My first memory was of human hands upon me, helping to pull me free of my mother’s body. It was night, and a low moon hung round and pale in the clear dark sky. For a moment I lay there blinking upon the sand, not knowing who or what I was or what was happening.

“Praise Allah, the foal is alive,” a human voice said as the hands left me.

“Never mind the foal,” another voice called out from very close by. It belonged to a tall man with a bristly black beard and weather-beaten skin that told of many years beneath the desert sun. The harsh, anxious sound of his voice made my ears twitch, even though I didn’t understand what the words meant. “Something is wrong. Sarab is bleeding too much!”

“Are you sure?” a third voice said. “It was a difficult foaling.…”

There was movement, fabric swishing past me as more humans came to bend over the mare lying still on the sand.

I blinked my eyes, swiveling my ears around. There was so much to see and hear that it was difficult to focus. The sky overhead was dark except for the bright moon and a dusting of stars. A breeze tickled the whiskers of my muzzle, and the air felt cool though the sand beneath my body was warm. Nearby stood a large tent made of camel hide, and I could smell and hear other animals moving around on the far side of a grove of palm trees. I wanted to react to all of it, but I didn’t know what to do first.

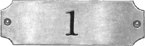

Then a human girl kneeled down in front of me, blocking my view of all else. Her hands reached for me, stroking my face and neck. She had a light touch, like wind through an oasis, and her dark eyes were large and kind.

“It’s a filly, Father,” the girl called out in a voice filled with wonder. “She’s perfect!”

“Keep her out of the way, Safiya.” The older man’s voice still sounded harsh. “Sarab is in trouble.”

Safiya looked toward the mare. “Is she going to be all right?”

“I don’t know. It is for Allah to decide now.”

The girl stayed where she was, crouched over me. Her eyes turned back to mine, ignoring the commotion going on near the mare.

“It’s all right, little one,” she whispered, stroking the dampness out of my fuzzy foal coat. “Your mama is going to be all right. Allah wouldn’t let anything happen to Father’s favorite war mare.”

I still didn’t understand the words. But the girl’s voice sounded uncertain. That made me curious enough to stretch my long neck forward until I could snuffle her face, seeking the scent of her. The girl laughed and pushed my nose gently away.

Another man rushed past, younger than the others and with a lighter beard. Sand flew up from beneath his running feet and pinged against my hide. That made me raise my head and snort in surprise. The effort of doing so tipped me over onto my side.

But I quickly righted myself. That was when I noticed a pair of long legs folded beneath my body. Could they belong to me?

Oh yes! They twitched, and I suddenly understood what they were meant for. Lurching forward onto my sternum, I flung my forelegs out and then scrambled upward.

“Oh! She’s trying to stand already!” Safiya exclaimed. She cried out as I swayed and fell back to the sand.

But I was already trying again. This time I remembered to organize my hind legs as well. A second later, I was standing!

I let out a nicker of triumph. The girl reached out to steady me as I stood swaying there, all four legs splayed in different directions. I leaned against her for a moment, grateful for the help.

The other humans weren’t paying any attention to me. There were four or five of them, all bent over the horse still lying on the sand: my dam. Her sides were heaving, her black coat slick with sweat. I couldn’t see much else of her. Then someone moved, his pale robes swirling out of the way, and I finally saw my dam’s face. She had a fine, chiseled head with a jagged blaze running down it. Her large eyes were rolling and staring. Her nostrils flared with each labored breath.

I knew I wanted to get closer to her. To do that, I had to figure out how to move. My legs trembled, seeming to know what to do. I took a wobbly step forward, nearly falling again.

“Keep her away!” one of the men barked out.

Young Safiya put gentle hands on my neck and shoulder. “Stay back, little one,” she said. “They’re trying to help your mama.”

But there was to be no help for my dam. A few minutes later, her eyes closed. Her graceful neck went limp on the sand. And the tall, bearded man let out a heartbroken cry that echoed across the desert.

“I’m sorry, Father,” one of the younger men said. “Sarab was a fine mare. But at least you still have her daughter.”

“Yes.” Another man stepped toward me for a closer look. “And look, Nasr, she has her dam’s fine head and long legs. Sarab will live on in this one.”

“That’s right, Father,” Safiya put in. “Isn’t she beautiful?”

But her father, Nasr, did not turn toward me. “I do not wish to look upon the foal that took Sarab’s life,” he said, his voice shaking with emotion. “Find it a nurse mare and leave me alone.”

He kneeled down beside Sarab’s body as the other humans exchanged glances. I understood none of what was happening, though I could sense that their faces and voices were troubled.

But I was troubled by something else. Hunger. Now that I was up and moving around, I felt my belly begin to grumble. Instinct told me that I needed to find food soon. But where?

I turned and nudged at Safiya, seeking any sign of something to fill my belly. She patted me and pushed me away, so I turned to the next closest human, one of the younger men. When I nosed at his robes, he glanced down at me.

“The filly needs milk,” he said. “Shall we see if Jumanah will accept her?”

“That’s a good idea,” another said. “Jumanah is a strong, stout mare and always has plenty of milk. And her colt is only a few days old.”

“Yes, the filly can share his mother, or have her all to herself for all I care,” someone else added. “What need have we of another colt?”

“Hush, brother,” the first man said. “All horses are gifts from Allah. We can use the colt as a pack animal when he’s older, or use him for breeding if he is worthy, or perhaps trade him away for something we need. When last we parted from our cousin Rami and his family, they were complaining that several of their horses are getting too old to carry much weight during their moves. I’m sure they’d be glad to trade us a few sheep for a strong, stout, tall colt like that one.”

The other man shrugged. “You’re right, but this filly is much more valuable than any colt, especially if she grows up to be a great war mare like her dam.” He shot a look toward Nasr, who was still bent over Sarab’s body. “No matter what Father might think of her right now.”

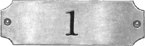

The first man hurried off into the darkness, returning moments later with two horses walking behind him. One was a foal not much older than I was, a tall chestnut colt. But I paid little attention to him. My nose twitched as I caught the scent of the other horse, a flea-bitten gray mare with a robust build and a calm expression.

I let out a cry of eagerness and leaped toward her, almost toppling over. Several strong hands caught me and guided me toward the mare, while one of the men took hold of the colt and kept him away, though he nickered and kept trying to get close enough to sniff at me.

The mare, Jumanah, didn’t object as I found the place to nurse. Soon I was drinking eagerly, my short tail flapping back and forth in time to my suckling. Jumanah turned and smelled me carefully, then nuzzled kindly at my flank.

“That’s a relief,” someone observed as the humans all watched me drink. “At least this little orphan will have a chance now with Jumanah looking after her.”

“Don’t call her an orphan,” Safiya said with a frown.

“Why not?” the youngest of the men said with a shrug. I would later learn he was one of Safiya’s brothers. “That’s what she is, and there’s no shame in it.”

And so I had my name. From that moment onward, the humans referred to me as Yatimah, which means orphan in their language. Jumanah accepted me as her own; just as the humans had hoped, she had milk and attention enough for both me and her own colt, Tawil. And I was content with that, for I knew no different.