WESTERN ENVIRONS

Viae Aurelia, Campana, Ostiensis

HISTORICAL NOTES

The region west and southwest of Rome was shaped by the final stretch of the Tiber and was always crucial to the city’s commerce because of its connection with the area around the port. The region was economically important, since the survival of Rome depended rather early in its development on provisions arriving by sea. With the exception of Via Aurelia—probably founded by C. Aurelius Cotta, the consul of 241 BC—which connected Rome with maritime Etruria and later with Liguria and Provence, all the other roads that run southwest were intended to connect the city with the sea. The oldest is certainly Via Campana, so called after the Campus Saliniensis, the salt beds along the sea, which were connected by this road with the Forum Boarium and the salt warehouse close to Porta Trigemina. Via Campana followed the meandering valley of the Tiber in all its twists and turns. After Claudius built Portus, it was transformed into a transport road over which animal teams dragged barges loaded with goods from the port to Rome. Before that, when Rome’s major port was Ostia, the transport road must have followed the left bank. Two roads whose courses were shorter and straighter connected Rome directly with Ostia and Portus: Via Ostiensis (on the left bank of the Tiber) and Via Portuensis, both of which began at the gates of the Aurelian Wall bearing the names of their respective roads.

Two other early roads proceeded in a southerly direction: Via Laurentina and Via Ardeatina, which connected Rome with two very ancient Latin settlements along the sea, Lanuvium-Laurentum (the mother city of ancient Latium) and Ardea.

ITINERARY

Via Aurelia

Via Aurelia Vetus begins at Porta S. Pancrazio. As often happened, the name of this gate, which derives from the nearby tomb of the martyr, replaced the ancient one, Porta Aurelia, during the Middle Ages. A little farther on, near the entrance to the Villa Doria Pamphilj, lies the intersection where Via Aurelia (now Via Aurelia Antica) veers toward the right, while on the left another street (the present-day Via di S. Pancrazio, which becomes Via Vitellia) follows an ancient course, probably called Via Vitellia in ancient times as well. The second road leads to Piazza S. Pancrazio, where the entrance to the basilica and catacombs, named for the saint, are located.

According to tradition, Pancratius was martyred under Diocletian on 12 May 304. He was buried in a cemetery that was already in existence during the late Republic, around which the galleries of a Christian catacomb subsequently multiplied. Pope Symmachus (498–514) erected a small basilica over Pancratius’s tomb, of which no trace remains. The present basilica is the work of Honorius I (625–38), with substantial renovations dating to the twelfth and seventeenth centuries. Entry to the catacomb is from the church. The galleries, parts of which have not yet been fully explored, are divided into three regions; none date back prior to the fourth century.

To visit the ancient remains inside the Villa Doria Pamphilj it is necessary to turn back and enter the public park of the villa through the gate at Piazza di S. Pancrazio.

The most interesting columbaria still visible are behind Casino del Belrespiro. The “colombario maggiore,” discovered in 1821, is half underground and contained more than five hundred burials. This columbarium is particularly remarkable for its paintings, now detached and preserved in the Museo delle Terme. The “colombario minore,” with its four arcosolia and its rich painted stucco, was discovered in 1838. This site, possibly Hadrianic, clearly postdates the “maggiore.”

Nearby, just east of here, there is a burial enclosure made of tufa ashlars, with a false door at the center of the front side.

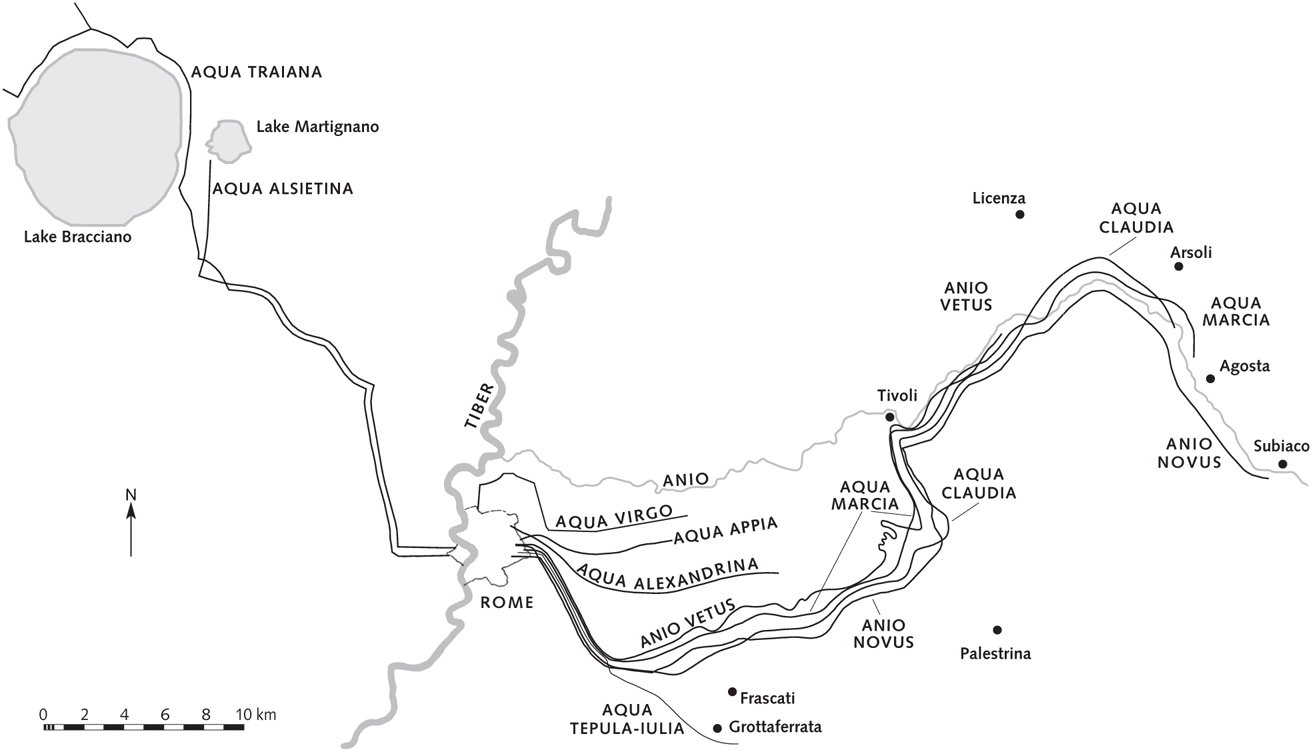

Along the right side of Via Aurelia the remains of the Aqua Traiana come into view almost immediately beyond the park of the Villa Doria Pamphilj; the aqueduct carried water from Lago di Bracciano all the way to Trastevere. Later, part of the structure was reused for the Acqua Paola, brought to Rome by Pope Paul V (1605–21). The showpiece of this aqueduct is the monumental fountain on the Janiculum. Farther ahead, the road is spanned by the large papal arch over which the aqueduct passes, known as the Arco di Tiradiavoli.

Via Campana

Between the fifth and sixth milestones of Via Campana stood the very ancient sanctuary of the Dea Dia, whose cult was in the care of the Fratres Arvales, created, according to tradition, by Romulus himself. As has long been known, the sanctuary was at the early border of Roman territory, the Ager Romanus Antiquus. A second temple of Fors Fortuna in this area, which we know was situated at the sixth milestone of Via Campana, must have stood near that of the Dea Dia.

Although we know very little about the earliest worship of the Dea Dia, we do know a fair amount about the nature of the cult as it was renewed by Augustus. A large number of fragments from inscriptions have come down to us, recording the proceedings of the ceremonies during the period between the reigns of Augustus and of Gordianus.

The sanctuary spanned both sides of the present Via della Magliana, between Colle delle Piche and the Tiber. Chance discoveries occurred during the sixteenth century, and an excavation was carried out in 1857. At that time a plan of the buildings that were still visible was made, part of which is quite fanciful. The French Archaeological School has been conducting regular excavations of the site since 1975 that are beginning to clarify the sanctuary’s complicated topography. Several of the main buildings mentioned in the inscriptions (the Temple of the Dea Dia, the Caesareum, the tetrastylum, the circus, and the baths) have been identified. The temple, part of which is still visible in a basement along Via della Magliana, was a large rotunda situated at the northern edge of the area. At the other end of the sanctuary, near the Tiber, remains of the baths have come to light. The work undertaken to date has shown that the complex was completely rebuilt under Alexander Severus and that its various buildings were brought together within a large porticus, closed on the north by the temple and on the south by the baths. The original sacred grove (Lucus Deae Diae), then, was set within a monumental enclosure.

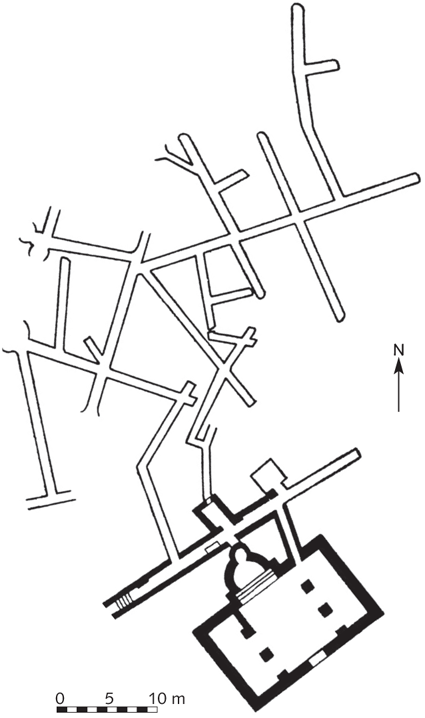

The Catacombs of Generosa, which occupy Monte delle Piche directly above the sanctuary of the Dea Dia, were begun and developed entirely during the course of the fourth century AD (FIG. 127). The cemetery was originally intended for the burial of a group of martyrs during the persecution of Diocletian, including Simplicius, Faustinus, and Beatrice. We know nothing of Generosa, who was probably the owner of the property.

During the second half of the fourth century, a small apsidal basilica, perhaps the work of Pope Damasus, was erectednear the tombs of themartyrs. The grilled window above the cathedra, at the center of the apse, is especially interesting. EUR The EUR (Esposizione Universale Roma) district is well worth visiting because of the important museums located there, including the Museo della Preistoria e Protostoria del Lazio (formerly the Museo Pigorini), the Museo della Civiltà Romana, and the Museo dell’Alto Medioevo.

FIGURE 127. Catacombs of Generosa. Plan. (After Testini)

The Museo della Preistoria e Protostoria del Lazio collects the materials from the region that were formerly in the Museo Pigorini, with the addition of some of the finds in several very fruitful recent excavations, such as those at Osteria dell’Osa. The museum has been installed on the second floor of the Palazzo delle Scienze.

Via Ostiensis

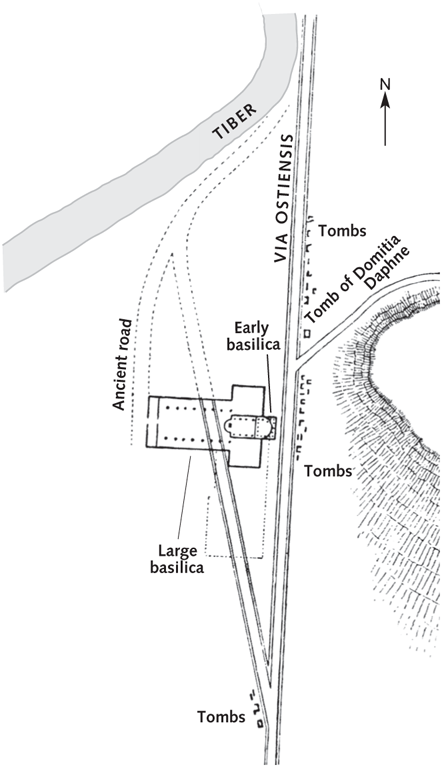

When Via Ostiensis reaches the Basilica of St. Paul, the road encounters a bottleneck between the Tiber and the Roccia di S. Paolo (FIG. 128). This whole area has the character of a huge necropolis, which was occupied from the Republican period to the end of antiquity. It is of special historical importance because it was the site of the tomb of the Apostle Paul.

FIGURE 128. Area around the Basilica of St. Paul. (After Marucchi)

In addition to the cluster of tombs north of the church, which are under a protective roof, remains of other burials can be seen beside the rock behind the basilica’s apse. Paintings now in the Museo della Via Ostiense at Porta S. Paolo come from one of these burial sites, which consisted of a room with three arcosolia.

No traces of the apostle’s tomb have been found, but only some remains of the “trophy” (resembling that of the grave of St. Peter) built above it by the presbyter Gaius around 200. After this, at the urging of Pope Sylvester (314–35), Constantine erected a small basilica within the narrow space available between Via Ostiensis and the iter vetus.

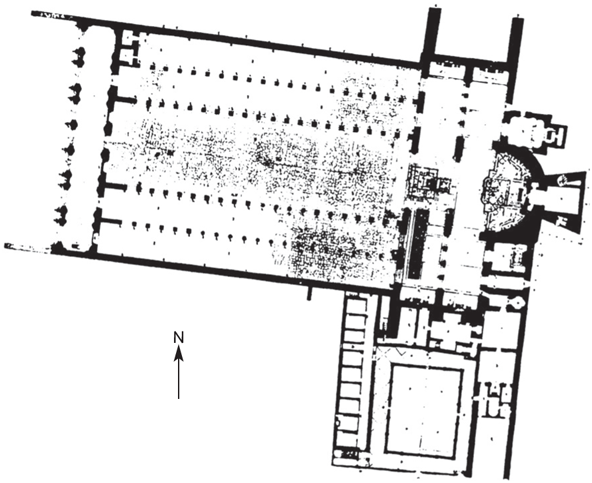

The large basilica was begun under Valentinianus II, Theodosius I, and Arcadius in 384 and completed under Honorius around 403, as attested by an inscription on the triumphal arch, although the inscription itself belongs to the restoration by Pope Leo I and Galla Placidia that took place after a fire around the middle of the fifth century. The Theodosian basilica is of a character quite similar to the Basilica of St. Peter and had equivalent dimensions (128 meters long and about 65 meters wide), with five aisles and a transept but without the rectangular exedras at the end of the short sides. The building remained substantially intact until 1823, when it was half destroyed by a fire (FIG. 129). The basilica was reconstructed between 1825 and 1854 in a style that provoked much controversy, and major work on the project continued until 1890; the quadriporticus was finished only in 1928.

FIGURE 129. The Basilica of St. Paul before the fire of 1823.

In the course of widening Via Ostiensis north of the basilica in 1919, a large portion of a necropolis was found, one section of which is displayed under a protective canopy. It is a fascinating complex, which developed over five centuries, beginning in the second century BC and continuing to the fourth century AD, expanding from west to east; i.e., from Via Ostiensis toward the Roccia di S. Paolo. At a number of points one can see several strata of tombs, built on top of one another. The necropolis clearly documents the progressive change from the rite of cremation to that of inhumation during the course of the second and third centuries AD. From a historical perspective, this evidence makes the cemetery one of the most interesting in Rome.

FIGURE 130. The Roman aqueducts.