The Second World War

The Second World War was the largest naval war Canada has ever fought. Battles raged off its coast, and the government supported the growth of an enormous navy as part of Canada’s war effort. By 1945, the Royal Canadian Navy possessed more than four hundred armed vessels ranging from motor torpedo boats to heavy cruisers, with plans to acquire an aircraft carrier and squadrons of aircraft. The main focus of the navy’s efforts lay in the Battle of the Atlantic: the struggle to secure the North Atlantic trade routes against enemy attack. Much of this effort was carried out by small escort vessels used to defend convoys of merchant ships from preying submarines.

New Brunswick’s important, if modest, role in the war at sea from 1939 to 1945 has been neglected. Naval activity was naturally concentrated at the great naval base of Halifax and at the secondary bases developed at Sydney and St. John’s, Newfoundland. No naval operational bases were established in New Brunswick during the war, although German spies and escaped prisoners of war found New Brunswick’s extensive shoreline useful for their purposes.

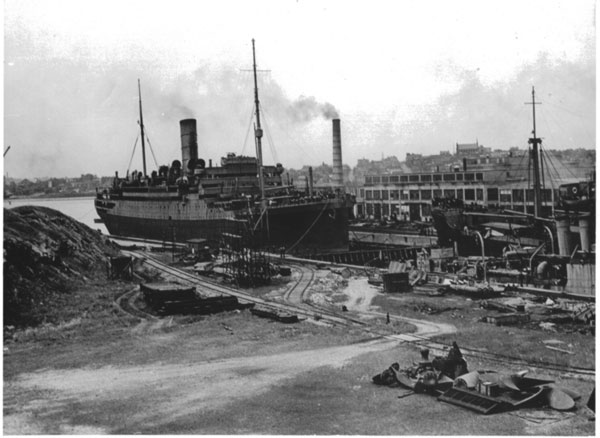

The most important naval activity took place in Saint John, which was still one of Canada’s busiest ports. Established there was the Naval Control of Shipping, which would develop to oversee shipping throughout the waters of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and parts of Quebec. The port was also a crucial refit base for large vessels, including troop transports, cruisers, and battleships. The refit business kept the port’s shipbuilders busy enough, so that little new construction took place after the first contracts were let in 1940 for a new class of patrol vessels dubbed “corvettes.”

Paul Barbour Cross, R.C.N.V.R., commander of the Saint John naval reserve unit for thirteen years prior to 1939 and one of the founding members of the naval establishment in Saint John (H.M.C.S. Captor II) when the Second World War started. Although old for sea service, Cross went on to command the corvette H.M.C.S. Rosthern in the North Atlantic and was awarded the O.B.E. in 1946. http://www.unithistories.com/officers/RCNVR_officers.html

Even before war was declared, the possibility of a future Allied blockade of Europe, the threat of unrestricted submarine attacks on merchant shipping, and the importance of Saint John as a commercial port had led to the establishment of another naval presence in New Brunswick. On August 31, Captain J.E.W. Oland, D.S.C., R.C.N., Ret’d, arrived from Vancouver to assume the post of naval officer in charge of the port. He was joined within hours by Commander P.B. Cross, R.C.N.V.R., and a small staff from Halifax. Cross was no stranger to Saint John, having commanded H.M.C.S. Brunswicker, the newly renamed Saint John volunteer reserve unit, for the previous thirteen years. Routing, cipher work, and intelligence reporting started on September 1, while the balance of the staff arrived the following weekend. And so the basic structure for controlling movements into and out of Saint John was in place and working even as Germany launched its invasion of Poland. Saint John was also the dedicated “Contraband Control Station” for all shipping from the western hemisphere bound for Europe. Ships hoping to pass through the Allied blockade into German-controlled ports had first to stop in Saint John to have their cargoes and paperwork checked to ensure they were not destined for Germany and that they were not carrying such contraband as munitions. By the time Canada declared war on September 10, Saint John had been “at war” for nearly two weeks.

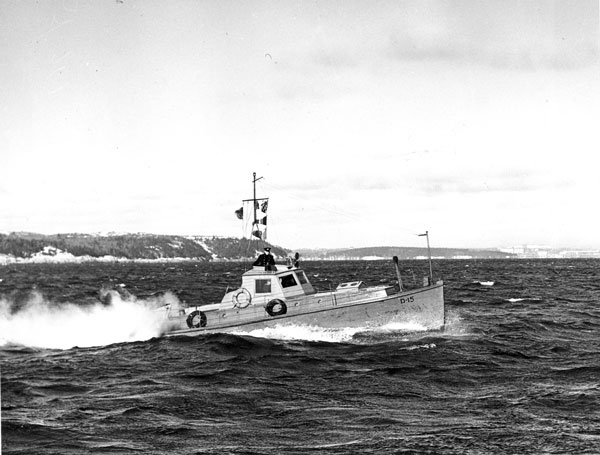

Captain Oland established his office at 250 Prince William Street and immediately acquired the services of three small ex-R.C.M.P. patrol boats and their crews. Vigil II, already in Saint John, was quickly transferred to the R.C.A.F.1 for service as a crash boat. Captor and Acadian (renamed Invader) arrived from Halifax on September 5 and put in operation from Pier 5 at Lower Cove. An examination anchorage was established southwest of Partridge Island where ships could be stopped and their identities checked before proceeding into the harbour. Captor and Invader began examination services on September 19 and were supported after September 25 by an examination battery of two 6-inch guns manned by the army. These guns originally came from H.M.C.S. Niobe, the R.C.N.’s first warship, and had been part of Saint John’s defences during the Great War (both guns can still be seen in Saint John: one at H.M.C.S. Brunswicker, the other at the New Brunswick Museum building on Douglas Avenue). Several times during the war, a vessel that refused to stop for examination or acted strangely received a warning shot across her bow from the examination battery. Once cleared, the ships were allowed into the harbour itself.

Probably the most inelegant depot ship in Canadian naval history, Dredge No. 2, commissioned as H.M.C.S. Captor II in fall 1939. DND Photo

Several other key elements of the Saint John naval establishment were added in September 1939. A site for the Port War Signal Station (P.W.S.S.) — the primary point of communication between the port and its shipping traffic and both the N.C.S. side and the harbour defences — was surveyed at Mispec Point. Until construction was completed in early 1941, however, the navy maintained P.W.S.S. staff on Partridge Island. Accommodation for ships’ crews was acquired on September 26, when the old Dredge No. 1 was taken over and commissioned as H.M.C.S. Captor II. In keeping with the naval custom that all establishments were commissioned “ships,” Captor II served as the depot for the naval establishment in the port, and gave Saint John’s naval base its name.

When Captor and Invader were found too small for regular and reliable duty in the examination anchorage, the ocean-going tugs Murray Stewart and Ste-Anne were acquired, arriving for duty in mid-October. That allowed Captor and Invader to concentrate on inner harbour security patrols, which they did for the balance of the war. The final layer of defences — a patrol force for the outer reaches of the harbour — was temporarily filled in January 1940 when H.M.C.S. Cartier, a former hydrographic survey vessel fitted with one 4-inch gun and four depth charges, arrived to patrol the bay. In the event, Saint John never had its own proper naval forces, although groups of armed patrol and escort vessels operated from the port periodically during the war.

The primary task of Captain Oland’s establishment was to control shipping in and out of the port. Saint John was Canada’s busiest year-around east coast port, and it possessed much more alongside-berthing and cargo-handling capacity than either Halifax or Sydney. But its work fluctuated with the seasons. While the St. Lawrence River was free of ice, much of Canada’s commercial traffic moved in and out of Montreal. Between November and May, however, the bulk of that activity, including many longshoremen, moved to Saint John. Oland’s first report, submitted on February 29, 1940, listed 1,187 vessels that had entered the port since September 1, 1939. Most of these were local coastal and fishing vessels, but the examination service boarded 299 foreign ships and Oland’s N.C.S. staff routed 197 steamers either independently to their overseas destinations or — in the case of seventy-three ships — to Halifax for transatlantic convoys. The examination service was so busy in late 1939 that four additional vessels had to be pressed into service to handle the traffic.

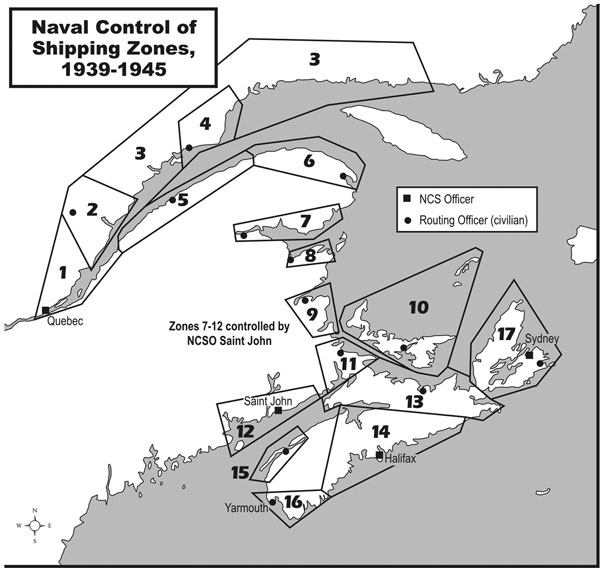

Control and routing of shipping remained H.M.C.S. Captor II’s primary wartime task. This involved close liaison with other local N.C.S. centres at Halifax and Quebec City and with the regional N.C.S. centre in Ottawa. The regional centre in Ottawa was responsible for control of shipping in North American waters — the Caribbean was controlled from Jamaica — and was linked to other regional centres and to the main British Empire and Commonwealth N.C.S. establishment in London. These centres and staffs worked closely with naval intelligence and operational authorities to find safe routes for shipping based on the latest information on enemy and Allied operations. The whole objective was to avoid the enemy, and N.C.S. staff provided merchant captains a prescribed route to follow. Knowing precisely where merchant ships were — and when they were due to arrive at their destinations — also allowed Allied operational authorities to sort out enemy raiders from regular merchant traffic and, if ships failed to arrive, to determine where enemy forces were operating. It was very much like modern air traffic control. As part of this process, N.C.S. staff issued the confidential books and special publications merchant skippers needed to travel safely under wartime conditions.

In January 1940, Captor II also became responsible for the use of the port by “defensively equipped merchant ships” (D.E.M.S.), commercial vessels modified with defensive equipment ranging from guns to armour plating around the bridge, barrage balloons, anti-mine equipment, and small arms. Thirty-seven D.E.M.S. inspections were done that first month and the work remained unrelenting during the war. In the early years, much of the D.E.M.S. work was focused on the large liners that called at Saint John to refit in the port’s dry dock — the largest in the British Empire. Its users included not only fast troop carriers, but also smaller liners that had been converted into armed merchant cruisers. The most famous of these to call at Saint John in 1940 was H.M.S. Jervis Bay, which underwent a refit in July and August. She was sunk the following November by the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer while valiantly defending convoy HX 84 east of Newfoundland. The Jervis Bay Branch of the Royal Canadian Legion and a monument at Ross Memorial Park commemorate her association with the city.

By the end of February 1940, Captain Oland’s staff in Saint John consisted of ten officers, one hundred and nineteen men, and three civilians. They were kept busy through early 1940 as the weight of winter shipping fell heavily on the port: sixty foreign vessels routed in March, fifty-four in April. The coming of spring did not ease the work. In April, Germany invaded Denmark and Norway, and in May the Low Countries and France. Ships from all these countries scattered widely, seeking refuge, replenishment, and repair. The St. Lawrence opened in late April, but the volume of shipping using Saint John remained high. The examination battery had to stop a couple of these ships by firing blank charges.

In May 1940, the work of the Saint John N.C.S. staff was expanded to include ports along the whole New Brunswick coast and the Bay of Chaleur coast of Quebec. Much of this work was done by local customs agents and by posting naval officers to Shediac, Chatham, Bathurst, and Campbellton. Forty-one vessels were routed from these ports in July, most to Halifax and Sydney for convoys.

In May 1940, plans were also announced that the St. John Drydock and Shipbuilding Company would commence constructing a new class of naval vessels at its yards on Courtney Bay. The navy wanted fifty-four of these new patrol vessels based on a whale-catcher design acquired from Britain in 1939. At 200 feet long, displacing 950 tons, powered by familiar steam-reciprocating engines, built to mercantile standards, with a simple armament of one 4-inch Great War-vintage gun and depth charges, and fitted with minesweeping gear, these new patrol vessels would be jacks of all trades and masters of none. They were ordered to give defended ports like Saint John the rudimentary ships they needed to fulfill their function and to trade with Britain for proper warships, such as destroyers. The first three contracts for these vessels, PVs 1, 2, and 3, were let in Saint John, and work commenced on the first two in May.

The next month, Oland reported that work on PV 1 was progressing but that PV 2 was delayed by the arrival of the armed merchant cruiser H.M.S. Laconia, which needed urgent repairs — indeed, it was this unrelenting demand on Saint John as a major repair yard that caused subsequent contracts for new ships to be let elsewhere. As a result, these patrol vessels became the last warships ordered in New Brunswick during the war. These Flower class corvettes — as they were later known, after the name of the first of their kind — would become the iconic escort of the Battle of the Atlantic, the ships that laid the foundation of the modern Canadian navy.

By summer 1940, Saint John had settled into a routine. Murray Stewart and the newly arrived Zoarces operated the examination service, alternating four days on station and four off (in the winter they switched to three and three); both vessels remained in that service until the end of the war. Cartier continued her patrols of the bay, while Captor and Invader conducted harbour patrols. D.E.M.S. personnel worked on large liners and armed merchant cruisers calling at the dockyard, while the N.C.S. staff controlled the movement of vessels throughout the province and along the southern shore of the Gaspé Peninsula.

In August, the examination vessels helped calibrate new 7.5-inch guns at the Mispec Point counter-bombardment battery, and approval was received to establish a War Watch Station at Tiner’s Point. Tenders for the Port War Signal Station at Mispec, planned a year earlier, were finally submitted in September, and in November, as traffic in the St. Lawrence system dwindled for the winter, activity increased in Saint John. By December, four or five ships a day were waiting off Manawagonish Island for berths in the harbour, which led to the establishment of a special anchorage for waiting ships.

The armed merchant cruiser H.M.S. Laconia under repair in the Saint John dry dock. Few new ships were built in Saint John during the Second World War due to the demand for this type of repair activity. Milner Collection

H.M.C.S. Zoarces, one of many ex-civilian vessels that did yeoman service throughout the Second World War as part of the Saint John fleet. DND Photo

Sackville (on the left), Amherst (nearly ready for sea), and Moncton (still on the stocks) in Saint John in 1941. They were the only corvettes built east of Quebec during the Second World War. Harold Wright

The winter of 1940-1941 was perhaps the busiest yet. The first Saint John-built corvette, H.M.C.S. Amherst, was launched on December 4 with the wife of Nova Scotia’s lieutenant-governor on hand to do the honours. A steady stream of armed merchant cruisers used the dry dock, as did the battleship H.M.S. Ramilles in late winter. Tiner’s Point station opened on January 20, 1941, with a staff of six and direct telephone links to the N.C.S. office. Work on the Port War Signal Station at Mispec began in December, and the station went into service on March 10 with a regular staff of four officers and five signalmen. Meanwhile, from December 1940 to May 1941, an average of seventy ocean-going ships per month called at the port; about half were routed to Halifax or Sydney for transatlantic convoys.

Summer 1941 was quieter than normal, and even the number of ships clearing from ports in the Gulf of St. Lawrence was down. The reason for this is unclear, but by spring 1941 the war had settled into something of a routine. The intense battles with packs of U-boats in the North Atlantic over the previous winter had subsided, and in late June Germany invaded the Soviet Union, shifting almost everyone’s focus eastward. Whatever the reason, the tides of war carried fewer merchant ships to Saint John and other New Brunswick ports in 1941.

The dockyard, however, was busier than ever, repairing damage caused by winter storms and enemy action. By August, there were seven vessels in dry dock and three more berthed alongside waiting their turn. The second of the corvettes, H.M.C.S. Sackville, was launched in May. In July, Amherst underwent sea trials, while a third corvette, Moncton, rose slowly on her slip, delayed by repair work on other vessels. Meanwhile, the local naval establishment complained about too few harbour craft and the lack of a patrol vessel in the area. Cartier returned to Halifax in the summer and was soon condemned and discarded. H.M.C.S. Husky, a former yacht, arrived in September to take up patrol work, but one small, poorly armed vessel was hardly sufficient.

N.C.S. Saint John also dealt with crew trouble on foreign vessels. In peacetime, legal jurisdiction over foreign nationals on foreign-flagged vessels was limited. During the war, it was imperative to keep ships moving efficiently, so it became necessary to implement legal means to allow Canadian authorities to board ships and remove and detain “troublemakers” and saboteurs. Until 1941, there was no real authority outside the Criminal Code to do so, but a new “Merchant Seamen’s Order” passed in April allowed naval authorities to detain troublemakers for up to nine months or hold them in manning pools pending reassignment. The new order was invoked for the first time in Saint John in September and worked well. In time, a manning pool and proper consular facilities for foreign merchant seamen who routinely visited Saint John were also established, allowing for a more efficient handling of crew problems. Until then, the seamen’s “pool” was usually the local jail.

In early 1942, the establishment of a Naval Boarding Service (N.B.S.) in Saint John also helped to tackle problems with crews, potential sabotage, and living and working conditions. The N.B.S. boarded vessels to check their equipment, ascertain their mechanical condition, and provide the crew personal comforts — magazines, woollen hats, mittens, soap, and so on. This general “police” work helped ensure the smooth flow of traffic through the ports under Saint John’s jurisdiction. By 1942, the N.B.S.’s station wagon was logging a thousand miles or more a month visiting them.

The third winter of the war brought profound changes to the war at sea and, therefore, to the New Brunswick coast. The Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, thrust the Americans into the war and precipitated a sudden declaration of war on the United States by Nazi Germany two days later. The entire North Atlantic now became a war zone. The appearance of U-boats in the western Atlantic at the end of January 1942 and the wave of sinkings that followed created a tremendous increase in work for the Saint John routing staff, while crew troubles increased as merchant seamen grew wary — and weary — of submarine attacks. Captain Oland’s appeals for more ships for examination service and harbour and sea patrol duties took on a new urgency. By February, he was asking for the establishment of a convoy system in the Bay of Fundy to protect traffic into and out of Saint John.

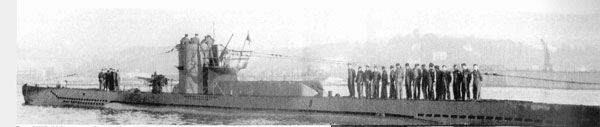

The immediate solution to the challenge of establishing convoys in the Bay of Fundy was to use the steady trickle of small, Halifax-based escorts passing through Saint John for repairs to run an ad hoc system. Three convoys sailed before the end of March 1942, an unknown number in April, and nine in May. Many escorts passed through the port in 1942, and the last of the Saint John-built corvettes, H.M.C.S. Moncton, conducted her sea trials in May. By spring, however, Saint John still lacked the warships needed to protect traffic properly. While Murray Stewart, Zoarces, Caribou, and Husky ran the examination service and Captor, Invader, and Vigil II secured the inner harbour, defence further to seaward relied on the army’s long-range guns at Mispec and on the regular traffic of small warships passing to and from Halifax. In May, so few escorts were available that the sailing of five vessels was delayed. In general, such delays were detrimental when every cargo and ship was urgently needed, but the delays in May 1942 probably saved several ships — and they certainly saved the Bay of Fundy from any intense enemy activity. That month, and for the only time in the war, two U-boats began to lurk off Saint John, instructed to probe the bay, report traffic, and attack targets of opportunity; one sub even had a spy to land.

The first to arrive was U-213, which left France on April 25 with orders to land a spy along the Fundy coast of New Brunswick and “where possible knock-off a steamer near Saint John before departure.” U-213 entered the bay on May 12 guided by inadequate charts and facing both fog and powerful tides, making her skipper anxious to complete his task and get out. The submarine passed along the New Brunswick shore, recording navigation light and markers, which were still functioning as in peacetime, and the sweeping of searchlights of Saint John’s defences. By the early morning of May 13, U-213 lay submerged near St. Martins, preparing to land Leutnant M.A. Langbein, also known in Canada as Alfred Haskins.

The German captain spent May 14 scouting the shoreline east of St. Martins through his periscope, trying to find a suitable landing site. Then, at 10:30 p.m., U-213 surfaced and approached to within twelve hundred yards of Melvin’s Beach, east of Salmon River. Shortly after midnight, an inflatable boat carrying Langbein, in full naval uniform so that if captured he would be considered a prisoner of war, rather than a spy — which would normally result in execution — and three crewmen pushed off through the gathering fog. What was supposed to be a short trip to the beach turned into a four-hour ordeal, as the Germans wrestled with the tide and struggled to find a suitable beach. Langbein was nonetheless landed a few miles east of St. Martins, and the inflatable boat returned to the submarine. On May 16, as the U-boat cleared the Bay of Fundy, the successful completion of the mission was radioed back to France. U-213’s mission was, in fact, only partially successful: although Langbein had been put ashore, U-213 had attacked no shipping in the bay. The only contact with the U-boat was made by a Norwegian destroyer off Yarmouth, which attacked on May 15 without result. No hint of her presence appears to have reached Saint John. Her captain blamed persistent poor weather for his inability to find a target, but Michael Hadley concludes that German U-boat headquarters blamed the captain’s “poor tactical record on lack of aggressiveness.”

Langbein fared little better as a spy. Once ashore he immediately buried his naval uniform and radio transmitter and, in civilian clothes, wandered into St. Martins as “Alfred Haskins.” He had been given outdated Canadian two-dollar bills and oversized American money as well. No one noticed, perhaps because, as Langbein later explained, he quickly learned to break the bills in places where few questions were asked. It also might account for his arrest in a Montreal brothel in early June for failing to pay his bill. “Booked [by the police] under a fictitious name, according to the conventions of the day for customers caught in flagrante,” Hadley writes, “he paid his caution and was quickly released.” This brush with the law does not appear to have alarmed Langbein. He had worked in Canada before the war and, as a patron of The Half Way speakeasy in Flin Flon, Manitoba — apparently often found in the arms of “Blonde Annie” and “Suede Anne” — he was familiar with Canada’s laws governing prostitution.

From June 1942 until November 1, 1944, Langbein lived in Ottawa. When his money finally ran out he surrendered to the R.C.M.P., but they refused to believe his story. Further investigation uncovered his radio and clothes from the beach east of St. Martins. Langbein spent the rest of the war in an internment camp and was repatriated in 1945.

The other submarine off Saint John in May 1942 posed a much greater threat, but its failure to encounter any shipping had long-term implications for the security of the port and the Bay of Fundy. In late May, U-553 penetrated the bay along the Nova Scotia coast, looking for less fog — which had hindered her reconnaissance of the province’s Atlantic shoreline — and specifically in search of targets using Saint John. The Germans knew that Saint John had a large harbour with deep water alongside and a dry dock. But that was about it.

U-553 had already made a name for herself. Earlier in the month, she had sunk the steamers Leto and Nicoya in the St. Lawrence River, the first vessels lost to enemy action in Canadian waters. The event dominated the Canadian news and raised a firestorm of debate in Parliament. It also prompted propaganda broadcasts worldwide from Germany lauding the success of “U-Thurmann,” which identified her captain as Korvettenleutnant Karl Thurmann. Unlike the captain of U-213, Thurmann was no shrinking violet.

After crossing the bay to Grand Manan, U-553 arrived off Saint John harbour in the early hours of May 27 and immediately surfaced in full moonlight to give Thurmann a look. His war diary records his reactions: “Six miles off St John. Radio and navigation beacons as in peacetime. Barrage [barrier] at harbour entrance with a powerful search light which apparently is tested a couple of times at the outset of darkness. Lay stopped on the surface.” Before diving, Thurmann signalled a report to headquarters, then spent the next four days watching the port. Canadian naval intelligence knew he was in the area but Thurmann’s brazen use of his wireless off Saint John every night went undetected. Direction-finding stations had difficulty early in the war locating and intercepting transmissions from close inshore. As a result, there is no evidence that Thurmann’s presence off Saint John occasioned extraordinary care in routing — or delayed the sailing of five ships that month from Saint John until escorts could be found. So U-553 had arrived during a fortuitous lull in activity, which had long-term implications. Thurmann was inclined to blame attacks on shipping elsewhere for a general chill in movements in the Bay of Fundy, and he found little to report during his stay in the bay.

Nor did the defences of Saint John ever detect U-553, although they had their chances. In the dark hours of the morning of May 29, U-553 lay on the surface and watched an exercise off the port. Aircraft flew low overhead and escorts steamed to within a thousand yards without ever seeing the U-boat. Thurmann put these efforts down as an exercise, and he was probably right, since there is no indication they were hunting for him. At this stage of the war, few Canadian small ships or aircraft had radar, and finding U-553 in the darkness would have been a stroke of luck.

More important, Thurmann reported to headquarters that Saint John “is not used as a loading terminal for convoys.” The “lively coming and going” of small escort vessels suggested to him that Saint John was a support base for escorts, used to “take the pressure off the convoy assembly ports.”

U-553 went on to sink several ships off Nova Scotia and in the Gulf of Maine before heading home. She was the last U-boat to enter the Bay of Fundy. Thurmann’s reports — totally wrong in his assessment of the importance of Saint John as a loading terminal — probably caused this abiding German disinterest. Certainly there were targets aplenty: over sixty ocean-going vessels per month between November 1941 and May 1942. It is clear that the Germans had no idea of the seasonal fluctuations in shipping using Saint John. Thurmann would have found ample targets in March 1942, when seventy-four ocean-going ships entered the port and most left unescorted. By May, the number was down to thirty-two, and outward shipping was travelling in convoy. The dense fog that shrouded the bay in June and delayed shipping that month did not help the German assessment.

Perhaps in response to the presence of U-boats in the bay, in August the first reinforcements for Saint John’s small naval forces arrived in the form of two Fairmile motor launches, Q022 and Q084. These 112-foot-long, diesel-powered vessels carried a 12-pounder gun and depth charges. They were limited to carrying out regular anti-submarine sweeps in the harbour approaches, but it was a start. In October, the Western Isles trawler H.M.C.S. Anticosti arrived to conduct anti-submarine patrols; she was joined by her sister ship, H.M.C.S. Magdalen, in November. These small escorts were part of a class of sixteen built in Canada to British contracts. Eight were retained by the R.C.N. and manned by Canadian crews for service in Canadian waters, including Anticosti and Magdalen. They represented a modest but important addition to the port’s defences and — for the most part — its “naval force” for the balance of the war. The opening of a new operations room for the harbour in November 1942 facilitated coordination of their efforts with the army’s coastal defences.

Two other significant developments in the latter half of 1942 also shaped Saint John’s naval operations. In September, a separate convoy series designated “FH” began operating between Saint John and Halifax. These were never big — seldom more than half a dozen vessels — but they sailed frequently: an average of seven convoys a month in 1942 and 1943. During the first thirteen months of their operation — until the end of the 1943 summer season — seventy-five percent of Saint John’s outbound shipping travelled in FH convoys. Organizing them was the role of the Naval Control of Shipping staff. Starting in September 1942, so, too, was control of all routing from ports in Prince Edward Island and Quebec’s Magdalen Islands. This completed the N.C.S. network based in Saint John.

As 1942 drew to a close, New Brunswick also became involved in tracking U-boats. During the summer campaign, the R.C.N. had found that it lacked sufficient stations for tracking U-boats by direction finding (D.F.) — whereby their radio transmissions were used to plot their location. Clearly this had been the case with U-553, which had surfaced each night it lay off Saint John to send a signal home. The direction of these signals ought to have been plotted at Canada’s six D.F. stations and U-553’s positions determined by tracing these to the intersection of the lines. Prior to the war, this had been done by the Department of Transportation as part of its marine communications system, and the department still operated the stations in use by 1942. But the navy needed more, especially on the east coast, to track U-boats.

So, in 1942, the R.C.N. started building seven D.F. stations of its own, including one at Coverdale (Riverview), New Brunswick. H.M.C. Naval Radio Station Coverdale opened in 1943 with twenty operator positions. It listened for selected frequencies, primarily U-boat radios, and passed bearings to Ottawa, where they were compiled with others and used as the basis for launching anti-submarine searches. The Coverdale station, like the others, was staffed almost entirely by members of the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (the WRENS), and commanded from 1943 until 1945 by Lieutenant Evelyn Cross. Their work was so good that even the US Navy intelligence branch sent frequent compliments. This “secret” installation survived the war and continued to do radio intelligence work until it closed in the early 1970s.

WREN Jaqui LaPointe operating an intercept receiver at H.M.C.S. Coverdale at Riverview, New Brunswick, August 1945. LAC PA-142540

By 1943, the Saint John naval establishment had grown well beyond its tiny origins at 250 Prince William Street. The February report listed extensive new buildings in service at Reed’s Point (near the intersection of modern-day Prince William and St. James streets), including workshops, D.E.M.S. offices, an asdic (sonar) building, sick bay, engineering stores, victualling depot, N.C.S. offices, naval stores, and a base superintendent’s office. The War Watch Station at Tiner’s Point and Port War Signal Station at Mispec tracked ships in and out, while the port’s little fleet operated from Lower Cove. That fleet now included fourteen vessels: Anticosti and Magdalen provided anti-submarine patrols; French, Zoarces, Murray Stewart, and Rayon d’Or ran the examination services; and Captor, Invader, and Vigil II, supported by Harbour Craft numbers 9, 15, 17, 19, and 148, secured the inner harbour. D.E.M.S. work continued on both freighters and large liners using the dockyard.

After a remarkably quiet period in late 1942, when shipping was drawn off by the Allied landings in North Africa, the port of Saint John became busy again in late winter 1943, and the volume continued to grow over the spring. In May, thirty-four ships were in the harbour, twenty-seven alongside handling cargo and six under repair. As the N.C.S. report observed, “A berth is seldom vacant for more than a few hours.” The spring freshet pouring out of the St. John River made ship handling in the harbour difficult and occasioned delays. Ships calling at the port now included Swedish vessels engaged in relief for German-occupied Greece: seven were loading in May and were routed for the Mediterranean. Four ships from neutral Ireland were also in Saint John that month. And although activity in the Gulf of St. Lawrence had not yet commenced, the N.C.S. staff made an estimated 150 trips in February carrying messages to ships. February also witnessed the departure of the first Saint John-built merchant ship, the Rockwood Park, which sailed in FH 39 for Halifax, while the Dartmouth Park began engine trials in the harbour in April. The only bad news was the loss of Harbour Craft 15 along with an officer and five ratings in April. Her wreckage came ashore on the Courtney Bay breakwater.

Home of H.M.C.S. Brunswicker at Lower Cove (white building in the foreground) in the 1950s and 1960s before being relocated to Barrack Green. H.M.C.S. Captor, the wartime naval establishment, was located on Prince William Street across from the Harbours Board Building. Harold Wright

The Allies won a major victory in the Battle of the Atlantic in May 1943, inflicting a decisive defeat on German U-boat wolf packs in mid-ocean. That victory caused no change to the routine at Saint John, but the spring weather brought the U-boats back to nearby waters for more clandestine activity. Early that month, U-262 arrived off North Point, P.E.I., in hopes of recovering escaped U-boat P.O.W.s from Canada. This was the first of two little-known P.O.W. capers in which New Brunswick played a central role.

The May escapade involved German sailors held at Camp 70, near Fredericton. They had used a simple but sophisticated code in personal letters home and received information cleverly hidden in packages, books, and letters to arrange a mass escape and recovery by submarine. In preparation, the P.O.W.s produced maps of their route to Moncton, Sackville, Cape Tormentine, Summerside, and Tidnish, plus disguises and the necessary Canadian identity documents. Although it was tracked closely by naval intelligence, U-262 arrived safely off North Point on May 1 and waited for most of a week at the designated rendezvous. Unfortunately for the P.O.W.s at Camp 70, their elaborate and long-planned escape from central New Brunswick was scuppered by a completely uncoordinated — and failed — escape attempt a few days earlier by a prisoner who was not part of the U-boat group. The resulting increase in camp security undid the mass escape attempt. U-262 got away safely.

Harbour Craft 15, one of the vessels that patrolled the approaches to Saint John harbour; she went down with all hands in 1944. DND Photo

Another attempt by U-boat P.O.W.s, in September 1943, went somewhat better. This time, a large group planned to escape via a tunnel from Camp Bowmanville in Ontario. The plan, code named Operation Kiebitz, called for the escape of seven U-boat captains and senior officers led by the famous U-boat ace Otto Kretschmer, captured in March 1941. Clever detective work by naval intelligence and the R.C.M.P. unearthed the detailed plans hidden in the covers of books mailed to the P.O.W.s. The information was photographed, and the rebound books were allowed to go forward as part of regular P.O.W. mail.

Rather than simply expose the escape plot, Canadian authorities planned to use it to trap the U-boat sent to rescue the escapees. Each escapee would be captured as he emerged from the tunnel and held in isolation. Then the Canadian media would be informed of a mass escape and, periodically, news of the capture of one or two P.O.W.s — progressively further east — would be released to maintain the fiction of the escape. German naval intelligence, of course, would be listening to Canadian radio and reading Canadian papers, so the ruse simply would confirm the success of the initial escape and the movement of the remaining escapees toward the rendezvous.

The P.O.W.s and U-536 were to meet at Maisonette Point, the northern arm of Caraquet Bay in northeastern New Brunswick. The R.C.N. planned to set up two portable radar sets on Miscou Island to help track the U-boat, and trained a special boarding party armed with pistols, hand grenades, daggers, smoke grenades, and a long chain that would be dropped down the open hatches of the sub so they could not be closed quickly, thereby preventing the sub from submerging. The boarding party would be borne in a specially acquired lobster boat that would race alongside once the sub was on the surface. When the British complained that this was all rather a bit naive, the R.C.N. simply resolved to sink the U-boat.

The mass escape plan collapsed, however, when camp guards — who had not been informed of the elaborate Canadian counterplan — found the tunnel. Undeterred, Kretschmer’s group threw its support behind Kapitänleutnant Wolfgang Heyda, who had his own plan to slip out along a power line in a bosun’s chair. But his captors discovered this scheme, too, and he was allowed to escape on September 24, 1943, and travel to northern New Brunswick by train as a “Mr. Fred Thomlinson,” a geologist working for the R.C.N. He even had a nicely forged authorization signed by Rear Admiral L.W. Murray, commanding officer, Atlantic Coast. Heyda arrived in Bathurst and switched trains to Grand-Anse, then walked the final leg to Maisonette Point. After passing through the army cordon securing the point and its lighthouse, Heyda camped on the beach. U-536 entered the Bay of Chaleur about the same time, and by September 28 was in place, waiting for the signal. Once contact was made, an inflatable boat was to be sent ashore to ferry him to the sub.

In the meantime, the R.C.N. had amassed a large force of nine anti-submarine ships — a destroyer, three corvettes, and five Bangor class escorts — to seal off the bay and trap the sub. Among these was H.M.C.S. Rimouski, a corvette with a radically new form of nighttime camouflage called “diffused lighting.” This system consisted of sensors that read the ambient light, a network of lights positioned around the ship to illuminate it, and a control network. The intent — and the effect — was to make the ship, which would normally appear as a black shape against a night horizon, invisible at night. It was Rimouski’s job to slip into the bay and assume the guise of a small coastal ship.

The final part of the scheme consisted of a small group of Canadian naval personnel, led by Lieutenant Commander Desmond W. Piers, R.C.N., camped out in the lighthouse. Among them was Lieutenant Commander Sorenson, R.C.N.V.R., from naval intelligence and, recently, professor of German language at the University of Saskatchewan. Unwisely, perhaps, they arrested Heyda as soon as he arrived and passed him off to the R.C.M.P., who hustled him back to Bowmanville.

As U-536 watched for lights from Maisonette Point, her captain grew increasingly uneasy about the warship patrolling the bay. If this was not bad enough, U-536 received curious communications on frequencies not previously arranged using an unknown code word. Even worse, Piers’s group at the lighthouse apparently sent light signals from the beach saying “komm, komm.” The complexity of the Canadian trap and the enthusiasm to sink U-536 finally undid the plot. Once the temporary radar stations got a fix on the submarine, she was attacked with depth charges. Spooked by the overzealous Canadians, U-536 headed for open water on the night of September 27 to the sounds of depth charges exploding in the distance.

Ironically, the only Canadian vessel to make contact with U-536 in the Bay of Chaleur was a fishing boat, which briefly caught the sub in her trawl. U-536’s hydrophone operator could hear the vessel’s winches working hard to pull in her remarkable catch. But U-536 was the big one that got away, trailing the net from her hull as proof of her escape — at least for the moment. U-536 never made it home; in an unrelated action, she was sunk by an R.C.N. hunting group in the eastern Atlantic.

After the P.O.W. escapades of 1943, naval activities in New Brunswick became routine for the balance of the war. Shipping out of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, the Gaspé, and the Magdalen Islands followed the usual seasonal pattern: busy in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in summer, quiet in Saint John; then, busy in the winter months in Saint John while the gulf was iced in. R.C.A.F. training squadrons at Chatham and Pennfield Ridge flew occasional patrols to seaward.

Saint John’s naval reserve division, now renamed H.M.C.S. Brunswicker, also had a busy war. The new naval establishment provided training help for the reserve division itself and for the recruits who passed through on their way to active service. By 1945, Brunswicker had enlisted and processed 2,292 officers and men who went on to serve in the R.C.N.V.R. When a large new naval recruit base, H.M.C.S. Cornwallis, opened across the Bay of Fundy at Deep Brook, Nova Scotia, Brunswicker took charge of men arriving in Saint John by rail en route to the base via the Saint John-to-Digby ferry. When the WRENs were established in 1942, Brunswicker also took a lead in recruiting for them. One benefit the reserve division enjoyed was the opportunity to provide training aboard a great variety of warships under repair or refit at the dockyard.

Perhaps the biggest development in 1943 was construction of the Naval Armaments Depot at Renous, near Blackville. This had long been in the plans, as the naval depot at Halifax needed an inland reserve site accessible by rail. The depot was opened in 1944 and operated until 1978, by which time plans were under way to redevelop the site as a maximum security penitentiary (which opened in 1987).

In 1944 and 1945, U-boats returned to Canadian waters for their second — and last — campaign of the war. None of these U-boats penetrated the Bay of Fundy or landed spies along New Brunswick’s shores; by comparison with events in 1942, this was a quiet campaign. The U-boats scored a number of signal successes, such as the sinking of the corvette Shawinigan in the Cabot Strait and two minesweepers in the approaches to Halifax harbour, but they did little to disrupt the movement of traffic. The major characteristic of this inshore campaign late in the war was the U-boats’ reliance on their new schnorkel devices, which allowed them to operate fully submerged all the time. As a result, searching warships found these U-boats almost impossible to locate as they used the complex mixture of inshore waters, tides, and rocky bottoms to evade detection.

The emerging science of oceanography played an important role in learning how to locate these elusive submarines, and New Brunswick was involved from the outset. In 1944, the only oceanographic research operation on the east coast was located at the Atlantic Biological Station (A.B.S.) at St. Andrews, New Brunswick. Established in 1899 as Canada’s first marine research station, it had moved into permanent quarters on the St. Croix River in 1908. In 1928, the station received a new hydrographer, Dr. Henry B. Hachey, a former professor of physics at the University of New Brunswick. Born in Bathurst in 1901, Hachey held a reserve captaincy in the North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment and left the A.B.S. in 1940 to join the regiment upon its mobilization. After service overseas as the regimental adjutant and a company commander, Hachey returned to Canada in 1943 to work for the army on chemical warfare and operational research. It was Major Hachey, the oceanographer and physicist, who was seconded to the Royal Canadian Navy in 1944 to begin work on the mysteries of inshore anti-submarine warfare.

Hachey established himself in familiar surroundings in St. Andrews and began processing the data from bottom and bathythermograph (the measurement of temperature in relation to depth) surveys already conducted off Nova Scotia and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence by the R.C.N. It was Hachey who, in fall 1944, produced the first scientific studies on sonar sound propagation for Canadian waters; these formed the basis of R.C.N. anti-submarine warfare off Canada in the last winter of the War.

Hachey continued this work until 1946, when he was formally discharged from the army with the rank of lieutenant-colonel and awarded an M.B.E. by King George VI for his service. That year, Hachey became the chief oceanographer of Canada and continued to play a crucial role in the ongoing struggle to master sound propagation for anti-submarine purposes until his retirement in 1964. During that period, the R.C.N. became a world leader in anti-submarine warfare, a success that in no small way began in New Brunswick with a New Brunswick scientist.

1 R.C.A.F. aircraft, operating out of Millidgeville airport, carried out fire control for Saint John’s coastal defence batteries.