AVENTINE, TRASTEVERE, AND THE VATICAN

HISTORICAL NOTES

The Aventine is Rome’s southernmost hill and the one closest to the Tiber. The hill’s steep slopes, which isolated it to a large extent from its surroundings, and its proximity to the river had a profound influence on its history, which was closely bound with the struggle of the plebs. Its original name may have been Mons Murcus, a name reflected in the nearby Vallis Murcia and in an ancient shrine belonging to the goddess Murcia, who was probably later identified with Fortuna Virilis and Venus Verticordia.

We do not know when the Aventine was first inhabited. According to one plausible tradition, Ancus Marcius introduced people from Ficana, Tellenae, Medullia, and Politorium—towns that he conquered and destroyed. Later, because of its particular position, the Aventine became a quarter that was primarily mercantile, frequented by foreigners, and thus outside of the pomerium, despite the fact that the hill was already included within the Servian Wall in the sixth century BC, as the remains near S. Sabina prove. Only during the reign of Claudius was the hill brought within the pomerium. Servius built a temple of Diana here (FIG. 90:1), apparently taking as his model the sanctuary of Artemis in Ephesus. The cult may have been introduced to replace that of Diana Aricina as the federal sanctuary of the Latins, unless, as is more likely, the latter was inspired by the Roman sanctuary. The temple stood alongside that of Minerva (FIG. 90:2), occupying the center of the hill and corresponding, more or less, to the present-day Via S. Domenico. A fragment of the Severan Marble Plan represents both buildings. The Temple of Diana shown on the plan has the appearance it assumed following its reconstruction by L. Cornificius after 36 BC: a large octostyle peripteral temple with two rows of columns—Greek in style and quite similar to the Artemision of Ephesus. It was located at the center of a large porticus that also had two rows of columns. Farther to the north was the Temple of Minerva, founded in the third century BC, which functioned as the center for the trade guilds—in particular for the guild of writers and actors from 240 BC on. The history of the Aventine thereafter was informed by these precedents: the inhabitants of the hill, from different points of origin—often foreigners—ultimately formed the plebeian class, giving rise to the long struggle between patricians and plebs that began with the Republic. Following the secessions of the fifth century, the situation was settled only at the beginning of the third century, when the two social groups were given political parity.

Other temples were subsequently built near these older ones; for example, the sanctuary of Ceres, Liber, and Libera at the foot of the hill, headquarters of the plebeian aediles and center of the plebs’ political and economic organization. Moreover, various foreign cults were recorded as evocati (summoned) from enemy cities with a typically Roman rite: the Temple of Juno Regina, founded by Camillus after the destruction of Veii in 396 BC; the temples of Consus and Vertumnus, founded respectively by L. Papirius Cursor in 272 BC and by M. Fulvius Flaccus in 264 BC after the conquest of the Volsinii. The sanctuaries of Luna, Iuppiter Liber, and Libertas should also be mentioned. In 456 BC, with the promulgation of the Lex Icilia, the entire hill was declared public property and distributed to the plebs so that they might build homes there. From that time forward, the quarter continued to attract inhabitants and ultimately became so densely populated that during the Augustan period practically no usable space was available for public buildings. The plebeian associations of the hill were still in force during the second century BC when, in 122 BC, Gaius Gracchus took refuge there with his friends and partisans for their final stand. The historical account of this event allows us to reconstruct the position of the most important cult buildings. At first, Gaius took refuge in the Temple of Diana, from where he moved on to the nearby Temple of Minerva. Forced from here too, he pushed forward to the westernmost point of the hill, at the Temple of Luna, where he injured his ankle jumping down from the podium. After descending from the Aventine, he passed through the Porta Trigemina and across the Pons Sublicius, while some of his friends sacrificed their lives trying to impede his pursuers. Finally, after he reached the Janiculum, the tribune gave up all hope of survival and committed suicide in the grove of Furrina.

During the Empire, the Aventine lost its associations as a working-class and commercial quarter and was transformed into an aristocratic neighborhood. The poorer inhabitants moved south to the plain near the Emporium and to the right bank in Trastevere. In fact, whereas during the Republic, with the exception of the domus of the Sulpicii Galbae, we know only of the houses of some poets (Naevius, Ennius), the situation changes radically under the Empire, when mention is made of the houses of the emperor Vitellius, of L. Licinius Sura, the friend of Trajan, and of Trajan himself before he became emperor. The region’s status as an affluent quarter was probably a factor in its near-total destruction at the hands of Alaric, when the Goths vented their fury and sacked Rome and the houses of the wealthy inhabitants in particular. In addition to the archaeological evidence, the letters of St. Jerome record this destruction. Consistent with its social character, the Aventine was the site of two bathing establishments that must have been particularly elegant: the Thermae Suranae (FIG. 90:4), built by Licinius Sura near his house or perhaps by Trajan in the house that was bequeathed to him by his friend, and the Thermae Decianae (FIG. 90:6). Popular eastern cults are less often represented here than they are in Trastevere. We know, however, of a sanctuary of Iuppiter Dolichenus, commonly referred to as the Dolocenum, and a Mithraeum under the Church of S. Prisca (FIG. 90:5). During the first centuries of the Republic, commercial activity took place in the Forum Boarium near the northern slope of the hill; from the beginning of the second century BC, it shifted to the plain to the south, where the new river port (Emporium), the Porticus Aemilia, the large warehouses and stores behind the latter (Horrea Galbana, Lolliana, Aniciana, Seiana, Fabaria), and the general bread market (Forum Pistorium) were built. The name Marmorata, which the whole area continues to be called, alludes to one of the most important items that was unloaded here: marble. Enormous quantities of quarried blocks have been discovered in the area at various times.

Behind these buildings rises Monte Testaccio (Mons Testaceus)—the hill of potsherds—30 meters high, created entirely from the accumulation of amphoras dumped here from the nearby port. Though largely unexplored, it constitutes an archive of Rome’s economic history.

The last of the fourteen Augustan Regions included the neighborhoods on the right bank of the Tiber and Tiber Island: Trastevere to the south, the Janiculum in the middle, and the Vatican to the north. Until the reign of Augustus, this area remained formally outside of the city; it lay outside the pomerium until Vespasian came to power.

The Janiculum forms a natural bastion for the city in the direction of Etruria; rising opposite the Pons Sublicius, which tradition assigns to King Ancus Marcius, it was vital to the city’s defenses. Its important role can be observed in the custom, certainly of great antiquity, of raising a red flag on the hill as a signal that all was secure when elections were being held in the Campus Martius; the citizens were in a dangerous position at that time, being outside of the walls. The district contained several fairly old sanctuaries, such as that of Fors Fortuna, at the first milestone of Via Portuensis, the ancient Via Campana. Servius Tullius was believed to have founded the shrine, near which the consul Spurius Carvilius erected a second sanctuary in 293 BC, dedicated to the same divinity. Another temple, also dedicated to Fors Fortuna, stood at the sixth milestone of the same road, near that of Dea Dia, in the care of the priesthood of the Arval Brothers. Remains of this sanctuary were seen in the nineteenth century; excavation of the site is now in progress.

Initially the occupation of the right bank must have been limited to the cultivation of arable land by private citizens, as can be deduced from the mention of the Prata Mucia awarded to Mucius Scaevola and of the Prata Quinctia, between the Janiculum and the Tiber, that belonged to the celebrated Cincinnatus. Famous Romans were buried on the Janiculum: the poets Ennius and Caecilius Statius, as well as the mythical king Numa.

From the end of the Republic, Trastevere came to be filled with utilitarian buildings and private residences; the latter were associated particularly with the workers and small businessmen drawn by the economic activity of the port and the related services in the vicinity. Inscriptions dating to the last decades of the second century BC, discovered in the middle of the nineteenth century during the construction of a tobacco factory in Piazza Mastai, attest to the presence of a Pagus Ianiculensis in the area.

We can deduce from inscriptions and other literary sources that by the Imperial period Trastevere had already become a vast neighborhood, consisting of seventy-eight vici—more than twice the number of Region XI, the second in importance. This was the home of potters, craftsmen specializing in leather, ivory, and ebony, millers who worked at watermills on the slope of the Janiculum (FIG. 91:6), porters who toiled in the innumerable warehouses and stores, and furnace operators at the brick factories of the Montes Vaticani.

The working-class character of the neighborhood is particularly evident in the cults found there; excluding the oldest cults—Dea Dia, Fors Fortuna, Furrina, Fons, Divae Corniscae, Albionae—the number of eastern divinities is particularly striking: Dea Syria, Hadad, Sol in Trastevere, Isis and Cybele in the Vatican. The latter’s temple, the Phrygianum, was near the facade of St. Peter’s, while a sanctuary of the Syrian divinities was discovered in 1906 on the slope of the Janiculum, although the phase of this sanctuary as we know it more closely resembles a syncretic cult (FIG. 91:7). Important colonies of Syrians and Jews formed here from as early as the end of the Republic. The oldest Jewish cemetery in Rome was discovered in the vicinity of Porta Portese. This district, which preceded the ghetto on the left bank, must also have contained the oldest synagogue in the city.

As is always the case in regions on the periphery, the unhealthy lowlands were occupied by the hovels of the poor, while the slopes and peaks of the hills and the banks of the Tiber were dotted with suburban villas and gardens. Cicero mentions a considerable number of affluent residences in several letters of 45 BC. One of the most important villas belonged to the infamous Clodia—Catullus’s Lesbia—sister of the tribune who was Cicero’s archenemy. Some have identified the Villa della Farnesina, an imposing Augustan building that lay along the bank of the river, as Clodia’s estate (FIG. 91:10); its splendid pictorial decoration was removed and is now in Palazzo Massimo. (The building was unfortunately destroyed immediately after its discovery in 1880.) It is more likely, however, that the villa belonged to Agrippa, who had substantial landholdings in the nearby Campus Martius and the Vatican region. His daughter Agrippina, the mother of Caligula, probably inherited the Vatican Horti from him. Near the villa were warehouses for wine, identified by an inscription as the Cellae Vinariae Nova et Arruntiana (FIG. 91:9), and the important “Tomb of the Platorini” (FIG. 91:8), which in fact belonged to an individual named Artorius Priscus and dates to the first half of the first century AD; it was dismantled and reconstructed in a hall of the Museo delle Terme. The most important estate of Trastevere, however, was Caesar’s, which must have extended into an area that was later occupied by the Naumachia Augusti, located between the Tiber, the first milestone of Via Campana-Portuensis, and the slope of Monteverde. Caesar bequeathed the gardens to the people of Rome.

There were two large parks in the Vatican: the Horti of Agrippina, roughly between the Tiber and St. Peter’s, where Caligula later built his Circus, and the Horti of Domitia, in the area around Hadrian’s Mausoleum and Palazzo di Giustizia (FIG. 92).

Traffic movement on the right bank of the Tiber was dependent on two fairly old streets, originally outside of the city, that ran toward the oldest bridge, the Pons Sublicius. The bridgehead was located just downstream of the later Pons Aemilius (Ponte Rotto). From this point, Via Campana-Portuensis veers to the south and Via Aurelia to the west. The former ran toward the salt pans at the mouth of the Tiber and later, after the construction of artificial ports by Claudius and Trajan, was the first segment of Via Portuensis, whose course was more direct than Via Campana, which followed the bends in the river. Ancient sanctuaries, such as those of Fors Fortuna and Dea Dia, flanked the road. A fragment of the Severan Marble Plan represents a section of the street, on either side of which stand large warehouses, and a round building on a square base, possibly the Temple of Fors Fortuna, at the first milestone. A large rectangular open area is probably the Naumachia Augusti. A building with two courtyards, located near Piazza S. Cosimato, is certainly a barracks, probably the Castra Ravennatium, the quarters of the sailors stationed with the fleet in Trastevere. The sailors probably served as harbor police, as well as overseeing preparations for mock sea battles (the naumachiae).

The course of Via Aurelia is much better known. It was probably built in 240 BC, though it was certainly preceded by an older road that led from the cities of southern Etruria to the ford of the Tiber. The road corresponds exactly to the modern course of Via della Lungaretta and can be followed up to Piazza di S. Maria in Trastevere. From here it ascended the Janiculum and left the city from Porta Aurelia. In the stretch lying roughly between Piazza del Drago and Piazza Tavani Arquati, the road passed over a low and swampy area on a viaduct, supported by arches made of tufa in opus quadratum that rose to a height of more than 5 meters. This impressive work, elements of which have been seen at various points, probably dates back to the middle of the second century BC, when the Pons Aemilius was completed. Later, at the beginning of the Empire, the surrounding level was raised; large utilitarian structures of brick and travertine piers were built up against the viaduct.

FIGURE 91. Map of Trastevere. 1 Temple of Aesculapius on Tiber Island. 2 Buildings under S. Cecilia. 3 Buildings associated with the Annona documented by the Severan Marble Plan. 4 Excubitorium of the Vigiles. 5 Buildings documented by the Severan Marble Plan. 6 Watermills. 7 Syrian sanctuary. 8 “Tomb of the Platorini.” 9 Cellae Vinariae Nova et Arruntiana. 10 Villa della Farnesina.

Another street, parallel to Via Aurelia, splits off from this just before Porta Aurelia and, following the course of Via Luciano Manara for a distance, reaches the Tiber, passing south of S. Cecilia (FIG. 91:2). A bridge was built in conjunction with this road, traces of which were seen a little upstream of the Ospizio di S. Michele and which is usually identified as the Pons Probi. Another ancient road, west of and parallel to Via Portuensis, corresponds to the course of Via della Luce.

Yet another ancient road afforded passage between Trastevere and the Vatican. This broke off from Via Aurelia on the right at Sant’Egidio and from here went north, following the course of the present-day Via della Scala as far as Porta Septimiana; from here it passed between the Janiculum and Tiber, probably following the same course as Via della Lungara. It crossed the area where the archaic Prata Quinctia were located, as well as a swampy region called Codeta. A branch broke off from this street toward the Campus Martius, in conjunction with the Pons Agrippae, the modern Ponte Sisto.

Traffic in the Vatican moved essentially along two major roads (FIG. 92): Via Triumphalis, which ran from the Pons Neronianus directly toward Monte Mario, and Via Cornelia, which branched off from it to the left. The latter followed the course of present-day Via della Conciliazione and ran toward the Circus of Caligula, which it followed for its entire length.

It is uncertain whether the walls included any part of Trastevere during the Republic; it is likely, however, that an outpost was established on the Janiculum at the beginning of the second century BC. Vespasian’s enlargement of the pomerium must have extended to a small area of Trastevere, as the inscribed cippus found at S. Cecilia shows. The Aurelian Wall, on the other hand, enclosed a large portion of the region. There were three gates here: Porta Portuensis on the south, Porta Aurelia on the west, and Porta Septimiana—it is uncertain whether this was its ancient name—on the north.

ITINERARY 1

The Aventine and Emporium

THE AREA AROUND S. SABINA The Church of S. Sabina occupies the northwestern side of the Aventine in an area crossed by the Vicus Armilustri, corresponding to the present-day Via di S. Sabina (FIG. 90:7). Soundings taken beneath the church and its environs at various times, in particular in the years 1855–57 and 1936–39, have uncovered a series of remains dating between the archaic period and the end of the Empire.

In the nineteenth century, the area north of the church, at the edge of the modern garden, was explored. Important remains of the Servian Wall were discovered here, clearly revealing two successive phases: archaic in cappellaccio and early fourth century BC in Grotta Oscura tufa. At the time of construction of the wall in Grotta Oscura tufa, the cappellaccio blocks of the earlier wall were recut to create a level course that served as the new structure’s foundation. From this fact, it is clear that the cappellaccio wall represents an older phase. Various buildings were built very close to the walls. The oldest of these, with construction in opus incertum and mosaic floors into which colored stones were inserted, are second-century BC private residences. Later, from the end of the Republic, several buildings in opus reticulatum were built outside the walls, into which four openings were pierced to allow for passage between the outside and inside—an indication that the wall no longer served a defensive function. In the second century AD, several of these rooms were restored and used by a community dedicated to the worship of Isis, as attested by wall paintings and surviving graffiti. Reconstruction in brick during the third century AD transformed some of these rooms into a bath complex.

FIGURE 92. Map of the Vatican. 1 Meta Romuli and Terebintus Neronis. 2 Mausoleum of Hadrian. 3 Vatican necropolis. 4 Necropolis of the autoparco.

Soundings below the quadriporticus of the church (1936–39) revealed the presence of an ancient street that ran parallel to Vicus Armilustri on the west. Because its course follows the highest ridge of the hill, some have suggested that this street is the Vicus Altus cited in an inscription. A brick building with an interior courtyard, off which there were small rooms, stood along the first. The style of construction and the mosaics date the structure to the Augustan period at the latest.

The excavations that were undertaken directly underneath the basilica are even more important, revealing early Imperial residences with marble floors. Among other things, there appeared a small temple in antis with two peperino columns between the antae, certainly quite old (ca. third century BC). At the end of the Republic or at the beginning of the Empire, the spaces between the columns were closed with walls in opus reticulatum. Excluding the possibility that this was the Temple of Juno Regina, which is documented in the vicinity—the temple would have been built on a considerably grander scale—it may be one of several smaller sanctuaries in the area—perhaps the Temple of Iuppiter Liber or of Libertas, if these two did not actually constitute the same cult. The Temple of Juno Regina, with which the preceding was closely associated, as can be deduced from the fact that they share the same dies natalis, must have occupied an area corresponding to that of the church. Some remains found below the northern end of the basilica probably belong to the temple.

The Regionary Catalogues and other sources report the presence of a sanctuary of Jupiter Dolichenus on the Aventine, which, following various attempts to locate the site of the cult, can now be situated in an area not far from Sant’Alessio and S. Sabina. Discovery of the building, whose surface area spanned 22.60 × 12 meters, occurred in 1935 during construction of Via di S. Domenico. Only the long northern side and part of the short sides were excavated. The sanctuary, perhaps a courtyard originally, was part of a larger building that revealed an older phase, probably Augustan. It consisted of a hall preceded by an atrium and followed by a third room that was almost square. In the central and most important room, the remains of an altar were found, as well as a large inscription with a dedication to Jupiter Dolichenus commissioned by Annius Iulianus and Annius Victor. A remarkable number of statues, reliefs, and inscriptions was found in the building. The variety of the divinities that are represented underscores the syncretistic tendency of the cult, originally from Asia Minor, that associated itself with the principal divinity of the Aventine, among others; there is evidence that Diana was worshiped here, in addition to Isis and Serapis, Mithras, the Dioscuri, Sol, and Luna. All the material discovered in the sanctuary is now on display in the Capitoline Museums, in the Hall of the Eastern Cults.

The complex, originally open to the sky, dates to the reign of Antoninus Pius, after AD 138, as attested by brick stamps and an inscription bearing the date of AD 150. Stamps on the roof tiles provide evidence that it was roofed in the second half of the second century, and it was restored periodically, especially during the third century, when the cult must have reached its peak.

THE MITHRAEUM OF S. PRISCA AND THE THERMAE SURANAE The Church of S. Prisca is probably the oldest Christian cult site on the Aventine. It corresponds to the titulus of Aquila and Prisca, where St. Peter and St. Paul were supposed to have lodged. Excavations, begun in 1934 and resumed in recent years under the direction of Dutch scholars, have uncovered a rich Mithraeum that occupied the rooms of an older house (FIG. 90:5). Brick stamps date the building, situated north of the church, to around AD 95 or a little afterward. A quadriporticus on the building’s eastern side was transformed into a residence around AD 110, while a large apsidal nymphaeum was built to the south, in the area of an adjacent house. A building with two aisles was added on the south toward the end of the second century. The present church rests on this (perhaps the paleochristian titulus?); the Mithraeum was installed in another room during the same period. The latter was violently destroyed around AD 400, just before construction of the church, evidently by the Christians themselves.

The excavators believe that the original building was the (Domus) Privata Traiani, the house in which Trajan lived before he became emperor. There is another possible explanation, however. A fragment of the Severan Marble Plan representing the Thermae Suranae, adjacent to the slab on which the Temple of Diana was represented, shows that these baths were immediately northwest of S. Prisca, under the present-day Scuola di Danza; recent excavations have brought to light important remains of the complex (FIG. 90:4). On the other hand, the arches of the Aqua Marcia, which extended to the Thermae Suranae, passed directly through the area later occupied by the church. Therefore, identification of the late-first-century AD house as the residence of Licinius Sura seems more plausible; it was probably adjacent to the baths. We know from inscriptions that these baths were restored by Gordianus and again in AD 414 to repair damage incurred in the sack of Alaric, who thoroughly ravaged the Aventine.

On the fragment of the Severan Marble Plan that represents the baths, a peripteral temple, sine postico and certainly Republican, appears northwest of the complex. The position could well correspond to that of the Temple of Consus or of Vertumnus.

A stairway leads from the right aisle of the church to the Mithraeum. The nymphaeum with hemicycle is the first stop along the way—the site of a small museum in which material from the excavations is displayed. Of particular note are the magnificent representation of the Sun in opus sectile of polychrome marbles and the stucco heads—including that of Serapis—from the decoration of the Mithraeum. Several drums from large peperino columns (90 centimeters in diameter) have been reused in a small room nearby; they certainly came from a Republican temple somewhere in the vicinity, perhaps that of Diana. Other columns of the same sort are embedded in the wall to the right of the church’s facade.

Beyond the crypt of the church lies the room that precedes the spelaeum. In its earliest phase, this room functioned as an atrium; later it was linked to the rest of the facility through the addition of side benches and enlargement of the doorway. In this way, the original length of the hall—11.25 meters (its width was 4.20 meters)—reached 17.50 meters. The first layer of paintings was later replaced by another, and new stucco figures completed the decoration of the rear wall.

Statues of Cautes and Cautopates stood in the two niches at the entrance. Only the former is preserved. It was probably in origin a statue of Mercury transformed by the addition of stucco. The niche in the rear wall, recently restored, is unique in Rome. In addition to the usual image of Mithras killing the bull (the nude representation of the god, however, is exceptional), the niche contains a representation of the god Saturn lying down; his body is made out of amphorae covered with stucco. In a large graffito on the left side of the niche, a follower proclaims his birth into the light—that is, his rebirth, thanks to the initiation—on 21 November AD 202. The Mithraeum was thus already in existence in that year.

The most important feature of the sanctuary is the paintings that decorate the side walls above the benches; a break in the middle of the right wall that originally contained a door was later closed and transformed into a throne. There are two superimposed registers that, however, represented analogous subjects.

On the right wall, from left to right, the paintings depict the following:

1. A seated man wearing a Phrygian cap and dressed in red. To the left of his head is the inscription nama (patribus) / ab oriente / ad occidente(m) / tutela Saturni.

2. A young man with a halo and holding a globe in his hand. The inscription reads (na)mai tute(l)a S(ol)is. The inscription of the lower level, visible higher up where the plaster fell off, is nama h(el)iodrom(i)s / t(utela . . . ).

3. The legs and right arm of a figure, above which runs the inscription (na)ma persis / tutela (Mer)curis [sic].

4. Another person whose image is less easily distinguishable. Above the head is the inscription nama l(e)on(i)b(us) / tutela Iovis.

5. A person, in a three-quarter pose, who holds the cloak of the preceding figure and carries a roundish object with the other hand, clasped against his chest. The inscription reads nama militibus / tutela Mart(is).

6. A person standing and holding a deep red object in his hand. Above the head is written nama nym(phis) / tut(ela Ve)n(eri)s.

7. Only traces of this figure are visible.

The meaning of this procession and of the strange names is best explained through a letter of St. Jerome written in AD 403:

Did not your relative Gracchus . . . a few years ago when he was the city prefect [in 377] overturn, smash, and burn a Mithraic grotto and all those monstrous images by which they are initiated, such as the Crow (corax), the Bridegroom (nymphus), the Soldier (miles), the Lion (leo), the Persian (perses), theRunner of the Sun (heliodromus), the Father (pater), and, after sending them forth like hostages, did he not obtain the baptism of Christ?

This is a case of a destruction of a Mithraeum by Christians, during approximately the same years that the Mithraeum at S. Prisca was destroyed. The interest of the passage from St. Jerome is the list of the grades involved in Mithraic initiation, which we find in the same sequence along the painted wall of theMithraeum. Thus, we can complete the inscription by adding the missing last figure: nama coracibus—tutela Lunae. A planet corresponds to each of the seven grades of initiation, which are listed in ascending order of importance (corax, nymphus, miles, leo, perses, heliodromus, pater). Nama is a Persian word that may signify honor or veneration. The phrase that is continuously repeated can thus be translated, for example, “honor to the lions, protected by Jupiter.” The presence of the planets in a cosmic cult is not surprising. The seven heavens are represented, for example, in the floor of the Mithraeum of the Seven Spheres at Ostia.

The six figures that follow on the same wall, beyond the door, are real persons, indicated by their names, all of whom hold the grade of leones. They are bringing a bull, a rooster, a ram, a crater, and a pig. A similar scene must have been represented in the preceding painting, as appears at some points where it is visible.

The procession of the leones continued on the left wall. A grotto with four persons is shown at the end of the cortège on the right. Two of these, Mithras (on the right) and the Sun (on the left), are reclining at a banquet, while the other two, one of whom has the head of a crow, are serving them. This is evidently a representation of the alliance between Mithras and the Sun. To the left of the main room are other rooms that must have been used for functions connected with the sanctuary, such as initiatory ceremonies.

THE THERMAE DECIANAE In AD 252, the emperor Decius commissioned a bath complex, which he named after himself: the Thermae Decianae (FIG. 90:6). The location of this complex is known and some remains from it still survive. Inscriptions found more or less in situ, one of which is preserved in the courtyard of the Casale Torlonia, allow us to reconstruct the history of the building in addition to confirming its location. We know of one restoration that was undertaken under Constantius and Constans and another in 414, after the sack of Alaric. Numerous works of art were discovered in the area of the baths, including the young Hercules in green basalt and the relief of the sleeping Endymion, both in the Capitoline Museums. The plan of the building is recorded in a sketch by Palladio, making it possible to reconstruct the surviving remains. The most noteworthy of these is an apse in the hall at the southern corner. The size of the complex’s central section was approximately 70 × 35 meters.

The baths were built on top of older buildings, partially preserved in the basement of the Casale Torlonia and underneath Piazza del Tempio di Diana. Several walls in opus quasi reticulatum contain First Style paintings, dating to the end of the second century BC—among the few known examples of this style in Rome. Several halls of a large building have been preserved up to their vaults, together with their mosaics and paintings (small objects, landscapes, masks, and flowers in panels). Brick stamps and the style of the wall paintings date the structure to the time of Trajan or Hadrian. The buildings may have eventually come into the possession of Decius, and were adapted by the emperor to construct his baths. In fact, we know that other members of his family resided on the Aventine. The possibility that this is the (Domus) Privata Traiani, which some identify as the building under S. Prisca, should not be ruled out. Decius’s assumption of Trajan’s name confirms the association he sought to foster between himself and his predecessor.

THE PLAIN OF THE EMPORIUM The ancient port of Rome, situated on the left bank of the Tiber in the bend that faced the Velabrum and Forum Boarium, had no room for expansion, as it was hemmed in between heavily built areas. After the Second Punic War, Rome experienced an intense growth in both population and in commerce. It then became necessary to find space for a new port complex that could meet the needs of the times. The most suitable place was the open plain south of the Aventine. Here the aediles of 193 BC, Lucius Aemilius Lepidus and Lucius Aemilius Paulus, built their new port (Emporium) and the Porticus Aemilia that stood behind it. Subsequently, the censors of 174 paved the Emporium in stone, subdivided it with barriers, and made stairways that descended to the Tiber; they were also responsible for completing the Porticus Aemilia (FIG. 90), of which important elements survive in the area south of Via Marmorata, between this street and Via Franklin. The Severan Marble Plan represents the porticus with remarkable precision.

This immense building made of tufa in opus incertum—one of the oldest examples of this technique—was 487 meters long and 60 wide. The interior was divided by 294 piers into a series of rooms, arranged seven rows deep, that formed fifty aisles, each 8.30 meters wide; these were roofed by a series of small vaults, one above the other, following the light slope of the terrain. Several walls are still visible on Via Branca, Via Rubattino, and Via Florio. The building, standing about 90 meters from the river, was closely connected to the port, evidently functioning as the depot for arriving merchandise. Little by little, this space was subsequently filled in with other constructions, especially during the reign of Trajan.

The Emporium was discovered in the years 1868–70 during work on the Tiber’s embankment and was reexplored in 1952; several sections, recently cleaned and restored, are still visible, embedded in the massive wall of Lungotevere Testaccio. The facility was a wharf, roughly 500 meters long and 90 meters deep, with steps and ramps that descended to the river (the dock at Aquileia provides a similar, better-preserved example). Large protruding travertine blocks with holes for mooring the ships were built into the front of the dock. The surviving structural elements, for the most part in opus mixtum, are Trajanic reconstructions.

Over time, the entire plain of Testaccio became filled with buildings, especially with food warehouses, as the needs of the city grew. With the increase in population at the end of the second century BC and the beginning of subsidized distributions of grain and other foodstuffs, instituted during the tribunate of Gaius Gracchus, new warehouses became necessary. In response to this need, the Horrea Sempronia, Galbana, Lolliana, Seiana, and Aniciana were built. The best known among these were the Horrea Galbana, called the Horrea Sulpicia during the Republic (FIG. 90:9). A part of this building is shown on the same fragments of the Severan Marble Plan on which the Porticus Aemilia appears; it stands behind the porticus, but with a different orientation. During construction of the Testaccio neighborhood, several of its walls reappeared. The building, constructed entirely of tufa in opus reticulatum, was laid out around three large rectangular courtyards surrounded by porticoes, onto which long rooms opened. It was recently demonstrated that this was only a part of the building, the one reserved for the lodging (ergastula) of the slaves, who were divided into three cohortes, one for each courtyard. The warehouse proper stood farther east, between the ergastula and Monte Testaccio, which was formed from the refuse of the nearby horrea.

The building was restored by the emperor Galba (AD 68–69), but its original construction can be precisely dated: in front of the horrea was the tomb of the consul Servius Sulpicius Galba, almost certainly the official of 108 BC who was responsible for the construction of the building. This would date the building to around 100 BC, during the era of the tribune Saturninus. The irregular opus reticulatum in which the warehouse was constructed is one of the oldest known examples of this technique.

MONTE TESTACCIO The artificial hill called Testaccio (that is, Mons Testaceus, “mountain of potsherds”) is about 54 meters above sea level (30 above the surrounding area), with a circumference of one kilometer and a surface area of about 20,000 square meters (FIG. 90). It is roughly triangular, occupying a portion of the corner that lies between the Aurelian Wall and the river, at the southern end of the city. The hill was created from the discarded amphoras that contained the products brought to Rome’s home port.

The wagons that climbed the hill to unload the amphoras originally ascended by way of a ramp that divided in two at the northeastern corner. The surface area of the dump, the only part that we know very well, consists almost exclusively of somewhat spherical oil amphoras—they are called Dressel 20—that came from Spain, bearing a trademark on one of the handles. The name of the exporter, the various inspections at departure and arrival, and the consular date were marked on the body of the vessels with a brush or a quill. Most of the amphoras are dated between 140 and the middle of the third century AD.

This extraordinary hill contains the entire economic history of the late Republic and Empire.

THE PYRAMID OF GAIUS CESTIUS The Pyramid of Gaius Cestius was incorporated within the Aurelian Wall, alongside Porta S. Paolo, and was known in the Middle Ages as the Meta Remi (FIG. 90:11). The pyramid, like the so-called Meta Romuli that was in the Vatican near the modern Via della Conciliazione, is a funerary monument, as we learn from the twice-repeated inscription, on the eastern side and on the western side, where the modern entrance is located: C(aius) Cestius L(uci) f(ilius) Epulo, Pob(lilia tribu), praetor, tribunus plebis, (septem)vir epulonum (Gaius Cestius Epulo, son of Lucius, of the Poblilia tribe, praetor, tribune of the plebs, septemvir in charge of sacred banquets). A second inscription in smaller letters on the eastern side states that the work was completed in fewer than 330 days in accordance with the provisions of Cestius’s will. Two inscriptions, engraved on bases (now housed in the Capitoline Museums) that must have held bronze statues of the tomb’s occupant, mention several of Cestius’s famous heirs. Among these were the consul of 31 BC, M. Valerius Messalla, Lucius Cestius, the brother of the deceased, and M. Agrippa, Augustus’s son-in-law. The statues were erected with the money earned from the sale of Pergamene tapestries (attalica), which could not be placed in the tomb because of a law prohibiting extravagant display. This fact allows us to date the pyramid after 18 BC, the year of the law’s enactment, while mention of Agrippa precludes dating the monument any later than 12 BC, the year of the latter’s death.

Gaius Cestius is probably the praetor of 44 BC; his brother may have been praetor in 43 BC. It is not unlikely that one of the two was responsible for the construction of the earliest Pons Cestius, located between Tiber Island and Trastevere. Mention of the attalica, precious tapestries from Pergamon, and the extravagance of the tomb suggest that this Cestius might also be identified as a knight of the same name who resided in Asia Minor between 62 and 51 BC; he was probably a merchant or a tax contractor.

The pyramid measures 29.50 meters at the base and rises to a height of 36.40 meters (100 × 125 Roman feet). Four columns stood at its corners, two of which were reerected during the excavation of 1660 by order of Alexander VII, as a third inscription on the monument records. The structure was inspired by Egyptian models—Ptolemaic rather than pharaonic—that became fashionable in Rome after the conquest of Egypt in 30 BC; it resembles the Hellenistic pyramids of Meroe in Nubia. The foundations are in opus caementicium faced with travertine, while the superstructure, also in opus caementicium, was revetted in marble. On the western side a small door leads to the funerary chamber through a tunnel; this entrance is modern, however, opened in the seventeenth century. The chamber, preserved in the concrete core, is rectangular (5.85 × 4 meters) with a barrel vault. The brick revetment is among the oldest datable examples of the use of opus latericium in Rome. The rich decoration in the Third Style (the oldest datable example of the style), featuring panels with candelabra that frame two women standing and two seated, has for the most part disappeared. In the corners of the ceiling, four Victories with crowns drew attention to the center of the vault, which has now collapsed; a painting here probably depicted the apotheosis of C. Cestius. During the third century AD, the pyramid was incorporated in the Aurelian Wall.

An ancient road, Via Ostiensis, is visible nearby; it left the city through a gate of the Aurelian Wall that was later closed, probably by Maxentius. Alongside the street are the remains of buildings, probably horrea, and some cippi with dedicatory inscriptions to Silvanus and Hercules, which were discovered in 1930. In 1936, the remains of a bathing complex with mosaics were found on the outside of the walls; these can be dated to the first half of the second century AD.

ITINERARY 2

Trastevere

TIBER ISLAND According to an ancient legend, the island in the Tiber was formed from a harvest of grain gathered in the Campus Martius that belonged to the Tarquins and was thrown into the river after they were driven out. The island, however, is not that recent. Soundings of the island’s core undertaken during the large-scale reconfiguration of the Tiber at the end of the nineteenth century reveal that it consists of volcanic rock, similar to that of the nearby Capitoline, which was built up over the years by alluvial deposits. We do not know when the island was first occupied. The oldest cult is possibly that of the river god Tiberinus. A shrine on the island was dedicated to this divinity, together with Gaia, at least during the reign of Sulla.

The first important building that was to determine future activity on the island was the Temple of Aesculapius (FIG. 91:1). In 293 BC, the city was struck by a devastating plague. The Sibylline Books were consulted (between 292 and 291 BC) and it was decided that an embassy should be sent to Epidaurus in Greece, home of the cult of Aesculapius, the god of medicine. The Roman trireme sent to Epidaurus returned with a sacred snake, symbol of the god. The serpent swam from the Navalia, the military port situated along the bank of the Campus Martius, to the island, where it disappeared, thus indicating the place where the new temple should be built.

Construction began immediately afterward, and the shrine was inaugurated in 289. Its location coincides with the Church of S. Bartolomeo. The medieval well that survives near the church’s altar might correspond to the ancient sanctuary’s sacred fountain. Varro (L 7.57) reports that a painting with a military subject—knights who bore the archaic title Ferentarii—dated to the temple’s first phase; the work disappeared during the reconstruction of the building toward the middle of the first century BC. The porticoes in the sanctuary, as in Epidaurus, functioned as a hospital, as attested by the surviving inscriptions recording miraculous cures, votive offerings, and dedications to the divinity. The oldest dedications, found in the Tiber, date to the period just after the temple’s construction. Use of the island as an infirmary can be easily explained by its isolation from the rest of the city, a function that continued during the Middle Ages. Even today, the Ospedale dei Fatebenefratelli, founded in 1548, maintains the island’s age-old function. A dedication to Jupiter Dolichenus, offered by an official of the Ravennates, sailors of the fleet stationed in Trastevere, attests to the assimilation between this Asiatic divinity and Aesculapius.

Other minor sanctuaries occupied the northern side of the island. Shrines dedicated to Faunus and Veiovis in 194 BC probably stood near each other. A sanctuary to Iuppiter Iurarius, “guarantor of oaths,” stood on the site of the chapel of S. Giovanni Calibita, near the Pons Fabricius, where a mosaic with the name of the divinity was discovered. The name, unique to this cult, is a Latin alternative for “Semo Sancus Dius Fidius,” who thus effectively had a sanctuary on Tiber Island. The remains that were recently discovered in the hospital’s eastern sector probably belong to this shrine. An inscription also records the existence of a cult dedicated to Bellona, called Insulensis.

There must have been only one vicus on the island, whose name—Vicus Censorii—survives in several inscriptions. This is probably also the name of the street that connected the two bridges, the Pons Fabricius and Pons Cestius, by which the Campus Martius was connected with Trastevere. The present configuration does not differ significantly from the ancient. The small obelisk, two fragments of which are now in the Museo Nazionale di Napoli and a third in Munich, may have stood where the monument erected by Pius IX now stands.

The Pons Fabricius, called Ponte dei Quattro Capi (Bridge of the Four Heads) in Italian, links the island to the bank of the Campus Martius near the Theater of Marcellus. We know the precise date of its construction—62 BC: that is, the year after Cicero’s celebrated consulship—from Dio Cassius (37.45). On the other hand, we do not know whether it replaced another bridge or a ferry. The bridge is 62 meters long and 5.50 meters wide. The core of the structure consists of tufa and peperino ashlars, while the revetment, only partially preserved, is travertine. The brick facing dates to 1679, as attested by the inscription of Innocent XI still preserved at the bridgehead facing the island. The two large arches, slightly depressed, have a span of roughly 24.50 meters, resting on a central pier pierced by a small arch to reduce the force of the water against the structure during flooding. Even the parapets, which disappeared during the construction of the embankment wall at the end of the nineteenth century, were punctuated by two similar arches. Two quadrifrons herms were inserted in the modern balustrade at the beginning of the bridge facing the Campus Martius. The grooves in the statues may have supported the original bronze balustrades.

An inscription in large letters, repeated four times above the two large arches on both the upstream and downstream sides, records the name of the builder, Lucius Fabricius, son of Gaius, curator of roads (Curator Viarum). The style of the construction and the inscription accord with the date of 62 BC reported by Dio Cassius. A later inscription in smaller letters appears twice on the arch closest to the Campus Martius, bearing the names of Marcus Lollius and Quintus Lepidus, the consuls of 21 BC. Evidently, the inscription records a restoration that was probably undertaken after the great flood of 23 BC; on that occasion the Pons Sublicius was destroyed, and the Pons Fabricius must have suffered damage as well.

The other bridge of the island, connecting it with Trastevere, is the Pons Cestius, which was partially demolished between 1888 and 1892. Like the Pons Fabricius, it was probably built in the first century BC. Two praetors of this name, who were in office in 44 and 43 BC, come to mind. The praetor of 44 may be the individual buried in the pyramid of C. Cestius. If one of these officials was the builder, then the earliest phase of this bridge would date to around the middle of the first century BC. The last reconstruction was completed in AD 370 under the emperors Valentinian, Valens, and Gratian, as attested by an inscription in the bridge’s right parapet; a second identical inscription was thrown into the river by those defending the Roman Republic in 1849 during their unsuccessful attempt to cut the bridge off. There is some speculation that the medieval name of the island, Lycaonia, derived from a statue on the bridge representing this region of Asia Minor, which became a province in AD 373.

On the eastern tip of the island, a segment of a prow, carved in travertine, can still be seen; the sculpture alludes to the shape of the island, which resembles a ship. The island’s other end might have been distinguished at one time by the complementary image of a stern, but the hypothesis that the island was entirely transformed into a ship of stone should be dismissed. The prow has a core of peperino with a travertine facing; its formis that of a trireme, the warship that brought the snake of Aesculapius to Rome. The serpent is shown entwined around a staff in Aesculapius’s hand; the bust of the god, though seriously damaged, is still easily recognizable. A bull’s head may have served as a bollard for mooring cables. The construction almost certainly dates to the first half of the first century BC and is thus contemporary with the bridges; an inscription in fact attests to an extensive reconfiguration of the island at mid-century.

TRASTEVERE Very little remains visible of what was the most populous neighborhood in Rome during the late Empire (FIG. 91). Nonetheless, we can still discern the routes of several ancient streets that were partially preserved by their continuous use during the Middle Ages. One of the temples in the area, that of Fors Fortuna at the first milestone of Via Portuensis, may be represented on the Severan Marble Plan as the circular building just beyond the present-day Porta Portese; the traditional view that the remains found in 1860, in what was then the Vigna Bonelli, constitute this temple should be rejected. A sanctuary of Hercules Cubans was discovered in 1889 along Viale Trastevere, halfway between Piazza Nievo and the Trastevere Railway Station, containing, among other things, busts of charioteers. The sanctuary of Fons must have been in the place now occupied by the Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione. In 1914, during the excavation of the ministry’s foundations, an inscription was discovered with a dedication to Fons offered by two freedmen and dated 24 May AD 70. The legendary tomb of King Numa was located near this sanctuary. The position of the sanctuary of Furrina along the hillside below Villa Sciarra has also been ascertained on the basis of an inscription.

No trace remains of the largest public complex in Trastevere, the Naumachia built by Augustus in 2 BC near the Horti of Caesar. The inauguration of the Temple of Mars Ultor was celebrated here with naval battles; the Aqua Alsietina, stretching almost 33 kilometers from Lake Martignano and Lake Bracciano, provided the water. The discovery of a section of the aqueduct allows us to locate the site near S. Cosimato and is confirmed by a fragment of the Severan Marble Plan relating to this area; it reveals an open space of dimensions analogous to those recorded in the Monumentum Ancyranum: 536 meters long by 357 meters wide.

The ruins of ancient Trastevere that can still be seen lie mostly along the first stretch of Via Aurelia, the modern Via della Lungaretta. Important ancient buildings are visible under the Church of S. Cecilia, uncovered for the most part in 1899 and further in recent excavations (FIG. 91:2). The building under the central nave on the east is the oldest. There remain a tufa wall in opus quadratum and several columns and piers, also of tufa. The features of the structure call to mind a utilitarian building (horrea) of the Republican era. Remains of another structure, probably a private house, lie under the front porticus of the church; here too are indications of a Republican date, including a wall in opus reticulatum and a floor in opus signinum with a triple meander in white stone tesserae. The ruins attest to reconstructions undertaken during the Empire—from the second to the fourth century.

The transformation of the tufa building can be dated to the period of the Antonines. The change involved the insertion of a room with seven hemispherical tanks made of brick, which gave rise to the notion that this was a tannery; it has been hypothetically identified as the Coriaria Septimiana recorded in the Regionary Catalogues. In a nearby room there is a kind of lararium, a niche with a tufa relief representing Minerva in front of an altar. The sides of the niche are revetted with two terracotta reliefs of the so-called Campana type that come from the same mold, depicting a Dionysian scene. A Christian titulus was later installed in these buildings, while the basilica itself was built by Paschal I at the beginning of the ninth century.

On the corner of Via di Montefiore and Via della VII Coorte, near Viale Trastevere, there is an Imperial building that is of considerable importance for the topography and history of Region XIV: the Excubitorium of the Seventh Cohort of the Vigiles (FIGS. 91:4; 93). The discovery took place in 1865–66, but the excavations were completed only later. The building was a private house that had been converted into a barracks toward the end of the second century AD. It can be identified with certainty as the main headquarters of Cohort VII, which oversaw Regions IX (or XI) and XIV, and not as one of the smaller posts, as is generally held. The building, whose floor is 8 meters below modern ground level, consists of a large hall that was paved with black-and-white mosaics, which disappeared during World War II. At the center is the basin of a hexagonal fountain with concave sides; it lies on axis with a rectangular exedra containing an arched entrance that is framed by two Corinthian pilasters surmounted by a pediment; the construction is entirely of brick. Some of the original frescoes within are still preserved. A graffito reveals the function of the room: it was the chapel of the barracks, a kind of lararium dedicated to the Genius of the Excubitorium. Other rooms open onto this central area all around, evidently the dormitories of the vigiles. One of these was a bath.

FIGURE 93. Excubitorium of the Seventh Cohort of the Vigiles.

Numerous graffiti were discovered on the walls of the large atrium. The words sebaciaria and milites sebaciarii, evidently connected with the word sebum (tallow), appear often. The terms must have pertained to the soldiers on guard duty and night patrol, for which they were equipped with tallow torches. Many of the graffiti can be dated to between AD 215 and 245.

The Excubitorium of Trastevere provides us with a precise idea of the organization and life of the vigiles, a unit that was founded by Augustus in 6 BC with duties similar to those of modern firemen and night police. We know that there were fourteen excubitoria in all, one for each region; seven of these were the official headquarters of the seven Cohortes Vigilum, of which the station in Trastevere was one. We also know the location of five of these barracks: those of Regions II, V, VII, XII, and XIV.

Several ancient buildings, datable between the beginning of the empire and the Severan era, were found on various occasions in the immediate vicinity of the Church of S. Crisogono on Viale Trastevere. None of these can be seen today, excluding the few remains that are still accessible in the basement of the church; the first Christian building was installed here in the eighth century.

Extensive excavations in the area of the Caserma Manara, located between the churches of S. Francesco a Ripa and S. Maria dell’Orto, have brought to light a series of large Imperial warehouses that face the river. An important fragment of a first-century AD marble plan, on the same scale as the Severan Forma Urbis, was found here and provides a view of the area around the Temple of the Dioscuri in the Circus Flaminius.

THE SYRIAN SANCTUARY OF THE JANICULUM A sanctuary dedicated to eastern divinities was discovered in 1906 on the southern slope of the Janiculum; the modern entrance is on Via G. Dandolo, no. 47 (FIGS. 91:7; 94). Of the three phases that were identified at that time, only the last one has left substantial remains that can still be seen. An inscription in Greek found on the site contains a dedication to Zeus Keraunios and to the Nymphae Furrinae. The sacred grove of Furrina was thus in the immediate vicinity, probably near Villa Sciarra, which rises above the site. It was here in 121 BC that Gaius Gracchus took his own life after his flight from the Aventine. Here was the source of a fountain sacred to the nymph Furrina, which was diverted into a channel below the temple. Later on, the ancient cult became associated with Syrian divinities.

The change must have occurred as early as the beginning of the first century AD, as several inscriptions indicate. Afterward, the temple was reconstructed, probably by Marcus Antonius Gaionas, a Syrian (probably a wealthy merchant) who was a contemporary of Marcus Aurelius and Commodus, mentioned in a funerary inscription, among other notices. The sanctuary was destroyed, possibly in a fire, and much material from the earlier structure was reused in the building that survives, whose date, a topic of debate, has been assigned to the fourth century AD.

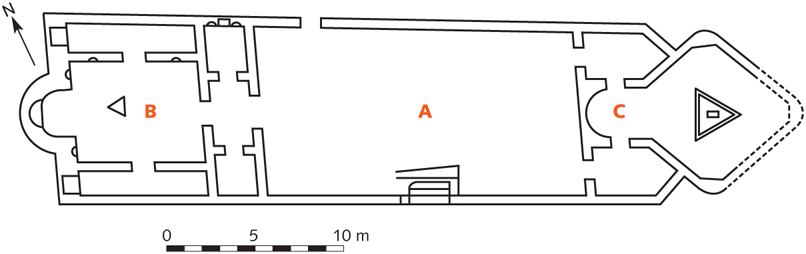

The sanctuary, an elongated structure built mostly of small parallelepipedal blocks of stone, consists of three distinct parts: a rectangular court in the middle (A) that functions as the entrance (the main door was at the center of the southern side); a room with a curious floor plan incorporating a number of shapes (C); and a basilical structure on the west (B) that is preceded by a sort of atrium or narthex onto which two lateral cellas open. A single entrance leads into the central nave, which terminates in an apse that has a semicircular niche flanked by two smaller niches; a human skull was discovered below the central niche. The side aisles could be entered only from the central nave and terminated in rectangular niches. There are four other semicircular niches located along the sides of the doors in the walls that divide the central nave from the two aisles.

The main cult statue, located in the central niche, was discovered by the excavators. It is a seated Jupiter that is unfortunately missing its head and other features, but that resembles a Serapis. A triangular altar stands in the middle of the central nave.

FIGURE 94. Plan of the Syrian Sanctuary of the Janiculum.

The third part of the sanctuary, lying to the east, is the most unusual. It was approached from the courtyard through two doors (one of which was blocked off at a later time), leading to two small rooms. Side doors in these antechambers led to an octagonal hall with an apse on the western end. Several sculptures were found here: an Egyptian statue in black basalt (in the apse), a statue of Bacchus with gilded face and hands, and other statues, all predating and reused during the temple’s last phase. The most interesting discovery was made within a hollow space underneath the triangular altar at the center of the octagonal hall: several eggs and a bronze statue of a man caught in the coils of a serpent. The significance of the statuette, which is to be identified as Osiris, seems clear: Osiris (possibly also the subject of the Egyptian statue), god of nature, dies and is reborn every year. The burial of the god and his rebirth through the seven celestial spheres, symbolized by the seven coils of the serpent, allude, like the eggs, to the allegorical death and rebirth of the neophyte before and after initiation to the cult. The ceremony apparently took place in this secluded room.

The likely date of the sanctuary—mid-fourth century AD—and its syncretic character identify it as one of those cult sites typical of late paganism, before its final extinction after the battle of Frigidus; the most important example of cults of this sort is the Phrygianum in the Vatican.

ITINERARY 3

The Vatican

THE CIRCUS OF CALIGULA, THE VATICAN NECROPOLIS, AND THE BASILICA OF ST. PETER The Vatican hills and the plain enclosed between them and the Tiber—the ager Vaticanus—never constituted a formal part of the city, but were a suburban area, crossed by streets lined with tombs and villas, the most important of which came into the Imperial holdings at an early date (FIG. 92). The Circus of Caligula, the most important building in the area in addition to Trajan’s Naumachia and Hadrian’s Mausoleum, was probably a private circus, part of the Villa of Agrippina and thus similar to the Circus of Maxentius.

An important group of monuments was discovered during construction of the river embankment at the end of the nineteenth century. They lie outside Porta Settimiana, on the road along the Tiber that linked Trastevere with the Vatican, and include the so-called tomb of the Platorini, the Cellae Vinariae Nova et Arruntiana, and the Villa della Farnesina (FIG. 91:8–10). Identification of the latter as the Villa of Agrippa is confirmed by the proximity of the Horti of Agrippina, Agrippa’s daughter, and of the Pons Agrippae, corresponding to Ponte Sisto.

The remains discovered in 1959 under the Ospedale di Santo Spirito may belong to the Villa of Agrippina. Three structures can be distinguished: one farther to the west with walls in opus reticulatum and courses of brick; one in the middle that reveals two phases (the first in opus reticulatum, the second in opus reticulatum and brick); and another farther to the east, in opus latericium, distinguished by the inclusion of a large exedra. The oldest phase of these buildings dates to the beginning of the first century BC, as the structures and polychrome mosaic floor show. A large marble basin with sea scenes, dated around 100 BC, comes from here; it was discovered a few decades ago and was moved to the Palazzo Massimo.

The position of the Circus of Caligula, on the left side of St. Peter’s Basilica, is secure. Its northern side corresponds to the left aisle of the church and was bordered by the row of tombs of the Vatican necropolis. Even the position of the obelisk is certain, as it remained in its original position until 1586, when it was moved to the center of the modern Piazza S. Pietro. The foundation of its base was discovered during an excavation near the side of the church, between it and the sacristy. Later, when the circus was no longer in use, a large mausoleum, dating to the reign of Caracalla and later transformed into the Rotonda di Sant’Andrea, was built near the obelisk.

The uninscribed obelisk is the second largest in Rome, after the one near S. Giovanni in Laterano. It measures 25 meters and was brought from Egypt on a boat of exceptional size, as we learn from Pliny the Elder (NH 16.76); Claudius later had the vessel sunk to serve as the foundation for a breakwater in his artificial port. Recent excavations have brought the remains to light and have confirmed Pliny’s report. Caligula’s dedication to Augustus and Tiberius is repeated on two sides of the obelisk’s base. Several holes from an earlier inscription reveal the name of C. Cornelius Gallus, prefect of Egypt under Augustus, who had the obelisk cut for a Forum Iulium that he built in Alexandria.

The size of the circus has recently been shown to be considerably larger than previously thought—that is, if a curved wall, discovered on Via del Santo Uffizio beyond Bernini’s colonnade, belonged to it. The discovery has led some to argue that the carceres were located here. The identification is uncertain, however. In any event, the fact that this wall contains no openings, together with its position east of the circus, suggests that is was associated with the curved end that lies opposite the carceres. The starting gates would thus have been located near the apse of the basilica. This configuration better suits the orientation of other circuses in Rome, whose carceres are on the western or northwestern sides.

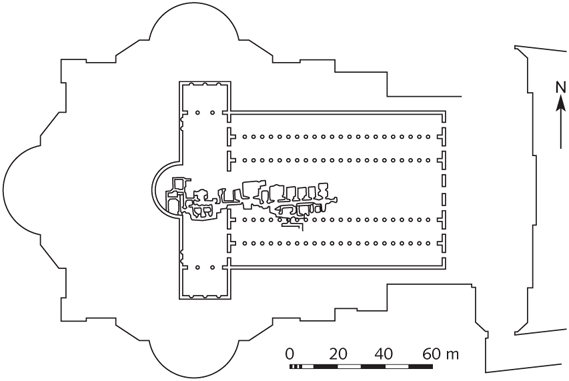

FIGURE 95. Plan of the Vatican necropolis.

An important necropolis was excavated under the basilica, consisting of brick mausolea that lined a street running along an east-west axis (FIGS. 92:3; 95, 96). The northern row of tombs is older, dating to the second century AD, as the preference for cremation burials indicates. A chronological development can easily be observed in the buildings as they progress from east to west. The tombs at the south are later, dating to the third century.

Mausoleum A, which was not excavated, has an important inscription on its facade that records a part of the will of the deceased, C. Popilius Heracla, according to which he asks that his tomb be built “on the Vatican, near the Circus alongside the tomb of Ulpius Narcissus.” This provides valuable topographical information regarding the location of the Circus of Caligula. Mausoleum B contains two rooms and rich architectural and painted decoration. An inscription mentions that a Fabia Redempta was buried here. Mausoleum C has an inscription on its facade that names its owner: L. Tullius Zethus; his two sons are named in funerary inscriptions within the mausoleum on the northern side. The tomb is richly decorated in stuccos and preserves its black-and-white mosaic floor. Many sarcophagi were thrown inside the mausoleum during the construction of the basilica. Mausoleum E was built by Tyrannus and Urbana, Imperial freedmen of Hadrian. Of particular note among the paintings is a pair of peacocks facing a basket of flowers and fruit. Mausoleum F belongs to two families of freedmen, the Tullii and the Caetennii. Mausoleum G also preserves its elegant decoration, one scene of which features a slave giving money to his master, who is seated alongside a table.

Mausoleum H is one of the largest and most remarkable structures in the Vatican necropolis. It belonged to the Valerii, as the inscription of a Valerius Herma that was affixed to the facade reveals. The stucco decoration was in origin partially gilded; herms, also made of stucco, line the walls. Several sarcophagi are preserved inside. Next to the central niche, which contains a representation of Apollo-Harpocrates, several Christian paintings and inscriptions were added at a later date. Among these is the following: Petrus roga Christus Iesus pro sanc(tis) hom(ini)b(us) chrestian(is) (ad) corpus tuum sepultis (Peter, pray to Jesus Christ on behalf of the holy Christians buried near your body).

Mausoleum I predates that of the Valerii. The central apses in the walls are framed by small stuccoed terracotta columns and also have lunettes dressed in stucco. The walls preserve remarkable paintings, among which are two that represent the myth of Alcestis. On the floor is a black-and-white mosaic portraying the rape of Proserpina, whose association with death is clear. Mausoleum L belonged to the Caetennii, as the inscription on the facade bearing the name of M. Caetennius Hymnius reveals. Here too the elegant decoration is preserved within.

Mausoleum M is among the most important in the necropolis. The tomb, which had already been seen in the sixteenth century, belonged to the Julii and should be dated to the Severan age. Figures that are clearly Christian can be found within: Jonah in the jaws of the whale, a fisherman, the Good Shepherd. An important mosaic on the vault depicts Christ on the chariot of the Sun, like Apollo. Mausoleum N is still largely buried. The inscription on the facade names the owners of the tomb: M. Aebutius Charito and L. Volusius Successus. Mausoleum O belonged to the freedman T. Matuccius Pallas, as we learn from the inscription on the outside. In front of Mausoleum O are Mausoleum T, which belongs to Trebellena Flaccilla and is richly decorated with stuccos and paintings, and Mausoleum U, which is similar in all respects to the previous tomb. Other mausolea, also dated to the second and third centuries, were discovered farther to the west under the Church of S. Stefano degli Abissini and follow the same alignment as the others.

Later on, other tombs filled all the available space, but there were few traces of Christian burials, which were instead concentrated to the west of the mausolea. Here there was a small rectangular space (P), roughly 7 × 4 meters, that was closed on three sides and only half closed on the east. The area is almost completely surrounded by mausolea that were built from the first to the fourth century around what has been identified as the tomb of Peter. This was originally a simple grave, over which a monument was erected around the middle of the second century, at the same time as the surrounding mausolea. The monument rested against a wall in the rear and was accessible from the south by two stairways.

The monument, inproperly called the Trophy of Gaius, consisted of a niche crowned by a slab of travertine that was supported in front by two columns; another smaller niche was inserted above. Its curvature was irregular, being deeper on the right, but perfectly symmetrical to an underground niche that held the tomb of the apostle. A graffito on the rear wall, next to the largest niche, confirms the identity of the monument; it bears the name of Peter in Greek letters.

FIGURE 96. The Vatican necropolis and the successive basilicas of St. Peter.

The tomb must have always been an object of veneration and particular concern among the faithful. In fact, although it had suffered damage in the third century (explained by some as the result of the need to move the remains of the saint ad catacumbas in 258), walls were subsequently added on the sides, and the floor and the largest niche were revetted in marble; the square in front of the monument was decorated with mosaics.

The basilica was built during the fourth century in such a way that the monument stood at the center of the presbytery, visible to the faithful (FIG. 96). The choice of the site on which to build the basilica in honor of the saint—the slope of a hill—is thus linked to the location of the tomb and required a solution to various and difficult problems. On the north, it was necessary to cut away a section of the hill, while on the south, a huge terrace wall was needed for filling in the difference in levels, which was as high as 8 meters. Some of the buildings that were considered dispensable had to be sacrificed, however, such as the two wings of the “red wall” against which the monument rested and even the upper part of the monument itself. Constantine’s basilica measured 85 × 64 meters and had five aisles, each separated by twenty-two columns. The colonnaded atrium was impressive.

The apse was on the western end at the center of a narrow transept that was clearly separated from the rest of the basilica by means of a foundation wall. The transept communicated with the side aisles through two three-mullioned openings accented by two columns. The rows of columns stopped in front of the transept, while the exterior walls that ran along the side aisles continued around the transept, forming two symmetrical open spaces at either end. The central part of the transept was also left open and contained St. Peter’s funerary monument, whose base sat 36 centimeters under the floor of the presbytery.

The tomb was isolated at the center of the presbytery within a base of pavonazzetto, on which a kind of aedicula, clad in the same marble and in porphyry, was erected. Above this stood a baldacchino supported by four spiral columns of Parian marble with representations of putti harvesting grapes (pergula). Two other similar columns stood behind and to the side, at the beginning of the curve of the apse. One of Constantine’s sons commissioned the decoration of the upper part of the apse with a mosaic, as can be inferred from an inscription; its subject is ambiguous. It may represent the entrusting of the law to Peter, or Christ among the apostles. An altar was not built, since the Constantinian basilica was designed as a funerary monument.

During the sixth century, the need to accommodate regular liturgical services and to protect the relics led to the raising of the presbytery floor and to the installation of a double row of six spiral columns, the inner row of which was closed by plutei. The tomb was approached by two lateral stairways that led directly to the monument along a semicircular corridor. Eleven of the twelve spiral columns were incorporated in the construction of the modern basilica: one, the “holy column,” was in the Chapel of the Pietà until fairly recently; two are in the Chapel of the Most Blessed Sacrament; and eight are in the balconies of the relics in the piers that support the dome, where Bernini wanted them. The basilica remained largely intact until, in the fifteenth century, Pope Nicolas V ordered its reconstruction, because at that time the fourth-century building was no longer stable.

Remains of a Roman street, sometimes identified as Via Triumphalis, were discovered inside Vatican City, north of Piazza S. Pietro along Via del Pellegrino. A variety of tombs lined the street, and their remains were discovered near the Fontana della Galera, under the Annona Vaticana, and above all under the autoparco built after 1956 (FIG. 92:4). During excavation for the foundations of this building, a burial site covering an area of roughly 240 square meters was found; it contained tombs for both cremation and inhumation burials and was in use between the Augustan period and the fifth century AD.

The Meta Romuli is another of the various tombs in the Ager Vaticanus, regarding which there is literary testimony. It was in the form of a pyramid, similar to that of Gaius Cestius, and remained standing until 1500, when Pope Alexander VI had it removed. In 1948, its foundations were discovered during the construction of the Casa del Pellegrino at the beginning of Via della Conciliazione. The Terebintus Neronis, a funerary monument consisting of two superimposed cylindrical elements, was preserved near the pyramid up to the fourteenth century (FIG. 92:1).

THE MAUSOLEUM OF HADRIAN Nerva was the last emperor buried in the Mausoleum of Augustus. As already noted, Trajan’s remains were interred in the base of his column. Hadrian began work on a new mausoleum that would become the dynastic tomb of the Antonines (FIG. 92:2). The site chosen for the monument was the Horti of Domitia in the Vatican. In order to link the tomb to the Campus Martius, a new bridge was built, the Pons Aelius, which was inaugurated in AD 134, as attested by the inscriptions at the two entrances, recorded in the Einsiedeln Itinerary; much of the structure still exists under the name Ponte Sant’Angelo. The bridge stood just upstream of the Pons Neronianus and consisted of three large central arches—the only features that survive—and two inclined ramps, supported by three small arches on the left bank and two on the right (FIG. 97). The ramps were discovered in 1892 during work on the river and then incorporated in the huge embankment.

The mausoleum rises on the right bank, immediately on the other side of the bridge. Because it was incorporated within the Castel Sant’Angelo during the Middle Ages, its structure remains largely intact (FIG. 98). We do not know when the work was begun, possibly around 130, but it was completed only in 139, after the death of Hadrian at Baiae; the emperor’s body was at first buried in Pozzuoli.

The building consists of a square base—89 meters on each side, 15 meters high—built in opus latericium, with vaulted radial rooms. At the center of this enclosure is the circular drum, 64 meters in diameter and 21 meters high, which the radial walls of the enclosure abut. For unknown reasons, the enclosure appears to have been built during a second phase, immediately afterward.

The exterior wall was revetted in marble, and marble tablets were affixed to it containing the epitaphs of those who were buried within the monument. Pilasters framed the enclosure, which was capped with a frieze of bucrania and garlands, fragments of which are preserved in the Castle Museum. Procopius (Goth 1.22) records that four bronze groups representing men and horses stood on each of the corners of the base. Outside the main structure there was another enclosure, a railing supported by piers, the peperino foundations of which have been excavated. Peacocks cast in gilded bronze probably stood on some of these piers; they are now in the Cortile della Pigna in the Vatican.

The original entrance with three bays does not survive. The drum of the tomb that forms the lower part of the Castello can best be viewed from the modern entrance, which is 3 meters higher than the ancient one. It is built in opus caementicium and dressed with peperino tufa and travertine. The exterior facing was marble.

A short corridor leads to the square vestibule, which has a semicircular niche in the rear wall (FIG. 98). This was probably where a large statue of Hadrian stood, the head of which is now displayed in the Sala Rotonda of the Vatican Museums. The original location of the large portrait of Antoninus Pius, the head of which is in the Castle Museum, is not known. The atrium was revetted in giallo antico marble (the clamp holes are still visible). The winding gallery that leads to the funerary chamber begins on the right. This corridor was built in opus latericium and had a marble wainscoting to a height of 3 meters, where it ended in a cornice. The vault is of rubble masonry, and the floor, several sections of which are preserved, is white mosaic. Four vertical light wells illuminate the passageway, which makes a complete circle and reaches a level 10 meters above the vestibule. From here, an axial corridor leads to the funerary chamber, located at the monument’s center.

FIGURE 97. Reconstruction of the Mausoleum of Hadrian along the Tiber.

The chamber is square (8 × 8 meters), with three arched rectangular niches, located on three of the sides and originally entirely revetted in marble. Two windows that open at an oblique angle in the vault illuminate the room. The funerary urns of Hadrian, Sabina, and Aelius Caesar were placed here. All the Antonine emperors and the Severans up to Caracalla were buried in the same place.