When, where, and how have women exercised supreme political authority most successfully? This small book introduces a large subject, emphasizing a distinctive aspect of Western history which to the best of my knowledge has never been examined systematically: Europe's increasing accommodation to government by female sovereigns from the late Middle Ages to the French Revolution. In order to place this development within the broadest possible context, the chronological core of the book follows a global survey of reliably documented female sovereigns before uncontested women monarchs emerged in fourteenth-century Europe, and it concludes with a sketch of conditions after the modern liberal-democratic era eroded monarchical authority throughout most of Europe, so that women could still inherit thrones but no longer ruled. No woman headed any European government between the death of Catherine the Great in 1796 and the election of Margaret Thatcher as prime minister of Britain in 1979—and few do today.

Between 1300 and 1800 thirty women acquired official sovereign authority over major European states above the level of duchies. My book concentrates on women who possessed the right to govern Europe's highest-ranking states, including more than a dozen kingdoms, the Russian Empire, and the Low Countries, not only because they are the most important politically, but also because they constitute a group of female rulers that is both large enough to suggest meaningful changes over time yet small enough to be manageable. These women, arranged in chronological order by the dates on which they assumed effective sovereign power, include the following:

1. (1328) Jeanne II, sixteen years old and married, is invited to become monarch of Navarre; joint coronation with husband 1329; widowed 1343; dies 1349, succeeded by son.

2. (1343) Joanna I, nineteen, inherits Naples and Provence from grandfather; marries, but joint coronation canceled by husband's murder 1345; joint coronation with second husband 1352; widowed 1362; reigns alone despite two later marriages; deposed 1381; no surviving children; murdered 1382 by first of two adopted heirs.

3. (1377) Maria of Sicily, seventeen, succeeds father; kidnapped by Aragonese, married 1391 to teenage prince; joint coronation 1392; dies childless 1401, succeeded by husband.

4. (1382) Mary of Hungary, twelve, crowned king with mother as regent; deposed 1384, but usurper murdered 1385; mother also murdered 1385; fiancé crowned 1386; joint reign, dies childless 1395, succeeded by husband.

5. (1383) Beatriz of Portugal, ten, succeeds father; married but deposed 1385 by illegitimate half brother; no children; date of death (after 1420) unknown.

6. (1384) Jadwiga of Hungary, twelve, crowned in Poland and married to converted pagan Jagiello of Lithuania; joint reign until she dies 1399, a month after childbirth; succeeded by husband. Canonized 1997.

7. (1386) After her son (b. 1370) dies unmarried, Margaret of Denmark, thirty-three and widowed, is created “husband” or permanent regent of both Denmark (her father's kingdom) and Norway (her husband's kingdom); also becomes regent of Sweden 1396; with the power to name her successor, she adopts and renames a great-nephew who succeeds her in 1412.

8. (1415) Joanna II, forty-five, a childless widow, succeeds brother Ladislas as king of Naples; remarries but removes husband 1419; crowned 1421; dies 1435; succession disputed by two adopted heirs.

9. (1425) Blanca, thirty and remarried, inherits Navarre; joint coronation 1429; dies 1441; husband (who lives until 1479) prevents son (b. 1421) from claiming throne.

10. (1458) Charlotte, fourteen, inherits kingdom of Cyprus; marries 1459, joint coronation; deposed 1460 by illegitimate half brother through an Egyptian jihad; dies at Rome 1487.

11. (1474) Catherine Cornaro, nineteen, king's widow, legally adopted by Venetian Republic; after infant son dies, Venetians proclaim her monarch but depose her 1489; dies in Italy 1510.

12. (1474) Isabel the Catholic of Castile, twenty-three and married, claims brother's kingdom and defeats her thirteen-year-old niece Juana in lengthy civil war; reigns jointly with husband until her death in 1504; succeeded by second daughter (b. 1478).

13. (1477) Mary of Burgundy, nineteen, inherits Europe's most powerful nonroyal state; marries eighteen-year-old heir of emperor; dies in hunting accident 1482, succeeded by son (b. 1478).

14. (1494) Catalina de Foix, twenty-four and married, inherited Navarre from brother 1483; joint coronation with cousin at Pamplona; after kingdom invaded and conquered by Spain 1512, they flee to Béarn; succeeded 1516 by son (b. 1503).

15. (1504) Juana of Aragon, twenty-six, “and her legitimate husband” (the phrase used by her mother in 1474) jointly inherit Castile. Abdicates all responsibilities 1506, immediately widowed; legal status creates confusion for forty-nine years; dies 1555 as her son (b. 1500) abdicates.

16. (1553) Mary Tudor, thirty-six, inherits England, marries younger cousin (already with royal status), who becomes coruler without coronation or defined political responsibilities; dies childless 1558, succeeded by half sister.

17. (1555) Jeanne III, twenty-eight, inherits Navarre; dual coronation with husband; repudiates his authority shortly before his death in 1562; governs alone until her death in 1572; succeeded by son (b. 1553).

18. (1558) Mary Stuart, sixteen, sovereign of Scotland since birth, becomes legal adult by marrying French dauphin, giving him crown matrimonial; both her mother, who had governed her kingdom as regent, and her husband die in 1560; returns to govern Scotland 1561; remarries 1565; husband murdered 1566; remarries again but forced to abdicate in 1567 in favor of son (b. 1566); flees to England; beheaded 1587.

19. (1558) Elizabeth I of England, twenty-five, Europe's first female monarch who never married; dies 1603, succeeded by son of Mary Stuart.

20. (1598) Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia, thirty-two, and husband jointly created sovereign archdukes of Habsburg Netherlands by her father, Philip II; childless; loses sovereign status after husband's death 1621 but remains as regional governor until her death in 1633.

21. (1644) Christina of Sweden, inherits father's kingdom at the age of six (1632) and governs by presiding over Council of State at eighteen; coronation 1650; refuses to marry but arranges succession before abdicating 1654; becomes Catholic; dies at Rome, 1690.

22. (1689) Mary II, twenty-seven, crowned as joint ruler of England with usurper husband, William III of Orange; dies childless 1694, succeeded by husband.

23. (1702) Anne, thirty-seven, Mary II's younger sister, inherits England; married to first prince consort without royal honors; no surviving children; dies 1714, succeeded by nearest Protestant relative.

24. (1718) Ulrika Eleonora, thirty and married, acquires Swedish throne over nephew; resigns in favor of husband in 1720 after kingdom refuses joint monarchy; childless; husband outlives her.

25. (1725) Catherine, forty-one, widow of Peter I, crowned 1724, Russia's first official female empress; dies 1727, naming stepgrandson (b. 1716) as heir.

26. (1730) Anna, thirty-four, childless widowed niece of Peter the Great, becomes Russian autocrat by tearing up signed constitution; dies 1740, succeeded by infant son of her niece.

27. (1741) Maria Theresa, twenty-four and married, crowned as king of Hungary under Pragmatic Sanction; also crowned king of Bohemia 1743 (husband holds no legal rank in either kingdom); dies 1780, succeeded by son (b. 1740), her official coregent after husband's death in 1765.

28. (1741) Elisabeth, thirty-two, daughter of Peter I and Catherine (see no. 25 above), becomes Russian autocrat after coup d'état; never marries; dies 1762, succeeded by nephew (b. 1728).

29. (1762) Catherine II, thirty-three, becomes Russian autocrat after overthrowing husband in coup d'état; dies 1796, succeeded by son (b. 1754).

30. (1777) Maria I, forty-two, inherits Portuguese throne; husband (her paternal uncle) receives auxiliary coronation; widowed 1786; incapacitated by illness 1792; son (b. 1766) becomes regent 1799; taken to Brazil, where she dies in 1816.

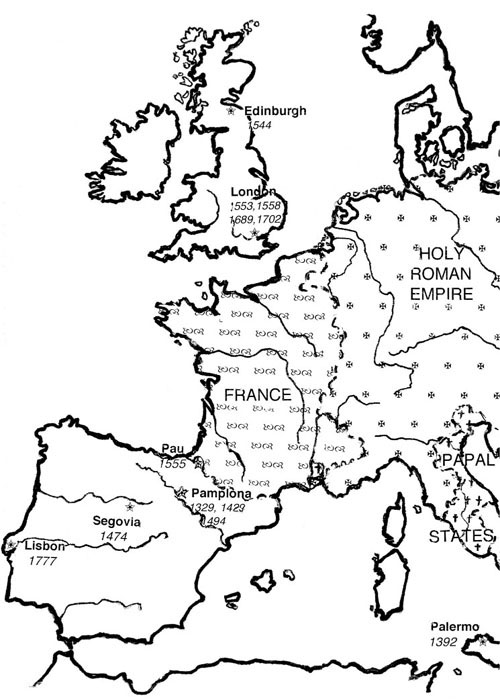

Geographically, outside of a large core zone composed of France, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Papal States, all of which explicitly excluded female rulers, female monarchs were distributed extremely widely across the European continent, as the locations of their official coronation ceremonies demonstrate.

The history of female sovereignty, including the phrases one must use to describe it, involves so many transgressions of prescribed female roles that it seems unwise to impose more theory than the material can support comfortably. Therefore my basic arrangement is organized primarily around the dominant solutions adopted in different eras to the weighty political problems that inevitably resulted from the expectation that all female monarchs would marry. Two caveats must also be entered at the outset. First, as far as possible this book deliberately avoids using the confusing English noun queen to describe female sovereigns. Derived from Old English cwen, meaning “wife of a king,” it collapses the huge difference between its original and primary meaning and a woman who wields supreme monarchical authority with divine approval in her own right. English, like Latin and other major European vernaculars, has no feminine form of king. However, England and many other parts of Europe were ruled by several women who exercised precisely the same authority as male kings and deserve to be called kings. Compounding the confusion, the vast majority of these female kings (except for Elizabeth I of England and two others) also functioned as queens in the original sense because legitimate dynastic reproduction formed a vital part of their responsibilities.

Second, this is not a survey of the history of every type of female authority in every major European state before 1800. That subject is enormous. Aside from so-called soft power, i.e., the informal exercise of influence by women at royal courts, the history of any autonomous hereditary state that lasted more than a century includes at least one wife or close female kin (mother, sister) who exercised formal authority on an interim basis as regents substituting for underaged, absent, or incompetent male rulers. Because the authority of female regents was always delegated and temporary, I do not attempt to survey them en bloc. However, because both the most innovative printed arguments for women's right to exercise political authority and the most extreme pictorial representations glorifying female rule produced in early modern Europe were sponsored by long-serving female regents rather than by women claiming to govern by divine right, I include a chapter profiling the careers and patronage of several culturally innovative female regents who served in major European states between 1500 and 1650: six Habsburg princesses in the Low Countries and Iberian kingdoms and two widows from the grand duchy of Tuscany in France.

My search for pertinent information was made possible largely by the generosity of the Mellon Foundation, which awarded an Emeritus Fellowship in 2008–09 to a septuagenarian who had abandoned this area of scholarship decades ago. The foundation's financial assistance has let me explore places connected with these bygone female rulers, including their palaces; many of the most splendid examples are now museums, although part of the oldest palace, in the small Navarrese town of Olite, is a luxury hotel, or parador. It also took me to many well-stocked national libraries from Lisbon to St. Petersburg (this last founded by a female monarch) and into a few archives, among which the manuscript collection of the venerable medical faculty of the University of Montpellier proved the most useful. Finally, a search for visual representations of women sovereigns has introduced me to such auxiliary disciplines as numismatics and film studies.

My largest debts of gratitude are connected with Northwestern University, my employer for forty years. First and foremost, they go to a former graduate student, Sarah Ross, now at Boston College, who collaborated enthusiastically in an ill-fated joint venture which never saw publication but alerted both of us to the posthumous manipulations of fathers by some of Europe's most ambitious female rulers—a subject that probably deserves a full-length separate study. Other former graduate students have also provided invaluable assistance, especially Peter Mazur and Elizabeth Casteen, whose thesis on Europe's first successful female sovereign breaks fresh ground. Departmental colleagues of long acquaintance have also offered precious guidance. Both Ed Muir and Robert Lerner read and commented most helpfully on early draft chapters; Carl Petry happily translated some Arabic sources concerning fifteenth-century Cyprus, and John Bushnell reassured me that I had not grievously misrepresented eighteenth-century Russia. At Northwestern's University Library, Harriet Lightman, an expert on French regencies turned bibliographer, identified and purchased several invaluable items. Input from the early modern graduate seminar at the University of Chicago has also proved extremely helpful.

Friends living far from Chicago have also helped to shape this essay. Colleagues abroad have provided indispensable assistance and much-needed encouragement: in England, Mark Greengrass; in Paris, Isa and Josef Konvitz, Francine Lichtenhahn, Aleksandr Lavrov, and Robert Muchembled; in Spain, Gustav and Marisa Henningsen and James Amelang; in Portugal, José Paiva; in Austria, Karl Vocelka and his young colleague Karin Moser of the Austrian Film Institute. This work frequently foregrounds numismatic evidence, and it is a real pleasure to thank many unfailingly courteous numismatists, most notably Robert Hoge of the American Numismatic Society in New York, his counterparts at the British Museum and elsewhere in western Europe, and Evgenia Shchukina in St. Petersburg, all of whom tried their best to help an elderly novice with an odd agenda. All erroneous information and unsustainable opinions in this book remain the sole responsibility of the author.