INTRODUCTION

The importance of Rome’s geographical position, situated where river and land routes meet and where Etruria is linked with Latium and Campania by the ford below Tiber Island, is not difficult to understand. To experience the interplay of this geography at first hand, one need only follow Via della Lungaretta, which traces the course of the ancient Via Aurelia originating in southern Etruria, from the slopes of the Janiculum to the Tiber. There the modern Ponte Palatino crosses the river at a short distance from the ancient Pons Sublicius. Leaving the bridge, the traveler enters the Forum Boarium, the ancestral market, which was older than the city itself. Beyond the valley of the Circus Maximus lies the point where Via Appia and Via Latina split off and begin their descent southward toward Campania. This traffic route, preserved in the modern city, accounts clearly enough for the rise of an important settlement in this location.

The Greek writer Strabo, who lived during the Augustan Age, noted the absence of settlements of any importance between Rome and its port, Ostia, at the mouth of the Tiber. But this was not always the case. Between the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age, villages dotted almost every hill along the river. At the site where Rome would one day rise, a settlement occupied the Capitoline from as early as the fourteenth century BC. Tradition holds that the city was formed from the incorporation of surrounding villages into the most important settlement in the region, that on the Palatine. This process coincided with the increase in agricultural productivity and with the beginning of Greek colonization, which—not by chance—corresponds to the traditional date of Rome’s founding: the middle of the eighth century BC. Almost immediately Rome developed contacts with these first colonies, especially Ischia and Cumae, as eighth-century Greek pottery found in the Forum Boarium attests.

An important phase in the early development of the city occurred in the second half of the seventh century BC. According to tradition, Ancus Marcius built the first wooden bridge over the Tiber, the Pons Sublicius, and protected its bridgehead on the right bank by occupying the Janiculum. At the same time, he founded Ostia and secured its connection with Rome by razing all settlements between the port and the city on the river’s left bank. Archaeological evidence appears to confirm this tradition.

At the end of the seventh century, the potential inherent in the new urban center and its favorable setting attracted the Etruscans, for whom Rome had become a key location. During the century in which it was ruled by an Etruscan dynasty, Rome achieved its definitive urban form without losing its ethnic character and Latin culture. The city was divided into four administrative regions or territorial tribes (Palatina, Collina, Esquilina, and Suburana) and constituted an area considerably larger than the original extent of the Palatine, as can be observed in the circuit of the Servian Walls, whose fourth-century BC reconstruction follows almost perfectly the earlier sixth-century course (FIG. 1). The area of the city, though not fully inhabited, was no less than 426 hectares; larger, that is, than any other city on the Italian peninsula. The wealth and power of the “Grand Rome of the Tarquins” are also reflected in the number and size of the sanctuaries constructed at that time. The sanctuary of Capitoline Jupiter is by far the largest known Etruscan temple.

Yet the building activity of the Etruscan rulers was not limited to religious sanctuaries. In addition to the vast circuit of walls, built of cappellaccio blocks in its earliest phase (the middle of the sixth century BC), the Tarquins also installed an impressive system of channels and drainage sewers. Once the unhealthy swamps in the low-lying areas of the valley were cleared, further urban development became possible. The two principal conduits in the system are the Cloaca Maxima and the channel that drained the Vallis Murcia. The former reclaimed the Forum valley, which was first paved at that time, and the latter cleared the way for construction of the Circus Maximus; on that site the Tarquins were supposed to have erected the first formal structure for the games.

The text of the first treaty between Rome and Carthage, passed down to us by Polybius and dated to the early years of the Republic, conveys a sense of the city’s territorial expansion during the sixth century. The document reveals that the territory dominated by Rome at that time extended as far as Circeo and Terracina.

In the decades after 509 BC, the year in which the Tarquins were expelled, building activity continued at a remarkable pace. During these years, some of the most important sanctuaries were built, including the temples of Saturn and of the Castors in the Forum, and those of Ceres and Mercury at the foot of the Aventine. The impact of Greek culture, evident in these foundations, is also reflected in the importation of Greek ceramics, which continued, without significant change, until the middle of the fifth century. When the Decemviri assumed control of the government and the Laws of the Twelve Tables were promulgated, a serious crisis emerged, whose effects were felt in the rest of Italy, including Etruria and Magna Graecia. This crisis coincided with the most turbulent phase in the struggle between the patrician and plebeian classes and with the loss of the territories of southern Latium following the invasion of the Volscians. This same period witnessed the foundation of the important Temple of Apollo in the Campus Martius. Among other public buildings erected at this time was the Villa Publica, which housed the newly established office of the censor.

At the beginning of the fourth century, the city recovered from the losses of the preceding century, a time characterized by life-or-death struggles, lost in obscurity, with surrounding peoples. The first sign of this recovery was the destruction of the city’s most dangerous rival, the Etruscan city of Veii, after a ten-year siege; the attack and conquest by the Gauls ensued immediately afterward. The Roman annalistic tradition has probably exaggerated the importance of this event by attributing the destruction of a large portion of the city’s oldest documents to the fire set by the Gauls; this loss is said to account for the lack of detailed knowledge about Rome’s first centuries. Archaeological evidence, however, does not confirm tradition in this case. Other factors, such as the paucity of written documentation at such an early period, would appear to explain the lack of information for the years prior to 390 BC. The irregularity evident in the most ancient regions of the city, which Livy attributes to hasty reconstruction after the Gallic sack, might be explained more plausibly as the result of long and progressive growth, similar to that observed in Athens. A total reconstruction of the city in the fourth century would certainly have resulted in a more methodical organization. Moreover, the buildings whose archaic and fourth-century phases have survived (such as the Regia and a number of temples) show no noteworthy signs of sudden reconstruction or even of changes in plan or orientation.

Evident resumption in building activity occurs in the fourth and third centuries BC. The most impressive undertaking is the complete reconstruction of the walls, which had proved inadequate to withstand the Gallic assault. Construction of this massive defense system built of Grotta Oscura tufa began in 378 BC and was completed around the middle of the century. At the same time, large building projects were undertaken on the Capitoline and Palatine Hills, and numerous temples were built or rebuilt (e.g., Temples A and C in Largo Argentina). The level of urban planning undertaken at that time can be seen in the construction of several roads, Via Appia in particular, and above all in the erection of the first aqueduct, begun in 312 BC by the censor Appius Claudius Caecus. Artists from Magna Graecia had already been working in Rome by the beginning of the fifth century, but now such activity increased, a sign that the median level of culture had risen and that the Romans valued the products of Greek art. Workshops producing ceramics of high quality begin to appear in the city; their products were exported throughout the western Mediterranean. Bronze statues start showing up in public buildings and spaces: in the second half of the fourth century BC, statues of Pythagoras and Alcibiades, certainly the work of artists from Magna Graecia, are recorded as standing in the Comitium. In 296, the ancient terracotta quadriga that had adorned the peak of the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, the work of the Etruscan artist Vulca, was replaced by one in bronze. During the same years, two colossal statues, one of Hercules, the other of Jupiter, were erected in the Area Capitolina; statues of the Roman kings may also have stood nearby. The famous bronze known as the Capitoline Brutus gives an idea of the quality of these works. Increasingly, Greek writers begin to focus on Rome; one author goes so far as to call it a “Greek city.” This impressive development coincides with the conquest of Italy—from the Samnite Wars to the war against Tarentum and Pyrrhus—and subsequently of Sicily and Sardinia after the First Punic War.

This era represents the classical phase of the Roman Republic, whose expansion was based primarily on a substantial class of small- and middle-sized landowners that formed the core of the army. Late Republican and Imperial writers would come to idealize this period, creating the fiction that Rome was in those years poor, rustic, and largely unsympathetic to Greek culture. This idea, which endures to this day, is certainly misguided, if not completely erroneous.

Until the Second Punic War, Roman territory was limited to the dimensions of a city-state; it was the center of a confederation. But from the beginning of the second century BC, a crisis emerged that progressively undermined the basic structure of the Republic and resulted in the creation of the empire. Leaving aside Rome’s economic and social development, the last two centuries of the Republic were decisive in shaping the city’s subsequent growth. On the one hand, the huge increase in Rome’s population, resulting from migration that gradually emptied cities throughout Italy, gave rise to large working-class neighborhoods, with rental flats in multistory buildings—the insulae that housed many of Rome’s inhabitants during the Imperial period as well. On the other hand, the desire to win political support from this mass of citizens led Rome’s ruling families to display their power and prestige as a political strategy. In time, the Forum, the Capitoline, and the Campus Martius were strewn with porticoes, gardens, monumental temples, and entertainment complexes. New facilities, including a port, warehouses, and aqueducts, arose to channel supplies into the city. The dual phenomenon of function and propaganda, resulting in the subdivision of the city into areas with specialized activities, together with the emergence of large residential and commercial quarters, came to characterize the city as early as the Imperial period.

The phenomenon of urban development based on the display of wealth and power is a distinguishing characteristic of the Forum, the Capitoline, and the Campus Martius. The latter in particular gradually assumed a monumental appearance: in the second century BC, a number of temples and porticoes, benefiting from the input of Greek architects and artists, arose in the vicinity of the Circus Flaminius; the building activities of Pompey, Caesar, and Augustus accentuated this development, facilitated by the public character of the region. Strabo provides a lively description of the area at the beginning of the Imperial period: alongside spaces left in their natural state lay an uninterrupted series of public buildings, porticoes, temples, baths, three theaters, and an amphitheater, all constructed by the Republican nobles, whose internecine wars would eventually oust them from power. The greatest developer was the most capable member of this nobility, Augustus, the heir and successor of Divus Julius.

This monumental character informed other areas of the city as well, such as the Forum Holitorium and the Forum Boarium, whose mercantile functions extended to the large commercial district that arose south of the Aventine at the beginning of the second century BC. Monte Testaccio, the “mountain of potsherds,” attests to the level of commerce undertaken here.

Along with the evident growth of public projects, we find a parallel expansion in the construction of private dwellings of two types: insulae, the large, multistory tenement houses that appear now for the first time but which, though often rebuilt during the Imperial period, disappeared leaving few traces, and domūs, the homes of the wealthy, which resemble the more luxurious Hellenistic residences. The domus is characterized by the addition of a Greek colonnaded courtyard (peristyle) to the traditional Roman atrium plan and the use of ever more elaborate decorations, such as marble and mosaic pavements, wall paintings, and gilded ceilings. Numerous remains of houses of this sort have been found within the city, especially on the Palatine and Esquiline.

We learn from Cicero that Caesar was planning a complete reconfiguration of the city, involving a large-scale overhaul of various regions, especially the Campus Martius and Trastevere. Among other projects, he planned to alter the course of the Tiber, a move that would have eliminated the large bend that formed the Campus Martius and united it with the Ager Vaticanus. The death of the dictator put an end to these works, but Caesar’s activities elsewhere shaped the character of the city’s center: the destruction of the Comitium and the construction of the Curia Iulia, the Basilica Iulia, and the new Rostra defined the new orientation of the ancient Republican forum, while the construction of the Forum of Caesar opened the way for the future Imperial fora.

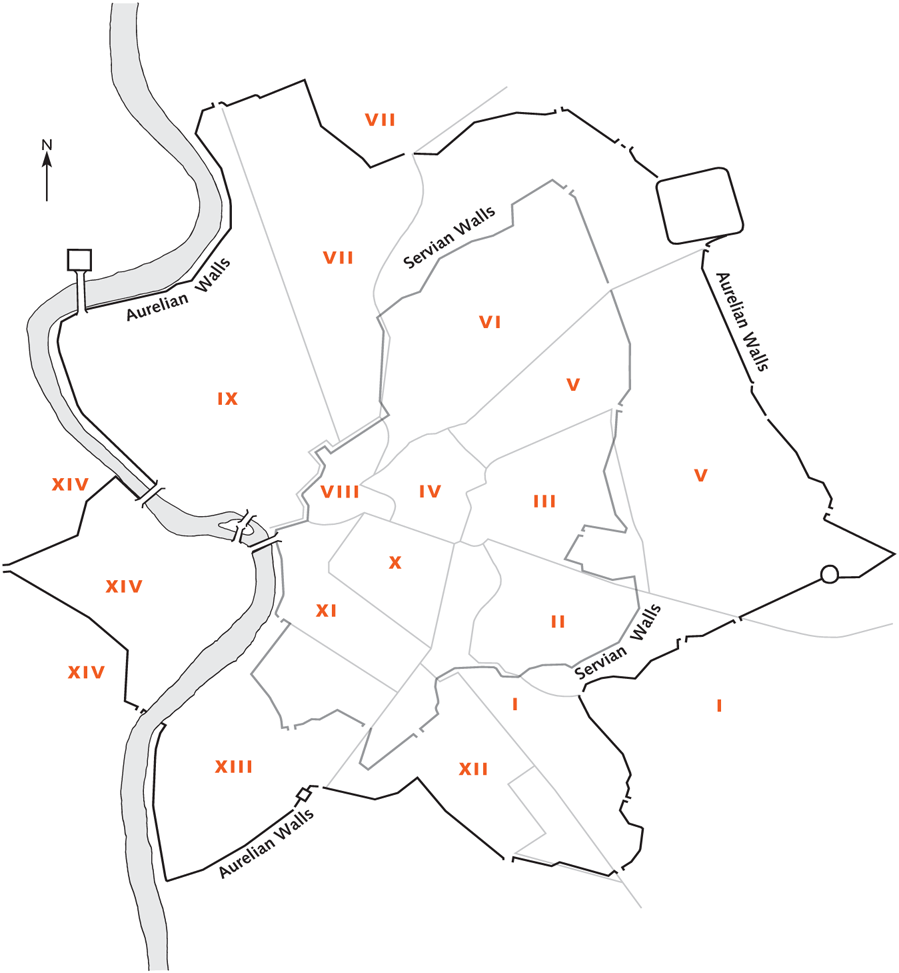

Augustus’s urban program was less grandiose and radical than Caesar’s, although this did not prevent him from associating himself directly with his great-uncle’s work. The city was totally restructured and divided into fourteen regions, in a plan that remained intact until late antiquity (FIG. 2). Along with this new organization, Augustus instituted a corps of vigiles, who served as nighttime police and firemen; he defined the limits of the Tiber’s banks and bed; and he built new aqueducts, the first public bath complex (that of Agrippa), two theaters, an amphitheater, and libraries open to the public. No fewer than 82 sanctuaries were reconstructed or restored during his reign. The Roman Forum, which was losing the political function that it possessed from the city’s founding, acquired its definitive character by becoming a monumental plaza. Augustus also situated a new forum, the Forum Augustum, alongside the earlier Forum of Caesar. Above all, the Campus Martius became the focus for most of the activity undertaken by Augustus and members of his court. It was at the edge of the Campus Martius that Augustus erected his dynastic tomb, the resting place for the emperor, his family, and his successors.

The subsequent emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty stayed more or less within the lines set by Augustus; only Nero broke out of the mold in the aftermath of the great fire of AD 64, which leveled three of the Augustan regions and severely damaged seven, leaving only four intact. In the years that followed, Nero began construction of the Domus Aurea, transforming much of the city center into a kind of gigantic villa, a tangible sign of the emperor’s autocratic aims. On the other hand, the crisis resulted in the elaboration of an urban policy that, according to Tacitus, required the renovated areas of the city to be regularized, endowed with larger streets, and flanked by porticoes. Structures employing common walls were forbidden; limits were set on building heights; and the use of flammable material was restricted (the new building code called almost exclusively for stone and brick construction). The market on the Caelian Hill known as the Macellum Magnum and the Neronian Baths in the Campus Martius, probably the first example of a bath complex with the symmetrical plan that thereafter became canonical, are among the important public buildings erected in the Neronian period.

Disasters also struck the city during the Flavian period, such as the fire on the Capitoline in AD 69 and another in the Campus Martius and on the Capitoline in AD 80, a little more than ten years later. The first two Flavian emperors rebuilt the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus and repaired other buildings damaged by fire. But they are best known for dismantling the Domus Aurea, whose vast spaces, with the exception of a small section reserved perhaps for the Domus Titi, were restored to public use: the villa’s pool was drained and in its place an enormous amphitheater, the Colosseum, arose. The Flavians reconstructed the temple of Divus Claudius, which Nero had turned into a nymphaeum. The Baths of Titus went up quickly alongside the Domus Aurea; these were probably nothing more than a modification of Nero’s private baths. The statues that Nero had collected, mostly in Greece and Asia Minor, to adorn his residence were set up in a new monumental piazza, the Temple of Peace. If their principate is seen as anti-Neronian, at least in its public building program, in their overall policy of urban development the Flavians found it necessary to follow the earlier plans. Completion of Nero’s nova urbs was, after all, not feasible in the short period of four years between the fire and the emperor’s death. We know that in AD 73 Vespasian and Titus resumed an almost forgotten Republican magistracy, the censorship. They took this extraordinary step to enlarge Rome’s sacred boundary—the pomerium—an action that was probably essential to a general reconfiguration of the city.

FIGURE 2. The fourteen Augustan regions: I Porta Capena. II Caelimontium. III Isis et Serapis. IV Templum Pacis. V Esquiliae. VI Alta Semita. VII Via Lata. VIII Forum Romanum. IX Circus Flaminius. X Palatium. XI Circus Maximus. XII Piscina Publica. XIII Aventinus. XIV Transtiberim.

Domitian, the third emperor of the dynasty, vigorously carried on the work begun by his predecessors. The Campus Martius and Capitoline were almost completely rebuilt after the fire of AD 80. Other new buildings also went up at this time: a new forum, the Forum Transitorium (which would later be inaugurated by Nerva, from whom it derived its alternate name, the Forum of Nerva), the Arch of Titus, and the temple dedicated to Vespasian and Titus. In the Campus Martius, Domitian built the Stadium and the nearby Odeon, as well as the Templum Divorum, another building for the cult and burial of the Imperial family, like the temple of the Gens Flavia erected on the Quirinal at the spot where the Flavians had their private home. The new palace, built on the Palatine, was perhaps Domitian’s most spectacular building; it remained the official residence of the emperors until the very end of the empire.

The second century AD, from Trajan to the Severans, witnessed Rome’s greatest period of expansion, both geographic and demographic. The beginning of the century was signaled by the construction of the largest and most monumental of the Imperial fora, Trajan’s Forum. The area was already so overbuilt that it was necessary to cut away the saddle between the Quirinal and Capitoline and tear down various venerable buildings, probably including the old Atrium Libertatis. Still more profound changes took place in utilitarian building projects, both public and private. Apollodorus of Damascus, the same architect who designed Trajan’s Forum, was also responsible for Trajan’s Markets, which were closely integrated with the Forum, and for the large baths on the Oppian Hill where we first encounter the fully articulated classical form of the Imperial bath complex—the model for the Baths of Caracalla and Baths of Diocletian.

Building activity reached a high point with Hadrian and Antoninus Pius. The practice of giving the consular date on bricks begins in 123, a clear indication of the complete retooling of the furnaces for brick manufacture in response to this intense undertaking. The spike in building activity, while evident in individual monuments such as the Pantheon and the Temple of Venus and Rome or in the restorations of the palaces on the Palatine and of the Horti Sallustiani, is even more dramatic in the construction of entire neighborhoods with multistory insulae, such as the one in Region VII east of Via Lata, which was fully developed at that time. Nor should we forget the creation of Hadrian’s suburban palace, the Villa Adriana, and his mausoleum, destined for a new dynasty—that of the Antonines.

A large number of works were undertaken by the Severan emperors after the devastating fire of AD 191, including the reconstruction of the Temple of Peace, the Horrea Piperataria, and the Porticus of Octavia. A wing was added to the Imperial palace on the Palatine, which was endowed with a monumental facade, the Septizodium, facing Via Appia. But among the most impressive buildings of the period are the baths constructed in Region XII by Caracalla, the best-preserved bathing complex of Imperial Rome. To the same period belongs what is perhaps Rome’s largest sanctuary, the Temple of Serapis on the Quirinal.

Fragments of a marble plan, executed during the reign of Septimius Severus, provide a planimetric representation of the city in the years when it had reached its apogee. The plan covered a wall in the restored Temple of Peace. Building activity slowed down noticeably and almost stopped in the third century AD, as the empire encountered a violent economic and social crisis. The cessation of the use of brick stamps after Caracalla’s death—the practice was resumed only under Diocletian—is a symptom of the chaos of the times. Among the more important buildings of the third century are the Temple of Elagabalus on the Palatine and the Temple of the Sun erected by Aurelian in the Campus Martius. But the most notable construction of the period—striking testimony to the uneasy character of the age and clear evidence of the empire’s military weakness—are the fortification walls that Aurelian had erected around the city.

Building activity resumed in Rome under Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, much as it did elsewhere in an extensive and partly successful attempt to restructure the empire. The Fire of Carinus in AD 283 had destroyed a large part of central Rome; Caesar’s Forum, the Curia, the Temple of Saturn, and the porticoes of Pompey were hastily reconstructed, but the emperor wanted to associate his name with a large and entirely new building. To this end Diocletian built his eponymous baths, the largest ever constructed, at the juncture of the Viminal and Quirinal. It is possible that the Regionary Catalogues were compiled during these years. Although the precise function of these lists of buildings, set out region by region, is uncertain, they nonetheless provide precious information about the city at the end of the ancient period.

Even as late as Maxentius, who had chosen Rome for his capital and had clearly intended to refurbish the ancient and now impoverished city, we encounter a notable increase in the number of building projects. These include the reconstruction of the Temple of Venus and Rome, the building of a new Imperial villa with its own circus and dynastic mausoleum on Via Appia, and above all the erection of the great basilica, later named for Constantine, who completed some of Maxentius’s works and initiated others, such as the Baths of Constantine on the Quirinal, though these too may well have been begun by Maxentius. But Constantine’s attention soon turned to his new capital, Constantinopolis. From this point forward, Roman authorities focused their energies on simply preserving and restoring the old monuments, which, after falling into general disuse, were abandoned and destroyed over the years. In the meantime, a new city emerged alongside and extending beyond the old city: Christian Rome.

FIGURE 3. The City Walls. Plan of the Servian and Aurelian Walls.