Five

A Trifle Insane

‘All things considered there are only two kinds of men in the world—those who stay at home and those who do not.’

Rudyard Kipling

In 1854, it was common in the town of Beechworth to see a tall athletic horseman thundering past the weatherboard cottages, sending mud flying in all directions. With his long black beard flowing in the wind and a daredevil glint in his bright blue eyes, he would gallop twenty kilometres to the local magistrate’s house, leap from his horse and swing on the garden gate until he had enraged its owner beyond words. Only then would the police officer ride home, remove his uniform, and retire to a bathtub in his garden. Superintendent Robert O’Hara Burke did not care for the heat.

Newspapers greeted Burke’s appointment with a mixture of relief and incredulity. Most commentators were pleased that a Victorian candidate had triumphed over the ‘foreigners’ but others were baffled. Did the policeman possess any relevant qualifications for the post?

Until recently Burke had been unknown in Melbourne society but, as reporters soon discovered, his past was as intriguing as his current bathing habits. He was born in Ireland in 1820, the second son of a distinguished family of landowners, and he grew up in the privileged surroundings of the St Clerans estate in Galway, cared for by his devoted nurse Ellen Dogherty.

At the age of twenty, Burke chose a military career but he shunned the British forces, opting instead for the predominantly Catholic Austrian army—a highly unorthodox move given the fact he was a Protestant. After securing an introduction to Prince Reuss’s Seventh Hussars through the British ambassador in Vienna, the young Irishman became a cadet in 1842, and by 1847 he had been promoted twice and was posted to Italy. Life in the regiment was tough. The soldiers wintered out in muddy fields, living under canvas in freezing conditions, often with little to do except play cards and keep an eye on the bands of Italian rebels roving the countryside. But the army also had its perks. Once on leave, Burke travelled to the great European cities and, dressed in the braided uniform of his elite regiment, found that doors opened into an altogether more glamorous world.

The young Irishman cultivated a rakish image, indulging himself in the pursuits expected of a young officer: hunting, gambling, dancing, gambling, chasing women and gambling. He acquired a particular reputation as a favourite with the opposite sex and legend has it that he acquired the large scar on his cheek by fighting a sabre duel to defend his honour. Burke was intelligent, musical, well-read, and could flatter anyone he chose in French, Italian and German. With another promotion at the end of 1847, he seemed to be on the brink of a glittering career. Yet just a few months later First Lieutenant Robert O’Hara Burke was facing ruin at the hands of a military court.

As his regiment prepared for action in Sardinia, Burke went absent without leave and set off through Recoaro in northern Italy to the spa towns of Grafenburg and Aachen in Germany. Rumours circulated that he was ill with constipation but it seems more likely that a mountain of gambling debts provided the real incentive to leave.

By the time he returned to his regiment early in 1848, he was facing a court-martial and a possible jail sentence. Fortunately, a preliminary inquiry found he had run up his debts through ‘carelessness’ rather than deceit. Burke was allowed to resign—his punishment was the dishonour of a shattered reputation.

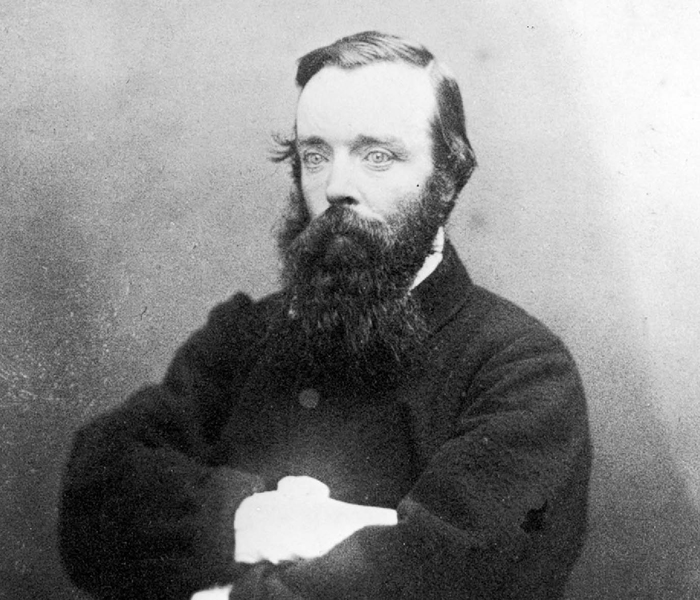

Burke presented this portrait to Julia Matthews whom he first met in 1858, when he proposed to her for the final time.

With his military career over, Burke turned to the police force and joined the Irish Constabulary in County Kildare. He quickly made a name for himself as a ‘powerful young man’ whose ‘great feats as an athlete were the theme and conversation of all who witnessed them’. But Burke found the life of a country policeman monotonous and the salary inadequate—it hardly compared to the excitement and sophistication of Europe.

A transfer to Dublin’s mounted police failed to curb Burke’s restlessness. He hung around in the city’s bars, where stories of gold and adventure in Australia cut through the haze of tobacco smoke and fired his imagination. As a member of the gentry, he was more fortunate than most—family connections gave him strings to pull, and he had no reservations about giving them a sharp tug in order to escape his provincial existence. In time-honoured fashion Burke accumulated an impressive portfolio of references from men who barely knew him, but nevertheless proclaimed he was ‘a man with unusual and extensive knowledge of the world’. Thus armed, he set sail for Australia.

By the time he landed in Melbourne in 1853, Victoria’s gold rush was in full swing and the colony was in desperate need of police officers to impose order on the chaos. So many fortune seekers had arrived that most miners were struggling to make a living. Burke soon realised that gold mining was not the guaranteed route to wealth he had imagined. He fell back into a police career and was made an acting inspector at Beechworth, 260 kilometres north-east of Melbourne.

The position was not an easy one. When Burke arrived it was the administrative centre of the Ovens Valley region, which was dominated by the gold-mining industry. Crime was rife and ethnic disagreements between the European and Chinese immigrants promoted a simmering sense of unease in the valleys. Bushrangers menaced the highways, cattle rustlers stalked the plains and petty thieves harassed the shopkeepers. The pubs were crawling with diggers drowning their sorrows or picking fights. On a good evening, they might even manage both. It was a district that became famous for hardened criminals—the Kelly gang was to terrorise the area in the late 1870s until Ned Kelly was caught and committed for trial at the Beechworth courthouse.

For now, Acting Inspector Burke was preoccupied with reforming his demoralised officers, who spent most of their time extracting bribes from the local ruffians and drinking the proceeds at one of the sly-grog shops in the area. He was also left to deal with endless petty offences such as ‘riding furiously while intoxicated’ and ‘public drunkenness’.

As the local police chief Burke was also the town prosecutor. Given the number of magistrates who reprimanded him for his inattention to detail and propensity to lose important paperwork, it was a role he obviously found irksome. In fact life in Australia was proving to be depressingly similar to the one he had left behind in Ireland. The only compensation was the salary. At £700 a year, it was three times what he would have made back home.

Away from the bright lights of Europe, Burke ceased to maintain his dashing image. Despite his rank, Burke did not appear to possess a full police uniform and he was known to rush around borrowing clothing from his colleagues whenever a local dignitary was due in town. On or off duty, he didn’t care what he looked like, and was often seen wearing check trousers, a red shirt and a threadbare jacket covered in patches. Underneath a peculiar sombrero-type hat, his hair was unkempt and his face obscured by a black beard, over which he was sometimes said to dribble saliva.

But the real gossip centred on Burke’s bathing habits. Neighbours whispered he was ‘as fond of water as a retriever’, and that he often spent hours lying in his outdoor bathtub, wearing nothing but his police helmet, reading a book and cursing the mosquitoes. In the heat of summer the local constables were startled to find their inspector stretched out in the water working on his police reports. In order not to embarrass his housekeeper, Burke constructed a screen with a trapdoor in it so that food and drink could be passed to him as he reclined. Several people wondered if he was perhaps ‘a trifle insane’. Burke did nothing to counter the impression. Once he tired of administration, he would leap from his bath and indulge in frenetic bouts of exercise—taking long walks in the forest by himself or setting about the local trees with an axe. At least he undertook these activities fully clothed.

Despite this behaviour Burke proved himself a popular and capable police chief. He had a knack for imposing strict discipline yet remaining friendly with his subordinates. While improving the efficiency of the Beechworth force, Burke still found time to share stories and jokes with the locals and became famous for his extravagant tales of adventure in Europe. He took an active part in town life, joining the local orchestra and helping to establish a Literary and Science Institute. He was so well-liked that, when he later applied for a transfer to the town of Castlemaine, the residents of Beechworth petitioned him to stay on.

Whatever freedom Burke had to indulge his eccentricities in the Australian bush, the tedious life of a country policeman failed to satisfy his aspirations for adventure. He told colleagues that he was desperate for ‘something to take the sting out of him’.

Then, in 1854, Burke’s younger brother James became the first British officer to be killed in the Crimean war. His heroic death was reported in the Age:

As he leapt ashore, six soldiers charged him. Two he shot with his revolver, one he cut down with his sword, the rest turned and fled. Then he had charged a group of riflemen with headlong gallantry. As he got near he was struck by a ball, which broke his jawbone, but he rushed on, shot three men dead at close quarters with his revolver, and cleft two men through helmet and all into the brain with his sword. He was then surrounded and while engaged in cutting his way with heroic courage through the ranks of the enemy, a sabre cut from behind, given by a dragoon as he went by, nearly severed his head from his body; and he fell dead, covered with bayonet wounds, sabre gashes, and marked with lance thrusts and bullet holes.

Burke was profoundly affected by this glorious (if exaggerated) account and could often be found staring at his brother’s portrait and weeping. The tragedy continued to weigh on his mind, for in March 1856 he obtained leave of absence and left to join the British army. He arrived in Liverpool to find his services were not required. The fighting was over and a peace treaty had already been signed.

Disappointed, Burke returned to Australia and by the end of 1856 he was back in his old position at Beechworth where he found life just as mundane as before. With the gold now beginning to run out, the only real excitement was a riot staged by European and American miners who set about trying to drive their Chinese counterparts away from the diggings. At gunpoint, they herded their Asian neighbours like sheep until some fell down a gorge into the Buckland River. When Burke heard of the trouble, he took twenty men and rode the eighty kilometres to Buckland in just twenty-four hours. As they neared the scene, there was talk of an ambush but Burke refused to turn back. Placing himself in front of his men, he charged into the miners’ camp—only to find it deserted. The unrest was over. Just as he had missed the height of the gold rush and the fighting in the Crimea, Burke turned up at Buckland a little too late to take part in the real action. It seemed he had a talent for bad timing.

It wasn’t until 1858, when a travelling theatre company came to town, that life began to liven up in Beechworth. Its star performer was a sixteen-year-old actress described by the critics as ‘sparkling, gay and bewitching’. Julia Matthews was born in London, the daughter of a music teacher and a sailor turned artificial-flower maker. Their daughter was precociously talented and made her debut in Sydney in 1854 in a play aptly named Spoiled Child. She had been entrancing audiences ever since.

As a music and theatre lover, it was no surprise that Burke went to see Julia perform, and even less of a surprise that he fell uncontrollably in love with her. Each evening his passion increased as he sat transfixed in the front row. On her last night he went backstage and asked her to marry him. Even by Burke’s standards, it was an outrageous proposal. He was a thirty-eight-year-old Protestant police officer and she was a Catholic actress less than half his age (actresses in those days being considered of dubious reputation however scrupulous their conduct).

Julia Matthews was a seductive actress and singer who captivated Burke until he was prepared to risk everything to win her love.

The offer horrified Julia’s mother, who saw Burke as yet another ‘Stage Door Johnnie’. Her daughter was already earning the vast sum of £60 per week (of which Julia received just 2s 6d) and Mrs Matthews envisaged a long and lucrative career, not an early wedding to a country police officer. But her opposition could not deter this lovestruck Irishman. On the ingenious pretext of tracking a gang of dangerous horse thieves, Burke spent the next few weeks charging around Victoria to watch his beloved’s every performance. Julia may have been susceptible, but all the Irish charm in the world could not persuade her mother, who took her daughter back to Melbourne to star in a new opera. Burke had no option but to return to his lonely life of bachelorhood in Beechworth.

In the weeks that followed, neighbours noticed that his cottage was filled with music. He had bought a piano and was playing out his grief through Julia’s songs. Later, when the heartbroken policeman remembered that his next-door neighbour was expecting a baby, he worried that his constant practising might be disturbing the family. He gathered up as many blankets as he could and draped them over the piano to dampen the noise, then continued playing the same songs for hours on end. When the baby was delivered, Burke told the proud father, with tears in his eyes: ‘Ah, if I had such ties as you have, I think I should be a happier and better man.’

The Irishman’s life had stalled. In November 1858, he transferred to the larger Castlemaine district, where along with two hundred others from the town, he subscribed two shillings and sixpence to the ‘Exploration Fund’—little knowing that one day he would be leading the expedition. In the meantime, he fell in with a new group of friends including the town jailer John Castieau.

Castieau’s boisterous diary of life in Castlemaine reveals a long series of rowdy parties and poker games often conducted ‘at my friend Burke’s house’. On Sundays, the two men would set out for walks in the countryside to clear their heads, before Burke began to grumble that the journey was too arduous or the weather too hot and insist that they retire instead to the pub for lunch. On one occasion they conducted running races in the beer garden with Castieau reporting later, ‘Came home and was so sick I could eat no dinner, my racing days are over!’

The opportunity to escape presented itself with the arrival in Castlemaine of a railway tycoon named John Bruce. Like Ambrose Kyte, Bruce was a businessman of dubious methods. He often used the local police to quell disturbances staged by his disgruntled workers and, in the course of his dealings with Burke, was impressed by his ‘manliness of character and determined energy’. The two men became friends and it wasn’t long before Bruce began to smarten up his protégé and introduce him to the ‘right people’ in Melbourne. When the Royal Society announced it was looking for an expedition leader, Bruce encouraged Burke to apply.

It was a tantalising prospect and Bruce made it seem all the more attractive by embellishing the endeavour with stories of fame, glory, knighthoods and grants of land. In fact few explorers ever received much financial reward for their efforts. Only one, the irascible Sir Thomas Mitchell, received a knighthood and that was only to keep him quiet. But for a disillusioned policeman desperate for an opportunity to distinguish himself, this was the chance to fulfil all his dreams. After all, what woman could resist an offer of marriage from a rich and famous explorer?

The idea of Burke leading any expedition anywhere at all was ludicrous. He was neither a surveyor nor a scientist and had no exploration experience. His talent for getting lost was legendary, prompting his bank manager, Falconer Larkworthy, to observe:

It was said of him as a good joke but true nevertheless, that when he was returning from Yackandandah to Beechworth he lost his way, although the track was well beaten and frequented, and did not arrive at his destination for many hours after he was due. He was in no sense a bushman.

Beechworth’s police officers often had to retrieve their chief from ‘his latest confusion’ and the Mount Alexander Mail revealed, ‘he could not tell the north from the south in broad daylight, and the Southern Cross as a guide was a never ending puzzle to him’. How would he cope in the wilderness with no roads or signposts? How could he travel in a straight line when he couldn’t even measure latitude and longitude?

There was also a question mark over Burke’s temperament. He had energy and passion in abundance, but was such an exuberant daredevil the right man to lead a large party of men into unknown territory? Did he have the tenacity of Charles Sturt, the methodical persistence of Augustus Gregory or the eye for detail of Ludwig Leichhardt?

Exploration might seem a glamorous occupation, but it was often a laborious test of stamina and organisation. Burke was popular, charming and intelligent but excitable, impulsive and headstrong. He responded to situations emotionally and seemed to lack the composure to think through the consequences of his actions.

So why was such an unlikely candidate chosen to lead the most prestigious project Victoria had ever undertaken? The answers lie buried deep in the preoccupations of a colonial society convinced of its own superiority, and in the Machiavellian motivations of a small group of rich and powerful men who were developing a strong influence on the expedition.

The higher echelons of Melbourne society had been weaned on a diet of British class-consciousness. Many commentators accepted Burke’s appointment because he came from an ancient and honourable family and was ‘accustomed to command’. Never mind that he could hardly read a compass—he had the right blood flowing through his veins and as far as the Herald was concerned that was enough:

We may add here that a brother of Mr Burke’s, an officer in the Royal Engineers, made himself very conspicuous for his gallantry at the beginning of the Crimean War and is celebrated in Russell’s history of the campaign. Such is the man, his qualification and his antecedents. That these are such as will induce public confidence in Mr Burke there cannot, we think be any doubt.

One reporter was impressed with Burke’s physical attributes. ‘He was tall, well-made with dark brown hair; his broad chest was decorated with a magnificent beard; he had fine intelligent eyes, and a splendidly formed head’. Another described him as ‘a gentleman in the prime of life’ who was ‘a perfect centaur as to horsemanship’. Then, there was Burke’s dashing history and his mysterious scar, all of which proved immensely appealing to the ladies of Melbourne. The chief justice’s wife Mary Stawell gushed:

When we first met Mr Burke we called him ‘Brian Boru’; there was such a daring reckless look about him which was enhanced by a giant scar across his face, caused by a sabre cut in a duel when he was in the Austrian service; he had withal a very attractive manner.

In 1859 Burke had joined the Melbourne Club, allowing him access to the rich and powerful. He quaffed red wine with men like Sir William Stawell, who was as impressed by Burke as his wife had been, and would become a strong advocate.

As the leadership battle dragged on through April and May of 1860, Gustav von Tempsky embarked on a rigorous training program, improving his cardiovascular capabilities and poring over astronomical formulae. Burke took a rather different approach. He was normally to be found in the bar of the Melbourne Club losing vast quantities of money at cards but winning plenty of friends. At times his debts reached up to £450—nearly two-thirds of his annual salary.

As Burke’s losses mounted, John Bruce and his associates manipulated matters shamelessly in the background, leaning on friends, calling in favours, even conspiring to stack the Exploration Committee with members sympathetic to the cause.

John Macadam, secretary of the Royal Society, was influential in the leadership battle to ensure Burke’s victory.

Their most important conquest was Sir William Stawell. Once he had indicated his support for his fellow Irishman, several committee members including Georg Neumayer and John Macadam followed suit.

Burke’s cosmopolitan past was also proving a powerful asset. He hailed from Galway so he identified with the Irish contingent, and his fluent German went some way to mollifying the scientists on the committee. Best of all, he was not South Australian. Despite his lilting accent and his Irish ancestry, Burke’s seven years’ service in the colony made him as Victorian as the next man.

Burke enjoyed every minute in the limelight. Perhaps in his more romantic moments he imagined himself like the knights of old—he had been given a quest, a chance to prove himself and perhaps to secure the woman he loved. In the meantime he set about reversing the effects of his somewhat dissolute leadership campaign. Reports began to appear in the newspapers of a red-faced man jogging around Melbourne’s Royal Park. It was Burke, tackling ‘the severest of physical privations’ to ready himself for the journey ahead.

On 4 July 1860 a ragtag assortment of prospective explorers queued outside the headquarters of the Royal Society. Seven hundred men applied to join a venture that would ‘constitute for long years if not ages to come, the highest glory of the colony of Victoria’. Many men offered to go for minimal wages; some said they would go for none at all.

Their applications ranged from grubby scrawled notes to an eleven-page dossier detailing supplies, equipment, possible routes and probable dangers. Many of the letters were from stockmen and drovers who boasted of their capacity to work for days without food, ride the wildest of horses, shoot the wariest of kangaroos and ‘deal’ with the ‘most difficult Aborigines’. One typical applicant, Edward Wooldridge, claimed to be ready for every hardship:

I’ve often cooked my own dinner at the end of a pointed stick promoted for the occasion to the office of toasting fork. It may be suggested to an explorer that the very food itself is often wanting; be it so in such a case, my stomach would doubtless grumble but I would endeavor to bear the privation with equanimity.

Wooldridge needn’t have bothered. The inspection process was a charade. Burke spent just three hours looking at three hundred of the applicants then dismissed them all in favour of men with the ‘right’ connections. He ignored candidates like Robert Bowman and William Weddell, both of whom had travelled through the Australian deserts with Augustus Gregory and had excellent references from their former employer.

Twenty-five-year-old William Brahe was chosen largely because his brother was a friend of Georg Neumayer. Since arriving in Australia in 1852, the young German had worked on the Victorian goldfields, where he was well known for his skill in driving wagons on the muddy roads. John Macadam recommended sailor Henry Creber as a useful man in case an inland sea was discovered. Robert Fletcher’s father was a friend of several committee members. Blacksmith William Patten and labourer Thomas McDonough knew Burke back in Ireland, Patrick Langan met him in Castlemaine and Owen Cowan was a fellow Victorian police officer.

Once the men had been chosen, the Exploration Committee decided that the expedition should leave by the end of August 1860. But with just a month to go before departure its route had still not been finalised. It had been assumed that Burke’s party would leave from Melbourne and make for the north coast via Cooper Creek, but at a meeting on 17 July 1860, events took an extraordinary turn.

It emerged that some committee members favoured a bizarre scheme to load the camels back onto the Chinsurah and sail them halfway round Australia to an inlet known as Blunder Bay on the north-west coast. The expedition would then traverse the continent southwards to Melbourne. The plan was endorsed by George Landells, who was suspected of plotting with the Chinsurah’s owners to split the profits from the voyage. Burke also spoke in favour of the Blunder Bay option and in the absence of Sir William Stawell, who favoured Cooper Creek, the Exploration Committee agreed to support the new route.

When Stawell awoke the next morning to find the headline ‘To Blunder Bay’, plastered all over the newspapers, he was furious. The chief justice immediately called another meeting and, in a withering address, insisted the resolution should be overturned. As usual, he got his way. On 27 July, an announcement was made that Burke would leave from Melbourne. The Exploration Committee issued Burke’s official instructions, which started clearly enough:

The Committee having decided upon ‘Coopers Creek’ of Sturt, as the basis of your operations, request that you will proceed thither, form a depot of provisions and stores, and make arrangements for keeping open a communication in your rear to the Darling, if in your opinion advisable; and thence to Melbourne, so that you may be enabled to keep the Committee informed of your movements, and receive in return the assistance in stores and advice in which you may stand in need.

After that, however, the orders became vague and confused:

The object of the Committee in directing you to Cooper’s Creek, is, that you should explore the country intervening between it and Leichhardt’s track, south of the Gulf of Carpentaria, avoiding, as far as practicable, Sturt’s route to the west, and Gregory’s, down the Victoria to the east.

To this object the Committee wishes you to devote your energies in the first instance, but should you determine the impracticability of this route you are desired to turn westward into the country recently discovered by Stuart, and connect his furthest point northward with Gregory’s furthest Southern Exploration in 1856 (Mount Wilson)…

Should you fail, however, in connecting the two points of Stuart’s and Gregory’s furthest, or should you ascertain that his space has already been traversed, you are requested if possible to connect your explorations with those of the younger Gregory in the vicinity of Mount Gould, and thence you might proceed to Shark’s Bay, or down the River Murchison to the settlements in Western Australia.

The instructions effectively allowed Burke to go wherever he chose. The next paragraph admitted as much:

The Committee is fully aware of the difficulty of the country you are called on to traverse, and in giving you these instructions has placed these routes before you more as an indication of what is deemed desirable to have accomplished than as indicating any exact course for you to pursue.

These baffling orders only reinforced the growing sentiment that the Exploration Committee was not capable of organising a Sunday picnic. The rumours surrounding Burke’s appointment had intensified until he was forced to defend himself, insisting he had used ‘only fair and honourable means’ to secure his position. But the Age still suspected the public was not being told the whole story:

If Mr B’s scientific attainments are equal to the task, let the public know them, if they are not, the public will protest against a piece of cliqueism in which the interests of the country are again sacrificed to please and serve the purposes of an unscrupulous and dangerous party.

Some columnists predicted that the expedition would be a disaster. One forecast that lives would be lost.