth caterpillar stings by putting tape on the site and pulling it off to remove embedded hairs. Use of a baking soda slurry or calamine lotion can be soothing, and an ice pack can ease pain. More severe reactions require immediate medical attention.

Insect Bites

Among the more common biting and sometimes bloodsucking insects in the United States are the following:

Sand flies

Sand flies

Horseflies

Horseflies

Deerflies

Deerflies

Blackflies

Blackflies

Stable flies

Stable flies

Mosquitoes

Mosquitoes

Fleas

Fleas

Lice

Lice

Bedbugs

Bedbugs

Kissing bugs

Kissing bugs

Certain water bugs

Certain water bugs

None is venomous. The bites of these insects may be irritating because of the components of their saliva. Most bites result in nothing more than a small, red, itchy bump. Sometimes, people develop a large sore (ulcer), with swelling and pain. The most severe reactions occur in people who are allergic to the bites or who develop an infection after being bitten. Fleas can cause allergic reactions sometimes without biting.

The bite should be cleaned, and an ointment or cream containing an antihistamine, an anesthetic, a corticosteroid, or a combination may be applied to relieve itching, pain, and inflammation. People with multiple bites can take an antihistamine by mouth. People who are allergic to the bite should seek medical attention immediately or use an emergency allergy kit containing a preloaded syringe of epinephrine.

Tick and Mite Bites

Ticks carry many diseases. For example, deer ticks may carry the bacteria that cause Lyme disease (see page 1165). Other types of ticks may carry the bacteria that cause rickettsial or ehrlichial infections (see page 1202). The bites of pajaroello ticks, which are present in Mexico and the southwestern United States, produce pus-filled blisters that break, leaving open sores that develop scabs.

Mite infestations are common and are responsible for chiggers (an intensely itchy rash caused by mite larvae under the skin), scabies (see page 1312), other itchy rashes, and a number of other disorders. The effects on the tissues around the bite vary in severity.

Tick Paralysis

In North America, some tick species secrete a toxin that causes tick paralysis. A person with tick paralysis feels restless, weak, and irritable. After a few days, a progressive paralysis develops, usually moving up from the legs. The muscles that control breathing also may become paralyzed.

Tick paralysis is cured rapidly by finding and removing the tick or ticks. If breathing is impaired, oxygen therapy or a mechanical ventilator may be needed to assist with breathing.

Treatment

Ticks should be removed as soon as possible. Removal is best accomplished by grasping the tick with curved tweezers as close to the skin as possible and pulling it directly out. The tick’s head, which may not come out with the body, should be removed, because it can cause prolonged inflammation. Most of the folk methods of removing a tick, such as applying alcohol, fingernail polish, or petroleum jelly or using a hot match, are ineffective and may cause the tick to expel infected saliva into the bite site.

Some mite infestations are treated by applying a cream containing permethrin or a solution of lindane. A cream containing a corticosteroid is sometimes used for a few days to reduce itching caused by mite infestations. If permethrin or lindane is used, it is given before the corticosteroid.

Centipede and Millipede Bites

Some of the larger centipedes can inflict a painful bite, causing swelling and redness. Symptoms rarely persist for more than 48 hours. Millipedes do not bite but may secrete a toxin that is irritating, particularly when accidentally rubbed into the eye.

An ice cube placed on a centipede bite usually relieves the pain. Toxic secretions of millipedes should be washed from the skin with large amounts of soap and water. If a skin reaction develops, a corticosteroid cream should be applied. Eye injuries should be flushed with water (irrigated) immediately.

Scorpion Stings

The stings of North American scorpions are rarely serious and usually result in pain, minimal swelling, tenderness, and warmth at the sting site. However, the bark scorpion (Centruroides exilicauda or sculpturatus), which is present in Arizona and New Mexico and on the California side of the Colorado River, has a much more toxic sting. The sting is painful, sometimes causing numbness or tingling in the area around the sting. Serious symptoms are more common in children and include

Abnormal head, eye, and neck movements

Abnormal head, eye, and neck movements

Increased saliva production

Increased saliva production

Sweating

Sweating

Restlessness

Restlessness

Some people develop severe involuntary twitching and jerking of muscles. Breathing may become difficult.

The stings of most North American scorpions require no special treatment. Placing an ice cube on the wound reduces pain. A cream or ointment containing an antihistamine, an anesthetic, a corticosteroid, or a combination of them is often useful.

Centruroides stings that result in serious symptoms may require the use of sedatives, such as midazolam, given intravenously. Centruroides antivenom rapidly relieves symptoms, but it may cause a serious allergic reaction or serum sickness. The antivenom is available only in Arizona. It is given only if symptoms are severe.

In areas of the world where scorpions are more poisonous, such as Turkey, the Middle East, and India, stings are treated with drugs and methods that reduce symptoms and complications. Prazosin, an alpha-adrenergic blocking drug, is sometimes used. Antivenins to specific scorpion venoms are available, but their effectiveness has not been proven.

Marine Animal Stings and Bites

A variety of marine animals sting or bite.

STINGRAYS

Stingrays contain venom in spines located on the back of their tail. Injuries usually occur when a person steps on a stingray while wading in shallow ocean surf. The stingray thrusts its tail spine into the person’s foot or leg, releasing venom. Fragments of the spine’s covering may remain in the wound, increasing the risk of infection.

The wound from a stingray’s spine is usually jagged and bleeds freely. Pain is immediate and severe, gradually diminishing over 6 to 48 hours. Many people with these wounds experience fainting spells, weakness, nausea, and anxiety. Vomiting, diarrhea, sweating, generalized cramps, breathing difficulties, and death are less common.

Treatment

Stingray injuries to an arm or leg should be gently flooded with salt water in an attempt to remove fragments of the tail spine. The spine should be removed only if it is at the skin surface and is not penetrating the neck, chest, or abdomen. Significant bleeding should be slowed by applying direct pressure. In the emergency department, doctors reexamine the wound for fragments of the spine. A tetanus shot may be needed, and the injured arm or leg should be elevated for several days. Some injured people are given antibiotics and may need surgery to close the wound.

JELLYFISH

Jellyfish belong to a group known as Cnidaria. Other Cnidaria include

Sea anemones

Sea anemones

Corals

Corals

Hydroids (such as the Portuguese man-of-war).

Hydroids (such as the Portuguese man-of-war).

Cnidaria have stinging units (nematocysts) on their tentacles. A single tentacle may contain thousands of them. The severity of the sting depends on the type of animal. The sting of most species results in a painful, itchy rash, which may develop into blisters that fill with pus and then rupture. Other symptoms may include weakness, nausea, headache, muscle pain and spasms, runny eyes and nose, excessive sweating, and chest pain that worsens with breathing. Stings from the Portuguese man-of-war (in North America) and the box jellyfish (in Australia in the Indian and South Pacific oceans) have caused death.

Treatment

The first step in treating an injury caused by a jellyfish in the oceans of North America is rinsing with seawater to wash away venom from the skin. Any pieces of tentacles should be removed with tweezers or, after two pairs of gloves are put on, fingers. Vinegar should not be used as a rinse on injuries from the Portuguese man-of-war because it can cause additional venom to be released from nematocysts that have not yet stung (“unfired” nematocysts). In contrast, vinegar should be used for stopping additional “firings” of nematocysts from the more dangerous box jellyfish. Seawater should be used to rinse box jellyfish stings because fresh water will cause additional venom to be released.

For all types of stings, hot water or cold packs, whichever feels better to the person, can help relieve pain. At the slightest sign of breathing problems or altered awareness (including unconsciousness), medical help should be sought immediately.

MOLLUSKS

Mollusks include snails, octopuses, and bivalves (such as clams, oysters, and scallops). A few are venomous. The California cone (Conus californicus) is the only dangerous mollusk in North American waters. Its sting may cause pain, swelling, redness, and numbness in the area of the sting and may be followed by difficulty speaking, blurred vision, paralysis of muscles, respiratory failure, and cardiac arrest. The bites of North American octopuses are rarely serious. However, the bite of the blue-ringed octopus— present in Australian waters—although painless, produces weakness and paralysis that may be fatal.

Cone snails are a rare cause of envenomation among divers and shell collectors in the Indian and Pacific oceans. The snail injects its venom through a harpoon-like tooth when aggressively handled (for example, during shell cleaning or when placed in a pocket). The venom can cause temporary paralysis that is fatal on rare occasions.

Treatment

Cone snail stings can be immersed in warm water. First-aid measures seem to provide little help for injuries from California cone stings and blue-ringed octopus bites. If people with any type of mollusk envenomation develop trouble breathing, immediate medical help should be sought.

SEA URCHINS

Sea urchins are covered with long, sharp, venomcoated spines. Touching or stepping on these spines typically produces a painful puncture wound. The spines commonly break off in the skin and cause chronic pain and inflammation if not removed. Joint and muscle pain and rashes may develop.

Sea urchin spines should be removed immediately. Because vinegar dissolves most sea urchin spines, several vinegar soaks or compresses may be all that is needed to remove spines that have not penetrated deeply. Surgical removal may be required for imbedded spines. Because sea urchin venom is inactivated by heat, soaking the injured body part in hot water often relieves the pain.