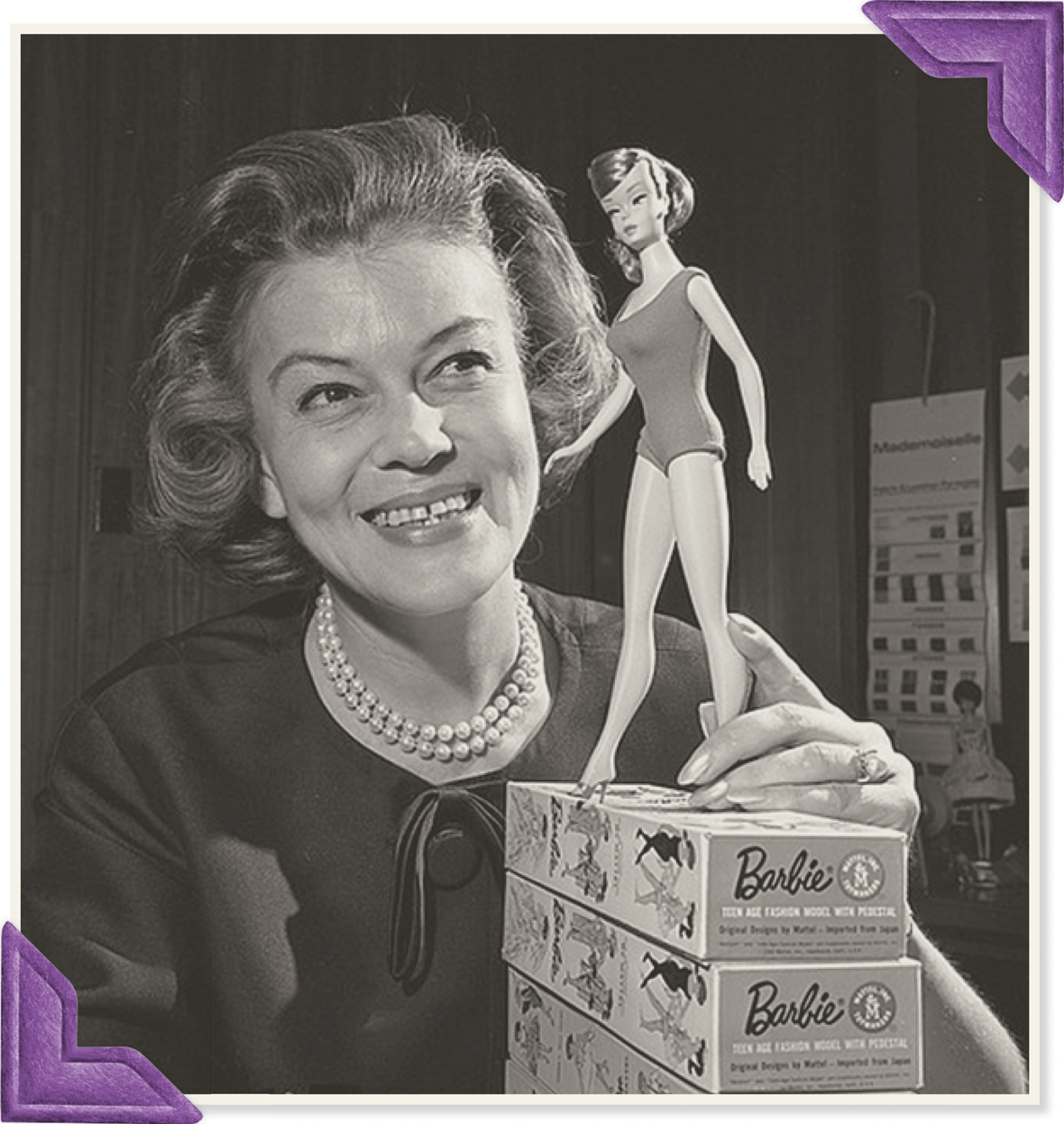

BARBIE QUITE SIMPLY CHANGED MY LIFE. Since 1959, millions of children around the world have fallen in love with the most popular fashion doll ever created. Barbie wasn’t only a stylish toy, she also nurtured imaginations, which was what Ruth Handler had envisioned when she created the eleven-and-a-half-inch “teenage fashion model.”

Of course I was aware of Barbie when she debuted in 1959. You couldn’t miss her. Ruth Handler and her husband, Elliot, had done a masterful job with Barbie’s launch; in magazines, newspapers, or on television, someone was always talking about Barbie. I went to a toy store to check her out, and I can still recall my first in-person glimpse of her, with her sideways glance, wearing her now-iconic black-and-white-striped bathing suit and heels. I remember thinking Barbie looked important.

That turned out to be quite the understatement. Over six decades, Barbie and her friends have spawned an incredible wealth of adventures—many originated from her design team, who created a universe that included an ever-expanding roster of professions, dream houses, modes of transportation, a wide-ranging wardrobe that combined fashion trends with a liberal dose of fantasy, and so much more. Children everywhere embraced this world and enhanced it via the stories they created as they played, which was key to Barbie’s success.

The first Barbie doll, 1959.

Photo by Carol Spencer

For thirty-five years, I was at the center of that universe as a member of Mattel’s design team. It wasn’t a career I had ever envisioned when I was younger, but from that moment in 1962 when I first read Mattel’s advertisement in Women’s Wear Daily, I saw my future, and it thrilled me.

Perhaps that’s because Barbie’s life was the polar opposite of my own: she was the ultimate California girl, while I grew up in Minneapolis, where the winters were gray and seemingly endless. Barbie could take on any profession she desired—she was an astronaut in 1965, four years before the Apollo 11 moon landing—but when I was thinking about a career in the late 1950s, the options available to women largely focused on the “expected” five: nurse, teacher, secretary, shopgirl, and seamstress. My older sister, Margaret, had become a nurse, and all my friends at Washburn High School in South Minneapolis likewise seemed to easily accept these choices. I always knew, however, that I wanted more.

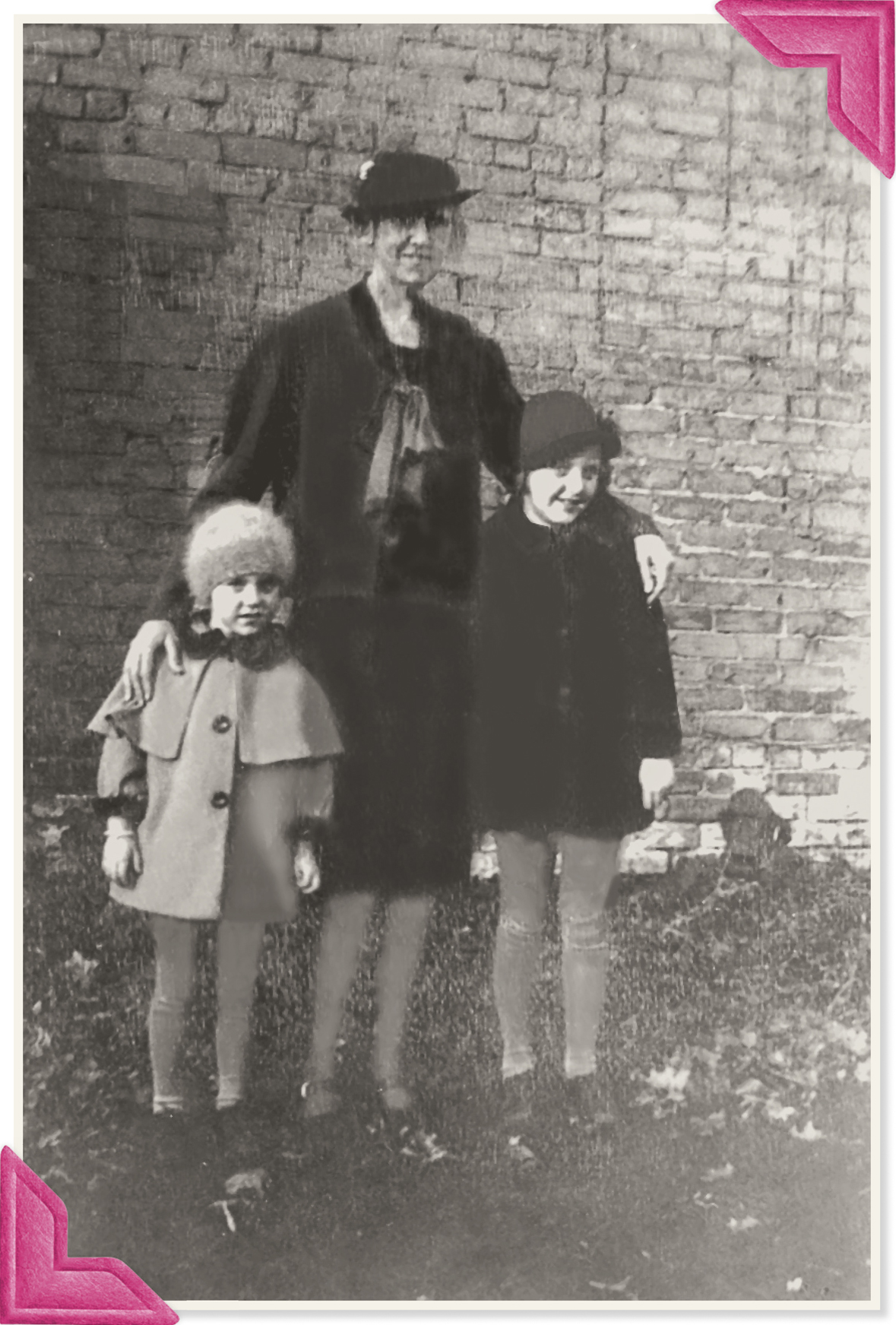

The only exception? I really loved to sew and still do. In 1937, when I was four years old, my father died unexpectedly, and my mother, sister, and I moved from Dallas, Texas, to Minneapolis, Minnesota, to live with my Aunt Lena, Uncle Lincoln, and my grandmother. Getting used to the snow and cold was a big adjustment, but I quickly bonded with my grandmother, who was incredibly talented with a needle and a sewing machine, and she instilled in me a fondness for these skills. I was mesmerized by her ability to create a beautiful dress from pieces of fabric, and as I watched her, my face would inch ever closer to the sewing machine. I can still hear her say, “I will stitch your nose to the garment if you don’t move farther away.”

My sister, Margaret (right), and me with our Aunt Lena, 1937.

Aunt Lena and Uncle Lincoln, who had no children of their own, truly became surrogate parents for Margaret and myself when our mother passed away from a stroke while we were in high school. Eventually the four of us were very happy in that Minneapolis home.

As my high school graduation approached in 1950, however, those expected life choices loomed before me, and I was feeling restless. That’s also because I had found myself somewhat committed to a sixth option: wife and mother. His name was Neil: he and I had dated throughout high school, and everyone around us expected the next natural step—including Neil. His family had decided we would get married after graduation and I would get a job so I could support him while he went to medical school. He had not given me a ring, and no date had been set. Yet increasingly, I didn’t like the idea that my life had been planned out for me.

I want more, I thought.

One Sunday while reading the newspaper, I spied an ad for a seminar highlighting jobs in the fashion industry. I put on my best interview clothes and my bravest face, and I didn’t tell anyone where I was going. The first speaker was a member of the Fashion Group International, Inc., who discussed the fashion design program at the Minneapolis School of Art. She put two words together that I had never heard of as a vocation: fashion designer. It was as though someone had turned on a light. Before leaving the seminar, I filled out an application—and when I returned home, I still didn’t tell anyone.

I watched the mailbox every day for weeks until an envelope with my name on it finally arrived: I had been accepted! That feeling of wanting more suddenly no longer made me feel restless; instead, it was exhilarating.

It was time to tell Neil. His father used to drive us on our dates, he in the front seat, Neil and I sitting side by side in the back seat. Anything I discussed with Neil, his father would be privy to. So I shared my news, telling my fiancé how excited I was about the opportunity and suggesting that we both could go to school, but that meant I would be unable to work and help pay his tuition. But the next day, the decision was made: our engagement was over.

More than anything, I felt relieved. And I couldn’t wait for what was next.

Today the Minneapolis School of Art is known as the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, and in the early 1950s, I was among just 250 students, many of whom were World War II veterans studying on the GI Bill. On most days, I was able to catch a ride with a former GI who decided to study sculpture after he had worked on the restoration of Mount Rushmore. And instead of the sweater-and-skirt combination that had practically become my high school uniform, in college I wore blue jeans most days—just like the guys.

This newfound freedom also came with challenges. I loved studying basic design, color, and painting, though when it was time to take Life Drawing, I discovered I was the only woman in the class alongside thirty older, male students—and, in the center of the room, nude models. I hid behind my drawing board the first few days, until I realized it was silly to be self-conscious. We were too busy learning about perspective, proportion, and shading to be embarrassed or titillated.

Another favorite memory was when Oskar Kokoschka, the Austrian expressionist painter, came to our school to give a seminar. My textbook called him “a giant of modern art,” and I read everything I could find about him. He was in his sixties when he visited us, cutting quite the dramatic figure with his white hair and keen eyes.

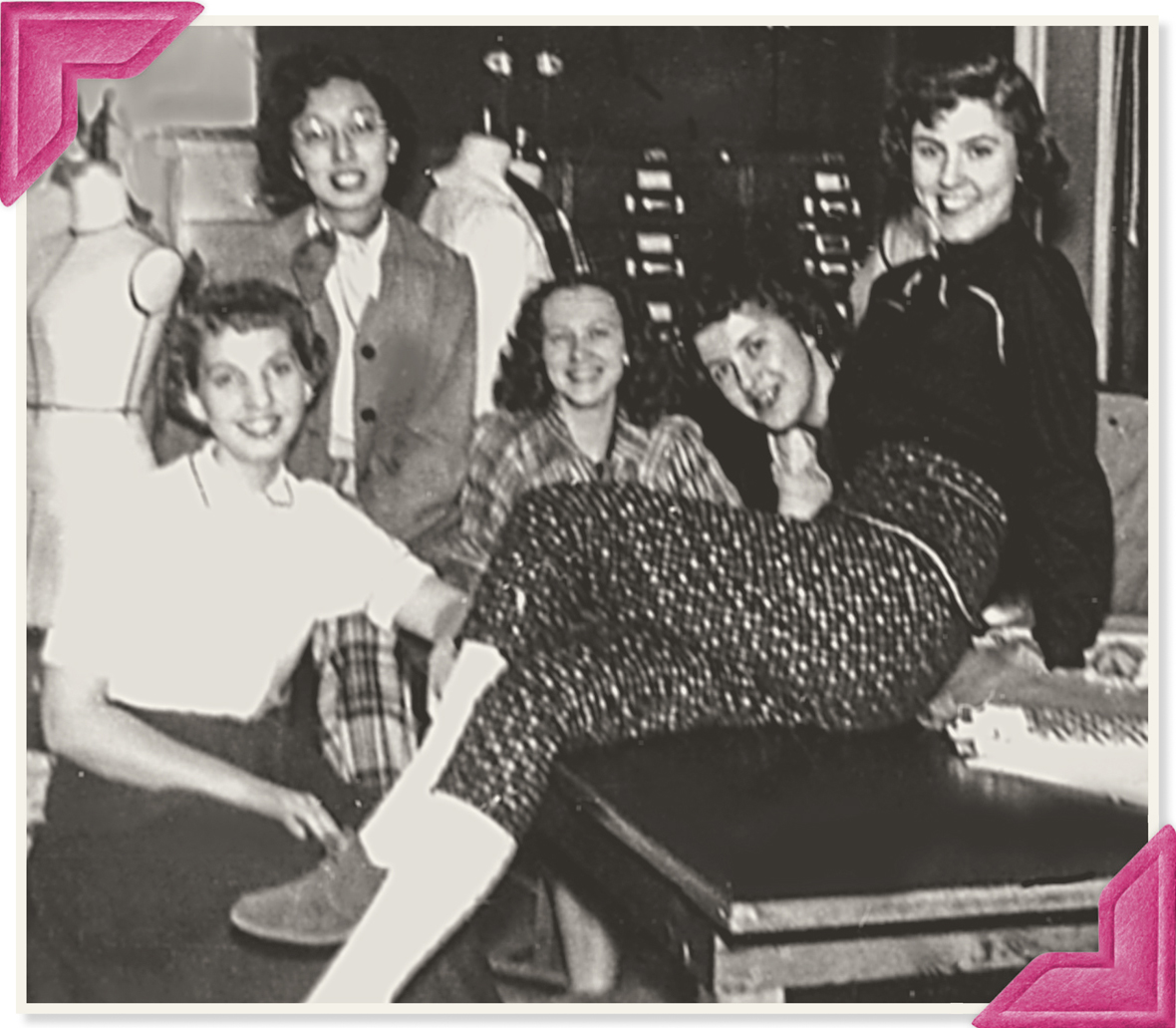

Modeling one of my ensemble designs for my classmates at the Minneapolis School of Art, c. 1954.

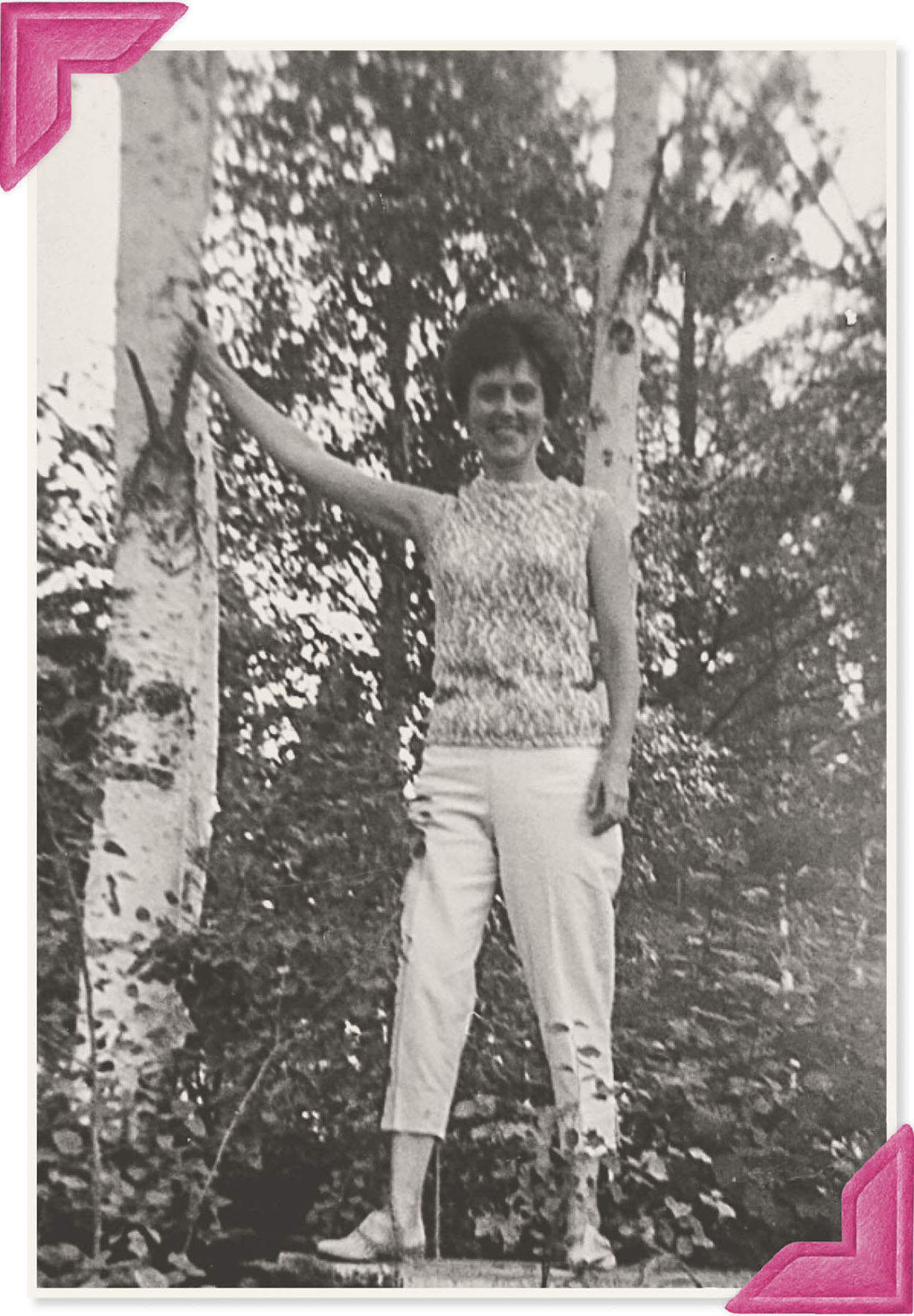

On vacation in northern Minnesota, 1958.

I arrived at the lecture early and sat in the front row. The title of his talk was “The Art of Seeing,” and he sketched the entire time he spoke, occasionally holding up his pad to illustrate a point he was making. Toward the end of his speech, he held up a sketch—it was me! I almost didn’t recognize myself, but then he turned to me and quietly said, “You are special.”

The moment was more than thrilling. It felt like a blessing from someone I considered larger than life. Never before had I thought of myself as special. But Oskar Kokoschka pushed me a little further on my path; I was going to prove I was special to everyone—including myself.

At the beginning of my senior year of college, a notice was posted that the application process was about to kick off for Mademoiselle magazine’s annual guest-editor contest. While Vogue was considered the epitome of high fashion, Mademoiselle focused more on the lifestyle of smart, independent young women; contributing authors included Joyce Carol Oates and Truman Capote. Meanwhile, the guest-editor program was truly prestigious, with an alumni list that included Sylvia Plath and, from my year, Joan Didion.

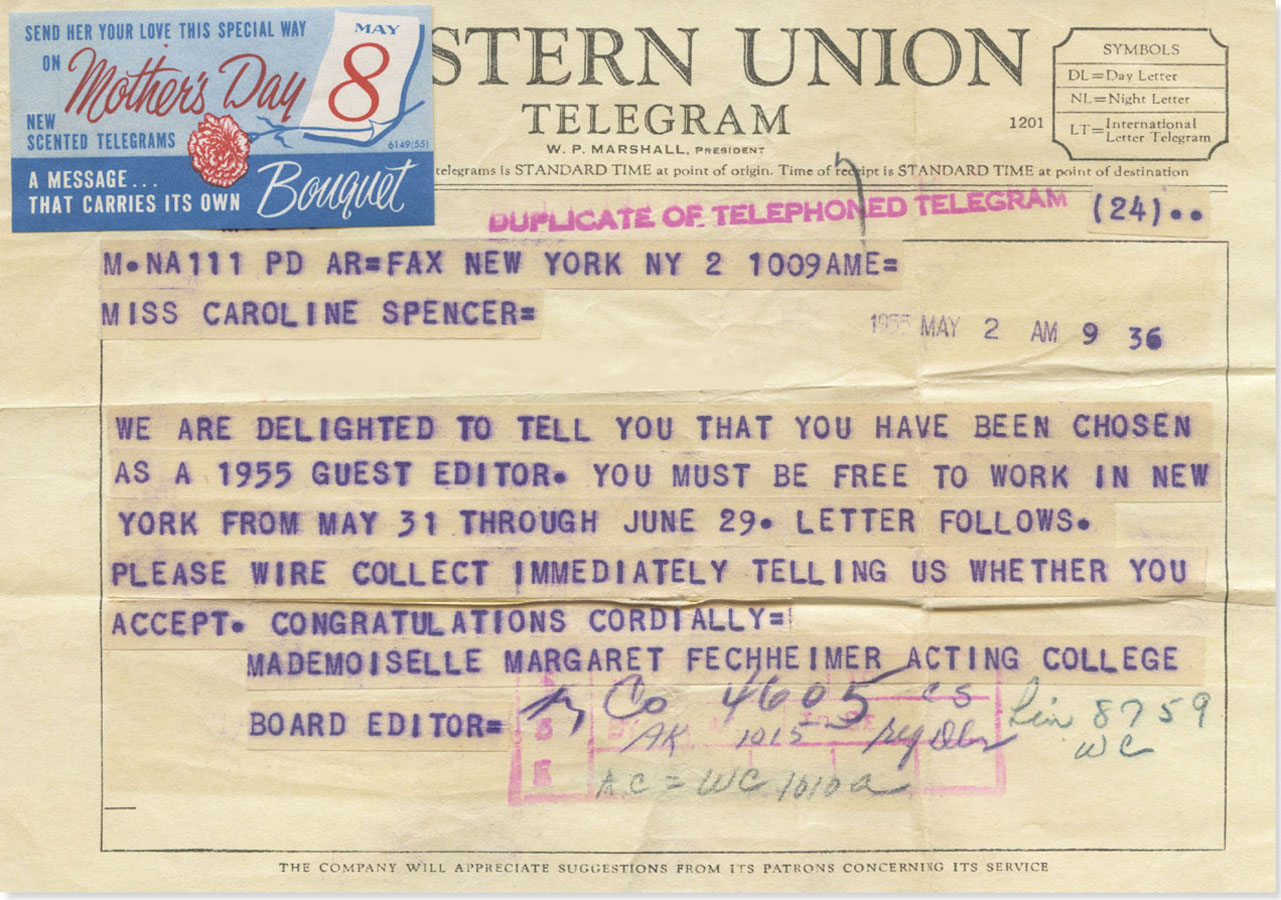

Entrants submitted four essays over the course of their senior year; but with more than thirty-seven thousand applicants and only twenty guest editor spaces, did I even have a chance? My first essay won a ten-dollar prize, and I allowed myself to hope. In early May, just prior to graduation, the telegram arrived: “We are delighted to tell you that you have been chosen as a 1955 Guest Editor.”

How did I feel? Special, indeed.

Naturally I was thrilled, but also more than a little apprehensive. Mademoiselle informed the winning guest editors that we had to be free to work in New York between May 31 and June 29. I had never lived away from home or outside Minneapolis, at the time a relatively small city. Not until the telegram arrived did it occur to me that living in New York for a month might feel overwhelming. Then again, after all those years of feeling restless and wanting more—this was my chance.

The congratulatory telegram Mademoiselle sent me, May 1955.

In June 1955, instead of walking across the stage to receive my diploma, I’d checked into the legendary Barbizon Hotel for Women in New York City, living and working in a city that was overwhelming, but exciting too. While walking on Fifth Avenue, I found myself always looking up—at the green mansard rooftops of the Pierre and the Plaza, or the art deco edifices of Bonwit Teller and Tiffany & Co.

Our class of twenty talented “mademoiselles” was nothing less than a dreamlike experience. We were invited everywhere: to the home of the famed cosmetics mogul Helena Rubinstein, who devoted an entire room of her penthouse apartment to Salvador Dalí paintings, and to stand at the podium in the General Assembly room at the United Nations, which had opened its headquarters on Manhattan’s East Side just a few years before. We wore our best formals while dancing with West Point cadets in the ballroom on the rooftop of the St. Regis Hotel. And everywhere we went, we were photographed as though we were debutantes or celebrities. It was about as far from Minneapolis as you could get.

Even the work was tinged with glamour. We each had to produce an article for publication, and I asked the magazine’s fashion editor, Kay Silver, if I could interview Pauline Trigère, whose work I appreciated for its combination of innovative construction and clean, chic lines. To my utter delight, Kay granted my wish, and soon enough I was standing with Pauline Trigère in her workroom in the Garment District. It was my first look at a professional design studio, with its large tables for pattern cutting, mannequins for draping (Miss Trigère’s preferred design process), and a live-fit model on standby. I was hooked.

Colors from the Standard Color Reference of America, 9th Edition, used for early Barbie fashions.

Used with permission: Standard Color Reference of America, 9th Edition, 1941–1981

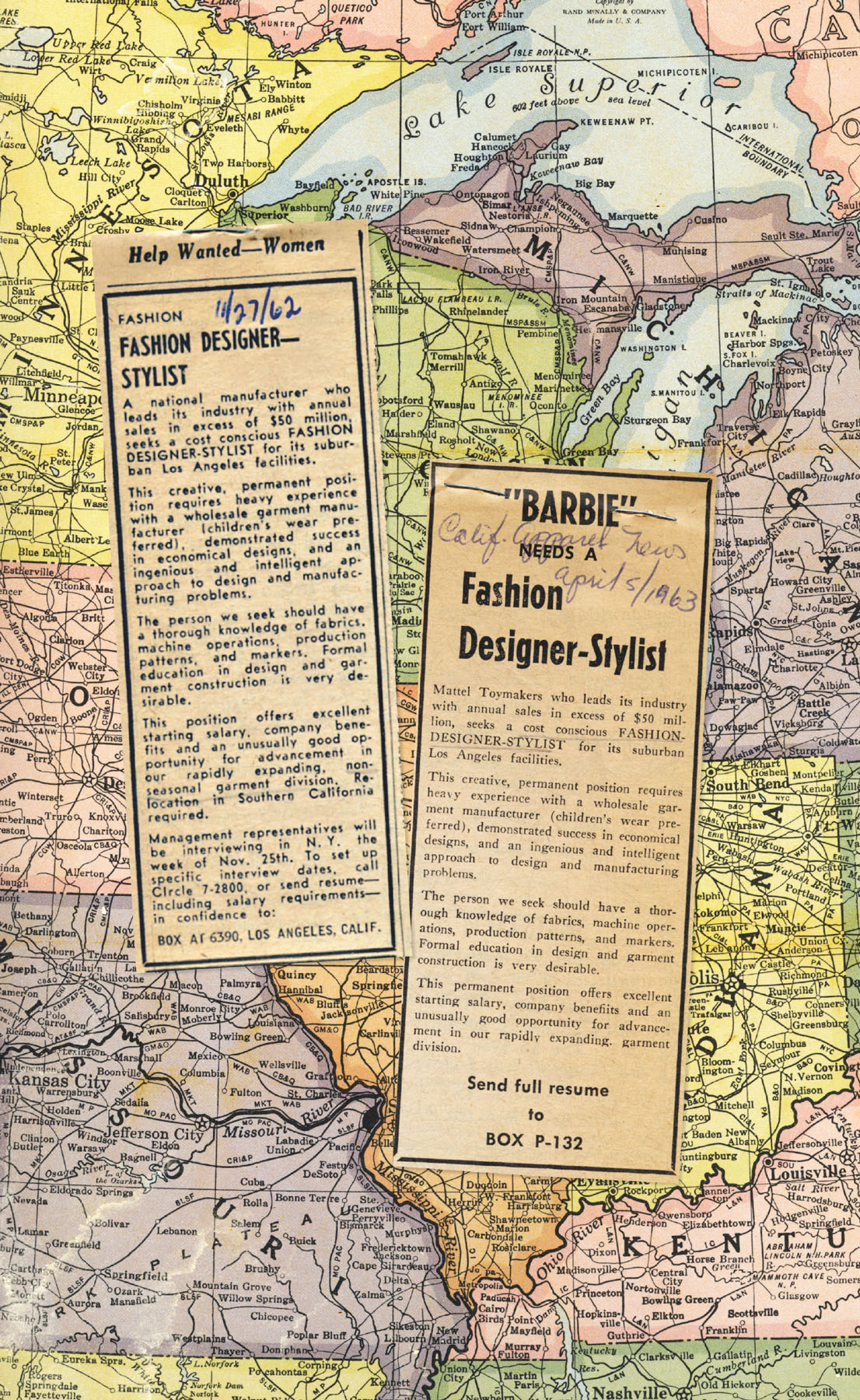

The ad Mattel placed in Women’s Wear Daily (left) when the company was looking for a fashion designer-stylist, November 1962. I saw the second ad for a Barbie fashion designer-stylist (right), in California Apparel News, April 1963.

Used with permission: Rand McNally map c. 1960; Women’s Wear Daily ad, November 1962; California Apparel News ad, April 1963

During our interview, Miss Trigère (as I always called her) dispensed terrific advice that I still follow: a pretty sketch is only the beginning; a good fashion designer also considers the execution of that design and how the personality of the fabric will play a role. No one element is more important than the others. She also encouraged me to, above all, be true to myself. Throughout my thirty-five years designing for Barbie, I never strayed from this philosophy.

That month in New York flew by, and it was time to think about a full-time job. I headed back to Minneapolis, where Wonderalls Co., a wholesale garment manufacturer, needed a children’s wear designer. These days it would be impossible to think of someone fresh out of college designing a complete clothing line, but that’s exactly what I did, everything from tops to coveralls and even bathing suits, for girls and boys.

After a few years at Wonderalls Co., I needed a change—not only because designing children’s wear could be rather limited but also because of Jerry, the owner’s son. We had dated for a while, but when he broke up with me—our religions were incompatible, unfortunately—I knew it was going to be awkward seeing him every day. I also realized that I once again had no desire to be dependent upon a man. My first priority had to be my career. I started sending out my résumé.

A Milwaukee company called Junior House needed a designer for “misses sportswear,” the designation for clothes for teenage girls then. It was just what I wanted: a new job in a new city, and no more children’s clothes.

Junior House was located in a big, drafty building on Milwaukee’s South Side, but I quickly learned every aspect of the business, as my new boss, Lee Rosenberg, gave me a crash course on everything, from fabrics and production patterns to machine operations. I was installed in a studio above the factory, where I would sketch a design, cut and drape it on a mannequin, and then cost it out. If Lee approved, I would make the pattern and run it downstairs, where the production team would crank out my design in every size and color, a dozen pieces each. I loved watching my design go from sketch to completed garment so quickly. My designs also came in on budget and sold well, a combination every garment manufacturer appreciates.

I couldn’t know it at the time, but the knowledge and experience I gained at both Wonderalls Co. and Junior House ultimately would prove to be the perfect foundation to join Mattel as a Barbie fashion designer-stylist.

But first I had to get the job.

When I saw the ad in Women’s Wear Daily in November 1962, it didn’t mention Barbie or Mattel; rather, it was a blind ad for a fashion designer-stylist, yet I read between the lines and was able to discern both the company and product. I also realized how perfectly I matched every element the ad was seeking. “Heavy experience with a wholesale garment manufacturer”? Check. “Children’s wear preferred”? That fit as well. “The person we seek should have a thorough knowledge of fabrics, machine operations, production patterns, and markers.” Thanks to my experience at Wonderalls and Junior House, I was confident I could handle these tasks with ease. Perhaps best of all, two words jumped out at me: Los Angeles. Sunny California suddenly seemed like the perfect change from Milwaukee, and working on Barbie, already the world’s most popular toy, seemed like an irresistible idea.

I sent my résumé for consideration, but didn’t receive a response. In the meantime, thoughts of Los Angeles continued to beckon. One day, in a pure leap of faith, I decided a move to California was exactly the change I was seeking. I didn’t have a job, but even if Mattel didn’t hire me, I knew Los Angeles was a hub for fashion manufacturers. Aunt Lena accompanied me on the road trip and helped me settle into my first LA apartment—I also hedged my bets and selected a home not far from Mattel’s headquarters. The sun shined every day, and the Pacific Ocean was just twenty minutes away. I was in heaven.

Before I left Milwaukee, I had asked for my mail to be forwarded, but still no word from the company advertising for a fashion designer-stylist. Then one day in 1963, I was sitting at my kitchen table in Los Angeles, reading a trade paper, and I couldn’t believe my eyes: “Barbie Needs a Fashion Designer-Stylist.” The ad listed all the same requirements as the previous blind ad, but this time it was no secret: Mattel needed someone to design for Barbie. Thrilled to learn more about the position, and that it hadn’t been filled, I applied the same day.

And soon enough, a response. Actually, make that two responses: At roughly the same time Mattel replied to my submission to the ad in the California paper, my forwarded mail from Milwaukee also arrived, and there was Mattel’s reply to the résumé I had sent after seeing the blind ad in Women’s Wear Daily. Amazingly, both letters included the same request: Could I come in for an interview on April 12 at 11:00 a.m.?

Charlotte Johnson, the manager of the Barbie design team, in 1963, the year I met her.

Mattel Archival Photographs

Ruth Handler, Barbie’s creator, in the early 1960s.

Mattel Archival Photographs

This was fate, I thought. My decision to move to Los Angeles had paid off.

On Friday, April 12, 1963, just before 11:00 a.m., I arrived for my interview at Mattel’s California headquarters. I was determined to get this job.

Jerry Fire of Mattel’s human resources department greeted me in the lobby. I still remember thinking how handsome he was. We walked back to his office, he offered me a seat, and then he opened his desk drawer: inside, I saw what looked like a gun.

He saw the look on my face and burst out laughing. “This? It’s a toy,” Jerry said, waving it around nonchalantly and showing me that it only fired blanks.

So this is what it’s like to work at a toy company, I thought.

My interview with Jerry actually was quite brief. He had heard the story of my dueling résumé submissions, and during this process Mattel evidently had decided I was more than qualified for the job. There were just two hurdles to get past: from that same desk drawer, Jerry took out two Barbie dolls, one blond and the other brunette, both sporting the same bubble-cut hairstyle. With them, he handed me a packet of instructions. I had two weeks to create a set of test fashions; the dolls should be dressed in my finished designs, and I needed to present patterns and sketches. “And be sure to keep track of your time, because we’ll pay you for it,” Jerry added.

Back in my apartment, I put the dolls on my kitchen table and spread out the instructions. The first challenge was how different it would be to design for a doll instead of designing for a child or young woman. Barbie had been created on a one-sixth scale of the female form, and while the math for creating patterns was easy enough, finding prints suitable for her smaller size could be difficult; even the smallest, most delicate flower on a child’s dress would seem gigantic on an eleven-and-a-half-inch doll. I also had to take into consideration the perception of Barbie as the quintessential California girl. Whatever I designed needed to evoke that ideal.

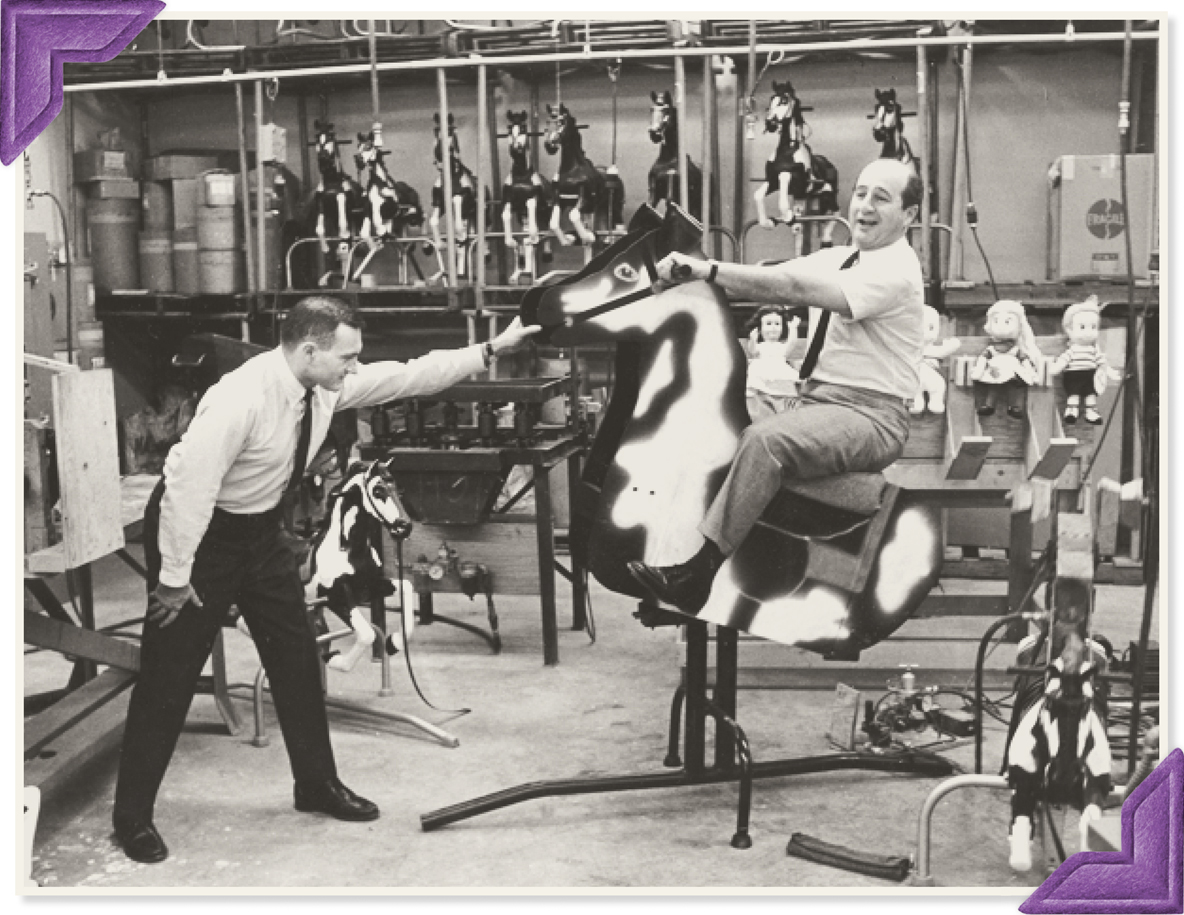

Jack Ryan (left), head of research and design, and Elliot Handler (right), Mattel’s co-founder, test out Blaze, Mattel’s talking rocking horse, c. 1961.

Mattel Archival Photographs

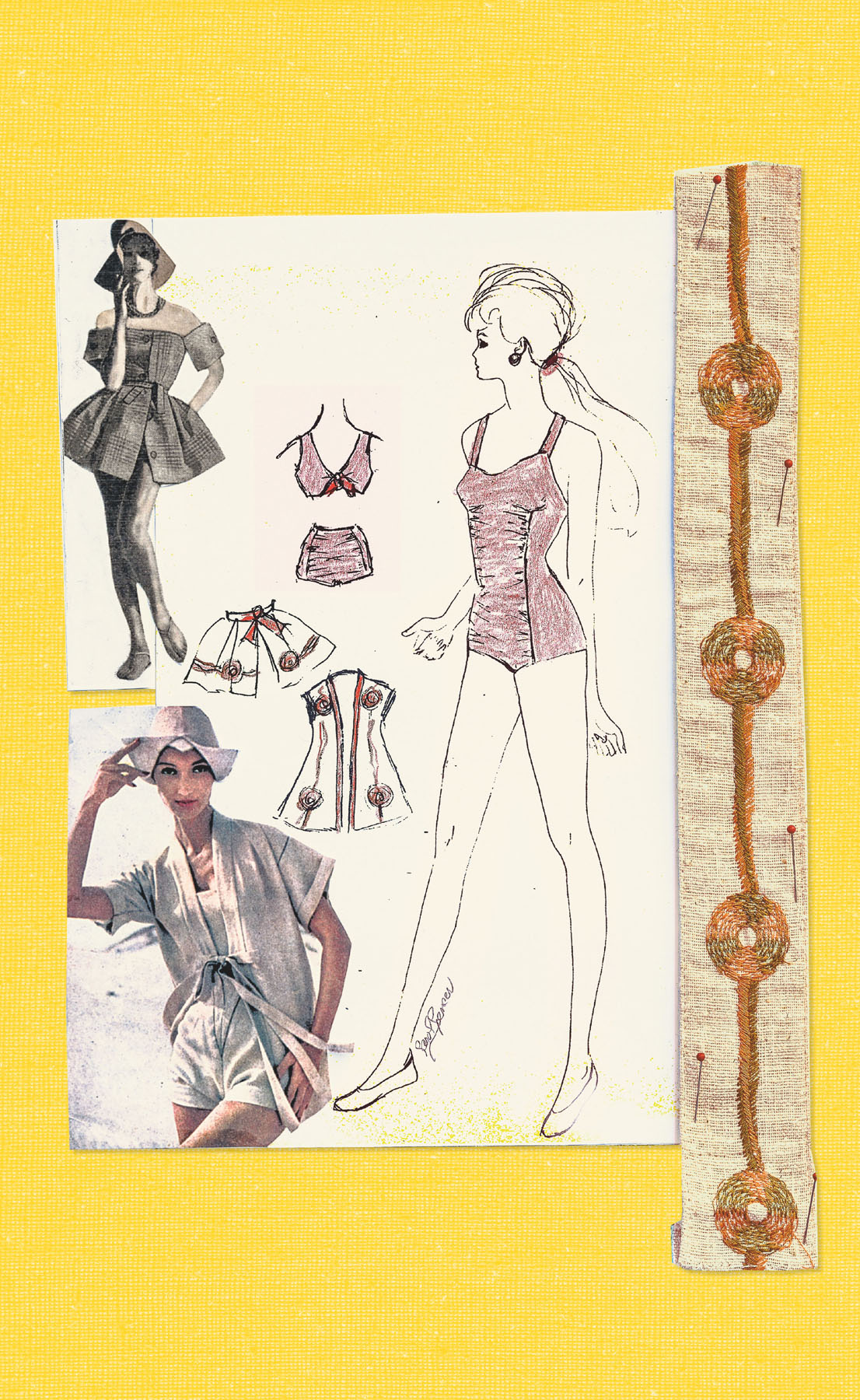

That’s when I decided that a swimsuit and matching cover-up was the answer. If Mattel had any concerns that I might not understand the California lifestyle, I would prove that wrong from the outset. I dived into my considerable collection of fashion magazines and tore out every image of a stylish swimsuit to produce an inspiration board. From there, I started sketching and created a small collection that felt chic and on trend and also more than a bit feminine. That’s what I saw when I looked at Barbie, and I wanted that to come through.

As I started thinking about the fabric I would use to render my designs, I remembered a children’s look I had created at Wonderalls, and I dug through boxes until I found it—I no longer cared about the clothing design, but the fabric was perfect, a beige cotton with miniature lollipops that I had custom designed. Both the scale of the print and the feel of the fabric were perfect for the cover-up. For the swimsuits themselves, I created a one-piece and a two-piece style, both in a soft red that coordinated perfectly with a color found in the lollipop print. My finished Barbie dolls looked fun and chic, and definitely like California girls. Most important, I absolutely loved the process.

Completing the test fashions was merely the first hurdle. My follow-up meeting two weeks later was with the woman who already had become a bona fide legend in the history of Barbie. Charlotte Johnson had been a freelance fashion designer who also taught at what later became known as the California Institute of Arts. Early in 1959, Ruth Handler recruited Charlotte to work on her top secret doll project, and she ultimately played an integral role in Barbie’s look. Charlotte was inspired by the runways of Paris and New York, combining that chic aesthetic with the feeling of the California lifestyle to create the twenty-two fashions that comprised Barbie’s 1959 debut wardrobe. Charlotte knew the doll better than almost anyone—except, perhaps, Ruth Handler herself—and she was about to evaluate my designs. Of course, the moment was incredibly intimidating. I wore my best interview suit with a hat, gloves, and a matching bag, and I carried my finished Barbie dolls, one in each hand, somewhat nervously. Still, I knew what I had created was the absolute best of my skills and imagination.

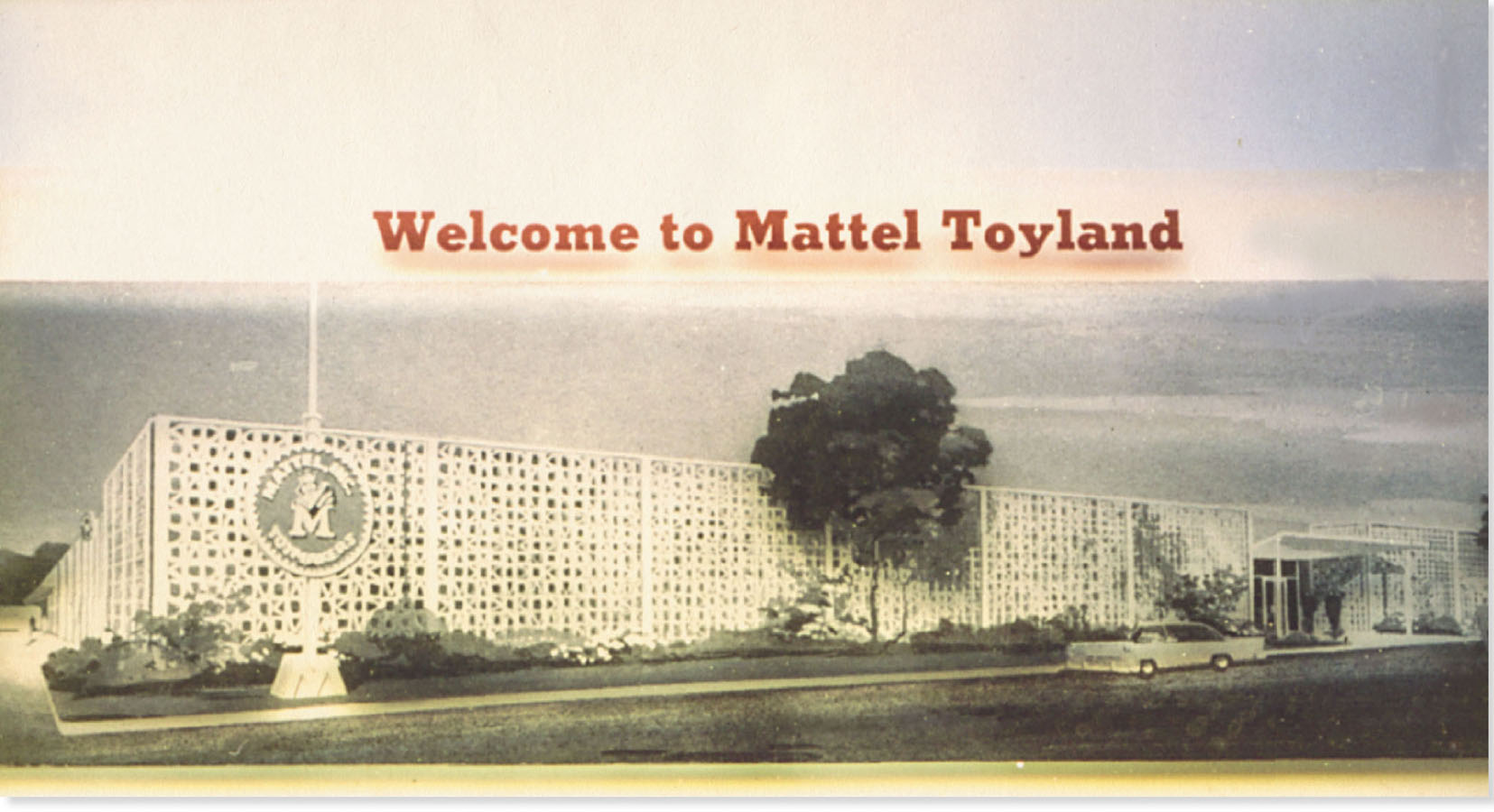

Mattel as it looked in the early sixties, when I started working there.

Mattel Archival Photographs

Jerry Fire ushered me back into his office for this step in the interview process, and then Charlotte walked in and joined us. My first memory of meeting her was that she was very tall and quite stylish. I felt good about my test designs, but in Charlotte’s hands, who could tell? I didn’t say a word as she turned the dolls over and over, closely examining every detail—not just the styles themselves but also the construction, the seaming, even the fabrics I had chosen. After what seemed like an eternity, Charlotte rendered her verdict: “I have no objection to hiring you,” she said, her words revealing no enthusiasm for my designs. And with that, she walked out of the room.

My first thought: What just happened? Then Jerry Fire was beside me again, escorting me to another room to take a personality and aptitude test, the final step to becoming a Mattel employee in those early years. Once that was complete, he was shaking my hand, a big smile on his face. It took me a moment to realize that I had passed both tests—Charlotte’s and Mattel’s—and had gotten the job. All of a sudden, I was smiling along with Jerry.

The rest of that day was like a dream in which I sort of floated along. I couldn’t stop grinning, because I had achieved exactly what that second ad had asked for: I was a fashion designer-stylist for Barbie.

People talk about fate as an abstract idea, but in that moment, I fully embraced what it meant. The two advertisements I’d responded to had serendipitously asked me to come in and interview on the same day at the same time. How could that not be destiny?

The inspiration board I created before I started designing the “test” outfits for the Mattel job, along with the fabric I used for the cover-ups.

Photo by Carol Spencer

I wanted my outfits to look as fun and chic as Barbie was. I succeeded, because they got me the job!

Photo by Carol Spencer