CAELIAN

HISTORICAL NOTES

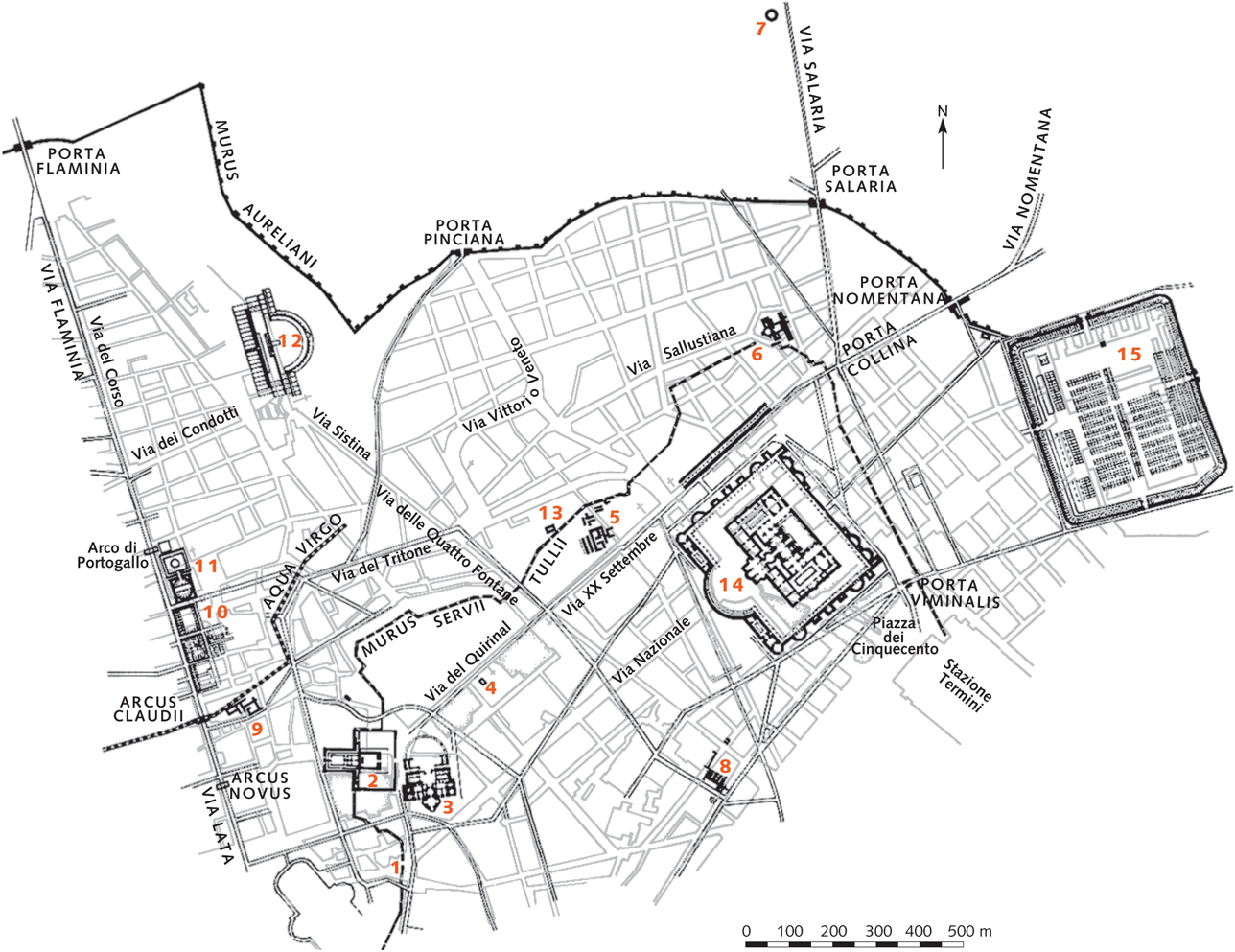

The Caelian Hill was divided among three Augustan regions: most of the area lies within the second region (Caelimontium); the southeastern slope up to Via Appia was part of the first (Porta Capena), while the eastern end, between the Lateran and Sessorium, belonged in part to the fifth (Exquiliae). Our knowledge of the boundaries between Regions I and II, however, is not completely secure (FIG. 2). It is likely that the first included the area near S. Gregorio, where the discovery of an inscription allows us to locate the Vicus Trium Ararum (Street of the Three Altars), which the Regionary Catalogues assign to Region I. Shaped like a long and narrow band, this region extended along the left (northeastern) side of Via Appia, including the ancient Temple of Mars and the valley of the Almo, and thus went well beyond the Aurelian Wall. It is important to keep in mind that Augustus’s division of the city into regions began from this area. The choice was possibly predicated on the fact that the ancient orientation of the city was based on the augurs’ line of observation. Standing on the Arx, they probably directed their gaze toward Mons Albanus, situated southeast of the city. This is in fact the orientation adopted by the Severan Marble Plan. Consequently, Region I took its name from Porta Capena, the ancient gate that opened onto Via Latina, the road that ran to Mons Albanus.

Colonnades must have lined the first stretch of the road (via tecta), while numerous tombs belonging especially to families of the Roman aristocracy stood alongside the thoroughfare, alternating with important cult places. Among these were the Temple of Honos et Virtus (immediately beyond Porta Capena), then that of the Tempestates (which must have been near the Tomb of the Scipiones), and finally the Temple of Mars (just outside Porta S. Sebastiano), all of which were on the left side of the street. The procession of knights known as the transvectio equitum began at this last temple and concluded in the Forum in front of the Temple of the Castors.

The sanctuary, fountain, and grove of the Camenae were situated in the little valley to the left of Porta Capena, at the foot of the Caelian, where King Numa was supposed to have met with the nymph Egeria. During the Empire, as Juvenal (3.10 ff.) indignantly records, the natural basin into which the fountain flowed was reconstructed in marble and frequented by Jewish merchants.

Roman proconsuls were greeted as they departed for their provinces just outside Porta Capena. The importance of Via Appia at this juncture necessitated the installation of a whole series of structures associated with the departure and return of magistrates during the Republic and of the emperors later on. The Senaculum, placed immediately outside the gate, similar to the one near the Temple of Bellona (see Campus Martius), must have served this function. This is where the Senate gathered, outside the urban pomerium, to meet with generals and magistrates returning from their provinces. The Mutatorium Caesaris, situated by the Regionary Catalogues in Region I, is located by a fragment of the Severan Marble Plan in this vicinity, immediately north of Via Appia. The building, which is represented as a large square hall supported by numerous columns, was probably used by the emperor for changing his clothes when departing from and returning to the city; that is, changing from the civilian toga to the military paludamentum or vice versa. It is certainly not by chance that Augustus had an altar built in this very area to Fortuna Redux—the divinity who ensured safe returns—in 19 BC on the occasion of his return from the east. Also associated with returns, as the name suggests, was the sanctuary of the god Rediculus, which also stood outside of Porta Capena and whose name was linked in legend with Hannibal, who, having advanced as far as this point, suddenly withdrew, terrified by unexpected visions.

The location of the Thermae Commodianae, situated by various sources in Region I, is not certain. We know that Commodus erected the complex between AD 183 and 187. The remains underneath the Church of S. Cesareo at the beginning of Via Appia, with floors in black-and-white mosaics depicting maritime scenes, have been ascribed to this complex.

The Caelian Hill, for the most part included within Augustan Region II, has the form of an elongated tongue (roughly 2 kilometers long and 500 meters wide at its maximum) and begins, like the Esquiline, in the area designated as ad Spem Veterem and extends all the way to the Colosseum.

The hill’s oldest name, Mons Querquetulanus (Oak Mountain), was, as ancient tradition confirms, replaced by the current name after the occupation by Caelius Vibenna, one of the two brothers from Vulci who were associates of Mastarna, the future Servius Tullius. Later on, the Caelian was also the site of the sanctuary of Minerva Capta (captive Minerva), a cult that was said, perhaps mistakenly, to have come from Falerii; this would have occurred in 241 BC, following the conquest and destruction of that city. We know that the temple stood on a secondary peak of the Caelian, called Caeliolus, which is probably to be identified as the place where the Church of SS. Quattro Coronati now stands; that is, outside Porta Querquetulana and the Servian Wall. A very ancient shrine to Diana, which L. Piso Caesoninus, a contemporary of Cicero, demolished, was built in this same area, as was (probably) a Temple of Hercules Victor, erected by Lucius Mummius between 146 and 142 BC; the dedicatory inscription is preserved in the Vatican Museums.

Several tombs in the area can be assigned to the Republic, including a chamber tomb that was recently excavated on the ancient Via Caelimontana, not far from S. Giovanni in Laterano, and which produced a large sarcophagus, funeral urns, and a store of terracottas and ceramics datable to around 300 BC. More recent Republican tombs were discovered a little farther on along the same street.

From the late Republican period, the district became somewhat more residential, although it continued to maintain its working-class character. At that time, several particularly luxurious homes appeared, such as that of Mamurra, Caesar’s praefectus fabrum, known best for the vicious attacks aimed at him by Catullus. His house was reportedly the first to have walls clad with marble slabs, and all of its columns were made of marble, cipollino and Carrara.

Violent fires struck the hill twice during the Imperial period: in AD 27 under Tiberius and again, famously, in 64 under Nero. The Claudium, the temple of the deified Claudius, dates to this period. Nero confiscated a series of affluent private houses from various persons whom he had condemned to death for having participated in the Pisonian conspiracy. Among the properties taken was that of the Laterani, which in subsequent years had a special place in the history of the city.

Nero incorporated the eastern retaining wall of the precinct of Claudius’s temple in an imposing nymphaeum, which probably served as a monumental backdrop for the Domus Aurea, built in the valley between the Caelian, Esquiline, and Palatine hills after the fire of 64. Another construction in the region, this time public and also initiated by Nero, is the Macellum Magnum, a large grocery market intended to replace the one that had stood near the Forum during the Republic; the building, completed in AD 59, was located in Region II. At one time, this complex was believed to have been located under the Church of Santo Stefano Rotondo, but this area, as recent excavations have confirmed, was the site of the Castra Peregrina. A fragment of the Severan Marble Plan that almost certainly depicts the Macellum Magnum can be located, for technical reasons, only in the area east of the Temple of Claudius; the market was thus between Via Celimontana and Via Claudia. The fragment, on which the name Macellum is inscribed, shows a nearly square structure, around 90 × 90 meters, surrounded on its exterior by shops opening onto a colonnaded porticus. Other shops faced the interior courtyard, in which there were triangular elements at the corners, probably fountains, and, in the center, a circular structure with columns, the tholos that was an integral feature of this type of building. Several Neronian coins, dated between 64 and 66, help reconstruct the appearance of this building.

One characteristic of the quarter was the presence of numerous barracks. In addition to the Fifth Cohort of the Vigiles (firemen) near S. Maria in Domnica (FIG. 56:3), there were the two barracks of the equites singulares, the emperor’s mounted guard. The first, in all likelihood built by Trajan, who created the corps, was situated in the area around Via Tasso, where there was also a Mithraeum; the second, the Castra Nova Equitum Singularium, was built by Septimius Severus where the houses of the Laterani had stood (FIG. 56:7). The remains of this building, underneath S. Giovanni in Laterano, have been seen at various times in recent centuries and were uncovered again in 1934/1938. Both barracks were closed by Constantine, who disbanded the equites singulares. The Lateran Basilica was then built over the second of these installations. The Castra Peregrina was another camp in which detachments of soldiers from provincial armies were employed in Rome for specific functions, such as police duty, courier service, or the provisioning of the court. Remains of this complex were discovered in 1905, south of Santo Stefano Rotondo (FIG. 56:4). The splendid Mithraeum beneath the church, recently explored, was associated with these barracks.

The slope of the hill facing the Esquiline and Colosseum must have been occupied by rental apartment buildings of several stories (insulae); during the Imperial period its summit was mostly occupied by the luxurious residences of the aristocracy. The villa of Domitia Lucilla Minor, the mother of Marcus Aurelius, was located here; in fact, the emperor was born in this house, and his bronze equestrian statue, now on the Capitoline, comes from the Caelian, after having long stood near S. Giovanni in Laterano. Commodus, the son of Marcus Aurelius, often resided on the Caelian and was ultimately killed there.

The houses of some of the most important aristocratic families of the fourth century AD stood along Via Celimontana, including those of the Valerii (near Santo Stefano Rotondo) and the Symmachi (near the military hospital).Remains of these residences have been found on various occasions. Many homes were not rebuilt after the sack of Alaric in 410. One street, certainly very ancient, ran along the entire ridge of the hill, as was the case on the Quirinal. Its ancient name is unknown (it may have been Via Caelimontana). This street passed through Porta Caelimontana, the Arch of Dolabella and Silanus, and extended as far as Porta Maggiore, following the modern Via di Santo Stefano Rotondo, Piazza S. Giovanni in Laterano, and Via Domenico Fontana. The four aqueducts that traversed the Caelian—the Appia, Marcia, Iulia, and Claudia—followed the same axis; the first three ran underground (the remains of pipes and conduits have been found at various points). The arches of the Aqua Claudia are still in large part visible and constitute an extension constructed by Nero to bring water to the Domus Aurea and the nymphaeum of the Temple of Claudius. Later on, Domitian extended the Aqua Claudia even farther, bringing it all the way to the Imperial residence on the Palatine. The arches were restored several times, in particular by Septimius Severus. From Porta Maggiore, where the initial stretch of the extension is well preserved, long sections of the aqueduct can be seen inside the Villa Wolkonsky, in Via Domenico Fontana, and on Piazza S. Giovanni; it can also be seen along Via di Santo Stefano Rotondo, near the military hospital, in the middle of Piazza della Navicella, adjacent to and above the Arch of Dolabella and Silanus, in the garden of the Passionists, and all the way to the Temple of Divine Claudius (SS. Giovanni e Paolo), where the large reservoir is located. This last section is also represented in a surviving fragment of the Severan Marble Plan.

Four streets branch off Via Caelimontana at the point where this major road enters the city through the gate of the same name: one of these passed within the Servian Wall and ran to the valley between the Palatine and Caelian (Clivus Scauri); another descended southwest toward Porta Capena (Vicus Camenarum); a third extended south toward the Valle della Ferratella; a fourth went north toward the valley of the Colosseum (Vicus Capitis Africae).

The other important major thoroughfare was Via Tusculana, corresponding more or less to the modern Via dei SS. Quattro Coronati. This street ran south of the Ludus Magnus and left the city through the Servian Wall at Porta Querquetulana, where the Church of the SS. Quattro Coronati is located. Farther ahead, beyond its intersection with Via Caelimontana, it passed through the postern gate in the Aurelian Wall near S. Giovanni in Laterano and headed toward Tusculum (located above Frascati).

ITINERARY

THE TEMPLE OF DIVUS CLAUDIUS Ruins of the temple dedicated to the deified Claudius can still be seen on the western end of the Caelian, facing the Palatine. The temple may have been built on the site of Claudius’s private domus, perhaps near the ancestral home of the Gens Claudia. Immediately after the emperor’s death in AD 54, his wife Agrippina began construction of the site, but this was partially demolished by Nero. Demolition was limited to the temple proper, while a monumental nymphaeum was added to the terrace wall—which remained intact—on the east, an alteration that transformed the foundation into a dramatic backdrop for the gardens of the Domus Aurea. The huge fountain stood at the far end of Nero’s urban villa, according to Martial (Sp. 2.9–10).

After Nero’s death, Vespasian rebuilt the temple, which rose on top of an impressive rectangular platform (180 × 200 meters), formed by massive retaining walls that are partially preserved. A portion of the western side, visible within the bell tower (on the southwestern corner) and in the Convent of SS. Giovanni e Paolo, belongs to the oldest phase of the monument. It consists of a group of interconnecting rooms, two stories high, resting against a series of superimposed walls (a good 6.10 meters thick altogether), behind which run two parallel corridors. The facade is fashioned entirely of travertine blocks, many of which are still rough-hewn, following the characteristic “rusticated” style typical of the Claudian period (like Porta Maggiore, the arches of the Aqua Virgo in the Campus Martius, and the porticoes of the Port of Claudius). This part of the complex was constructed immediately after the death of the emperor. The piers between the arches on the facade are decorated with Doric pilasters, of which only the capitals are finished; these are surmounted by a heavy architrave. The present ground level corresponds to the original second floor, but exploration below this has brought to light a section of the ground floor. The radial walls within the rooms were made of brick, and the ceilings were vaulted; originally similar walls closed the arches as well, leaving openings for windows. At the center of the western side, a projecting platform supported the stairway leading to the temple; brick remains of the platform survive, incorporated in a modern building.

The northern side, of which very little survives, also consisted of a row of rooms built against a back wall. On this side, a short distance from the foundation, a terraced brick structure descended in the direction of the Colosseum; this was probably a large cascading fountain. From this side comes a large marble fountain head in the form of a ship’s prow with a boar’s head (now in the Museo Nuovo Capitolino), whose mid-first century AD date coincides with that of the associated building, unless it is a late Neronian addition.

Fewer remains survive on the building’s south, where the hill was higher and accordingly where there was little need for structural support.

The eastern side is the most monumental and best preserved of all, and from this the full extent of Nero’s modifications of the building are most clearly evident. This side was excavated in 1880 during the building of Via Claudia, which it follows for its entire length. It consists of a large brick wall with a series of niches and a larger chamber at the center. This enormous nymphaeum, originally equipped with fountains, is separated from the embankment to its rear by an empty space. A colonnaded porticus probably ran in front of the structure, with arches corresponding to the niches; it may have been designed to conceal some of the construction’s anomalies that are easily observable even today. The entire facade must have been finished with rich sculptural decoration.

No trace of the temple survives above the platform foundations. Fortunately, however, a fragment of the Severan Marble Plan partially fills in the gap. From this source, we know that the temple was prostyle hexastyle, with three columns on the sides. A garden occupied the rest of the area, which was probably enclosed within a porticus.

THE AREA BETWEEN S. GREGORIO AND VILLA CELIMONTANA The street that ascends between the churches of S. Gregorio and its three chapels on the right and SS. Giovanni e Paolo on the left follows the course of an ancient road. Its present name is probably the original one, Clivus Scauri, whose existence is attested not only in medieval sources, beginning in the eighth century, but even by an Imperial inscription. Construction of the street can thus be assigned to a member of the family of the Aemilii Scauri, thought to be M. Aemilius Scaurus, censor in 109 BC.

The street has preserved much of its ancient appearance, flanked here and there by Imperial period residences whose facades, interconnected by medieval arches that span the road, have been preserved to a remarkable height. On the left, an important group of ancient buildings is incorporated in the basement of the Church of SS. Giovanni e Paolo, but the street’s right-hand side contains a building complex of some interest as well.

Various ruins are scattered about the area surrounding the Church of S. Gregorio (FIG. 56:1): a section of a cryptoporticus, under the custodian’s house to the right of the church; the remains of a multistory residential structure, dating to the beginning of the third century AD, under the Chapel of S. Barbara; a portion of a tufa wall in opus quadratum applied as facing for a concrete core associated with the remains of a Republican public building, located to the right of the Oratory of S. Silvia. Farther up, behind the Oratory of Sant’Andrea, lies an apsidal basilical hall, whose masonry dates it to a rather late period. The building has been identified as the library of Pope Agapitus I (535–36); we know of its existence from a letter of Cassiodorus (De institutione divinarum litterarum, praef.) and from the dedicatory inscription copied by the author of the Einsiedeln Itinerary.

A little farther ahead, along the Clivus Scauri, another building can be seen that was probably part of the same complex. The traces of three doors, now blocked, are still visible on the brick facade facing the road. Remains of another large brick building, dated to the beginning of the third century AD, are distinguishable in Piazza dei SS. Giovanni e Paolo on the right, essentially a row of tabernae. Traces of a second floor can be discerned.

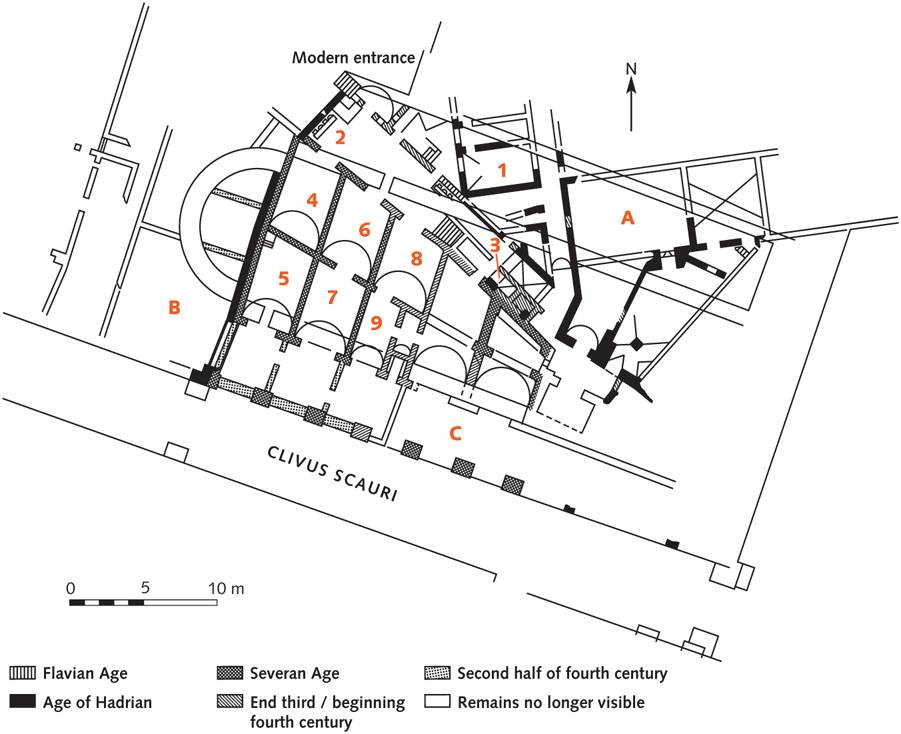

THE HOUSE OF SS. GIOVANNI E PAOLO Along the northern side of the Clivus Scauri lies the Church of SS. Giovanni e Paolo, which sits above and in part reuses several residences of the Imperial age (FIG. 56:2). The basilica opens onto a square from which an ancient street began, running north along the side of the Temple of Claudius. Another street, parallel to the Clivus Scauri on the north, bordered the residential area to which the remains under the basilica belonged (FIG. 57).

FIGURE 57. Plan of the remains under the Church of SS. Giovanni e Paolo. A,B,C The three original houses. 1 Bath building? 2 Nymphaeum with large wall painting. 3 “Confessio.” 4 Room with painting of youths and garlands. 5,7,9 Shops. 6,8 Back rooms.

Two houses stood southwest of the church: to the right of the apse, a large wall in opus mixtum of the second century AD is preserved to a height of three stories (B); a few remains of the other can be seen at the end of the right aisle (the large fresco of the nymphaeum in the entrance court, which will be treated below, covers an exterior wall of this second house). The left side of the church incorporates the facade of the second-century house located along the Clivus Scauri, which for this reason has been exceptionally well preserved; it was only partially covered by the medieval arches that spanned the street at this point (C). The ancient building was adapted to its new function by cutting the facade to half the height of the second floor and blocking the windows and the six arches at ground level.

The house had two entrances (corresponding to the two central arches), one of which (9) led directly to the ground floor, while the other led to the upper floors by means of a stairway. The windows were arranged in two nearly symmetrical groups on either side of a central axis—thirteen windows on the first floor above ground level, twelve on the second. A series of tabernae opened onto the porticus that fronted the ground floor.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, archaeologists found two large multistory residential properties below the church (one of these is associated with the facade described above). The two dwellings were separated by an alley (2), which was later transformed into an elaborate nymphaeum. The house situated further to the northeast (A) originally faced both the road parallel to the Clivus Scauri and the street perpendicular to it that ran along the Temple of Claudius; one of its shorter sides also faced the Clivus Scauri. In its present state, the building can be dated to the reign of Hadrian on the basis of brick stamps, although the structure reveals earlier phases, dating back at least to the Flavian period. The rooms that have been excavated are concentrated under the right aisle of the church, cut by the foundation walls of the colonnade that separated the aisle from the central nave.

The ground floor of the structure consisted of large rooms, almost perfectly oriented to the cardinal points, which were originally decorated with stuccos, paintings, and polychrome wall mosaics. The ground descended suddenly toward the north, thus creating space for several rooms that were below ground level in relation to the aforementioned rooms but occupied ground level on the side facing the valley. These rooms constituted a small private bathing facility (1); one of the rooms had a tub, and another a terracotta basin (labrum).

The best-preserved house (C) is below the basilica’s central nave and left aisle. Its facade, which forms the church’s left side, is perfectly preserved along the Clivus Scauri. This house, whose site was previously occupied by an older building, was separated from the other (A) by means of the narrow courtyard (2). This space was transformed, certainly during a second phase, into a rich nymphaeum and was at that time equipped with a masonry base with alternating square and semicylindrical niches, visible in two points—in front of room 8 and on the short western side. The new configuration featured fountains with special effects, while the floor was paved with a polychrome mosaic made of large tesserae. At the center there is a large well that was later raised to the level of the church floor. The walls of the room were decorated with lavish paintings. On the right, traces of a procession of erotes on sea monsters can still be seen. But the most remarkable section occupies the upper part of the short western side: an imposing fresco (5 meters long, 3 meters high) that may represent Proserpina’s return from Hades.

At the other end of the courtyard, beyond the foundation wall of the church’s interior colonnade, lies a large stairway abutting the northern wall of the house; this too belongs to a second phase. Thus the building, an insula of several stories subdivided into apartments, underwent extensive remodeling (possibly in the middle of the third century), its ground-floor level having been considerably lowered, and was transformed into a deluxe home; a similar process can also be observed in numerous houses in Ostia. The nymphaeum evidently dates to this second phase.

The courtyard of the nymphaeum leads to the ground-floor rooms that lie between it and the Clivus Scauri. Rooms 5, 7, and 9 were originally tabernae that opened onto the exterior porticus, which the addition of partition walls at a later period transformed into anterooms. Rooms 4, 6, and 8 opened onto the courtyard and from here provided access to the house farther to the north, while a stairwell in the small passageway (3) led to the upper rooms. Rooms 4, 6, and 8 had access to both the shops and the courtyard. Room 4, immediately adjacent to the large fresco in the nymphaeum, contains a remarkable painting on a white background, depicting youths holding up a vegetal festoon, with peacocks and other large birds in between. Vines and tendrils, among which erotes and birds flit about, are depicted in the vault. The floor was paved with marble slabs, removed in antiquity, although traces of the paving remain. This remarkable decoration seems to be contemporary with that of the nearby nymphaeum.

Rooms 8 and 9 contain decorative work that is later, attributable to the first half of the fourth century AD, imitating, for the most part, the rich inlaid work of polychrome marble. In the “Aula dell’orante” (8), the painting, also dated to the fourth century, is richer and very well preserved, except for the central part of the vault, which is lost. A heavy frieze of acanthus tendrils runs above the typical decoration, which imitates marble crustae; above this rises the vault, decorated with a circular motif divided into twelve sections, containing, among other decorative elements, paired sheep as well as male figures holding scrolls. The figure of a man praying—shown in typical fashion with his arms outspread—appears in a lunette; the painting reveals the Christian character of the house in this period.

Of considerable interest for the history of the Church is the small confessio halfway up the stairway in the courtyard (3). This small niche, decorated with frescoes dating to the second half of the fourth century AD depicting Christian martyrs, was situated in a position that corresponds with an opening in the church’s central nave. The frescoes, in two registers, covered three sides of the niche, onto which the fenestella confessionis opened. The sides of the confessional grating are decorated with two figures dressed in the pallium; below them a male figure prays while two individuals prostrate themselves at his feet. The most interesting scenes are those on the right: three figures—two men and one woman—marching, escorted by two others (possibly soldiers); the beheading of the three is depicted in the panel below. In the natural tufa of the area beneath the staircase, below the niche, are three openings that have been identified as tombs.

It would be difficult not to associate these very old representations with the account of the passio of Saints John and Paul. Yet, even if the titular saints of the church could have been added later, the similarity of the painting to the account of the martyrdom of Crispus, Crispianus, and Benedicta at the time of Julian the Apostate is striking. The bodies of the latter three might have been buried in the house, which, from the third century on, belonged to a Christian named Byzas, who was supposed to have given it to the Church, transforming it into a titulus. The presence of Christian subjects in frescoes datable to the beginning of the fourth century; the probable use of the first floor of the house as a meeting place, whose form and dimensions resemble those of the later basilica; the frescoes of the second half of the fourth century (and thus not long after the events they narrate), in which the martyrdom of two men and a woman is depicted—all of this coincides quite closely with, and thereby confirms, what we know of the tradition.

The basilica that was subsequently built incorporated the titulus and the adjacent secular buildings. Construction must have begun around 410, after which the work was carried out in several fairly close phases. The nave (44.30 meters long and 14.68 wide) and the aisles (7.40 meters wide) were separated by thirteen arches supported on twelve columns. The foundations of the colonnade rested on the preexisting buildings in such a way that only part of the ground floor of the titulus remained accessible. A semicircular apse, with four large windows, was added to the nave.

A small museum contains the material found during the excavations.

THE ARCH OF DOLABELLA AND THE AREA AROUND S. MARIA IN DOMNICA Via di S. Paolo della Croce begins at Piazza dei SS. Giovani e Paolo and follows an ancient road that is the continuation of the Clivus Scauri. After skirting Villa Celimontana, the street passes under a travertine arch that supports the Neronian Aqueduct, whose arches continue beyond the wall on the left in the adjacent gardens. A barely legible inscription preserved on the attic of the arch’s exterior facade names the consuls of AD 10:

P. Cornelius P.f. Dolabella / C. Iunius C.f. Silanus flamen Martial(is) / co(n)s(ules) / ex s(enatus) c(onsulto) / faciundum curaverunt idemque probaver(unt) (P. Cornelius Dolabella, son of Publius, and Gaius Junius Silanus, son of Gaius, flamen of Mars, consuls, by decree of the Senate saw to the construction and inspection [of this monument]).

On the right side of the arch, below the brick wall, the beginning of a structure in blocks of Grotta Oscura tufa, closely joined to the arch, can be distinguished. The remains surely belong to the Servian Wall and, accordingly, the extant arch must be one of Augustus’s reconstructions of the wall’s gates (almost certainly Porta Caelimontana), similar to the reconstruction of Porta Esquilina and probably many others.

The square now occupied by Villa Celimontana rests upon large ancient walls, mostly of Flavian date, whose remains are visible principally on the piazza’s southern side. Within the perimeter of the villa, a short distance from its entrance off the Piazza della Navicella, lay the barracks of the Fifth Cohort of the Vigiles, seen in 1820, 1931, and again in 1958 (FIG. 56:3). The identification is confirmed by inscriptions, two of which are still inside the villa. The remains belong to the Trajanic period.

In 1889, a building was discovered on the opposite side of the piazza, toward the Colosseum and within the grounds of the military hospital, whose mosaic floor had curious designs intended to ward off the evil eye. An inscription in the mosaic names the building: Basilica Hilariana. A base found among the ruins supported a statue of the basilica’s founder, Manius Publicius Hilarus, a pearl merchant; the statue was dedicated to him by the college of dendrophori, worshipers of Cybele, to which Hilarus belonged. Excavations conducted between 1987 and 1989 have uncovered almost the entire building, which was constructed during the Antonine period (ca. AD 145–55) and restored in the first half of the third century. It is possible that the arbor sancta mentioned by the Regionary Catalogues as lying between the Caput Africae and the Castra Peregrina—that is, more or less in this area—could be a reference to the Basilica Hilariana and to the building of which the basilica formed a part, and which must be regarded as the headquarters of the dendrophori. Veneration of a sacred pine in fact played a role in the cult of Cybele. A recently excavated four-sided structure at the center of the courtyard probably housed the pine that was ritually transported to the Temple of the Magna Mater on the Palatine every year on 22 March.

An extraordinary residence dating to the second half of the third century was also discovered near the basilica; it belonged to a Gaudentius, as a mosaic inscription indicates, during a late phase of the building. This Gaudentius can with great probability be identified as a senator of the period between the end of the fourth and the beginning of the fifth century AD, and a friend of Q. Aurelius Symmacus, whose residence was certainly nearby.

THE LATERAN The Lateran forms only a marginal part of the Caelian, located inside the Aurelian Walls where Via Caelimontana, Via Asinaria, Via Tusculana, and another anonymous ancient street that corresponds to the modern Via dell’Amba Aradam converge (FIG. 58). A series of excavations, both early and recent, provides a sufficiently clear explanation of the topography of the area.

Excavation below the Ospedale di S. Giovanni (Sala Mazzoni) undertaken several decades ago (1959–64) brought to light various phases of a building in use between the first and fourth centuries AD. This could well be the villa of Domitia Lucilla, the mother of Marcus Aurelius, where the future emperor spent his youth. Among other things, a peristyle was found, at the center of which was a basin that was replaced in the course of the second century by a pedestal. Several reliefs representing the Temple of Vesta and the Vestals probably belong to this. It has been suggested—probably incorrectly—that this was the original base of the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, now on the Capitoline. As is well known, this monument originally stood in the vicinity of the Lateran, where it remained until 1538, when it was transferred to the Capitoline.

FIGURE 58. Plan of the area around the Lateran.

On the other side of Via dell’Amba Aradam, within the triangle formed by it and Via dei Laterani, an excavation undertaken a few years ago during construction of the headquarters of the Istituto Nazionale della Providenza Sociale revealed a group of buildings at a depth of 10 meters that descended gradually on terraces. Two different complexes dating to the Julio-Claudian period and with second-century AD restorations were identified here. At the beginning of the fourth century, these were then combined into a single complex containing a large corridor (5 meters wide) that was closed on the north and pierced on the south by wide windows. A spacious exedra opened onto the corridor, of which only a section of 27 meters remains, presumably at its center. Some have suggested that these buildings should be identified as the houses of the Pisones and Laterani, confiscated by Nero. The later merger of these houses into a single residence is thought to have constituted the Domus Faustae, the home of Maxentius’s sister and Constantine’s wife.

The remains of a nymphaeum were found at a depth of 7.50 meters a little farther to the north, at the intersection of Via dell’Amba Aradam and Via dei Laterani. It consisted of a rectangular room flanked by two smaller rooms and ending in an apse, whose back wall contained a rectangular niche. Remains of glass mosaics belong to the building’s first phase, the Julio-Claudian period. Later modifications were introduced and paintings added; those in a room to the right of the apse are well preserved. These improvements probably date to the third century AD. The baths, whose central hall is still preserved southeast of the Lateran Baptistry and which can be dated to the first half of the third century AD, are reasonably associated with these buildings.

Remains of a villa of the first century AD were discovered on the other side of Via Tusculana beneath the Baptistry; this was replaced by a bath complex at some point between the reigns of Hadrian and of Antoninus Pius. The building was in turn entirely rebuilt under Septimius Severus and Caracalla. The same phases can be found in the bath structure located farther to the southwest, mentioned above. The relationship between these two buildings is not clear.

The most remarkable complex of the area, however, was discovered between 1934 and 1938 underneath the Basilica of S. Giovanni in Laterano. A house of the third century, trapezoidal in form, had already been brought to light in the course of work undertaken in 1877–78 by Vespignani. The structure is located very close to, and in part underneath, the church’s old apse. The floor mosaics of the courtyard have been partially preserved.

The remains of a wealthy house of the first century of the Empire were discovered beneath the nave and aisles of the church and under a part of the cloister; it was built on terraces sloping downward from northwest to southeast and situated at a slightly oblique angle to Via Tusculana. The rich Fourth Style decoration of Neronian date makes it likely that this belongs to the Lateran estate, seized by Nero in AD 65. At the end of the second century—probably sometime after AD 197—this residence, which lies 5.55 meters below the floor of the church, was replaced by the second barracks of the equites singulares, the mounted guard of the emperor (Castra Nova Equitum Singularium) (FIG. 56:7). The complex, erected by Septimius Severus, was, like the house, also oriented along a north-south axis. The praetorium, the residence of the commander, was probably located between the second and third spans of the basilica. It comprised a courtyard, 15 × 21 meters, closed on the north by a porticus of piers, on the south by the camp’s sacrarium, and on the other two sides by rooms belonging to the officials; an inscription dated to AD 197 comes from one of these rooms. Further west lie two long sections, each consisting of series of facing rooms (under the fifth span and transept) that served as housing for the troops. The mosaic flooring, with geometric designs in black and white tesserae, and remains of wall paintings are preserved in many of the rooms.

At the beginning of the fourth century all of these structures were cut off to make room for the basilica. The apse of the church, as mentioned above, encroached upon a house situated west of the barracks. The total length of the building can be reconstructed as 99.76 meters, the central nave measuring 90.55 meters. It was thus somewhat smaller than St. Peter’s Basilica. The basilica proper consisted of five aisles; the two exterior aisles were shorter in order to make space for two chambers that formed a transept.

The date of the basilica can be assigned to the first years after the battle of Saxa Rubra. The construction was probably completed in a few years, between 314 and 318. Dedication must have taken place on 9 November 318. Accordingly, this is the oldest Christian basilica in Rome.

TOMBS ON THE CAELIAN Numerous tombs, the oldest of which dates to the end of the fourth century BC, lined Via Caelimontana. Several funerary monuments have appeared at various times within Villa Wolkonski, a property of the British Embassy. The tombs, of various periods, have almost completely disappeared.

Only the columbarium of Tiberius Claudius Vitalis, discovered in 1866 near the lodge of the villa, is extant. The structure was made of brick in a style commonly found between the first and second centuries AD; it originally had three stories, 9 meters high altogether, but is preserved to a height of 5.40 meters. The marble inscription, surrounded by a frame, is preserved above the door, which opens off center on the left. The dedicatory inscription, erected by an Imperial freedman and architect named Tiberius Claudius Eutychus, mentions Tiberius Claudius Vitalis, his father of the same name (also an architect), his mother Claudia Primigenia, and his sister, Claudia Optata. The interior consists of three superimposed rooms (4 × 3 meters) with mosaic flooring. The walls of the first two rooms contain three rows of loculi, in each of which are three or more cinerary urns. The third floor has no loculi and thus was probably intended for the funerary cult. Given its identification with a freedman of Claudius, the tomb should be dated somewhere between AD 41 and 80.

Further on, at the intersection of Via Statilia and Via di S. Croce in Gerusalemme, lies a notable group of Republican tombs, discovered in 1916 during an enlargement of the road and now protected by a shed. The first one on the left, with a facade of tufa blocks containing a central door, may be the oldest; the door is flanked by two round shields, fashioned out of the same blocks that form the facade. The funerary chamber is very small, partially cut in the rock and roofed with an irregular vault in opus caementicium. The inscription identifies the owners as a P. Quinctius, bookseller and freedman of Titus, his wife, and his concubine. The lack of a cognomen and the rather archaic appearance of the monument point toward a date of around 100 BC or a little earlier. The next tomb has two chambers with adjacent doors, decorated with busts of the dead (a woman with two men on the left, two women on the right). This is probably one of the oldest examples of the use of portraits of the deceased on tomb facades. The inscriptions, altered at some point, name six persons; the fact that several of the dead are listed with cognomina suggests a date a little later than the previous tomb, that is, around the beginning of the first century BC. Next to these are a columbarium, almost completely destroyed, and a monument in the form of an altar that was later enlarged in opus reticulatum. The inscription of the latter assigns the monument to two Auli Caesonii, probably brothers, and a Telgennia. This small group of tombs allows us to follow at close hand the evolution of funerary monument types from the chamber tomb (the oldest belonging to P. Quinctius) to the isolated monument (the latest belonging to the Caesonii), between the end of the second and the beginning of the first century BC.

FIGURE 59. TheQuirinal, the Viminal, and the Via Lata. 1 Porta Sanqualis. 2 Temple of Serapis. 3 Baths of Constantine. 4 Altar of the Neronian fire. 5 Imperial residences. 6 Complex of the Horti Sallustiani. 7 Tomb of Lucilius Paetus. 8 Buildings under S. Pudenziana. 9 Porticus Vipsania. 10 Hadrianic insulae. 11 Temple of the Sun. 12 Villa of Lucullus. 13 Barberini Mithraeum. 14 Baths of Diocletian. 15 Castra Praetoria.