Chamberlain, Daladier, Hitler, Mussolini, and Ciano, Munich Conference, September 1938.

Chamberlain, Daladier, Hitler, Mussolini, and Ciano, Munich Conference, September 1938.

IT IS CURIOUS with what clarity one remembers great events of the past, even from those long-ago days before twenty-four-hour-a-day television and web news became a constant background to daily life.

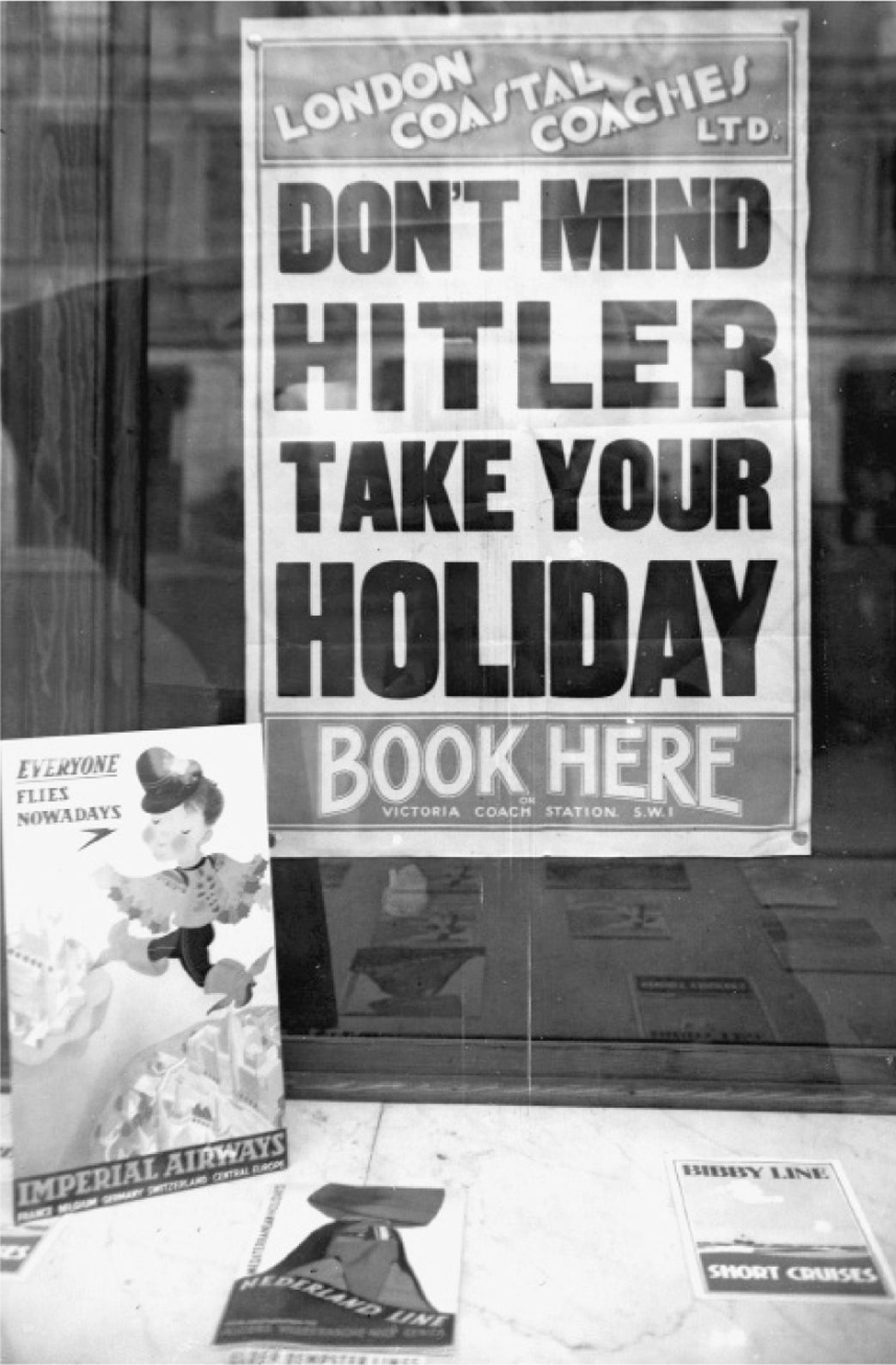

In the 1930s and throughout the war it was a ritual in many, if not most, households in the United Kingdom to sit down after supper and listen solemnly to the nine o’clock news from the British Broadcasting Corporation. There were no alternative radio channels; however bloodcurdling the events of the day, news was fed out in small doses by the BBC and read in a tone as dry as a sermon. It was no accident that the BBC had originally required those reading the news on the radio (or “wireless,” as it is called in the United Kingdom) to wear nothing less than formal evening clothes while doing so. Listening to the news then was a secular rite from the most humble home to Buckingham Palace, and although the BBC got much of its news from the government, it was generally trusted. Far from making the news exciting the British and the French governments were to produce calm at all costs and to downplay, or even deny, any crises. Keeping calm was seen as a patriotic duty, even as one crisis after another led inexorably to war—panic was the enemy.

My father, Vincent, a rumpled Bohemian who had followed his brothers into the film business, did not panic easily, if at all, perhaps because he was born in the last years of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a place where crises were constant, but never taken seriously. The old Viennese joke might have served as the motto for the fading empire: “The situation is desperate—but not serious.” Despite threats from Berlin and rumblings of war over Danzig and the Polish Corridor in August 1939, my father did not, as so many other people in England already had, cancel his plans for our summer holiday on what was then still called, as if it were another world, “the Continent.” For years he had spent the month of August at the unpretentious Hôtel de la Bouée, on the Plage de la Garoupe on the Cap d’Antibes, owned by his friends the Vials, whose daughter Micheline was the same age as me. Although Micheline and I were only six, it was my father’s wish, expressed strongly and frequently in his fluent, inimitably Hungarian-accented French, that we should get married one day, thus assuring him of a permanent nest on the Cap d’Antibes in his old age.

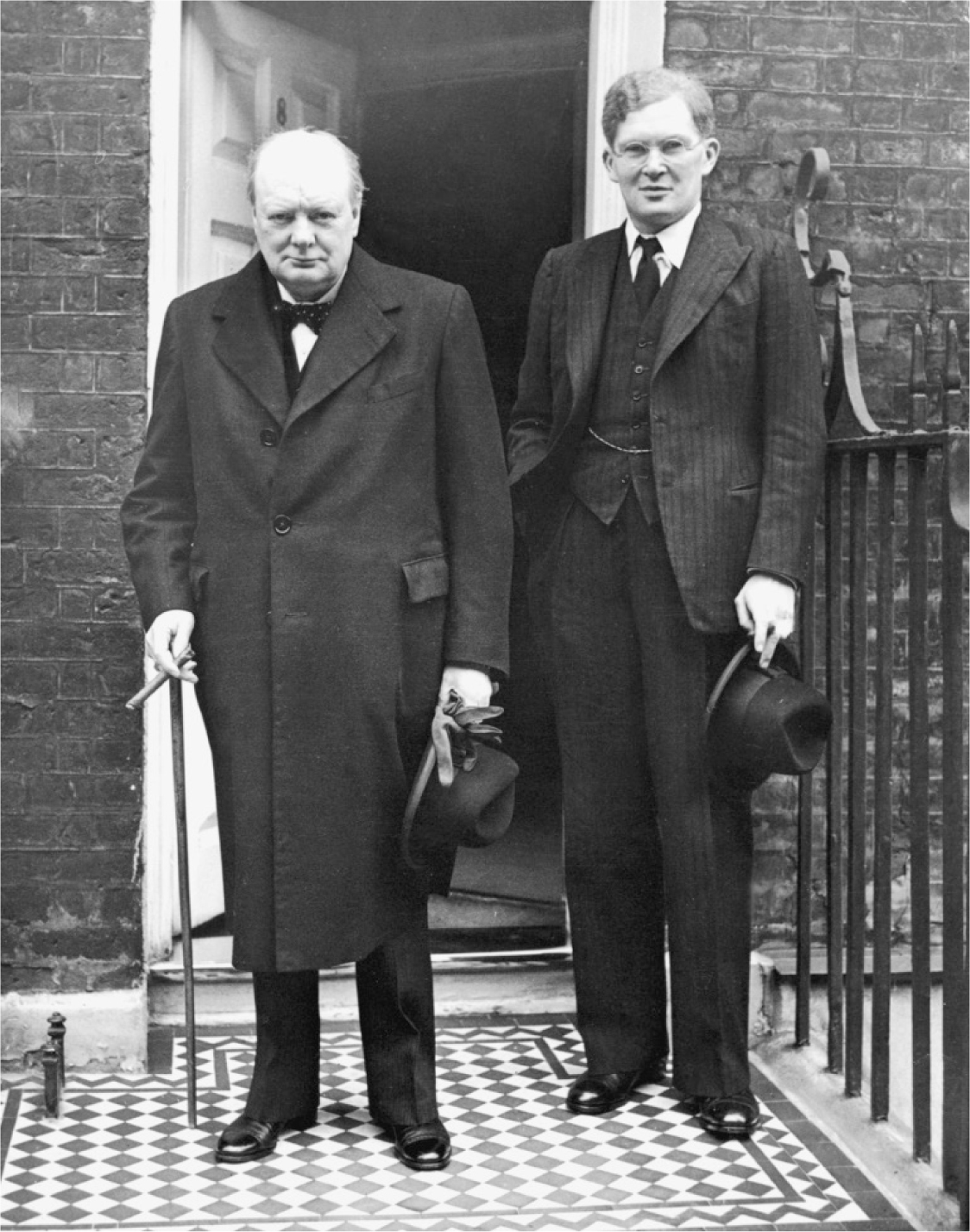

Pleas came from his eldest brother, my uncle Alex, the head of the Korda family and a benevolent though demanding dictator who in the words of one admirer “looked like a Renaissance prince, and spent like one,” or from people who were in the know like one of Winston Churchill’s loyal friends, the political strategist and canny financial adviser Brendan Bracken, to stay put until the crisis was resolved, but my father ignored them. His stately, yearly progress from London to Paris and then on to Antibes, was not something he would give up merely because of threats of war from Hitler. He had survived the First World War, serving in the Austro-Hungarian infantry, as well as the Communist revolution in Budapest that came in the wake of defeat, then the White counterrevolution that brought to power Admiral Miklós Horthy, the first Fascist and for a time the leading anti-Semite in Europe. Having lived through war and the collapse and breakup of an empire, my father treated with indifference seismic geopolitical events that set other people to canceling their reservations. When my mother, a blond, glamorous successful English stage actress, and normally a cheerful and unflappable person, expressed her concern, he merely said, “Don’t be silly, Gertrude, vat the hell you know about it?”

Winston Churchill and Brendan Bracken.

All the same, as Vincent sat beneath a beach umbrella reading a copy of Le Petit Niçois in the morning while he dipped a croissant in his café au lait and lit his first cigarette of the day, events that August must have seized his attention—he was not a Central European for nothing.

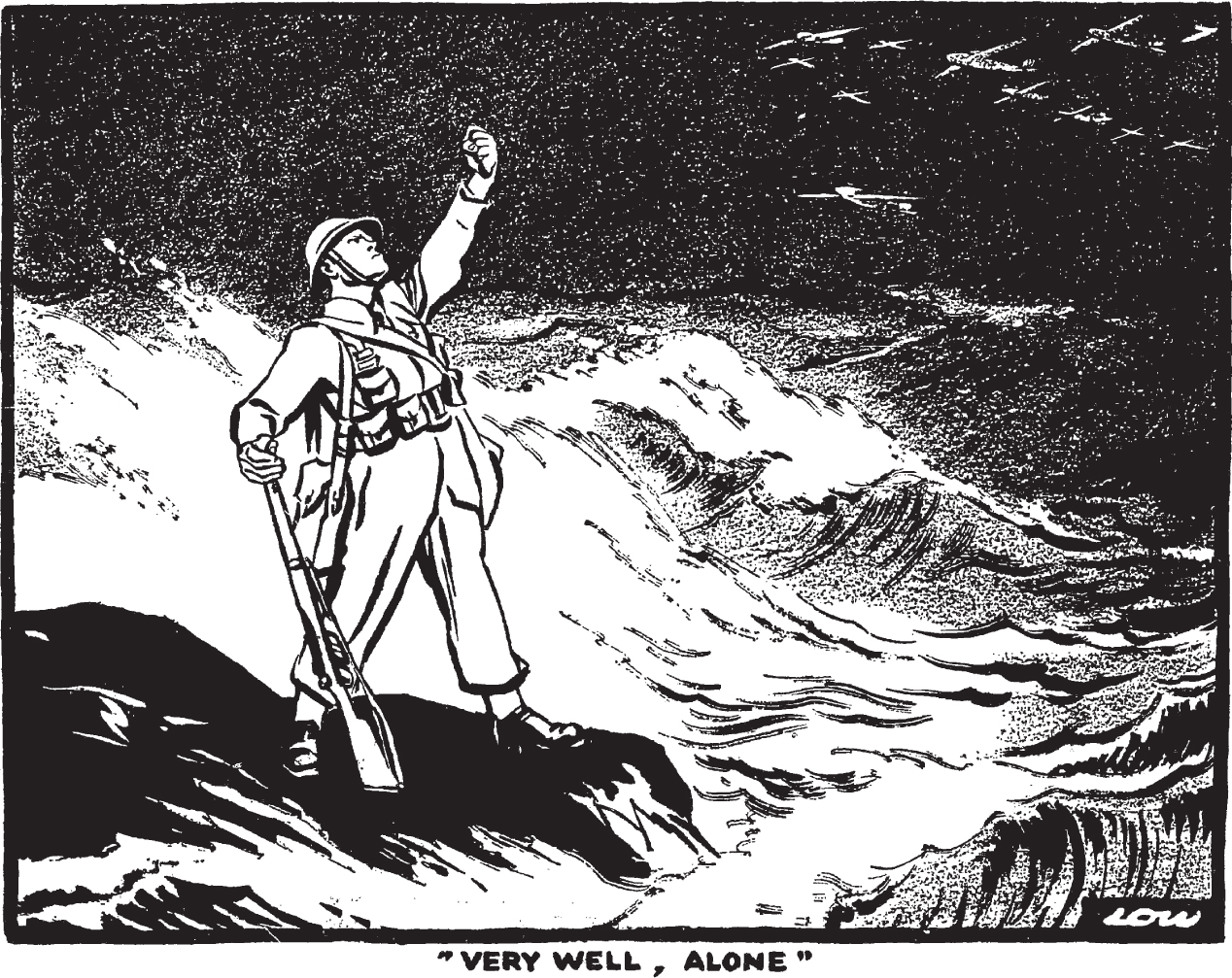

Less than a year earlier at the height of the Czech crisis in September 1938 the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, had addressed the nation on the BBC and remarked, “How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing.”

But these people were not “far-away” to my father, who had been born when what was now Czechoslovakia had still been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the southern half of Poland as well. The Czechs, the Poles, and the Austrian Germans were not people about whom my father knew “nothing.” They were people who had served as he had in the multinational Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Army.*

What my father read in the papers while my mother slept late and Micheline and I played on the beach under the supervision of my nanny, Nanny Low, caused him and Monsieur Vial, Micheline’s father, to chat somberly and at length over more coffee, like doctors discussing a gravely ill patient. Monsieur Vial and my father had both fought in the Great War, as it was still then known, although on different sides, and both of them could recognize from experience the warning signs of war.

It is perhaps significant that the popular song one heard played everywhere in France that summer on the radio or the gramophone was “Tout va très bien, Madame la Marquise,” that French comic classic about an aristocratic lady on vacation calling home to see how things are going in her absence only to be told by her servants of one disaster after another, each described as “a little incident, a nothing,” culminating in the suicide of her husband and the burning down of her château, every horrific step to ruin celebrated by the cheerful refrain

Mais à part ça, Madame la Marquise,

Tout va très bien, tout va très bien.

(But apart from that, Madame la Marquise, everything is going just fine.)

My mother, whose French was fluent and perfect thanks to a childhood in a French convent school, took to singing this constantly, like the whole French nation as it tumbled step by step toward exactly the catastrophe everyone feared most.

The French premier Edouard Daladier, known to his supporters as “the bull of the Vaucluse” after his birthplace, more because of his stocky, portly build than from any bull-like degree of fierceness, seemed dazed by the steadily mounting threats from Berlin against Poland. Daladier had represented France at the Munich Conference in 1938, when the British and the French had forced France’s ally Czechoslovakia, in a triumph for Hitler, to give up the Sudetenland (and with it the Czech line of defenses) to Nazi Germany. As his aircraft approached Le Bourget on his return, Daladier was alarmed to see below him an immense crowd, the largest since Lindbergh had landed there in 1927, and drew the conclusion that he was going to be lynched by his angry countrymen for abandoning the Czechs. When the aircraft landed and the door was opened, Daladier was momentarily shocked speechless to discover that they were there to cheer him for bringing back peace. Turning to an aide he whispered in savage contempt, “Mais quels cons!” (A close English equivalent would be “What assholes!”) Daladier might not live up to his nickname, but at least he was a realist who knew that he had caved in shamelessly to Hitler.

Chamberlain, French foreign minister Georges Bonnet, and Daladier.

In the nine-hundred-year-old tradition of mistrust between France and England the person Daladier blamed for this was Neville Chamberlain, not Hitler. Ironically Chamberlain has passed into history as the ultimate appeaser, his tightly rolled umbrella the symbol of spineless surrender, but in fact he was a man of far greater will power, energy, determination, and moral authority than Daladier, a tough-minded politician with a firm grasp on his party, a solid majority in the House of Commons, and the full support of the king and queen. His flaw was not pusillanimity; it was a lethal combination of vanity and pig-headedness.

When Graham Stewart wrote his splendid book about the relationship between Churchill and Chamberlain, he called it Burying Caesar, and it was an insightful title. Between May 1937 and May 1940 Chamberlain bestrode the British political world like a colossus. He was “masterful, confident, and ruled by an instinct for order . . . but his mind, once made up [was] hard to change.” Like Caesar he seemed beyond challenge, even beyond criticism, master of all he surveyed. Majestic, calm, determined, he did not listen to criticism, or encourage it from those around him—he had entire confidence in his own judgment and, more important, in the rightness of his cause, and always presumed he stood on the moral high ground. Coupled with his dislike of foreigners—he was contemptuous of Frenchmen, Russians, and Americans, not just Germans—Chamberlain had dragged a reluctant Daladier into the betrayal of Czechoslovakia, but unlike the French premier he was proud of what he had done.

When Chamberlain waved the Anglo-German declaration above his head to those who greeted him at Heston Aerodrome in September 1938, and declared to the crowd in front of 10 Downing Street, “I have returned from Germany with peace for our time,” he felt supremely confident—indeed except for a small group of naysayers consisting mostly of Churchill and his few supporters, Chamberlain was hailed not only in Britain, but around the world as a statesman-hero. The New York Times spoke for most of the world the day after Chamberlain’s return: “Let no man say that too high a price has been paid for peace . . . until he has searched his soul and found himself willing to risk in war the lives of those who are nearest and dearest to him.”

It was not that Chamberlain liked Hitler—in fact, he had described him as “the commonest little dog”† after their first meeting—but he had looked Hitler in the eye and decided he could trust his word. He had seen in Hitler an ordinary man who had made good, much like Chamberlain himself, neither a smooth, supercilious diplomat nor an aristocrat. Chamberlain himself was the grandson of a man who had labored as a shoemaker as a child in Victorian England like Dickens in his “blacking factory,” and the son of a man who had made his fortune manufacturing screws in industrial Birmingham, yet who almost succeeded in winning the prime ministership. Joseph Chamberlain’s second son, Neville,‡ was a tough negotiator and a gifted politician, but he had the successful businessman’s conviction that he could tell at a glance whether a man’s word was his bond or not.

When it turned out that Hitler’s was not, even when accompanied by his signature—the Führer occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia with a brutal show of force in March 1939—Chamberlain finally had to face the fact that Hitler could not be trusted. He moved at once to respond to Germany’s aggression with a hasty and incautious guarantee to come to Poland’s support in case it was attacked by Germany, and dragged an ever more reluctant Daladier along with him, thus placing France and Britain in the direct path of Hitler’s next foreign policy move.

German diplomacy moved immediately into the familiar ascending Wagnerian chorus of threats, saber rattling, arbitrary deadlines, and shrill lies, alternating with assurances of good behavior in the future if the Führer got what he wanted at once. These tactics had set European nerves on edge from 1936 to the early months of 1939, securing for Germany the Rhineland, Austria, the Sudetenland, and now the rest of Czechoslovakia without a shot fired. This time there were two obstacles in the way, however. The first was the Poles themselves, who stubbornly, and as it turned out self-destructively, refused to negotiate even small issues with the Germans. The second was Neville Chamberlain, who could neither forget nor forgive that Hitler had broken his word.

Daladier might respond to Hitler’s duplicity with a weary, Gallic shrug, but Chamberlain was personally affronted. Nonetheless, he did very little to speed up the glacial pace of British rearmament, and he hesitated to take the one step that might have made sense—for Britain and France to secure an alliance with Soviet Russia, which would have confronted Hitler and his generals with the dreaded “war on two fronts” that had eventually undermined Germany in the Great War. Step by step he and Daladier stood by helplessly as events swirled out of their control.

Chamberlain’s political archenemy former Prime Minister David Lloyd George might contemptuously dismiss the prime minister as “a good Lord Mayor of Birmingham in a lean year,” but Chamberlain was more than that—he was a man so convinced of his own strength, wisdom, and virtue that he failed to understand the degree to which his cautious diplomacy had ensured just the war he had sought so hard to avoid.

Thus matters stood in those first, sunny weeks of August 1939 as we, like most families, took our holiday, since France then virtually closed down in August, as it still does. Monsieur Vial was not an ardent supporter of Daladier, who had accepted a cabinet post during Léon Blum’s Front Populaire in 1936, and was therefore a little too radical§ for his taste, though Daladier was hardly “a man of the left.” My father, partly influenced by his eldest brother, Alex, and by Brendan Bracken, was a supporter of Churchill rather than Chamberlain, insofar as he took any interest at all in British politics. Vincent, unlike Brendan and Alex, was a man of leftish sympathies, and for that reason Alex had made him responsible for dealing with the film unions at the London Films studio in Denham.

In the ordinary course of things Churchill would have been too far to the right about social issues to appeal to my father, but at the same time he admired Churchill’s firm stand against Hitler, and understood far better than most Britons did at that time how evil and dangerous the Nazis were. His experience of living under Horthy’s Fascist regime in Hungary in 1919 and 1920 had given him a clear understanding of just how brutal the Nazi regime was in Germany. Besides, from 1933 to 1939 he was in constant touch with old friends, film people, and artists fleeing from Austria, from Germany, and from Czechoslovakia because they were Jewish, or on the left, or both.

Admiral Horthy enters Budapest, 1919.

He and my uncle Alex strove mightily to get their old friend and trusted doctor Henry Lax and his family out of Vienna in 1938, and at dinnertime in our house on Well Walk, near Hampstead Heath in London, there was a constant stream of polyglot arrivals from the Continent on their way to New York or Los Angeles thanks to the Korda brothers, men and women with odd accents like my father’s who preferred to speak Hungarian or German with him and French to my mother. They had the haunted look of people who have just witnessed a bad accident, people with aggressive charm and formal manners who had grown up with the Kordas in Túrkeve, or had been to university in Budapest with Alex, or loaned him money, or worked with my father on film sets in Vienna, Paris, or Berlin. Most of them were relieved to be in England, but still determined to put the Atlantic between themselves and Hitler if possible, not just the English Channel.

My father hardly needed the newspapers to tell him about what was going on in Europe: old ladies in Vienna after the Anschluss forced to get down on their knees and scrub the pavement in front of their apartment building with their toothbrush while Brownshirts—and often enough their own neighbors—jeered and kicked them, Jews and men of the left disappearing into concentration camps throughout Germany, life savings expropriated, businesses taken over and “Aryanized,” apartments, artwork, jewelry confiscated, synagogues and books burned, shop windows shattered. It was already a long trail of suffering, humiliation, and cruelty about which nobody wanted to hear, and that neither the British nor the American government wanted to address for fear of having to accept hundreds of thousands of Jews who were not world famous doctors and scientists like Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein, or film stars like Louise Rainer, or successful playwrights like Ferenc Molnár, or nuclear physicists, or the kind of people who could get a job of some kind at any movie studio in Hollywood.

Jews being forced to scrub the pavement, Vienna, 1938.

The Korda brothers never bothered to mention that they were Jewish to their wives or children—no doubt as Hungarians they were already exotic enough when they arrived in England in 1932 without adding another layer—but that is not to say that they ignored what was going on, or what was likely to come.¶ Apart from his friendship with Churchill, who worked for London Films in the thirties, Alex was also a friend of Major-General Sir Stuart “Jock” Menzies, KCB, KCMG, DSO, MC, chief of MI6, known in government circles as “C,”# and used his innumerable European contacts to procure information for British intelligence, as well as giving jobs in the London Films offices overseas to covert MI6 agents. In New York City he rented much more expensive office space than he needed for London Films in Rockefeller Center to give “cover” to a number of well-dressed men and young women whose knowledge of the film industry was insubstantial. There were secrets that the three brothers kept from their wives, and many secrets that Alex kept from his investors, but there were no secrets among the brothers themselves.

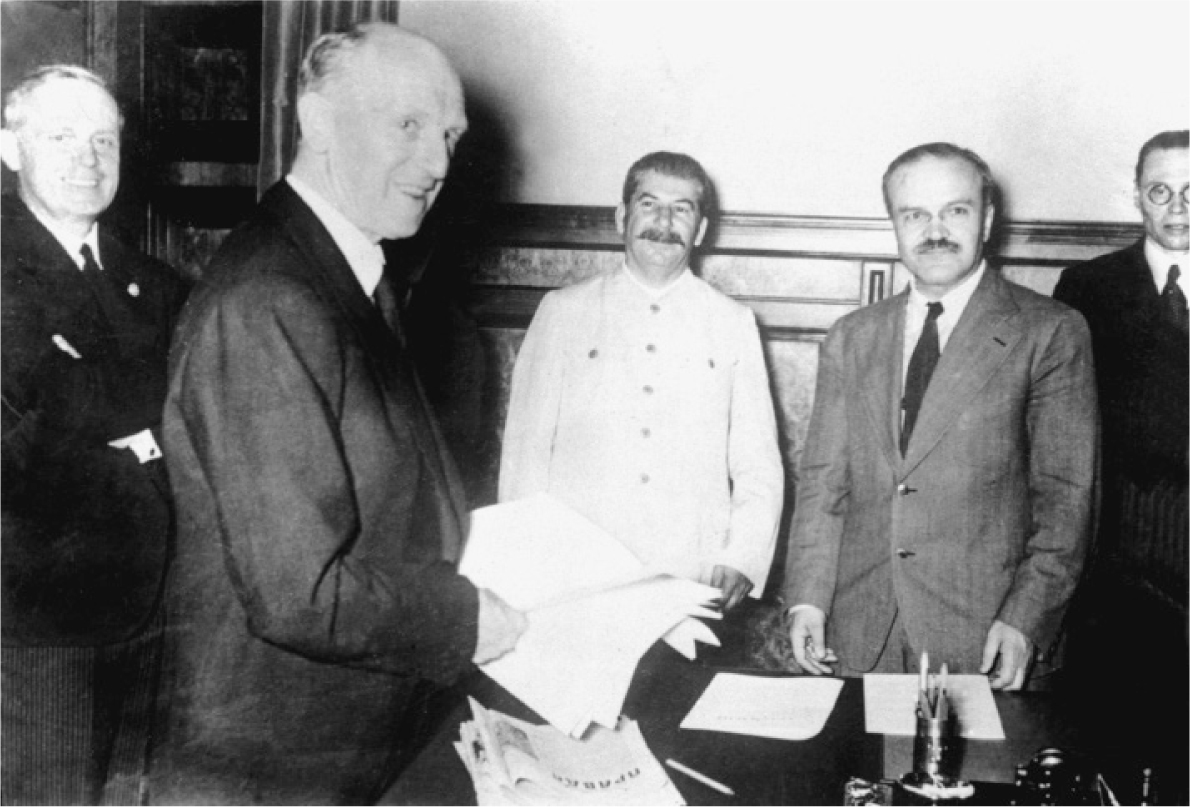

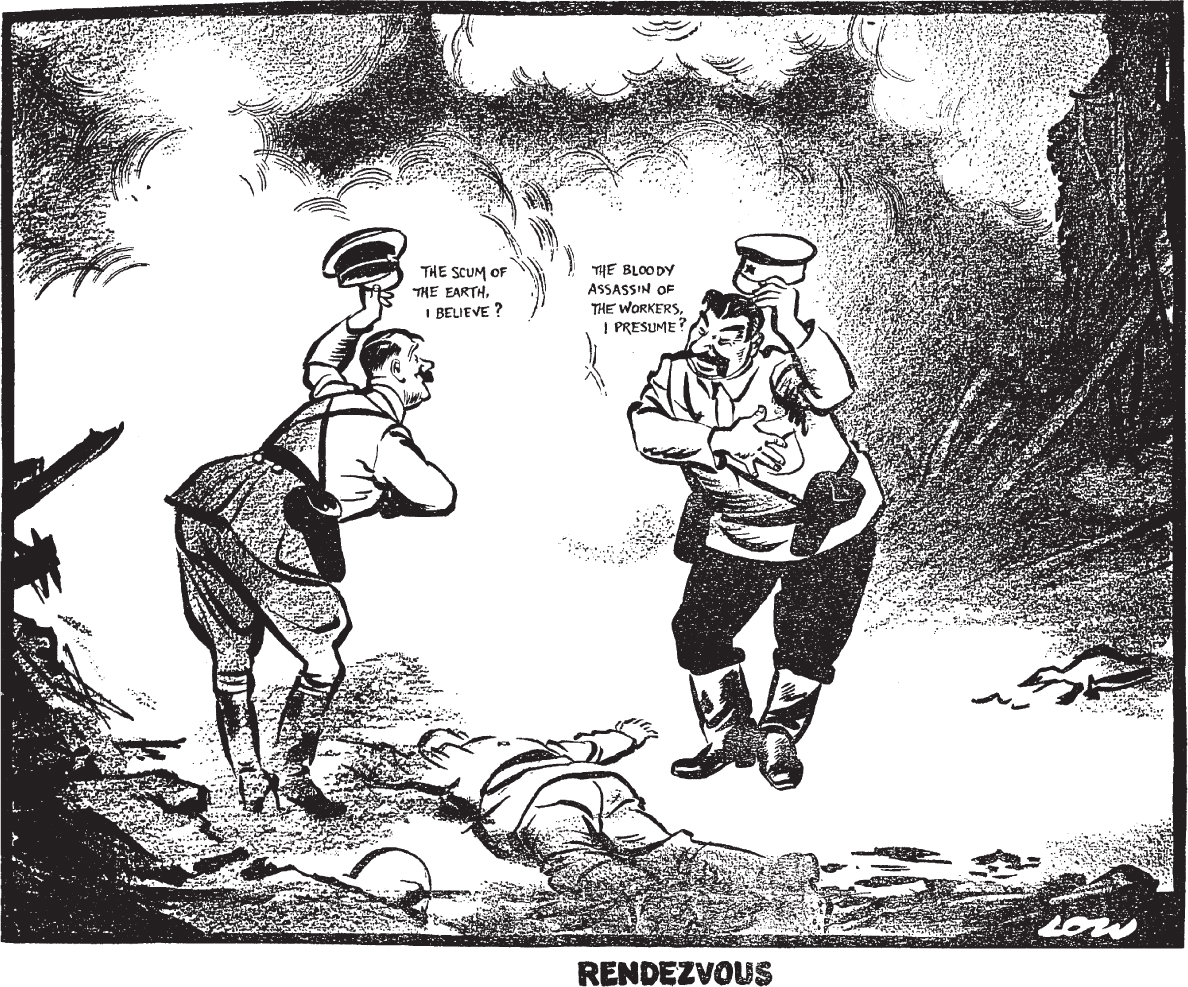

Vincent can therefore have had no doubt about the meaning of the headlines on August 24 announcing the bombshell signature of a nonaggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union, negotiated in secret while the Anglo-French delegation was still meeting in a leisurely way with Soviet officials in Moscow. It says everything about this failed and halfhearted attempt to secure a last-minute alliance with the Soviet Union that the head of the British delegation was the aristocratic Admiral the Hon. Sir Reginald Aylmer Ranfurly Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax, KCB, DSO, JP, scarcely a name likely to appeal to the proletarian sympathies of officials in Stalinist Russia. The appointment of Sir Reginald was symptomatic of the lack of enthusiasm on the part of the British and the French governments for any sort of formal alliance with the USSR. In France those on the right told each other, sotto voce, “Mieux vaut Hitler que Staline” (better Hitler than Stalin), and even in Britain there were people of the same opinion, though less likely to say so aloud. In the end any possibility of an agreement with the Soviet Union to defend Poland was doomed in advance by the Poles’ refusal to allow Soviet troops to cross the border in case of German aggression, and by Chamberlain’s dislike of the idea of Stalin as a partner: “I must confess to the most profound distrust of Russia,” he wrote frankly.

This doubt communicated itself to Stalin, who responded by dismissing Maxim Litvinov as people’s commissar for foreign affairs, replacing him with Vyacheslav M. Molotov. Although a Bolshevik, Litvinov was urbane, charming, worldly and had a good sense of humor. He had lived in England, was married to an Englishwoman, and counted H. G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw among his friends. He was also a Jew, as was his wife, Ivy, so the Germans would have found it difficult, if not impossible, to negotiate with him. Molotov was not only a famously tough bargainer, without a trace of charm or humor, but a gentile.

This sudden change should have come as a warning to everyone that Stalin was preparing to make an agreement with Hitler, but it did not. Soviet politics was a mystery even to experienced politicians, “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma,” as Churchill put it. Hundreds of thousands of people had been swept away to execution or the Gulag in waves of “purges” over what seemed like minor points of Marxist doctrine or because of Stalin’s paranoid suspicion, with the result that even quite significant changes in the Soviet government seemed arbitrary and whimsical to outsiders, a game of “musical chairs” on a vast scale in which the losers were shot. In Berlin, however, the signal was not missed—it takes one dictator to recognize a subtle message sent by another—and the replacement of Litvinov by Molotov was seen at once by Hitler as an invitation to negotiate the hitherto unthinkable, an alliance between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia.

On August 23 Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and Molotov signed this bombshell of an agreement in Moscow, with a beaming Stalin looking on as if he were about to give away the bride. When the news broke the next day, along with the Soviet decision to end negotiations with Britain and France while their negotiators were still in Moscow, almost everybody but the most dogged of appeasers realized that war would break out soon. It would begin when the harvest was in, my father told Monsieur Vial, and Monsieur Vial did not disagree. This was old-fashioned folk wisdom in every European country.

August 27, 1939, the signing of the nonaggression pact between Germany and the USSR (far left, Ribbentrop; center, Stalin; right, Molotov).

Vincent booked us on the “Blue Train” home, for once giving up the chance to break his journey and spend a few days in Paris, and made his farewells to old friends on the Riviera like Marcel Pagnol, the playwright, whose hit play Marius my uncle Alex had made into a film in 1931. Until then Vincent had been living peacefully as a painter in Golfe-Juan, a little seaside town near Vallauris, but Alex had not been happy with the set designs for Marius, which had been borrowed from those of the play. On the grounds that my father at least knew what the Old Port in Marseille looked like, he sent for him (in the Korda family Alex’s wishes were commands) to design something more suitable, thus setting Vincent on the path to a new career.

Like everyone else Pagnol was depressed at the idea of having to fight the Germans all over again only twenty-one years after they had been defeated at the cost of 1,350,000 French lives. Like most of the French he hoped without much confidence that things could be “arranged” at the last minute, just as they had been at Munich, without descending into total war. If the politicians were unable to do so—a lift of the eyebrows, a shrug—then France would merely have to retire behind the Maginot Line and wait to see what happened.

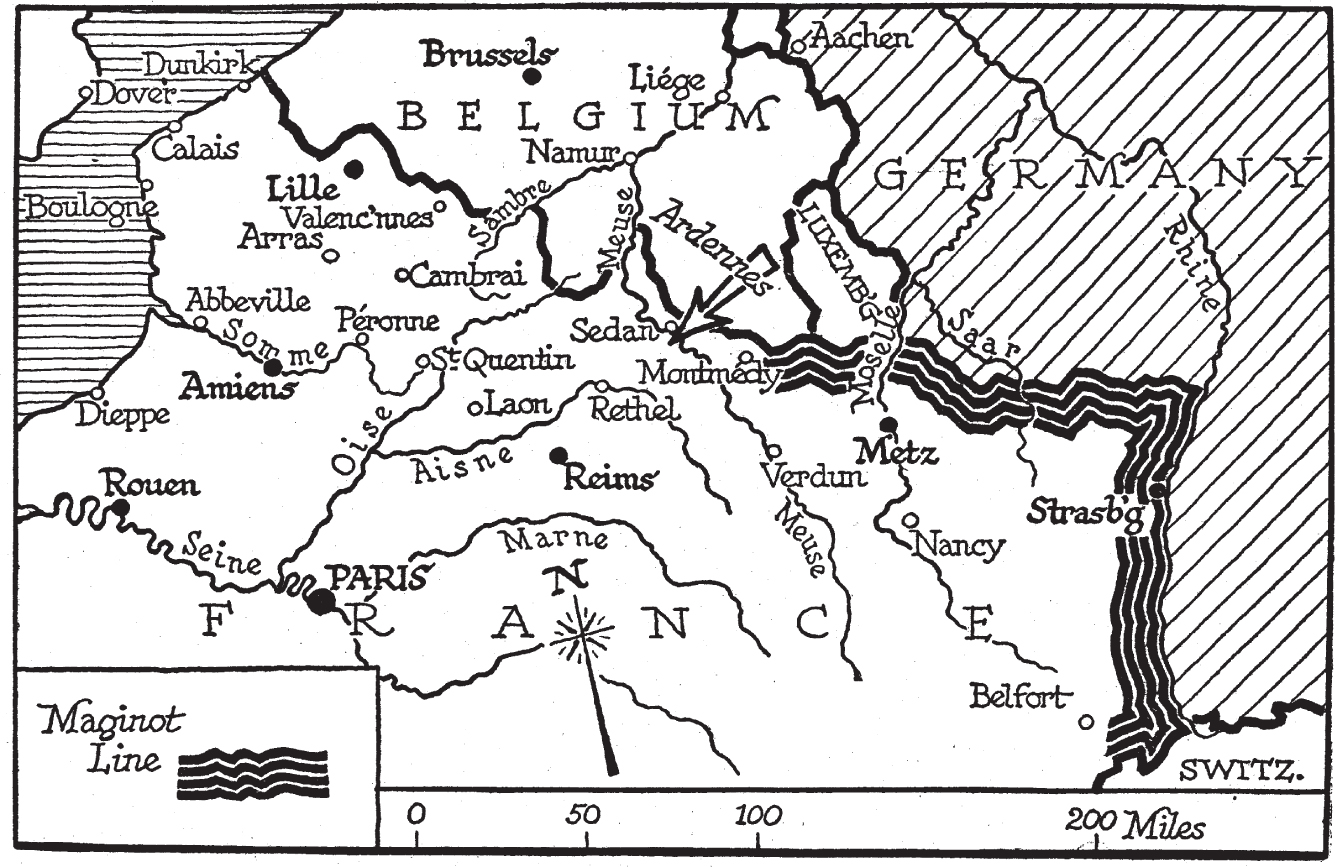

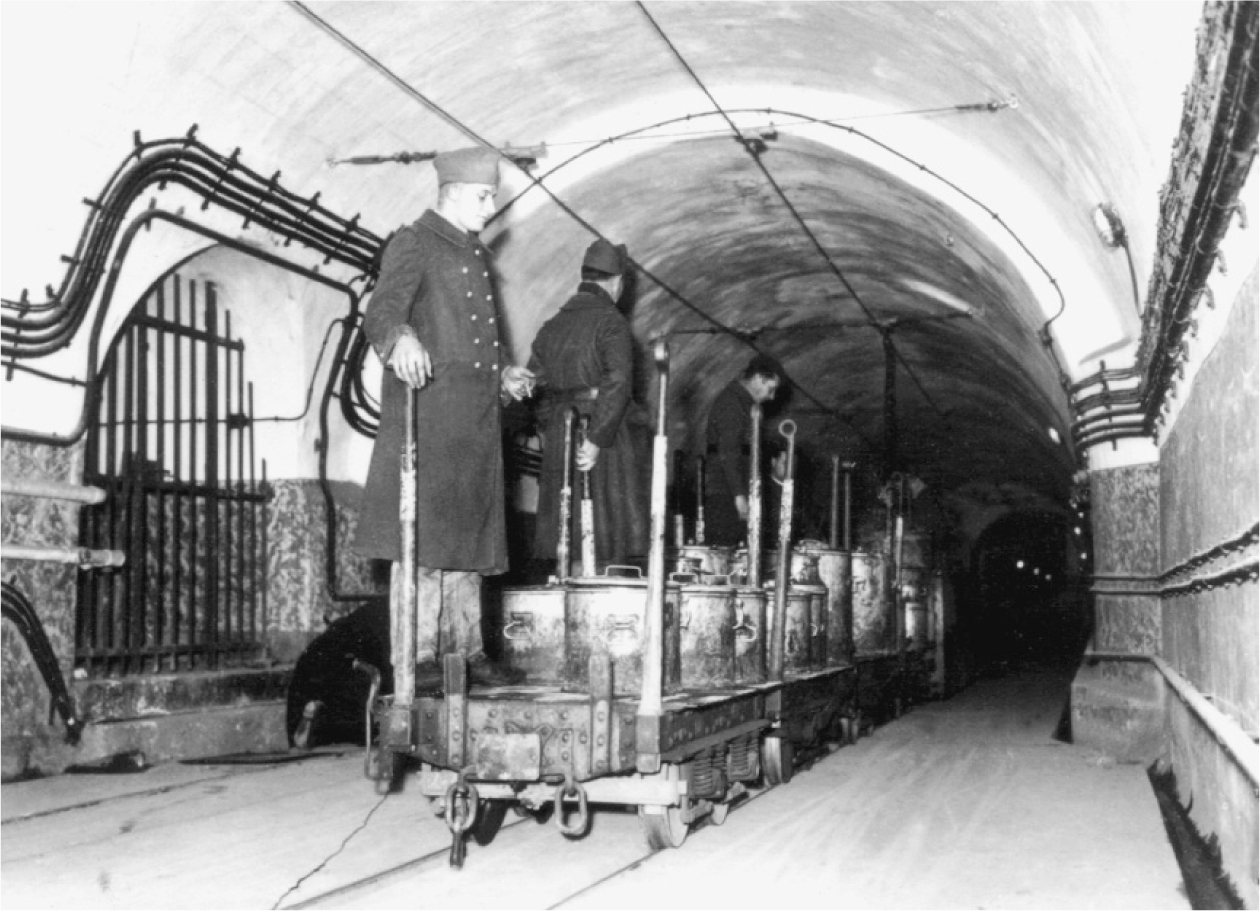

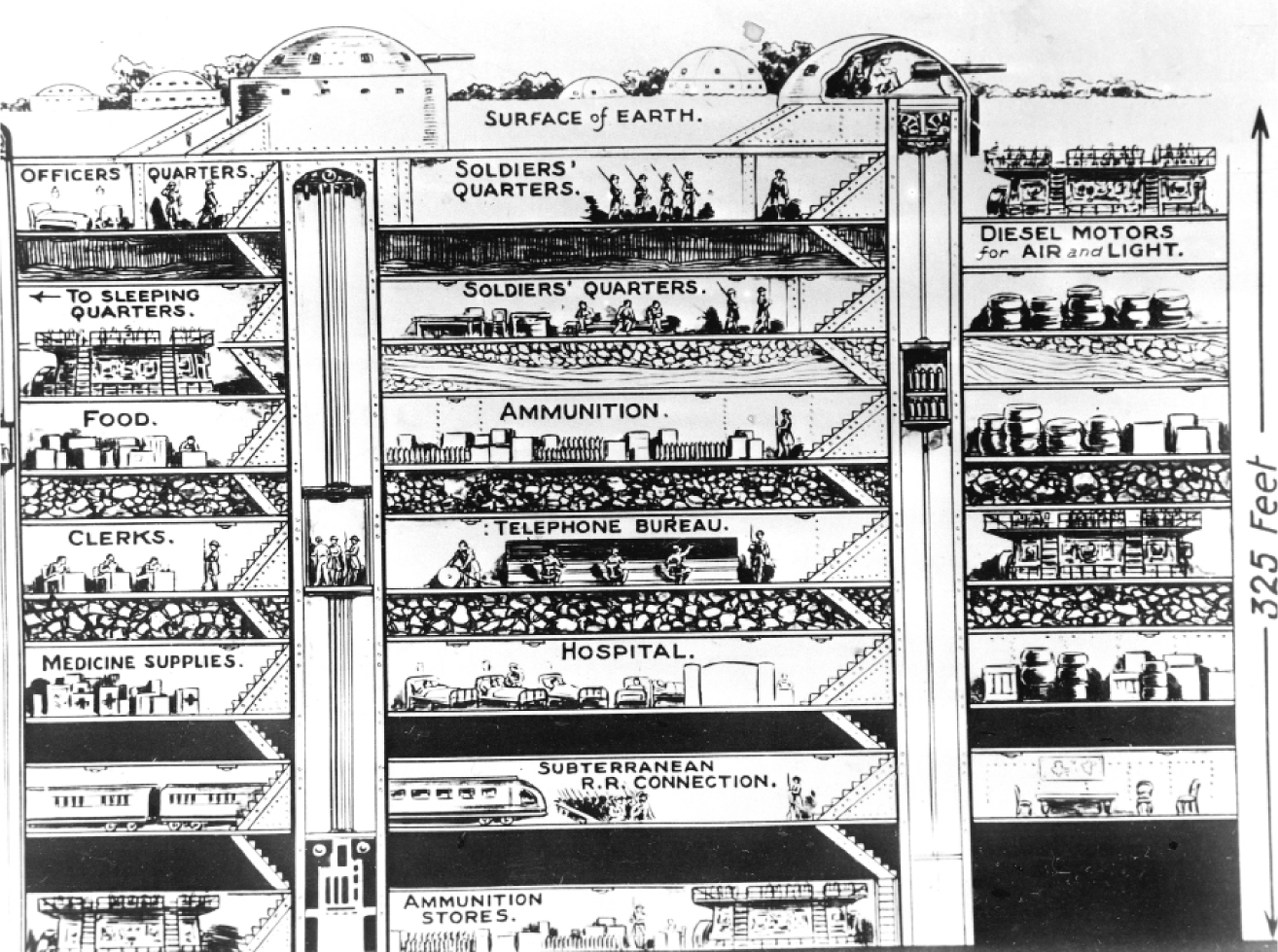

Even as a boy of six, I observed that everybody in France talked about la ligne Maginot reverentially as if it were a holy object, some older ladies even making a discreet sign of the cross when it was mentioned. It was explained to me that it was a line of underground fortresses designed to protect France from invasion, which I already knew because far from being secret, the Maginot Line, which had cost France over three billion francs to build and stretched almost five hundred miles from the Swiss border to Luxembourg, was widely publicized. Lavish photo displays of it had appeared in such magazines as Life in the United States, Picture Post and the Illustrated London News in the United Kingdom, and the equivalents all over the world. For a child who liked to play with toy soldiers and castles, there was something irresistibly fascinating about underground fortresses connected by electric railway lines buried deep in the earth, and armored steel turrets that rose from apparently peaceful meadows and hills like gigantic mushrooms at the push of a button.

My father even had big enlargements of photographs of the Maginot Line stacked in the clutter of his studio at home—he had based some of his designs on them for Things to Come, Alex’s film of the futuristic H. G. Wells novel—and they were very impressive, with guns of every size raised and lowered by gleaming pneumatic tubes and aimed by telescopic periscopes, like that in a submarine. The silent underground electric trains, the ammunition hoists, the water filtration plants and the state-of-the-art air-conditioning, the network of telephone lines linking every part of it together—it was all decades ahead of its time, a modernist triumph equal in its own way to the German autobahns.

The more publicity the Maginot Line received, the happier the French were—they even ran tours of it, and those who took the tour were given a small stamped silver medal, as if they had visited a shrine like Lourdes—for its purpose, after all, was to deter invasion. The whole object of all this concrete, steel, and technology was to prevent a war, not to win one. Left unsaid was the fact that the shape of the French frontier with Germany created what amounted to “a salient,” with its base stretching from Metz to Strasbourg and its tip pointing toward Karlsruhe, of exactly the kind that had cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of men in the Great War but on a much larger scale, and the more important reality that the line of interconnected forts, pillboxes, and antitank ditches ended south of the Belgian frontier.

An underground electric train delivers the soup, Maginot Line, 1939.

The French did not want to seal themselves off from neutral Belgium, even though attacking France through Belgium had been the heart and soul of the famous Schlieffen Plan in 1914, which very nearly succeeded. More dangerous still, the Maginot Line did not protect the Ardennes Forest, which, for reasons of economy and disputes between rival French strategists, was left undefended on the grounds that it could not easily be crossed by a modern, mobile army because of the rough terrain, dense woods, narrow secondary roads, steep valleys, and numerous rivers and streams that cut through it. Marshal Pétain himself had said so, and who would argue with the man who had held Verdun in the most costly battle of the Great War?

Cross-section of a Maginot Line fort.

Considering that the Ardennes Forest had originally been named by the Romans, who had fought many battles there against the German tribes, and that it has been fought over ever since then in every century, this proved to be an illusion, and the French, of all people, should have known better. If the Romans could hack their way through the Ardennes nearly two millennia earlier, so presumably could the Germans, but such fears were pooh-poohed by the French general staff, and the British, whose initial contribution to the defense of France would only consist of two infantry divisions, were in no position to dispute it, even had they cared to. What concerned the British more was that they could not move forward to take up defensive positions in Belgium until or unless the Germans breached Belgium’s neutrality.

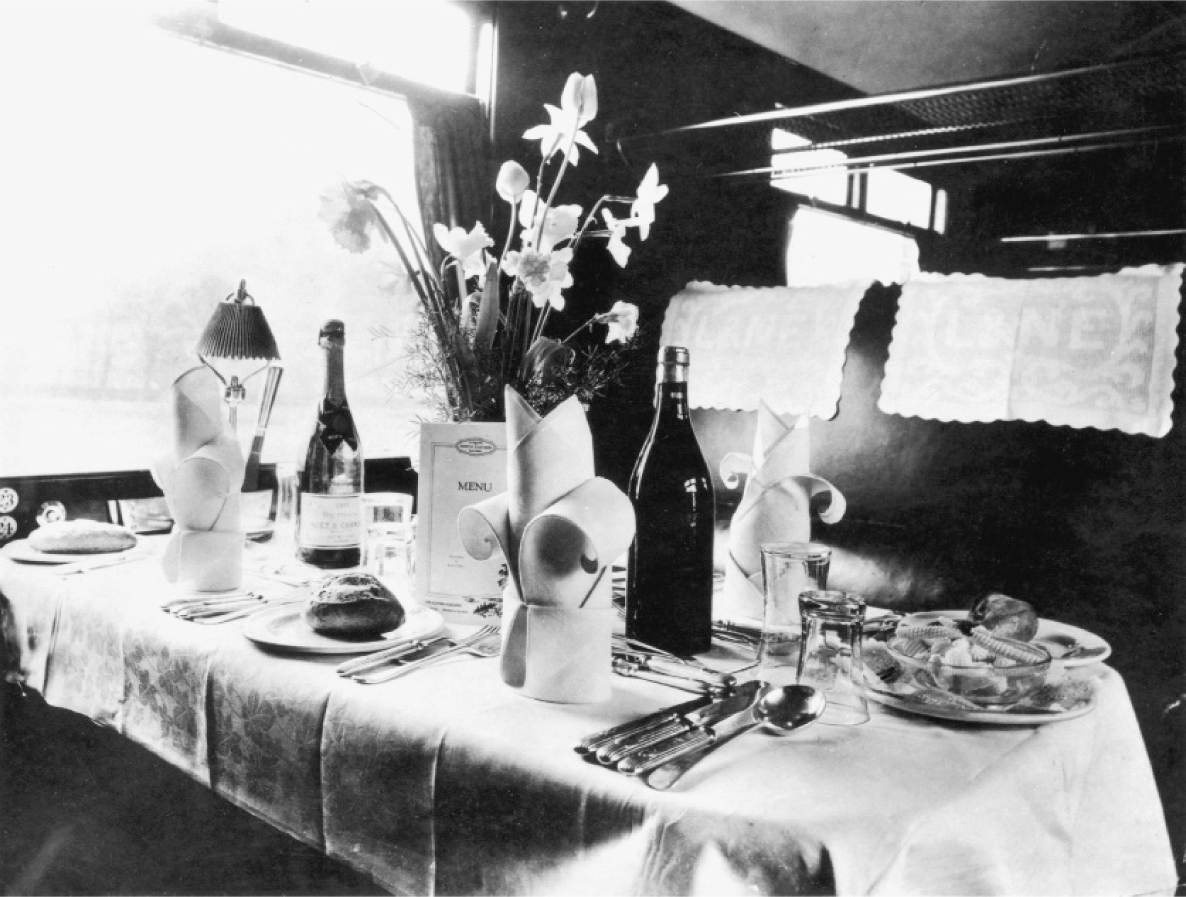

Vincent’s sense of urgency was relative, and by the time we boarded the Blue Train at Cannes with our mountain of luggage it was the last week of August, and events were already moving more swiftly than he knew. The Blue Train in those days was still one of the great trains de luxe of Europe, the sleeping compartments elegantly furnished, the food and the service impeccable. My father and mother had one compartment, Nanny Low and I the adjoining one, with a connecting door between them. Even to this day I can recall with pleasure the sheer perfection of the sheets once the beds had been lowered and made up, the linen of a smoothness that could only be found traveling first class on wagons-lits and ocean liners. The train was full, mostly of wealthy British people who like us were trying to get home in case the crisis turned into a war. There was no sense of panic, merely a certain guilt at having waited to the last moment to leave the south of France, and a degree of camaraderie that strangers—particularly well-dressed British strangers of a certain class—don’t typically exhibit. The train was longer than usual—third-class carriages had been added to it, and as it made its stops at Marseille and Lyon during the night, they filled up with men wearing the khaki uniform of the French Army.

First-class dining car, 1939.

At every station we passed there were more of them, waiting for trains that would take them to the depot of their regiment. From time to time they wandered through the sleeping cars and restaurant car, no doubt out of curiosity to see how the rich traveled, many of them smoking a pungent, unmistakably French cigarette, a Gauloise or a Gitane. The soldiers seemed resigned and glum rather than enthusiastic, and did not present the spit-and-polish appearance, social deference, and disciplined behavior of British regulars—their long, baggy overcoats were unbuttoned, most of them had left the collar of their tunic unfastened, their boots and brass were dull, and some were poorly shaved. Every so often one of the wagon-lit porters would shoo them back to their carriages, and they left with undisguised resentment. It was not just class resentment but also a hint of strong French resentment toward their ally.

The French felt—many, perhaps most—that they had been dragged by Britain, still as always in French minds l’Albion perfide, first into the Czech crisis and now the Polish crisis, and that if war came they would be left to fight it while the British sheltered behind their fleet and took their own sweet time to arrive on the battlefield in any significant number. The French Army, once fully mobilized, would consist of 86 divisions in France alone, over three and a half million men, one of the largest in the world (the German Army consisted of 116 divisions). By contrast, the British had only two regular divisions to send to France on the outbreak of war, to be reinforced by two more divisions about a month thereafter, and then formed into two corps, a formidably professional army, but tiny by Continental standards.

Anti-British posters, France, 1939. “Dead for Whom? For England!”

The French reminded themselves constantly that they had no other significant ally—pushed by the British they had consented to the loss of Czechoslovakia and turned away from an alliance with Soviet Russia. The United States was three thousand miles away, still recovering from the Great Depression, lost in the fog of isolationism and determined not to be dragged into another war in Europe, Poland was neither a democracy nor in any position to help France, while Italy was frankly hostile—Mussolini made no secret of his desire to annex French territory—and therefore successive French governments between the wars were obliged to do their best to please the British.

There were plenty of linguists in the British regular Army, and in the days of the empire no shortage of officers who spoke Urdu, Pashtu, Hindustani, Arabic, or Swahili, but in the 1914–1918 war young Captain Edward Spears had been made liaison officer to the French high command because of his rare gift of fluent French, and in World War Two he would be recalled at a much higher rank** to the same duty, so rare was it for a British officer to speak flawless French—indeed so uncommon that in France it was generally believed by the French generals that Spears must be Jewish.

In those days being on a train de luxe was like being cut off for a time from all news. My father and my mother ate a long and elaborate meal in the dining car—the food on the great trains was at the level of at least a one-star restaurant, with superb service and a long wine list—while Nanny Low and I were served dinner in our compartment before the attendant made up our beds for the night.

The next day the train shunted around the dreary outskirts of Paris, shedding the extra carriages and the soldiers for the next stage of the journey to Calais and the cross-Channel ferry. I remember my mother’s pointing out to me the bold red posters that were already being put up on walls of the Gare Maritime at Calais showing a map of the French empire with the slogan “Nous vaincrons parce que nous sommes les plus forts,” (We shall win because we are the strongest), but otherwise I remember very little of that day, which seemed endless to a child of six—meals, the coming and going of officials, inexplicable delays, then at last the appearance of British customs officers and the overwhelming presence of England surrounding us, the sea air, so much saltier, cooler, and moister than that of the Mediterranean, the slightly brackish smell of tidal waters at Dover, and the comforting sound of English being spoken all around us. The waiters and porters were English now, and familiar things were available: tea, of course, Marmite, Colman’s mustard, toast in a silver toast rack covered with a cozy to keep it warm, English butter that for some reason was never as nice as French butter. Outside the train newspaper vendors had their signs put up, one of them with the simple, scrawled headline in big, black letters: “WAR?”

Nanny said as she sighed with relief, “It’s so nice to be home.”

_________________________

* The emperor Franz Joseph was emperor of Austria and king of Hungary, so all national institutions, including himself, were “kaiserlich und königlich,” that is, “imperial and royal.”

† For his part, the Führer was bored and annoyed by Chamberlain’s attempts to break the ice between them with small talk on the subject of dry-fly fishing, something about which Hitler knew nothing and cared less, and which led him to dismiss Chamberlain and his advisers as “worms.” This had unfortunate consequences in August 1939—Hitler believed that Chamberlain would not intervene if he attacked Poland, and he turned out to be wrong. Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax did worse, however—at his first meeting with Hitler he almost handed the Führer his overcoat and hat under the impression that he was a footman.

‡ Neville Chamberlain’s older half brother, Austen, was the more glamorous of the two; he became a respected foreign secretary and a Knight of the Garter who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1925.

§ It should be explained that the word “radical” in French politics does not connote, as it does in the UK and the US, wild-eyed, bomb-throwing anarchists, but describes instead members of the well-respected Radical Party, essentially bourgeois, republican, anticlerical defenders of the status quo. Daladier was suspect to small businessmen like M. Vial because he had favored the forty-hour week and other mild social reforms.

¶ I did not learn it until 1961, when my uncle Zoltan died, having asked for a rabbi to attend his funeral. My mother went to her grave at the age of ninety-four still convinced that this was another of my father’s practical jokes.

# The head of MI6 (or SIS, as it is also called) is always known as “C,” after the last name of its first director. Ian Fleming changed it to “M” for his Bond novels.

** He rose to become Major-General Sir Edward Spears, KBE, MC, CB, and to win the grudging praise of Charles de Gaulle.