Twelve

Anticipation of Horrors

‘If there is such a thing as darkness which can be felt, then the Australian desert possesses a silence which can be heard, so much does it oppress the intruder into these solitudes.’

Ernest Favenc

Without William Wills, we would have almost no record of the first European crossing of Australia. To begin with, the surveyor maintained his diary scrupulously, leaving a detailed if somewhat clinical journal that bears all the hallmarks of his rationalist beliefs. Later, as the trek began to take its toll, dates become muddled and days get lost in the battle for survival. The original volumes survive to this day—they include a set of scientific records, consisting of up to fifteen meteorological readings a day, followed by pages of long-winded navigational calculations.

Overland navigation in 1860 was a laborious business. Sir Thomas Mitchell (or rather his servants) carried a sextant that weighed twenty-four kilograms. In addition, a typical surveyor needed compasses, a telescope, a chronometer, a theodolite, and special measuring chains the length of a cricket pitch known as ‘Gunter chains’. Wills travelled light. His most useful tool was a prismatic compass. The surveyor set his course, then kept to it as far as the terrain allowed. Some areas were littered with rocky outcrops, rivers or boggy country, which meant detours and recalculations. Other patches of open desert were so devoid of reference points that the party stuck as best they could to a predetermined bearing for days on end with nothing to aim for except the dreamlike world of the mirages hovering above the horizon.

In order to compile a proper map, Wills also had to calculate the distance travelled each day. The most accurate methods were time-consuming. Some surveyors used a measuring wheel, others laid out their 20.1-metre Gunter chains end to end. Wills guessed his speed for a fixed distance and then extrapolated from that figure.

Latitude, the party’s north-south position, was established by measuring the sun’s altitude using a sextant and a pool of mercury enclosed in a vibration-proof box to create an artificial horizon. Wills looked through a system of lenses until he saw dual images of the sun reflected in a mirror. He then moved an index arm on the sextant until the two suns became superimposed and read off an angle from the instrument’s scale. Several pairs of readings were necessary to make an accurate calculation and, despite years of practice, Wills found it a tricky process. ‘In windy weather,’ he complained, ‘it is seldom possible to keep the mirror free from dust even for a few seconds and this so interferes with the readings of the spirit level that the altitudes taken with this horizon cannot be depended on within one minute of arc.’ Once altitude readings had been obtained, Wills used a special set of tables known as a nautical almanac to calculate his latitude.

Longitude, the party’s east-west position, was established by comparing the local time with the time at a fixed point such as the Greenwich meridian. Since the earth revolves fifteen degrees every hour, if Wills knew the difference between the two times, he could then calculate his longitude. In order to ascertain the local time, the surveyor used his sextant to determine when the sun reached its highest point. This method was dependent on the accuracy of his chronometers, and in the 1860s it was a tall order to expect a watch to function without error throughout the rigours of a desert expedition. Indeed, it was not uncommon for variations of several degrees to creep in over a number of months.

As Charles Sturt and John McDouall Stuart had discovered to their cost, taking sun sightings in the desert was a painful process that ruined their eyesight. For most of the journey Wills avoided the problem because he was also proficient at taking star sightings, and even seemed to prefer the nocturnal method. If the night sky was clear he would spend at least an hour and a half working out the altitude and position of selected stars. Then, using his astronomical tables, he could calculate his latitude and his longitude without having to ‘shoot the sun’.

In contrast to Wills’ meticulous records, Burke’s entire ‘diary’ consists of no more than 850 words. Even the barely educated John King kept a better record than his leader. Burke’s efforts are contained in a leather-bound pocketbook, which is still smudged with red earth. It contains an inscription on the first page: ‘Think well before giving an answer, and never speak except from strong convictions.’ The rest of the entries comprise little more than a scrappy list of dates and campsites scrawled in pencil on random pages throughout the book.

The first few notes read:

16th December Left depot 65, followed by the creek.

17th The same.

18th The same. 67

19th We made a small creek, supposed to be Otta Era (?), or in the immediate neighbourhood of it. Good water. Camp 69.

20th Made a creek where we found a great many natives; they presented us with fish, and offered us their women. Camp 70.

21st.—Made another creek: Camp 71. Splendid water; fine feed for the camels; would be a very good place for a station. Since we have left Cooper’s Creek, we have travelled over a very fine sheep-grazing country, well-watered, and in every respect well suited for occupation.

22nd December 1860.—Camp 72. Encamped on the borders of the desert.

23rd December 1860.—Travelled day and night, and encamped in the night in the bed of a creek, as we supposed were near water.

Burke had always disliked paperwork. Visitors to his Beechworth home were shocked to discover the walls were plastered with scraps of paper containing scribbled messages in English, French and German. A sign read: ‘You are requested not to read anything on these walls, I cannot keep any record in a systematic manner, so I jot things down like this.’

By nineteenth-century standards, Burke’s diary is particularly disappointing. Sometimes expedition journals were works of literature in their own right commanding sizeable advances from publishers. They were also of great commercial and political interest with enormous consequences for investment, infrastructure and population growth. The Exploration Committee had asked Burke to keep a detailed record of his journey, but in the end impatience overruled obligation. Burke would sometimes read Wills’ journal and make suggestions but that was all. It is a pity. He may have provided a livelier, more personal record than his surveyor.

Once they left Depot Camp 65, Burke, Wills, Gray and King found the first few days of the journey almost idyllic. Predictions of desiccated wastelands and aggressive Aboriginal warriors came to nothing as they led their camels through the shade of the gum trees alongside the Cooper. Even when they turned north, away from the benevolent influence of the creek, Wills was delighted to find that between the sand dunes, the valleys were ‘very pretty…and covered with fresh plants, which made them look beautifully green’. If anything the ground was too wet rather than too dry, and the confusion of boggy gullies made setting a course and walking in a straight line a luxury.

William Brahe accompanied the party for the first day. The next morning, 17 December, Burke reiterated his belief that William Wright would be ‘up in a few days’, even instructing his new officer to catch him up with any messages if his back-up arrived soon. With this reassurance ringing in his ears, Brahe turned his horse around and headed back to camp. His only function now was to survive and await his leader’s return. Neither he nor Burke had any idea of the extraordinary events taking place in Menindee, a few hundred kilometres to the south.

On 19 December, Hermann Beckler was checking the supplies of dried meat at the camp on the Darling when a ragged emaciated figure stumbled into view. ‘His face was sunken,’ the doctor recalled, ‘his tottering legs could hardly carry him, his feet were raw, his voice hoarse and whispering. He was a shadow of a man. He laid himself at my feet and looked at me wistfully and soulfully.’

It was Dick the Aboriginal tracker. He had left Trooper Lyons and Alexander MacPherson at Torowoto—home to the Wanjiwalku people. All the horses were lost or dead and the two white men were so weak they were unable to travel. Dick had walked alone for a week to save his companions. He had eaten just two birds and a couple of lizards during his 300-kilometre journey.

Contradicting Burke’s accusation that he was too scared to leave the settled districts, Beckler offered to mount a rescue mission. Dick was in no condition to assist, so the doctor took Belooch and another Aboriginal guide named Peter. They set out with three camels and a horse, pushing themselves as hard as they could to reach Lyons and MacPherson. Despite the crisis, Beckler was effusive about the surreal beauty of Australia’s desert country:

Nothing could disturb us from the sensual ecstasy of this day, neither the worry about the success of our journey north, the continually oppressive heat, nor even the extremely unpleasant behaviour of our animals…Parts of the chain of hills before us seemed to be reflected on expansive surfaces of water whose edges the eye could never determine. Here and there vertical lines cut through the wavelike contours of the chain of hills; once again everything seemed to blur into a blueish haze. To the east, the ghostly shapes of gigantic treetops, towering over sheets of water, appeared to form the entrance to a fairy land. What could be more natural than that this unexpected mirage should intensify the magic of this land, a land we have never seen, that we entered as the first Europeans, a fata morgana, the gateway to terra incognita!

Providing the only permanent water for many kilometres, the rock pools at Mutawintji attract emus, kangaroos, euros and yellow-footed wallabies. Ludwig Becker was enchanted by them.

Guided by Peter, the doctor followed Burke’s old track towards Mutawintji, where he delighted in the Aboriginal art he found around the cool rocky overhangs:

The walls and ceilings were covered with the impressions of outstretched human hands in the most varied colours, a decoration, which had something ghostly about it at first sight. These impressions were such that the hand with its extended fingers appeared in the natural grey or yellow-grey of the rock, while their very sharp outline was formed by a halo of colour which gradually disappeared around the outside and which looked as though it had been sprayed on…Later I was informed by a native that the artist held a solution of colour in his mouth and sprayed it over his or another’s hand, which was held spread out over the rock. These people paint with their mouths, and their oral cavity also forms their palette.

After a week of hard travelling, it was Beckler who spotted Alexander MacPherson: ‘He raised himself laboriously from a stooped position in which he seemed to be gathering something from the ground. He staggered towards us. For several minutes he was completely speechless, but finally he cried out, “Oh Doctor!”, and tears streamed from his eyes.’ Lyons was not far away. He was in better shape physically but seemed resigned to his fate in the desert and ‘had to be cheered up constantly by the others so that he did not despair completely’. Both men had lived for two weeks under an old horse blanket. They had scratched themselves raw from the mosquitoes.

MacPherson told Beckler they had suffered constantly from diarrhoea and vomiting as they tried to head north from Torowoto, and once their horses died, they had no choice but to retreat. Sometimes they were so thirsty they ‘rinsed out theirmouths with their own urine, and derived great relief from it’. It had taken all their strength to return to the waterholes, where Dick negotiated with the local Aborigines to bring them food, while he returned to Menindee to fetch help. For a few days they received birds, snakes and the odd goanna before the local hunters moved on and they were reduced to gathering the local nardoo plants to grind into flour.

It would have been sensible for Beckler’s rescue party to head back to Menindee all together, but by this time the doctor was thoroughly carried away with his new role as an explorer. He decided to strike out for the nearby Goningberri Ranges with Peter, leaving the other three to walk back by themselves. The trio then argued over the choice of route and Belooch walked off by himself. Quite by chance, Beckler found him five days later wandering in circles, delirious and almost dead from thirst. It was another lesson (if one was needed) that dividing up parties in such treacherous country was not a good idea.

In all, the Lyons debacle had been nothing but a dangerous waste of time. Three men had nearly died, four horses were gone and Wright had lost more valuable time—it was now two and a half months since Burke had left Menindee.

After Brahe departed a new routine settled over Burke’s party. Between 4 and 5 a.m., as the sun rose, the men would crawl from their bedrolls, shake the insects from their blankets and turn their boots upside down to check for scorpions. As Charley Gray began the packing, John King set out to retrieve the camels. He led them back to the camp, selected a soft level piece of ground, and ordered them to ‘hush down’. The animals roared and groaned as they rocked backwards and forwards, then dropped down on their haunches into the sand.

The camel is not a creature designed for freight. The hump means that cargo inevitably slides downhill and it is essential that the load is well distributed and securely anchored. An unbalanced pack results in saddle sores and abscesses, followed by flies, infections and maggot infestations. The average pack camel can carry around 200 kilograms for fifty kilometres a day. More weight means less distance. Pushing an animal too hard results in a severe deterioration in condition and ultimately, premature death.

In the cool morning air, King adjusted each pack before enlisting the others to help him hoist it aboard. Then he prepared the riding camels, fitting a bridle and an Indian-style saddle, which is placed on the back with the hump protruding through the middle. Stirrups could be fitted if necessary and there was plenty of room to suspend water bottles, rifles, oilskins, binoculars and other assorted paraphernalia.

When everything was ready, King joined the animals together via their nose-pegs (since camels chew cud continuously, they cannot be fitted with a bit and bridle like a horse) and then cajoled them into line ready for the day’s work. Accompanied by another chorus of bellowing and cursing, the expedition moved off.

The party tried to cover as much ground as possible before the sun took hold, so breakfast was postponed until mid-morning. Burke or Wills marched ahead carrying the compass followed by Gray leading Billy, and King bringing up the rear. Camels walk best in a particular order. Just one intractable animal can cause havoc, tripping up the others and breaking their rhythm. King soon learnt which camels to put where, and they loped along comfortably, taking just one stride for every three human steps.

After marching for two or three hours the men stopped for a meal of salted meat, damper and tea. If they were lucky, they might find a scrubby tree or a bush to provide a metre or two of shade, though often they squatted down behind the camels to shelter from the sun. Sometimes the explorers pulled off their boots, inspected their blisters and settled down for a snooze, but they soon realised that the longer the break, the harder it was to get going again. After a few days, they confined themselves to just a few minutes’ rest. Burke took all the major decisions regarding route and pace, but it was Wills who determined their course and plotted their position.

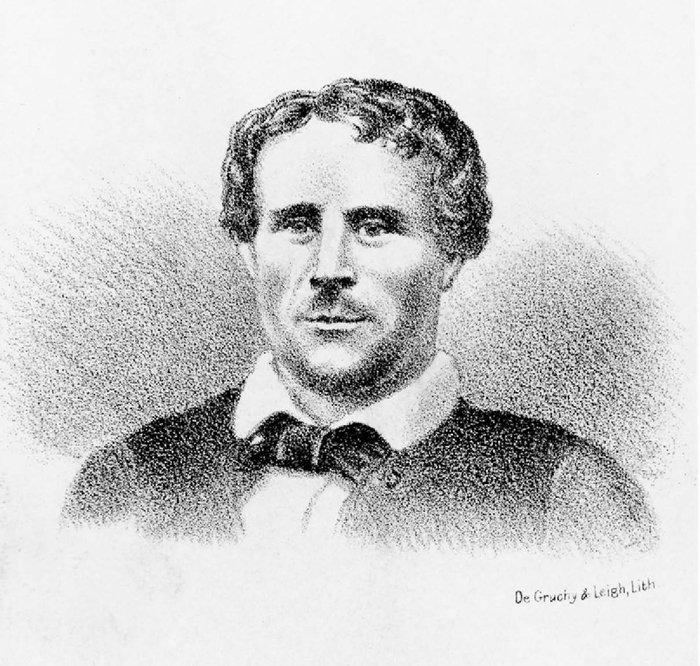

John King’s health problems made him an unlikely candidate to cross Australia, but his expertise in handling the camels won him a place in Burke’s final party.

As the temperatures increased, the party would rest in the middle of the day and then travel late into the evening, continuing by moonlight if conditions allowed. Campsites were selected for their proximity to water, firewood, shade and good feed for the animals. The camels nibbled at nearly anything but their favourite food was a succulent plant known as parakeelya and Wills mentions that they were often able to camp in areas with an abundant supply. After a hard day’s work, the camel’s favourite relaxation was to sink down for a roll in a patch of soft sand. Unlike Landells, King only released them in hobbles. After Wills’ experience losing the animals near the Cooper, everyone was careful not to let the animals stray too far.

Without tents or tonnes of equipment, camps were quickly established. Within minutes of halting, King was tending the animals and Gray was collecting wood for the campfire. It was his job to prepare the evening meal and bake the damper for the next day’s journey. Once these tasks were complete, there was always equipment to mend, packs to reorganise and sores to bathe—no one relaxed for very long. With darkness falling, the cicadas revved up for their evening performance. Their rasping calls throbbed through the campsite as the men fell upon their suppers with relish. Most nights, while supplies were plentiful, they ate a sort of stew made with salt beef, poured over rice and bread, and finished off with a cup of tea and sugar.

It is unclear how much Burke contributed to the running of the camp. As leader, he was not expected to perform menial jobs, but with such a reduced party it seems unlikely that he did nothing at all. Wills was always busy, taking meteorological observations, writing up his journal, and completing his scientific records. After supper, the bedrolls were laid out, the campfire was stoked up to ward off the mosquitoes and each man lapsed into his own thoughts.

With the flames flickering beneath the gum trees, the desert shrank. For a few brief hours the toil was over—a warm glow of security suffused the camp and shut out the vastness beyond. Only the eerie howl of the dingo reminded them of the world outside. Burke seemed unconcerned about the threat of attack by the local Aborigines. No one kept guard at night. Only Wills stayed awake. The surveyor moved away into the gloom to take star sightings and finish his navigational calculations. He was the only one of the party to go to bed at night with any idea where they were.

There was one important task that had to be completed each day. In order to tame the ‘pathless wilds’, the Exploration Committee had asked Burke to mark his route ‘as permanently as possible, by leaving records, sowing seeds, building cairns at as many points as possible’. The expedition leader was careless about such obligations but, every evening, King took a knife and hacked away the bark of a tree to engrave the letter ‘B’, followed by the camp number. Once the tracks of the horses and camels were washed away, these small engravings became the only evidence of the first European journey across Australia.

Since 1860, many Burke and Wills enthusiasts have souvenired these carvings or marked trees of their own, leading to confusion about the precise position of authentic expedition camps. There are two ways to spot a ‘fake’ Burke and Wills tree. The explorers never carved ‘BW’ (it was Burke’s expedition and Wills was only recognised later on) and they always inscribed the camp number in roman numerals because straight lines are easier to carve.

The dynamics of this small group were finely balanced. Each man was dependent on the skills of the others, so personal quirks and weaknesses stood out. In practical terms, Wills was a more capable leader than Burke, but the Irishman possessed a combination of dash and charisma that either infuriated or inspired. The two men were complete opposites in most respects, yet they developed a relationship of ‘affectionate intimacy’, with Burke habitually referring to his deputy as ‘My dear boy’. As the days passed, the four men seemed to settle down well and the journey north was free of the hostility that had torn the expedition apart on the way to Menindee. In particular, twenty-two-year-old John King was distinguishing himself as a versatile and capable member of the party. Small, quiet and shy, he was an unlikely explorer.

John King grew up during the years of the Great Famine in a thatched whitewashed cottage in the village of Moy, County Tyrone. To ensure he escaped a life of poverty his father (himself a soldier) enrolled him at the Royal Hibernian School, a military college in Dublin. At the age of fourteen King found himself a member of the British army. In his neat handwriting he wrote down his particulars in his regimental account book:

Height: 5 feet 1 inches

Hair: Brown

Complexion: Fresh

Eyes: Hazel

Next of kin: William and Samuel King (brothers, 70th regiment)

Date of birth: December 15th 1838

A year later King was posted to India, where he joined the military band and then took a posting as a teacher, attached to the 70th infantry regiment. In 1857, he was stationed in Peshawar at the height of the Indian Mutiny. A fellow soldier described one example of the brutality that occurred when groups of rebels were brought into the barracks:

The forty men condemned to death were brought out in batches of ten and were placed with their backs against the muzzles of field guns. No word of command was given by the officer of the artillery detachment, but the gunners knew that when he raised his sword arm they were to fire. This was done to save the men who were to be shot from hearing the word of command. I think this form of death was much more merciful than the alternative of either hanging or shooting, the charge of the blank powder in the gun instantaneously breaking the body into some four pieces. This process was repeated until the whole of the number had been executed.

King was among the lines of soldiers watching this grisly punishment and shuddered with revulsion each time the blast of the cannons shattered another body in front of him. Soon afterwards he went on leave for sixteen months after contracting ‘fever of a bad type’, a complaint that was probably exacerbated by the initial stages of consumption. King was convalescing in Karachi in 1859 when he met George Landells. The camel trader was impressed with the young man’s ability to speak the various languages of the sepoy camel handlers, and it wasn’t long before he suggested that King sign up for a grand expedition across Australia. It was the perfect excuse to leave the army. King purchased his discharge and joined Landells on the trek through India to take the camels back to Australia. By the time they reached Melbourne, Landells was more convinced than ever of King’s worth and persuaded Burke to hire him at a salary of £120 per year.

During the power struggle that erupted on the way to Menindee, King might have been expected to sympathise with Landells, but there was never any hint of him taking sides or incurring Burke’s wrath. Always calm and reserved, with a strong sense of duty, King melted into the background and got on with his job. His reward was a place in the forward party.

With King in charge of the camels, the rest of the camp work fell to ex-sailor Charley Gray. A tall bear-like man in his forties, his employer Thomas Dick described him as a ‘stout and hearty’ worker, who got drunk just once a month when he received his wages. With his cheerful grin and easy-going personality, Gray was a favourite at the pub in Swan Hill, where he worked as an ostler, and he seemed to get on well with everyone on the expedition. Now, with his sinewy arms covered in tattoos of mermaids and anchors, Gray was about to embark on the first overland crossing of Australia.

In the first week the expedition averaged around twenty-five kilometres a day. Wills was pleased to report on 23 December that so far, the journey had been relatively painless:

We found the ground not nearly so bad for travelling on as that between Bulloo and Cooper’s Creek; in fact, I do not know whether it arose from our exaggerated anticipation of horrors or not, but we thought it far from bad travelling ground and as to pasture, it is only the actually stony ground that is bare, and many a sheep run is in fact, worse grazing than that.

Charley Gray was well-liked and had proven bush skills. The controversy that later surrounded him led to intense scrutiny of Burke’s behaviour.

Burke and his men were doing well. As the terrain grew harsher, they displayed an uncanny ability to discover the most fertile strips of land, in areas where just a kilometre either way might make the difference between finding water or dying of thirst. Their first stroke of good fortune was to traverse an area 100 kilometres above the Cooper, known as Coongie Lakes.

These magical lagoons lie nestled amongst brick-red sand dunes. Nourished by an almost permanent supply of milky orange water, the lakes form one of the richest ecological sites in Australia, providing sanctuary to people, animals and plants. They are important to many Aboriginal groups but principally to the Yawarrawarrka people, who know the area as Kayityirru. When Burke and Wills stumbled across Coongie, it was in pristine condition—before the influx of rabbits and cattle ravaged the soil and dislocated the trees. They saw it before the wide dirt roads of the oil and gas prospectors crept ever closer and the thump of the seismic equipment echoed through the soil. Even now, with pipelines and mines sneaking through the dunes, Coongie retains its tranquillity and magnificence. It is a remote area, often cut off for months by floodwaters, but anyone persistent enough to come here is rewarded with the sense of entering into an enchanted kingdom, insulated from the rest of the world by a sea of rippling sand. Wills was delighted to find such fertile country:

At two miles further we came in sight of a large lagoon bearing N by W, and at three miles more we camped on what would seem the same creek as last night, near where it enters the lagoon. The latter is of great extent, and contains a large quantity of water, which swarms with wildfowl of every description. It is shallow, but is surrounded by the most pleasing woodland scenery, and everything in the vicinity looks fresh and green. The creek near its junction with the lagoon containing some good water-holes some five to six foot deep.

Coongie’s Aboriginal inhabitants were astounded by the strangers who set up camp at their waterholes, but they expressed neither fear nor hostility. Wills found the local people to be remarkably welcoming:

There was a large camp of not less than forty of fifty blacks near where we stopped. They brought us presents of fish, for which we gave them some beads and matches. These fish we found to be a most valuable addition to our rations. They were the same kind as we had found elsewhere, but finer, being nine to ten inches long, and two or three inches deep, and in such good condition that they might have been fried in their own fat.

Later, both Burke and Wills mention that the local tribesmen offered them women, according to their custom. These invitations were rejected in disgust.

So far Wills had proved to be somewhat condescending towards Aboriginal behaviour and traditions. Burke’s attitude ranged from indifference to hostility. Now the journey was under way, he wanted to travel across the continent with as little interference as possible. Most of the time he did just that. Wills was often surprised that they didn’t see more Aborigines, unaware that the party was being constantly monitored by a network of well-camouflaged messengers. The camels and Billy meant the expedition was never molested. Speed also helped. Since the party never lingered for more than a night at each campsite, it was not seen as a threat. Indeed, the local people often overcame their shyness to point out the best creeks and waterholes to the men as they passed through.

On several occasions Burke and Wills tried to persuade Aboriginal men to guide them, although they did not resort to the brutal tactics of later explorers such as David Carnegie. He would often hunt and capture Aboriginal people, then tie them to a tree until thirst forced them to point the way to the nearest billabong. Wills offered beads and mirrors as enticements but there was no time to win anyone’s trust and his attempts failed.

On Christmas Eve, nearly 200 kilometres from the Cooper, they reached a campsite Wills described as their most beautiful so far:

We took a day of rest on Gray’s Creek, to celebrate Christmas. This was doubly pleasant, as we had never in our most sanguine moments anticipated finding such a beautiful oasis in the desert. Our camp was really an agreeable place for we had all the advantages of food and water attending a position on a large creek or river, and were at the same time free of the annoyances of the numberless ants, flies and mosquitoes that are invariably met with amongst timber or heavy scrub.

The men rested by the creek and indulged in extra rations. Burke planned to catch up on his diary but perhaps his Christmas feast got the better of him. He managed just forty-two words: ‘We started from Cooper’s Creek, Camp 66, with the intention of going through to Eyre’s Creek without water. Loaded with 800 pints of water, four riding camels 130 pints each, horse 150, two pack camels 50 each, and five pints each man.’ One can easily imagine Burke asleep under a gum tree, his cabbage-tree hat over his face to keep out the flies and his notebook lying in the dirt beside him.

The party left Gray’s Creek at 4 a.m. on Christmas Day, but lethargy soon overtook them. Burke recorded: ‘At two pm, Golah Singh [a camel] gave some very decided hints about stopping and lying down under the trees. Splendid prospect.’ Every hour of rest was a luxury. The party was still travelling too slowly and using up too much food. The journey was degenerating into a test of endurance—as much a race against dwindling rations as against McDouall Stuart. Burke’s diary declined further into a series of dates and times:

December 30th—Started at seven o’clock; travelled 11 hours.

31st—Started 2.20; 16½ hours on the road. Travelled 13½ hours.

1st January 1861.—Water.

2nd January.—From Kings Creek; 11 hours on the road. Started at seven; travelled nine and a half hours. Desert.

3rd January.—Five started. Travelled 12 hours. No minutes.

4th.—Twelve hours on the road.

The terrain was unpredictable. There were stretches of easy walking across drying claypans and lightly timbered plains, but there were also large tracts of boggy ground and kilometres of monotonous red dunes. Even so, the horrors of Sturt’s Stony Desert were never fully realised. The simmering rubble appeared only in patches, leaving Wills sceptical of their fearsome reputation: ‘We camped at the foot of a sand-ridge jutting out on to the stony desert. I was disappointed although not altogether surprised that the latter was nothing more than the stony rises we had met with before, only on a larger scale and not quite as undulating.’ The camels coped better on the rugged sections than expected. They possessed a surprising ability to pick their way through the stones, while the men were limited to stumbling along, never quite hitting their stride on the rock-strewn plains.

Twelve hours’ march through the desert soon becomes a tiring and tedious experience. In the desiccated atmosphere, hair becomes brittle, skin burns and flakes, nails crack between scaly cuticles, hands and feet split open and cuts fester into ulcers that never heal. Streams of sweat mix with the sand and dust to produce a gritty paste that chafes like sandpaper in the elbows and groin. Constant wind and intense light leave eyes sore and throats scratchy, reducing voices to a whisper. Sleep is often interrupted by a raspy cough. Flies swarm around the face, provoking a constant swishing motion with the arms and an occasional outburst of total frustration.

The sun heats up the environment until the air, the sand and the rock radiate heat, putting the explorers under enormous physical strain. As their work rate increased, their core body temperatures rose from 37°C to around 39°C. They sweated profusely and their skins flushed as their blood vessels dilated and carried the heat to the surface. At the start of the journey, before they were acclimatised, the men would have been susceptible to salt depletion and cramps. If they worked too hard their heads began to pound and they felt dizzy. Disturbed vision and stomach cramps followed. The only solution to this was to slow down.

Sweating requires energy and large amounts of liquid. Dehydration was a constant danger, especially as it was easy to ignore. The body does not always send the right signals to the brain and many people do not feel thirsty even when they are seriously dehydrated. In severe conditions, when a person sweats up to two litres per hour, it becomes almost impossible for the gut to absorb enough water to keep up. The explorers compounded the problem by marching for many hours without drinking, then guzzling large amounts of liquid in one go once they had stopped. This was the worst way to rehydrate. Since their blood had been diverted away from the gut, their digestive systems couldn’t cope and they felt bloated and sick.

Burke and his men carried about three and a half litres with them per day, yet they would have needed at least fifteen litres just to replenish the liquid they were sweating away. Although they always had sufficient water each evening, they must have been dangerously thirsty throughout most of the day’s march. Dehydration also has a devastating effect on the body’s physical performance. A 2 per cent deficiency in body liquid results in a 10 per cent reduction in endurance capacity. Many of the body’s most important functions including the efficient digestion of food depend on a plentiful supply of water. In their dehydrated state, Burke, Wills, Gray and King were not even getting the full benefit of their limited diet. The explorers were pushing their bodies to the limit day after day. It was an extraordinary demonstration of stamina and determination but the cumulative effects were inescapable.

Mentally, such journeys are just as testing. When trekking hour after hour, it is the small things that irritate. Seeds from tangles of spinifex grass work their way inside socks and boots, irritating the skin until there is no alternative but to spend every rest-stop picking out the burrs and scratching the itchy red sores. Sweat stings, flies buzz, belts pinch, boots rub and water bottles jangle. Just the sound of someone humming a tune over and over or swishing a stick in the sand can be the final straw. Keeping a sense of perspective while marching becomes a conjuring trick of the mind and people have to find their own way of coping.

Burke and Wills were stoic about their physical circumstances. By now they were sometimes achieving sixty kilometres in a single march. If anything, the relative ease with which they coped during the early stages of the journey belied the magnitude of the task ahead. For now, luck was running in Burke’s favour. It was Christmas, and the explorers were about to receive a geographical gift that would take them all the way to the Gulf of Carpentaria.