Three

The Fertile Island Theory

‘Land will not reveal itself easily or quickly. It must be sought for patiently, over time, by many people, employing a wide range of skills and sensibilities. Discovery is a long, drawn-out process, which can have no final conclusion.’

Ray Ericksen

If Thomas Embling had achieved his aims, Australia might now be teeming with zebra, antelope and buffalo, not to mention herds of quagga and flocks of South American curassow. A close friend of Sir William Stawell, Embling was a politician and an entrepreneur with a reputation for eccentricity and spectacular sideburns. He saw Australia as a vast wilderness waiting to be filled with the best in fauna and flora from around the planet.

Among Embling’s obsessions was a determination to solve the puzzle of the ‘Australian Sahara’ and establish an overland trade route with Asia using camels. An ardent contributor to the newspapers, he wrote in 1858:

Our desert could be crossed in 10 days, north to south, and all we need is to leave in Europe that curse of our race—namely, doing only as our fathers have done, from wearing a black hat and black woollen garments, to trying to cross the desert on a horse.

Embling wasn’t the first man to realise the potential of the camel in Australia. In 1846, a resourceful English grazier by the name of John Ainsworth Horrocks set out from Adelaide with an imposing bull named Harry. ‘I have great hopes,’ he wrote to his sister, ‘the journey suits my temperament as I want a more stirring life.’

Horrocks’ adventure turned out to be a little more stirring than he anticipated. Harry soon revealed his darker side by grabbing one of the expedition goats in his mouth and ‘would have broken his back if a man had not quickly rescued it’. Later that afternoon the camel attacked the cook, biting his head and ‘inflicting two wounds of great length above his temples’. A few days later Horrocks was loading his gun when, ‘the camel gave a lurch to one side, and caught his pack in the cock of my gun, which discharged the barrel I was unloading, the contents of which first took off the middle fingers of my right hand between the second and third joints, and entered my left cheek by my lower jaw, knocking out a row of teeth from my upper jaw’.

As he lay in agony in the wilderness, Horrocks scrawled a note for posterity, apologising to his family and patrons. ‘It is with extreme sorrow I am obliged to terminate the expedition…had it been earlier in the season and my wounds healed up I should have started again.’ The injury turned septic and Horrocks died a few days later—the only explorer to be shot by his own camel.

It was Ambrose Kyte’s offer of £1000 and the renewed public interest in exploring that prompted Thomas Embling to reignite his campaign for the introduction of the camel. At the same time a horse-trader by the name of George Landells was about to set sail for India and was looking for a lucrative return cargo. Landells offered to bring back two dozen camels to be used for exploration or as the basis of a breeding program.

At a public meeting on 31 August 1858, Embling and Stawell announced that Victoria’s chief secretary John O’Shanassy had agreed to finance Landells’ scheme and was also considering funding for the proposed expedition. Importing the camels was seen as a strategic masterstroke. It would give Victoria the decisive advantage over other less adventurous colonies whose explorers continued to lumber around on horses and in bullock carts. Editorial after editorial extolled their virtues. ‘The camel, with a load of five to six hundred pounds upon its back,’ the Argus enthused, ‘will with the greatest facility proceed at a rate of forty or fifty miles, and if necessary, will go without water for a period of from ten to fourteen days…What might not be expected from an exploring party equipped with these ships of the desert?’

The camels had been ordered but the Exploration Committee still had to raise the £2000 necessary to supplement Kyte’s offer. Despite rousing speeches on the value of exploration, most people were too engrossed in their daily lives to care about what lay in the centre of the continent—much less pay for the privilege of finding out.

The Philosophical Institute responded by forming yet another committee, headed by Sir William Stawell. Ostensibly the Exploration Fund Committee was an independent body, yet all but one of its members also served on the Exploration Committee as well. This led to several farcical situations when one body had to ‘resolve’ a contentious issue with the other. At least it made sitting on the fence a little easier. It was, after all, the position of choice for most members of the institute.

The Herald suggested that Victoria should approach South Australia and New South Wales to see if they were interested in ‘a grand combined effort to complete the exploration of this continent’. The South Australians, fearful of losing their monopoly on the overland telegraph, had been openly scathing since the expedition was first suggested. ‘Victoria has hitherto done nothing in the work of exploration,’ scoffed the Register, ‘and with the customary ardour of a neophyte she is now projecting labours which no veteran would willingly undertake.’

New South Wales regarded the plan with a polite lack of interest—as did most of the citizens of Victoria, who between them contributed an average of just £100 per month to the expedition’s coffers. The Exploration Fund Committee meetings fell away from three times to once a week and by December 1858, they stopped altogether. The project seemed unlikely to survive the lethargy of a Melbourne summer, let alone the heat of the Australian desert.

It took the achievements of a diminutive Scotsman in South Australia to rouse the slumbering Victorians. John McDouall Stuart might never have come to Australia had he not been so small that he was rejected for full army service. At 1.67 metres tall and weighing less than sixty kilograms, he was not considered fighting material, and he turned to civil engineering instead.

One of at least eight children, Stuart was born in Dysart, Fifeshire, in 1815, the son of an army captain. He and his siblings spent their early days running wild, exploring the honeycomb of smugglers’ caves that ran through the cliffs near the harbour. When Stuart was just twelve years old this happy childhood was shattered when both his parents died in quick succession. His older brothers went away to study at university and his sisters were sent to boarding school in Edinburgh. Although Stuart was cared for by an old housekeeper in the same city, he rarely saw the rest of his family. From that moment on John McDouall Stuart struck a lonely figure, always an outsider who never managed to re-establish a home of his own. One incident in particular seems to have sealed his destiny.

By 1838, Stuart was living in Glasgow. Early one September evening he was on his way to visit his fiancée at a small cottage on the edge of town. The Scotsman had met the young woman through his friend William Russell—she was Russell’s cousin. Now he had finished his studies as a civil engineer, Stuart wanted to find out if she would be willing to emigrate to Australia with him. Rounding the corner he looked up to see his future wife locked in an embrace with another man. As Stuart stared at the scene in horror, he realised the man was none other than Russell. He turned away and headed for the docks.

Stuart caught a boat to Dundee and secured a passage on the Indus, bound for Australia. He sailed the next day, never realising that William Russell was also due to leave for Adelaide and had called around to see his family on the eve of his departure. The kiss was nothing more than two cousins saying goodbye. (Two years later the young woman wrote to Stuart enclosing her engagement ring and explaining what had happened—but by then the young Scotsman had closed his mind to all thoughts of female companionship or marriage.)

Stuart had always suffered from poor health and the voyage to South Australia did nothing to improve his frail constitution. A fellow passenger recorded that, ‘on the voyage out Mr Stuart was somewhat delicate, having two rather severe attacks of vomiting blood’. (His later symptoms and constant stomach problems suggest that he was suffering from a duodenal ulcer.) Another noted: ‘He was a great reader, comparatively silent, very stubborn, yet withal an agreeable companion, and was rather a favourite amongst his fellow passengers.’

Those who met Stuart after his arrival in South Australia in January 1839 spoke well of him but, still suffering from the pain of his broken engagement, he shunned Adelaide society and headed for the solitude of the bush. He soon found work with a survey team, mapping out plots of land for new settlers. He slept in a makeshift tent, worked six days a week and received a wage of two shillings and ten pence per day plus rations (not including fresh vegetables).

There is a peculiar quality to the Australian bush that permeates the consciousness of anyone patient enough to endure the heat, the dust and the insects, and who can look beyond its initial disguise of pallid uniformity. It is a fascination fuelled by the intense transparent light and the overpowering sense of space. The explorer Ernest Favenc understood this. ‘Repellent as this country is,’ he wrote, ‘there is a wondrous fascination in it, in its strange loneliness, and the hidden mysteries it might contain, that call to the man who has known it, as surely as the sea calls to the sailor.’ So it was with Stuart. Like many explorers he was a social misfit, craving escape from the conventions of society and never comfortable with emotional commitment. Most of his friends were either children or animals and he was so ill at ease staying in the city that he took to sleeping in the garden whenever possible.

In 1844, when Stuart heard that the surveyor-general Charles Sturt was planning an expedition towards the centre of Australia, he jumped at the chance to join the party as a draughtsman. As the gruelling journey towards Cooper Creek took its toll, ‘little Stuart’ surprised everyone with his stamina and resourcefulness. He once saved the party by tracking a flock of pigeons to one of the few remaining waterholes in the area. Then, when the chief surveyor James Poole died from scurvy, Stuart took over, earning high praise from his leader who recorded the ‘valuable and cheerful assistance I received from Mr Stuart, whose zeal and spirits were equally conspicuous, and whose labour at the charts does him great credit’.

The expedition with Charles Sturt cemented the desert landscape in Stuart’s imagination. At a dinner to celebrate its return he told guests:

It might be thought by many present that their journeys through the scorching desert of the North were unrelieved by any agreeable change. This was a mistake. They had all along the pleasure which enlightened men know how to appreciate,of admiring the stupendous works of Nature; and they were ever and anon buoyed by the hope that their explorations would result in an extension of knowledge.

From now until the end of his life, Stuart was to return again and again to the Australian wilderness.

Charles Sturt’s reports of unrelenting misery did not inspire the South Australian government to fund further exploration. Between 1845 and 1858, John McDouall Stuart tried his hand at land speculation and sheep farming but he had little business acumen and most of his ventures ended in failure. It was only when wealthy businessmen James and John Chambers and William Finke hired him to find agricultural land in and around the Flinders Ranges that the Scotsman found his real vocation.

Surveying new grazing runs allowed Stuart to spend most of his time in the bush, which was probably just as well as he had a reputation for ‘intemperance’ whenever he went back to town. Stuart was a classic binge drinker. He could function perfectly well for weeks out in the bush, but as soon as he came within a sniff of a whisky bottle he drank until he dropped. The fourteen-year-old son of one of Stuart’s friends recalled:

Oh, he is such a funny little man, he is always drunk. You won’t be able to have him at your house. Papa couldn’t. Do you know, once, when he got to one of Papa’s stations, on coming off one of his long journeys, he shut himself up in a room, and was drunk for three days.

Away from the bottle, Stuart had an uncanny knack for discovering good pastures in rough country. It was a valuable talent. Many South Australians had disappeared to the Victorian goldfields and only the prospect of rich grazing land would entice them back to rejuvenate the local economy. As well as the paucity of labour, a presumption known as the ‘Fertile Island Theory’ was hampering agricultural development. It predicted that the salt lakes Edward Eyre had found around the north of the state would stifle any further territorial expansion, leaving South Australia isolated and enclosed by an impenetrable natural barricade.

In 1858, Stuart’s patrons Finke and Chambers decided to send their surveyor to disprove the ‘Fertile Island Theory’. Stuart was delighted. It was the perfect opportunity to try out his new tactics for dealing with hostile country. Like Augustus Gregory, Stuart rejected Charles Sturt’s strategy of hauling cumbersome wagons and heavy supplies from camp to camp. He planned to move as fast as possible with just a few horses. It was a risky scheme that could easily backfire in bad conditions but it would allow Stuart’s party to cover more ground and cut down the time they needed to stay out in the desert.

Taking advantage of the cooler weather, Stuart left the settled districts in June 1858 with an assistant, George Foster, and a young Aboriginal guide. The trio rode north towards the salt-lake country through the Flinders Ranges. These soaring red escarpments and cavernous gorges stretch for 300 kilometres, before stopping in a series of sheer rock walls that stand like battlements guarding the desert country beyond. The view from the edge of the bluffs is one of the most arresting in Australia. To the south and east, the giant rock undulations run down like waves until they break gently above Port Augusta. To the north and west, there is nothing but desiccated brown earth running towards a string of sharp white salt lakes on the horizon.

This scorched landscape stretches all the way to Lake Eyre, a salt lake covering around 5800 square kilometres with an annual rainfall of less than 125 millimetres. Surrounded by the Tirari Desert, the area has remained largely immune to the taming influence of fences, roads and homesteads. Travellers through the ages have found it an unsettling environment. The explorer Cecil Madigan wrote in 1940:

There are other barren and silent places, but nowhere else is there such vast, obtrusive, and oppressing deadness. One does not need to understand the past history of the region; the ghostly spirit brooding of the past is inescapable, haunting, menacing. Death seems to stalk the land. The vast plain that is the lake is no longer a lake. It is the ghost of a lake, a horrible, white, and salt-crusted travesty.

Thirst can never be quenched there, it can only be aggravated; eyes are blinded by the flare, throats parched by the bitter dust. All signs of life cease as the dead heart, the lake, is approached. The song dies on the drover’s lips; silence falls on the exploring party. It is like entering a vast tomb. Gaiety is impossible. One fears to break the silence. There is the indefinable feeling of the presence of death.

It takes a certain type of courage to clamber down from the fertile plateau and set out into the haze with just two companions, six horses, a month’s supplies and a compass. Stuart did not hesitate.

He rode north-west across the plains, searching for a mythical freshwater lake referred to by the Aborigines as Wingilpin. The northern settlers told stories of a giant oasis surrounded by gum trees and mobs of kangaroos—there were even rumours that the lost scientist Ludwig Leichhardt had been killed on its shores. Whenever Stuart asked the local tribes where the lake was, they would point in the direction he was heading (whatever that might be) and announce that it was ‘five sleeps’ away.

As the days passed, Stuart began to wonder if the lake was just wishful thinking. With the terrain deteriorating, he complained everything was ‘bleak, barren, and desolate. It grows no timber, so that we scarcely can find sufficient wood to boil our quartpot.’ But his persistence was rewarded by the discovery of a significant watercourse he named Chambers Creek. The party pushed on further through good grazing country and it began to rain. Cracks in the drought-ravaged soil filled with water and overflowed until Stuart found himself ‘on an island before we knew what we were about. We were obliged to seek a higher place. Not content with depriving us of our first worley [shelter], it has now forced us to retreat to a bare hill, without any protection from the weather.’ The next day the floods receded but the horses were still ‘sinking up to their knees in mud’ and at one point the whole party was forced to wade ‘belly deep’ in water. The men made for drier ground and crossed a small range of mountains. On the other side, the whole world turned white.

Stuart had stumbled onto the bleached stony plains that surround the present-day opal mines of Coober Pedy. It is a landscape so alien that it is used as a location for science fiction movies. The town’s name comes from the Arabana Aboriginal term kupa piti, which means ‘white man’s hole’. The miners discovered that the only way to deal with the extreme temperatures was to live underground. Today subterranean homes, churches and shops still exist. Outside there is hardly a blade of grass or a tree to be seen, yet in a few areas nearby sheep are raised with some success. Locals joke that they browse in pairs—one to turn the stone over and the other to lick the moss off the bottom. It is hardly intensive farming. Even in the more fertile areas, it takes twelve hectares to support a single sheep and twenty hectares to support a cow.

As he rode through the bleak landscape, Stuart found that the intense light reflecting back from the white rocks caused constant mirages. They were so powerful, he wrote, ‘that little bushes appear like great gum-trees, which makes it very difficult to judge what is before us; it is almost as bad as travelling in the dark’. With no sign of better country ahead, the explorers were in a precarious position. They had been away for more than two months. Ahead, they faced a scene of terrible desolation. The horses were lame and the scarcity of game meant that their supplies were almost gone. On 16 July 1858 Stuart swung southwards, admitting that he couldn’t ‘face the stones again’.

The retreat came just in time. The men were down to their last loaf of damper when they noticed the first signs of fertility returning to the countryside. Soon they were riding through grass ‘up to the horses’ knees’. Seizing his chance to escape, the Aboriginal guide deserted Stuart and Foster. The ragged pair trudged towards the Nullarbor Plain and once more the countryside degenerated into a ‘dreary, dismal, dreadful desert’. ‘When will it end?’ asked Stuart despairingly in his journal:

For upwards of a month we have been existing upon two pounds and a half of flour-cake daily…Since we commenced the journey, all the animal food we have been able to obtain has been four wallabies, one opossum, one small duck, one pigeon, and latterly a few kangaroo mice, which were very welcome; we were anxious to find more.

It was five agonising days before Stuart spotted some fresh horse tracks in sand, an indication he was nearing the south coast. From an old hand-drawn map, he judged that they would reach water the next day. Twenty kilometres later the men stumbled into Millers Water, near Ceduna on the Great Australian Bight, just as Stuart had predicted. They were safe.

His journey was an outstanding achievement. He had travelled through more than 1600 kilometres of inhospitable territory using only a compass to navigate and he had mapped out thousands of square kilometres of potential sheep country. The total cost of his journey was £10 for food and £28 for his assistant’s wages. The expedition completed Stuart’s rigorous apprenticeship. He had been out with one of Australia’s greatest explorers, he had honed his bush skills through years of surveying and now, he had completed a major journey with the minimum of equipment. More than most European men alive, he had come to terms with the capriciousness of the Australian desert.

Stuart learned that the outback is governed by irregular climatic patterns that last for years, not months. It is the driest region of the driest inhabited continent on earth, yet it can experience more than 180 millimetres of rainfall on a single day. The temperature ranges from minus 5°C on a winter’s night to 45°C on a summer’s afternoon. The sky is filled with an overwhelming intensity of heat and light that can be dissolved by the fury of a violent thunderstorm at a moment’s notice. Like a giant eraser, the wind skittles across the landscape resculpting the sand dunes and obliterating the footprints of all those who have gone before. Gusts of over 110 kilometres an hour pick up the dust and hurl it around, blotting out the sky and churning the air into a writhing mass of grit. Yet Stuart also realised that the desert was a place of surprise and delight. He learned to savour the fragility of the sunrises, the riotous sunsets and the clarity of the heavens lit up each night by the giant white smudge of the Milky Way.

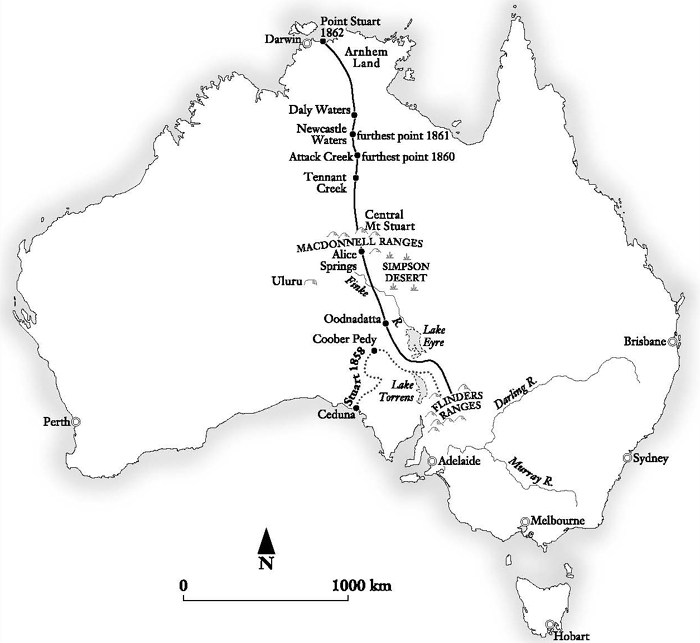

Stuart kept to a similar route on his three attempts to cross the continent. His discovery of mound springs between the Flinders Ranges and Oodnadatta helped him reach central Australia.

Stuart seemed oblivious to the desert’s detrimental effect on his health. As he travelled home from Ceduna to tell his patrons Chambers and Finke of his discoveries, he called in to see his fellow Scotsman, Robert Bruce, the manager of Arkaba Station. Bruce recalled:

I turned to see a pallid pasty-faced looking face, crossed by a heavy moustache, and roofed in with a dirty cabbage tree hat, peering through the rails. ‘You have the advantage of me,’ said I, though the man’s voice sounded very familiar to my ears. ‘Oh, you know me all right, I’m Mr Stuart,’ he responded…’I thought I knew your voice,’ I replied politely, ‘but what have you been doing with yourself? Your voice is all that is left of you.’

To Stuart’s delight, the cattle station had just taken a delivery of whisky. By the end of the evening the normally taciturn Scotsman was boasting about his ancestors from the Royal House of Stuart and delivering rousing versions of ‘Auld Lang Syne’. Even Bruce seemed surprised at the amount of liquor such a small man could consume.

Only the desert was more enticing than the whisky bottle. When Stuart’s hangover subsided, he continued to work for the Chambers brothers. During 1859 he and three men explored around the northern end of Lake Eyre where they discovered a chain of mound springs running for hundreds of kilometres through some of the most barren areas on the continent. These tiny volcano-like structures occur along faults in the earth’s surface. They are formed when water, which once fell as rain over the Great Dividing Range millions of years ago, trickles into a giant underground reservoir known as the Great Artesian Basin. Then it bubbles up through tiny cracks in the earth’s crust at temperatures up to 43°C, forming tiny oases and unique thermal wetlands like Dalhousie Springs on the edge of the Simpson Desert.

This ready supply of fresh water was the key to breaking through the horseshoe of salt lakes that had defeated Edward Eyre. The geological faultline led Stuart to rivers that beckoned towards the interior. Now more than ever he was determined to ‘lift the veil’ that hung over central Australia, and cross the continent from coast to coast.